Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robinson V. Graves

Uploaded by

brownshugaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robinson V. Graves

Uploaded by

brownshugaCopyright:

Available Formats

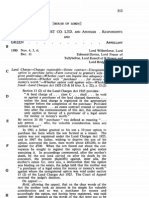

1 ROBINSON v. GRAVES [1932. R. 2021.

] Contract - Commission to paint Portrait - Sate of Goods - Work and Labour - Sale of Goods Act, 1893 (56 & 57 Vict. c. 71), s. 4. The defendant orally commissioned the plaintiff, an artist, to paint the portrait of a lady and promised to pay 250 guineas therefor. The defendant subsequently repudiated the contract before the portrait was completed. In an action by the plaintiff. for the agreed price of the portrait: Held, that it was a contract for work and labour and not for the sale of goods, as the substance of the contract was that skill and labour should be exercised upon the production of the portrait, and that it was only ancillary to that contract that there would pass from the artist to his customer some materialsnamely, the paint and the canvas, in addition to the skill and labour involved in the production of the portrait, and that therefore the plaintiff could recover notwithstanding that there was no note or memorandum in writing of the contract. Clay v. Yates (1856) I H. & N. 73; 25 L. J. (Ex.) 237 and Lee v. Griffin (1861) I B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252 considered. Dictum of Blackburn J. in Lee v. Griffin I B. & S. 278; 3o L. (Q. B.) 254 doubted. APPEAL from a decision of Acton J. The plaintiff, William Howard Robinson, who was a portrait painter, claimed to recover from the defendant, Frederick Beresford Johnston Graves, the sum of 262l. 10s. as being the agreed fee for a portrait commission given by the defendant to the plaintiff. The plaintiff alleged that by a contract made verbally on July 27, 1932, the defendant commissioned the plaintiff to paint, and agreed to pay for, a three-quarter length portrait of a lady, who had since become the defendant's wife, for the sum of 250 guineas, one-half of which was to be paid in advance, subsequently reduced to 100 guineas paid in advance. The plaintiff commenced to paint the portrait, the lady giving him a sitting for that purpose, but the defendant on August 2, 1932, wholly repudiated and put an end to the contract. The defendant by his defence denied that he had given a commission to the plaintiff to paint the portrait or had agreed to pay the plaintiff 250 guineas therefor. He also relied upon the provisions of s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893. 1 Acton J. accepted the evidence of the plaintiff and held that a contract for the painting of the portrait had been made, but that according to the decision in Lee v. Griffin2 it was an agreement for the sale of goods of the value of more than 10l., of which contract there was no note or memorandum in writing, and that therefore it came within s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893, and was not enforceable by action. The plaintiff appealed. Sylvain Mayer K.C. and John Fennell for the appellant. This was not a sale of goods within s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893, and therefore there was no necessity for a note or memorandum in writing of the contract. The contract was one for work and labour. If work and labour constitute the essence of the contract that is decisive that the contract is not one for the sale of goods. This is particularly true in the case of a work of art. In Addison on Contracts, 11th ed., p. 867, it is stated that "In the case of works of art the work and skill of the workman constitute, in general, the essence of the contract, the materials being merely accessorial; and, whenever the skill and labour are of the highest description, and the materials of small comparative value, the contract is a contract for work, labour and

2 materials, and not a contract of sale." The effect of the cases is stated in Benjamin on Sale, 7th ed., p. 177, as follows: "The principles already discussed have shewn that a contract of sale is not constituted merely by reason that the property in materials is to be transferred to the employer. If they are simply accessory to work and labour, the contract is for work, labour, and materials." In Clay v. Yates 3 the contract was that the C. A. Plaintiff, a printer, should print for the defendant a second 1935 edition of his book, the plaintiff to find the material including the paper, and it was held that it was a contract to do work and labour, and not a contract for the sale of a thing. Pollock C.B. said 4: " It seems to me the true rule is this, whether the work and labour is of the essence of the contract, or whether it is the materials that are found. My impression is, that in the case of a work of art, whether it be silver or gold, or marble, or common plaster, that is a case of the application of labour of the highest description, and the material is of no sort of importance as compared with the labour; and therefore that all this would be recoverable as work and labour and materials found." Martin B., in the course of the argument, said 5: " Suppose an artist paints a Portrait for 300 guineas, and supplies the canvas for it, which is worth 10s., surely he might recover under a count for work and labour." The decision of Mathew J. in Isaacs v. Hardy 6, where he held that a contract by an artist with a picture dealer to paint a picture of a given subject at an agreed price was a contract for the sale of a chattel, is not helpful. No reasons are there given, and the action was by the picture dealer against the artist who was to bring the picture into existence. The contract was for something after work and labour had been done. In Grafton v. Armitage7, Erle J. said in the course of the argument: " Suppose an attorney were employed to prepare a partnership or other deed: the draft would be upon his own paper, and made with his own pen and ink; might he not maintain an action for work and labour in preparing it ? " Lee v. Griffin 8, which is relied upon by the other side, is not a decision which is really against the present contention. It was there held that a 'Contract to make a set of artificial teeth was a contract for the sale of a chattel and therefore within s. 17 of the Statute of Frauds. In that case Crompton J. said 9: " It may be the cause of action is for work and labour, when the Materials supplied are merely ancillary, as in the case put of an attorney or printer." The remarks of Blackburn J.10 in that case went further than were necessary for the decision of that case and are not binding. Under s. 5, sub-s. i (a), of the Copyright Act, 1911, the copyright in a portrait is in the person by whom such portrait was ordered. Sylvester Gates and Norman F. Stogdon for the respondent. The true test between a contract for sale of goods and a contract for work and labour is that laid down by Blackburn J. in Lee v. Griffin11, where he said12: " If the contract be such that it will result in the sale of a chattel, the proper form of action, if the employer refuses to accept the article when made, would be for not accepting. But if the work and labour be bestowed in such a manner as that the result would not be anything which could properly be said to be the subject of sale, then an action for work and labour is the proper remedy." Later he said: " I do not think that the relative value of the labour and of the materials on which it is bestowed can in any case be the test of what is the cause of action; and that if Benvenuto Cellini had contracted to execute a work of art for another, much as the value of the skill might exceed that of the materials, the contract would have been the less for the sale of a chattel." The test that as laid down by Blackburn J. in 1861 has stood unchallenged till to-day. It has been cited and approved in several cases. Mathew J. held in Isaacs v. Hardy13 that a contract by an artist to paint a picture at an agreed price was a contract for the sale of a chattel. That is a clear authority in the present case. Lord Reading C.J. in Rex v. Wood Green Profiteering Committee14 said: " The cases of Lee v. Griffin15 andIsaacs v. Hardy16 shew that to determine whether or not there has been the sale of an article the value of the labour, as compared with that of the materials, cannot be taken into account." In Benjamin on Sale, 7th ed., p.172, the rule is stated thus; If the contract is intended to result in transferring for a price from B. to A. a chattel in which A. had no previous property, it is a contract for the sale of a chattel." In an article on s.17 of the Statute of Frauds in the Law Quarterly Review for January, 1885 (PP. I, 9), written by the late Mr. Justice Stephen and Sir Frederick Pollock, a

3 contract for the sale of goods is defined as "a contract by which the vendor promises to transfer to the purchaser, and by which the purchaser promises to accept from the vendor, a transfer of property in goods, whether the goods are delivered at the time of the contract or are intended to be delivered at some future time, and whether the goods are, at the time of the contract, actually made, procured. or provided, or fit or ready for delivery or not, and whether or not any act is requisite for making or delivering or rendering them fit for delivery." One of the illustrations given is: " A promises to paint a picture of great value for B, A finding the paint and canvas, which are of small value, and B promising to pay for the whole as a work of art. This is a contract for the sale of goods." The test laid down by Pollock C.B. in Clay v. Yates 17 is not binding to-day. All the judges in Lee v. Griffin 18 agreed with the test that if the contract be such that a chattel is ultimately to be delivered by the plaintiff to the defendant, the cause of action is goods sold and delivered. GREER L.J. We need not trouble you, Mr. Sylvain Mayer. This appeal raises a very interesting question, which has been well argued and is not free from difficulty, having regard to the fact that there has not yet been any actual decision on the point involved in this case, though there have been in some of the cases dicta tending in one direction and in others dicta tending in the other direction. The question to be decided is this: Whether when a person goes to an artist to have a portrait painted, it may be his own portrait or the portrait of some friend (as for instance his wife), and the commission is accepted by the artist, they are making a bargain for the manufacture of future goods to be delivered when those goods come into existence in circumstances which make it a sale of goods within the meaning of s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893, which has now taken the place of s. 17 of the Statute of Frauds relating to the sale of goods. I propose to look at the question first without dealing with the authorities, because after all we are dealing with the meaning of the English language in the statute and its application to particular facts. I can imagine that nothing would be more surprising to a client going to a portrait painter to have his portrait painted and to the artist who was accepting the commission than to be told that they were making a bargain about the sale of goods. It is, of course, possible that a picture may be ordered in such circumstances as will make it an order for goods to be supplied in the future, but it does not follow that that is the inference to be drawn in every case as between the client and the artist. Looking at the propositions involved from the point of view of interpreting the words in the English language it seems to me that the painting of a portrait. In these circumstances would not, in the ordinary use of the English language, be deemed to be the purchase and sale of that which is produced by the artist. It would, on the contrary, be held to be an undertaking by the artist to exercise such skill as he was possessed of in order to produce for reward a thing which would ultimately have to be accepted by the client. If that is so, the contract in case was not a contract for the sale of goods within the meaning of s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893. There are only two cases to which I think it is necessary to refer. The first case is Clay v. Yates.19 That was concerned with the question whether a 'contract" with a printer to print and deliver a book to a customer who desired print and deliver a book to a custom" to have it printed was or was not a sale of goods. In the course of the argument Martin B. said this 20 " Suppose an artist paints a portrait for 300 guineas, and supplies the canvas for it, which is worth 10s., surely he might recover under a count for work and labour." I regard that as an expression of opinion by a high authority on all questions of the common law that in those circumstances there would not be any sale of goods, but there would be a contract for work and labour; and in the judgments which follow the learned judges seem to me to agree with that view, because Pollock C. B. uses these words 21: " My impression is, that in the case of a work of art, whether in gold, silver, marble or plaster, where the application of skill and labour is of the highest description, and the material is of no importance as compared with the labour, the price may be recovered as work, labour and materials." Alderson B. agreed with that judgment and did not find it necessary to add anything, and then Martin B. says 22: " I am of the same opinion. There are three matters of charge well known to the law, viz., for

4 labour simply, for labour and materials, and for goods sold and delivered. Now every case must be judged of by itself, and what is the present case ? " Then he deals with that case and agrees with the judgment that had been delivered by the Chief Baron. Bramwell B. says 23 : " I did not hear the whole of the argument, and will not therefore give a decided opinion, but I am inclined to think the plaintiff is entitled to recover, even assuming Mr. Quain's argument to be right. The contract is to print a treatise at a dedication, the latter to be thereafter furnished. That imposed on the defendant the obligation of furnishing a dedication, such as the plaintiff could by law print." A contract to make a portrait or produce a portrait involves the fact that the person whose portrait is to be painted should contribute something, that is to say he should contribute the sittings which are necessary for the purpose of enabling the portrait to be painted. Now it is said that that case is inconsistent with the subsequent case of Lee v. Griffin. 24 So far as the facts of that case are concerned it affords no help to the decision of the present case, because it was concerned with the question whether, when a dentist undertakes to make a plate of false teeth-more frequently called a denture-that is or is not a sale of goods. In that case the principal part of that which the parties are dealing with is the chattel which will come into existence when such skill as may be necessary to produce it has been applied by the dentist and those who work for him; but in the course of delivering the judgments in that case Crompton J. and Hill J. said nothing whatever which would throw any doubt upon the views expressed in the earlier case of Clay v. Yates. 25 Crompton J. says26: " However, on the point which was made at the trial, whether the plaintiff could not succeed on the count for work labour, and materials, I am also clearly of opinion against the plaintiff. Whether the cause of action be work and labour, or goods sold and delivered, depends on the particular nature of each individual contract "; and then he refers to the case of Clay v. Yates 27 as turning upon the peculiar circumstances of the case, and concludes with these words: " I do not agree with the proposition, that whenever skill is to be exercised in carrying out the contract, that fact makes it a contract for work and labour, and not for the sale of a chattel; it may be the cause of action is for work and labour, when the materials supplied are merely ancillary, as in the case put of an attorney or printer. But in the present case the goods to be furnished, viz., the teeth, are the principal subject-matter; and the case is nearer that of a tailor, who measures for a garment and afterwards supplies the article fitted." In giving judgment Hill J. says this 28: " The proposition of Bayley J., that where a person has bestowed work and labour on his own materials he cannot maintain an action for work and labour, is certainly not universally true; and Tindal C.J., as well as the other members of the Court, in Grafton, v. Armitage, 29 repudiated that doctrine, and explained that Bayley J. must be regarded as speaking with reference to the particular circumstances of the case then before this Court; and the same view was taken by the Court of Exchequer inClay v. Yates " 30, the case to which I have already referred. It is quite true that in giving judgment Blackburn J. (to whose views on any question of contract or of common law the greatest weight is to be attached) uses these words 31: " The other question is, whether the present was a contract for the sale of goods, or for work and labour. In order to ascertain this you must of course, in each case, look at the contract itself. If the contract be such that if will result in the sale of a chattel, the proper form of action, if the employer refuses to accept the article when made, would be for not accepting." Lower down in his judgment he says: "An attorney employed to draw a deed is a familiar instance of the latter proposition" -that is to say where the action is for work and labour- "and it would be an abuse of language to say that the paper or parchment of the deed were goods sold and delivered." Then he quotes Tindal C.J. in Grafton v. Armitage 32, observing of Atkinson v. Bell 33 : " The substance of the contract was, goods to be sold and delivered by the one party to the other." I treat that judgment as indicating that in the view of Blackburn J. one has to look to the substance of the contract. If you find, as they did in Lee v. Griffin 34, that the substance of the contract was the production of something to be sold by the dentist to the dentist's customer, then that is a sale of goods. But if the substance of the contract, on the other hand, is that skill and labour have to be exercised for the production of the article and that it is only ancillary to that that

5 there will pass from the artist to his client or customer some materials in addition to the skill involved in the production of the portrait, that does not make any difference to the result, because the substance of the contract is the skill and experience of the artist in producing the picture. For these reasons I am of opinion that in this case the substance of the matter was an agreement for the exercise of skill and it was only incidental that some materials would have to pass from the artist to the gentleman who commissioned the portrait. For these reasons I think that this was not a contract for the sale of goods within the meaning of s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893, but it was a contract for work and labour and materials. That disposes of the subject-matter of this appeal with this exception, that it does not follow that the plaintiff is entitled, as damages, to the full amount that he would have recovered if he had been allowed to complete the contract, because there would have to be some expenditure by the artist upon the cost of the canvas and the coats of paint to be put upon the canvas, and that ought to be deducted for that as well as for release of the artist's time for other work. As no such question was raised or discussed at the trial we think that in the circumstances it is open to this Court to say that something ought to be deducted, and the damages, therefore, should be, not the 250l. claimed, but, say, 200l. We have to make a guess, and this is rather on the generous side towards the artist, but the only alternative would be to send the case back for a new trial, a course which, as I understand the argument, neither party is desirous should be taken. For these reasons I think there ought to be judgment for the plaintiff for 200l. damages. SLESSER L. J. I am of the same opinion. In this case the plaintiff is unable to produce any document in writing sufficient evidentially to maintain his contract which has been found to have been made, orally, with the defendant. If this be a contract for work and labour done that does not hurt him. If it be a contract for the sale of goods or an agreement to deliver goods under a sale, then the objection has been held to be fatal to him. In my opinion this is a contract for work and labour. The question whether such a contract is for sale of goods or for work and labour done which ultimately may produce a chattel which is delivered to the purchaser has vexed jurists from the earliest ages. According to the Civil Law as finally settled by Justinian, the test whether a contract was locatio conductio operis or emptio venditio depended upon whether the material was supplied by the employer or by the workman. That view appears to have been accepted by Bayley J. in the case of Atkinson v. Bell 35, but since that time the dictum of Bayley J. has been repudiated in all the authorities. It was repudiated in Grafton v. Armitage36 by Maule J. and Erle J. and has not since been followed. The English doctrine is far more elastic in this matter than that contained in the Institutes of Justinian or in most of the foreign Civil Codes. The question of the ownership of the material on which the work is done is not conclusive of the matter. Now an other test which has been suggested is that which appears particularly prominently in the judgment of Blackburn J. (as he then was) in the case of Lee v. Griffin.37 There Blackburn J. says this; "I do not think that the test to apply to these cases is whether the value of the work exceeds that of the materials used in its execution; for, if a sculptor were employed to execute a work of art, greatly as his skill and labour, supposing it to be of the highest description, might exceed the value of the marble on which he worked, the contract would, in my opinion, nevertheless be a contract for the sale of a chattel." It is that observation of that very learned judge which has given me considerable doubt and difficulty in this case, but I have come to the conclusion, looking at the authorities as a whole, and considering the matter as one of principle myself, that if Blackburn J. there meant to state that whenever there was an agreement whereby a chattel would ultimately have to be delivered there was of necessity a sale of the chattel, he is stating the matter too broadly. As

6 is indicated by the old plea in Bullen & Leake for a common indebitatus account for work done, what is claimed is "money payable by the defendant to the plaintiff for work done and materials provided by the plaintiff for the defendant at his request" ; and normally, in the class of case which we have here to consider, when the work has to be done in order to make the chattel fit for ultimate delivery to the purchaser, there will always be, or nearly always be, some material which at some stage or another will have to be delivered, and if that be the only test, so that the ultimate delivery of some material decides that the subjectmatter is the sale of goods, I would find it difficult to understand how such cases as the delivery of written documents of parchment by a solicitor, whichhave always been agreed to be questions of work and labour and not sale of goods, would not fall within thecategory of sale of goods. But I think that the authorities are clear to the contrary, notwithstanding the weighty observations of Blackburn J. In the first of the two cases to which my Lord drew attention (to which, therefore, I need not refer in any detail), namely, the case of Clay v. Yates38, Pollock C.B. says39 : " The true rule is this, whether the work and labour is of the essence of the contract, or whether it is the materials that are found." Then he gives the illustration of a work of art: " Whether it be silver or gold, or marble, or common plaster, that is a case of the application of labour of the highest description, and the material is of no sort of importance as compared with the labour ; and therefore that all this would be recoverable as work and labour and materials found." Martin B. speaks to the same effect, and he says40 : " I do not think it is profitable to go into an inquiry of the other cases, for in the common sense and understanding of mankind, this is clearly a case of work and labour and materials." In Lee v. Griffin41, the later case, Crompton J. seems to me to support that view. He says 42 : " I do not agree with the proposition, that whenever skill is to be exercised in carrying out the contract, that fact makes, it a contract for work and labour, and not for the sale of a chattel ; it may be the cause of action is for work and labour, when the materials supplied are merely ancillary, as in the case put of an attorney or printer" to which I might add, a painter. Hill J. speaks of it being a sale of goods when the substance of the contract is goods to be sold and delivered, and therefore inferentially suggests that where it is not the substance of the contract but merely ancillary it may be a contract for work and labour; so that all these authorities seem to me to be consistent. There is one other matter which I would comment upon. It has been pointed out in this case, and is the fact. that under the Copyright Act, 1911, s. 5, sub-s. I, it is provided that "the author of a work shall be the first owner of the copyright therein; Provided that (a) where, in the case of [a] . . . . portrait the . . . . original was ordered by some other person . . . . then, in the absence of any agreement to the contrary, the person by whom such . . . . original was ordered shall be the first owner of the copyright," and therefore there would be in such a case as this a restriction upon the proprietary rights of the painter to dispose of these goods which one would not have expected to find if the property in the goods was still in an unrestricted state in his disposition before he delivered them under the contract of sale of goods to the purchaser. One of the learned judges in an earlier case points out that in that particular case. where it was held that the contract was one for work and labour, there was a restriction on the power of the printer to dispose of the goods. For these reasons I am of opinion that on the facts of this case it is here shown that the material, the paint and the canvas, were merely ancillary to the actual technical work of producing the work of art and that therefore this is a contract for work and labour. I will guard myself, however, by saying that I only decide this case upon its own particular facts. There may be cases where portraits are ordered in circumstances which would constitute the contract one for the sale of a picture as a chattel. In the circumstances of this case, however, where the portrait of a specific lady was ordered to be painted, and where, I think, the defendant who gave the commission impliedly contracted that the lady should give sittings in

7 order that the work might be executed, I think it is impossible to say that the mere ultimate delivery of the picture would constitute a sale of goods. Consequently s. 4 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1893, affords no protection to the defendant in this case, and this appeal must be allowed. ROCHE, L.J. The defendant in this action desired that a portrait should be painted of a lady who subsequently became his wife. He, as the learned judge found, entered into a contract with the plaintiff, an artist, for the painting of the lady's portrait. The portrait was not painted because the defendant refused to go on with the contract. The artist, the plaintiff, sued the defendant for the price of the portrait or for damages. At the trial the defendant disputed the making of a contract. The judge found the facts in that matter entirely in favour of the plaintiff, and held that the contract alleged by the plaintiff was established. The learned judge, however, felt himself bound by the case of Lee v. Griffin 43 to hold that the contract between the parties was a contract of sale and not a contract for work and labour. In so doing the learned judge was, I think, too much influenced by an expression in Blackburn J.'s judgment 44 in that case in reference to a well known goldsmith artist of Renaissance Italy. With the greatest possible respect to the opinion of Blackburn J. I doubt if he was historically correct in regarding Benvenuto Cellini as a seller of his works of art. If I am not mistaken he generally worked for his noble patrons for a fee or for a salary on materials which they provided. But however that may be, the learned judge's conclusion that he was bound by Lee v. Griffin 45 to decide in favour of the defendant was, I think, a mistaken view. On the contrary I think that Lee v. Griffin 46 is an authority for a decision in favour of the plaintiff. In Lee v. Griffin 47 the authority of Clay v. Yates 48, which clearly is a decision in favour of the plaintiff, was recognized, and in Lee v. Griffin 49 Blackburn J., whose has been principally relied on as an authority for the defendant, said this 50: " If the work and labour be bestowed in such a manner as that the result would not be anything which could properly be said to be the subject of sale, then an action for work and labour is the proper remedy. An attorney employed to draw a deed is a familiar instance of the latter proposition; and it would be an abuse of language to say that the paper or parchment of the deed were goods sold and delivered." Equally, in my judgment, if the history and reality of the transaction involved in the painting of a portrait of this kind is considered, it would be an abuse of language to say that the portrait is sold. In former days the phrase used would have been: "What painter are you going to employ to paint the portrait ?" In these days the phrase is: "Who is commissioned to paint the portrait ?" Both phrases alike are representative of a transaction which is a mandate or authority given to another for reward to execute a certain thing which you desire-namely, the production of a portrait or representation of yourself or some one whom you wish to be so represented. That was the language, I think, employed in this case. The evidence as reported was that the defendant asked the plaintiff his fee for a portrait of Miss Finnegan, and then later the plaintiff was commissioned to carry out the work. In those circumstances, adopting the test put Blackburn J. in Lee v. Griffin 51, I have no doubt that the proper conclusion to be drawn is that this was a contract not for the sale of goods but for the employment of an artist to do work which the defendant desired that he should do. The matter mentioned by Slesser L. J. as to the Copyright Act, 1911, tends, of course, in the same direction, because it is plain by reason of the Act, and I think also by reason of the nature of the contract between the parties, that it would be quite impossible and would amount to breach of contract if the plaintiff, when he had begun to paint this portrait, had left off and sold the portrait to somebody else. In no respect at all was it a transaction of which the end was the delivery of goods, but it was rather a transaction such as I have attempted to describe. For these reasons I agree that the appeal should be allowed and that judgment should be entered for the plaintiff for the sum of 200l. that in deciding as we have done we are not deciding anything which is necessarily contrary to the decision of Mathew J. in the shortly reported case of Isaacs v. Hardy. 52, which dealt with a contract of a very different kindnamely, where a picture dealer, whose sole object was to acquire something which he might

8 sell in his business, engaged an artist to paint and deliver to him a picture of a given subject at an agreed price. It must not be taken that we are in any way overruling that case or deciding whether it was right or wrong. Appeal allowed. Judgment for Plaintiff for 200l. Leave to appeal refused. Solicitors for appellant : Halliday, Clark & Co. Solicitors for respondent : Whitelock & Storr. R. F. S. ENDNOTES: 1. [(1) Sale of Goods Act, 1893, S. 4, sub-s. I : "A contract for the sale of any goods of the value of ten pounds or upwards shall not be enforceable by action unless the buyer shall accept part of the goods so sold. and actually receive the same, or give something in earnest to bind the contract or in part payment, or unless some note or memorandum in writing of the contract be made and signed by the party to be charged or his agent in that behalf." 2. I B. & S. .272 ; 3o L.J. (Q.B.) 252. 3. I H. & N. 73 ; 25 L. J. (EX.) 237 4. 25 L. J. (Ex.) 239. 5. 1 H. & N. 76. 6. (1884) Cab. & E. 287. 7. (1845) 2 C. B. 336, 339; 15 L. J. (C. P.) 20, 21. 8. 1 B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q.B.) 252. 9. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 253; 1 B. & S. 275. 10. 30 L. J. (Q.B.) 254; I B. & S. 278. 11. 1 B. & S. 272, 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 12. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 254 (4) 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 254 [For the verbally different text of the authorized report see P. 589, post.] 13. Cab. & E. 287. 14. (1919) 89 L. J. (K. B.) 55. 15. Ibid. n. 11 16. Ibid. n. 13 17. I H. & N. 73, 78; 25 L. J. (Ex.) 237, 239. 18. B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q.B.) 252. 19. I H. & N. 73; 25 L. J. (EX.) 237. 20. 1 H. & N. 76. 21. Ibid. 78. 22. I H. & N. 79. 23. Ibid. 80. 24. B. & S. 272; 3o L. J.(Q.B.) 252 25. 1 H. & N. 73: 25 L. J (Ex.) 237 26. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 253. 27. Ibid. n. 23 28. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 253. 29. 2 C. B. 336;i_5 L. J. (C. P.) 20. 30. 1 H. & N. 73 ; 25 L. J. (Ex.) 237. 31. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 254. 32. 2 C. B. 336; 15 L. J. (C. P.) 20 33. (1828) 8 B. & C. 277. 34. 1 B. & S. 272; 30 L.J. (Q. B.) 252.

9 35. 8 B. & C. 277, 283. 36. 2 C. B. 336; 15 L. J. (C. P.) 20. 37. 1 B. & S. 272, 278. 38. I H. & N. 73 ; 25L.J. (Ex.) 237 39. 25 L. J. (Ex.) 239. 40. Ibid. 240. 41. 1 B. & S. 272 ; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 42. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 253. 43. 1 B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 44. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 254. 45. 1 B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 46. 1 B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 47. 1 B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 48. 1 H. & N. 73; 25 L. J. (Ex.) 237. 49. 1 B. & S. 272; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 252. 50. 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 254. 51. I B. & S. 277 ; 3o L. J. (Q. B.) 254. 52. Cab. & E. 287.

You might also like

- Sale of Goods - ProjectDocument8 pagesSale of Goods - ProjectRohit Vijaya ChandraNo ratings yet

- Revision Notes CapacityDocument7 pagesRevision Notes CapacityJudith KendallNo ratings yet

- Sale of Goods Lecture Guide Notes 2021.Document55 pagesSale of Goods Lecture Guide Notes 2021.Nyapendi Rose maryNo ratings yet

- In Re New British Iron Company, (1898) 1 Ch. 324Document9 pagesIn Re New British Iron Company, (1898) 1 Ch. 324Jikku Seban GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Council House Contract DisputeDocument8 pagesCouncil House Contract DisputeYee Sook YingNo ratings yet

- Premchand Nanthu V The Land Officer 1960 Ea 941 (CA Decision)Document20 pagesPremchand Nanthu V The Land Officer 1960 Ea 941 (CA Decision)herman gervasNo ratings yet

- AS-3014 B.A. LL.B. (First Semester) Examination, 2013 Law of Contract-IDocument3 pagesAS-3014 B.A. LL.B. (First Semester) Examination, 2013 Law of Contract-Iudupiganesh3069No ratings yet

- CONtractsDocument8 pagesCONtractsmanjeet kumarNo ratings yet

- R v. Kirikiri, (1982) 2 NZLR 648Document4 pagesR v. Kirikiri, (1982) 2 NZLR 64813No ratings yet

- Firm C7 Workshop One (Banking)Document22 pagesFirm C7 Workshop One (Banking)MUBANGIZI ABBYNo ratings yet

- The University of Zambia School of Law: Name:Tanaka MaukaDocument12 pagesThe University of Zambia School of Law: Name:Tanaka MaukaTanaka MaukaNo ratings yet

- The CIF Contract: ContractsDocument4 pagesThe CIF Contract: ContractsNurul Shuhada SuhaimiNo ratings yet

- HYDE V WRENCH (1840) 3 Beav-1Document2 pagesHYDE V WRENCH (1840) 3 Beav-1Karen MalsNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ContinuationDocument15 pagesLabour Law Continuationيونوس إبرحيم100% (1)

- Cases On Manufactreing of GoodsDocument27 pagesCases On Manufactreing of GoodsSanni KumarNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Sale of Goods Act and Statute of Fraud in NigeriaDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Sale of Goods Act and Statute of Fraud in NigeriaJohn O. Ichie100% (1)

- Understanding Intention to Create Legal RelationsDocument54 pagesUnderstanding Intention to Create Legal RelationsR ZeiNo ratings yet

- Uganda Christian University Faculty of Law Contracts Law: LecturerDocument8 pagesUganda Christian University Faculty of Law Contracts Law: Lecturerkatushabe brendaNo ratings yet

- Essential elements of a contract of sale under the Sale of Goods ActDocument19 pagesEssential elements of a contract of sale under the Sale of Goods ActAlbert Venn DiceyNo ratings yet

- CapacityDocument3 pagesCapacitykeshni_sritharanNo ratings yet

- 10 Doctrine of FrustrationDocument264 pages10 Doctrine of FrustrationSri Bala Murugan David100% (2)

- Islam Ally Saleh Balhabou... Plaintiff Vs Latif Nasher Numan..... Defendant Commercial Case No.159 of 2013 Ruling Hon - Makaramba, JDocument14 pagesIslam Ally Saleh Balhabou... Plaintiff Vs Latif Nasher Numan..... Defendant Commercial Case No.159 of 2013 Ruling Hon - Makaramba, JedwardntambiNo ratings yet

- Phillips v. Brooks: Egal Spects OF UsinessDocument3 pagesPhillips v. Brooks: Egal Spects OF UsinessAbhimanyu SinghNo ratings yet

- GPR 212 Law of Torts Course Outline - Benjamin MusauDocument13 pagesGPR 212 Law of Torts Course Outline - Benjamin Musaujohn7tagoNo ratings yet

- Boulton V JonesDocument2 pagesBoulton V JonesAditya Prakash67% (3)

- R. V. Tatam (1921) 15 Cr. App. R. 132Document2 pagesR. V. Tatam (1921) 15 Cr. App. R. 132Bond_James_Bond_007No ratings yet

- Yamaha Piano Contract DisputeDocument11 pagesYamaha Piano Contract DisputeGalvin ChongNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 - FlotationDocument5 pagesTopic 6 - FlotationKeziah GakahuNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute Bhopal Report on Obligation and LiabilityDocument19 pagesNational Law Institute Bhopal Report on Obligation and LiabilityJasvinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Fisher V BellDocument2 pagesFisher V BellKim SoonNo ratings yet

- Section 73A Defence for BanksDocument7 pagesSection 73A Defence for BanksIsa MajNo ratings yet

- Law Mantra: Changing Definitions and Dimensions of Consumer': Emerging Judicial TrendsDocument13 pagesLaw Mantra: Changing Definitions and Dimensions of Consumer': Emerging Judicial TrendsLAW MANTRANo ratings yet

- Horsfall V ThomasDocument6 pagesHorsfall V ThomasANANo ratings yet

- Amity Law School: Under The Supervision ofDocument8 pagesAmity Law School: Under The Supervision ofvipin jaiswalNo ratings yet

- 058 - Durga Prasad v. Baldeo (221-228)Document8 pages058 - Durga Prasad v. Baldeo (221-228)NikhilNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court case on bank negligence and surety dischargeDocument14 pagesSupreme Court case on bank negligence and surety dischargeRam Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Child Evidence PDFDocument90 pagesChild Evidence PDFGodfrey MondlickyNo ratings yet

- Firm C6 Workshop 1 Banking Term 3Document29 pagesFirm C6 Workshop 1 Banking Term 3MUBANGIZI ABBYNo ratings yet

- Sep 15 Sale of Goods and Agency - 2105 OutlineDocument13 pagesSep 15 Sale of Goods and Agency - 2105 OutlineowinohNo ratings yet

- Kenya Presidential Election Petition No. E005 of 2022Document3 pagesKenya Presidential Election Petition No. E005 of 2022KhusokoNo ratings yet

- Law Notes Vitiating FactorsDocument28 pagesLaw Notes Vitiating FactorsadeleNo ratings yet

- Midland Bank Trust Co LTD and Another V Green (1981) AC 513Document20 pagesMidland Bank Trust Co LTD and Another V Green (1981) AC 513Saleh Al Tamami100% (1)

- Central London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House LTDDocument7 pagesCentral London Property Trust LTD V High Trees House LTDTheFeryNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Severability in Contract LawDocument9 pagesDoctrine of Severability in Contract LawParikshit ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Harvey V Pratt, Land Lord and TenantDocument6 pagesHarvey V Pratt, Land Lord and TenantRene MonteroNo ratings yet

- Abu Ramadan & Anor Vrs. The Electoral Commission & AnorDocument45 pagesAbu Ramadan & Anor Vrs. The Electoral Commission & AnorNaa Odoley OddoyeNo ratings yet

- Annie-Jen business disputeDocument8 pagesAnnie-Jen business disputejodiejawsNo ratings yet

- AgencyDocument7 pagesAgencyMuya KihumbaNo ratings yet

- Sale of Indian Goods ActDocument41 pagesSale of Indian Goods ActPisini RajaNo ratings yet

- Consideration: Chapter OutcomesDocument28 pagesConsideration: Chapter OutcomesThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- Gherulal Parakh v. Mahadeodas Maiya and Ors. 1959 AIR 781Document2 pagesGherulal Parakh v. Mahadeodas Maiya and Ors. 1959 AIR 781SHRIKANT VERMANo ratings yet

- Arcos V Ronaasen (1933) HLDocument12 pagesArcos V Ronaasen (1933) HLlostnfndNo ratings yet

- HC Order 9 Sept 2015Document30 pagesHC Order 9 Sept 2015Moneylife Foundation100% (1)

- Mistake in LawDocument27 pagesMistake in LawOwor GeorgeNo ratings yet

- MistakeDocument3 pagesMistakeshakti ranjan mohanty50% (2)

- Acceptance and Unilateral ContractsDocument12 pagesAcceptance and Unilateral ContractsGratian MaliNo ratings yet

- Case BriefsDocument22 pagesCase Briefsdarren_chan_60% (1)

- Problem Solving CompressDocument21 pagesProblem Solving CompressJaycee HowNo ratings yet

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyFrom EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Attitudes & BehaviourDocument69 pagesChapter 7 - Attitudes & BehaviourbrownshugaNo ratings yet

- Banana BreadDocument1 pageBanana BreadbrownshugaNo ratings yet

- Avon-Strategic Management CaseDocument56 pagesAvon-Strategic Management Casebrownshuga100% (2)

- Chapter 03Document68 pagesChapter 03brownshugaNo ratings yet

- Germany's Continental Shelf BoundariesDocument24 pagesGermany's Continental Shelf BoundariesAleezah Gertrude RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Election Law Compendium (2&3)Document5 pagesElection Law Compendium (2&3)Anne DerramasNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Digest Cases on JurisdictionDocument256 pagesCivil Procedure Digest Cases on JurisdictionKennethQueRaymundoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ralph J. Visconti, 261 F.2d 215, 2d Cir. (1958)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Ralph J. Visconti, 261 F.2d 215, 2d Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PRIMA FACIE AND ACTUAL DUTIES - William David Ross PDFDocument12 pagesPRIMA FACIE AND ACTUAL DUTIES - William David Ross PDFGintokiNo ratings yet

- Green Light and Red Light Controls Over Administrative and DISCRETION-3Document6 pagesGreen Light and Red Light Controls Over Administrative and DISCRETION-3Akshay SarjanNo ratings yet

- Jessica Lal Case MatterDocument18 pagesJessica Lal Case MatterLatest Laws Team100% (1)

- Complainant Vs Vs Respondent: Second DivisionDocument6 pagesComplainant Vs Vs Respondent: Second DivisionSofia DavidNo ratings yet

- Code of Criminal Procedure Project on Maintenance OrdersDocument12 pagesCode of Criminal Procedure Project on Maintenance OrdersshivamNo ratings yet

- Kreu 1 Hammurabi's Law and Mosaic LawDocument4 pagesKreu 1 Hammurabi's Law and Mosaic LawGrupi NjeNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 158911: March 4, 2008MANILA ELECTRIC COMPANYDocument1 pageG.R. No. 158911: March 4, 2008MANILA ELECTRIC COMPANYmcris101No ratings yet

- People vs. Wong Cheng 46 Phil. 729, 733Document3 pagesPeople vs. Wong Cheng 46 Phil. 729, 733Dat Doria PalerNo ratings yet

- 33 Del Rosario V LimcaocoDocument3 pages33 Del Rosario V LimcaocoAnonymous LGuYSYEdrNo ratings yet

- Cases Co OwnershipDocument141 pagesCases Co Ownershipeight_bestNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law II - Quasi OffensesDocument2 pagesCriminal Law II - Quasi OffensesJanine Prelle DacanayNo ratings yet

- Circumstances for criminal liability from failure to actDocument2 pagesCircumstances for criminal liability from failure to actTekani Trim100% (1)

- Partnership Exists Between Marketing Adviser, VP for Operations, and President in Joint Venture for Kitchen Cookware DistributionDocument2 pagesPartnership Exists Between Marketing Adviser, VP for Operations, and President in Joint Venture for Kitchen Cookware DistributionJustice PrevailsNo ratings yet

- Soriano Vs MTRCB, GR No. 164785, April 29, 2009Document33 pagesSoriano Vs MTRCB, GR No. 164785, April 29, 2009Iya LumbangNo ratings yet

- Third-Party-Notice - This-Form-Includes-The-Affidavit-Of-Service-Cts2776Document3 pagesThird-Party-Notice - This-Form-Includes-The-Affidavit-Of-Service-Cts2776api-344873207No ratings yet

- Drilon V CaDocument2 pagesDrilon V CaJane Irish GaliciaNo ratings yet

- Michele Maynard ChargesDocument1 pageMichele Maynard ChargesErin LaviolaNo ratings yet

- Ravi Gangal - RD - 130101095Document5 pagesRavi Gangal - RD - 130101095Meghna SinghNo ratings yet

- Shauf Vs Court of Appeals 191 SCRA 713.Document13 pagesShauf Vs Court of Appeals 191 SCRA 713.rj TurnoNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure - Case 19 Alcaraz V PeopleDocument1 pageSearch and Seizure - Case 19 Alcaraz V PeopleChristopher Jan DotimasNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Ethics OverviewDocument5 pagesModule 2 Ethics OverviewLeizel CervantesNo ratings yet

- Client Alert: Moore Sparks, LLCDocument1 pageClient Alert: Moore Sparks, LLCWanda HarrisNo ratings yet

- Marasigan TagaytayDocument3 pagesMarasigan TagaytaySebastian GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Advancement of Learning by Bacon, Francis, 1561-1626Document114 pagesThe Advancement of Learning by Bacon, Francis, 1561-1626Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Eric Yu v. Agnes CarpioDocument3 pagesEric Yu v. Agnes CarpioRizza TagleNo ratings yet

- Nick Gould - Ibc Paper Successful Contract Drafting and Management TechniquesDocument49 pagesNick Gould - Ibc Paper Successful Contract Drafting and Management TechniquesAlessio De MitriNo ratings yet