Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thinking Analysis Paper

Uploaded by

api-245623958Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Thinking Analysis Paper

Uploaded by

api-245623958Copyright:

Available Formats

Running Head: THINKING ANALYSIS 1

Thinking Analysis

Cassie McLemore

Teachers College of San Joaquin

THINKING ANALYSIS 2

Thinking Analysis

In teaching and observing three lessons at three different grade levels I was able to look

at different students landscape of learning solely as an observer and as a participant in the

teaching process. At each grade level students were engaged and wanted to find the answers to

questions posed to them. What was surprising to me was the apprehension that students

displayed when asked to discuss with one another how to solve the problem. Most students

currently do not have the schema required to discuss their mathematical thinking. It seems that

this generation of kids is focused primarily on answering the question with a number. Therefore

mathematical instruction needs to begin including less repetitive questioning and more

discussion about how to solve problems. According to Storeygard, Hamm and Fosnot (2010) the

key to getting students to open up about what they know requires that Teachers . . . find

students strengths to build their self-confidence (p. 46). Students must be confident in their

ability or they will never be able to explain their thinking, because they truly do not understand

the processes needed for transferable skills. In each grade level I encountered this issue with

discussion and just wanting to give a numbered answer.

In the first grade lesson I asked two students (Miller and Noah) to share with me

everything they knew about 15. I wanted them to talk about what the number represented and

how they could numerically and graphically represent the number 15. Students began by telling

me purely the numbers involved in making 15 (5 and 1). Storeygard, et al., (2010) caution

teachers to listen carefully and make adjustments based on individual responses (p. 46). After

waiting several seconds for the students to elaborate or discuss the number 15, I prodded them

with other questions to inspire conversation, but conversation never came.

THINKING ANALYSIS 3

Most of the lesson continued this way with me guiding the students into answers, until

the light bulb went off and a pattern emerged. This was the breaking point. Where the

conversation began. Where, as Storeygard, et al., (2010) put it the child had enough self-

confidence to demonstrate his thinking in many ways (p.49). The child was excited and wanted

to run and tell his teacher how he figured out the pattern. It was amazing to watch and made me

realize that this is what learning is about finding that place where students are excited to build on

their learning. In teaching this lesson again I would remind myself that understanding a students

landscape of learning is something that requires time, good listening skills and differentiated

activities.

Looking at seventh grade students, who are developmentally much older than the first

graders, I was surprised to see some of the same struggles with explaining their thinking and

analyzing a problem for solution strategies. I did not teach this lesson, but was an active

observer. I did not focus on one child or group of children to study, but looked at the whole class

interaction and pieces of conversations I overheard while circulating. While observing this

lesson I noticed that the majority of students willing to speak or discuss were a select few. Most

students did not volunteer and the teacher did not use random calling on students. There were

several pockets of students off task just waiting for answers to be given so they could write them

down. After the lesson was delivered and independent practice started, I focused on one group

of students that were unclear about the estimation and how it worked.

Students in general are not fond of estimation and struggle with the concept. In the group

where I listed in there was disagreement as to how to tackle the problem. Most students just

wanted to divide the numbers as they were written. I interjected in some instances asking them

how they were going to round to find whole number answers and it took some specific detailed

THINKING ANALYSIS 4

questioning to get them on the right track. Storeygard, et al., (2010) would agree that

adjustments for the individual are necessary for equity to occur (p. 46). If I were teaching this

lesson I would have used the independent practice time to check in with groups of students that I

know struggle in mathematics. This would have allowed me to determine whether their current

landscape of learning allowed them to be successful with this new concept or if additional

differentiation was required.

In the eighth grade lesson that I taught a similar struggle with discussion occurred.

Students were presented with a word problem that required several steps for completion. I

presented the problem to the students and asked them to discuss how they would go about

solving it. Part of the issue that I had was that I had two students that were drastically diverse in

their knowledge of mathematics (one was an advanced algebra student and the other was a

remedial 8

th

grade math student). Initially the advanced math student wanted to jump right to an

equation that solved the problem without discussing how or why this would work (the equation

she initially proposed was actually incorrect). I interjected and asked how she knew this was

true and could she explain why she was doing this to the remedial math student.

In teaching this lesson again I would not mix two students that are so far apart

mathematically. The remedial student was apprehensive after the advanced student jumped

quickly to an equation. Storeygard, et al., (2010) warned that having diverse student pairs is

essential, but if those pairing are not optimal (where both students are contributing) then we are

just reinforcing the learned helplessness of the student struggling to understand (p. 55). I

also would have not talked so much about what they needed to find. One of my most difficult

character/teacher flaws is the need to help students understand and let them struggle with the

THINKING ANALYSIS 5

problem. This is what I will begin working on as I move forward in furthering my math

instruction.

THINKING ANALYSIS 6

Reference List

Storeygard, J., Hamm, J. & Fosnot, C., (2010). Determining what children know: Dynamic

versus static assessment. In Fosnot, C.T. (Eds.), Models of intervention:

Reweaving the tapestry (pp. 45 -70). New York, NY: National Council of

Teachers of Mathematics.

You might also like

- Mclemore Proposal Final MiaaDocument3 pagesMclemore Proposal Final Miaaapi-245623958No ratings yet

- ReflectionlessonstudyDocument5 pagesReflectionlessonstudyapi-245623958No ratings yet

- Miaa360 Lesson Study 7th GradeDocument5 pagesMiaa360 Lesson Study 7th Gradeapi-245618218No ratings yet

- Lesson Study 2nd GradeDocument6 pagesLesson Study 2nd Gradeapi-245618331No ratings yet

- Miaa360 Curriculum AnalysisDocument5 pagesMiaa360 Curriculum Analysisapi-245623958No ratings yet

- Miaa 350 Final ReflectionsDocument8 pagesMiaa 350 Final Reflectionsapi-245623958No ratings yet

- PD Plan Miaa 360Document5 pagesPD Plan Miaa 360api-245618331No ratings yet

- Lesson Study 8th GradeDocument5 pagesLesson Study 8th Gradeapi-245618331No ratings yet

- Miaa320 AudiorecordinglessonDocument4 pagesMiaa320 Audiorecordinglessonapi-245623958No ratings yet

- Miaa 330 FinalreflectionDocument4 pagesMiaa 330 Finalreflectionapi-245623958No ratings yet

- Intervention Unit Integers Mia 360Document22 pagesIntervention Unit Integers Mia 360api-245623958No ratings yet

- Miaa 320 FinalreflectionDocument3 pagesMiaa 320 Finalreflectionapi-245623958No ratings yet

- PBL Overview 1Document7 pagesPBL Overview 1api-245618331No ratings yet

- PBL 2Document6 pagesPBL 2api-245618331No ratings yet

- Miaa 340 DifferentiatedlessonandbibDocument13 pagesMiaa 340 Differentiatedlessonandbibapi-245623958No ratings yet

- Miaa 320 ArticleDocument1 pageMiaa 320 Articleapi-245623958No ratings yet

- Miaa 330 FinalprojectDocument16 pagesMiaa 330 Finalprojectapi-245623958No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Prac Res Q2 Module 1Document14 pagesPrac Res Q2 Module 1oea aoueoNo ratings yet

- Kate Elizabeth Bokan-Smith ThesisDocument262 pagesKate Elizabeth Bokan-Smith ThesisOlyaGumenNo ratings yet

- Precision Machine Components: NSK Linear Guides Ball Screws MonocarriersDocument564 pagesPrecision Machine Components: NSK Linear Guides Ball Screws MonocarriersDorian Cristian VatavuNo ratings yet

- Masteringphys 14Document20 pagesMasteringphys 14CarlosGomez0% (3)

- 4 Factor DoeDocument5 pages4 Factor Doeapi-516384896No ratings yet

- What Is A Problem?: Method + Answer SolutionDocument17 pagesWhat Is A Problem?: Method + Answer SolutionShailaMae VillegasNo ratings yet

- Evaluative Research DesignDocument17 pagesEvaluative Research DesignMary Grace BroquezaNo ratings yet

- Business Case PresentationDocument27 pagesBusiness Case Presentationapi-253435256No ratings yet

- EA Linear RegressionDocument3 pagesEA Linear RegressionJosh RamosNo ratings yet

- Paradigms of ManagementDocument2 pagesParadigms of ManagementLaura TicoiuNo ratings yet

- USDA Guide To CanningDocument7 pagesUSDA Guide To CanningWindage and Elevation0% (1)

- Emergency Management of AnaphylaxisDocument1 pageEmergency Management of AnaphylaxisEugene SandhuNo ratings yet

- THE DOSE, Issue 1 (Tokyo)Document142 pagesTHE DOSE, Issue 1 (Tokyo)Damage85% (20)

- Condition Based Monitoring System Using IoTDocument5 pagesCondition Based Monitoring System Using IoTKaranMuvvalaRaoNo ratings yet

- Case Study IndieDocument6 pagesCase Study IndieDaniel YohannesNo ratings yet

- Legends and Lairs - Elemental Lore PDFDocument66 pagesLegends and Lairs - Elemental Lore PDFAlexis LoboNo ratings yet

- Level 10 Halfling For DCCDocument1 pageLevel 10 Halfling For DCCQunariNo ratings yet

- ALXSignature0230 0178aDocument3 pagesALXSignature0230 0178aAlex MocanuNo ratings yet

- Open Far CasesDocument8 pagesOpen Far CasesGDoony8553No ratings yet

- The Dominant Regime Method - Hinloopen and Nijkamp PDFDocument20 pagesThe Dominant Regime Method - Hinloopen and Nijkamp PDFLuiz Felipe GuaycuruNo ratings yet

- IELTS Speaking Q&ADocument17 pagesIELTS Speaking Q&ABDApp Star100% (1)

- Test Bank For Fundamental Financial Accounting Concepts 10th by EdmondsDocument18 pagesTest Bank For Fundamental Financial Accounting Concepts 10th by Edmondsooezoapunitory.xkgyo4100% (47)

- LSMW With Rfbibl00Document14 pagesLSMW With Rfbibl00abbasx0% (1)

- Command List-6Document3 pagesCommand List-6Carlos ArbelaezNo ratings yet

- N4 Electrotechnics August 2021 MemorandumDocument8 pagesN4 Electrotechnics August 2021 MemorandumPetro Susan BarnardNo ratings yet

- SBI Sample PaperDocument283 pagesSBI Sample Paperbeintouch1430% (1)

- Human Rights Alert: Corrective Actions in Re: Litigation Involving Financial InstitutionsDocument3 pagesHuman Rights Alert: Corrective Actions in Re: Litigation Involving Financial InstitutionsHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet

- Easa Management System Assessment ToolDocument40 pagesEasa Management System Assessment ToolAdam Tudor-danielNo ratings yet

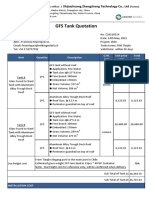

- GFS Tank Quotation C20210514Document4 pagesGFS Tank Quotation C20210514Francisco ManriquezNo ratings yet

- United-nations-Organization-uno Solved MCQs (Set-4)Document8 pagesUnited-nations-Organization-uno Solved MCQs (Set-4)SãñÂt SûRÿá MishraNo ratings yet