Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Daniel Hux Appeal

Uploaded by

Anonymous ovJgHACopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Daniel Hux Appeal

Uploaded by

Anonymous ovJgHACopyright:

Available Formats

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 1

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 15-10654

United States Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

FILED

April 22, 2016

Lyle W. Cayce

Clerk

DANIEL HUX,

PlaintiffAppellant,

versus

SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY,

a Texas Not-for-Profit Corporation;

RICHARD A. SHAFER, SMU Police Chief; LISA WEBB; STEVE LOGAN,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Texas

Before DAVIS, SMITH, and HIGGINSON, Circuit Judges.

JERRY E. SMITH, Circuit Judge:

Daniel Hux, a former student at Southern Methodist University

(SMU), appeals the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) dismissal of his

Texas tort claim for alleged breach of the duty of good faith and fair dealing.

Because Texas law does not impose a duty of good faith and fair dealing in the

student-university relationship, we affirm.

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 2

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

I.

Hux was an undergraduate student and community advisor (CA) 1 at

SMU during the 20102011 academic year. 2 His troubles began in 2011, when

he had a series of encounters with SMU staff members and an SMU student

that eventually resulted in his dismissal as a CA.

In January 2011, Stephanie Howeth (a full-time SMU staff member who

lived on campus and supervised some of the CAs) requested that Hux meet

with her in person to discuss student/staff relationships and clear up some

boundaries. During their meeting, Howeth explained that three interactions

with Hux had left her with the impression that he was making romantic overtures to her that had made her feel uncomfortable. Hux replied that Howeth

had misinterpreted his actions. Being careful not to hurt her feelings, Hux

carefully explained to Howeth that he had no interest in her whatsoever.

Hux apologized and thought the matter resolved. Howeth, though, had already

informed her supervisors of the conduct and the planned meeting.

The next day, Dorothea Mack (Howeths supervisor) requested that Hux

meet with her. At this meeting, Mack indicated that she was not recommending Hux for reappointment to his CA position the next year, because Howeth

was uncomfortable with Hux and . . . he was in denial about his very troubling

[] remarks to Howeth. Hux had several additional meetings, regarding his

conduct, with Mack and Macks supervisor, Adrienne Patmythes, the Assistant

Director for Training and Development in the SMU housing department, in

January and into February 2011. The meetings sometimes became heated. In

Community advisor appears to be SMUs local name for a resident advisora

student hired to supervise a dormitory.

1

Reviewing this Rule 12(b)(6) dismissal, we assume Huxs factual allegations are true.

Our recitation of the facts is drawn from Huxs complaint and the district courts construction

of the factual allegations in the complaint and the documents incorporated by reference.

2

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 3

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

addition to those tangles with the administration, Hux had a run-in with

another studenta fellow CAabout a trash problem[.] Administrators

accused Hux of speaking aggressively and inappropriately in the course of a

phone conversation with his colleague regarding the situation.

Things came to a head on February 10. Mack fired Hux from his CA

position, effectively immediately; Mack cited Huxs inappropriate behavior

and comments and referred to the incidents with Howeth and the trash incident with the other CA. Hux appealed his termination to Steve Logan, SMUs

Executive Director of Resident Life and Student Housing. Before his hearing

on the appeal, Hux met with Betty McHone, an Assistant Chaplain at SMU, to

go over the events that led to his termination. On February 18, Hux met in

person with Logan to discuss his appeal; also present were three SMU police

officers, including Chief Richard Shafer. The attendees discussed Huxs behavior and SMUs concerns. Shafer told Hux that he needed to visit with a doctor

to prove that he was not crazy. At the end of the meeting, Shafer escorted Hux

to SMUs mental health facility for an evaluation; Hux left, however, without

being evaluated.

Logan denied Huxs appeal by a letter dated February 21 that indicated

that Hux had made certain staff members fear for their safety. Though Hux

was allowed to remain enrolled as a student, he was prohibited from contacting

those involved in the incidents and was told to stay away from certain dormitories. In the course of the next week, Hux met with Dean of Student Life Lisa

Webb and Assistance Vice President of Student Affairs Troy Behrens; both

discussed Huxs behavior and asked what they could do to help. Hux also met

with unidentified persons from the Chaplains office during the next month.

On March 20, Hux attended a meeting for students interested in student

government positions. That meeting was held in a dormitory that Hux, under

3

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 4

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

the terms of the letter from Steve Logan terminating his CA employment, was

under orders to avoid. After the meeting, several SMU police officers approached Hux, told him there was a protective order prohibiting him from

being at the building, and searched Huxs person. One of Huxs relatives was

waiting in a car to pick him up; officers also searched the car and found a

handgun. The officers handcuffed Hux and put him into a police car. Twentyfive minutes later, they removed the handcuffs, returned the gun, and instructed Hux not to bring the gun to school or have it in his car. Hux left

campus.

The next day, two officers met Hux outside one of his classes and drove

him to the SMU police department. There, Shafer and Webb told him that he

was being placed on a mandatory administrative withdrawal from the university, citing his continued inappropriate behavior and attempts to intimidate

and threaten [housing department staff] members. Hux was given a letter

memorializing the conversation. After Hux was forced to withdraw from the

university, Shafer stated in an interview that Hux was no longer a student and

indicated that Hux had violated university policy. Further, SMU administrators circulated a picture of Hux coupled with a notice that community members

should be on the lookout for him.

II.

Hux sued, alleging about nineteen causes of action. The district court

granted the defendants Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss on most of the claims

and granted summary judgment for defendants on the rest of the claims after

discovery.

The only claim in issue on this appealthe notion that SMU

breached a duty of good faith and fair dealingwas among those dismissed

before discovery for failure to state a claim. Analyzing Texas law, the court

explained that Hux had not alleged facts that, taken as true, would give rise

4

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 5

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

to the type of special relationship that creates a duty of good faith and fair

dealing under Texas law. We agree and therefore affirm.

III.

We review a Rule 12(b)(6) dismissal de novo, accepting all well-pleaded

facts as true and viewing these facts in the light most favorable to the plaintiff. 3 Under Texas law, the question whether there is a tort duty of good faith

and fair dealing in a particular circumstance is initially a question of law. 4 The

court first must decide whether the plaintiff has alleged facts that, if taken as

true, would show that a special relationship even existed. Only when such a

relationship could in principle exist on the facts alleged does proof of the special

relationship become a question of fact.

IV.

In applying Texas law, we look first to the decisions of the Texas

Supreme Court. See Howe ex rel. Howe v. Scottsdale Ins. Co., 204 F.3d 624,

627 (5th Cir. 2000). If that court has not ruled on the issue, we make an Erie 5

guess, predicting what it would do if faced with the facts before us. Id.

Typi-

cally, we treat state intermediate courts decisions as the strongest indicator of

what a state supreme court would do, absent a compelling reason to believe

that the state supreme court would reject the lower courts reasoning. Id.

Texas law does not impose a generalized contractual duty of good faith

and fair dealing and, in fact, rejects it in almost all circumstances. See English

Toy v. Holder, 714 F.3d 881, 883 (5th Cir. 2013) (quoting Bustos v. Martini Club Inc.,

599 F.3d 458, 461 (5th Cir. 2010)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

3

See Crim Truck & Tractor Co. v. Navistar Intl Transp. Corp., 823 S.W.2d 591, 594

(Tex. 1992), superseded by statute on other grounds as noted in Subaru of Am., Inc. v. David

McDavid Nissan, Inc., 84 S.W.3d 212, 22526 (Tex. 2002); Cole v. Hall, 864 S.W.2d 563, 568

(Tex. App.Dallas 1993, writ dismd w.o.j.).

4

Erie R.R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938).

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 6

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

v. Fischer, 660 S.W.2d 521, 522 (Tex. 1983). But in an extremely narrow class

of cases, the Texas courts have determined that a special relationship may give

rise to a tort duty of good faith and fair dealing. See Arnold v. Natl Cty. Mut.

Fire Ins. Co., 725 S.W.2d 165, 167 (Tex. 1987).

A duty of good faith and fair dealing may arise in two contexts. The first,

not pertinent here, is when the parties are in a formal fiduciary relationship

(e.g., principal-agent, attorney-client, or trustee-beneficiary); in such situations, the ordinary bundle of duties incumbent on a fiduciary includes a duty

of good faith and fair dealing. See Crim Truck, 823 S.W.2d at 59394 (Tex.

1992). The second context, relevant here, is when the parties are not formal

fiduciaries but are nonetheless in a special or confidential relationship. Id. If

they are, Texas law imposes a duty of good faith and fair dealing (but not the

whole bundle of associated fiduciary duties). Id. at 594.

Texas courts usually describe this special relationship in broad terms.

The duty arises in discrete, special relationships, earmarked by specific characteristics including: long standing relations, an imbalance of bargaining

power, and significant trust and confidence shared by the parties. Caton v.

Leach Corp., 896 F.2d 939, 948 (5th Cir. 1990). The relationship must exist

before and apart from the contract or agreement that forms the basis of the

controversy. Transp. Ins. Co. v. Faircloth, 898 S.W.2d 269, 280 (Tex. 1995). A

partys unilateral, subjective sense of trust and confidence in the opposing

party is not sufficient to give rise to a special relationship and the attendant

duty. Schlumberger Tech. Corp. v. Swanson, 959 S.W.2d 171, 177 (Tex. 1997).

Because the Texas Supreme Court has not specifically addressed the specialrelationship doctrine in the student-university context, we turn to the decisions of the intermediate courts.

The Texas Courts of Appeals have restricted the special-relationship

6

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 7

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

doctrine to narrow and carefully circumscribed situations. Indeed, those courts

recognize only one special relationshipthat between an insurer and an

insured. 6 Texas courts have refused to impose a tort duty of good faith and fair

dealing on any of the following relationships: employer-employee, 7 lenderborrower, 8

medical

distributor, 11

provider-patient, 9

franchisor-franchisee, 12

mortgagor-mortgagee, 10

creditor-guarantor, 13

supplier-

issuer

and

beneficiary of a letter of credit, 14 or insurance company-third-party claimant. 15

An ordinary student-professor relationship is no different. The only

Texas court that appears to have considered the question found that there was

no special relationship there. See Ho v. Univ. of Tex. at Arlington, 984 S.W.2d

672, 693 (Tex. App.Amarillo 1998, pet. denied). Hux does not cite a single

See GTE Mobilnet of S. Texas Ltd. Pship v. Telecell Cellular, Inc., 955 S.W.2d 286,

295 (Tex. App.Houston [1st Dist.] 1997, writ denied) (Although often urged to do so, the

supreme court has hesitated to extend the duty of good faith and fair dealing to other contexts

beyond the special relationship between an insurance company and its insured. (quoting

Wheeler v. Yettie Kersting Meml Hosp., 866 S.W.2d 32, 52 (Tex. App.Houston [1st Dist.]

1993, no writ)); Georgetown Associates, Ltd. v. Home Fed. Sav. & Loan Assn, 795 S.W.2d 252,

255 (Tex. App.Houston [14th Dist.] 1990, writ dismd w.o.j.) (It is far from clear that the

so-called duty of good faith even exists. The supreme court has expressly disavowed the duty

as a general matter, with an exception for a special relationship between insurers and their

insureds.). The Texas courts recognized a second special relationshipin the tightly analogous case of a compensation carrier and a workers compensation claimantfrom 1988 until

2012, when the Texas Supreme Court reversed course. See Tex. Mut. Ins. Co. v. Ruttiger, 381

S.W.3d 430, 44749 (Tex. 2012) (overruling Aranda v. Ins. Co. of N. Am., 748 S.W.2d 210

(Tex. 1988)).

6

See Wheeler, 866 S.W.2d at 52 (collecting cases).

Id.

Id.

10

Id.

11

Id.

12

Id.

13

GTE Mobilnet, 955 S.W.2d at 295.

14

Id.

15

Id.

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 8

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

case in which a Texas court has extended the special-relationship doctrine to

any relationship save for that of an insured party and its insurer, and we are

not otherwise aware of any such decision. 16

V.

Hux points to three core allegations that, taken as true, would, in his

view, show the existence of a special relationship. First, he notes that SMU

officials encouraged him to obtain mental-health services and that Shafer

One Texas Supreme Court justices separate concurring opinion claimed that that

court has imposed a duty of good faith and fair dealing in a number of special relationships

outside of the insurance context. See English v. Fischer, 660 S.W.2d 521, 524 (Tex. 1983)

(Spears, J., concurring). That concurrence, however, does not correctly state current Texas

law or even Texas law in the past.

16

It is not accurate to say that the relationships that the opinion points topartnership,

agency, joint venture, and certain oil and gas relationshipsare examples of informal special

relationships giving rise to a quasi-fiduciary duty of good faith and fair dealing enforceable

in tort. Partners, joint venturers, and agents are all just ordinary formal fiduciaries. See

Fitz-Gerald v. Hull, 237 S.W.2d 256, 26465 (Tex. 1951) (stating that partners and joint venturers are fiduciaries); Davis-Lynch, Inc. v. Asgard Techs., LLC, 472 S.W.3d 50, 60 (Tex.

App.Houston [14th Dist.] 2015, no pet.) (stating that agents are fiduciaries).

This is not, therefore, evidence of a non-insurance special relationship. And, although

the holder of executive rights in a mineral property owes a duty of good faith and fair dealing

to holders of non-executive royalty interests in the estate, that duty is not grounded in the

special-relationship doctrine. The duty long predates the modern special-relationship doctrine (which is focused on insurance relationships). See Manges v. Guerra, 673 S.W.2d 180,

183 (Tex. 1984) (noting that the executive rights-holders duty stems from Schlittler v. Smith,

101 S.W.2d 543, 545 (Tex. 1937)). Some cases refer to the holder of executive rights as a

formal fiduciary. E.g., Luecke v. Wallace, 951 S.W.2d 267, 274 (Tex. App.Austin 1997, no

pet.). Others cite Justice Spearss concurrence and describe the duty in terms of the specialrelationship doctrine. E.g., Manges, 673 S.W.2d at 18384.

Recently, however, the Texas Supreme Court acknowledged the lack of clarity generated by the Manges decisions reliance on special-relationship-doctrine concepts and set

things on a clearer footing; the court concluded that an executive rights-holder owes an intermediate sort of duty that extends beyond ordinary good faith and fair dealing but does not

encompass the full bundle of duties incumbent on a formal fiduciary. See KCM Fin. LLC v.

Bradshaw, 457 S.W.3d 70, 7982 (Tex. 2015). The upshot is that the duty of good faith and

fair dealing in the oil-and-gas context is sui generis and has no bearing on the specialrelationship doctrine as elaborated in this opinion. Thus, Justice Spears concurring opinion

in English does not establish that the special-relationship doctrine has been used to impose

a duty of good faith and fair dealing on any non-insurance relationship.

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 9

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

escorted him to SMUs mental-health facility. Second, Hux notes that he met

with various individuals in the chaplains office on more than one occasion,

where he confided in numerous SMU personnel. Third, Hux points to his

meetings with Behrens and Webb, in which both administrators expressed a

desire to help him and evinced concern about his well-being. In sum, says Hux,

those facts demonstrate that SMU personnel encouraged him to confide in

them, to seek their guidance and direction, and to trust and rely on them.

Huxs appeal fails for at least two independent reasons. First, given the

Texas courts decades-long refusal to extend the special-relationship doctrine

beyond the insurance context, we are confident that the Texas Supreme Court

would hold that there is no duty of good faith and fair dealing in the studentuniversity relationship. No Texas court has ever extended the doctrine to that

relationship. And indeed, the closest case holds that there is nothing special

in an ordinary student-professor relationship in which a professor teaches,

supervises, advises, and evaluates a student. See Ho, 984 S.W.2d at 693. We

see no material distinction here.

Huxs allegations show nothing more than an ordinary studentadministrator relationship. Encouraging students to take advantage of university mental-health resources, counseling students, and offering help to students struggling through disciplinary problems are all workaday aspects of a

college administrators job. Allowing Huxs claim to go forward on the ground

that Texass highest civil court has not rejected his specific claim would run

afoul of our longstanding rule against front-running the state courts by adopting innovative theories of state law. See Rubinstein v. Collins, 20 F.3d 160,

172 (5th Cir. 1994).

Second, even assuming arguendo that the student-university relationship could possibly give rise to a duty of good faith and fair dealing, Huxs

9

Case: 15-10654

Document: 00513477596

Page: 10

Date Filed: 04/22/2016

No. 15-10654

allegations are not sufficient to show that such a relationship existed. None of

his theories demonstrate that his purported special relationship with SMU

administrators existed before and independently of the immediate circumstances of the course of events that led to his dismissal as a CA. The only facts

he points to occurred after the events giving rise to this suit were set in motion.

But a court may impose a duty of good faith and fair dealing only when the

special relationship predates and exists separately from the dispute at hand.

Faircloth, 898 S.W.2d at 280.

Also, Huxs claims demonstrate at most the sort of unilateral, purely subjective sense of trust that Texas courts have determined is insufficient to convert an ordinary arms-length relationship into a special or confidential relationship. See Swanson, 959 S.W.2d at 177. The mere fact that one party to a

transaction trusts the other or believes that the other has his interests at heart

does not create a special relationship. Crim Truck, 823 S.W.2d at 595. Huxs

allegations, even if true, show nothing more than his own unilateral trust and

belief in the administrators beneficence.

The judgment of dismissal is AFFIRMED.

10

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- AWS A5.2 Specification For Carbon and Low Alloy Steel Rods For Oxifuels Gas Welding (1992) PDFDocument21 pagesAWS A5.2 Specification For Carbon and Low Alloy Steel Rods For Oxifuels Gas Welding (1992) PDFJairo ContrerasNo ratings yet

- LABREL Digests Week 4 COMPLETEDocument62 pagesLABREL Digests Week 4 COMPLETEMetha DawnNo ratings yet

- A.L.a. Schecter Poultry Corp. v. United StatesDocument1 pageA.L.a. Schecter Poultry Corp. v. United StatesRejmali GoodNo ratings yet

- Confidentiality and Non-Circumvention Agreement ClausesDocument2 pagesConfidentiality and Non-Circumvention Agreement ClausesNick Ekonomides100% (1)

- Conducting Successful MeetingsDocument5 pagesConducting Successful MeetingsRhod Bernaldez EstaNo ratings yet

- Does Death Extinguish Civil Liability for CrimesDocument2 pagesDoes Death Extinguish Civil Liability for CrimesranaalyssagmailcomNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 125629, March 25, 1998: Sunga vs. TrinidadDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 125629, March 25, 1998: Sunga vs. TrinidadTinersNo ratings yet

- PD 1529. Sec 75,76,77Document8 pagesPD 1529. Sec 75,76,77Kai RaguindinNo ratings yet

- People V VersozaDocument2 pagesPeople V VersozaFriktNo ratings yet

- Carabeo Vs Dingco DigestDocument5 pagesCarabeo Vs Dingco DigestJoel G. AyonNo ratings yet

- Girl Scouts v. Boy Scouts ComplaintDocument50 pagesGirl Scouts v. Boy Scouts ComplaintDaniel BallardNo ratings yet

- Oliver Answer To Complaint PDFDocument22 pagesOliver Answer To Complaint PDFAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Dallas Science Fair Category ResultsDocument12 pagesDallas Science Fair Category ResultsAnonymous ovJgHA100% (1)

- Dallas Science Fair Special AwardsDocument7 pagesDallas Science Fair Special AwardsAnonymous ovJgHA100% (1)

- Suit Against BaylorDocument12 pagesSuit Against BaylorAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Fatality Review Five Year ReportDocument44 pagesFatality Review Five Year ReportAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Democrat MemoDocument10 pagesDemocrat MemoChuck Ross100% (2)

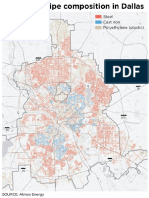

- What Types of Gas Pipes Run Under DallasDocument1 pageWhat Types of Gas Pipes Run Under DallasAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- What Types of Gas Pipes Run Under DallasDocument1 pageWhat Types of Gas Pipes Run Under DallasAnonymous ovJgHA100% (1)

- JJ Pearce HS Parent LetterDocument1 pageJJ Pearce HS Parent LetterAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- 2018 Dallas Science Fair ResultsDocument16 pages2018 Dallas Science Fair ResultsAnonymous ovJgHA67% (3)

- Fort Worth Police Department 2017 1st Quarter Crime ReportDocument30 pagesFort Worth Police Department 2017 1st Quarter Crime ReportAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- 2018 Dallas Science Fair Special AwardsDocument7 pages2018 Dallas Science Fair Special AwardsAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Letter To Commissioner Sid MillerDocument2 pagesLetter To Commissioner Sid MillerAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Plano Search WarrantsDocument4 pagesPlano Search WarrantsAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Young Americans For Freedom LetterDocument1 pageYoung Americans For Freedom LetterAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Baylor Ruling PDFDocument27 pagesBaylor Ruling PDFAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Oliver Answer To Complaint PDFDocument22 pagesOliver Answer To Complaint PDFAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Science Fair Special Awards (2017)Document7 pagesScience Fair Special Awards (2017)Anonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Baylor Ruling PDFDocument27 pagesBaylor Ruling PDFAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- UTA Sued by Former Student's FatherDocument52 pagesUTA Sued by Former Student's FatherAnonymous ovJgHA100% (1)

- Kirbyville CISD Release With Court BriefDocument13 pagesKirbyville CISD Release With Court BriefAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Letter From Former Dallas Police ChiefsDocument3 pagesLetter From Former Dallas Police ChiefsAnonymous ovJgHA100% (1)

- Science Fair Results (2017)Document11 pagesScience Fair Results (2017)Anonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Science Fair Results (2017)Document11 pagesScience Fair Results (2017)Anonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Science Fair Special Awards (2017)Document7 pagesScience Fair Special Awards (2017)Anonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Baylor Officials Respond To Colin Shillinglaw Libel SuitDocument54 pagesBaylor Officials Respond To Colin Shillinglaw Libel SuitAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Doe vs. Baylor UniversityDocument26 pagesElizabeth Doe vs. Baylor UniversityAnonymous ovJgHA100% (2)

- Important Message From Mayor Jess Herbst - New Hope, TXDocument2 pagesImportant Message From Mayor Jess Herbst - New Hope, TXAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- 1978 Deed RestrictionDocument5 pages1978 Deed RestrictionAnonymous ovJgHANo ratings yet

- Circuit Theory Fundamentals for Electrical EngineersDocument311 pagesCircuit Theory Fundamentals for Electrical EngineersArtur NowakNo ratings yet

- Datatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 129Document2 pagesDatatreasury Corporation v. Wells Fargo & Company Et Al - Document No. 129Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Registration of Corporations and Partnerships PDFDocument2 pagesRegistration of Corporations and Partnerships PDFJeremiash ForondaNo ratings yet

- Government Regulations and LabelingDocument9 pagesGovernment Regulations and Labelingapi-26494555No ratings yet

- Human & Civil RightsDocument16 pagesHuman & Civil RightsMohindro ChandroNo ratings yet

- Hans Dama - The Banat, A Penal ColonyDocument28 pagesHans Dama - The Banat, A Penal ColonyL GrigNo ratings yet

- 3 Repulic of The Philippines vs. CA 342 SCRA 189Document7 pages3 Repulic of The Philippines vs. CA 342 SCRA 189Francis LeoNo ratings yet

- 5th Wave Additional Case FulltextDocument23 pages5th Wave Additional Case FulltextMeku DigeNo ratings yet

- Williams v. Louisiana Supreme Court - Document No. 4Document2 pagesWilliams v. Louisiana Supreme Court - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- PDF of LLPDocument2 pagesPDF of LLPAiman FatimaNo ratings yet

- Participation Form For Freshmen Orientation 2023 17 May 23Document1 pageParticipation Form For Freshmen Orientation 2023 17 May 23Nguyễn Mã SinhNo ratings yet

- BIR Ruling No. 1279-18Document2 pagesBIR Ruling No. 1279-18kimNo ratings yet

- Asset:: Definition, Recognition, & Measurement IssuesDocument9 pagesAsset:: Definition, Recognition, & Measurement IssuescmaulanyNo ratings yet

- OSP Towing PolicyDocument4 pagesOSP Towing PolicyMNCOOhio50% (2)

- Service BulletinDocument14 pagesService BulletinVikrant RajputNo ratings yet

- Agreement Between A Manufacturer and Selling AgentDocument4 pagesAgreement Between A Manufacturer and Selling AgentVIRTUAL WORLDNo ratings yet

- MULTIPLEDocument7 pagesMULTIPLEKim EllaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Engineering Computation An Introduction Using Matlab and Excel 1st Edition Musto Solutions ManualDocument31 pagesFull Download Engineering Computation An Introduction Using Matlab and Excel 1st Edition Musto Solutions Manualaminamuckenfuss804uk100% (26)

- OFFLINE CLASS ACTIVITY FOR SPECIALIZED CRIME INVESTIGATIONDocument2 pagesOFFLINE CLASS ACTIVITY FOR SPECIALIZED CRIME INVESTIGATIONJohnwell LamsisNo ratings yet

- Ra 8560Document10 pagesRa 8560kimmey_09No ratings yet