Professional Documents

Culture Documents

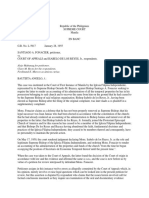

Civ Oblicon Digests

Uploaded by

CattleyaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Civ Oblicon Digests

Uploaded by

CattleyaCopyright:

Available Formats

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS determining culpability. The terms and conditions surrounding the 1.

GENERAL PROVISIONS ON OBLIGATIONS (ARTS. 1156-1162) issuance of the checks are also irrelevant. 1.4 SOURCES EMMA P. NUGUID V. CLARITA S. NICDAO G.R. No. 150785, September 15, 2006 FACTS: Accused Clarita S. Nicdao is charged with having committed 14 counts of Violation of BP 22. The criminal complaints allege that sometime in 1996, from April to August thereof, Nicdao and her husband of Vignette Superstore approached Nuguid and asked her if they could borrow money to settle some obligations. Having been convinced by them and because of the close relationship of respondent to petitioner, the latter lent the money. Thus, every month, she was persuaded to release P100k to the accused until the total amount reached P1.15M. As security, respondent gave petitioner 14 open dated Hermosa Savings Bank checks with the assurance that if the entire amount is not paid within 1 year, petitioner can deposit the checks. In June 1997, petitioner together with Samson Ching demanded payment of the sums, but respondent refused to acknowledge the indebtedness. Thus, petitioner deposited all the checks in the bank of Samson Ching totaling P1.15M since all the money given by her to respondent came from Samson Ching. The checks were all returned for having been drawn against insufficient funds (DAIF). A verbal and written demand was made upon respondent, but to no avail. Hence, a complaint for violation of BP 22 was filed against respondent. MTC found respondent guilty of the charges against her. RTC affirmed. CA reversed the decision of the lower courts and acquitted respondent. ISSUE: WON respondent remains civilly liable for the sum of P1,150,000? HELD: NO. From the standpoint of its effects, a crime has a dual character: (1) as an offense against the State because of the disturbance of the social order and (2) as an offense against the private person injured by the crime unless it involves the crime of treason, rebellion, espionage, contempt and others (wherein no civil liability arises on the part of the offender either because there are no damages to be compensated or there is no private person injured by the crime). What gives rise to the civil liability is really the obligation of everyone to repair or to make whole the damage caused to another by reason of his act or omission, whether done intentionally or negligently and whether or not punishable by law. Extinction of penal action does not carry with it the eradication of civil liability, unless the extinction proceeds from a declaration in the final judgment that the fact from which the civil liability might arise did not exist. On one hand, as regards the criminal aspect of a violation of BP 22, suffice it to say that: the gravamen of BP 22 is the act of making and issuing a worthless check or one that is dishonored upon its presentment for payment [and] the accused failed to satisfy the amount of the check or make arrangement for its payment within 5 banking days from notice of dishonor. The act is malum prohibitum, pernicious and inimical to public welfare. Laws are created to achieve a goal intended to guide and prevent against an evil or mischief. Why and to whom the check was issued is irrelevant in On the other hand, the basic principle in civil liability ex delicto is that every person criminally liable is also civilly liable, crime being one of the five sources of obligations under the Civil Code. A person acquitted of a criminal charge, however, is not necessarily civilly free because the quantum of proof required in criminal prosecution (proof beyond reasonable doubt) is greater than that required for civil liability (mere preponderance of evidence). In order to be completely free from civil liability, a persons acquittal must be based on the fact that he did not commit the offense. If the acquittal is based merely on reasonable doubt, the accused may still be held civilly liable since this does not mean he did not commit the act complained of. It may only be that the facts proved did not constitute the offense charged. Acquittal will not bar a civil action in the following cases: (1) where the acquittal is based on reasonable doubt as only preponderance of evidence is required in civil cases; (2) where the court declared the accuseds liability is not criminal but only civil in nature and (3) where the civil liability does not arise from or is not based upon the criminal act of which the accused was acquitted. In this petition, we find no reason to ascribe any civil liability to respondent. As found by the CA, her supposed civil liability had already been fully satisfied and extinguished by payment. The statements of the appellate court leave no doubt that respondent, who was acquitted from the charges against her, had already been completely relieved of civil liability: Petitioner admitted having received cash payments from petitioner on a daily basis but argues that the same were applied to interest payments only. It however appears that petitioner was charging respondent with an exorbitant rate of interest. In any event, the cash payments made were recorded at the back of the cigarette cartons by petitioner in her own handwriting as testified to by respondent and her employees. Indeed, the daily cash payments reveal that respondent had already paid her obligation to petitioner in the amount of P5.78M and that she stopped making further payments when she realized that she had already paid such amount. Moreover, we find no evidence was presented by the prosecution to prove that there was a stipulation in writing that interest will be paid by respondent on her loan obligations, as required under Article 1956 of the Civil Code. The obligation of respondent has already been extinguished long before the encashment of the subject checks. A check is said to apply for account only when there is still a pre-existing obligation. In the case at bench, the pre-existing obligation was extinguished after full payment was made by respondent.

2. PRESTATIONS (ARTS. 1163-1168) 2.3 CONSEQUENCES OF FAILURE TO COMPLY W/ PRESTATION

BUENAVENTURA ANGELES V. URSULA TORRES CALASANZ G.R. No. L-42283 March 18, 1985 FACTS:

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS Ursula Torres Calasanz and Tomas Calasanz entered into a contract to sell a piece of land with Buenaventura Angeles and Teofila Juani for the amount of P3,920.00 plus 7% interest per annum. Angeles & Juani made a downpayment of P392.00 upon the execution of the contract. They promised to pay the balance in monthly installments of P 41.20 until fully paid, the installments being due and payable on the 19th day of each month. Angeles & Juani paid the monthly installments until July 1966, when their aggregate payment already amounted to P4,533.38. On numerous occasions, the defendants (Calsanz) accepted and received delayed installment payments from the plaintiffs (Angeles & Juani). In 1966, the defendants-appellants wrote the plaintiffs a letter requesting the remittance of past due accounts. Defendants cancelled the said contract because the plaintiffs failed to meet subsequent payments. The plaintiffs' letter with their plea for reconsideration of the said cancellation was denied by the defendants The plaintiffs filed Civil Case to compel the defendants to execute in their favor the final deed of sale alleging inter alia that after computing all subsequent payments for the land in question, they found out that they have already paid the total amount of P4,533.38 including interests, realty taxes and incidental expenses for the registration and transfer of the land. The defendants alleged that the plaintiffs violated par. 6 of the contract to sell when they failed to pay and/or offer to pay the monthly installments corresponding to the month of August 1966 for more than 5 months, thereby constraining the defendants-appellants to cancel the said contract. ISSUE: WON the contract to sell has been validly cancelled by the defendants? HELD: NO. Article 1191 is explicit. In reciprocal obligations, either party the right to rescind the contract upon the failure of the other to perform the obligation assumed thereunder. Moreover, there is nothing in the law that prohibits the parties from entering into an agreement that violation of the terms of the contract would cause its cancellation even without court intervention. Well settled is, however, the rule that a judicial action for the rescission of a contract is not necessary where the contract provides that it may be revoked and cancelled for violation of any of its terms and conditions. The rule is that it is not always necessary for the injured party to resort to court for rescission of the contract when the contract itself provides that it may be rescinded for violation of its terms and conditions, was qualified by this Court in University of the Philippines v. De los Angeles: Of course, it must be understood that the act of a party in treating a contract as cancelled or resolved on account of infractions by the other contracting party must be made known to the other and is always provisional, being ever subject to scrutiny and review by the proper court. If the other party denies that rescission is justified, it is free to resort to judicial action in its own behalf, and bring the matter to court. Then, should the court, after due hearing, decide that the resolution of the contract was not warranted, the responsible party will be sentenced to damages; in the contrary case, the resolution will be affirmed, and the consequent indemnity awarded to the party prejudiced. In other words, the party who deems the contract violated may consider it resolved or rescinded, and act accordingly, without previous court action, but it proceeds at its own risk. For it is only the final judgment of the corresponding court that will conclusively and finally settle whether the action taken was or was not correct in law. The right to rescind the contract for non-performance of one of its stipulations, therefore, is not absolute. The general rule is that rescission of a contract will not be permitted for a slight or casual breach, but only for such substantial and fundamental breach as would defeat the very object of the parties in making the agreement. The breach of the contract adverted to by the defendants is so slight and casual when we consider that apart from the initial downpayment of P392.00 the plaintiffs had already paid the monthly installments for a period of almost 9 years. In other words, in only a short time, the entire obligation would have been paid. To sanction the rescission made by the defendants-appellants will work injustice to the plaintiffs and would unjustly enrich the defendants. We agree with the plaintiffs that when the defendants, instead of availing of their alleged right to rescind, accepted and received delayed payments of installments, though the plaintiffs have been in arrears beyond the grace period mentioned in paragraph 6 of the contract, the defendants waived and are now estopped from exercising their alleged right of rescission. Plaintiffs contend that the contract herein is a contract of adhesion. We agree. The contract to sell entered into by the parties has some characteristics of a contract of adhesion. The defendants drafted and prepared the contract. The plaintiffs, eager to acquire a lot upon which they could build a home, affixed their signatures and assented to the terms and conditions of the contract. They had no opportunity to question nor change any of the terms of the agreement. It was offered to them on a "take it or leave it" basis. While generally, stipulations in a contract come about after deliberate drafting by the parties thereto, there are certain contracts almost all the provisions of which have been drafted only by one party, usually a corporation. Such contracts are called contracts of adhesion, because the only participation of the party is the signing of his signature or his "adhesion" thereto. Insurance contracts, bills of lading, contracts of sale of lots on the installment plan fall into this category. The contract to sell, being a contract of adhesion, must be construed against the party causing it.

ADELFA S. RIVERA V. FIDELA DEL ROSARIO G.R. No. 144934. January 15, 2004 FACTS: Respondents Fidela, et al. were the registered owners of a parcel of land. Fidela borrowed P250k from Mariano Rivera and to secure the loan, she and Mariano Rivera agreed to execute a deed of REM and an agreement to sell the land. Mariano went to his lawyer to have 3 documents drafted: the Deed of REM, a Kasunduan (Agreement to Sell), and a Deed of Absolute Sale. The Kasunduan provided that the children of Mariano Rivera, herein petitioners, would purchase the land for a consideration of P2M, to be paid in 3 installments. It also provided that the Deed of Absolute Sale would be executed only after the 2nd installment is paid and a postdated check for the last installment is deposited with Fidela. Mariano Rivera then went to his lawyer bringing with him the signed documents. He also brought Fidela and her son Oscar, so that the latter two may sign the mortgage and the

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS Kasunduan there. Although Fidela intended to sign only the Kasunduan and the REM, she inadvertently affixed her signature on all 3 documents. Mariano then gave Fidela the amount for the 1st installment. Later, he also gave Fidela a check for the 2nd installment. Mariano also gave Oscar several amounts upon the latters demand for the payment of the balance despite his lack of authority to receive payments under the Kasunduan. Fidela entrusted the owners copy of TCT to Mariano to guarantee compliance with the Kasunduan. When Mariano unreasonably refused to return the TCT, respondents caused the annotation on TCT of an Affidavit of Loss of the owners duplicate copy of the title. However, Mariano then registered the Deed of Absolute Sale and got a new TCT. Respondents then filed a complaint asking that the Kasunduan be rescinded for failure of the Riveras to comply with its conditions, with damages. They also sought the annulment of the Deed of Absolute Sale on the ground of fraud. Respondents claimed that Fidela never intended to enter into a deed of sale at the time of its execution and that she signed the said deed on the mistaken belief that she was merely signing copies of the Kasunduan. ISSUE: WON the Deed of Absolute Sale is valid and binding? HELD: NO. The deed is void in its entirety. Rescission of reciprocal obligations under Article 1191 of the New Civil Code should be distinguished from rescission of contracts under Article 1383 of the same Code. Both presuppose contracts validly entered into as well as subsisting, and both require mutual restitution when proper, nevertheless they are not entirely identical. While Article 1191 uses the term rescission, the original term used in Article 1124 of the old Civil Code, from which Article 1191 was based, was resolution. Resolution is a principal action that is based on breach of a party, while rescission under Article 1383 is a subsidiary action limited to cases of rescission for lesion under Article 1381 of the New Civil Code. Obviously, the Kasunduan does not fall under any of those situations mentioned in Article 1381. Consequently, Article 1383 is inapplicable. Hence, we rule in favor of the respondents. May the contract entered into between the parties, however, be rescinded based on Article 1191? A careful reading of the Kasunduan reveals that it is in the nature of a contract to sell, as distinguished from a contract of sale. In a contract of sale, the title to the property passes to the vendee upon the delivery of the thing sold; while in a contract to sell, ownership is, by agreement, reserved in the vendor and is not to pass to the vendee until full payment of the purchase price. In a contract to sell, the payment of the purchase price is a positive suspensive condition, the failure of which is not a breach, casual or serious, but a situation that prevents the obligation of the vendor to convey title from acquiring an obligatory force. Respondents in this case bound themselves to deliver a deed of absolute sale and clean title covering Lot No. 1083-C after petitioners have made the second installment. This promise to sell was subject to the fulfillment of the suspensive condition that petitioners pay P750,000 on August 31, 1987, and deposit a postdated check for the third installment of P1M. Petitioners, however, failed to complete payment of the second installment. The non-fulfillment of the condition rendered the contract to sell

ineffective and without force and effect. It must be stressed that the breach contemplated in Article 1191 of the New Civil Code is the obligors failure to comply with an obligation already extant, not a failure of a condition to render binding that obligation. Failure to pay, in this instance, is not even a breach but an event that prevents the vendors obligation to convey title from acquiring binding force. Hence, the agreement of the parties in the instant case may be set aside, but not because of a breach on the part of petitioners for failure to complete payment of the second installment. Rather, their failure to do so prevented the obligation of respondents to convey title from acquiring an obligatory force. Coming now to the matter of prescription. Contrary to petitioners assertion, we find that prescription has not yet set in. Article 1391 states that the action for annulment of void contracts shall be brought within four years. This period shall begin from the time the fraud or mistake is discovered. Here, the fraud was discovered in 1992 and the complaint filed in 1993. Thus, the case is well within the prescriptive period. SPOUSES BARREDO V. SPOUSES LEAO [G.R. No. 156627. June 4, 2004] FACTS: Barredo Spouses bought a house and lot with the proceeds of a P50k loan from the SSS which was payable in 25 years and an P88k loan from the Apex Mortgage and Loans Corporation which was payable in 20 years. To secure the twin loans, they executed a first mortgage over the house and lot in favor of SSS and a second one in favor of Apex. Barredo Spouses later sold their house and lot to respondents Spouses Leao by way of a Conditional Deed of Sale with Assumption of Mortgage. The Leao Spouses would pay the Barredo Spouses P200k, P100k of which would be payable on July 15, 1987, while the balance of P100k would be paid in 10 equal monthly installments after the signing of the contract. The Leao Spouses would also assume the first and second mortgages and pay the monthly amortizations to SSS and Apex beginning July 1987 until both obligations are fully paid. In accordance with the agreement, the purchase price of P200k was paid to the Barredo Spouses who turned over the possession of the house and lot in favor of the Leao Spouses. 2 years later, Barredo Spouses initiated a complaint before the RTC seeking the rescission of the contract on the ground that the Leao Spouses despite repeated demands failed to pay the mortgage amortizations to the SSS and Apex, causing the Barredo Spouses great and irreparable damage. The Leao Spouses, however, answered that they were up-to-date with their amortization payments to Apex but were not able to pay the SSS amortizations because their payments were refused upon the instructions of the Barredo Spouses. Meanwhile, allegedly in order to save their good name, credit standing and reputation, the Barredo Spouses took it upon themselves to settle the mortgage loans and paid the SSS. They also settled the mortgage loan with Apex. They also paid the real estate property taxes for the 1987 up to 1990. Petitioners argue that the terms of the agreement called for the strict compliance of 2 equally essential and material obligations on the part of the Leao Spouses, namely, the payment of the P200,000.00 to them and the payment of the mortgage amortizations to the SSS and Apex. Respondents Leao Spouses, however, contend that they were only obliged to assume the amortization payments of the Barredo Spouses with

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS the SSS and Apex, which they did upon signing the agreement. The contract does not stipulate as a condition the full payment of the SSS and Apex mortgages. ISSUE: WON THE BARREDO SPOUSES MAY RESCIND THE CONTRACT, ON THE GROUND OF NON-FULFILLMENT OF THE PRESTATIONS? HELD: NO. A careful reading of the pertinent provisions of the agreement readily shows that the principal object of the contract was the sale of the Barredo house and lot, for which the Leao Spouses gave a down payment of P100,000.00 as provided for in par. 1 of the contract, and thereafter ten (10) equal monthly installments amounting to another P100,000.00, as stipulated in par. 2 of the same agreement. The assumption of the mortgages by the Leao Spouses over the mortgaged property and their payment of amortizations are just collateral matters which are natural consequences of the sale of the said mortgaged property. To include the full payment of the obligations with the SSS and Apex as a condition would be to unnecessarily stretch and put a new meaning to the provisions of the agreement. For, as a general rule, when the terms of an agreement have been reduced to writing, such written agreement is deemed to contain all the terms agreed upon and there can be, between the parties and their successors-in-interest, no evidence of such terms other than the contents of the written agreement. And, it is a familiar doctrine in obligations and contracts that the parties are bound by the stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions they have agreed to, which is the law between them, the only limitation being that these stipulations, clauses, terms and conditions are not contrary to law, morals, public order or public policy. Not being repugnant to any legal proscription, the agreement entered into by the parties must be respected and each is bound to fulfill what has been expressly stipulated therein. But even if we consider the payment of the mortgage amortizations to the SSS and Apex as a condition on which the sale is based on, still rescission would not be available since non-compliance with such condition would just be a minor or casual breach thereof as it does not defeat the very object of the parties in entering into the contract. A cursory reading of the agreement easily reveals that the main consideration of the sale is the payment of P200K to the vendors within the period agreed upon. The assumption of mortgage by the Leao Spouses is a natural consequence of their buying a mortgaged property. In fact, the Barredo Spouses do not stand to benefit from the payment of the amortizations by the Leao Spouses directly to the SSS and Apex simply because the Barredo Spouses have already parted with their property, for which they were already fully compensated in the amount of P200K. If the Barredo Spouses were really protective of their reputation and credit standing, they should have sought the consent, or at least notified the SSS and Apex of the assumption by the Leao Spouses of their indebtedness. Besides, in ordering rescission, the trial court should have likewise ordered the Barredo Spouses to return the P200K they received as purchase price plus interests. Art. 1385 of the Civil Code provides that [r]escission creates the obligation to return the things which were the object of the contract, together with their fruits, and the price with its interest. The vendor is therefore obliged to return the purchase price paid to him by the buyer if the latter rescinds the sale. Thus, where a contract is rescinded, it is the duty of the court to require both parties to surrender that which they have respectively received and place each other as far as practicable in his original situation.

GENEROSO V. VILLANUEVA V. STATE OF GERARDO L. GONZAGA [G.R. No. 157318, August 09, 2006] FACTS: Petitioners Generoso and Raul Villanueva bought parcels of land from the estate of Gonzaga (through its judicial adminsitratrix). The lots were then mortgaged with the PNB. In their agreement, the parties stipulated that the estate of Gonzaga would cause the release of the lots from PNB at the earliest possible time; that the Villanuevas will pay P100k upon signing the agreement, P191k on Jan 1990, then P194k upon the approval by the PNB of the release of the lots. It was also stipulated that upon payment of 60% of the purchase price, the Villanuevas may start to introduce improvements in the area if they so desire. Lastly, they agreed that upon the release by PNB of the lots, the Estate of Gonzaga shall immediately execute a Deed of Sale in favor of the Villanuevas. As stipulated in the agreement, petitioners introduced improvements after paying 60% of the total purchase price. Petitioners then requested permission from respondent Administratrix to use the premises for the next milling season. Respondent refused on the ground that petitioners cannot use the premises until full payment of the purchase price. Petitioners informed respondent that their immediate use of the premises was absolutely necessary and that any delay will cause them substantial damages. Respondent remained firm in her refusal, and demanded that petitioners stop using the lots as a transloading station to service the Victorias Milling Company unless they pay the full purchase price. In a letter-reply, petitioners assured respondent of their readiness to pay the balance but reminded respondent of her obligation to redeem the lots from mortgage with the PNB. Petitioners gave respondent 10 days within which to do so. Respondent Administratrix wrote petitioners informing them that the PNB had agreed to release the lots from mortgage. She demanded payment of the balance of the purchase price. Petitioners demanded that respondent show the clean titles to the lots first before they pay the balance of the purchase price. Respondent Administratrix then executed a Deed of Rescission rescinding the MOA on two grounds: (1) petitioners failed to pay the balance of the purchase price despite notice of the lots release from mortgage, and (2) petitioners violated the MOA by using the lots as a transloading station without permission from the respondents. Petitioners then filed a complaint against respondents for breach of contract, specific performance and damages before the RTC. Petitioners alleged that respondents delayed performance of their obligation by unreasonably failing to secure the release of the lots from mortgage with the PNB. ISSUE: WON respondents failed to comply with their reciprocal obligation of securing the release of the lots from the PNB mortgage? HELD: YES, rescission was invalid. CA erred in ruling that respondents had already fulfilled their obligation to cause the release of the lots from the PNB at the time they demanded payment of the balance of the purchase price. A reading of PNBs letter of approval clearly shows that the approval was conditional. 3 conditions were laid down by the bank before the lots could be finally released from mortgage. It was

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS therefore premature for respondents to demand payment of the balance of the purchase price from the petitioners and, failing in that, to rescind the MOA. Moreover, there is no legal basis for the rescission. The remedy of rescission under Art. 1191 is predicated on a breach of faith by the other party that violates the reciprocity between them. We have held in numerous cases that the remedy does not apply to contracts to sell. In a contract to sell, title remains with the vendor and does not pass on to the vendee until the purchase price is paid in full. Thus, in a contract to sell, the payment of the purchase price is a positive suspensive condition. Failure to pay the price agreed upon is not a mere breach, casual or serious, but a situation that prevents the obligation of the vendor to convey title from acquiring an obligatory force. This is entirely different from the situation in a contract of sale, where non-payment of the price is a negative resolutory condition. The effects in law are not identical. In a contract of sale, the vendor has lost ownership of the thing sold and cannot recover it, unless the contract of sale is rescinded and set aside. In a contract to sell, however, the vendor remains the owner for as long as the vendee has not complied fully with the condition of paying the purchase price. If the vendor should eject the vendee for failure to meet the condition precedent, he is enforcing the contract and not rescinding it. Article 1592 speaks of non-payment of the purchase price as a resolutory condition. It does not apply to a contract to sell. As to Article 1191, it is subordinated to the provisions of Article 1592 when applied to sales of immovable property. Neither provision is applicable [to a contract to sell]. The MOA between petitioners and respondents is a conditional contract to sell. Ownership over the lots is not to pass to the petitioners until full payment of the purchase price. Petitioners obligation to pay, in turn, is conditioned upon the release of the lots from mortgage with the PNB to be secured by the respondents. Although there was no express provision regarding reserved ownership until full payment of the purchase price, the intent of the parties in this regard is evident from the provision that a deed of absolute sale shall be executed only when the lots have been released from mortgage and the balance paid by petitioners. Since ownership has not been transferred, no further legal action need have been taken by the respondents, except an action to recover possession in case petitioners refuse to voluntarily surrender the lots. The records show that the lots were finally released from mortgage in July 1991. Petitioners have always expressed readiness to pay the balance of the purchase price once that is achieved. Hence, petitioners should be allowed to pay the balance now, if they so desire, since it is established that respondents demand for them to pay in April 1991 was premature. However, petitioners may not demand production by the respondents of the titles to the lots as a condition for their payment. It was not required under the MOA.

offended party, Loreto Dionela, reading as follows: SA IYO WALANG PAKINABANG DUMATING KA DIYAN-WALAKANG PADALA DITO KAHIT BULBUL MO Loreto Dionela alleges that the defamatory words on the telegram sent to him not only wounded his feelings but also caused him undue embarrassment and affected adversely his business as well because other people have come to know of said defamatory words. Defendant corporation as a defense, alleges that the additional words in Tagalog was a private joke between the sending and receiving operators and that they were not addressed to or intended for plaintiff and therefore did not form part of the telegram and that the Tagalog words are not defamatory. The telegram sent through its facilities was received in its station at Legaspi City. Nobody other than the operator manned the teletype machine which automatically receives telegrams being transmitted. The said telegram was detached from the machine and placed inside a sealed envelope and delivered to plaintiff, obviously as is. The additional words in Tagalog were never noticed and were included in the telegram when delivered. RTC ruled in favor of Dionela, holding that the additional Tagalog words are libelous. It ruled that there was sufficient publication because the office file of the defendant containing copies of telegrams received are open and held together only by a metal fastener. Moreover, they are open to view and inspection by third parties. RTC also held that the defendant is sued directly not as an employer. The business of the defendant is to transmit telegrams. It will open the door to frauds and allow the defendant to act with impunity if it can escape liability by the simple expedient of showing that its employees acted beyond the scope of their assigned tasks. ISSUE: WON Petitioner-employer should answer directly and primarily for the civil liability arising from the criminal act of its employee. HELD: YES. The action for damages was filed in the lower court directly against respondent corporation not as an employer subsidiarily liable under the provisions of Article 1161 of the New Civil Code in relation to Art. 103 of the Revised Penal Code. The cause of action of the private respondent is based on Arts. 19 and 20 of the New Civil Code, as well as on respondent's breach of contract thru the negligence of its own employees. Petitioner is a domestic corporation engaged in the business of receiving and transmitting messages. Everytime a person transmits a message through the facilities of the petitioner, a contract is entered into. Upon receipt of the rate or fee fixed, the petitioner undertakes to transmit the message accurately. There is no question that in the case at bar, libelous matters were included in the message transmitted, without the consent or knowledge of the sender. There is a clear case of breach of contract by the petitioner in adding extraneous and libelous matters in the message sent to the private respondent. As a corporation, the petitioner can act only through its employees. Hence the acts of its employees in receiving and transmitting messages are the acts of the petitioner. To hold that the petitioner is not liable directly for the acts of its employees in the pursuit of petitioner's business is to deprive the general public availing of the services of the petitioner of an effective and adequate remedy. In most cases, negligence must be proved in order that plaintiff may recover. However, since negligence may be hard to substantiate in some cases, we may apply the doctrine of RES IPSA LOQUITUR (the thing speaks for itself), by considering the presence of facts or circumstances surrounding the injury.

3. BREACH (ARTS/ 1169-1174) 3.1.2 CULPA

RADIO COMM. OF THE PHILS., INC. (RCPI). V. CA & LORETO DIONELA G.R. No. L-44748 August 29, 1986 FACTS: The basis of the complaint against the defendant corporation is a telegram sent through its Manila Office to the

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS shall be made by the employees of the Association. Pursuant to this above-mentioned Rule, a concrete vault was provided the day before the interment, and was, on the same day, installed by private respondent's employees in the grave which was dug earlier. After the burial, the vault was covered by a cement lid. Petitioners however claim that private respondent breached its contract with them as the latter held out in the brochure it distributed that the lot may hold a single or double internment underground, in a sealed concrete vault. Petitioners claim that the vault provided by private respondent was not sealed, that is, not waterproof. Consequently, water seeped through the cement enclosure and damaged everything inside it. We do not agree. There was no stipulation in the Deed of Sale and Certificate of Perpetual Care and in the Rules and Regulations of the Manila Memorial Park Cemetery, Inc. that the vault would be waterproof. Private respondent's witness, Mr. Dexter Heuschkel, explained that the term "sealed" meant "closed." Moreover, it is also quite clear that "sealed" cannot be equated with "waterproof". Well settled is the rule that when the terms of the contract are clear and leave no doubt as to the intention of the contracting parties, then the literal meaning of the stipulation shall control. Contracts should be interpreted according to their literal meaning and should not be interpreted beyond their obvious intendment. We hold, therefore, that private respondent did not breach the tenor of its obligation to the Syquias. While this may be so, can private respondent be liable for culpa aquiliana for boring the hole on the vault? It cannot be denied that the hole made possible the entry of more water and soil than was natural had there been no hole. The law defines negligence as the "omission of that diligence which is required by the nature of the obligation and corresponds with the circumstances of the persons, of the time and of the place." In the absence of stipulation or legal provision providing the contrary, the diligence to be observed in the performance of the obligation is that which is expected of a good father of a family. FAR EAST BANK AND TRUST COMPANY V. C.A. & LUIS A. LUNA G.R. No. 108164 February 23, 1995 FACTS: Private respondent Luis A. Luna applied for, and was accorded, a FAREASTCARD issued by petitioner FEBTC. Upon his request, the bank also issued a supplemental card to private respondent Clarita S. Luna. Later, Clarita lost her credit card. FEBTC was informed. In order to replace the lost card, Clarita submitted an affidavit of loss. In cases of this nature, the bank's internal security procedures and policy would be to record the lost card, along with the principal card, as a "Hot Card" or "Cancelled Card" in its master file. Luis then tendered a despedida lunch for a close friend, a Filipino-American, and another guest at the Bahia Rooftop Restaurant of the Hotel Intercontinental Manila. To pay for the lunch, Luis presented his fareastcard to the attending waiter who promptly had it verified through a telephone call to the bank's Credit Card Department. Since the card was not honored, Luis was forced to pay in cash the bill amounting to P588.13. Naturally, Luis felt embarrassed by this incident. Private respondent Luis Luna, through counsel, demanded from FEBTC the payment of damages. Adrian V. Festejo, a vice-president of the bank, expressed the bank's apologies to Luis, admitting that: An investigation of your case revealed that FAREASTCARD failed to inform you about its security policy. Furthermore, an overzealous employee of the Bank's

JUAN J. SYQUIA V. C.A. & MANILA MEMORIAL PARK CEMETERY, INC. G.R. No. 98695 January 27, 1993 FACTS: Pursuant to a Deed of Sale and an Interment Order executed between plaintiff and defendant, Juan J. Syquia (father of deceased Vicente Syquia) authorized and instructed defendant to inter the remains of the deceased in the Manila Memorial Park Cemetery conformably and in accordance with defendant's interment procedures. After a few months, preparatory to transferring the said remains to a newly purchased family plot also at the Manila Memorial Park Cemetery, the concrete vault encasing the coffin of the deceased was removed from its niche underground with the assistance of certain employees of defendant. As the concrete vault was being raised to the surface, plaintiffs discovered that the concrete vault had a hole approximately 3 inches in diameter near the bottom of one of the walls closing out the width of the vault on one end and that for a certain length of time, water drained out of the hole. Pursuant to an authority granted by the MTC, plaintiffs, with the assistance of licensed morticians and certain personnel of defendant, caused the opening of the concrete vault. Upon opening the vault, the following became apparent: (a) the interior walls of the concrete vault showed evidence of total flooding; (b) the coffin was entirely damaged by water, filth and silt causing the wooden parts to warp and separate and to crack the viewing glass panel located directly above the head and torso of the deceased; (c) the entire lining of the coffin, the clothing of the deceased, and the exposed parts of the deceased's remains were damaged and soiled by the action of the water and silt and were also coated with filth. Plaintiffs filed a case for damages, based on the alleged unlawful and malicious breach by the defendant of its obligation to deliver a defect-free concrete vault designed to protect the remains of the deceased and the coffin against the elements which resulted in the desecration of deceased's grave and in the alternative, because of defendant-appellee's gross negligence conformably to Article 2176 of the New Civil Code in failing to seal the concrete vault. ISSUE: WON DEFENDANT IS LIABLE FOR QUASI-DELICT? HELD: NO, there was no fault or negligence on the part of the defendant that would render him liable for quasi-delict. Although a pre-existing contractual relation between the parties does not preclude the existence of a culpa aquiliana, we find no reason to disregard the respondent's Court finding that there was no negligence. In this case, it has been established that the Syquias and the Manila Memorial Park Cemetery, Inc., entered into a contract entitled "Deed of Sale and Certificate of Perpetual Care." That agreement governed the relations of the parties and defined their respective rights and obligations. Hence, had there been actual negligence on the part of the Manila Memorial Park Cemetery, Inc., it would be held liable not for a quasi-delict or culpa aquiliana, but for culpa contractual as provided by Article 1170 of the Civil Code. The Manila Memorial Park Cemetery, Inc. bound itself to provide the concrete box to be sent in the interment. Rule 17 of the Rules and Regulations of private respondent provides that: Rule 17. Every earth interment shall be made enclosed in a concrete box, or in an outer wall of stone, brick or concrete, the actual installment of which

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS Credit Card Department did not consider the possibility that it may have been you who was presenting the card at that time (for which reason, the unfortunate incident occurred). Luna then filed a case for damages in the RTC, which rendered a decision against FEBTC, and awarded moral damages. ISSUE: WON FEBTC IS LIABLE FOR QUASI-DELICT? HELD: NO. In culpa contractual, moral damages may be recovered where the defendant is shown to have acted in bad faith or with malice in the breach of the contract. Bad faith, in the context of Article 2220, includes gross, but not simple, negligence. Exceptionally, in a contract of carriage, moral damages are also allowed in case of death of a passenger attributable to the fault (which is presumed) of the common carrier. Concededly, the bank was remiss in indeed neglecting to personally inform Luis of his own card's cancellation. Nothing in the findings of the trial court and the appellate court, however, can sufficiently indicate any deliberate intent on the part of FEBTC to cause harm to private respondents. Neither could FEBTC's negligence in failing to give personal notice to Luis be considered so gross as to amount to malice or bad faith. Malice or bad faith implies a conscious and intentional design to do a wrongful act for a dishonest purpose or moral obliquity; it is different from the negative idea of negligence in that malice or bad faith contemplates a state of mind affirmatively operating with furtive design or ill will. We are not unaware of the previous rulings of this Court, sanctioning the application of Article 21, in relation to Article 2217 and Article 2219 7 of the Civil Code to a contractual breach similar to the case at bench. Article 21 of the Code, it should be observed, contemplates a conscious act to cause harm. Thus, even if we are to assume that the provision could properly relate to a breach of contract, its application can be warranted only when the defendant's disregard of his contractual obligation is so deliberate as to approximate a degree of misconduct certainly no less worse than fraud or bad faith. Most importantly, Article 21 is a mere declaration of a general principle in human relations that clearly must, in any case, give way to the specific provision of Article 2220 of the Civil Code authorizing the grant of moral damages in culpa contractual solely when the breach is due to fraud or bad faith. Justice Jose B.L. Reyes, in his ponencia in Fores vs. Miranda, explained: Moral damages are not recoverable in damage actions predicated on a breach of the contract of transportation, in view of Articles 2219 and 2220 of the new Civil Code. By contrasting the provisions of these two articles it immediately becomes apparent that: (a) In case of breach of contract (including one of transportation) proof of bad faith or fraud (dolus), i.e., wanton or deliberately injurious conduct, is essential to justify an award of moral damages; and (b) That a breach of contract can not be considered included in the descriptive term "analogous cases" used in Art. 2219; not only because Art. 2220 specifically provides for the damages that are caused contractual breach, but because the definition of quasi-delict in Art. 2176 of the Code expressly excludes the cases where there is a "preexisitng contractual relations between the parties." The distinction between fraud, bad faith or malice in the sense of deliberate or wanton wrong doing and negligence (as mere

carelessness) is too fundamental in our law to be ignored (Arts. 1170-1172); their consequences being clearly differentiated by the Code. It is to be presumed, in the absence of statutory provision to the contrary, that this difference was in the mind of the lawmakers when in Art. 2220 they limited recovery of moral damages to breaches of contract in bad faith. It is true that negligence may be occasionally so gross as to amount to malice; but the fact must be shown in evidence, and a carrier's bad faith is not to be lightly inferred from a mere finding that the contract was breached through negligence of the carrier's employees. The Court has not in the process overlooked another rule that a quasi-delict can be the cause for breaching a contract that might thereby permit the application of applicable principles on tort even where there is a pre-existing contract between the plaintiff and the defendant. This doctrine, unfortunately, cannot improve private respondents' case for it can aptly govern only where the act or omission complained of would constitute an actionable tort independently of the contract. The test (whether a quasi-delict can be deemed to underlie the breach of a contract) can be stated thusly: Where, without a pre-existing contract between two parties, an act or omission can nonetheless amount to an actionable tort by itself, the fact that the parties are contractually bound is no bar to the application of quasi-delict provisions to the case. Here, private respondents' damage claim is predicated solely on their contractual relationship; without such agreement, the act or omission complained of cannot by itself be held to stand as a separate cause of action or as an independent actionable tort.

3.1.3 MORA / DEFAULT A. BY THE OBLIGOR / DEBTOR

BRICKTOWN DEVELOPMENT CORP. V. AMOR TIERRA DEVT CORP. G.R. No. 112182 December 12, 1994 FACTS: Bricktown Devt Corp. executed 2 Contracts to Sell in favor of Amor Tierra Devt Corp. covering 96 residential lots in Paraaque. The total price of P21M was stipulated to be paid in 3 installments and the balance of P11.5M to be paid by means of an assumption of Bricktown's mortgage liability to Philippine Savings Bank or, alternatively, to be made payable in cash. Later, the parties executed a Supplemental Agreement providing that private respondent would additionally pay to Bricktown the amounts representing interest on the balance of downpayments and the interest paid by Bricktown to PSB in updating the bank loan. Private respondent was only able to pay petitioner corporation the sum of P1.3M. In the meanwhile, however, the parties continued to negotiate for a possible modification of their agreement, although nothing conclusive would appear to have ultimately been arrived at. Finally, Bricktown, sent private respondent a "Notice of Cancellation of Contract" on account of the latter's continued failure to pay the installment due 30 June 1981 and the interest on the unpaid balance of the stipulated initial payment. Bricktown advised Amor Tierra, however, that Amor Tierra still had the right to pay its arrearages within 30 days from receipt of the notice "otherwise the actual cancellation of the contract would take place." Several months later, Amor Tierra, through counsel, demanded the refund of it's various payments to Bricktown, with interest within fifteen days from receipt of said letter, or, in

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS lieu of a cash payment, to assign to private respondent an equivalent number of unencumbered lots at the same price fixed in the contracts. The demand, not having been heeded, Amor Tierra commenced an action against Bricktown. RTC declared the K to sell and the supplemental agreement rescinded, and ordered Bricktown to return to Amor Tierra the amounts the latter have paid, with interest. CA affirmed. ISSUE: WON THE K TO SELL WERE VALIDLY RESCINDED? HELD: YES, Bricktown acted well within its right, in accordance with the agreement. Admittedly, the terms of payment agreed upon by the parties were not met by Amor Tierra. Of a total selling price of P21M, Amor Tierra was only able to remit the sum of P1.3M which was even short of the stipulated initial payment of P2.2M. No additional payments, it would seem, were made. A notice of cancellation was ultimately made months after the lapse of the contracted grace period. Paragraph 15 of the Contracts to Sell provided thusly: Should the PURCHASER fail to pay when due any of the installments mentioned in stipulation No. 1 above, the OWNER shall grant the purchaser a sixty (60)-day grace period within which to pay the amount/s due, and should the PURCHASER still fail to pay the due amount/s within the 60-day grace period, the PURCHASER shall have the right to ex-parte cancel or rescind this contract, provided, however, that the actual cancellation or rescission shall take effect only after the lapse of thirty (30) days from the date of receipt by the PURCHASER of the notice of cancellation of this contract or the demand for its rescission by a notarial act, and thereafter, the OWNER shall have the right to resell the lot/s subject hereof to another buyer and all payments made, together with all improvements introduced on the aforementioned lot/s shall be forfeited in favor of the OWNER as liquidated damages, and in this connection, the PURCHASER obligates itself to peacefully vacate the aforesaid lot/s without necessity of notice or demand by the OWNER. A grace period is a right, not an obligation, of the debtor. When unconditionally conferred, such as in this case, the grace period is effective without further need of demand either calling for the payment of the obligation or for honoring the right. The grace period must not be likened to an obligation, the non-payment of which, under Article 1169 of the Civil Code, would generally still require judicial or extrajudicial demand before "default" can be said to arise. Verily, in the case at bench, the sixty-day grace period under the terms of the contracts to sell became ipso facto operative from the moment the due payments were not met at their stated maturities. On this score, the provisions of Article 1169 of the Civil Code would find no relevance whatsoever. The cancellation of the contracts to sell by petitioner corporation accords with the contractual covenants of the parties, and such cancellation must be respected. It may be noteworthy to add that in a contract to sell, the non-payment of the purchase price (which is normally the condition for the final sale) can prevent the obligation to convey title from acquiring any obligatory force. The forfeiture of the payments thus far remitted under the cancelled contracts in question, given the factual findings of both the trial court and the appellate court, must be viewed differently. Petitioners do not deny the fact that there has indeed been a constant dialogue between the parties during the period of their juridical relation.

In fine, while we must conclude that petitioner corporation still acted within its legal right to declare the contracts to sell rescinded or cancelled, considering, nevertheless, the peculiar circumstances found to be extant by the trial court, confirmed by the Court of Appeals, it would be unconscionable, in our view, to likewise sanction the forfeiture by petitioner corporation of payments made to it by private respondent. Indeed, in the opening statement of this ponencia, we have intimated that the relationship between parties in any contract must always be characterized and punctuated by good faith and fair dealing. Judging from what the courts below have said, petitioners did fall well behind that standard. We do not find it equitable, however, to adjudge any interest payment by petitioners on the amount to be thus refunded, computed from judicial demand, for, indeed, private respondent should not be allowed to totally free itself from its own breach. BERLIN TAGUBA V. MARIA PERALTA VDA. DE DE LEON G.R. No. L-59980 October 23, 1984 FACTS: Berlin Taguba married to Sebastiana Domingo (petitioner) is the owner of a residential lot in Isabela. Spouses Pedro Asuncion and Marita Lungab, (also petitioners) and herein private respondent Maria Peralta Vda. de De Leon, were separately occupying portions of the aforementioned lot as lessees. Berlin Taguba sold a portion of the said lot to private respondent Maria Peralta Vda de De Leon. The portion sold comprises the area occupied by the Asuncions and private respondent Vda de De Leon. The deed evidencing said sale was denominated as "Deed of Conditional Sale," which stipulated that a downpayment shall be made upon signing of the contract, then P1k a month installments shall be made. It also provided that if the vendee fails to pay the whole balance by December 1972, she shall be given 6 months extension period but with legal interest, after which the vendor may increase the purchase price. De Leon alleges that she had already paid the sum of P12,500 and had tendered payment of the balance of P5,500 to complete the stipulated purchase price of P18k to petitioner within the grace period but the latter refused to receive payment. Private respondent then instituted a complaint for Specific Performance with Preliminary Mandatory Injunction with Damages against Spouses Berlin Taguba and Sebastiana Domingo. Spouses Taguba admitted the sale of the property, but claimed that private respondent failed to comply with her obligation under the Deed of Conditional Sale despite the several extensions granted her, by reason of which petitioner was compelled but with the express knowledge and consent and even upon the proposal of private respondent, to negotiate the sale of a portion of the property sold, to the Spouses Asuncion who were actually in possession thereof. ISSUE: WON THE DEED OF CONDITIONAL SALE WAS VALIDLY RESCINDED? HELD: NO. The contract of sale between petitioner and private respondent was absolute in nature. Despite the denomination of the deed as a "Deed of Conditional Sale" a reading of the conditions therein set forth reveals the contrary. Nowhere in the said contract in question could we find a proviso or stipulation to the effect that title to the property sold is reserved in the vendor until full payment of the purchase price. There is also no stipulation giving the vendor the

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS right to unilaterally rescind the contract the moment the vendee fails to pay within a fixed period. Indeed, a reading of the contract in its entirety would show that the only right of petitioner Taguba as vendor was to collect interest at the legal rate if private respondent fails to pay the full purchase price, and to increase the price if vendee still fails to pay within the six months grace period. Considering, therefore, the nature of the transaction between petitioner Taguba and private respondent, which We affirm and sustain to be a contract of sale, absolute in nature, the applicable provision is Article 1592 of the New Civil Code. In the case at bar, it is undisputed that petitioner Taguba never notified private respondent by notarial act that he was rescinding the contract, and neither had he filed a suit in court to rescind the sale. Finally, it has been ruled that "where time is not of the essence of the agreement, a slight delay on the part of one party in the performance of his obligation is not a sufficient ground for the rescission of the agreement. Considering that in the instant case, private respondent had already actually paid the sum of P12,500.00 of the total stipulated purchase price of P18,000.00 and had tendered payment of the balance of P5,500.00 within the grace period of six months from December 31, 1972, equity and justice mandate that she be given additional period within which to complete payment of the purchase price. AQUILINA P. MARIN V. JUDGE MIDPANTAO L. ADIL G.R. No. L-49018 & L-47986, July 16, 1984 FACTS: Brothers Manuel & Ariston Armada and Aquiline Marin are first cousins. The Armadas in 1963 expected to inherit some lots in General Santos City from their uncle, Proceso Pacificar, who died in 1954. Marin, who resided in Cotabato, had hereditary rights in the estates of her parents, the deceased spouses, Francisco and Monica Provido, of Janiuay Iloilo, who died in 1938 and 1960, respectively. Manuel P. Armada resided in Janiuay. In a document entitled Deed of Exchange with Quitclaim, Marin assigned to the Armada brothers her hereditary share in the testate estate of her deceased mother, Monica Pacificar Vda. de Provido, in Iloilo, in exchange for the land of the Armadas located in Cotabato. The exchange would be rescindible when it is definitely ascertained that the parties have respectively no right to the properties sought to be exchanged. The exchange did not mean that the parties were definitely entitled to the properties being exchanged but it was executed "in anticipation of a declaration of said right". When the deed of exchange was executed, the estate of Proceso Pacificar, in which the Armadas expected to inherit a part, had been adjudicated to Soledad Pronido- Elevencionado a sister of Mrs. Marin and a first cousin also of the Armadas. Soledad claimed to be the sole heir of Proceso. So, the Armadas and the other heirs had to sue Soledad. The protracted litigation ended in a compromise in 1976 when the Armadas were awarded Lots 906-A-2 and 906-A-3, located in Barrio lagao, General Santos City; Marin never possessed these two lots. They were supposed to be exchange for her proindiviso share in her parents' estate in Janiuay. Five years after the deed was executed, Marin agreed to convey to her sister, Aurora Provido-Collado, her interest in 2 lots in January in payment of her obligation amounting to P1,700. Then, in the extra-judicial partition of her parents' estate, Marins share was formally adjudicated to Aurora. It was

stated therein that Marin "has waived, renounced and quitclaimed her share" in favor of Aurora. As already stated, that share was supposed to be exchanged for the two lots in General Santos City which the Armadas received in 1976 after a pestiferous litigation. Hence, the Armadas filed the instant rescissory action against Mrs. Marin. ISSUE: WON THE DEED OF EXCHANGE WAS VALID AND BINDING? HELD: NO. It is evident from the deed of exchange that the intention of the parties relative to the lots, which are the objects of the exchange, cannot be definitely ascertained. We hold that this circumstance renders the exchange void or inexistent (Art. 1378, 2nd par. and Art. 1409[6], Civil Code). It is provided in paragraph 7 that the deed should not be construed as an acknowledgment by the Armadas and Mrs. Marin that they are entitled to the properties involved therein and that it was executed "in anticipation of a declaration of" their rights to the properties. Then, it is stipulated in paragraph 8 that the parties should take possession and make use of the properties involved in the deed. The two provisions are irreconcilable because paragraph contemplates that the properties are still to be awarded or adjudicated to the parties whereas paragraph 8 envisages a situation where the parties have already control and possession thereof. It should be noted that in Marin's answer with affirmative defense she avers therein that her 1968 agreement with her sister means that she would convey her properties to Aurora when the Armadas should be "adjudged to be without rights or interests to any properties in General Santos City." Such a qualifications is not found in her agreement with her sister. The instant rescissory action may be treated as an action to declare void the deed of exchange. The action to declare the inexistence of a contract does not prescribe (Art. 1410, Civil Code). The properties covered by the deed should have been specified and described. A perusal of the deed gives the impression that it involves many properties. In reality, it refers only to 8,124 square meters of land, which the Armadas would inherit from their uncle in General Santos City, and to the 9,000 square meters representing the proindiviso share of Mrs. Marin in her parents' estate. As we have seen, Mrs. Marin rendered impossible the performance of her obligation under the deed. Because of that impossibility, the Armadas could rescind extrajudicially the deed of exchange (Art. 1191 Civil Code). If Mrs. Marin should sue the Armadas, her action would be barred under the rule of exceptio non adimpleti contractus (plaintiff is not entitled to sue because he has not performed his part of the agreement).

3.1.3 MORA / DEFAULT B. BY THE OBLIGEE / CREDITOR

LUISA F. MCLAUGHLIN V. C.A. & RAMON FLORES G.R. No. L-57552 October 10, 1986 FACTS: Petitioner Luisa F. McLaughlin and private respondent Ramon Flores entered into a contract of conditional sale of real property. The deed of conditional sale fixed the total purchase price of P140k payable as follows: a) P26k upon the execution

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS of the deed; and b) the balance of P113k to be paid not later than May 1977. The parties also agreed that the balance shall bear interest at the rate of 1% per month to commence from December 1976, until the full purchase price was paid. In 1979, petitioner filed a complaint for the rescission of the deed of conditional sale due to the failure of private respondent to pay the balance due on May 31, 1977. Later, the parties submitted a Compromise Agreement on the basis of which the court rendered a decision. In said compromise agreement, private respondent acknowledged his indebtedness to petitioner under the deed of conditional sale in the amount of P119k, and the parties agreed that said amount would be payable as follows: a) P50k upon signing of the agreement; and b) the balance of P69k in two equal installments on June 1980 and December 1980. As agreed upon, private respondent paid P50k upon the signing of the agreement and in addition he also paid an "escalation cost" of P25k. Under paragraph 3 of the Compromise Agreement, private respondent agreed to pay P1k monthly rental beginning December 1979 until the obligation is duly paid, for the use of the property subject matter of the deed of conditional sale. Paragraphs 6 and 7 of the Compromise Agreement further state: That the parties are agreed that in the event the defendant (private respondent) fails to comply with his obligations herein provided, the plaintiff (petitioner) will be entitled to the issuance of a writ of execution rescinding the Deed of Conditional Sale of Real Property. In such eventuality, defendant (private respondent) hereby waives his right to appeal to (from) the Order of Rescission and the Writ of Execution which the Court shall render in accordance with the stipulations herein provided for. Xxx That in the event of execution all payments made by defendant (private respondent) will be forfeited in favor of the plaintiff (petitioner) as liquidated damages. In October 1980, petitioner wrote to private respondent demanding that the latter pay the balance of P69k. This demand included not only the installment due on June 1980 but also the installment due on December 1980. Private respondent then sent a letter to petitioner signifying his willingness and intention to pay the full balance of P69k, and at the same time demanding to see the certificate of title of the property and the tax payment receipts. Private respondent holds that on the first working day of said month, he tendered payment to petitioner but this was refused acceptance by petitioner. Petitioner filed a Motion for Writ of Execution alleging that private respondent failed to pay the installment due on June 1980 and that since June 1980 he had failed to pay the monthly rental of P1k. RTC granted the motion for writ of execution. It denied the motion for reconsideration in an order dated November 21, 1980 and issued the writ of execution on November 25, 1980. In an order dated November 27, 1980, the trial court granted petitioner's ex-parte motion for clarification of the order of execution rescinding the deed of conditional sale of real property. ISSUE: WON THE CA ERRED IN DECLARING THE COMPROMISE AGREEMENT RESCINDED? HELD: NO. The general rule is that rescission will not be permitted for a slight or casual breach of the contract, but only for such breaches as are substantial and fundamental as to defeat the object of the parties in making the agreement. In the case at bar, despite Flores' failure to make the payment which was due on June 1980, McLaughlin waived whatever right she had under the

compromise agreement to demand rescission. It is significant to note that on November 17, 1980, or just 17 days after October 31, 1980, the deadline set by McLaughlin, Flores tendered the certified manager's check. Considering that Flores had already paid P101,550.00 under the contract to sell, excluding the monthly rentals paid, certainly it would be the height of inequity to have this amount forfeited in favor McLaughlin. Under the questioned orders, McLaughlin would get back the property and still keep P101,550.00. Moreover, section 4 of Republic Act No. 6552 (Maceda Law) provides as follows: In case where less than two years of installments were paid, the seller shall give the buyer a grace period of not less than sixty days from the date the installment became due. If the buyer fails to pay the installments due at the expiration of the grace period, the seller may cancel the contract after thirty days from receipt by the buyer of the notice of the cancellation or the demand for rescission of the contract by a notarial act. Section 7 of said law provides as follows: Any stipulation in any contract hereafter entered into contrary to the provisions of Sections 3, 4, 5 and 6, shall be null and void. The spirit of these provisions further supports the decision of the appellate court. Assuming that under the terms of said agreement the December 31, 1980 installment was due and payable when on October 15, 1980, petitioner demanded payment of the balance of P69,059.71 on or before October 31, 1980, petitioner could cancel the contract after thirty days from receipt by private respondent of the notice of cancellation. Considering petitioner's motion for execution filed on November 7, 1980 as a notice of cancellation, petitioner could cancel the contract of conditional sale after thirty days from receipt by private respondent of said motion. The tender made by private respondent of a certified bank manager's check payable to petitioner was a valid tender of payment. Moreover, Section 49, Rule 130 of the Revised Rules of Court provides that: An offer in writing to pay a particular sum of money or to deliver a written instrument or specific property is, if rejected, equivalent to the actual production and tender of the money, instrument, or property. However, although private respondent had made a valid tender of payment which preserved his rights as a vendee in the contract of conditional sale of real property, he did not follow it with a consignation or deposit of the sum due with the court. In one case, it was held: True that consignation of the redemption price is not necessary in order that the vendor may compel the vendee to allow the repurchase within the time provided by law or by contract. We have held that in such cases a mere tender of payment is enough, if made on time, as a basis for action against the vendee to compel him to resell. But that tender does not in itself relieve the vendor from his obligation to pay the price when redemption is allowed by the court. In other words, tender of payment is sufficient to compel redemption but is not in itself a payment that relieves the vendor from his liability to pay the redemption price." In compliance with a resolution issued by the lower court, both parties submitted their respective manifestations which confirm that the Manager's Check in question was subsequently withdrawn and replaced by cash, but the cash was not deposited with the court. According to Article 1256 of the Civil Code of the Philippines, if the creditor to whom tender of payment has been made refuses without just cause to accept it, the debtor shall be released from responsibility by the consignation of the thing or sum due, and that

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS consignation alone shall produce the same effect in the five cases enumerated therein; Article 1257 provides that in order that the consignation of the thing (or sum) due may release the obligor, it must first be announced to the persons interested in the fulfillment of the obligation; and Article 1258 provides that consignation shall be made by depositing the thing (or sum) due at the disposal of the judicial authority and that the interested parties shall also be notified thereof. Tender of payment must be distinguished from consignation. Tender is the antecedent of consignation, that is, an act preparatory to the consignation, which is the principal, and from which are derived the immediate consequences which the debtor desires or seeks to obtain. Tender of payment may be extrajudicial, while consignation is necessarily judicial, and the priority of the first is the attempt to make a private settlement before proceeding to the solemnities of consignation. In the case at bar, although as above stated private respondent had preserved his rights as a vendee in the contract of conditional sale of real property by a timely valid tender of payment of the balance of his obligation which was not accepted by petitioner, he remains liable for the payment of his obligation because of his failure to deposit the amount due with the court.

to pay Atty. Moya as additional compensation for his services only in the amount of P50k subject to the condition that same shall be paid after the case is terminated in their favor and/or the property involved is sold; and (3) That defendants shall compensate Atty. Moya said amount in addition to what they have paid before. The trial court issued an Order directing the spouses to pay Atty. Moya the sum of P100,000.00 as and by way of attorneys fees. ISSUE: WON THE P100K AWARD ATTORNEYS FEES WAS PROPER? HELD: NO. The reasonableness of the amount of attorneys fees awarded to private respondent should be properly gauged on the basis of the long-standing rule of quantum meruit, meaning, as much as he deserves. Where a lawyer is employed without agreement as to the amount to be paid for his services, the courts shall fix the amount on quantum meruit basis. In such a case, he would be entitled to receive what he merits for his services. In this respect, Section 24, Rule 138 of the Rules of Court provides: Sec. 24. Compensation of attorneys, agreement as to fees. - An attorney shall be entitled to have and recover from his client no more than a reasonable compensation for his services, with a view to the importance of the subject matter of the controversy, the extent of the services rendered, and the professional standing of the attorney. x x x In addition, the following circumstances, codified in Rule 20.1, Canon 20 of the Code of Professional Responsibility, serves as a guideline in fixing a reasonable compensation for services rendered by a lawyer on the basis of quantum meruit: a) The time spent and the extent of the services rendered or required; b) The novelty and difficulty of the questions involved; c) The importance of the subject matter; d) The skill demanded; e) The probability of losing other employment as a result of acceptance of the proffered case; f) The customary charges for similar services and the schedule of fees of the IBP chapter to which he belongs; g) The amount involved in the controversy and the benefits resulting to the client from the services; h) The contingency or certainty of compensation; i) The character of the employment, whether occasional or established; and j) The professional standing of the lawyer. In the present case, aside from invoking his professional standing, private respondent claims that he was the one responsible in forging the initial compromise agreement wherein FSMDC agreed to pay P2.7M. The fact remains, however, that such agreement was not consummated because the checks given by FSMDC were all dishonored. It was not the private respondent who was responsible in bringing into fruition the subsequent compromise agreement between petitioners and FSMDC. Nonetheless, it is undisputed that private respondent has rendered services as counsel for the petitioners. He prepared petitioners Answer and Pre- Trial Brief, appeared at the Pre-Trial Conference,

3.1.3 BY MORA / DEFAULT C. COMPENSATIO MORAE

ELNORA R. CORTES V. C.A. & F. S. MGT AND DEVT CORP. [G.R. No. 121772. January 13, 2003] FACTS: The controversy stemmed from a civil case for specific performance with damages filed by F.S. Management and Development Corporation (FSMDC) against spouses Edmundo and Elnora Cortes involving the sale of the parcel of land owned by the said spouses. Spouses Cortes retained the professional services of Atty. Felix Moya. However, they did not agree on the amount of compensation for the services to be rendered by Atty. Moya. Before a full-blown trial could be had, defendants spouses Cortes and plaintiff FSMDC decided to enter into a compromise agreement. Defendants spouses received from plaintiff FSMDC, three checks totaling P2.7M. Thereafter, Atty. Moya filed an Urgent Motion to Fix Attorneys Fees, Etc. praying that he be paid a sum equivalent to 35% of the amount received by the defendants spouses which the latter opposed contending that the amount Atty. Moya seeks to recover is utterly excessive and is not commensurate to the nature, extent and quality of the services he had rendered. Later, the Cortes spouses and Atty. Moya settled their differences by agreeing in open court that the former will pay the latter the amount of P100k as his attorneys fees. About six months after the compromise, Atty. Moya filed an Ex-Parte Manifestation praying that his Motion to Fix Attorneys Fees be resolved on the basis of the agreement of the parties in chambers. The Cortes spouses filed their Comment claiming: (1) That they agreed to the settlement of P100,000k attorneys fees expecting that the checks paid by FSMDC will be good but it turned out that they were all dishonored, and no compromise agreement was pushed through; (2) That defendants are willing

CIV LAW REVIEW - OBLICON DIGESTS attended a hearing held on July 13, 1990, cross-examined the witness of FSMDC, and was present in the conference at the Manila Hotel between the parties and their respective counsels. All these services were rendered in the years 1990 and 1991 where the value of a peso is higher. Thus, we find the sum of P100,000.00 awarded to private respondent as his attorneys fees to be disproportionate to the services rendered by him to petitioners.The amount of P50,000.00 as compensation for the services rendered by Atty. Moya is just and reasonable. Besides, the imposition of legal interest on the amount payable to private respondent is unwarranted. Article 2209 of the Civil Code invoked by Atty. Moya and cited by the appellate court, finds no application in the present case. It is a provision of law governing ordinary obligations and contracts. Contracts for attorneys services in this jurisdiction stand upon an entirely different footing from contracts for the payment of compensation for any other services. We have held that lawyering is not a moneymaking venture and lawyers are not merchants. Thus, a lawyers compensation for professional services rendered are subject to the supervision of the court, not just to guarantee that the fees he charges and receives remain reasonable and commensurate with the services rendered, but also to maintain the dignity and integrity of the legal profession to which he belongs. SPOUSES WILLIAM AND JEANETTE YAO V. CARLOMAGNO B. MATELA, [G.R. NO. 167767 & 167799, AUGUST 29, 2006] FACTS: Spouses Yao contracted the services of Matela, a licensed architect, to manage and supervise the construction of a two-unit townhouse at a total cost of P5M. The construction started in the first week of April 1997 and was completed in April 1998, with additional works costing P300K. Matela alleged that the spouses Yao paid him the amount of P4.6M, thereby leaving a balance of P741k. When his demand for payment went unheeded, Matela filed a complaint for sum of money with the RTC. In their answer, the spouses Yao denied that the project was completed in April 1998. Instead, they alleged that Matela abandoned the project without notice. They claimed that they paid Matela the sum of P4.7M which should be considered as sufficient payment considering that Matela used sub-standard materials causing damage to the project which needed a substantial amount of money to repair. RTC rendered judgment in favor of Matela, based on documents issued by the Building Official of Makati City. The Court of Appeals affirmed the decision of the lower court but modified the amount of actual damages to P391k. Thereafter, another case was filed by Matela, regarding the collection of the P300k additional construction cost. ISSUE: WON MATELA MAY COLLECT ACTUAL DAMAGES AND THE ADDITIONAL CONSTRUCTION COST? HELD: NO, BOTH PARTIES ARE GUILTY OF BREACH. Reciprocal obligations are those which are created or established at the same time, out of the same cause, and which result in mutual relationships of creditor and debtor between the parties. These obligations are conditional in the sense that the fulfillment of an obligation by one party depends upon the fulfillment of the obligation by the other. In reciprocal obligations, the general rule is that fulfillment by both parties should be simultaneous or at the same time.