Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Poetry On Death of Jesus, Beautiful

Uploaded by

thepillquillOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Poetry On Death of Jesus, Beautiful

Uploaded by

thepillquillCopyright:

Available Formats

glo ry2go df o rallt hings.

co m

http://glo ry2go dfo rallthings.co m/2011/04/14/o n-pascha-melito -o f-sardis/

On Pascha Melito of Sardis | Glory to God for All Things

Among the most powerf ul meditations on Pascha is f ound in the writings of Melito of Sardis (ca. 190 AD). His writing On Pascha is both a work of genius as poetry and a powerf ul work of theology. Its subject is the Lords Pascha particularly as an interpretation of the Old Testament. His writing is a common example of early Church thought on Scripture and the Lords Pascha. I of f er a short verse, a meditation ref lecting on the f irst-born of Egypt, who die in the Old Testament Pascha. He speaks of the darkness of death, and the grasping of Hades:

If anyone grasped the darkness he was pulled away by death. And one of the first born, grasping the material darkness in his hand, as his life was stripped away, cried out in distress and terror: Whom does my hand hold? Whom does my soul dread? Who is the dark one enfolding my whole body? If it is a father, help me. If it is a mother, comfort me. If it is a brother, speak to me. If it is a friend, support me. It it is an enemy, depart from me, for I am a first-born. Before the first-born fell silent, the long silence held him and spoke to him: You are my first-born, I am your destiny, the silence of death.

T he poetry is poignant the words of death as horrif ying as any ever spoken, I am your destiny, the silence of death. When translated into existential terms, we become both the f irst-born of the Egyptians, and the f irst-born of Israel. As the f irst born of Egypt, we too of ten know our destiny, the silence of death. We know the emptiness of our lives and the hollow constructs of the ego. We know the silence of prayer not the deep mystical silence of union with God but the empty silence that hints that no one is listening. Never bef ore, it would seem to me, has the human race been more hungry f or Gods true Pascha. In an overabundance of experience, we declare ourselves to be the f irst-born of Egypt. We f ind ourselves in the grasp of a darkness we do not understand. Our lives are very of ten removed f rom the immediacy of their existence and instead live and move in the context of the digital world (whether of entertainment or other examples). We create names and roles f or ourselves in make-believe worlds. Re-enactors become some imaginary personage on the weekend, enduring reality only f or the benef its it creates within the imaginary world. Many people indeed live lives of quiet desperation simply because they have no hope and cannot imagine where hope would begin. T he siren song of modern scientists, who f ind some strange comf ort in the hope of ever-changing DNA, is just another f orm of voice, I am your destiny, the silence of death. T hose who

of ever-changing DNA, is just another f orm of voice, I am your destiny, the silence of death. T hose who stumble along with some vague hope in extra-terrestrial lif e (as though it would change the nature of our own existence) and the march of progress (the mere aggregation of technology) if they take time to notice will see again, the silence of death. In our strange, modern world, some have made peace with this silence, the last blow of the secularist hammer on the f ullness of the lif e of f aith: better the grave than the resurrection. St. Melito obviously of f ers an alternative view of the world. T he Christ who trampled down death by death, the Lord of Pascha, is f oreshadowed in the world (particularly the account of the Old Testament). T he Christ proclaimed by St. Melito is the Christ who conf ronts death itself , including the meaninglessness that we know too well in our modern world. T his Christ is God in the Flesh, who has condescended into the existence of man and grappled with the destiny of the silence of death. In the f ace of the death of His f riend, Lazarus, Christ cries out, Lazarus, come f orth! With that cry the Churchs observance of Holy Week begins. T his observance is not the mere recounting of history. T he recounting of history (the stories of the Old Testament) has been taken up by Christ into a new and f ulf illed existence. T he call to Lazarus is now a call to all of humanity. T he silence of death has been broken by the voice of the Son of God. T he day is coming and now is, when those in the grave will hear the voice [of the Son of God] and come f orth. Our angel has come to protect us f rom the devastation of the angel of death, the one who promises us only the silence of death. T he Lamb has been slain and the Cross has been signed over our doorposts. We need not go quietly into the night. On the night of Pascha, the priest stands bef ore the closed doors of a darkened Church and cries, Let God arise! Let His enemies be scattered! Let those who hate Him f lee bef ore His f ace! It is the eternal cry of God over His creation. We were not created f or death. We were not created f or meaninglessness. We were not created f or the empty imaginations of modern philosophers. We were created f or God and He has come to save us! Some years back I sat in the tomb of Lazarus. I sat and listened f or an echo of the voice which shattered death. I did not hear it with my physical ears but my heart was lif ted up in hope. All those in the graves will hear His voice. Posted on 4/14/2011 in Orthodox Christianity with 8 Comments Author comments have a tan color background for you to easily identify the posts author in the comments

You might also like

- Luminous Mysteries For KidsDocument3 pagesLuminous Mysteries For KidsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Joyful Mysteries For KidsDocument3 pagesJoyful Mysteries For KidsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Sorrowful Mysteries For KidsDocument4 pagesSorrowful Mysteries For Kidsthepillquill100% (1)

- Month of The Sacred Heart 3 Novenas andDocument243 pagesMonth of The Sacred Heart 3 Novenas andthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Luminous Mysteries For KidsDocument3 pagesLuminous Mysteries For KidsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Eucharistic Stations of The Cross, Saint EymardDocument4 pagesEucharistic Stations of The Cross, Saint EymardthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Joyful Mysteries For KidsDocument3 pagesJoyful Mysteries For KidsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Glorious Mysteries For KidsDocument4 pagesGlorious Mysteries For KidsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Sorrowful Mysteries For KidsDocument4 pagesSorrowful Mysteries For Kidsthepillquill100% (1)

- Glorious Mysteries For KidsDocument4 pagesGlorious Mysteries For KidsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Perfect Joy of ST Francis of AssisiDocument3 pagesPerfect Joy of ST Francis of AssisithepillquillNo ratings yet

- The Glorious Mysteries of JesusDocument3 pagesThe Glorious Mysteries of Jesusthepillquill0% (1)

- Catholic Apologetics PDFDocument166 pagesCatholic Apologetics PDFkavach5982No ratings yet

- Meditations On The Sacred Passion of Our Lord, WisemanDocument326 pagesMeditations On The Sacred Passion of Our Lord, Wisemanthepillquill100% (2)

- #10 The Visible Face of The Invisible God, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryDocument29 pages#10 The Visible Face of The Invisible God, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryMario VianNo ratings yet

- Cardinal Bergolio Interview by Chris MathewsDocument8 pagesCardinal Bergolio Interview by Chris MathewsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- #9 The Stations of The Cross, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryDocument9 pages#9 The Stations of The Cross, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryMario VianNo ratings yet

- Month of The Sacred Heart 3 Novenas andDocument243 pagesMonth of The Sacred Heart 3 Novenas andthepillquillNo ratings yet

- The Passion of Jesus, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryDocument30 pagesThe Passion of Jesus, Testimony of Catalina, VisionarythepillquillNo ratings yet

- #13 The Holy Mass, Testimony of CatalinaDocument15 pages#13 The Holy Mass, Testimony of CatalinaMario Vian100% (1)

- The Broken Christ, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryDocument28 pagesThe Broken Christ, Testimony of Catalina, Visionarythepillquill100% (1)

- #15 The Great Crusade of Salvation, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryDocument96 pages#15 The Great Crusade of Salvation, Testimony of Catalina, VisionaryMario VianNo ratings yet

- From Sinai To CalvaryDocument38 pagesFrom Sinai To Calvarypapillon50No ratings yet

- #14 The Great Crusade of Mercy, Testimony of Catalina, Visionary.Document130 pages#14 The Great Crusade of Mercy, Testimony of Catalina, Visionary.Mario VianNo ratings yet

- The Ark of The CovenantDocument74 pagesThe Ark of The Covenantpapillon50100% (2)

- Holy Hour, Testimony by Catalina, VisionaryDocument14 pagesHoly Hour, Testimony by Catalina, VisionarythepillquillNo ratings yet

- The Great Crusade of LoveDocument106 pagesThe Great Crusade of Lovepapillon50No ratings yet

- Springs of MercyDocument67 pagesSprings of Mercypapillon50No ratings yet

- Praying The RosaryDocument16 pagesPraying The Rosarypapillon50100% (2)

- I Have Given My Life For YouDocument26 pagesI Have Given My Life For Youpapillon50No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elevator Traction Machine CatalogDocument24 pagesElevator Traction Machine CatalogRafif100% (1)

- DR-M260 User Manual ENDocument87 pagesDR-M260 User Manual ENMasa NourNo ratings yet

- The Apu Trilogy - Robin Wood PDFDocument48 pagesThe Apu Trilogy - Robin Wood PDFSamkush100% (1)

- The Temple of ChaosDocument43 pagesThe Temple of ChaosGauthier GohorryNo ratings yet

- Innovative Food Science and Emerging TechnologiesDocument6 pagesInnovative Food Science and Emerging TechnologiesAnyelo MurilloNo ratings yet

- Nikola Tesla Was Murdered by Otto Skorzeny.Document12 pagesNikola Tesla Was Murdered by Otto Skorzeny.Jason Lamb50% (2)

- Analysis and Calculations of The Ground Plane Inductance Associated With A Printed Circuit BoardDocument46 pagesAnalysis and Calculations of The Ground Plane Inductance Associated With A Printed Circuit BoardAbdel-Rahman SaifedinNo ratings yet

- Awakening The MindDocument21 pagesAwakening The MindhhhumNo ratings yet

- Artifact and Thingamy by David MitchellDocument8 pagesArtifact and Thingamy by David MitchellPedro PriorNo ratings yet

- ADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller GuideDocument76 pagesADDRESSABLE 51.HI 60854 G Contoller Guidemohinfo88No ratings yet

- BMW Motronic CodesDocument6 pagesBMW Motronic CodesxLibelle100% (3)

- Asian Paints Tile Grout Cement BasedDocument2 pagesAsian Paints Tile Grout Cement Basedgirish sundarNo ratings yet

- Rapid Prep Easy To Read HandoutDocument473 pagesRapid Prep Easy To Read HandoutTina Moore93% (15)

- O2 Orthodontic Lab Catalog PDFDocument20 pagesO2 Orthodontic Lab Catalog PDFplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Clean Milk ProductionDocument19 pagesClean Milk ProductionMohammad Ashraf Paul100% (3)

- Life of A Landfill PumpDocument50 pagesLife of A Landfill PumpumidNo ratings yet

- Gas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosDocument319 pagesGas Natural Aplicacion Industria y OtrosLuis Eduardo LuceroNo ratings yet

- Religion in Space Science FictionDocument23 pagesReligion in Space Science FictionjasonbattNo ratings yet

- Tutorial On The ITU GDocument7 pagesTutorial On The ITU GCh RambabuNo ratings yet

- WK 43 - Half-Past-TwoDocument2 pagesWK 43 - Half-Past-TwoKulin RanaweeraNo ratings yet

- CP 343-1Document23 pagesCP 343-1Yahya AdamNo ratings yet

- HVCCI UPI Form No. 3 Summary ReportDocument2 pagesHVCCI UPI Form No. 3 Summary ReportAzumi AyuzawaNo ratings yet

- Plate-Load TestDocument20 pagesPlate-Load TestSalman LakhoNo ratings yet

- MS For Brick WorkDocument7 pagesMS For Brick WorkSumit OmarNo ratings yet

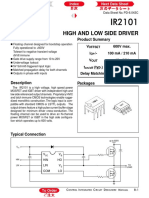

- Datasheet PDFDocument6 pagesDatasheet PDFAhmed ElShoraNo ratings yet

- Handout Tematik MukhidDocument72 pagesHandout Tematik MukhidJaya ExpressNo ratings yet

- Taking Back SundayDocument9 pagesTaking Back SundayBlack CrowNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary PsychologyDocument10 pagesEvolutionary PsychologyShreya MadheswaranNo ratings yet

- Project On Stones & TilesDocument41 pagesProject On Stones & TilesMegha GolaNo ratings yet

- An Online ECG QRS Detection TechniqueDocument6 pagesAn Online ECG QRS Detection TechniqueIDESNo ratings yet