Professional Documents

Culture Documents

UK

Uploaded by

Sanzida BegumOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

UK

Uploaded by

Sanzida BegumCopyright:

Available Formats

Banking regulation

One notable consequence of the recent global financial crisis is the recognition that existing regulation of financial institutions has failed. Self regulation via banking codes failed to prevent the 2008/09 banking crisis, as did national regulation. The growth in high risk trading of extremely complex financial products, including derivatives and options, and the increasing securitisation of assets, created what has widely been dubbed a shadow banking system, which increasingly operated outside of normal banking practices. Like all large businesses, banks are subject to regulation by the OFT and the Competition Commission. As early as 2001 the Competition Commission concluded that a number of the largest banks operated a complex monopoly in the supply of services to small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) which resulted in reduced competition to the detriment of the customers. For example, customers were reluctant to switch banks because they all offered very similar benefits. The tri-partite system Current banking regulation in the UK involves three organisations, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) the Bank of England and the Treasury. Until the banking crisis, UK banking regulation could be described as light-touch - in other words, regulators do not engage in aggressive regulation, preferring to intervene only when necessary, and only in limited ways. The main problem for the regulators was that the heavy-touch regulation might force global banks to seek out countries where regulations were less strict. In other words, they would move out of London, leading to huge job losses in the City. (Source: Reuters) The role of the FSA The main UK bank regulator is the Financial Services Authority (FSA). It has two main objectives:

To promote efficient and fair financial services To help consumers of financial services achieve a fair deal

To achieve this the FSA sets standards for the activities of banks and other financial businesses, and can take action to ensure these standards are met. Rules vs Principles Some critics of the US regulatory system maintain that it is too 'rule-based' and should move towards the European model of 'principle-based' regulation.

With rule-based regulation the regulators interpret the rules as laid down in law, and there is little room left for judgement or interpretation. Under a principles-based system the general principles are contained in legislation, and this gives regulators extra powers to to assess the behaviour of financial institutions. The Banking Act 2009 In order to protect depositors and to maintain financial stabilit, the Banking Act of 2009 gave the those organisations responsible for banking regulation the collective powers to deal with the crisis in the banking system. One of these powers is the ability to put a failing bank under temporary public ownership. The Turner Review In March 2009 Lord Turner, Chairman of the FSA, published the findings of his review into the banking crisis and recommended the following: More coordinated international banking regulation, especially the creation of a pan-European regulator 1. Banks to hold more assets 2. Regulation of liquidity 3. More information to be collected from those institutions that are part of the shadow banking system, like hedge funds. 4. More regulation of overseas banks by host countries - this recommendation is largely in response to the collapse of the Iceland banks, who were unregulated by the UK regulators, but UK citizens suffered large losses. 5. Control of bank employees remuneration 6. A review of bank's accounting practices

At last, sense seems to be entering the U.K. banking reform debate. I argued here two weeks ago that Project Merlin missed an important trick not addressing the U.K. mortgage famine, which is partly due to the chronic funding challenges faced by British banks. I also argued yesterday that the high cost and scarcity of U.K. bank lending was one of the biggest risks to the recovery and the reason why the Bank of England is right to be cautious about raising interest rates. So I view reports that George Osborne is considering ways to loosen the U.K.s tough liquidity rules as very positive news not just for bank investors but for anyone with a stake in the performance of the U.K. economy. If it is a sign the tide is finally turning on the fundamentalists at the Bank of England and Financial Services Authority who, egged on by the crude bank-bashing U.K. press, have had a free rein since the start of the financial crisis, then it cannot come soon enough.

The U.K. currently has some of the most draconian bank regulation in the world, its policymakers insisting on gold-plating international rules while arguing publicly for a break-up of the banks and a return to Victorian era capital ratios. The result has been to hobble an already fragile U.K. banking system just at the point it is most needed to finance a recovery. No one doubts that inadequate liquidity was one of the primary reasons for the banking crisis and that it was essential banks in future held more liquid assets. But the FSAs liquidity regime goes well beyond other countries. Barclays now has a total liquidity pool of 154 billion more than 10% of its balance sheet almost all of it tied up in zero-yielding cash and low-yielding government bonds. The cost of maintaining this liquidity pool was 900 million in 2010. Loosening the rules on what qualifies as liquid assets and reducing the liquidity buffer would free up funds for more profitable lending to the economy. Santander also this month cited the FSAs liquidity rules as a reason why it was cautious on its U.K. outlook this year. If the message is finally beginning to dawn on the Treasury that the BOE and FSA do not have a monopoly on wisdom and that the radical experiments being conducted on the U.K. banking sector, while fine in academic theory, are potentially ruinous in practice then this is an important moment in the crisis. It may mark the point at which the pendulum finally starts to swing back from the extreme banker-bashing that has characterized the U.K. debate for the last three years. That could have important implications for the outstanding Basel 3 negotiations and above all the context in which the Independent Banking Commission delivers its recommendations. If so, it could also mark the moment at which the huge regulatory discount hanging over the U.K. banking sector starts to lift.

You might also like

- Basics of Islamic InsuranceDocument11 pagesBasics of Islamic InsuranceSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Terms and Concepts For VivaDocument43 pagesTerms and Concepts For VivaSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Terry Towel IndustryDocument1 pageTerry Towel IndustrySanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Royal AholdDocument27 pagesRoyal AholdSanzida Begum100% (2)

- Multicollinearity, Heteroscedasticity and AutocorrelationDocument23 pagesMulticollinearity, Heteroscedasticity and AutocorrelationSanzida Begum100% (3)

- Internship Report2Document84 pagesInternship Report2Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument17 pagesTerm PaperSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Import, Export and RemittanceDocument29 pagesImport, Export and RemittanceSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Gold Bullion Standard: Sanzida Begum Id: 17-002Document6 pagesPresentation On Gold Bullion Standard: Sanzida Begum Id: 17-002Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Niversity OF Haka: Non Performing Loan: Causes and Consequences Course Name: Business Research MethodsDocument26 pagesNiversity OF Haka: Non Performing Loan: Causes and Consequences Course Name: Business Research MethodsSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Impact of Regional ConnectivityDocument7 pagesImpact of Regional ConnectivitySanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- HSBC Org1Document118 pagesHSBC Org1Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Training and Developing EmployeesDocument25 pagesTraining and Developing EmployeesSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- OpenningDocument7 pagesOpenningSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Non-Performing Loan: Causes & Consequences and Impact On Bank Profitability & Macroeconomic FactorsDocument2 pagesNon-Performing Loan: Causes & Consequences and Impact On Bank Profitability & Macroeconomic FactorsSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- City Bank participation in Bangladesh financial marketsDocument26 pagesCity Bank participation in Bangladesh financial marketsSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Blood Donar List PDFDocument5 pagesBlood Donar List PDFSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- History of DBBL and its CSR activitiesDocument13 pagesHistory of DBBL and its CSR activitiesSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Main BodyDocument25 pagesMain BodySanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Short NoteDocument6 pagesShort NoteSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- B 308Document27 pagesB 308Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Government Influence on Trade ControlsDocument18 pagesGovernment Influence on Trade ControlsSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- AlicoDocument7 pagesAlicoSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Short NoteDocument6 pagesShort NoteSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- B 308Document27 pagesB 308Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Bank Co. Act 2013Document6 pagesBank Co. Act 2013Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Bank Co. Act 2013Document6 pagesBank Co. Act 2013Sanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- Agriculture in BangladeshDocument5 pagesAgriculture in BangladeshSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- DefinationDocument8 pagesDefinationSanzida BegumNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

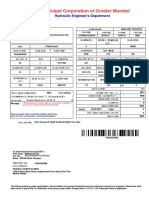

- Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai: Hydraulic Engineer's DepartmentDocument1 pageMunicipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai: Hydraulic Engineer's DepartmentFrancis AlbertNo ratings yet

- Cash Receivables Financial Reporting GuideDocument19 pagesCash Receivables Financial Reporting GuideMiguel Angelo JoseNo ratings yet

- TLA 2 - With AnswersDocument4 pagesTLA 2 - With AnswersMonique VillaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument489 pagesReportbad3106No ratings yet

- Managerial Accounting Vs Financial AccouDocument11 pagesManagerial Accounting Vs Financial AccouJermaine Joselle FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Smart Car Engine ShippingDocument3 pagesSmart Car Engine Shippingier362No ratings yet

- E-Commerce Mid Term Project PresentationDocument35 pagesE-Commerce Mid Term Project Presentationmyn11No ratings yet

- CH10 Sys N AppsDocument4 pagesCH10 Sys N AppsFrank Camizzi0% (1)

- RCBonly and The Insane Chain Gang LetterDocument17 pagesRCBonly and The Insane Chain Gang LetterMariyam Akmal0% (1)

- Final Supervision Checklist DocumentDocument5 pagesFinal Supervision Checklist Documentotis2ke9588100% (1)

- LOCATIONS VOCABULARY AND LISTENING PRACTICEDocument6 pagesLOCATIONS VOCABULARY AND LISTENING PRACTICEHan KimNo ratings yet

- Understanding HDFC Bank's Private Banking ServicesDocument18 pagesUnderstanding HDFC Bank's Private Banking Servicesritvik24No ratings yet

- Research Project Title: "AntiqueñoDocument3 pagesResearch Project Title: "AntiqueñoTam MiNo ratings yet

- 3 Financial Planning Strategies For Women - Attendee ReportDocument22 pages3 Financial Planning Strategies For Women - Attendee ReportMadeleine HarrisNo ratings yet

- Ceragon RFU-C Product DescriptionDocument45 pagesCeragon RFU-C Product DescriptionGeiss Hurlo BOUKOU BEJELNo ratings yet

- Meenaperfumery Shopping CartDocument4 pagesMeenaperfumery Shopping Cartzakir84md3639No ratings yet

- Merrill LynchDocument18 pagesMerrill LynchVikas Singhal0% (2)

- Suppliers, Manufacturers, Exporters & Importers 07022021Document1 pageSuppliers, Manufacturers, Exporters & Importers 07022021constas40No ratings yet

- DR-638HE: Dual-Band Mobile Transceiver With Full Duplex CapabilityDocument2 pagesDR-638HE: Dual-Band Mobile Transceiver With Full Duplex CapabilityChris GuarinNo ratings yet

- VSLA Linkage With MFDocument46 pagesVSLA Linkage With MFSamuel Dawit RimaNo ratings yet

- Bank Statement SantoniDocument1 pageBank Statement SantoniBinance Cutie0% (1)

- Asmi-52: 2/4-Wire SHDSL Modem/MultiplexerDocument6 pagesAsmi-52: 2/4-Wire SHDSL Modem/Multiplexerhotrokythuat SNTekNo ratings yet

- Compilation Report ICAI FinalDocument3 pagesCompilation Report ICAI FinalCA Dnyaneshwar Hase0% (1)

- GSM FundaDocument101 pagesGSM FundaPradipta BhattacharjeeNo ratings yet

- Computer NetworkingDocument4 pagesComputer Networking11D 06 AYONTI BISWASNo ratings yet

- Budgeting FormDocument6 pagesBudgeting FormMaritim LifeNo ratings yet

- Nabeel Sayed MBA FINAL PROJECT REPORRT (1) 2su18av804Document92 pagesNabeel Sayed MBA FINAL PROJECT REPORRT (1) 2su18av804Sijal KhanNo ratings yet

- Tranzum Courier ServiceDocument23 pagesTranzum Courier ServiceNoman ahmedNo ratings yet

- Reliance PDFDocument44 pagesReliance PDFDipanshu NagarNo ratings yet

- Analisis PT Bib 2011Document168 pagesAnalisis PT Bib 2011raditya wpNo ratings yet