Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jimenez vs. Bucoy: Pay To The Equitable Banking Corporation Order of A/C of Casville Enterprises, Inc

Uploaded by

rockaholicnepsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jimenez vs. Bucoy: Pay To The Equitable Banking Corporation Order of A/C of Casville Enterprises, Inc

Uploaded by

rockaholicnepsCopyright:

Available Formats

Jimenez vs.

Bucoy Facts: In the proceedings in the intestate of Luther Young and Pacita Young who died in 1954 and1952, respectively, Pacifica Jimenez presented for payment 4 promissory notes signed by Pacitafor different amounts totalling P21,000. Acknowledging receipt by Pacita during the Japaneseoccupation, in the currency then prevailing, the Administrator manifested willingness to payprovided adjustment of the sums be made in line with the Ballantyne schedule. The claimantobjected to the adjustment insisting on full payment in accordance with the notes. The court heldthat the notes should be paid in the currency prevailing after the war, and thus entitling Jimemezto recover P21,000 plus P2,000 as attorneys fees. Hence, the appeal. Issue: Whether the amounts should be paid, peso for peso; or whether a reduction should bemade in accordance with the Ballantyne schedule.

Held: If the loan was expressly agreed to be payable only after the war, or after liberation, orbecame payable after those dates, no reduction could be effected, and peso-for-peso paymentshall be ordered in Philippine currency. The Ballantyne Conversion Table does not apply where themonetary obligation, under the contract, was not payable during the Japanese occupation.Herein, the debtor undertook to pay six months after the war, peso for peso payment isindicated. Ang Tek Lian vs Court of Appeals Facts: In 1946, Ang Tek Lian approached Lee Hua and asked him if he could give him P4,000.00. He said that he meant to withdraw from the bank but the banks already closed. In exchange, he gave Lee Hua a check which is payable to the order of cash. The next day, Lee Hua presented the check for payment but it was dishonored due to insufficiency of funds. Lee Hua eventually sued Ang Tek Lian. In his defense, Ang Tek Lian argued that he did not indorse the check to Lee Hua and that when the latter accepted the check without Ang tek Lians indorsement, he had done so f ully aware of the risk he was running thereby. ISSUE: Whether or not Ang Tek Lian is correct.

HELD: No. Under the Negotiable Instruments Law (sec. 9 *d+), a check drawn payable to the order of cash is a check payable to bea rer hence a bearer instrument, and the bank may pay it to the person presenting it for payment without th e drawers indorsement. Where a check is made payable to the order of cash, the word cash does not purport to be the name of any person, and hence the instrument is payable to be arer. The drawee bank need not obtain any indorsement of the check, but may pay it to the person presenting it without any indorsement. Equitable Banking Corporation vs Intermediate Appellate Court Facts: In 1975, Liberato Casals, majority stockholder of Casville Enterprises, went to buy two garrett skidders (bulldozers) from Edward J. Nell Company amounting to P970,000.00. To pay the bulldozers, Casals agreed to open a letter of credit with the Equitable Banking Corporation. Pursuant to this, Nell Company shipped one of the bulldozers to Casville. Meanwile, Casville advised Nell Company that in order for the letter of credit to be opened, Casville needs to deposit P427,300.00 with Equitable Bank, and that since Casville is a little short, it requested Nell Company to pay the deposit in the meantime. Nell Company agreed and so it eventually sent a check in the amount of P427,300.00. The check read: Pay to the EQUITABLE BANKING CORPORATION Order of A/C OF CASVILLE ENTERPRISES, INC. Nell Company sent the check to Casville so that it would be the latter who could send it to Equitable Bank to cover the deposit in lieu of the letter of credit. Casals received the check, he went to Equitable Bank, and the teller received the check. The teller, instead of applying the amount as deposit in lieu of the letter of credit, credited the check to Casvilles account with Equitable Bank. Casals later withdrew all the P427,300.00 and appropriated it to himself. ISSUE: Whether or not Equitable Bank is liable to cover for the loss.

HELD: No. The subject check was equivocal and patently ambiguous. Reading on the wordings of the check, the payee thereon ceased to be indicated with reasonable certainty in contravention of Section 8 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. As worded, it could be accepted as deposit to the account of the party named after the symbols A/C, or payable to the Bank as trustee, or as an agent, for Casville Enterprises, Inc., with the latter being the ul timate beneficiary. That ambiguity is to be taken contra proferentem that is, construed against Nell Company who caused the ambiguity and could have also avoided it by the exercise of a little more care. Thus, Article 1377 of the Civil Code, provides: Art. 1377. The interpretation of obscure words or stipulations in a contract shall not favor the party who caused the obscurity. Philippine National Bank vs. Manila Oil Refining & By-Products Company, Inc. [GR L-18103, Facts: On 8 May 1920, the manager and the treasurer of the Manila Oil Refining & By-Products Company, Inc,. executed and delivered to the Philippine National Bank (PNB), a written instrument reading as follows: "RENEWAL. P61,000.00 MANILA, P.I., May 8, 1920. On demand after date we promise to pay to the order of the Philippine National Bank sixty-one thousand only pesos at Philippine National Bank, Manila, P.I. Without defalcation, value received; and do hereby authorize any attorney in the Philippine Islands, in

case this note be not paid at maturity, to appear in my name and confess judgment for the above sum with interest, cost of suit and attorney's fees of ten (10) per cent for collection, a release of all errors and waiver of all rights to inquisition and appeal, and to the benefit of all laws exempting property, real or personal, from levy or sale. Value received. No. Due MANILA OIL REFINING & BY-PRODUCTS CO., INC., (Sgd.) VICENTE SOTELO, Manager. MANILA OIL REFINING & BY-PRODUCTS CO., INC., (Sgd.) RAFAEL LOPEZ. Treasurer. " The Manila Oil Refining & By-Products Company, Inc. failed to pay the promissory note on demand. PNB brought action in the Court of First Instance of Manila, to recover P61,000, the amount of the note, together with interest and costs. Mr. Elias N. Recto, an attorney associated with PNB, entered his appearance in representation of Manila Oil, and filed a motion confessing judgment. Manila Oil, however, in a sworn declaration, objected strongly to the unsolicited representation of attorney Recto. Later, attorney Antonio Gonzalez appeared for Manila Oil and filed a demurrer, and when this was overruled, presented an answer. The trial judge rendered judgment on the motion of attorney Recto in the terms of the complaint. <The disposition of the trial court and the process as to how the case reached the Supreme Court is not in thefacts.> In the Supreme Court, the question of first impression raised in the case concerns the validity in this jurisdiction of a provision in a promissory note whereby in case the same is not paid at maturity, the maker authorizes any attorney to appear and confess judgment thereon for the principal amount, with interest, costs, and attorney's fees, and waives all errors, rights to inquisition, and appeal, and all property exemptions. Issue: Whether the Negotiable Instruments Law (Act No. 2031) expressly recognized judgment notes, enforcible under the regular procedure.

Held: The Negotiable Instruments Law, in section 5, provides that "The negotiable character of an instrument otherwise negotiable is not affected by a provision which (b) Authorizes confession of judgment if the instrument be not paid at maturity"; but this provision of law cannot be taken to sanction judgments by confession, because it is a portion of a uniform law which merely provides that, in jurisdictions where judgments notes are recognized, such clauses shall not affect the negotiable character of the instrument. Moreover, the same section of the Negotiable Instruments Law concludes with these words: "But nothing in this section shall validate any provision or stipulation otherwise illegal." Consolidated Plywood Industries Inc. vs. IFC Leasing and Acceptance Corp. Facts: Consolidated Plywood Industries Inc. (CPII) is a corporation engaged in the logging business. It hadfor its program of logging activities for the year 1978 the opening of additional roads, and simultaneouslogging operations along the route of said roads, in its logging concession area at Baganga, Manay, and Commercial Law Negotiable Instruments Law, 2006 ( 12 )Narratives (Berne Guerrero) Caraga, Davao Oriental. For this purpose, it needed 2 additional units of tractors. Cognizant of CPII's need and purpose, Atlantic Gulf & Pacific Company of Manila, through its sister company and marketing arm, Industrial Products Marketing (IPM), a corporation dealing in tractors and other heavy equipment business, offered to sell to CPII 2 "Used" Allis Crawler Tractors, 1 an HD-21-B and the other an HD-16-B. In order to ascertain the extent of work to which the tractors were to be exposed, and to determine the capability of the "Used" tractors being offered, CPII requested the seller-assignor to inspect the jobsite. After conducting said inspection, IPM assured CPII that the "Used" Allis Crawler Tractors which were being offered were fit for the job, and gave the corresponding warranty of 90 days performance of the machines and availability of parts. With said assurance and warranty, and relying on the IPM's skill and judgment, CPII through Henry Wee and Rodolfo T. Vergara, president and vice-president, respectively, agreed to purchase on installment said 2 units of "Used" Allis Crawler Tractors. It also paid the down payment of P210,000.00. On 5 April 1978, IPM issued the sales invoice for the 2 units of tractors. At the same time, the deed of sale with chattel mortgage with promissory note was executed. Simultaneously with the execution of the deed of sale with chattel mortgage with promissory note, IPM, by means of a deed of assignment, assigned its rights and interest in the chattel mortgage in favor of IFC Leasing and Acceptance Corporation. Immediately thereafter, IPM delivered said 2 units of "Used" tractors to CPII's jobsite and as agreed, IPM stationed its own mechanics to supervise the operations of the machines. Barely 14 days had elapsed after their delivery when one of the tractors broke down and after another 9 days, the other tractor likewise broke down. On 25 April 1978, Vergara formally advised IPM of the fact that the tractors broke down and requested for IPM's usual prompt attention under the warranty. In response to the formal advice by Vergara, IPM sent to the jobsite its mechanics to conduct the necessary repairs, but the tractors did not come out to be what they should be after the repairs were undertaken because the units were no longer serviceable. Because of the breaking down of the tractors, the road building and simultaneous logging operations of CPII were delayed and Vergara advised IPM that the payments of the installments as listed in the promissory note would likewise be delayed until IPM completely fulfills its obligation under its warranty. Since the tractors were no longer serviceable, on 7 April 1979, We asked IPM to pull out the units and have them reconditioned, and thereafter to offer them for sale. The proceeds were to be given to IFC Leasing and the excess, if any, to be divided between IPM and CPII which offered to bear 1/2 of the reconditioning cost. No response to this letter was received by CPII and despite several follow-up calls, IPM did nothing with regard to the request, until the complaint in the case was filed by IFC Leasing against CPII, Wee, and Vergara. The complaint was filed by IFC Leasing against CPII, et al. for the recovery of the principal sum of P1,093,789.71, accrued interest of P151,618.86 as of 15 August 1979, accruing interest there after at the rate of 12% per annum, attorney's fees of P249,081.71 and costs of suit. CPII, et al. filed their amended answer praying for the dismissal of the complaint and asking the trial court to order IFC leasing to pay them damages in an amount at the sound discretion of the court, P20,000.00 as and for attorney's fees, and P5,000.00 for expenses of litigation, among others. In a decision dated 20 April 1981, the trial court rendered judgment, ordering CPII, et al. to pay jointly and severally in their official and personal capacities the principal sum of P1,093,798.71 with accrued interest of P151,618.86 as of 15 August 1979 and accruing interest thereafter at the rate of 12% per annum; and attorney's fees equivalent to 10% of the principal and to pay the costs of the suit. On 8 June 1981, the trial court issued an order denying the motion for reconsideration filed by CPII, et al. CPII, et

al.appealed to the Intermediate Appellate Court. On 17 July 1985, the Intermediate Appellate Court issued the decision affirming in toto the decision of the trial court. CPII et al.'s motion for reconsideration was denied by the Intermediate Appellate Court in its resolution dated 17 October 1985, a copy of which was received by CPII, et al. on 21 October 1985. CPII, et al. filed the petition for certiorari under rule 45 of the Rules of Court. Issue: Whether the promissory note in question is a negotiable instrument.

Held: The pertinent portion of the note provides that ""FOR VALUE RECEIVED, I/we jointly and severally promise to pay to the INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS MARKETING, the sum of ONE MILLION NINETY THREE THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED EIGHTY NINE PESOS & 71/100 only (P1,093,789.71), Philippine Currency, the said principal sum, to be payable in 24 monthly installments starting July 15, 1978 Commercial Law Negotiable Instruments Law, 2006 ( 13 )Narratives (Berne Guerrero) and every 15th of the month thereafter until fully paid." Considering that paragraph (d), Section 1 of the Negotiable Instruments Law requires that a promissory note "must be payable to order or bearer," it cannot be denied that the promissory note in question is not a negotiable instrument. The instrument in order to be considered negotiable must contain the so called "words of negotiability" i.e., must be payable to "order" or "bearer." These words serve as an expression of consent that the instrument may be transferred. This consent is indispensable since a maker assumes greater risk under a negotiable instrument than under a nonnegotiable one. Without the words "or order" or "to the order of," the instrument is payable only to the person designated therein and is therefore non-negotiable. Any subsequent purchaser thereof will not enjoy the advantages of being a holder of a negotiable instrument, but will merely "step into the shoes" of the person designated in the instrument and will thus be open to all defenses available against the latter. Therefore, considering that the subject promissory note is not a negotiable instrument, it follows that IFC Leasing can never be a holder in due course but remains a mere assignee of the note in question. Thus, CPII may raise against IFC Leasing all defenses available to it as against IPM. This being so, there was no need for CPII to implead IPM when it was sued by IFC Leasing because CPII's defenses apply to both or either of them. Government Service Insurance System v. Court of Appeals Facts: Private respondents, Mr. and Mrs. Isabelo R. Racho, together with spouses Mr. and Mrs Flaviano Lagasca, executed a deed of mortgage, dated November 13, 1957, in favor of petitioner GSIS and subsequently, another deed of mortgage, dated April 14, 1958, in connection with two loans granted by the latter in the sums of P 11,500.00 and P 3,000.00, respectively. A parcel of land covered by Transfer Certificate of Title No. 38989 of the Register of Deed of Quezon City, co-owned by said mortgagor spouses, was given as security under the two deeds. They also executed a 'promissory note". On July 11, 1961, the Lagasca spouses executed an instrument denominated "Assumption of Mortgage," obligating themselves to assume the said obligation to the GSIS and to secure the release of the mortgage covering that portion of the land belonging to spouses Racho and which was mortgaged to the GSIS. This undertaking was not fulfilled. Upon failure of the mortgagors to comply with the conditions of the mortgage, particularly the payment of the amortizations due, GSIS extrajudicially foreclosed the mortgage and caused the mortgaged property to be sold at public auction on December 3, 1962. For more than two years, the spouses Racho filed a complaint against the spouses Lagasca praying that the extrajudicial foreclosure "made on, their property and all other documents executed in relation thereto in favor of the Government Service Insurance System" be declared null and void. The trial court rendered judgment on February 25, 1968 dismissing the complaint for failure to establish a cause of action. However, said decision was reversed by the respondent Court of Appeals, stating that, although formally they are co-mortgagors, the GSIS required their consent to the mortgage of the entire parcel of land which was covered with only one certificate of title, with full knowledge that the loans secured were solely for the benefit of the appellant Lagasca spouses who alone applied for the loan. Issues: Whether the respondent court erred in annulling the mortgage as it affected the share of private respondents in the reconveyance of their property? Whether private respondents benefited from the loan, the mortgage and the extrajudicial foreclosure proceedings are valid? Held: Both parties relied on the provisions of Section 29 of Act No. 2031, otherwise known as the Negotiable Instruments Law, which provide that an accommodation party is one who has signed an instrument as maker, drawer, acceptor of indorser without receiving value therefor, but is held liable on the instrument to a holder for value although the latter knew him to be only an accommodation party. The promissory note, as well as the mortgage deeds subject of this case, are clearly not negotiable instruments. These documents do not comply with the fourth requisite to be considered as such under Section 1 of Act No. 2031 because they are neither payable to order nor to bearer. The note is payable to a specified party, the GSIS. Absent the aforesaid requisite, the provisions of Act No. 2031 would not apply; governance shall be afforded, instead, by the provisions of the Civil Code and special laws on mortgages. As earlier indicated, the factual findings of respondent court are that private respondents signed the documents "only to give their consent to the mortgage as required by GSIS", with the latter having full knowledge that the loans secured thereby were solely for the benefit of the Lagasca spouses. Contrary to the holding of the respondent court, it cannot be said that private respondents are without liability under the aforesaid mortgage contracts. The factual context of this case is precisely what is contemplated in the last paragraph of Article 2085 of the Civil Code to the effect that third persons who are not parties to the principal obligation may secure the latter by pledging or mortgaging their own property. So long as valid consent was given, the fact that the loans were solely for the benefit of the Lagasca spouses would not invalidate the mortgage with respect to private respondents' share in the property. The respondent court, erred in annulling the mortgage insofar as it affected the share of private respondents or in directing reconveyance of their property or the payment of the value.

You might also like

- General Banking Law (Case Digest)Document22 pagesGeneral Banking Law (Case Digest)Na AbdurahimNo ratings yet

- CHINA BANK BANKRUPTCY RULINGDocument27 pagesCHINA BANK BANKRUPTCY RULINGAlvin JohnNo ratings yet

- Boundary Dispute Among LGUsDocument13 pagesBoundary Dispute Among LGUsrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- The Effective Use of Written Position Papers in MediationDocument5 pagesThe Effective Use of Written Position Papers in MediationrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- A Short View of the Laws Now Subsisting with Respect to the Powers of the East India Company To Borrow Money under their Seal, and to Incur Debts in the Course of their Trade, by the Purchase of Goods on Credit, and by Freighting Ships or other Mercantile TransactionsFrom EverandA Short View of the Laws Now Subsisting with Respect to the Powers of the East India Company To Borrow Money under their Seal, and to Incur Debts in the Course of their Trade, by the Purchase of Goods on Credit, and by Freighting Ships or other Mercantile TransactionsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

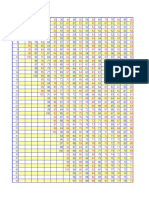

- Transmutation Table For Grade ScoresDocument18 pagesTransmutation Table For Grade Scoresbanglecowboy84% (49)

- Philippine laws on annulment, divorce and legal separationDocument13 pagesPhilippine laws on annulment, divorce and legal separationrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Case DigestDocument6 pagesNegotiable Instruments Case DigestDianne Esidera RosalesNo ratings yet

- Ched CmoDocument222 pagesChed CmoJake Altiyen0% (1)

- NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW DIGESTSDocument22 pagesNEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW DIGESTSDianne Bernadeth Cos-agonNo ratings yet

- PNB Vs Manila Oil Refining, 43 Phil 444, June 8, 1922Document26 pagesPNB Vs Manila Oil Refining, 43 Phil 444, June 8, 1922Galilee RomasantaNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Atty CabochanDocument38 pagesCase Digests Atty CabochanAthena Lajom100% (1)

- BIR Form2305Document1 pageBIR Form2305Gayle Abaya75% (4)

- BIR Form2305Document1 pageBIR Form2305Gayle Abaya75% (4)

- NIL DigestsDocument7 pagesNIL DigestsaugustofficialsNo ratings yet

- Nego Case DigestDocument5 pagesNego Case DigestFaye BuenavistaNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW 1 REVIEWER Padilla Cases and Notes Ortega NotesDocument110 pagesCRIMINAL LAW 1 REVIEWER Padilla Cases and Notes Ortega NotesrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Vdocuments - MX - Case Digests Atty CabochanDocument38 pagesVdocuments - MX - Case Digests Atty CabochanRhuejane Gay MaquilingNo ratings yet

- Nego Digests Watermark Free FINALDocument22 pagesNego Digests Watermark Free FINALAleezah Gertrude RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Prudential Bank Vs IACDocument7 pagesPrudential Bank Vs IAC001nooneNo ratings yet

- TRUST RECEIPT DOCTRINE AND MARGINAL DEPOSIT DEDUCTIONDocument9 pagesTRUST RECEIPT DOCTRINE AND MARGINAL DEPOSIT DEDUCTIONyassercarlomanNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Mercantile LawDocument3 pagesCase Digests Mercantile LawCheryl ChurlNo ratings yet

- Agency Case Digests - Art. 1899-1918 - Atty. Obieta - 2D 2012Document5 pagesAgency Case Digests - Art. 1899-1918 - Atty. Obieta - 2D 2012Albert BantanNo ratings yet

- Natural Obligations and Estoppel (CASE DIGEST)Document3 pagesNatural Obligations and Estoppel (CASE DIGEST)jealousmistress100% (1)

- Prudential Bank v. IacDocument5 pagesPrudential Bank v. IacanailabucaNo ratings yet

- Caltex v Court of Appeals: Certificates of Time Deposits are Negotiable InstrumentsDocument5 pagesCaltex v Court of Appeals: Certificates of Time Deposits are Negotiable InstrumentsIvan SambranoNo ratings yet

- Cases - Negotiable InstrumentsDocument70 pagesCases - Negotiable InstrumentsmisseixihNo ratings yet

- Kauffman vs. PNB, 42 Phil 182, Sept. 29, 1921Document45 pagesKauffman vs. PNB, 42 Phil 182, Sept. 29, 1921Raina Phia PantaleonNo ratings yet

- LowieDocument4 pagesLowieJerry Marc CarbonellNo ratings yet

- First Division: Syllabus SyllabusDocument16 pagesFirst Division: Syllabus SyllabusWendy JubayNo ratings yet

- 3 Power Commercial and Industrial Corp. V.20210424-14-Ew4euuDocument11 pages3 Power Commercial and Industrial Corp. V.20210424-14-Ew4euuShaula FlorestaNo ratings yet

- Court upholds supplier's claim, denies marketing firm's offset demandDocument4 pagesCourt upholds supplier's claim, denies marketing firm's offset demandGericah RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Nego Cases 2Document28 pagesNego Cases 2Jake CastañedaNo ratings yet

- 1 - Power Commercial and Industrial Corp. v. Court of Appeals (1997) PDFDocument10 pages1 - Power Commercial and Industrial Corp. v. Court of Appeals (1997) PDFGeorgina Mia GatoNo ratings yet

- Caltex vs. Court of Appeals ruling on negotiability of CTDsDocument8 pagesCaltex vs. Court of Appeals ruling on negotiability of CTDsHERCEA GABRIELLE CHUNo ratings yet

- Power Commercial and Industrial Corp Vs CADocument11 pagesPower Commercial and Industrial Corp Vs CAPaolo Antonio EscalonaNo ratings yet

- Bañas vs. Asia Pacific Finance Corporation: G.R. No. 128703. October 18, 2000.Document10 pagesBañas vs. Asia Pacific Finance Corporation: G.R. No. 128703. October 18, 2000.Krisha FayeNo ratings yet

- Third Division: Syllabus SyllabusDocument10 pagesThird Division: Syllabus SyllabusEdith OliverosNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Phils.), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, GR No. 97753, Aug. 10, 1992Document5 pagesCaltex (Phils.), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, GR No. 97753, Aug. 10, 1992Mclean BigorniaNo ratings yet

- Caltex (Phils.), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals and Security Bank and Trust Co. G.R. No. 97753, Aug. 10, 1992Document7 pagesCaltex (Phils.), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals and Security Bank and Trust Co. G.R. No. 97753, Aug. 10, 1992firmo minoNo ratings yet

- Mutuum Case DigestsDocument18 pagesMutuum Case DigestsHaidelyn CapistranoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Education Co. Inc. V. Soriano (G.R. No. L-22405. June 30, 1971)Document7 pagesPhilippine Education Co. Inc. V. Soriano (G.R. No. L-22405. June 30, 1971)Ipe DimatulacNo ratings yet

- Judicial Notice: TA Case No. 4897Document13 pagesJudicial Notice: TA Case No. 4897maelynsummerNo ratings yet

- Case Digest NilDocument10 pagesCase Digest NilMarc AcostaNo ratings yet

- NIL Syl Digested CasesDocument20 pagesNIL Syl Digested CasesJerik SolasNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Case Digest: Philippine Airlines V. CA (1990)Document8 pagesNegotiable Instruments Case Digest: Philippine Airlines V. CA (1990)Dagul JauganNo ratings yet

- Spouses Tirso Vintola and Loreta Dy Vs Insular Bank of Asia AndamericaDocument3 pagesSpouses Tirso Vintola and Loreta Dy Vs Insular Bank of Asia Andamericaangelsu04No ratings yet

- Philippine Education CoDocument11 pagesPhilippine Education CoMark Hiro NakagawaNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Bank Vs CADocument5 pagesConsolidated Bank Vs CAMichyLGNo ratings yet

- Obli Cases - TuesdayDocument13 pagesObli Cases - TuesdayMonicaSumangaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest NilDocument9 pagesCase Digest NilyilkkkNo ratings yet

- Replevin With Deficiency ClaimDocument27 pagesReplevin With Deficiency ClaimDeeby PortacionNo ratings yet

- Nego Case 1 16Document4 pagesNego Case 1 16Joseph John Santos RonquilloNo ratings yet

- 109 Phil 706 - Commercial Law - Negotiable Instruments Law - Negotiation After Dishonor - Holder in Due CourseDocument4 pages109 Phil 706 - Commercial Law - Negotiable Instruments Law - Negotiation After Dishonor - Holder in Due CourseBingoheartNo ratings yet

- RCBC Liable as Irregular Endorser Reimburses EmployeeDocument22 pagesRCBC Liable as Irregular Endorser Reimburses EmployeeKria Celestine ManglapusNo ratings yet

- Oblicon CasesDocument35 pagesOblicon CasesNica09_foreverNo ratings yet

- Filinvest Credit Corp vs CA Ruling on Replevin and Good FaithDocument4 pagesFilinvest Credit Corp vs CA Ruling on Replevin and Good FaithLisa BautistaNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank & Trust Company vs. Court of APPEALS, G.R. NO. 88866, FEBRUARY 18, 1991Document3 pagesMetropolitan Bank & Trust Company vs. Court of APPEALS, G.R. NO. 88866, FEBRUARY 18, 1991Michelle AnneNo ratings yet

- NEGO - Casedigest - 1st - 2nd WeekDocument17 pagesNEGO - Casedigest - 1st - 2nd WeekFrancisco MarvinNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court Case Digest on Money Market Transactions and Promissory Note DisputesDocument47 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court Case Digest on Money Market Transactions and Promissory Note DisputesRhena SaranzaNo ratings yet

- Digest Case of PNB Vs Manila Oil Refining and Company Inc.Document2 pagesDigest Case of PNB Vs Manila Oil Refining and Company Inc.Eiram G Lear50% (2)

- 2sr Nego ReyesDocument4 pages2sr Nego ReyesRikka ReyesNo ratings yet

- RFBT MidtermDocument27 pagesRFBT MidtermShane CabinganNo ratings yet

- CTD negotiability and holder in due course statusDocument6 pagesCTD negotiability and holder in due course statusRamos GabeNo ratings yet

- Banas Vs Asia Pacific - GraceDocument3 pagesBanas Vs Asia Pacific - GraceMary Grace G. EscabelNo ratings yet

- Allied Banking Corporation vs. OrdoñezDocument13 pagesAllied Banking Corporation vs. Ordoñezcncrned_ctzenNo ratings yet

- Philippine British Assurance Co. vs. IACDocument7 pagesPhilippine British Assurance Co. vs. IACAnonymous fL9dwyfekNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Bank vs. Court of AppealsDocument8 pagesMetropolitan Bank vs. Court of AppealsSteve SmithNo ratings yet

- MGB29-13 Quarterly Report PSI - CSAGDocument3 pagesMGB29-13 Quarterly Report PSI - CSAGrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- 1701Q Jan 2018 Final Rev2Document2 pages1701Q Jan 2018 Final Rev2Balot EspinaNo ratings yet

- InnovaDocument3 pagesInnovarockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Impact of Balog-Balog Project on environment and residentsDocument2 pagesImpact of Balog-Balog Project on environment and residentsrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Finance I Preliminary Examination: I. Definition. Define The FollowingDocument1 pageFinance I Preliminary Examination: I. Definition. Define The FollowingrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Eco I Preliminary Examination: I. Multiple Choice. Choose The Best AnswerDocument1 pageEco I Preliminary Examination: I. Multiple Choice. Choose The Best AnswerrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Accounting Part IDocument2 pagesFundamentals of Accounting Part IrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Total Quality ManagementDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Total Quality ManagementrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Accountants Letter 7-1-10-1Document2 pagesAccountants Letter 7-1-10-1api-236106798No ratings yet

- SAN JUAN DE LETRAN MATH 117 COURSE SYLLABUSDocument8 pagesSAN JUAN DE LETRAN MATH 117 COURSE SYLLABUSrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Pricelist Sept16 2013Document1 pagePricelist Sept16 2013rockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- (Batas Pambansa Blg. 68) : Title I General ProvisionsDocument53 pages(Batas Pambansa Blg. 68) : Title I General ProvisionsrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Cyber Crime Ringleader Sentenced To Five Years in PrisonDocument2 pagesCyber Crime Ringleader Sentenced To Five Years in PrisonrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Labor Code of The Philippines - DOLEDocument65 pagesLabor Code of The Philippines - DOLENoel PerenaNo ratings yet

- CH 11Document26 pagesCH 11rockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Jimenez vs. Bucoy: Pay To The Equitable Banking Corporation Order of A/C of Casville Enterprises, IncDocument3 pagesJimenez vs. Bucoy: Pay To The Equitable Banking Corporation Order of A/C of Casville Enterprises, IncrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- TranspoDocument24 pagesTransposcsurferNo ratings yet

- TranspoDocument24 pagesTransposcsurferNo ratings yet

- Impeachment of Philippine Chief Justice Renato CoronaDocument34 pagesImpeachment of Philippine Chief Justice Renato CoronarockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Impeachment of Philippine Chief Justice Renato CoronaDocument34 pagesImpeachment of Philippine Chief Justice Renato CoronarockaholicnepsNo ratings yet

- Guesing GamesDocument2 pagesGuesing GamesrockaholicnepsNo ratings yet