Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10 1 1 100 9142

Uploaded by

talanchukOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10 1 1 100 9142

Uploaded by

talanchukCopyright:

Available Formats

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

Strategic Alignment Revisited: Connecting Organizational Architecture and IT Infrastructure

Chris Sauer and Leslie Willcocks Templeton College, University of Oxford, UK Warwick Business School Email chris.sauer@templeton.oxford.ac.uk; willcockslp@aol.com

Abstract

Companies often find the rigidity of information technology infrastructures a barrier to change. This is increasingly problematic as, faced with high competitive intensity and environmental turbulence, boards and executive teams seek to formulate and execute dynamic strategy. In the absence of a clearly defined, long-term strategic plan, the IT infrastructure platform needs to be designed and managed in concert with organisational design to achieve the degrees of flexibility the executive team most expects to need. The paper combines IT architecture with multivariate theories of organisational fit into an activity that creates a joint architecture of IT and organisation. The distinctive advantage of the approach is that the architecture is harmonised to the increasingly widespread desire to make strategy on the run. Based on a 98 organization study, we describe relevant concepts, roles and practice for achieving an Organisational Architecture.

1. Introduction

Organisation and flexibility constitute a combination that is almost universally desired but found in practice to be very much at odds. So while companies vaunt their flexibility, when put to the test their response is too often limited by inertia deriving, from among other sources, rigid information technology (IT) infrastructure. The contortions undergone by traditional PC manufacturers responding to Dell, booksellers to Amazon, and insurance companies to DirectLine underlines both the difficulty and the

competitive implications of not being responsive to unanticipated futures. Paradoxically, the current business climate is at the same time suited and unsuited to developing flexibility. On the one hand companies have the time to consolidate, put their house in order, and build for the future while on the other hand they are focused on cost saving and paring their operations and overheads to the minimum. Investment is limited. It is tempting therefore to cut back on developments for the future whether they be skills and capabilities or information technology (IT). Unfortunately, they are complementary both are required. From the early 1960s we have known that certain kinds of organisational design promote innovation and adaptiveness[1]. Only in the last decade have we learnt the extent to which IT can enable or constrain adaptive response [2]. Creating a flexible platform for uncertain futures requires investment in an architecture that will enable rapid deployment of new IT. Such a platform comprises not merely technical infrastructure but also technical specialists and suppliers and the organisation/s through which they function. Delivering a flexible platform is timeconsuming and difficult to achieve. Securing support for the requisite investment is challenging when many companies have reverted to viewing IT as a troublesome cost. This papers contribution is to show why investment is required in a new practical discipline we term Organisational Architecture, and to set out its building blocks in terms of concepts, roles and practice. We thus extend Enterprise Architecture and certain theories of organisational design termed organisational architecture by showing how to achieve a joint architecture of IT and

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

organisation harmonised to the increasingly widespread desire to make strategy on the run [3].

2. Research Base

The argument is based on prior research [4] and experience in combination with insights drawn from the various literatures addressing dynamic strategy, organisational design, and flexibility [5]. This research was initially motivated by a desire to understand how companies IT functions were coping with the challenge of being prepared for the kinds of unpredictable demands created by the dot.com boom. Research was carried out throughout 2000 and early 2001 into 97 corporations in USA, Europe and Australia. Over 140 executives were interviewed or surveyed. Questioning covered their e-business models and initiatives and how these related to building the requisite technology. Interviews typically lasted between 45 minutes and two hours. Companies were drawn from a wide range of sectors including technology suppliers, distributors, financial services firms including credit card, stock broking, insurance and banking businesses, information providers, pharmaceutical companies, utilities, and a range of retailers and service operations. One research outcome was published as a market intelligence report in 2001[6]. This process taught us two key lessons: (1) that the issue of being prepared for unpredictable futures was a continuing concern for organisations beyond the immediate turbulence of e-business; and (2) that our conceptualisations of the kind of platform firms required could not be exclusively technological but should also embrace organisational design. We therefore revisited our case studies and have continued to engage with executives through 2002/3 to further explore and develop our emerging conceptualisation of Organisational Architecture. In some cases this engagement has taken the form of taped and transcribed semi-structured interviews, and in others it has involved presentations and discussions with groups of managers including a number with responsibility for aspects of Organisational Architecture. We use examples drawn from our research throughout.

3. Evolution Of Architecture

Organisational

In our usage, Organisational Architecture is the practice of designing and managing the combined infrastructure of

organisational structure and IT that together support company strategy. It is relevant to all large companies but the need has become most apparent and pressing where strategy is dynamic whether by design or default. For this reason, our discussion focuses principally on the issue of achieving flexibility. There are three key ingredients implicit in our adoption of the term Organisational Architecture interaction between organisation and IT; multivariate fit; and the discipline of IT architecture. First, IT and organisation increasingly function in concert. For example, retail banks worldwide have for years striven to shift from productbased structures we can send you three account statements but not in the same envelope to focus on the customer. Their speed of change has been geological because of the inflexibility of the vast IT infrastructures they have laid down over so many years. Todays UK National Health Service confronts a similar issue. Radical reform of clinical and administrative practices to allow treatment of the patient as a single individual requires reorganisation but this can only be effected when a new infrastructure has been installed that will enable sharing of patient data across all NHS locations. Conversely, organisations find that in order to exploit the opportunities new IT can present, they need to re-organise. When IBM embarked on its turnaround strategy in the early 1990s, it recognised that it could reengineer general procurement and make savings through consolidated purchasing but to achieve this it needed a global procurement function in addition to the new technology. This reciprocal interaction between IT and organisation demands management through a unifying authority. The second ingredient is the core idea within studies of economics and organisation of multivariate fit. In organisation theory this theme has been developed over some 30 years [7]. Coming from a different tradition of organisational economics, Brickley, Smith and Zimmerman likewise adopt a multivariate theory of fit [8]. Different authors have emphasised different variables drawing from an extensive range including task, people, formal organisational arrangements (including unit groupings, structures, coordination and control systems, job design, work environment, HR systems, reward systems, and physical location) and informal organisation (including leadership, norms, values, intragroup relations, intergroup relations, informal working arrangements, communication and influence patterns, key roles, climate and power politics).

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

While these traditions do acknowledge the role of information and technology, neither addresses the role of information technology either as an enabler or a constraint. Specialists in technology studies have been more alert to technologys key role in organisations [9]. But even researchers in the management of Information Systems/Information Technology (IS/IT) who have taken a multivariate approach have typically thought in terms of a long-term strategic plan with the design of organisation and IT as occurring sequentially. They have not considered design for flexibility. The third ingredient is IT architecture which refers to the IT sub-discipline most associated with preparing for the future. IT architects determine which technologies (hardware, software, networks, protocols, and standards) are acceptable in an organisations IT infrastructure and define a blueprint for how they should be connected together. By doing so they aim to strike the right balance between having a limited set of compatible components which restricts what can be achieved for the business and a more varied but less compatible set of components that increases the possibilities. The art of IT architecture lies in trading off a range of parameters including time, cost, quality, security, risk, and resilience among others against the degree of technological and, by implication, organisational flexibility the architecture permits. Perhaps because of what Michael Earl has called the ambiguity of IT [10], both theorists and managers have preferred to see ITs role as a delivery technology that has often by chance influenced how the organisation functions rather than as a crucial contributor to flexible organisation. However, our studies and experience suggest that it is possible to map an evolutionary path in the management of IT towards increasing emphasis and focus on the relationship between IT and organisation with a view to achieving flexibility (see Figure 1). The most basic application of IT is Automation of existing business processes on a case-by-case basis within business functions[11]. If this has any organisational effects, they are likely to be accidental. The fundamental objective is to take labour out of the task. Alignment aims to ensure that the application of IT matches the strategic needs of the business[12]. The rationale is that if a companys structure derives from its determining how to execute its strategy, then if IT is designed to reflect this it will thereby

support strategy execution. This works to a degree for an established strategic plan and organisational structure. However, it is timeconsuming, risky and expensive to redesign and re-implement IT infrastructure which thereby serves as a brake on change. Alignment therefore reinforces the existing organisation. One particular form of alignment, the federal structure [13] has sought to alleviate this problem through IT architecture. One objective sometimes set for such an architecture is to anticipate and support future developments that may be demanded of the IT function. However, this objective can be and often is undermined by further objectives. For example, an IT architect may be asked to restrict the technologies that can be used in order to facilitate bulk purchasing of IT facilities or to reduce the range of technical skills required. The intensely technical and highly conceptual nature of the role means that although in principle IT architects are often charged with anticipating future business needs, in practice they are almost never privy to the top teams thinking about its future strategy, and are rarely strongly competitively or organisationally focused. Safeways experience with its ABC loyalty card and associated data mining illustrates the point. Anticipating the competitive needs of the business in the 1990s, Safeway built a sophisticated data warehousing and data mining infrastructure that permitted micromarketing. Organisationally, the business lacked the capabilities to execute micromarketing successfully on a sufficiently large scale to justify the continued IT investment. Despite their best endeavours, IT architects alone are rarely able to deliver a sufficiently flexible platform that meets the real needs of the business. Reverse alignment involves the adoption of enterprise systems (ERP) on the basis that they provide a common upgrade path because the supplier continually enhances the technology and a common platform that allows extensive interconnection across a large, complex organisation. Adopting companies have chosen to redesign their business around the IT systems. This approach has certainly supported the development of greater integration across organisational units within the existing structure. But, as one CIO put it to us, ERP is like pouring wet concrete all over your organisation because the organisational structure is a parameter in the implementation of the software. Changing the organisation means re-implementing the ERP system.

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

Over time, then, ITs role in businesses has evolved from being narrowly focused on business processes to having far greater influence on the way the structure operates as an organisation. As the sociologist, Bruno Latour, has put it, it is no longer clear if a computer system is a limited form [of] organization or if an organization is an expanded form of computer system[14].

4. The Next Step Real Options

In our studies of both established and start-up companies the most common form of preparation for the future proved not to be the creation of a universally flexible platform. Rather we saw companies taking a more concrete approach by exploring real options [15]. These are highly specific experiments designed in part as a hedge against future need. They combine anticipation of the future with creation of the future. They are a distinct strategy but also represent a component of the final stage of evolution to Organisational Architecture the development of flexible capabilities (see Figure 1 and below). In the 1990s, Safeway created a number of real options. It established a detailed data warehouse of customer information for micro-marketing. It established an Internet shopping facility, Collect-and-Go. And it pioneered customer scanning in-store (Shop-and-Go) to enable self-checkout (EasiPay) to abolish checkout queues. Each of these initiatives required significant IT investment but they varied as to the organisational change that accompanied them. Micro-marketing was not well supported organisationally and was not pursued. Shop-and-Go had an extended life with some 160 stores being reconfigured to support it. It lasted and evolved as a continuing experiment for several years. Collect-and-Go was more short-lived, most probably a victim of Safeways reversion to a high-low price strategy. Electrocomponents, the parent of global electrical and electronic component distributor, RS Components, started its journey into e-business by making an initial investment in a web-based catalogue. It established a separate e-business unit to develop this thereby keeping it isolated from business-as-usual so that it could be more easily managed as an innovation and with the potential that it could be closed down without impact on core business if it proved unsuccessful. In the event, it is today a successful sales channel. Having done enough to feel confidence that the first option was likely to be successfully adopted, Electrocomponents started to set up other

options such as offering its customers eprocurement support as well as engaging in consolidated procurement from its own suppliers. This latter option revealed the need for both technology and organisation to be appropriate to the need. The initial option to establish a global procurement unit proved constrained by the lack of a shared IT infrastructure which made it prohibitive to monitor existing country-based procurement. Investigation indicated that a single shared ERP system was inappropriate to the very different levels of business conducted in different countries, so a regional ERP infrastructure was planned and the organisation adjusted to support consolidated procurement at the regional rather than the global level. A different distributor told us about its attempt to establish a direct to consumer business. The company failed to provide a distinct organisational location for the start-up so that it was pressed into a corner of a highly automated warehouse to whose facilities it was denied access. Unsurprisingly, the business was floundering and as a result, though established as an option, it failed to represent a real avenue for future growth and development. CitiPower, the Melbourne-based utility, hired its new CIO, Gill Lithgow specifically to create a platform for e-business. One of his early realisations was that the organisation was pursuing too many options for it to be able to advance the most promising ones. He therefore both set about limiting the investment in options and in establishing an organisational office and a process for monitoring those options it decided to continue. In summary, we saw a number of companies seeking to achieve a degree of flexibility by taking out real options. Some were IT-led and some were business-led. All were a gamble with uncertain outcomes. In some cases, there was just IT investment initially and in some there was organisational adjustment to complement the technology innovation. Where options were unsuccessful, some were unsuccessful as options and some were unsuccessful as business. Thus Safeways Shop-and-Go represented a very successful option that the company could have chosen to adopt but its micro-marketing option was less successful as an option because lacking organisational micro-marketing capability, it was never clear whether it had a future. Successes were less risky where complementary organisational change was viewed as integral to the option.

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

The further evolution of Organisational Architecture involves a shift from merely second-guessing or experimenting with future initiatives to institutionalising the dynamic capabilities that enable firms to flexibly explore, create and respond to new futures. A more sophisticated approach is called for.

5. The Broader Framework of Organisational Architecture

Many companies want a greater degree of freedom than is allowed by investment in specific real options. Organisational Architecture to support dynamic capabilities requires three principal elements: Design concepts terms for describing dynamic capabilities Architectural process ways of designing and implementing the Architecture Aftercare the continuing process of maintaining the Architecture

5.1. Architectural Design

Our starting point is to ask what characteristics do you want your organisation to have? It is a question that should be asked whenever strategy is reviewed and before an organisation settles on a desired structure. We draw upon several sources to define common architectural design requirements for different forms of flexibility and to show how their achievement requires designed interaction between information technology and organisation (see Table 1). These include earlier work as well as modern usage in journalism and everyday management discourse[16]. As we noted earlier, what makes Organisational Architecture so challenging is not merely that organisation and technology need to be knowledgeably combined (and traded-off) but also that the variables themselves have characteristics on multiple dimensions including cost, quality, accuracy/risk, efficiency/productivity, and speed. Thus, a company may seek to be efficient of process, rapidly and cheaply scalable, with a low risk infrastructure, but innovative only at higher cost and with no aspirations to increased reach. Achieving knowledgeable agreement at the top level to such a balance and overseeing delivery is the Organisational Architects task.

For design communication processes to function well there has to be some shared language. We believe that a basis exists in two complementary respects: common conceptual underpinnings, and emerging new organisational concepts that are deeply embedded in IT-based thinking. First, there is a common conceptual underpinning to the languages of organisation design and IT architecture. Both operate with the concepts of differentiation and integration, communication and control, standardisation and routinisation although the IT community cloaks them in its own jargon. Enterprise application integration (EAI) may sound intimidating to a business strategist, but it is merely the technologists seeking to achieve process integration. Where information technologists talk of best-of-breed systems, traditional organisational designers speak of functional differentiation in both cases their interest lies in achieving the advantages of specialisation. IT architects talk at length about standards and understand the tensions between autonomy and control as well as any organisational design consultant. However, while there are shared concepts, both the language of organisational design and that of IT architecture have limited purchase upon organisational adaptiveness and change. A further set of concepts is therefore required and these derive from recent attempts to provide some conceptual structure to dynamic strategy [17]. Table 2 summarises Brown and Eisenhardts core concepts, their contribution to achieving dynamic strategy, and their architectural character.

5.2. Architectural Process

We do not suggest that there is an established set of processes for successfully achieving and maintaining an appropriate architecture - experience is limited. However, we can infer certain elements of process from general design principles and from IT architecture in particular. As is the nature of design, there are no simple algorithms for balancing an organisations requirements and the design decisions that realise them. But two-way communication processes are essential. At the heart of this communication is the goal of creating a platform of organisational capability that permits certain degrees of flexibility against certain constraints such as cost, risk and resilience. This involves moderating unrealistic ambitions on the part of executive teams through understanding of the enabling and constraining characteristics of possible IT architectures, while at the same time informing

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

IT architects of the business needs that drive the demand for essential degrees of flexibility [18]. In summary, they involve asking the following questions of both the CEOs inner circle and the IT specialists and brokering their differing answers: What does the future look like? What aspects of the business and its technology will be core to that future? What does it mean for this company to be dynamic and flexible outside that core? What level of flexibility is achievable given that there will be some hard-toremove constraints? How can the company match its ambition and capability? The desired outcome is a jointly accepted position on the degree of flexibility required and its implications in terms of organisation and IT. The other principal element of process is implementation of organisational and IT change to establish the architecture. Because the architecture defines the organisation in terms of its future capabilities, this can be a significant transformation requiring leadership from the top. Oracle Corporations e-business initiative exemplifies this well. In the late 1990s Oracle wanted to create a platform for itself to exploit a range of possible opportunities. CEO Larry Ellison saw the potential for cost savings, customer service improvements, a shift to global account management, and more central oversight of country business activities. He recognised that a sufficiently flexible platform required a more centralised organisational structure supported by a common IT infrastructure. He also realised that he could only achieve this by securing country buy-in to greater centralisation. He thus set about changing country Managing Directors remuneration targets from being based on revenue to profit, at the same time as centralising IT and Marketing and offering the MDs these services for free. They were at liberty to retain their local IT and Marketing functions but they would have to believe that these added more to their profitability than they cost. The country MDs willingly accepted centralisation, thereby enabling a common IT platform to be established and common marketing strategies to be executed. Plainly Ellison wanted his own company to be a reference site (role model) for its own products and therefore was highly motivated to achieve his objectives, and this might have sharpened his awareness of what needed to be done. Whether or not his implicit understanding of the co-dependence of IT and

organisation and his adept change management were the result of his having special knowledge inaccessible to other companies, the importance of this example is its demonstration of the necessity of skilled change management in delivering a new Organisational Architecture. Others take a different approach. One manager who fulfils many aspects of the Organisational Architect role in a global consumer goods company takes a more bottom-up, incremental approach. He seeks out areas of the business where by applying architectural practice he can achieve a win that demonstrates to senior executives the value of Organisational Architecture so that they will subsequently seek him out to help them apply architectural practice more widely within their spheres of authority.

5.3. Architectural Aftercare

The experience of IT architecture also vividly demonstrates the need for aftercare. An architecture cannot and does not contain its own guarantee of longevity. As a compromise among competing demands it is immediately subject to the pressure for exceptions. Without a guardian, entropy results in complexity and disorder. Whatever value the architecture promoted dissipates. Architects and committees are called upon to police compliance[19]. The other aftercare issue is evolution of the architecture. Business change and technology advance both change the equation on which the architecture was initially predicated. A strategy of demerger and focus such as that pursued in recent years by the Kingfisher and P&O groups may promote the importance of experimentation over crossbusiness integration leading to legitimate architectural change. However, we have seen too little adoption and adaptation of flexible capabilities thus far to do more than draw attention to the need for continued review and supervision of the Organisational Architecture.

6. Conclusion

ITs increasing pervasiveness in businesses means that their IT infrastructure more and more defines their organisational characteristics. IT choices are thereby organisational choices. At a time when strategy is becoming less explicit and more dynamic, flexible execution depends heavily on having the right organisational capabilities. But, because IT constrains some organisational choices at the same time as enabling others, it

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

is inappropriate to ask information technology architects to design a flexible platform without giving them careful guidance as to the types/degrees of flexibility required. Because this guidance involves important trade-offs, it must be given by senior executives in the full knowledge of its potential future implications. Thus a bi-partite architectural activity is required in which organisation and IT infrastructure design are informed by deep knowledge of business vision and ambition, while at the same time that vision and ambition is matched and modified in the light of the limits imposed by the organisational and infrastructural design. Our approach assumes that long-term strategy is more about developing capabilities than achieving an advantageous and sustainable competitive position. So although the term Organisational Architecture sounds like a one-off project such as the design of a building, in fact it is more a continuing process to adjust and develop a platform that will give rise to and enhance capabilities. Thus we have used logical argument to establish the need for Organisational Architecture. We have used observation from the field and discussion with relevant executives to suggest that this is not merely a theoretical possibility but that companies are moving in the direction we indicate. Our observations have also helped us to give shape to our ideas which has ensured both that they have appeal to executives and that they are practically realistic. One aspect of which we have said little is who is to play the role of Organisational Architect. We contend that it must be a senior executive, possibly themself a member of the top executive team, but certainly with the trust of that team. It is essential to achieving a realistic compromise between costs and degrees of freedom that the Architecture is informed by the most realistic assessment of possible futures unmediated by layers of hierarchy. At the same time, this function must be IT-knowledgeable so as to understand the trade-offs implicit in any IT architecture. In our experience a few CEOs such as Larry Ellison of Oracle combine the relevant understanding, but most lack the technology background. Likewise not all CIOs have the relevant depth of understanding of the strategy and organisational design. Hence somebody such as a strategy director supported by a multi-functional team will in most cases be appropriate. Much as the Chief Information Officer role when first adopted was not a well established role but one into which individuals

were required to grow, so too we believe it is the case with the Organisational Architect. Those who currently fulfil some part of the role as we conceive it are pioneers necessarily feeling their way and experimenting. Our contribution is to offer some structure and coherence to what we see happening, but to the extent that not all of our suggestions are well tested, we must expect new, different and better ideas to emerge. For example, our application of Brown and Eisenhardts dynamic capabilities is indicative and may well be superseded as practice develops. Is an Organisational Architect required in every business? Our research does not as yet tell us because we started with a focus on organisational flexibility. The more a company required flexibility and the more pervasive IT was within it, the more it seemed that Organisational Architecture was required. Equally, as the research has developed, it has become apparent that the fundamental idea of creating a joint organisational design and IT architecture is as relevant to a commodity business seeking to become super-efficient or a professional services firm seeking to exploit its dispersed professional knowledge as it is to a high-tech company operating flexibly in dynamic markets. The organisational capabilities the Architect seeks to realise will vary but the principle remains intact. Similarly, while large, decentralised organisations are architecturally challenging because of their centrifugal tendencies, the basic issue of IT acting as an enabler and constraint also applies to smaller more centralised firms. Organisational Architecture may be easier to achieve but is nonetheless needed. This wider applicability of the concept reinforces the importance of Organisational Architecture at board level. But the issue of boardroom buy-in highlights a challenge if Organisational Architecture is for the long-term, will it justify the effort and investment in a time frame that will reward the board and senior executives for their foresight? In due course, we might expect that not only will the real options companies take out be factored into their share price but so too will the Organisational Architecture on the basis of what futures it enables. In the meantime, a more practical response will be to find principles of Organisational Architecture that can be applied and take effect in a shorter time frame. In summary, another way of putting what we are saying is dont delegate the provision of flexibility to the IT function and dont treat the creation of a flexible IT platform as somehow separable from your

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

organisation design. Instead, invest in Organisational Architecture and in doing so recognise that you are investing not in a product but a programme of reforming the way you make strategy, structure your organisation and plan your IT.

6. References

[1]. T. Burns and G.M. Stalker, Management of Innovation, Tavistock Publications, London (1961). [2.] M. Hammer and J. Champy, Reengineering the Corporation: a Manifesto for Business Revolution, HarperCollins, New York, (1993). [3]. M.A. Cusumano and C.C. Markides, Strategic Thinking for the Next Economy, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco (2001). [4] C. Sauer and L. Willcocks, Building the EBusiness Infrastructure: Management Strategies for Corporate Transformation, Business Intelligence, Wimbledon (2001). [5]. E.g. S.L Brown & K.M. Eisenhardt, Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Mass., (1998), R.T. Pascale, M. Milleman and L. Gioja, Surfing the Edge of Chaos: The Laws of Nature and the New Laws of Chaos, Crown Publications (2000). [6]. C.Sauer & L. Willcocks, Building the EBusiness Infrastructure: Management Strategies for Corporate Transformation, Business Intelligence, Wimbledon, 2001. [7]. Leavitt, H.J. Applied organizational change in industry: structural, technological and humanistic approaches, in J.G. March (ed.), Handbook of Organizations, Rand McNally, Chicago (1965); R.E. Miles and C.C. Snow, Fit, failure and the hall of fame, California Management Review, 26, 3, Spring, 10-28, (1984); R.E. Miles and C.C. Snow, Fit, Failure and the Hall of Fame: How Companies Succeed or Fail, Free Press, New York (1994); D. Miller, Configurations revisited, Strategic Management Journal, 17, 505-512 (1996); D.A. Nadler and M.L. Tushman, Competing By Design: The Power of Organizational Architecture, Oxford University Press, New York (1997). [8]. J.A. Brickley, C.W. Smith and J.L. Zimmerman, Teaching the economics of organization, Financial Practice and Education, 9, 2, 120124 (1999). [9]. K.B. Clark, What strategy can do for technology, Harvard Business Review, 67, 6, 94-98 (1989); A.M. Kantrow, The strategy-technology

connection, Harvard Business Review, 58, 4, 6-21 (1980). [10]. M.J. Earl, Private meeting of French Thornton Partnership Change Leadership Network, London, 26 February 2003. [11]. S.Zuboff In the Age of the Smart Machine: the Future of Work and Power, Basic Books, New York, (1988). [12]. J.C. Henderson and N. Venkatraman, Strategic alignment: a model for organizational transformation through information technology, in T. Kochan & M. Useem (eds),Transforming Organizations, Oxford University Press, New York (1992). [13]. R.W. Zmud, A.C. Boynton and G.C. Jacobs The information economy: A new perspective for effective information systems management, Data Base, Fall, 17-23, (1986). [14]. B. Latour, Social theory and the study of computerized work sites, in W.J. Orlikowski, G. Walsham, M.R. Jones and J.I. DeGross (eds.), Information Technology and Changes in Organizational Work, Chapman and Hall, London, 295-306 (1996). [15]. The options approach is also advocated in J. Ross, C. Beath, V. Sambamurthy and M. Jepson, Strategic levers to enable e-business transformations, CISR Working Paper No 310, MIT, Boston, Mass. (2000) where it is proposed as one of four IT infrastructure strategies. [16]. C. Sauer, Managing the Infrastructure Challenge, in L. Willcocks, C. Sauer & Associates, Moving to E-Business: The Ultimate Practical Guide, Random House, London, 2000; C.Sauer & L. Willcocks, Building the E-Business Infrastructure: Management Strategies for Corporate Transformation, Business Intelligence, Wimbledon, 2001. [17]. S.L Brown and K.M. Eisenhardt, Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Mass. (1998); K.M. Eisenhardt and S. Brown, Patching: Restitching Business Portfolios in Dynamic Markets, Harvard Business Review, 72-82, May-June (1999); K.M. Eisenhardt and D. Sull, Strategy as Simple Rules, Harvard Business Review, 106-116, Jan (2001). [18]. C. Sauer and L.P. Willcocks, The Evolution of the Organizational Architect, Sloan Management Review, 43, 3, 41-49, Spring (2002). [19]. C.U. Ciborra and Associates, From Control to Drift: The Dynamics of Corporate Information Infrastructures, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2000).

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

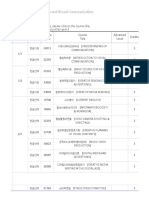

Design Requirements

Flexible process

Table 1: Design Requirements For Flexibility Description Interaction of IT and Organisation

Involves continual adaptation of business process logic and assembly/disassembly of process elements. Ability to obtain increased value from assets integral to the business including databases, knowledge bases, algorithms, and business processes. The underlying capital (buildings, inventory, relationships etc), HR and IT investment that permits the business to function. Ability to think differently and creatively, and to bring new ideas into use. Ability to withstand turbulence and shock. Increasingly pre-packaged IT software defines (best practice) process structure and organisation. Process logic change requires organisational change. Today, increasingly about exploiting different forms of intellectual property embedded, or part-embedded in IT. Only exploitable if organisational incentives are in place and silo ownership barriers removed. IT can substitute for other forms of infrastructure but only if the organisation is redesigned, eg an estore substitutes for a branch network so long as the back office/logistics is redesigned. Product and process design innovation are highly dependent on IT, but inappropriate structures and immature capabilities block translation of ideas into use. Managing shocks requires organisational choices about loose/tight coupling and provision of slack resources within business processes and IT to absorb and mitigate the impact of shock. Product and process knowledge is increasingly concentrated in few individuals and embedded in IT. Diffused knowledge necessary to support growth and avoid losses during retrenchment. Business unit structure needs to be balanced against increased industry/market specialisation of packaged software. Orchestration of the supply chain to permit entry into new territories requires a combination of organisational and IT decisions. Organisational processes needed to motivate learning. Management consultancies knowledge bases only started to work once they solved the problem of sharing expertise. Data warehouses and knowledge banks are easily created but require structures, roles and skills to interpret their contents and act effectively. Requires information resources (email, collaboration technologies etc). Critical balance lies between structuring (through systems) and enabling (through resources).

Asset exploitation

Flexible infrastructure

Innovation

Resilience

Scale

Ability to scale up or down as required.

Scope

Ability to vary products and markets as required. Ability to vary geographical scope.

Reach

Learning

Ability to capture knowledge from innovation and execution.

Responsiveness

Ability to respond to contextual turbulence economic, competitive, political, regulatory, environmental, social, technological.

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004

Realm of Organisational Architecture

Organisational complexion of IT Automation Alignment Reverse Alignment Real Options Flexible Capabilities

Organisational effects by accident

Reinforces established organisational structure and processes

Fits organisation to chosen information technology

Ability to turn on IT options must be matched by organisational options

Convergence of IT and organisational capabilities

Figure 1: The Evolution Of Organisational Architecture

Table 2: Architectural Concepts for Realising Flexible Capabilities Concept Description Contribution to Architectural Character Dynamic Strategy

Simple Rules high level heuristics that have wide applicability Co-adaptation a blend of business independence with adaptive inter-business collaboration Enable improvisation. Guide rapid, autonomous but coherent, decision-making Influences cost and speed in fast-moving markets. Emphasises adaptation in pursuit of domination in high potential markets Organisationally, decision-makers need to have autonomy and be freed from unnecessary constraints. Technologically, what is needed varies according to the content of the rule see example in text below. A key element is frequent joint focus across businesses on highly targeted areas of Group or Alliance opportunity and mutual advantage. Organisationally requires motivation and opportunity for interests to meet, be mixed, and resolved into action. Technologically requires superior data analysis to keep the focus in tune with the changing business. Organisationally, requires fast-moving people, processes and structures. Requires adaptable and responsive IT structure and specialists. The extensible IT platform they create needs to be shaped by understanding of the kinds of stimulation, eg acquisitions and de-mergers, product launches and exits, new forms of contract etc Modularity is usually based around core IT applications that fulfil common business functions. Modularity is achievable only if there are simple and constrained interconnections among modules. This requires collaborative design of both the technological interconnection strategy and the organisational interfaces. Organisationally, requires design that balances protection of ongoing business with promotion of experiments. Requires responsive technologists, and information technologies that can either be converted rapidly to industry-strength or detached and thrown away Organisationally requires staff selection and management processes attuned to the rhythm. Requires information technologists with developmental and operational processes aligned to the rhythm

Regeneration provocation of adaptive response through persistent stimulation to change

Evolves new and enhanced businesses and capabilities from established strengths. Avoids risk of stagnation.

Modularity having specialised organisational building blocks. Traditional differentiation with the addition of defined points of interconnection to enable plug and play Experimentation constant probing of the future through exploratory ventures

Permits focus on improvement. Provides speed of start-up/response if module can be acquired off the shelf. Increased ability to handle complexity, scale, expand and divest. Anticipates the future before it happens to you.

Time-pacing defining a rhythm of change that matches internal capabilities to the needs of the market

Institutionalises the right rate of change

0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE

10

You might also like

- Transdisciplinary Unified Theory: Ch. O. François GESI, Grupo de Estudio de Sistemas, Argentina KeywordsDocument8 pagesTransdisciplinary Unified Theory: Ch. O. François GESI, Grupo de Estudio de Sistemas, Argentina KeywordstalanchukNo ratings yet

- Organisational Structure and Elliot Jaques' Stratified Systems TheoryDocument135 pagesOrganisational Structure and Elliot Jaques' Stratified Systems Theorytalanchuk100% (1)

- Olena Bekh, James Dingley - Teach Yourself Ukrainian - 2003Document152 pagesOlena Bekh, James Dingley - Teach Yourself Ukrainian - 2003rginjc100% (4)

- The Foundations of The Scientific Study of Public Bureaucracy 0472113178-Ch1Document19 pagesThe Foundations of The Scientific Study of Public Bureaucracy 0472113178-Ch1Jon SearleNo ratings yet

- The Foundations of The Scientific Study of Public Bureaucracy 0472113178-Ch1Document19 pagesThe Foundations of The Scientific Study of Public Bureaucracy 0472113178-Ch1Jon SearleNo ratings yet

- Olena Bekh, James Dingley - Teach Yourself Ukrainian - 2003Document152 pagesOlena Bekh, James Dingley - Teach Yourself Ukrainian - 2003rginjc100% (4)

- Stafford Beer - The Brain of The FirmDocument60 pagesStafford Beer - The Brain of The FirmLaureano Gabriel Vaioli100% (2)

- Organizational ArchitectureDocument10 pagesOrganizational ArchitectureIskandar ZulkarnaenNo ratings yet

- Organizational ArchitectureDocument10 pagesOrganizational ArchitectureIskandar ZulkarnaenNo ratings yet

- Ackoff Misinformation SytemDocument11 pagesAckoff Misinformation SytemDianne BausaNo ratings yet

- A Systemic View of Transformational Leadership by Russell L. AckoffDocument15 pagesA Systemic View of Transformational Leadership by Russell L. AckofftalanchukNo ratings yet

- Organizational ArchitectureDocument10 pagesOrganizational ArchitectureIskandar ZulkarnaenNo ratings yet

- Autopoiesis and Cognition The Realization of The Living - Humberto Maturana and Francisco VarelaDocument86 pagesAutopoiesis and Cognition The Realization of The Living - Humberto Maturana and Francisco VarelaRodrigo Córdova ANo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- To Be Success Collage StudentDocument3 pagesTo Be Success Collage Studentdian luthfiyatiNo ratings yet

- Subject Guide: Northwestern UniversityDocument7 pagesSubject Guide: Northwestern UniversityZsazsaNo ratings yet

- ALCDocument25 pagesALCNoelson Randrianarivelo0% (1)

- Role of Media and Information in CommunicationDocument2 pagesRole of Media and Information in CommunicationRMG REPAIRNo ratings yet

- Tekhnologic - Learn. Try. ShareDocument10 pagesTekhnologic - Learn. Try. ShareABoseLopusoNo ratings yet

- Week 2Document4 pagesWeek 2John Denver De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Love Language TestDocument2 pagesLove Language Testrlolis407No ratings yet

- Fluid Identity Development TheoryDocument12 pagesFluid Identity Development Theoryapi-374823288No ratings yet

- Digital Citizenship BehavioursDocument15 pagesDigital Citizenship BehavioursAli Abdulhassan AbbasNo ratings yet

- 계명대학교bDocument5 pages계명대학교bExcel ArtNo ratings yet

- Mentoring and Evaluation FormDocument2 pagesMentoring and Evaluation FormGLAIZA MAE COGTAS100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Log in English 7: Republic of The Philippines Division of Mandaue CityDocument2 pagesDaily Lesson Log in English 7: Republic of The Philippines Division of Mandaue CityTeacher MaryNo ratings yet

- S3.5 India MR - Kumar PDFDocument27 pagesS3.5 India MR - Kumar PDFfaarehaNo ratings yet

- Gyan DarshanDocument5 pagesGyan DarshanRINU JAMESNo ratings yet

- Wireless Communication Systems Course OverviewDocument28 pagesWireless Communication Systems Course Overviewannapoorna c kNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Pupil Performance Using Fill-Me-Up StrategyDocument8 pagesAnalysis of Pupil Performance Using Fill-Me-Up Strategyvea verzonNo ratings yet

- Digital Marketing (DM) ChannelsDocument26 pagesDigital Marketing (DM) ChannelsMôhåmmëd Mėhdì ElámrįćhēNo ratings yet

- Netcom Module IVDocument53 pagesNetcom Module IVMC JERID C. BATUNGBAKALNo ratings yet

- Action Research in A.P.Document31 pagesAction Research in A.P.Ros A Linda100% (5)

- CRM ProjectDocument6 pagesCRM ProjectRama EbdahNo ratings yet

- Use of Local Culture in EFL ClassroomDocument20 pagesUse of Local Culture in EFL ClassroomFariha UNNo ratings yet

- AgendaSetting IntlEncyDocument21 pagesAgendaSetting IntlEncyMạnh ĐứcNo ratings yet

- Week29 - Unit 4 LunchtimeDocument5 pagesWeek29 - Unit 4 LunchtimeShantene NaiduNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Local SEODocument170 pagesA Guide To Local SEOMarko GrbicNo ratings yet

- Esl P2 MS 2021-2020Document22 pagesEsl P2 MS 2021-2020Mostafa HaithamNo ratings yet

- Political Activity and MemesDocument12 pagesPolitical Activity and MemesKim Bernardino100% (2)

- You Ve Got PwnedDocument80 pagesYou Ve Got PwnedaaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Orange and White Dotted High School ResumeDocument1 pageOrange and White Dotted High School Resumeapi-527477404No ratings yet

- Learn Content Writing in 12 WeeksDocument11 pagesLearn Content Writing in 12 WeeksK Kunal RajNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan Global InequalitiesDocument4 pagesUnit Plan Global Inequalitiesapi-506886722No ratings yet