Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jep 1748

Uploaded by

Pier Paolo Dal MonteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jep 1748

Uploaded by

Pier Paolo Dal MonteCopyright:

Available Formats

jep_1748

Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice ISSN 1365-2753

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

EDITORIAL

Virtue, progress and practice

jep_1748

1..9

Michael Loughlin PhD,1 Robyn Bluhm PhD,2 Stephen Buetow PhD,3 Ross E. G. Upshur MD MA MSc CCFP FRCPC,4 Maya J. Goldenberg PhD,5 Kirstin Borgerson MA PhD6 and Vikki Entwistle PhD7

1 2

Reader in Applied Philosophy, Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, MMU Cheshire, Crewe, UK Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA 3 Associate Professor, Department of General Practice, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 4 Director, University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics, Toronto, ON, Canada 5 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada 6 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada 7 Professor of Values in Health Care, Associate Director, Social Dimensions of Health Institute, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK

Keywords autonomy, certainty/uncertainty, criticism, emotion, empiricism, epistemology, ethics, evidence, evidence-based medicine, good practice, judgement, justication, medical imperialism, medical paternalism, methodology, person-centred medicine, philosophy, professionalism, progress, rationality, reasoning, science, tacit knowledge, values, values-based practice, virtue

Correspondence Dr Michael Loughlin Department of Interdisciplinary Studies MMU Cheshire Crewe CW1 5DU UK E-mail: m.loughlin@mmu.ac.uk

Accepted for publication: 14 July 2011 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01748.x

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man. (G.B. Shaw) [1] There are questions so resistant to easy resolution that we tend to ignore them for as long as we can, but so fundamental that they keep returning whenever we try to discuss anything that really matters with any degree of seriousness. Such questions are often deemed philosophical in nature,1 and questions of this sort in clinical practice include: what is good practice in medicine and health care? What do we mean by progress in these areas? How do we recognize virtue when we see it? How do we support and promote it? How do I become a more virtuous practitioner? One problem with these questions is that we do not know precisely how to go about resolving them. We lack a clear and agreed method for producing answers that all rational parties will accept, and that are sufciently full and detailed to be of any practical use meaning, answers that can guide our decisions in specic cases. We can translate this problem into yet another question, but it is similarly philosophical in form: in terms of which methods, and with recourse to which sources of knowledge and evidence, can we aspire, rationally to reach sound conclusions on the nature of progress, virtue and good practice? This further, methodological question cannot credibly be avoided. It would be bizarre indeed if empirical evidence had no bearing on these vital questions, but how precisely we use

1

For a fuller account of the nature of philosophical inquiry, we refer the reader to this journals rst thematic edition on philosophy as applied to medicine and health care [11].

evidence to answer them, and which evidence we use, is by no means obvious. It is not as though there were some missing piece of information that we could one day just nd, that would reveal the answers in much the same manner as Douglas Adamss imagined Deep Thought computer revealing that the answer to the question what is the meaning of life, the universe and everything? was in fact 42 [2]. Certainly, there are texts, articles and published guidelines telling us how to practice more ethically [3,4], use evidence more effectively [5,6] and frame policies that will guarantee that quality and excellence become the hallmarks of our respective organizations [7,8]. Unfortunately, such guidelines, handbooks and how-to texts rarely have anything to say that is at once substantive (that goes beyond the platitudinous) and is also supported by a clear and rigorous account of the reasoning linking their premises to their conclusions [4,6,9,10]. Authors purporting to offer practical advice too often recognize no requirement to supply convincing, explicit argumentation in support of the conclusions they invite their readers to accept [8,11] and are likely to regard the request for supporting arguments as unreasonable. Like the Deep Thought computer, they supply an answer, but not the working out. Their background assumptions and underlying conceptual framework the implicit premises and normative structures that shaped their answers, that determined these answers as opposed to other possible ones are apparently not worth discussing, of no interest to busy practitioners [5] and those employed in the more mundane processes of what is called real life [12]. The current climate is, and has for some time been, one of moderate anti-intellectualism [11]. It is considered reasonable for human beings at least, those deemed responsible professionals to apply their intellectual capacities to the learning of sometimes

1

1 1 2 2

56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice

jep_1748

Editorial

M. Loughlin et al.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59

complex techniques, to know and follow conventions for good practice in their areas of work: how-to questions are the legitimate preoccupations of the rational, professional mind. But it is deemed intellectual in a derisory sense somehow strange, bolshy or other worldly [5,12] for a professional to want to understand the reasons behind the current conventions and to contribute to the debate about their appropriateness and sustainability. The characteristically philosophical attitude, once thought denitive of the professional outlook [11], of asking why? questions why does that follow? why these goals, rules and assumptions as opposed to others? is met with suspicion in many contemporary organizations [1316]. Far from being genuinely unreasonable, such an attitude is, as Shaw notes [1], a permanent prerequisite for progress. The point of Adamss Deep Thought story is not simply the absurdity of hoping to answer questions that are in fact philosophical in nature with recourse to a quasi-scientic calculation. There is an inherent absurdity in the idea of simply accepting an answer on a fundamental matter relevant to the conduct of ones own life, while showing no desire to scrutinize or even comprehend the thinking behind it. Such an answer is in an obvious sense meaningless to those who purport to just accept or work with it, in much the same way that 42 is meaningless as an answer to the question what is the meaning of life, the universe and everything? To practice on the basis of an answer one has no real understanding of is, in just as obvious a way, to act thoughtlessly. Whatever we mean by a rational, responsible practitioner, the person who never thought of thinking for himself at all [11] would not seem to be it. We need to think carefully and for ourselves about how to formulate the questions, and about the types of argument we might employ to address them. We cannot rule out the possibility (and indeed there are strong arguments in favour of the view) that doing the working out with regard to such fundamental matters is part and parcel of being a virtuous practitioner, and that only a community made up of such persons can make real progress [1,8,11]. Fortunately, despite anti-intellectual inuences and the (truly unreasonable) pressures upon practitioners time and energy in the contemporary world [17], there are still many unreasonable men and women who want to understand and control their practices, to question the basis for their activities and who are prepared to subject dominant ideas and assumptions to critical scrutiny. The pages of this journal have for many years supplied ample illustration of the fact that penetrating, intellectually serious discussion of pressing questions facing researchers, clinicians and policy makers is not only possible but necessary, if we are to secure improvements and avoid the pitfalls of dogmatism and the spurious triumphalism that has characterized much of the mainstream debate about progress, evidence, policy and practice in medicine and health care [1824]. In 2010, the journal presented its rst ever philosophy thematic edition, including papers by some of the most original and incisive thinkers; the discipline has to offer on a vast range of subjects of urgent practical import [11]. This, the second thematic edition of the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice to focus specically on the application of philosophical methods and argumentation to medicine and health care, provides an even greater range of papers [2560] on the themes of progress in medicine, virtue in practice, and evidence and methodology in research and evaluation. Articles bring fresh and challenging

2

analyses of the relationship between progress in the science and the practice of medicine, the role and limitations of statistical reasoning in medical research, patient involvement, autonomy and rationality, the relationship between reason and emotional engagement in the life of the good practitioner, the role and value of uncertainty in health care and how to promote virtue in practice. Authors raise urgent methodological and epistemological questions about cultural bias in the generation of evidence and its implications for technological and scientic advances in medicine; medical knowledge and reductionism; epistemic biases in the researching of patient involvement in health care practices; the relationship between experience, narrative and evidence in the formation of arguments with practical conclusions; person-centred and patient-centred approaches to medicine and the increasingly important role of medical humanities in developing new conceptions of practice and new directions in medical research. The edition incorporates a section on empirical research and philosophy, which includes articles and commentaries on the nature and status of tacit knowledge, virtuous actions and practice, evidence-based decision making and the relationship between context and good practice. In addition, there is a section on valuesbased practice (VBP); a debates section incorporating responses to articles in the previous philosophy thematic [on questions as divergent as the relationship between evidence-based medicine (EBM) and the philosophy of science, the epistemic claims of homeopathic practitioners and the ethics of conscience clauses for practitioners in the issue of referrals for abortion]; detailed, critical reviews of two extremely signicant new publications on statistical research and EBM, and a conference report. A key goal of the philosophy thematic edition is to promote interdisciplinary discussion, between philosophy and allied humanities disciplines on the one hand and medical practitioners and researchers on the other. The report on the workshops in the philosophy of medicine and health care at Kings College, London, is a ne illustration of the mutually benecial nature of such interdisciplinary dialogue [60]. Part of our goal is to show not only that philosophy (along with allied humanities disciplines) has an indispensible contribution to make to the discussion of practice, but that the problems of practice provide the proper context for real progress in philosophy. The idea that proper philosophy is somehow detached from the mundane concerns of ordinary life is an aberration, and the philosophers of today need to relearn the skills of Socrates in engaging, attentively, with the claims and the thinking of the broader populace, in particular those engaged in practices vital to our collective well-being. Applied philosophy is not an offshoot of the subject but a return to its roots, in the rigorous questioning and systematic analysis of human thought about the concerns we face in the processes of real life. The attempt to address these concerns helps us to think more carefully about what philosophy is, to challenge and rene our ideas about proper methodology in the subject [8].

60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111

Progress

The edition opens with a series of original papers on the nature of progress in medicine. We can perhaps agree easily enough that progress in medicine is signicantly associated with progress in the biological sciences and in clinical research, but determining the nature of the relationship and its implications for practice is

112 113 114 115 116 117

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

jep_1748

M. Loughlin et al.

Editorial

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59

less straightforward. While we may have a good intuitive sense of what we mean by progress in science, agreeing a formal account that can settle real controversies has proved a more challenging prospect [16,6166] and even if we had a shared account of progress in science, this may not translate easily into a shared conception of progress in medical practice [59,6769]. Jeremy Simon achieves an impressive balance of accessibility and intellectual weight in a fascinating paper, introducing readers to underlying theoretical arguments about the metaphysics of medicine, and of diseases in particular [25]. Simon presents a new account of the nature of diseases, by appealing to the most persuasive features of rival realist and constructivist positions in the philosophy of science, and an insight into what progress in medicine looks like if we understand diseases in this way. Another insightful contribution, that of Leen De Vreese [26], takes as its starting point the important distinction between what scientic progress means for a particular domain, such as medicine, and the question of scientic progress in general. The paper rigorously outlines the methodological differences this distinction implies, based on the goals of the distinct areas being subjected to analysis, and applies these arguments to the proper goals of research in the medical sciences and to EBM in particular showing how critically thinking about EBM from the point of view of progress can help us to put its favoured methodologies in the right perspective [26]. Approaching the issue of progress in medicine from a radically different angle, Ignaas Devisch looks at the debate about autonomy in medicine, and a traditional way of construing that debate that equates autonomy with progress and its opposite, heteronomy the determination of behaviour by outside inuences with (an implicitly regressive) medical paternalism [27]. With detailed reference to the debate about why autonomous people make unhealthy choices, Devisch demonstrates that debates about progress that appeal to such oppositions are based on unrealistic conceptions of choice and the human condition, proposing instead the concepts of oughtonomy and nudging as the basis for solutions to the problems inherent in inuencing individual health choices without being offensively paternalistic [27]. James Penstons work [28,70] presents a signicant and comprehensive challenge to contemporary orthodoxy regarding rationality and progress. It addresses reasoning and progress in medicine specically, but has implications for the way we discuss policy and practice that extend far beyond this area. His contribution to this edition [28] outlines his attack on statistical methods in medical research, in particular the use of epidemiological studies and large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Presenting arguments which he recognizes will be regarded by many as heretical, he questions the benets of these methods and attacks the products of what some regard as the very paradigm of modern medical research as a pig in a poke. (These rigorous and important arguments, and their implications for the future direction of medical research, are taken up again in the reviews section of this edition [58] by an author whose own rather different views on statistical research [71] are similarly subjected to incisive critical attention [59].) The section concludes with a provocative and challenging discussion of EBM and epistemological imperialism [29]. Helen Crowther et al. provide the powerful illustration of haematology to raise serious concerns about the claims of EBM to provide a

method for determining the safety and efcacy of medical therapies and public health interventions. Drawing on research which suggests that EBM may be riven through with cultural bias, both in the generation of evidence and in its translation, the authors argue that technological and scientic advances in medicine accentuate and entrench these cultural biases, to the extent that they may invalidate the evidence we have about disease and its treatment. They note that this creates a signicant ethical, epistemological and ontological challenge for medicine and our thinking about medical progress.

60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70

Virtue

Populist contributions to the debate about rationality and professional practice accept implicitly certain contemporary dichotomies, most obviously between reason and emotion, and as a consequence are likely to dismiss traditional conceptions of virtue as outdated and irrelevant to our modern (or indeed post-modern [47]) world. Our intellectual forefathers were by no means ignorant of the distinction between reason and emotion, but had the wisdom to regard reasoning as an activity of the whole person, a human organism with dispositions and attachments, engaged in the project of making sense of the world and capable of functioning more or less well with respect to others [8,67,72]. They may, perhaps, have been better placed than some contemporary commentators to appreciate the signicance of the fact that practitioners are persons, and that the clinical encounter is an encounter between persons [73]. Discussion of the virtues the dispositions and responses relevant to functioning well as a whole person in a given social context provides not only a realistic approach to discussing good practice. A consideration of virtue also restores the idea of judgement to a central place in this discussion, its having been displaced to the sidelines and relegated to something akin to opinion a form of low-grade evidence in some contemporary quarters [74]. Stephen Buetow notes that in the current intellectual climate, uncertainty is more likely to be cast as a problem for evidencebased care to minimize than as a virtue. But viewed from the perspective that practice is a human activity, certainty is frequently unrealistic and unwise while uncertainty, he argues, is often natural and wise, promoting hope, creativity and a critical attitude, nurturing safety and protecting against excess [30]. Bolstering his argument with reference to Karl Poppers work on fallibilism in the philosophy of science [75], he argues refreshingly for a discussion of uncertainty that is open and positive, treating it and the fact that practitioners are persons as something to highlight, not as some regrettable if ineliminable aw. A stimulating and important paper by James Marcum examines the role of the compound virtue, of prudent love in the practice of clinical medicine [31]. Explaining the conceptual links between the ideas of the wise person, the wise action and the virtuous practitioner, Marcum argues convincingly for the need to incorporate the ethical and intellectual virtues into the medical curriculum, defending the virtues approach against other possible positions in moral epistemology and outlining methods of teaching virtue to create environments that cultivate professional virtue in our schools and practice settings. The ideas of both Marcum and Buetow are nicely complemented by the highly inventive approach of Petra Gelhaus, whose

3

71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

jep_1748

Editorial

M. Loughlin et al.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58

paper on Robot Decisions utilizes the science ction of Isaac Asimov to highlight the role of human emotions in rational decision making, contrasting even the best-designed infallibly ruleoriented robot doctor to the sort of human agency required for virtuous practice in a complex and often inherently uncertain world. Her work brings out the indispensible nature of the emotional virtues in any credible account of rational human agency and thus in any defensible notion of good practice [32]. In a tightly argued and much needed paper on the application of virtue ethics to public health policy, Karen Meagher cautions against the tendency in contemporary bioethics research to develop distinct branches of ethics, as though curative medicine and public health were incompatible domains governed by different ethical paradigms [33]. She shows that the agent-centred approach of virtue ethics offers a different point of entry to the problems faced by public health professionals than more standard, action-centred approaches, and offers insightful criticisms of the tendency to assess the ethics of policy formation as though in a vacuum from any thoughts about the moral character of those framing and acting upon the policies. In the nal paper in this section, Stephen Buetow and Vikki Entwistle point out that the pay for performance schemes that are used in many health systems with the intention of improving and rewarding good-quality care downplay and potentially undermine the value of virtue in clinicians [34]. Buetow and Entwistle acknowledge the difculties of assessing and rewarding good character, but offer some concrete proposals for keeping virtuous practice on the agenda in the context of attempts to develop policies and organizational systems that reward good clinical practice. They speculate that paying for virtue in the short term could ultimately strengthen the intrinsic motivation of clinicians for good practice.

Methodology, argument and evidence in research and practice

As noted in our opening comments, the question of how, precisely, to approach the debate about the fundamental questions of progress, virtue and good practice is itself philosophically contentious. How should we go about applying philosophical analyses of knowledge, reason and good practice to these substantive controversies? What is the right underlying conceptual framework for guiding practice and evaluating policy? How do we frame the questions so that we can go about nding the right answers? Derek Mitchell [35] employs ideas from four diverse thinkers: Martin Heidegger, W.G. Sebald, Gaston Bachelard and HansGeorg Gadamer, to argue for the importance of a broadly antireductionist perspective to understanding knowledge in clinical practice. In this essay, he selects suggestive metaphors for knowing that he argues more adequately ground the encounter between patient and practitioner. He suggests that these authors can help to illuminate the tacit dimensions of knowing relevant to clinical practice. In the accompanying commentary [36], Ross Upshur endorses the need for such perspectives from the humanities, and calls on humanities scholars to provide means to include such ideas in clinical teaching. Sara Donetto and Alan Cribb conduct an extensive review of the literature on patient involvement [37], noting that the framework

4

or methodological lens dominant in much involvement research shaping how research questions are framed, how research is conducted and its ndings interpreted contains an epistemic bias. They argue that this biomedical framework tends to normalize and arguably trivialize intrinsically problematic and contentious concepts such as patient preferences and, at the same time, to obscure the full range of possibilities for reciprocity in the exchanges between the medical world of the professional and the experiential and narrative world of the patient. Richer conceptualizations of collaboration in clinical work are both possible and very much needed, and the authors call for more attention to the idea of epistemic involvement and much greater crossfertilization between different epistemological paradigms in this area of research. In a paper that complements these concerns, Leah McClimans et al. note the lack of a coherent theoretical framework for discussions of patient-centred care, and the subsequent compatibility of the rhetoric of patient-centred care with distinct, mutually incompatible agendas and construals of proper policy and practice in health care. Examining two accounts of patient-centredness in the context of both US and UK health policy, they argue that neither takes seriously the inherently moral nature of such terms as respect and dignity, and they argue for the need for a more rigorous application of clinical ethics in the theoretical justication of patient-centred care [38]. Recent trends in medicine have emphasized the importance of RCTs, in part because they allow information to be gathered from a much broader range of patients than individual physicians can see in the course of their practice. By contrast, anecdotes, including the stories of individual patients, are held to provide a much lower form of evidence. Robin Nunn [39] sets this received wisdom on its head, pointing out that RCTs, too, are stories and that, in fact all types of evidence are ultimately narratives. He provides a thoughtful examination of what stories are, and what purposes they can serve in clinical research and practice, arguing for the importance of mere anecdote. The section concludes with the timely and important contribution of Jane Macnaughton, writing on the challenge medical humanities presents to medicine [40]. In line with other contributions in this section [37,38], Macnaughton notes the constraints that dominant medical conceptual frameworks, heavily inuenced by the historical dominance of logical positivism, have placed upon the discussion of medical practice. Utilizing approaches based on phenomenology and pragmatism, and illustrated with compelling narrative accounts of the reality of illness, the author argues persuasively for a much broader epistemological perspective in our understanding of medicine, one that can help practitioners and patients by appealing to the rich and diverse sources of knowledge that form our intellectual heritage.

59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108

Empirical philosophy? Research evidence, epistemology and ethics

What is the role of empirical data in philosophical debate? On the one hand, philosophical work that is oblivious to evidence and the facts is unlikely to make a serious contribution to any substantial enquiry [8,9,48]. On the other hand, there are compelling logical considerations which suggest that philosophical questions cannot be settled by appeal to the evidence at least, if we mean by

109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

jep_1748

M. Loughlin et al.

Editorial

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59

evidence the discoveries of empirical research. The most famous arguments on this point are in the eld of ethics [76], but similar problems apply to deducing epistemological conclusions from factual data [8]. Arguably, the sciences seek to give us adequate descriptions of the world2 and the term sciences here includes social sciences and psychology, which seek to give us descriptions of the social world and the human psyche. Philosophical enquiry is, in contrast, typically normative in nature [48], addressing in a very immediate way questions phrased most appropriately in the rst person: what should I/we think about issue X? The question of what people in a given time or place do, as a matter of fact, think is part of the subject matter of psychology, but no amount of knowledge about this question can tell us what we should think about the matter. Even Shaws reasonable man needs to adopt some normative framework the belief that I should believe whatever most people in my time and place believe is not an empirical but a normative belief. So while it is widely accepted that empirical research should inform the philosophical process, how precisely its discoveries should inform philosophy remains a contentious issue, as illustrated by the exchanges in this section. The section contains original papers that adopt an empirical approach to philosophical questions, plus commissioned commentaries addressing methodological questions raised by this approach. Stephen Henry et al. examine the relationship between tacit clues and clinical judgement, presenting a qualitative analysis of video elicitation interview transcripts to explore whether physicians and patients identify information likely to be tacit clues or judgments based on tacit clues during health maintenance exams [41]. The article develops ideas and arguments presented in the previous thematic philosophy issue, where Henry applied Polanyis theory of tacit knowing to the clinical context [73]. Two commentaries explore the philosophical implications and presuppositions of the exercise, about the nature of tacit knowledge and clinical judgement. Hillel Braude welcomes what he regards as a timely and relatively novel contribution to a challenging task, that of providing a concrete evaluation of tacit knowing in the doctor patient encounter. This task involves translating the unspeciable in clinical practice into rational terms, thus distinguishing tacit clues from what may otherwise be deemed magical or mystical [42]. Phil Hutchinson and Rupert Read take a more sceptical view [43]. Referring to a commentary in the previous philosophy thematic [72] on Henrys paper in the same issue [73], they note that this commentary, while broadly sympathetic, did have some misgivings which they feel have been ignored by the authors of the study [41]. On the one hand, there is an important, epistemologically and scientically credible usage of the concept of tacit knowledge which takes seriously the implications of human embodiment for knowledge in practice, while on the other there is a usage which trades in a sort of mysticism [43]. In contrast to Braude, these critics do not feel that Henry et al. have entirely expunged all trace of the more mystical version of the term. Furthermore, they argue that the move from tacit knowledge to tacit clues is far more problematic than Henry and colleagues acknowledge [43].

2

This is not to suggest that the activity of nding adequate descriptions is in any way a simple or unproblematic matter. The quest for an adequate description is not theoretically neutral, and in most interesting areas of science will be, at least potentially, philosophically contentious [6,8].

They conclude by noting that the conceptual framework employed by the study colours the presentation of its ndings, such that the philosophical issues are not addressed by work of this sort [43]. Both commentaries use the study as a starting point for some very sophisticated argumentation on the philosophical matter, so while Henry and his colleagues may not have settled the underlying questions,3 their empirical work has generated much in terms of philosophical controversy and analysis perhaps conrming our earlier comments that attention to practice can provide a fertile ground for serious philosophical inquiry. Miles Little and colleagues (Jill Gordon, Pippa Markham, Lucie Rychetnik and Ian Kerridge) conducted a study involving 19 medical practitioners associated with the Sydney Medical School, using semi-structured narrative interviews [44]. The goals of the study were to examine the nature, scope and signicance of virtues in the biographies of medical practitioners and to determine what kind of virtues are at play in their ethical behaviour and reection. Narrative data were analysed using dialectical empiricism, constant comparison and iterative reformulation of research questions. They conclude that a particular version of virtue ethics emerged as the most natural ethical approach for practitioners in the study. Gideon Calders commentary [45] looks at why work of this sort, which combines a case study with direct consideration of normative ethics (so bridging the gap between empirical and theoretical work) is still quite rare. He notes both the need for social science to take normativity properly into account, if it is to furnish us with an adequate understanding of everyday interactions, and for normative ethics to base its reasoning less on articial thought experiments, and more how people actually do make decisions when pondering how we might best make them concluding that bridging the gap should be a priority for both social science and philosophy. He does, however, outline some important concerns about the authors interpretation of interview data, its relation to the specic conclusions reached and the consideration of alternative ethical models in the process of corroborating the virtue-based approach. Mona Gupta conducted in-depth interviews with scholars involved in the development of EBM to uncover its ethical goals [46]. While she notes that EBM is frequently portrayed as a value-free approach to knowing what kinds of treatment really work, there are implicit ethical imperatives contained within this characterization, and her work explores the extent to which EBMs protagonists are committed to the values of improving health outcomes and informed consent, particularly in cases where (on any natural reading) these goals may conict. Peter Duncan and Anne Stephenson report on a small-scale qualitative study, which sought to explore questions with a number of health care professionals and academics about the nature of the good practitioner [47]. A number of themes emerged, including the difculty in discussing this core idea, the role of systems and contexts in this area and the place of consultation and diagnosis in conceptions of good practice. Michael Loughlin questions what precisely this sort of study tells us and how it can be used to develop answers to practical questions, concerning what we should think about the subject matter participants discuss [48]. One distinguishing feature of this

3

And it is fair to point out that they would not claim to have done this.

60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

jep_1748

Editorial

M. Loughlin et al.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58

work is that analysts must be prepared not only to describe but to criticize the responses of participants if the study is to be of philosophical value, while in other types of empirical study, the idea of criticizing or objecting to the data has no legitimate role and indeed makes very little sense. The paper comments primarily on Duncan and Stephenson [47] but also offers an appraisal of the other papers in this section [4146] and raises fundamental methodological questions about the still embryonic discipline of empirically informed philosophy.

the proper role of philosophy, that of bringing to consciousness and challenging underlying commitments and frameworks.4

59 60 61

Debate

The debates section contains responses to articles published in the previous philosophy thematic, opening with a debate between Piersante Sestini and Maya Goldenberg on epistemology, ethics and EBM. In their previous exchange, Sestini tried to parallel EBM and Karl Poppers philosophy of science insofar as the former upholds the demarcation of science and sciences democratic ethos [77]. Goldenberg objected that EBM does not encourage this kind of critical questioning and investigation (and she lamented this failure) [78]. In this volume, Sestini responds to Goldenberg, objecting to her reading of the evidence-based movement as failing to comply with the open-ended, creative and critical scientic inquiry that Popper identies with good scientic practice [54]. In the end, Goldenberg highlights the theme of empirical research already featured prominently in this volume, as she encourages research into the important question whether or not EBM promotes the kind of critical attitude and open-ended knowledge pursuit that any scientic discipline ought to be promoting [55]. Demian Whiting [56] responds to Daniel Hills paper on abortion and referrals for abortion [79]. Hill argued that it is unacceptable for British law to allow doctors to refuse to terminate nonemergency pregnancies but not to refuse to refer for abortion, given that many doctors who are opposed to non-emergency abortion will be opposed also to any action that aids or abets nonemergency abortion, including the action of referral [79]. In reply, Whiting argues that Hill fails to describe properly the correct function of the law, which is not principally about allowing people to exercise moral consistency in their behaviours [56]. Scott Sehon and Donald Stanley continue the debate about homeopathy, in a robust response to the inuential homeopath Peter Fisher, provocatively entitled Taking Procrustes Axe to Professor Fishers response [57]. These authors had previously evoked a version of the simplicity principle to argue that basic philosophical commitments, shared by proponents of homeopathy, should lead us to reject homeopathy [63]. In reply, Fisher noted that what Sehon and Stanley call the simplicity principle is sometimes referred to as Ockhams Razor, the view that we should choose the simplest explanation for the observed facts [64]. His response likened their position instead to Procrustes Axe, which ignores observations that do not conform to simplistic explanations. In this, further response, the authors argue that their use of the principle is neither ad hoc nor invented simply to deal with homeopathy, but that it in fact conforms to established thinking in the philosophy of science, and that Fisher treats as biases what are in fact ideas central to all credible scientic thinking [57].

62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108

Values-based practice

Similar methodological questions to those raised about empirical philosophy concerning the relationship between obtaining information concerning the values of patients, professionals and other, specied groups (on the one hand) and forming conclusions about controversial evaluative questions regarding practice and policy (on the other) are raised by the section on values-based practice. Like EBM, VBP is sometimes characterized as a movement with something important to say about the proper basis for practice. A leading gure in the movement is Bill Fulford, and he describes VBP as a skills-based approach to working more effectively with complex and conicting values, noting its origins as a practical spin-off from the philosophy of psychiatry with applications in the eld of mental health and related primary care, but arguing that it has the potential for a much wider application in health and social care [49]. He is keen to emphasize its compatibility with EBM and discusses the challenges in combining these two approaches. For Tim Thornton, the most intellectually exciting and practically challenging features of VBP are to be found in its denial of two attractive and traditional views of medicine: that diagnosis is a merely factual matter and that the values that should guide treatment and management can be codied in principles [50]. He provides a powerful defence of these features of VBP, but he is far more sceptical about what he regards as a third denitive feature of the approach: a radical liberal view, that right or good outcome should be replaced by right process. Responding to Fulfords claims about the relationship between VBP, EBM and bioethics, Mona Gupta argues that VBP can serve a valuable role in agging areas of moral concern that are often neglected in mainstream values or ethics discourse, but that as a framework for reection and action, VBP does not distinguish itself sufciently from other approaches, including ones that it criticizes [51]. With detailed reference to Fulfords paper, Bob Brecher argues that Fulfords account of what he takes values to be is dangerously unclear and that he glosses over the crucial question of whose values VBP consists in [52]. These features make the approach open to ideological interpretations, making VBP a potential vehicle for neoliberal ideology and a rationale for resolving conicts of value in favour of those who hold power in the current political order. Phil Hutchinson notes that VBP (at least, as presented by Fulford) shares with EBM underlying philosophical assumptions that lead it to be presented as a value-neutral set of procedures, when in fact, he argues, it is based in a specic and contentious approach to value, founded in liberal political philosophy [53]. As a consequence, it risks functioning as a cover for underlying philosophical commitments, rather than playing what he regards as

6

Book reviews and conference report

The edition contains two detailed reviews of important contemporary texts on statistical reasoning and EBM, by critics who are

4

109 110 111 112 113 114 115

Professor Fulford has promised to reply to all of these criticisms in the next philosophy thematic edition of the Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice.

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

jep_1748

M. Loughlin et al.

Editorial

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59

themselves inuential contributors to the eld. James Penstons Stats.Con [70] presents a major intellectual challenge to the use of statistical methods in medical research, in particular the use of epidemiological studies and large-scale RCTs. In a comprehensive and balanced review, Jeremy Howick acknowledges the force and signicance of Penstons arguments, but notes that we do need a coherent account of the proper use of statistical reasoning in practice, and that Penstons work does not spell out any alternatives in detail [58]. Howicks own presentation of The Philosophy of EvidenceBased Medicine [71] is given the characteristically thorough attention of Mark Tonelli, whose commentary on the text provides both a detailed reconstruction of the main arguments and a full critical response [59]. Tonelli welcomes Howicks intellectually serious approach to the subject matter and his evident willingness to engage with signicant philosophical criticisms of EBM presented over many years, and too often ignored by EBM protagonists. However, he argues for the need to go further if Howick is to present a coherent philosophy of medicine. We look forward to the continuation of this important debate, and join Tonelli in welcoming the philosophically serious nature of recent contributions to the topic. The edition closes with a report authored by Elselijn Kingma et al. on the interdisciplinary workshop on concepts of health and disease at the Kings College Centre for the Humanities and Health [60]. As the reader will note, these discussions are inherently valuable for the high quality of debate they provoke on matters of intellectual and practical signicance. They are also valuable for their role in promoting interdisciplinary dialogue including medical professionals and philosophers. We wish these continuing events every success, as this is just the sort of dialogue that we have been arguing, for some years now, is urgently needed so that practice can be better informed by an understanding of its own conceptual basis and so that academics can ground their thinking in a profound engagement with some of the most important realities of contemporary life.

References

1. Shaw, G. B. (1948) Man and Superman. London: Penguin Books. 2. Adams, D. (1992) The Hitch-Hikers Guide to the Galaxy: A Trilogy in Four Parts. London: Pan Books. 3. Kottow, M. (2004) Whither bioethics? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 10 (1), 7173. 4. Loughlin, M. (2004) Camouage is still no defence another plea for a straight answer to the question what is bioethics? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 10 (1), 7583. 5. Dans, A., Dans, L. & Silverstre, M. (2008) Painless Evidence-Based Medicine. Chichester: Wiley. 6. Loughlin, M. (2009) The basis of medical knowledge: judgement, objectivity and the history of ideas. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 15 (6), 935940. 7. Al-Al-Assaf, A. F. & Schmele, J. A. (eds) (1993) The Textbook of Total Quality in Healthcare. Delray Beach, FL: St Lucie Press. 8. Loughlin, M. (2002) Ethics, Management and Mythology. Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press. 9. Seedhouse, D. F. (1999) Camouage is no defence a response to Kottow. Journal of Medical Ethics, 25, 4448. 10. Loughlin, M. (2002) Arguments at cross-purposes: moral epistemology and medical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 28, 2832.

11. Loughlin, M., Upshur, R., Goldenberg, M., Bluhm, R. & Borgerson, K. (2010) Philosophy, ethics, medicine and health care: the urgent need for critical practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 249259. 12. Wall, A. (1994) Riposte: behind the wallpaper: a rejoinder. Health Care Analysis, 2 (4), 317318. 13. Bartlett, A. & Preston, D. S. (2003) Not nice, not in control. Philosophy of Management, 3 (1), 3746. 14. Loughlin, M. (2002) On the buzzword approach to policy formation. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 8 (2), 229242. 15. Loughlin, M. (2004) Orwellian quality the bosses revolution. Chapter 2. In Unmasking Health Management A Critical Text (eds M. Learmonth & N. Harding), pp. 2539. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science. 16. Mittra, I. (2009) Why is modern medicine stuck in a rut? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 52 (4), 500517. 17. Loughlin, M. (2007) Thinking: where to start. Chapter 9. In Prioritising Child Health: Principles and Practice (ed. S. Roulston), pp. 5162. London: Routledge. 18. Miles, A., Bentley, P., Polychronis, A., Grey, J. E. & Price, N. (1998) Recent progress in health services research: on the need for evidencebased debate. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 4, 257265. 19. Miles, A., Bentley, P., Polychronis, A., Grey, J. E. & Price, N. (1999) Advancing the evidence-based healthcare debate. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 5, 97101. 20. Miles, A., Charlton, B. G., Bentley, P., Polychronis, A., Grey, J. E. & Price, N. (2000) New perspectives in the evidence-based healthcare debate. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 6, 7784. 21. Miles, A., Grey, J. E., Polychronis, A., Price, N. & Melchiorri, C. (2003) Current thinking in the evidence-based healthcare debate. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 9, 95109. 22. Miles, A. & Loughlin, M. (2006) Continuing the evidence-based health care debate: the progress and the price of EBM. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 12 (4), 385398. 23. Miles, A., Loughlin, M. & Polychronis, A. (2007) Medicine and evidence: knowledge and action in clinical practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13 (4), 481503. 24. Miles, A., Loughlin, M. & Polychronis, A. (2008) Evidence-based health care, clinical knowledge and the rise of personalised medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14 (5), 621649. 25. Simon, J. (2011) Progress in medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , (in this edition: ditto for all references up to 60). 26. De Vreese, L. (2011) Evidence-based medicine and progress in the medical sciences. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 27. Devisch, I. (2011) Progress in medicine: autonomy, oughtonomy & nudging. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 28. Penston, J. (2011) Statistics-based research: a pig in a poke. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 29. Crowther, H., Lipworth, W. & Kerridge, I. (2011) EBM and epistemological imperialism. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 30. Buetow, S. (2011) The virtue of uncertainty in health care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 31. Marcum, J. (2011) The role of prudent love in the practice of clinical medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 32. Gelhaus, P. (2011) Robot Decisions: the importance of virtuous judgement in clinical decision-making. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 33. Meagher, K. (2011) Considering virtue: public health and clinical ethics. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 34. Buetow, S. & Entwistle, V. (2011) Pay-for-virtue: an option to improve pay-for-performance. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 35. Mitchell, D. (2011) Four alternatives to a reductive view of knowledge. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , .

3 3

60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

jep_1748

Editorial

M. Loughlin et al.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

36. Upshur, R. (2011) Commentary on Mitchell. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 37. Donetto, S. & Cribb, A. (2011) Researching involvement in health care practices. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 38. McClimans, L., Dunn, M. & Slowther, A.-M. (2011) Health policy, patient-centered care and clinical ethics. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 39. Nunn, R. (2011) Mere anecdote: evidence and stories in medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 40. Macnaughton, J. (2011) Medical humanities challenge to medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 41. Henry, S., Forman, J. & Fetters, M. (2011) Tacit clues in doctor-patient interaction. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 42. Braude, H. (2011) Tacit clues and the science of clinical judgement. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 43. Hutchinson, P. & Read, R. (2011) Commentary on Henry et al. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 44. Little, M., Gordon, J., Markham, P., Rychetnik, L. & Kerridge, I. (2011) Virtuous acts as practical medical ethics: an empirical study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 45. Calder, G. (2011) Commentary on Little et al. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 46. Gupta, M. (2011) Improved health or improved decision-making: ethical goals of EBM. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 47. Duncan, P. & Stephenson, A. (2011) Systems, contexts and the good health care practitioner. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 48. Loughlin, M. (2011) Criticising the data: some concerns with empirical approaches to ethics. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 49. Fulford, B. (2011) The value of evidence and evidence of values. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 50. Thornton, T. (2011) Radical, liberal values-based practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 51. Gupta, M. (2011) Values-based practice and bioethics. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 52. Brecher, B. (2011) Which values? And whose? A reply to Fulford. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 53. Hutchinson, P. (2011) The philosophers task: VBP and bringing to consciousness. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 54. Sestini, P. (2011) Epistemology and ethics of EBM: a response to comments. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 55. Goldenberg, M. (2011) A response to Sestinis response. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 56. Whiting, D. (2011) Abortion and referrals for abortion. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 57. Sehon, S. & Stanley, D. (2011) Taking Procrustes Axe to Professor Fishers response. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 58. Howick, J. (2011) Stats.Con by James Penston. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 59. Tonelli, M. (2011) The philosophy of evidence-based medicine by Jeremy Howick. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . 60. Kingma, E., Chisnall, B. & McCabe, M. M. (2011) Report on workshops in the philosophy of medicine & health care at KCL, Centre for

61.

62.

63.

64.

65. 66.

67.

68. 69.

70. 71. 72.

73.

74.

75.

76. 77.

78.

79.

Health Humanities. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, , . Cartwright, N. & Munro, E. (2010) The limitations of RCTs in predicting effectiveness. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 260266. Thompson, R. P. (2010) Causality, mathematical models and statistical association: dismantling evidence-based medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 267275. Sehon, S. & Stanley, D. (2010) Evidence and simplicity: why we should reject homeopathy. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 276281. Fisher, P. (2010) Ockhams Razor or Procrustes Axe? Why we should reject philosophical speculation that ignores fact. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 282283. Worrall, J. (2010) Evidence: philosophy of science meets medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 356362. Bluhm, R. (2010) Evidence-based medicine and philosophy of science. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 363 364. Hamilton, R. (2010) The concept of health: beyond normativism and naturalism. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 323 329. Tonelli, M. R. (2010) The challenge of evidence in clinical medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 384389. Goodman, K. (2010) Comment on Tonelli, The challenge of evidence in clinical medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 390391. Penston, J. (2011) Stats.Con. London: The London Press. Howick, J. (2011) The Philosophy of Evidence-Based Medicine. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. Loughlin, M. (2010) Epistemology, biology and mysticism: comments on Polanyis tacit knowledge and the relevance of epistemology to clinical medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 298300. Henry, S. (2010) Polanyis tacit knowing and the relevance of epistemology to clinical medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 292297. Loughlin, M. (2008) Reason, reality and objectivity: shared dogmas in the way both scientistic and postmodern commentators frame the EBM debate. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14 (5), 665 671. Popper, K. (1961) Facts, standards, and truth: a further criticism of relativism (Addenda). In The Open Society and Its Enemies, edn (ed. ), pp. 369396. London: Routledge. 1977. Hume, D. (1989) A Treatise of Human Nature. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Sestini, P. (2010) Epistemology and ethics of evidence-based medicine: putting goal-setting in the right place. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 301305. Goldenberg, M. (2010) From Popperian science to normal science. Commentary on Sestini. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 306309. Hill, D. (2010) Abortion and conscientious objection. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16 (2), 344350.

6 6

56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109

2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Journal Code: JEP Article No: 1748 Page Extent: 8

Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited Proofreader: Jason Delivery date: 29 July 2011 Copyeditor: Elaine

AUTHOR QUERY FORM

Dear Author, During the preparation of your manuscript for publication, the questions listed below have arisen. Please attend to these matters and return this form with your proof. Many thanks for your assistance.

Query References q1 q2

Query AUTHOR: revealed in this sentence has been changed to revealing. Is this revision correct to make clear the sense of the sentence? AUTHOR: The original reference citations were cited out of order and have been renumbered from Reference 2 (originally Reference 3) onward, and the reference list has been renumbered accordingly. Please conrm that it is OK. WILEY-BLACKWELL: Please supply the volume numbers and page ranges for References 2560 after pagination. Please also conrm it is correct to add 2011 as the year of publication for all these references. AUTHOR: Please conrm the author names added for Reference 44 are correct. AUTHOR: Chisnall, B. & McCabe, M. M. have been added as the co-authors for Reference 60 according to relevant citation of these authors mentioned in the text. Please conrm this is correct. AUTHOR: Please provide the edition number and editors name (if applicable) for Reference 75. Please also be noted that there are two years (1961 and 1977) in this reference; please conrm which one is the correct year of publication.

Remark

q3

q4 q5

q6

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- AIRs-LM - MATH 10 Quarter 4-Week 4-To-5 - Module-4Document20 pagesAIRs-LM - MATH 10 Quarter 4-Week 4-To-5 - Module-4joe mark d. manalang88% (8)

- Kit-Wing Yu - A Complete Solution Guide To Real and Complex Analysis II-978-988-74156-5-7 (2021)Document290 pagesKit-Wing Yu - A Complete Solution Guide To Real and Complex Analysis II-978-988-74156-5-7 (2021)HONGBO WANGNo ratings yet

- Carol Dweck Revisits The 'Growth Mindset'Document4 pagesCarol Dweck Revisits The 'Growth Mindset'magdalenaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 (p1) - The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumDocument58 pagesModule 2 (p1) - The Teacher As A Knower of CurriculumTRISHA MAY LIBARDOSNo ratings yet

- Hot Spot 3 SBDocument114 pagesHot Spot 3 SBAnalía Villagra89% (19)

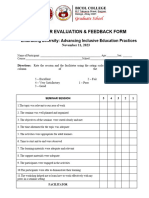

- Seminar Evaluation and Feedback FormDocument2 pagesSeminar Evaluation and Feedback FormMa. Venus A. Carillo100% (2)

- Activity Proposal For EnrichmentDocument3 pagesActivity Proposal For EnrichmentJayson100% (4)

- Quine - The Ways of ParadoxDocument11 pagesQuine - The Ways of ParadoxweltbecherNo ratings yet

- HCTN 24Document17 pagesHCTN 24Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Global Climatic Impacts of A CollapseDocument20 pagesGlobal Climatic Impacts of A CollapsePier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Constructing a FAMOUS ocean model without flux adjustmentsDocument19 pagesConstructing a FAMOUS ocean model without flux adjustmentsPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Simulating The Last Glacial Maximum With The Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere General Circulation Model Hadcm3Document33 pagesSimulating The Last Glacial Maximum With The Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere General Circulation Model Hadcm3Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- HCTN 15Document16 pagesHCTN 15Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- HCTN 25Document34 pagesHCTN 25Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Predicted Changes in Methane Emissions From Wetland Using IMOGENDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Predicted Changes in Methane Emissions From Wetland Using IMOGENPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- HCTN 70Document17 pagesHCTN 70Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Design of Coupled Atmosphere/ Ocean Mixed-Layer Model Experi-Ments For Probabilistic PredictionDocument38 pagesDesign of Coupled Atmosphere/ Ocean Mixed-Layer Model Experi-Ments For Probabilistic PredictionPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Simulations of Present-Day and Future Climate over Southern AfricaDocument37 pagesSimulations of Present-Day and Future Climate over Southern AfricaPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Climate-Land Carbon Cycle Simulation of The 20Th Century: Assessment of Hadcm3Lc C4Mip Phase 1 ExperimentDocument27 pagesClimate-Land Carbon Cycle Simulation of The 20Th Century: Assessment of Hadcm3Lc C4Mip Phase 1 ExperimentPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Dynamical properties of TRIFFID dynamic vegetation modelDocument24 pagesDynamical properties of TRIFFID dynamic vegetation modelPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Handling Uncertainties in The UKCIP02 Scenarios of Climate ChangeDocument15 pagesHandling Uncertainties in The UKCIP02 Scenarios of Climate ChangePier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- HCTN 58Document16 pagesHCTN 58Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Assessing and Simulating The AlteredDocument21 pagesAssessing and Simulating The AlteredPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Climate-Land Carbon Cycle Simulation of The 20Th Century: Assessment of Hadcm3Lc C4Mip Phase 1 ExperimentDocument27 pagesClimate-Land Carbon Cycle Simulation of The 20Th Century: Assessment of Hadcm3Lc C4Mip Phase 1 ExperimentPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- HCTN 70Document17 pagesHCTN 70Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- HTTP Download - Southwestrda.org - Uk File - Asp File Events General PorrittDocument3 pagesHTTP Download - Southwestrda.org - Uk File - Asp File Events General PorrittPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Global andDocument18 pagesThe Relationship Between Global andPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- COP9Document16 pagesCOP9Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Climate GreenhouseDocument71 pagesClimate GreenhousedaniralNo ratings yet

- An Investigation Into The Mechanisms ofDocument34 pagesAn Investigation Into The Mechanisms ofPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Journal 150Document19 pagesClimate Change Journal 150Pier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Anthropogenic Climate Change ForDocument61 pagesAnthropogenic Climate Change ForPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Anthropogenic Climate Change ForDocument61 pagesAnthropogenic Climate Change ForPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Amazon Dieback Under Climate-CarbonDocument29 pagesAmazon Dieback Under Climate-CarbonPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Economic Costs of Stabilizing ClimateDocument8 pagesEconomic Costs of Stabilizing ClimatePier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Global WarmingDocument20 pagesGlobal WarmingPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Ams DeclarationDocument2 pagesAms DeclarationPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- Grammar in Use Unit 22Document3 pagesGrammar in Use Unit 22Morteza BarzegarzadeganNo ratings yet

- Simon Abbott - Electrical/Mechanical: Curriculum VitaeDocument3 pagesSimon Abbott - Electrical/Mechanical: Curriculum Vitaesimon abbottNo ratings yet

- English Skills (3850) HandbookDocument75 pagesEnglish Skills (3850) HandbookEddieNo ratings yet

- Why Neoliberal Institutionalism Will Prevail: An Critical Analysis On Why Neoliberalism Goes Beyond NeorealismDocument9 pagesWhy Neoliberal Institutionalism Will Prevail: An Critical Analysis On Why Neoliberalism Goes Beyond NeorealismEmma ChenNo ratings yet

- 8MA0 21 MSC 20201217Document8 pages8MA0 21 MSC 20201217xiaoxiao tangNo ratings yet

- Cot Past PresentationsDocument8 pagesCot Past Presentationsapi-310062071No ratings yet

- Administrative and Supervisory Structure in Pakistan: Unit 8Document27 pagesAdministrative and Supervisory Structure in Pakistan: Unit 8Ilyas Orakzai100% (2)

- State Common Entrance Test Cell, Maharashtra State, MumbaiDocument2 pagesState Common Entrance Test Cell, Maharashtra State, MumbaiRitesh patilNo ratings yet

- Mules School PLC ProfileDocument2 pagesMules School PLC Profileapi-288801653No ratings yet

- Annex-C-Checklist-of-Requirements SampleDocument2 pagesAnnex-C-Checklist-of-Requirements SampleKassandra CruzNo ratings yet

- Appleget Tracy Educ 240 Kinder-Polka Lesson PlanDocument16 pagesAppleget Tracy Educ 240 Kinder-Polka Lesson Planapi-253429069No ratings yet

- Learning To Unlearn Faulty Beliefs and PDocument12 pagesLearning To Unlearn Faulty Beliefs and PARFA MUNAWELLANo ratings yet

- Law of Contract - IIDocument5 pagesLaw of Contract - IIjayanth prasad0% (1)

- Lesson Plan 7Document3 pagesLesson Plan 7Mirela AnghelinaNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 Science Focus and EpicenterDocument2 pagesGrade 8 Science Focus and EpicenterRe BornNo ratings yet

- 2013-S2 CVEN9822x2474Document5 pages2013-S2 CVEN9822x2474April IngramNo ratings yet

- Intro to Environmental EngineeringDocument232 pagesIntro to Environmental EngineeringAnshul SoniNo ratings yet

- VTU scheme of teaching and examination for III semesterDocument114 pagesVTU scheme of teaching and examination for III semesterIshwar ChandraNo ratings yet

- King's English 2012Document3 pagesKing's English 2012cabuladzeNo ratings yet

- Amity Admission Pushp ViharDocument4 pagesAmity Admission Pushp Viharpraveen4_4No ratings yet

- Book ReviewDocument3 pagesBook ReviewKristine Mae Canda100% (1)

- Home 168 Manila OJT Partnership ProposalDocument18 pagesHome 168 Manila OJT Partnership Proposal168 HomeNo ratings yet

- Grocers, Goldsmiths, and Drapers in Shakespeare's TheaterDocument49 pagesGrocers, Goldsmiths, and Drapers in Shakespeare's Theaterbrm17721No ratings yet