Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter3 Pricing The Contract

Uploaded by

Mdms PayoeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter3 Pricing The Contract

Uploaded by

Mdms PayoeCopyright:

Available Formats

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON FINANCIAL ASPECTS OF PROJECT ENGINEERING AND CONTRACTING CIV ENG E237 CHAPTER 3 PRICING THE

CONTRACT George Solt 1 PRICE In any competitive business it is crucially important to know how to price the product: a high price means no one will buy it, and the company will fall short of its turnover target and so fail for lack of contribution. A low price means that the company will fail for lack of contribution anyway. This problem is particularly difficult in contracting, for the following reasons: 1.1 Competition Contracting is highly competitive. A contractor needs relatively little capital to start trading - he has no need of land, fixed premises, machinery, or stock. He needs working capital to carry out the work, but only after he has actually obtained contracts. (Remember the cowboy roofing mender who demands money before he can start, so that he can buy materials.) It is relatively easy to start up a contracting company. I know that because Ive done it. Four partners and I started a company in 1971. It not only survived, but even ended up with people thinking of it as a bit old-fashioned and stuffy. It is still going quite well. In my specialised field the UK used to be an isolated market with four or five well-established contractors. With the advent of the EU, the market has now spread to the entire EU and three of these companies (including my old company) were unified under French ownership to be competitive in this wider area. But theyve all been closed down - the fact that the huge conglomerate which owned them are in serious trouble wont have helped.. Before that happened, however, new competitors started up at about 2-year intervals. Most of them disappeared again after a few years in business, but in effect there was always at least one cowboy contractor offering contracts at cut-throat prices1. That' s why it has been said that contracting is the last business area in which there is real competition. With such fierce competition, profitability (i.e. profit as a percentage of turnover) will always stay low, but this is no deterrent when you consider the high potential return on capital (see Table 2.2). On the other hand, low profitability means that the margin for error is small, and contracts can easily swing into loss. In many real-life cases it only takes one or two bad contracts to break a company - even a big one. 1.2 The Unknown No two contracts are the same. Even if the technical content of a contract is the same as that of a previous one, there will be different site conditions, labour conditions, costs may have shifted in the interval, the time of year and the weather play a part, and so on. Compare this to manufacturing, which takes place in a more controlled environment. That makes it easier to give an accurate estimate of the cost of producing the product.

In hard times, even the reputable ones have to quote cut-throat prices just to survive.

C510103

Page 2 of 10 October 2003

1.3 Sub Contractors Contracting involves chains of sub-contractors. A Contractor prepares cost estimates by breaking down the proposed job into known components. Materials and labour are the most obvious, but in addition almost all engineering contracts involve sub-contracting, the sub-contractor may sub-contract out in turn, and so on. I have done several stints as Expert Witness in legal cases, and from time to time I will refer to the two biggest of these, because they provide a lot of useful examples. Both of them dealt with the 2 construction of new power stations by big contractors with a turnkey contract. My concern is always limited to the plant which produces highly purified water for the stations boiler feed, and this plant is normally designed and purchased by the following route: the main contractor issue enquiries for a price to the boilermakers the boilermakers issue enquiries to the water treatment plant manufacturers the water treatment plant manufacturers issue enquiries to the pressure vessel fabricators, etc.

Each of these enquiries yields an offer which is incorporated in the price for the next offer back up this chain. In a project as complex as a power station there are of course dozens such chains - the building, the turbine, the generating set, the switchgear etc. etc. The main contractors who are bidding for the station put it all together to make their turnkey offers. When the turnkey contract for the power station is signed with the successful contractor, all these enquiries go out again. This time everyone in the chain knows that the project is really going ahead and tries much harder, so it happens quite often that the contractor whose offer was used in building up the total contract price fails to get the job in this second round. A lot can go wrong in a system where everyone is trying to undercut everyone else. Each contract is generally placed with whoever offers the lowest price - and that could be the result of a mistake. Errors in estimating almost always go one way: something gets forgotten, and so the price tends to be too low. When the order is executed, there isnt enough money to do it properly, so there is bound to be trouble of some kind. 1.4 Purchasers buy the Cheapest In Britain public bodies were until recently required by law to select the lowest tender which appears technically satisfactory. It is very hard for them not to go blindly for the cheapest. That may be an offer from an incompetent cowboy who isn' t quite up to the task, or from the one with a big mistake in the estimate, or both. Companies are not required to go for the cheapest offer, but they tend to do it just the same. In the Netherlands, by contrast, they may go for a middle price, in the hope of avoiding the disasters which would follow. 1.5 The competition is unknown. In standard commodities like cars or tins of baked beans, you look at the competitors' price and work to that. In the motoring magazines you can read that such and such a car is aimed at the Escort market - that is the lower-priced middling sized family five-door car. Other manufacturers know the cost of an Escort and design and price their cars to compete with that. In competitive tendering this is (theoretically) not the case, though there are devious means of finding out what the competitors prices are.

In theory Turnkey means that the contractor does everything up to the point when the client turns the key in the front gate and takes over the finished contract in full running order. The practice is much more complicated.

C510103

Page 3 of 10 October 2003

2 THE COMPETITIVE TENDER SYSTEM This is the traditional method of placing contracts, and is legally required for a lot of public work, so you should have an idea how the system works. I will talk about alternative systems later. A client who wants to commission a large project issues a specification to define what it is that he wants, and invites contractors to tender. He may write the spec himself, or employ consultants to do so. There is usually a date by which the tenders have to be in, the tenders have to be sealed and the enquiry may actually say that the tenders will only be opened on that date. The specification may set out in detail exactly what the client wants, or it may set out only the function which is to be met, leaving the contractor to select what he thinks would be the best solution to the problem. The latter option "Design and Build" is gaining ground, because the contractor is usually more expert in some specialised field than his client, and may well be more expert than the consultant (if there is one). An interesting sideline illustrates what has happened in my own specialised field of industrial water purification, in which the biggest single application is for power stations. In Europe the specification is generally functional: the client specifies the source of raw water, and the flow and quality of purified water needed. The contractor is invited to offer a plant on the basis of whatever process he thinks is the best. In the USA, on the other hand, it has been common practice to specify the process and the plant in very great detail. In Europe, therefore, the contract is likely to go to the offer with the best process, whereas US contractors have no choice in the content of their tender, and rely on pricing to get the contract. As a result European technology in my field is literally decades ahead of the US.. The reason is clear: the consultants or whoever writes a detailed specification will always play safe with known technology, which leaves no incentive for technical innovation, whereas in Europe the contractors has to offer plant which out-performs the competitors' . Needless to say this technological inequality is already correcting itself. In theory no one sees the competitors tenders. In practice there are some ethical and many not-soethical devices by which tenderers can ferret out details of competitors'offers, and the clients can play some nasty tricks as well. For example, I was consulting to my old company who were bidding for a plant to meet a new application. I had been doing research in this specific application, and I knew I had a more economical process than the opposition. We thought we had the contract in the bag, but the client for some reason wanted to place the contract with a competitor, so he simply passed them the details of my (unpatentable) process and told them to re-tender. He might even have revealed what price he would like to see. It was unethical, but not actually illegal. We used to expect to win one tender in four, which I think is fairly typical, and we got no reward for the work which we put into the other three unsuccessful tenders3. And tendering is an expensive business - the standard enquiry specification issued by big petrochemical companies, for example, may be a three-volume document full of detail, most of which is usually irrelevant to the particular case. It can take weeks to study this to make sure you' ve found and understood all the relevant bits, before you can put together an offer which conforms to the spec. We used to distinguish between those offers when we knew the client was going to place an order, and those where the client was just getting a price (see Chains of sub-contractors, above). Much less work went into the latter, or we should never have been able to cope. The tender system can be very harsh. In the 60ies and 70ies the CEGB (the nationalised electricity generating undertaking, now broken up into several companies) built so many power stations that for a time they were the biggest single purchaser of industrial water treatment plant in the world. This

3 In Holland its not uncommon for contractors to club together and agree on a sum which covers the cost of all of them tendering. Each offer includes this sum, which is then shared out between them out of the winner' s contract price. If this is done openly, it is quite legal, but I have never heard of it being done in Britain. The Dutch are a very sensible nation.

C510103

Page 4 of 10 October 2003

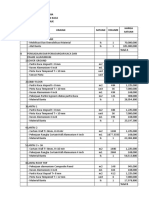

made the CEGB very powerful, and they became quite ruthless. They insisted on very harsh contract conditions, bought the cheapest and then nailed the contractor to the contract. Four major UK contractors dealt with the CEGB over this period, and the CEGB broke them all. We all realised that their contract conditions were unreasonable, but as a virtual monopoly client they could insist on the full terms being met. When the had ruined a couple of the UK companies, a big French contracting company saw an opportunity to get a foothold in Britain. They thought he had the skill or the clout to deal with the CEGB. They won several contracts from the CEGB, got into dispute with them, and lost out. The French company closed down their branch here and the UK industrial water treatment plant industry never recovered properly from the disaster of serving the CEGB. This is old history, but Im sorry to say that our present experience with the big public water companies ( who are also extremely big and powerful) is not uniformly good either. The moral is that very powerful clients can do a lot of damage to their contractors. Tendering can be a lottery, and is open to abuse. So much for the background to pricing. 3 MAKING UP A PRICE Table 1 is a copy of the price make-up sheet which we used in my old company when it only had a turnover of about m 5. Its fairly basic, but shows the main factors which have to be considered - the bigger the company, and the bigger the individual contracts, the more sophisticated all this gets. Remember that this sheet deals with contracts for the design and manufacture of chemical process equipment, so most of the contract consists of equipment like steel tanks, pumps, valves, pipes and instrumentation and control equipment - all bought as sub-contracts from their fabricators. Almost all our contracts included at least some design effort. Most commonly we worked to a functional specification, so our offer was based on our own process design. The instrumentation and control gear usually involves expensive detailed design, which can cost more than the design of the hardware. TABLE 1 SIMPLIFIED PRICE MAKE-UP SHEET ITEM 1. 2. 3. 4a. 4b. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. Bought-out Costs (BOC) Deliveries Buying costs @ ...... % of 1 Plant Design Automation and Control Design SUB-TOTAL 1. - 4. .................. +Contribution@...... % of 5. + Contingency @ ..... % of 5. ................. Price Fixing @ ....... % of 7. Sundry Extras Royalty Insurance Capital Charges Penalties Contribution Adjustment Agents commissions Negotiation TENDER PRICE

I have not copied certain key percentages which used to feature on this sheet because even after all these years they are still confidential. I will now run down the detail, following the numbers on the sheet. Remember that this is one companys sheet The important thing is to recognise the items for which any price make-up has to cater, even if other companies might call them by different names and set them out in different groups.

C510103

Page 5 of 10 October 2003

1.

"BOC" stands for "Bought-Out Costs" - that is, the cost of items to be purchased or subcontracted out. It was generally the biggest single cost item. This is the major difference between contractors and consultants - in consulting it will be the smallest or non-existent. We occasionally, got "Design-only" contracts, when in effect we became consultants. is the cost of getting the stuff to the place where we might be assembling equipment, and/or to the site. is the cost of the "Purchasing" cost centre, whose task is to procure the items costed in 1. and 2. (A cost centre is a way of estimating the cost of work done within the company, which I will explain shortly).

2. 3.

4a & b are the estimated costs of plant and electrical design cost centres respectively. Originally it was a single cost centre, but we split it into two because control engineering costs a lot more than standard engineering and therefore demands a higher rate per man-day. 5. 6. is the sub-total so far, and totals the costs which can be directly attributed to actually doing the work. is of course the key number: When we planned the year' s trading we set the average percentage contribution on planned turnover which would give us the necessary total contribution over the year - it used to be around 25%. That may be high compared with straightforward civil engineering contractors, because of the specialised nature of our trade, and the technical effort involved. Profit isn't mentioned anywhere. A single contract makes no profit, so it's senseless to speak of profit at this stage. 7. The contract contingency was calculated using another standard percentage, but often increased or decreased because of the nature of the job. The standard number would be a guide to the Auditor, who might query why the proposed Provision on some specific contract was significantly higher or lower. Be careful with this phrase, which has two meanings! What we meant on this in-house form was an additional sum in the tender price if we were to hold the cost fixed rather than tying it to a price escalation formula (which I will describe later). Inflation was high at the time when we used this sheet, whereas at present these formulae aren' t thought necessary by anyone, so we can ignore it. I hope we wont get back to high inflation again, but you never know. What people generally understand by "Price Fixing" is an illegal practice, when contractors get together secretly and rig their prices high: the one who gets the contract then pays off the others. That is legal only if it' s done openly and with the client' s consent, which is rare in the UK. In Holland, the contractors sometimes agree to add a sum to all their offers, out of which the successful bidder can pay all the unsuccessful ones something to cover their cost in producing the offer. The sensible Dutch do this openly, when it is completely legal. 9. Is a list of other costs - packaging, shipping, providing operating and maintenance instructions ("O & M"), etc. I don' t know why they weren' t included in 1. and 2. O & M can be quite expensive. When buying a car or a telly you get the instruction book free. With specialised plant the O & M manual can cost thousands. Specialised sub-contractors such as the makers of metering and monitoring instruments charge for their O & M manuals. We often engage the services of a specialist writer of O & M manuals to collate the separate bits and write the complete set. came into force if we were using a licensed design. The company had a general insurance policy, but sometimes we had to take out additional insurance because of special risk, or because the client required it.

8.

10. 11.

C510103

Page 6 of 10 October 2003

12.

This is an extremely important subject about which we are going to talk quite a lot more. Any project takes up capital which has to be raised by the client or the contractor, or both. The conditions of payment spell out how this burden is shared and therefore who pays the interest for it. The contractor usually has to have to bear some of that burden and this item served for us to estimate how much it was going to cost. That' s self-explanatory: if there are penalties on performance or on completion date you need extra contingency to cover the risk of going down on them. required us to use our judgment in lowering or raising the contribution. If, for example, the contract contained a very high element of sub-contract, we couldn' t afford to slap our standard contribution on top of the sub-contractor' s - after all, he was going to do most of the work and take most of the risks. The same applied if there was a large element of standard, 4 risk-free material cost together with a minimum of engineering effort . Or we might particularly want the contract and were prepared to cut our contribution to get it. Conversely, if we knew we were going to get the order anyway, we might as well put the price up and make a few more bob on it. Or it might be a job we really didn' t want: then we' d put the price up so if we did accidentally get the contract, we would at least be well rewarded.

13. 14.

15. 16.

is self-explanatory: we often used local agents - when exporting to foreign countries like Scotland.. is the leeway available for the salesman to negotiate away if necessary. If we got into serious negotiations he would usually come under pressure to cut the price, so we added this into our tender price, knowing it might have to come out again. is the bottom line: the offer price. Sometimes we had additional site work to do, which for some reason or other figured as an extra, in 14.

17.

The bought-out cost is of course usually the most important one, but I myself am not going to say anything about that - its the province of the Estimators - a skilled and specialised trade. Most of these other items are obvious and/or not particularly important. The ones which I will discuss in a more detail, are: the cost centres (3.) and (4.) The standard contribution (6.) Finance costs (12.)

4 ALLOCATING OVERHEADS I must remind you that I define overheads as: all the companys costs which you can't allocate to any particular job. But do remember that this is not the generally accepted definition. Overheads are normally taken to be the costs incurred in operating a company which are not affected by the amount of business it does. In ideal circumstances that comes to the same thing as my definition.

Many of our plant used of ion exchange resins, which have a limited working life, so we were often asked to tender for the supply of replacement charges to our old contracts. All the work that this entailed was to place an order on the resin manufacturer to deliver direct to site. The job therefore involved minimal work or risk. On the other hand, we were in fierce competition with other suppliers, and that brought the contribution down, from our standard 20-odd% - sometimes to as little as 3%.

C510103

Page 7 of 10 October 2003

4.1 Costs Of Running A Car An easy way of showing the problems of allocating overheads is to calculate the cost of running a car. In 1996 the mileage rates which various organisations pay for using a privately-owned car on the companys business varied between about 24 p and 42 p per mile . Why? Table 2 shows some arbitrary assumptions which I make for the major costs of running a small car, with simple numbers to avoid lots of arithmetic. Real costs might be quite different - an old banger costs more to service but less in depreciation, and so on. TABLE 2 CAR RUNNING COSTS DIRECT COSTS OVERHEADS fuel, 10 miles/litre @ 70p/l service, oil, and tyres Insurance and road fund licence Depreciation p/mile p/mile pa pa 7 2 500 2000

The "direct" costs are only incurred when you actually drive the car. The other two must be paid whether you use it or not. They cant be allocated to a particular trip, so theyre "overheads". Table 3 shows how this works out. TABLE 3 COSTS PER MILE Annual mileage Fuel, pa Service etc, pa Insurance etc, pa Depreciation, pa TOTAL, pa Cost p/mile 5,000 350 100 500 2000 2950 59 10,000 700 200 500 2000 3400 34 20,000 400 400 500 2000 4300 21.5

So, depending on your assumptions, the cost of mileage can be made to be pretty well whatever you want. In fact there is no "true" mileage cost: it depends on your overheads and how you allocate them. Some companies say: you' ve got a car and probably do the national average mileage for your private use (a bit over 10,000 miles per year). We' re only going to pay you the "marginal" cost of running your car for a few miles over and above that. To this, you could reasonably reply that if the company didn' t oblige you to use your car, you' d take it off the road for the winter, thus saving on insurance and licence. Also, the additional mileage will put up the depreciation per year. If you use it for work you may need a more expensive insurance. In fact the "fixed" costs aren' t really fixed at all, and you should get a higher mileage allowance. 4.2 Overheads and Pricing - a Simple (and bad) System In a small company in which I worked in my early days we estimated the BOC (1.) and added 50% to get the selling price. Very simple, but its results were wildly inaccurate. One of our bigger and costlier departments was the engineering office, and pricing "Bought-out-cost plus 50%" doesnt allow for the difference in engineering effort needed by different contracts. Because the cost of other activitites as well as engineering were treated as overheads, we needed to add 50% to the basic cost estimate to get in the necessary contribution - which is a much higher figure than any I have quoted to you so far. The system overpriced contracts involving little design work, and underpriced the ones with a lot. We werent so stupid as to allow that to happen, so in practice we compensated for that by adjusting the BOC + 50" price by sheer guesswork - not a very good way of working out vitally important sums.

C510103

Page 8 of 10 October 2003

Similar arguments apply when allocating any other overhead costs to contracts. Some contracts make more demand on the overhead structure than others, and overheads aren' t really fixed anyway. 4.3 What Cost Centres do. The uncertainty which results from allocating overheads can never be eliminated, but if the percentage of overhead in a price calculation is small, the error becomes relatively smaller. Management Accounts systems therefore try to allocate as many of the costs as they can. to some job or other. Replacing some overheads by Cost Centres gives a partial solution. The official definition of overheads leaves some grey area. For example, in my old company I carried out research and development, and that is a true overhead - by both definitions. In the early days our engineering office worked on designs for bids which we were going to make, and also the design for actual contracts. The former activity couldnt be allocated to any job, because a majority of bids never produce a contract, but the latter of course could - if we could separate the two from one another. What is more, specialised designers are skilled professionals. You don' t hire and fire them, but train them and keep them as permanent staff. That makes them seem at first sight to be "overhead costs" in the sense that they are costs which my company had to meet regardless of whether it gets a particular contract or not. Until we had a more sophisticated accountancy system, the engineering office had to be counted as an overhead. That in turn would mean that we had to add a larger contribution to a smaller cost base when pricing up our contracts, and introduce a measure of inaccuracy, because it did not distinguish between those contracts which used a lot of time in the engineering office, and those which didnt. As an extreme example, I just described the pricing of ion exchange resin for re-charging existing plant, but every real contract would take up a different amount of effort which we had no means of costing. Similar arguments apply to other activities in a company. Cost Centres reduce the sum of overheads as I define them, without in any way changing the way the company actually operates: they are only a paper exercise. "Reducing" the overheads in this context means shifting their cost to another category in the management accounts- it doesnt reduce the total costs in any way, but does give the companys management a clearer understanding of where their money is going. 4.4 How Cost Centres Work The system of Cost Centres used on the price make-up sheet overcomes this difficulty. It brings the necessary contribution down from the 50% which we used in my previous company with its simple system, to below 25%, and a more sophisticated system might bring it down even more. I will take the engineering office as an example, and this is how it works. To estimate the engineering cost to be allocated to a contract, we have to be able to measure the work involved, and need to know three things: how do we measure the work done by the engineering office? how much work will the contract need, and what does the unit of work cost?

So the first thing we must settle on is a yardstick for measuring design work. We used the engineering man-hours needed to do the job. Next, to calculate the cost of each man-hour, we tot up the total annual costs of the engineering office - the staff (including those not directly productive - chief engineer, trainees, secretary etc), printing and other material costs, and so on. Salaries have to include all associated costs like National Insurance, pensions, etc.

C510103

Page 9 of 10 October 2003

Then we tot up how many allocatable man-hours the office actually turns out per year. We can' t just take the man-hours in a nominal man-year and multiply by the number of design engineers. The theoretical working year at 37 hrs/week is about 1,800 hours per man per year. but the time you can actually allocate to jobs is a less because of "slippage" - time spent sick, or training or in meetings, or working on old jobs which can' t now be allocated, etc. In 1998 the cost of allocatable man-hour in the engineering office worked out at over 25 per hour, which was more than double the engineers nominal salary cost. As you will see, this internal cost per engineering man-hour is continuously checked by the system. I told you before, that when we found that the engineers who were designing instrumentation and control gears were much more expensive than the ones doing layout and piping diagrams, we split design function into two separate cost centres. Once the system is operating, records from previous contracts allow us to estimate the engineering man-hours expected to be used for a particular contract. We multiply them by the internal cost per man-hour and can now enter a figure for design cost into the price make-up sheet. Other cost centres use other units to measure their output. The Purchasing department' s annual output is measured as the value of the goods and services it purchases in the year, to give us a "purchasing" cost in terms of a percentage of the value of goods purchased - it might be around 0.1 to 0.2%. That, too goes into the price make-up sheet. The essential elements of creating a cost centre are: to take a part of the company which has an identifiable and measureable output, and decide what units you use to measure the output to treat it as a non-profit-making unit which just recovers its costs Add up all its annual costs and divide them by the attainable output to calculate the cost per unit of output

I have quoted some actual numbers to give you an idea of the orders of magnitude involved, but in any particular case the actual numbers depend on how the system is set up. For example, a more sophisticated system might also take into account the cost of the area of office floor space occupied by the engineering cost centre. That would increase the costs per engineering man-hour while reducing the general overheads. That in turn would increase the direct cost in the price make-up, but reduce the percentage contribution required. You could go further and allocate the cost of heating and lighting in proportion to the area of office space, and so on, depending how sophisticated you think it is worth making the accounting system. I have worked with a company which made every member of staff, from the chief executive down, book all working hours to some allocation or other, which I thought was rather silly. The more sophisticated the system, the more it will cost to operate, so you have to match the complexity of the system to the company' s needs. 5 MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTS Cost centres are an important part of management accounts. My company' s monthly management accounts included a statement for each cost centre which compared the output actually booked in the month with the estimated output, and the actual cost with the estimated cost. This would show whether each centre was under- or over-recovering its costs, and allowed us to update the costs accordingly if we thought it necessary. Our management accounts also compared the (man-hours worked so far) with the (man-hours planned) on individual contracts. Any serious difference would raise an alarm. Suppose for example a contract is estimated to need 800 engineering man-hours, and half-way during the contract period it is expected to have used 600. If we have only spent 200, we must be getting behind schedule. Or, if we have already spent 800, we will probably over-run on man-hours and ought to find out why. Management accounts are therefore essential aids to management, and the cost centres are a useful tool.

C510103

Page 10 of 10 October 2003

I have attached some of our old Management Accounts sheets to these notes. (High inflation since then makes the figures seem amazingly low). Our financial year started in October, so on Schedule 6. we were nine months into the year. You will see that on paper the cost centres have under-recovered their costs (though only by a small margin). This is important in that it might mislead us into underestimating their costs for future work. The remedy would be to raise the rates, and we might have decided to do that - I can' t actually remember. But the error in the rates is small, and I expect we kept them the same for the last three months of the year and waited until next year before adjusting them. It' s only a paper exercise, after all. We shall be looking at Management Accounts in more detail in a later lecture.

You might also like

- HVAC ManualDocument107 pagesHVAC ManualWissam JarmakNo ratings yet

- BSR IctadDocument136 pagesBSR IctadMdms Payoe100% (5)

- What is an IP PBXDocument3 pagesWhat is an IP PBXdugoprstiNo ratings yet

- HVAC - Duct ConstructionDocument75 pagesHVAC - Duct ConstructionGaapchu100% (1)

- Check Your English Vocabulary For LawDocument81 pagesCheck Your English Vocabulary For LawMaria Cecilia Arsky Mathias Baptista95% (42)

- Management Theory and Practice PDFDocument533 pagesManagement Theory and Practice PDFMdms Payoe88% (50)

- Project Procurement Management - Contracting, Subcontracting, Teaming - CDocument285 pagesProject Procurement Management - Contracting, Subcontracting, Teaming - CFox Alpha Delta90% (31)

- Fundamentals of Building Contract Management PDFDocument454 pagesFundamentals of Building Contract Management PDFMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- DW144 Smacna 2005Document32 pagesDW144 Smacna 2005Angel Daniel GarciajoyaNo ratings yet

- Hudson's Building and Engineering Contracts PDFDocument961 pagesHudson's Building and Engineering Contracts PDFMdms Payoe96% (27)

- How To Use A Partnering Approach For Construction ProjectDocument34 pagesHow To Use A Partnering Approach For Construction ProjectMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Building Contract Management PDFDocument454 pagesFundamentals of Building Contract Management PDFMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Major Steps TimelineDocument9 pagesFIDIC Major Steps TimelineMdms Payoe50% (2)

- Collin Cobuild English Grammar PDFDocument255 pagesCollin Cobuild English Grammar PDFMdms Payoe100% (1)

- Techniques of Value Analysis and Engineering by Lawrence D MilesDocument383 pagesTechniques of Value Analysis and Engineering by Lawrence D MilesGeorge Mathew86% (37)

- Procurement Methods PDFDocument4 pagesProcurement Methods PDFMdms Payoe0% (1)

- Construction Law - Macmillan Series PDFDocument260 pagesConstruction Law - Macmillan Series PDFMdms Payoe100% (1)

- Techniques of Value Analysis and Engineering by Lawrence D MilesDocument383 pagesTechniques of Value Analysis and Engineering by Lawrence D MilesGeorge Mathew86% (37)

- Hudson's Building and Engineering Contracts PDFDocument961 pagesHudson's Building and Engineering Contracts PDFMdms Payoe96% (27)

- Drafting Engineering Contracts PDFDocument253 pagesDrafting Engineering Contracts PDFMiraj100% (1)

- Key Dates and Periods of Time at Commencement PDFDocument3 pagesKey Dates and Periods of Time at Commencement PDFMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Power PointDocument40 pagesFIDIC Power PointButch D. de la Cruz100% (4)

- Who Bears The Cost of Investigating For DefectsDocument2 pagesWho Bears The Cost of Investigating For DefectsMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- The Final ChapterDocument3 pagesThe Final ChapterMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- Claims in PerspectiveDocument244 pagesClaims in PerspectiveMdms Payoe92% (12)

- The Dangers of Withdrawing A TenderDocument2 pagesThe Dangers of Withdrawing A TenderMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- Defective Work - Minimising The ProblemsDocument5 pagesDefective Work - Minimising The ProblemsMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- Implication in Fact As An Instance of Contractual InterpretationDocument28 pagesImplication in Fact As An Instance of Contractual InterpretationMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- Quantity Surveyors Project Manager DutiesDocument3 pagesQuantity Surveyors Project Manager DutiesMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- BondsDocument5 pagesBondsMdms PayoeNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Cables Qutation-NationalDocument2 pagesCables Qutation-NationalMuhammad Abubakar QureshiNo ratings yet

- Session No. 4 / Week No. 4: 1. World Economies 2. Classification of World EconomiesDocument10 pagesSession No. 4 / Week No. 4: 1. World Economies 2. Classification of World EconomiesMerge MergeNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 2Document6 pagesChapter1 2Young Joo MoonNo ratings yet

- CH 6 Reverse Logistics PresentationDocument27 pagesCH 6 Reverse Logistics PresentationSiddhesh KolgaonkarNo ratings yet

- Research On AgingDocument5 pagesResearch On AgingAslam RehmanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Economics: Course OutlineDocument2 pagesIntroduction To Economics: Course OutlineLoey ParkNo ratings yet

- Guide On Philippine TaxationDocument15 pagesGuide On Philippine TaxationmyfrankpovNo ratings yet

- Brokerage Fees 49 Samiver Invoice CMA CGM InvoiceDocument1 pageBrokerage Fees 49 Samiver Invoice CMA CGM InvoicerifablackNo ratings yet

- LLB 12+5 - 2 - PDFDocument137 pagesLLB 12+5 - 2 - PDFNitesh JaisinghaniNo ratings yet

- Understanding Valuation Implications of M&A Payment Methods and Cross-Border Acquisition IssuesDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Valuation Implications of M&A Payment Methods and Cross-Border Acquisition IssuesBharatSubramonyNo ratings yet

- PSO Shell Report - Financial ManagementDocument7 pagesPSO Shell Report - Financial ManagementChaudhary Hassan ArainNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Report Honda SP 125Document10 pagesFeasibility Report Honda SP 125chthakorNo ratings yet

- Accounting 202 - CVP AnalysisDocument20 pagesAccounting 202 - CVP Analysisrodell pabloNo ratings yet

- S. Y. B Com - Accounts: Piecemeal Distribution 2016-17Document5 pagesS. Y. B Com - Accounts: Piecemeal Distribution 2016-17Aman VakhariaNo ratings yet

- Macro Econ CH 10Document42 pagesMacro Econ CH 10maria37066100% (1)

- ProblemSet Cash Flow EstimationQA-160611 - 021520Document25 pagesProblemSet Cash Flow EstimationQA-160611 - 021520Jonathan Punnalagan100% (2)

- Chapter 2 The Basics of Supply and Demand Part1Summer2021Document8 pagesChapter 2 The Basics of Supply and Demand Part1Summer2021sarahNo ratings yet

- SWEAT One-PagerDocument1 pageSWEAT One-Pagernmass4workersNo ratings yet

- TEF 1000 NAMES 2019 TEF Partners 1 .01Document7 pagesTEF 1000 NAMES 2019 TEF Partners 1 .01KAMPAMBA LUKWESANo ratings yet

- Blue Energy: Salinity Gradient Power in PracticeDocument8 pagesBlue Energy: Salinity Gradient Power in PracticeHasim BenziniNo ratings yet

- RENCANA ANGGARAN BIAYA PEMASANGAN KACA PROYEK GEDUNG 21 AVENUEDocument5 pagesRENCANA ANGGARAN BIAYA PEMASANGAN KACA PROYEK GEDUNG 21 AVENUEAswal Al-fakirNo ratings yet

- Design School After Boundaries and DisciplinesDocument236 pagesDesign School After Boundaries and DisciplinesOsama AmirNo ratings yet

- Departmental Sked (2nd Semester 2019-2020) - UpdatedDocument80 pagesDepartmental Sked (2nd Semester 2019-2020) - UpdatedKim Kenneth Roca100% (1)

- Handicraft ReportDocument38 pagesHandicraft ReportMohd Danish Hussain0% (1)

- Chapter 1: Worksheet Mark Scheme: (20 Marks)Document2 pagesChapter 1: Worksheet Mark Scheme: (20 Marks)GermanRobertoFongNo ratings yet

- Format of Extra ItemDocument9 pagesFormat of Extra ItemEdison SinghNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Project On Tata SteelDocument18 pagesStrategic Management Project On Tata SteelRonak GosaliaNo ratings yet

- Schloss-10 11 06Document3 pagesSchloss-10 11 06Logic Gate CapitalNo ratings yet

- Kiaer Christina Imagine No Possessions The Socialist Objects of Russian ConstructivismDocument363 pagesKiaer Christina Imagine No Possessions The Socialist Objects of Russian ConstructivismAnalía Capdevila100% (2)

- Absapl-R150-27 06 2023Document1 pageAbsapl-R150-27 06 2023janinepretorius11No ratings yet