Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Africanamericanyouthprisonsystem

Uploaded by

api-288011515Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Africanamericanyouthprisonsystem

Uploaded by

api-288011515Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

Nick Banta

African American Youths: How and Why Do They End Up In the Prison

System?

Portland State University

The Unsettling Truth

It is a matter of fact that children are our future, as we are the children of our past. The

progression of our society relies on their bright minds and brilliant ideas. Along with the melding

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

2

of ideas, comes the same melding of cultures that make up the United States. The United States

is one of the most racially diverse countries on the planet. While all of this information seems

hopeful, it all comes crashing down due to a heartbreaking fact: African American children face

harsh discrimination as early as preschool, and that discrimination could very likely carry them

to prison later in life.

I started writing this essay under the premise that our criminal justice system was solely

to blame in setting-up African American youths for failure. With recent events in the news media

involving law enforcement officials making poor, racially biased judgement calls, this seemed to

be the truth. A classmate of mine had chosen to discuss the school-to-prison pipeline, which I

thought was an oddly specific topic to discuss. Unfortunately, as I started conducting my

research, I found out I was dead wrong.

Article after article, every one I read, talked about how schools were the culprit. Not only

is there a direct correlation between discrimination in the school and prison systems, but

discrimination in the school system is, in most cases, directly responsible for African American

youths ending up in the prison system. The disgusting fact behind all of this is that its not an

end-of-high-school, welcome to the real world scenario. The discrimination can begin as early

as preschool.

Preschool is when most children are just learning social interaction. They havent yet

begun to learn simple mathematics, nor have they necessarily begun reading and writing. They

are still learning to communicate, and still cling to their childhood innocence. Now, take those

children out of the classroom, and put them in front of a jury. Not a just, unbiased jury, but a jury

that is there to make sure that any hope they have for a positive future is rapidly extinguished.

This is what has been done to African American youth.

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

3

How It All Begins

In schools, African Americans have the highest rates of detention, suspensions,

expulsions, and special education placements. (Harvey & Hill, 2004). Placement in special

education programs happens more often among African American children than it does among

White children. This is partially due to the fact that their families incomes dont support

additional education outside of public schools. Now, you may be thinking, I didnt partake in

additional education, and I never wound up in special education programs, but its often due to

the fact that American education is geared towards White American children. Psychological

research has proven that people accel at tests when the material covered is relatable. While

African American history and culture are taught frequently around Martin Luther King Jr.s

birthday, the relation between African American children and their education falls short the rest

of the year.

Another issue that may be taking place is that African American children are often

removed from their families. In child welfare they are most likely to be removed from their

parents, have their parents' rights terminated, and exit without being adopted or reunited with

their parents. (Harvey & Hill, 2004). When these children are removed from their families and

placed in foster care, they can feel outcast amongst their peers. This can lead to a disinterest in

their education which in turn can cause a drop in grades. The drop in grades then flags them for

placement into special education.

When children are placed in special education programs, they often develop a sense of

inequality and separation from their peers. This sense of inequality can cause children to act out

and become rebellious. Visible presentations of proper behaviors become expressions of

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

4

favorable school styles. Students who deviate in visible ways from these norms are often

perceived to be deviant and hence are devalued by other students and teachers. (Sherwin &

Schmidt, 2003). Rebellious behavior leads to disciplinary action, and repeated disciplinary action

can cause them to feel even more outcast than they already feel in special education programs.

As African American children are targeted more and more by school officials, a lot of

them decide that, rather than try to cooperate with or even beat the system of oppression, it

would be easier to just drop out of school. When they drop out of school, they often leave their

foster homes to become homeless or recruited into a survival culture of crime and drugs. (Harvey

& Hill, 2004). Their involvement with drugs and criminal activities causes them to become the

target of the criminal justice system, which has already developed a reputation for its oppression

against minorities. In the 2000 census, approximately 16% of American youth identified

themselves as Black, and according to the 2006 Uniform Crime Reports, African American youth

accounted for 59% of arrests for murders, 51% of arrests for violent crimes, 31% of property

offenses, and 30% of arrests for drug use.

It is widely recognized that African-American youth are significantly overrepresented in

many juvenile justice systems relative to their population percentages. (Nicholson-Crotty,

Birchmeier, & Valentine, 2009). In juvenile justice, African American youth have the highest

rates of arrests, detention while awaiting trial, being tried as adults, being more severely

sentenced at all stages of the system, and being incarcerated in secure juvenile or adult

correctional facilities. (Harvey & Hill, 2004). Minority youth comprise over 60 percent of

children detained by juvenile justice systems across the United States. They are more than eight

times as likely as their white peers to be housed in juvenile detention facilities. (Martin,

McCarthy, Conger, Gibbons, Simons, Cutrona, & Brody, 2011)(Nicholson-Crotty, Birchmeier, &

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

5

Valentine, 2009). African American boys born in 1991 have a 29 percent chance of being

imprisoned over their lifetime, compared with only a 4 percent chance among White boys.

(Harvey & Hill, 2004). These children become repeatedly involved in the justice system. From

there, the cycle of the school-to-prison pipeline resets itself, and their children, as well as their

childrens children and so on, risk falling into the same oppressive trap that their parents did.

Where Things Are Headed

With the school-to-prison pipeline becoming more and more noticeable, people are

beginning to take action. Not only are there steps being put in place to keep African American

children out of special education programs, but there are also programs to help children who

have already fallen victim to this form of discrimination.

In one program set up by the MAAT Center for Human and Organizational Enhancement,

Inc. of Washington, DC, data was obtained from a three-year evaluation of a youth rites of

passage demonstration project using therapeutic interventions based on Africentric principles.

At-risk African American boys between ages 11.5 and 14.5 years with no history of substance

abuse were referred from the criminal Justice system, diversion programs, and local schools. The

evaluation revealed that participating youths exhibited gains in self-esteem and accurate

knowledge of the dangers of drug abuse. Although the differences were not statistically

significant, parents demonstrated improvements in parenting skills, racial identity, cultural

awareness, and community involvement. Evidence from interviews and focus groups suggests

that the program's holistic, family-oriented, Africentric, strengths-based approach and indigenous

staff contributed to its success. (Harvey & Hill, 2004).

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

6

This particular program helps African American youth develop emotional strength to

become advocates for themselves and their community using peer support, the Nguzo Saba (the

seven principles of Kwanzaa), and Africentric principles. It begins with an eight-week

preinitiation or orientation phase which concludes with a youth retreat and subsequent weekly

meetings emphasizing African and African American culture. The final phase of the program

consists of a transformational ceremony to serve as a rite of passage. During this ceremony, the

youths demonstrate their personal growth, knowledge, and skills to an audience made up of their

family members, staff members, and other significant people in their lives. (Harvey & Hill,

2004).

Another program that was put in place is know as the I Have A Future (IHAF) program.

This program, based out of Tennessee, focuses on career development in urban African American

youth. IHAF uses the same Africentric perspective found in the program set up by MAAT. Rather

than focusing on youths ages 11.5 to 14.5 years old, it focuses on youths ages 14 to 17. These are

the youths who are approaching adulthood and need to have a path set for them to ensure a

successful future. They used career development classes, counseling, and job preparation training

with Africentric focus, and again, the Nguzo Saba. Prominent community figures and

organizations such as elected officials, other human services agencies, church leaders, and

positive African American roles models were identified to collaborate in an attempt to educate

the youths. (Harvey & Hill, 2004).

Suggestions all point towards cultural intervention. African-centered rites of passage

provide cultural enlightening, as well as providing the youths with a sense of pride. Nsenga

Warfield-Coppock, a prominent figure in the study of rites of passage among African American

youths, conducted a survey of 20 rites of passage experts. Together, these experts had conducted

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

7

87 rites of passage programs between 1984 and 1992 involving 1,616 youths. Ninety percent of

the experts stated that knowledge of self and culture is crucial for youths confronting the

problems that they are faced with.

The Nguzo Saba , as cited earlier, has been an effective tool in the reformation of at-risk

African American youth. It holds not only onto the Africentric culture, but also provides a sort of

code of conduct for the youths. The Seven Principles, as they are known, read as follows:

Umoja (Unity): To strive for and maintain unity in the family,

community, nation, and race; Kujichajulia (Self-Determination): to

define ourselves, name ourselves, and speak for ourselves instead of

being defined and spoken for by others; Ujima (Collective Work and

Responsibility): to build and maintain our community together and to

make our brothers' and sisters' problems our problems and to solve

them together; Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics): to build and own

stores, shops, and other business, and to profit together from them; Nia

(Purpose): to make as our collective vocation the building and

developing of our community in order to restore our people to their

traditional greatness; Kuumba (Creativity): to do always as much as

we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more

beautiful and beneficial than when we inherited it; Imani (Faith): to

believe in our parents, our teachers, our leaders, our people, and

ourselves, and the righteousness and victory of our struggle.

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

8

As is evident, the Nguzo Saba lays out guidelines for these youths to follow to help not only

themselves, but others in their community. (Harvey & Hill, 2004).

How Things Have Changed

The programs discussed in this essay, coupled with assistance from social workers, have

had a huge impact on removing African American youths from the school-to-prison pipeline.

Social workers are working hand-in-hand with the criminal justice agencies to help troubled

youths establish productive lives. (Goodman, Getzel, & Ford, 1996).

With the rite of passage program set in place by MAAT, the youths involved acquired

much knowledge and positive values in the first eight weeks alone. Statistics showed increased

self-esteem and knowledge of the consequences of drug use, and better yet, the increase was

much higher than that of youths that didnt participate in the program. Self esteem rose from 40

percent to 81 percent in participants, whereas self-esteem rose to only 68 percent of comparison

youths. 83 percent of the youths in the program reported that it helped increase their self-esteem

very much. Accurate knowledge of the consequences of substance abuse increased from 60

percent to 85 percent. The program also enhanced their motivation for learning by promoting

their appreciation for reading, biology, science, and mathematics, as well as household skills.

The youths arent the only ones benefiting from these programs either. The parents and

guardians of the youths showed significant increases as well. Parenting skills increased 37

percent, community involvement increased 25 percent, and cultural awareness increased 36

percent. 80 percent of parents also reported that the bond with their child increased and 71

percent of their children felt the same way. (Harvey & Hill, 2004).

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

9

In closing, there is clearly a solution to the problem on the family side of the spectrum,

but the problem still remains unsolved on the administrative side. The youths have been provided

with effective ways of avoiding becoming targets. The school and criminal justice systems,

however have yet to remedy the fact that they are openly targeting and discriminating against

African American youths. With recent events involving African American youths and law

enforcement officials, change is definitely in order.

References

Goodman, H., Getzbel, G. S., & Ford, W. (1996). Group Work with High-Risk Urban Youths on

Probation. Social Work, 41(4), 375-381.

Harvey, A. R., & Hill, R. B. (2004). Africentric Youth and Family Rites of Passage Program:

Promoting Resilience among At-Risk African American Youths. Social Work, 49(1), 6574.

Martin, M. J., McCarthy, B., Conger, R. D., Gibbons, F. X., Simons, R. L., Cutrona, C. E., &

Brody, G. H. (2011). The Enduring Significance of Racism: Discrimination and

African American Youths: Ending Up in the Prison System

10

Delinquency Among Black American Youth. Journal Of Research On Adolescence

(Wiley-Blackwell), 21(3), 662-676.

Nicholson-Crotty, S., Birchmeier, Z., & Valentine, D. (2009). Exploring the Impact of School

Discipline on Racial Disproportion in the Juvenile Justice System. Social Science

Quarterly (Wiley-Blackwell), 90(4), 1003-1018.

Sherwin, G. H., & Schmidt, S. (2003). Communication Codes Among African American

Children and Youth - The Fast Track From Special Education to Prison?. Journal Of

Correctional Education, 54(2), 45.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- DLL - English 10 - Q3 - W1Document5 pagesDLL - English 10 - Q3 - W1CRox's Bry86% (7)

- RaceasociallymediatedideaDocument2 pagesRaceasociallymediatedideaapi-288011515No ratings yet

- MalcolmxpaperDocument5 pagesMalcolmxpaperapi-288011515No ratings yet

- ThereisonlyawhiteproblemDocument3 pagesThereisonlyawhiteproblemapi-288011515No ratings yet

- ArgumentativepaperDocument6 pagesArgumentativepaperapi-288011515No ratings yet

- KanstroominterviewDocument5 pagesKanstroominterviewapi-288011515No ratings yet

- Top Class Education Scheme 2018Document27 pagesTop Class Education Scheme 2018ambika anandNo ratings yet

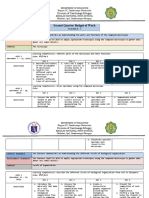

- Second Quarter Budget of Work Grade 7 - ScienceDocument6 pagesSecond Quarter Budget of Work Grade 7 - ScienceRONNEL GALVANONo ratings yet

- Mod.2 - Language Used in Academic Texts From Various DisciplinesDocument3 pagesMod.2 - Language Used in Academic Texts From Various DisciplinesHonelyn FernandezNo ratings yet

- Discussion Topic 1 - Understanding How Art Can Meet Some Human NeedsDocument1 pageDiscussion Topic 1 - Understanding How Art Can Meet Some Human NeedsGwendolyn EmnacenNo ratings yet

- Assignment - 02 - 8609Document10 pagesAssignment - 02 - 8609Tariq NaseerNo ratings yet

- 369778829-Resume-Lochlan-Scholefield 1Document2 pages369778829-Resume-Lochlan-Scholefield 1api-389409877No ratings yet

- Bryant Katie CVDocument3 pagesBryant Katie CVapi-517837731No ratings yet

- English Public Test Specifications (Emsat)Document14 pagesEnglish Public Test Specifications (Emsat)Hala LutfiNo ratings yet

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Act: Students' RightsDocument14 pagesIndividuals With Disabilities Education Act: Students' Rightsapi-551836854No ratings yet

- 2001teched1112 DraftdesignDocument130 pages2001teched1112 DraftdesignchristwlamNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Technologies For Education: Wadi D. Haddad Alexandra DraxlerDocument16 pagesThe Dynamics of Technologies For Education: Wadi D. Haddad Alexandra Draxlerjoko26No ratings yet

- Building A Future On A Foundation of Excellence: Division of Davao CityDocument2 pagesBuilding A Future On A Foundation of Excellence: Division of Davao CityMike ReyesNo ratings yet

- U.G. Merit Cutoff College Wise Subject Wise Gaya DistrictDocument16 pagesU.G. Merit Cutoff College Wise Subject Wise Gaya Districtanurag kumarNo ratings yet

- MGT 413 Organizational Training and Personal DevelopmentDocument6 pagesMGT 413 Organizational Training and Personal DevelopmentPrajay MathurNo ratings yet

- Talk2Me Video - : Before WatchingDocument1 pageTalk2Me Video - : Before WatchingRocio Chus PalavecinoNo ratings yet

- Parental Guidance is Key to SuccessDocument2 pagesParental Guidance is Key to SuccessCristy Amor TedlosNo ratings yet

- Educ587 - Streaming Video PresentationDocument29 pagesEduc587 - Streaming Video Presentationapi-548579070No ratings yet

- The Careers Handbook - The Ultimate Guide To Planning Your Future by DKDocument322 pagesThe Careers Handbook - The Ultimate Guide To Planning Your Future by DKDen Deyn Agatep100% (1)

- New Business SBA Guidelines..Document5 pagesNew Business SBA Guidelines..javiersimmonsNo ratings yet

- Cognitive and MetacognitiveDocument2 pagesCognitive and MetacognitiveJomel CastroNo ratings yet

- 500 Word Summary CombinedDocument11 pages500 Word Summary Combinedapi-281492552No ratings yet

- IB Research Skills Scope and Sequence - To Share - Sheet1Document3 pagesIB Research Skills Scope and Sequence - To Share - Sheet1Karen Gamboa MéndezNo ratings yet

- A Survey Research On The Satisfaction of The STEM Students To The School FaDocument37 pagesA Survey Research On The Satisfaction of The STEM Students To The School FaJohn Michael PascuaNo ratings yet

- WLL LS1English Q2W1M1L1 ATTENTIVELISTENINGDocument3 pagesWLL LS1English Q2W1M1L1 ATTENTIVELISTENINGAlhena ValloNo ratings yet

- Schools Division Pre-Test Item AnalysisDocument6 pagesSchools Division Pre-Test Item AnalysisHershey MonzonNo ratings yet

- The Gender Pay Gap: Income Inequality Over Life Course - A Multilevel AnalysisDocument14 pagesThe Gender Pay Gap: Income Inequality Over Life Course - A Multilevel AnalysisMango SlushieNo ratings yet

- Green Point Gazette 3-26-09Document2 pagesGreen Point Gazette 3-26-09jlipson304No ratings yet

- Institutional Vision and MissionDocument7 pagesInstitutional Vision and MissionJose JarlathNo ratings yet

- CV Writing (E2) LPDocument3 pagesCV Writing (E2) LPkadriye100% (1)