Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bioethics. Secularism. When Bioethics Turned Secular (Interview With Fr. Joseph Tham) - Zenit

Uploaded by

jacobmohOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bioethics. Secularism. When Bioethics Turned Secular (Interview With Fr. Joseph Tham) - Zenit

Uploaded by

jacobmohCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 1 of 4

http://www.zenit.org/rssenglish-20701 ZE07100802 - 2007-10-08 Permalink: http://www.zenit.org/article-20701?l=english

WHEN BIOETHICS TURNED SECULAR

Interview With Physician Father Joseph Tham ROME, OCT. 8, 2007 (Zenit.org).- Recent news on the creation of hybrid embryos in England, and the U.S. debate on the use of embryos in research and cloning, all point to an increasingly secular agenda in life issues. Legionary of Christ Father Joseph Tham, a physician and bioethicist who recently defended his doctoral dissertation on "The Secularization of Bioethics: A Critical History," told ZENIT that this is yet another effect of the trend to push religion out of the social sphere. The author of a book on natural family planning, "The Missing Cornerstone," he teaches at the School of Bioethics of the Regina Apostolorum university. Q: Can you tell us something about the religious roots of bioethics? Father Tham: Since time immemorial, religion has been an integral part of medical ethics. Recent studies have demonstrated that even the Hippocratic oath is a product of a religious community founded by Pythagoras. In the West, Christianity has clearly influenced the founding of hospitals and the care of the sick. There is a long tradition of medical ethics based on the sacraments and the virtues since the Middle Ages. Many of the codes of ethics professed by physicians today were undoubtedly of Christian inspiration, and Catholics have produced very sophisticated manuals on medical ethics up until recently. In fact, if you look at the names of the pioneers in the early days of bioethics, which began in the late 1960s in America, a majority of them were clerics or were very committed to religion. Q: Why has bioethics turned secular? Father Tham: In part, there has been a struggle since the Enlightenment to cast religion out of all spheres of society. We can certainly see this happening in the areas of culture, science, economics, law, philosophy and education. Most people would agree that Europe and many countries in the West have become very secular today, and Benedict XVI has repeatedly spoken about this. What happened in the '60s and the '70s was that many theologians and religious ethicists turned secular. Unwittingly, they have yielded to the secular culture that was exerting a great deal of pressure for them to conform. Q: What are some of the reasons that caused them to turn away from their religious roots?

http://www.zenit.org/phprint.php

09/10/2007

Page 2 of 4

Father Tham: The causes are complex, and some of them are, as I said, the cultural ambience of the time. Remember, the '60s were kind of crazy years. Among these, I will mention two crucial events: one is the secularization of the academy and the other is the theological debates in this period. Many Ivy League universities such as Princeton, Yale and Harvard were originally founded by Protestant denominations. Religion was practiced and promoted in these schools originally, but at the turn of the last century, partly because of economic pressures and partly to become "inclusive" in the increasingly plural culture, many of these academies dropped their distinctive Christian features. Catholic colleges and universities were also affected by this desire to shed themselves of their "sectarian" image. Thus, many institutions of higher studies became severed from their religious roots. This is still hotly debated today among Catholic educators, as witnessed by the question of implementing John Paul II's apostolic constitution "Ex Corde Ecclesiae." Since most bioethicists were reared in this academic circle, many of them moved along with their institutions down the secular path. The '60s were also a period of theological experiments and controversies. At the turn of the last century, the Protestant denominations were embroiled in the questions of demythologization of the Scripture, Protestant liberalism, the Social Gospel movement, and the "death of God" theologies. Their Catholic counterparts, around the same time, were modernism and semirationalism. All these tendencies came to the fore in the '60s in leading theological currents. Vatican II sought to address many of these issues as the Church confronted the postmodern era. However, a major incident that greatly impacted the development of moral theology was the contraception controversy, especially with the issuance of the encyclical "Humanae Vitae" in 1968. Q: How did this encyclical affect the beginning of bioethics? Father Tham: As you may recall, "Humanae Vitae" was not well received by many Catholics. Some 600 theologians signed a letter of protest that originated from Father Charles Curran. This definitely undermined the Church's authority in making pronouncements in the areas of morality. As a result of this rejection of official Church teaching, many theologians began to criticize natural-law theory, especially its insistence on objective moral evil and absolute norms. What came as a result of this discontent has been termed the "new morality," or proportionalism, which has plagued many seminaries and theology departments since then. This was specifically addressed by Pope John Paul II in the 1994 encyclical "Veritatis Splendor." But the problem persists in many parts of the Church. Q: Has this affected bioethics directly? Father Tham: Certainly; proportionalism tends to emphasize the consequences and circumstances of the moral act. When carried to the extreme, it could justify abortion or euthanasia because there are more good consequences than bad ones. It is the common rationale we hear today in many of these bioethical debates where the ends justify the means. On a historical note, many of the founders of bioethics were disenchanted Catholics who

http://www.zenit.org/phprint.php

09/10/2007

Page 3 of 4

defected from the Church structures to found alternative secular bioethical institutes, and in the process marginalized the input of theology. Q: Can you give us a few examples of people who were affected by this? Father Tham: Andr Hellegers was a gynecologist who sat on the papal birth-control commission established to inform the Pope on the morality of the pill. He was quite disappointed with "Humanae Vitae" and he eventually founded the Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown. Daniel Callahan was editor of Commonweal magazine and was very upset with the encyclical. He co-founded the Hastings Center. Both the Kennedy Institute and the Hastings Center were influential in the early years of bioethics. Albert Jonsen, Warren Reich and Daniel Maguire were all former priests turned bioethicists, all of them prominent in the field for their secular orientation. Q: In your dissertation, you mentioned the secularizing effects of bioethics on theologians. Father Tham: Yes, a glaring example of this would be Joseph Fletcher. He started writing in the 1950s when the word "bioethics" did not yet exist. In those days, he was an Episcopalian priest, but by the 1980s, Fletcher had left ministry and become an atheist, humanist, and member of the Euthanasia Society. In the end, he advocated not only euthanasia but also non-voluntary sterilization, infanticide, eugenic programs, and reproductive cloning. He even went as far as proposing the creation of human-animal hybrids, and chimeras or cyborgs to produce soldiers and workers or to harvest organs. He eventually died an avowed atheist. Q: Is there a future for religion in bioethics? Father Tham: Secular bioethics has been deemed inadequate for a lot of right-thinking individuals, especially when certain academics are proposing such preposterous ideas as infanticide and eugenics. In addition, many people are dissatisfied with the inability of contemporary bioethics to address the questions of human nature, of suffering and death, and of what constitutes a good life, health and the ends of medicine. Religion has been addressing these issues for centuries. Hence, there seems to be a ray of hope for theology to play a more significant role in bioethics debates in the future. However, the challenge is great. There is a need for theologically trained bioethicists, and this would also imply the need to recuperate sound theological investigations, especially in the religiously inspired academies. I sense that the tide is changing with a new generation of laypeople and religious who are willing confront this secular and relativistic mind-set. Innovative Media, Inc. Reprinting ZENIT's articles requires written permission from the editor. PRINT THIS PAGE!

http://www.zenit.org/phprint.php

09/10/2007

Page 4 of 4

http://www.zenit.org/phprint.php

09/10/2007

You might also like

- Philosophy of The HiggsDocument3 pagesPhilosophy of The HiggsjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Kaufman M (2010) 'A Skeptics' Skeptic' Derrida Biography Review (TabletJan20)Document3 pagesKaufman M (2010) 'A Skeptics' Skeptic' Derrida Biography Review (TabletJan20)jacobmohNo ratings yet

- Abdullah's Bible (Farish A. Noor)Document2 pagesAbdullah's Bible (Farish A. Noor)jacobmohNo ratings yet

- Carl Sagan - Definitions of LifeDocument4 pagesCarl Sagan - Definitions of LifejacobmohNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of PlotinusDocument20 pagesPhilosophy of PlotinusFinkl BiklNo ratings yet

- Bonk, Jonathan, Titus Presler, Et Al (2010) Missions and The Liberation of Theology (International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 34.4, October 2010)Document56 pagesBonk, Jonathan, Titus Presler, Et Al (2010) Missions and The Liberation of Theology (International Bulletin of Missionary Research, 34.4, October 2010)jacobmoh100% (1)

- GK Chesterton's complex views shaped by 'permissive parentsDocument1 pageGK Chesterton's complex views shaped by 'permissive parentsjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- Resurrection. Michelangelo's Miracle. Chapman, Hugo. Tablet.Document2 pagesResurrection. Michelangelo's Miracle. Chapman, Hugo. Tablet.jacobmohNo ratings yet

- Philosophy. Ethics. The Virtues of Alasdair MacIntyre. Hauerwas, Stanley. First ThingsDocument6 pagesPhilosophy. Ethics. The Virtues of Alasdair MacIntyre. Hauerwas, Stanley. First Thingsjacobmoh100% (1)

- Memories of My Dad by Nick SaganDocument4 pagesMemories of My Dad by Nick Saganneuroscience2012No ratings yet

- Philosophy. Greek. Faith. Christian. The Best of Greek Thought Is An Integral Part of Christian Faith. Benedict XVI. Cheisa.Document6 pagesPhilosophy. Greek. Faith. Christian. The Best of Greek Thought Is An Integral Part of Christian Faith. Benedict XVI. Cheisa.jacobmohNo ratings yet

- Realism. Sing To The Lord A New Song. Jarman, Mark.Document1 pageRealism. Sing To The Lord A New Song. Jarman, Mark.jacobmohNo ratings yet

- The Hispanic Influence On AmericaDocument33 pagesThe Hispanic Influence On Americajacobmoh100% (1)

- St. Anselm and Romano Guardini. de Gaal, Emery. Anselm StudiesDocument12 pagesSt. Anselm and Romano Guardini. de Gaal, Emery. Anselm Studiesjacobmoh100% (1)

- Science. Religion. Science Can't Explain Creation, Says Pope. Heneghan, Tom. TabletDocument1 pageScience. Religion. Science Can't Explain Creation, Says Pope. Heneghan, Tom. TabletjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Modern. Soren Kierkegaard. Stop Kidding Yourself. Kierkegaard On Self-Deception. Marino, Gordon. Philosophy NowDocument4 pagesModern. Soren Kierkegaard. Stop Kidding Yourself. Kierkegaard On Self-Deception. Marino, Gordon. Philosophy NowjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Martin Heidegger. Luther, Martin. The Facticity of Being God-Forsaken.Document18 pagesMartin Heidegger. Luther, Martin. The Facticity of Being God-Forsaken.jacobmoh100% (1)

- Science. Cosmology. Our Special Universe. Townes, Charles H. Wall Street JournalDocument2 pagesScience. Cosmology. Our Special Universe. Townes, Charles H. Wall Street JournaljacobmohNo ratings yet

- Culture. Technology. A Writing RevolutionDocument2 pagesCulture. Technology. A Writing RevolutionjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Philosophy in SeminariesDocument5 pagesPhilosophy in SeminariesjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Darwin. Religion. Voyage From Faith. Spencer, Nick. TabletDocument2 pagesDarwin. Religion. Voyage From Faith. Spencer, Nick. TabletjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics. Good. Medicine's Intrinsic Good. Iglesias, Teresa. CBHD.Document4 pagesMedical Ethics. Good. Medicine's Intrinsic Good. Iglesias, Teresa. CBHD.jacobmohNo ratings yet

- Assaf, Andrea (With Brian Scarnecchia) - The Absurd Fate of Frozen Embryos. Bioethics, Reproduction, Surrogacy. ZenitDocument4 pagesAssaf, Andrea (With Brian Scarnecchia) - The Absurd Fate of Frozen Embryos. Bioethics, Reproduction, Surrogacy. ZenitjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Goldman, David P. God of The Mathematicians. Kurt Godel. Ontological Argument. Philosophy of God. ScienceDocument6 pagesGoldman, David P. God of The Mathematicians. Kurt Godel. Ontological Argument. Philosophy of God. SciencejacobmohNo ratings yet

- Kavanaugh, John F. Uninformed Conscience. Morality, Ethics, Aquinas. AmericaDocument2 pagesKavanaugh, John F. Uninformed Conscience. Morality, Ethics, Aquinas. Americajacobmoh100% (1)

- Notes To Modern PhilosophyDocument95 pagesNotes To Modern PhilosophyjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Medieval Arabic/Jewish PhilosophyDocument5 pagesMedieval Arabic/Jewish PhilosophyjacobmohNo ratings yet

- Catholic Philosophy. Ecclesiae Ex Corde. Fides Et Ratio. Faith and Reason in Theory and Practice. Prusak, Bernard G.Document10 pagesCatholic Philosophy. Ecclesiae Ex Corde. Fides Et Ratio. Faith and Reason in Theory and Practice. Prusak, Bernard G.jacobmohNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Preparing The Dining RoomRestaurant Area For ServiceDocument121 pagesPreparing The Dining RoomRestaurant Area For ServiceAel Baguisi60% (5)

- Report On Education DeskDocument5 pagesReport On Education DeskBupe MusekwaNo ratings yet

- K To 12 Nail Care Learning ModuleDocument124 pagesK To 12 Nail Care Learning ModuleHari Ng Sablay92% (97)

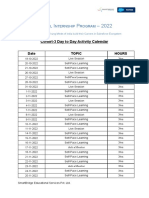

- Virtual Internship Program Activity CalendarDocument2 pagesVirtual Internship Program Activity Calendaranagha joshiNo ratings yet

- ECO 3411 SyllabusDocument5 pagesECO 3411 SyllabusnoeryatiNo ratings yet

- Jpia Day 2019 Narrative/Accomplishment ReportDocument2 pagesJpia Day 2019 Narrative/Accomplishment ReportFrances Marella CristobalNo ratings yet

- My Educational PhilosophyDocument6 pagesMy Educational PhilosophyRiza Grace Bedoy100% (1)

- DLL - Mapeh 1 - q4 - w5 - For MergeDocument8 pagesDLL - Mapeh 1 - q4 - w5 - For MergeTser LodyNo ratings yet

- Research Evidence On The Miles-Snow Typology: Shaker A. Zahra A. Pearce IIDocument18 pagesResearch Evidence On The Miles-Snow Typology: Shaker A. Zahra A. Pearce IIAnonymous 2L6HqwhKeNo ratings yet

- Vocal Anatomy Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesVocal Anatomy Lesson Planapi-215912697No ratings yet

- DEPED Mission and Vision: Educating Filipino StudentsDocument85 pagesDEPED Mission and Vision: Educating Filipino StudentsJohn Oliver LicuananNo ratings yet

- Kunal MajumderDocument4 pagesKunal MajumderMohit MarwahNo ratings yet

- Strategic PlanDocument9 pagesStrategic PlanStephanie BaileyNo ratings yet

- PICPA Negros Occidental Chapter Board Meeting Minutes Highlights Tax Updates and January SeminarDocument2 pagesPICPA Negros Occidental Chapter Board Meeting Minutes Highlights Tax Updates and January SeminarYanyan RivalNo ratings yet

- School Tablon National High School Daily Lesson LogDocument3 pagesSchool Tablon National High School Daily Lesson LogMary Cris Akut MafNo ratings yet

- ARB 101 SyllabusDocument6 pagesARB 101 SyllabusnaeemupmNo ratings yet

- College Code College Name BranchDocument32 pagesCollege Code College Name BranchRaju DBANo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 2Document5 pagesLesson Plan 2Oana MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Values 2 PrelimDocument12 pagesLesson 2 Values 2 Prelimbenny de castroNo ratings yet

- Jesse Robredo Memorial BookDocument141 pagesJesse Robredo Memorial Bookannoying_scribd100% (1)

- Photo Story RubricDocument2 pagesPhoto Story RubricAnnette Puglia HerskowitzNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal SampleDocument6 pagesResearch Proposal SampledjebareNo ratings yet

- OJT Weekly Log - April10-18Document4 pagesOJT Weekly Log - April10-18efhjhaye_01No ratings yet

- Google Scholar AssignmentDocument2 pagesGoogle Scholar Assignmentapi-355175511No ratings yet

- LEARNING MODULE I Sessional Diary Structure & Design - Paper Code BL 805Document6 pagesLEARNING MODULE I Sessional Diary Structure & Design - Paper Code BL 805Bwinde KangNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Novice Teachers PDFDocument6 pagesChallenges of Novice Teachers PDFLennon sorianoNo ratings yet

- 2022-2023 SHS Action PlanDocument6 pages2022-2023 SHS Action PlanHarmony LianadaNo ratings yet

- STC Final SSRDocument100 pagesSTC Final SSREdurite CollegeNo ratings yet

- BUS 102 Exam OneDocument1 pageBUS 102 Exam OneSavana LamNo ratings yet

- Long Test: Botong Cabanbanan National High School Senior High School DepartmentDocument3 pagesLong Test: Botong Cabanbanan National High School Senior High School DepartmentEF CñzoNo ratings yet