Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BP-Econ Appeal Brief FINAL (Filed) 9-3-2013

Uploaded by

Simone SebastianCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BP-Econ Appeal Brief FINAL (Filed) 9-3-2013

Uploaded by

Simone SebastianCopyright:

Available Formats

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 1

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

No. 12-31155 c/w No. 13-30095 _____________________________________________________________ UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT ______________________________________________________________ IN RE: DEEPWATER HORIZON APPEALS OF THE ECONOMIC AND PROPERTY DAMAGE CLASS ACTION SETTLEMENT _____________________________________________________________ LAKE EUGENIE LAND & DEVELOPMENT, INCORPORATED; BON SECOUR FISHERIES, INCORPORATED; FORT MORGAN REALTY, INCORPORATED; LFBP 1, L.L.C., DOING BUSINESS AS GW FINS; PANAMA CITY BEACH DOLPHIN TOURS & MORE, L.L.C.; ZEKES CHARTER FLEET, L.L.C.; WILLIAM SELLERS; KATHLEEN IRWIN; RONALD LUNDY; CORLISS GALLO; JOHN TESVICH; MICHAEL GUIDRY, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED; HENRY HUTTO; BRAD FRILOUX; JERRY J. KEE, Plaintiffs Appellees v. BP EXPLORATION & PRODUCTION, INCORPORATED; BP AMERICA PRODUCTION; BP PIPELINE COMPANY, Defendants Appellees v. GULF ORGANIZED FISHERIES IN SOLIDARITY & HOPE, INCORPORATED, Movant Appellant _____________________________________________________________ On Appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana C.A. Nos. 2:10-md-2179, and 2:12-cv-970 ___________________________________________________________ PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES BRIEF ON THE MERITS ___________________________________________________________

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 2

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Stephen J. Herman Herman, Herman & Katz LLC 820 OKeefe Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana 70113 Telephone: (504) 581-4892 Fax No. (504) 569-6024 E-Mail: sherman@hhklawfirm.com Lead Class Counsel

James Parkerson Roy Domengeaux, Wright, Roy, & Edwards LLC 556 Jefferson Street, Suite 500 Lafayette, Louisiana 70501 Telephone: (337) 233-3033 Fax No. (337) 233-2796 E-Mail: jimr@wrightroy.com Lead Class Counsel

Samuel Issacharoff 40 Washington Square South, 411J New York, NY 10012 Telephone: (212) 998-6580 E-Mail: si13@nyu.edu Counsel on the Brief

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 3

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS The undersigned counsel of record for Appellees certify that the Certificate of Interested Persons as set forth by Appellants in their Briefs is complete. Undersigned are not aware of any other interested persons under Fed. R. App. Proc. 28.2.1.

/s/ Stephen J. Herman and James Parkerson Roy Co-Lead Class Counsel

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 4

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT Pursuant to Fifth Circuit Rule 28.2.4, Class Counsel respectfully submits that oral argument will likely assist the Court in resolving the issues presented in this appeal.

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 5

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents . Table of Authorities Statement of Facts .

. . .

. . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

i iv 1 1 7 9 10 12 12 14 15 17 20 21 22 27

A. Factual Background . B. Procedural Background

C. Overview of the Approved Settlement 1. Claims Categories . .

2. Transparency, Objectivity and Independence 3. Structural and Procedural Safeguards 4. Protections Against Future Risk . . . . .

5. Basic Compensation Frameworks . 6. Seafood Compensation Program .

7. Assignment and Other Class-Wide Relief . 8. The Objectors . Summary of the Argument Standard of Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 6

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Argument

28

I. The Pentz Appellants Arguments Are Unsupported, Fail to Address Their Own Claims, and Request Nothing More Than Remand to The District Court . . . . . . . . . II. The Coon and GO FISH Appellants Have No Standing . . .

28 35

A. The Coon Appellants Lack Standing for Failure to Meet the District Court Filing Requirements . . . . B. GO FISH Lacks Standing for Both Substantive and Procedural Reasons . . . . . .

36

37

III. The Coon Appellants Arguments Demonstrate a Fundamental Misunderstanding of the Common Objective Guiding Principles of the Settlement . . . . . . . . A. The Common Source of Class Members Damages Support Commonality, Predominance, and the Superiority of the Class Action to Resolve their Claims . . . 1. Commonality . . . . . . . .

43

. . .

43 45 48

2. Common Issues Predominate Over Individual Issues

3. The Class Action is Superior to Other Available Methods for the Comprehensive Determination and Resolution of Claims in This Litigation . . . . .

53

B. Class Counsel Were and Are Qualified to Manage the Settlement Class Without Conflicts . . . . . . . C. Notice and Opt-Out Procedures Satisfied Rule 23(e) and Contemporary Best Practices . . . 1. The Settlement Notice . . . . .

56

. .

. .

58 58

2. Notice Does Not Include The Obligation to Create an Opt Out Form . . . . . . .

ii

60

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 7

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

3. Due Process is protected by having Claimants Themselves Sign the Opt-Outs . . . . . . IV. The Palmer Appellants Arguments Concerning Real Property Damage Claims, Cy Pres, and Attorneys Fees are Fundamentally Flawed . . . . . . . . . A. The Coastal Real Property Class Representatives are Adequate B. There Is No Cy Pres in This Settlement . C. The Settlement Was Not Fee-Driven . . . . . . .

61

. . . .

62 63 67 69

V. The Bacharach Appellants Arguments Were Never Raised Before the District Court and Are Nonetheless Irrelevant to an Uncapped Settlement . . . . . . . Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .

72 78 82 83 84

Certificate of Compliance with Type-Volume Limitations. Certificate of Electronic Compliance . Certificate of Service . . . . . . . . .

iii

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 8

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) In re Airline Ticket Commn Antitrust Litig., 307 F.3d 679 (8th Cir. 2002) . . . . . .

. .

. .

67 52

Allapattah Services v. Exxon Corp., 333 F.3d 1248 (11th Cir. 2003) Amchem Products v. Windsor, 521 U.S. 591 (1997) . .

. 41, 49, 66

In re AOL Time Warner ERISA Litig., 2007 WL 4225486 (S.D.N.Y. 2007) . . . . . . Ayers v. Thompson, 358 F.3d 356 (5th Cir. 2004) . Balentine v. Thaler, 626 F.3d 842 (5th Cir. 2010) . . .

. . .

. . . .

. . . .

28 10 72 51

Bateman v. Am. Multi-Cinema, Inc., 623 F.3d 708 (9th Cir. 2010) Blatt v. Dean Witter Reynolds Intercapital, Inc., 732 F.2d 304 (2d Cir. 1984) . . . . . . .

. .

70 71

In re Bluetooth Headset Prod. Liab. Litig., 654 F.3d 935 (9th Cir. 2011). Butler v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., ___ F.3d ___, 2013 WL 4478200 (7th Cir. Aug. 22, 2013) . . . . . . Castano v. Am. Tobacco Co., 84 F.3d 734 (5th Cir. 1996) . Central States v. Merck-Medco, 504 F.3d 229 (2d Cir. 2007) Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 133 S.Ct. 1426 (2013) . Dennis v. Kellogg Co., 697 F.3d 858 (9th Cir. 2012) . . . . . .

. 49, 53, 76 . . . . . . . . . . . 50 66 53 69 62 50

In re Diet Drugs Prods. Liab. Litig., 282 F.3d 220 (3d Cir. 2002)

Evon v. Law Offices of Sidney Mickell, 688 F.3d 1015 (9th Cir. 2012). .

iv

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 9

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Feder v. Electronic Data Sys. Corp., 248 Fed.Appx. 579 (5th Cir. 2007) . . . . . . In re FEMA Trailer Formaldehyde Products Liab. Litig. (Mississippi Plaintiffs), 668 F.3d 281 (5th Cir. 2012)

37

. . .

. . .

72 62 61

Gemelas v. Dannon Co., 2010 WL 3703811 (N.D. Ohio 2010) . Hanlon v. Chrysler Corp., 150 F.3d 1011 (9th Cir. 1998) . See In re: Foodservice, Inc., Pricing Litig., No. 12-1311, ___ F.3d ___ (2d Cir. Aug. 30, 2013) . . . In re Holocaust Victim Assets Litigation, No.96-4849,51 2000 WL 33241660, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 20817 (Nov. 22, 2000), affd, 413 F.3d 183 (2d Cir. 2005) .

49

51

In re Initial Public Offering Securities Litigation, 721 F.Supp.2d 210 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) . . . . . . . . In re Insurance Brokerage Antitrust Litigation, 579 F.3d 241 (3d Cir. 2009) . . . . . . Juris v. Inamed Corp., 685 F.3d 1294 (11th Cir. 2012), cert. denied, 133 S.Ct. 940 (2013) . .

28

52

. . .

41

In re Katrina Canal Breaches Litig., 628 F.3d 185 (5th Cir. 2010) Klier v. Elf Atochem N. Am., Inc., 658 F.3d 458 (5th Cir. 2011) Mangone v. First USA Bank, 206 F.R.D. 222 (S.D. Ill. 2001) .

29, 42 67, 69 . 68

. . .

Maywalt v. Parker & Parsley Pet. Co., 67 F.3d 1072 (2d Cir. 1995) In re Monumental Life Ins. Co., 365 F.3d 408 (5th Cir. 2004) .

26, 70 . 27

Mullen v. Treasure Chest Casino, LLC, 186 F.3d 620 (5th Cir. 1999) . In re Nassau County Strip Search Cases, 461 F.3d 219 (2d Cir. 2006) .

v

27, 45 47

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 10

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Newby v. Enron Corp., 394 F.3d 296 (5th Cir. 2004)

. . . .

. . . .

. .

73 27

Pederson v. La. State Univ., 213 F.3d 858 (5th Cir. 2000) . Petrovic v. Amoco Oil Co., 200 F.3d 1140 (8th Cir. 1999) Phillips Petroleum Co. v. Shutts, 472 U.S. 797 (1985) .

41, 53 . 60

In re Prudential Ins. Co. of Am. Sales Practices Litig., 148 F.3d 283 (3d Cir. 1998) . . . . . . . Puffer v. Allstate Ins. Co., 675 F.3d 709 (7th Cir. 2012) . .

. .

. .

70 73

In re Royal Ahold N.V. Sec. & ERISA Litig., 461 F.Supp.2d 383 (D. Md. 2006) . . . . . . . Seijas v. Republic of Argentina, 606 F.3d 53 (2d Cir. 2010) Silverman v. Motorola Solutions, Inc., ___ F.Appx ___, 2013 WL 4082893 (7th Cir. Aug. 14, 2013) . . Strong v. Bellsouth Telecommunications, Inc., 137 F.3d 844 (5th Cir. 1998) . . . . . . .

. .

. .

28 47

38

71

Sullivan v. DB Investments, Inc., 667 F.3d 273 (3d Cir. 2011), cert. denied, 132 S. Ct. 1876 (2012) . . . . In re TFT-LCD (Flat Panel) Antitrust Litig., 289 F.R.D. 548 (N.D. Cal. 2013) . . . . . . Taubenfeld v. AON Corp., 415 F.3d 597 (7th Cir. 2005) . Tolbert v. LeBlanc, 512 F. App'x 401 (5th Cir. 2013) .

41, 49, 55, 56

. . .

. . .

62

28, 72 . 73

Union Asset Mgmt. Holding A.G. v. Dell, Inc., 669 F.3d 632 (5th Cir. 2012) . . . . . . U.S. ex rel. Mathews v. HealthSouth Corp., 332 F.3d 293 (5th Cir. 2003) . . . . . .

vi

. 27, 52, 71

38

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 11

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

U.S. ex rel. Willard v. Humana Health Plan of Tex., Inc., 336 F.3d 375 (5th Cir. 2003) . . . .

38

In re Visa Check-MasterMoney Antitrust Litigation, 280 F.3d 124 (2d Cir. 2001) . . . . . . . Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 131 S.Ct. 2541 (2011) . .

. .

51

45, 53

In re Wal-Mart Wage and Hour Employment Practices Litig., MDL No. 1735, 2010 WL 786513 (D. Nev. 2010) . In re Warfarin Sodium Antitrust Litigation, 391 F.3d 516 (3d Cir. 2004) . . . . . .

28

. . .

49 70 60

Waters v. Intl Precious Metals, Corp., 190 F.3d 1291 (11th Cir. 1999) . Wortman v. Sun Oil Co., 755 P.2d 488 (Kan. 1987) . . .

Young v. Nationwide Mutual Insurance Co., 693 F.3d 532 (6th Cir. 2012) . . . . . . Oil Pollution Act of 1990, 33 U.S.C. 2701 et. seq. 33 U.S.C. 2702 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

60, 61 . . . . . . . . . 51 22 47 47 47 47 22 32 32

33 U.S.C. 2703(a)(3) 33 U.S.C. 2704(a) 33 U.S.C. 2704(c)(1) 33 U.S.C. 2705(a) 33 U.S.C. 2713 33 U.S.C. 2717(f) 33 U.S.C. 2717(h) .

vii

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 12

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

American Law Institute, Principles of the Law of Aggregate Litigation, 1.03 (2010) . . . . . . . . Class Action Notices Page, THE MANUAL FOR COMPLEX LITIGATION, FOURTH (Federal Judicial Center 2004) . . . . Samuel Issacharoff and Theodore Rave, The BP Oil Spill Settlement and the Paradox of Public Litigation, http://ssrn.com/abstract=2278378 .

55

60

35

viii

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 13

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

STATEMENT OF FACTS 1 A. Factual Background

On April 20, 2010, a blowout, explosion, and fire occurred aboard the Deepwater Horizon drilling vessel as it was preparing to conclude operations on BPs Macondo Well on the Outer Continental Shelf off the coast of Louisiana. The Deepwater Horizon Incident resulted in eleven deaths, multiple injuries, and a massive discharge of oil into the Gulf of Mexico that continued for 87 days.2 The Incident disrupted economic activity in the Gulf region for many months. Numerous individual and class claims of property damage and economic loss were filed in the Federal Courts of the Gulf States. The District Court took early charge of the case, and, on August 10, 2010, the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation assigned all federal cases to the

Record cites will generally contain both the District Court Document Number and this Courts Record Cite as [Dist. Ct. record; Fifth Cir. record]. Where the material is included in Appellees Record Excerpts, the R.E. cite will come first: [Record Excerpt page; Dist. Ct. record; Fifth Cir. record]. Capitalized terms are generally used as they are defined in the Economic and Property Damages Settlement Agreement [Rec. Doc. 6430-1; 6261]. 2 The Settlement Agreement defines the Deepwater Horizon Incident as the events, actions, inactions and omissions leading up to and including (i) the blowout of the MC252 Well; (ii) the explosions and fires on board the Deepwater Horizon on or about April 20, 2010; (iii) the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon on or about April 22, 2010; (iv) the release of oil, other hydrocarbons and other substances from the MC252 Well and/or the Deepwater Horizon and its appurtenances; (v) the efforts to contain the MC252 Well; (vi) Response Activities, including the VoO Program; (vii) the operation of the GCCF; and (viii) BP public statements relating to all of the foregoing. ECONOMIC AND PROPERTY DAMAGES SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, at 100, 38.43 [Rec. Doc. 6430-1; 6360].

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 14

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

District Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1407.3 Since that time, the District Court has actively managed all Macondo-related actions asserting claims (primarily under maritime law and the Oil Pollution Act) by and on behalf of those whose businesses, livelihoods, properties, and lives have been affected by the Deepwater Horizon Incident, including Transoceans Limitation Action and the individual suits, class actions, and joinders filed in the Eastern District of Louisiana and other districts. On October 19, 2010, the District Court issued Pre-Trial Order No. 11 [Rec. Doc. 569; 1413], organizing the pleadings and categorizing the claims and issues by creating pleading bundles for various types of claims. The B1 bundle

encompasses all private claims for economic loss and property damage [PTO 11, III(B1)]. The Plaintiffs Steering Committee (PSC) filed the original B1 Master Complaint on December 15, 2010 [Rec. Doc. 879; 1439], and a First Amended B1 Master Complaint on February 9, 2011 [Rec. Doc. 1128; 1938]. Numerous

Defendants filed motions to dismiss, and, on August 26, 2011, the District Court issued an Order and Reasons granting in part and denying in part these motions [Rec. Doc. 3830; 2139].4

See In re Oil Spill By The Oil Rig Deepwater Horizon in the Gulf of Mexico, on April 20, 2010 (MDL No. 2179), 731 F.Supp.2d 1352 (J.P.M.L. 2010). 4 These Order and Reasons (8/26/2011) [Doc 3830; 2139] are reported at In re Oil Spill by the Oil Rig Deepwater Horizon, 808 F.Supp.2d 943 (E.D. La. 2011).

3

BP answered the First Amended Complaint on

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 15

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

September 27, 2011 [Rec. Doc. 4130; 2178]. Phase One of a multi-phase common issues trial centered around Transoceans Limitation Action (No. 10-2771) was conducted from February 25 to April 17, 2013. Phase Two of the common issues trial, focusing on quantification (how much oil escaped from the Macondo well) and source control (why did it take 87 days for BP to close the well), will commence on September 30, 2013 and is scheduled to last approximately four weeks. Following the JPMLs centralization order, the parties engaged in extensive discovery and motion practice to prepare for the multi-phase trial. They took over 390 depositions, produced approximately 120 million pages of documents, and exchanged more than 80 expert reports, on the intense and demanding schedule appropriately set by the District Court to keep this massive litigation on course. Depositions were conducted on simultaneous multiple tracks, on two continents. Discovery was managed and kept on schedule by weekly discovery conferences before Magistrate Judge Shushan and by monthly status conferences held by the Court. In February 2011, against this backdrop of intensive discovery and pretrial proceedings, the parties began to explore settlement opportunities. Given the nature and extent of the claims, the mutually perceived need for ongoing judicial

3

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 16

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

supervision, and the procedural due process protections unique to Rule 23, the class action was selected early on as the most appropriate structure for any comprehensive resolution. Settlement discussions intensified in July 2011,

thereafter occurring on an almost-daily basis. In late 2011, Magistrate Judge Shushan became involved in the settlement negotiations, at the request of the parties and designation by the Court. In all, over 145 day-long, face-to-face

negotiation meetings took place, in addition to numerous phone calls and WebEx conferences.5 In negotiating the Settlement Agreement, the parties followed a rigorous protocol: rather than negotiating a total settlement figure for an aggregate class settlement, the parties determined, at arms length, the strength and value of each separate type of claim. Without regard to the potential total payout figures, the parties negotiated these specific claims frameworks, programs, and processes, including the types of documentation or other proof that would be required for claimants to receive a settlement benefit, what categories of claims would be paid, whether certain claimants would benefit from causation presumptions, and how settlement benefits would be calculated.6 The negotiations were exclusively

See Transcript, at 83 (April 25, 2012) [Rec. Doc. 6395; 5802].

See generally Declaration of John C. Coffee, Jr. (Coffee Declaration) (submitted

jointly by BP and Class Counsel), 26-28 [Rec. Doc. 7110-3; 10243]; Declaration of Geoffrey P. Miller (Miller Declaration) (submitted by BP), 22-27 [R.E. 5.006; Rec. Doc. 7114-16;

4

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 17

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

focused, from the outset, on producing claims frameworks that could be administered fairly, objectively, transparently, and consistently, based on the merits of the underlying claims.7 During this process, PSC members and other Plaintiffs counsel familiar with each of the claims were consulted by the negotiators to help ensure that the frameworks reflected the actual situations faced by people and businesses affected by the spill. For example, attorneys representing seafood restaurants contributed to the development of the business economic loss framework, which details the steps by which businesses recover for losses due to the spill. So, too, did attorneys representing employees inform the development of the individual lost wages framework; attorneys representing wetlands owners the property damage framework; attorneys representing homeowners the real estate sales loss framework; and so on.8

10737]; Herman Declaration [Rec. Doc. 7104-5; 9908]; Rice Declaration (Negotiations) [Rec. Doc. 7104-6; 9913]; Issacharoff Decl. 7-14 [Rec. Doc. 7104-4; 9895]. 7 A major goal of the settlement was to address and correct widespread claimant dissatisfaction with the Gulf Coast Claims Facility (GCCF), a program established and conducted by BP outside court auspices. See Order and Reasons (Feb. 2, 2011) [Rec. Doc. 1098; 1923]. 8 Appellants raise the potential allocation question hypothetically faced by Class Counsel: should the compensation for one subclass be raised and correspondingly that for another lowered? Palmer Appellants Br., at 28-29 (quoting Coffee, Class Wars 95 Colum. L. Rev. 1343, 1443 (1995)). Yet, that type of decision was never made during these negotiations. Rather, the Parties were careful to ensure that Class Counsel were never placed in a position of having to make that type of trade-off. And Class Counsel never did. See generally Coffee Declaration 23-34 [Rec. Doc. 7110-3]; Herman Declaration [Rec. Doc. 7104-5; 9908];

5

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 18

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

With the exception of the Seafood Compensation Program, there is no limit or cap on the amount to be paid by BP under these frameworks. Rather, all claims that meet the criteria will be paid in full. Claimants may submit claims in multiple categories to recover on all demonstrable losses arising from the Deepwater Horizon Incident. The Seafood Fund has a guaranteed sum of

$2.3 billion, a figure representing more than four times the total yearly seafood revenues in the entire Gulf, allocated by a court-appointed neutral.9 On February 26, 2012, the literal eve of the Limitation and Liability Trial, the Court adjourned proceedings for one week, at the parties request, to enable further progress on the settlement talks. [Rec. Doc. 5887; 3459.] On March 2, 2012, the Court was informed that the parties had reached an Agreement-inPrinciple on the proposed settlements. The Court adjourned Phase I of the trial, because of the potential for realignment of the parties and potential changes to the trial plan. [Rec. Doc. 5955; 3460.]

Rice Declaration (Negotiations) [Rec. Doc. 7104-6; 9913]; Issacharoff Declaration 7-17 [Rec. Doc. 7104-4; 9895]; Miller Declaration 22-28 [R.E. 5.006; Rec. Doc. 7114-16; 10737]. 9 Mr. Perry was appointed by court order. [Rec. Doc. 5998; 3492.] The detailed 85-page Seafood Compensation Program he developed can be found as EXHIBIT 10 to the SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT [Doc 6276-22; 4390] (amended at REC. DOC. 6415-5; 6139).

6

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 19

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

B.

Procedural Background

While work continued finalizing the details of the settlement, the Court entered, at the parties request, an Order facilitating a transition from the GCCF to the Court Supervised Settlement Program, and appointed a Transition Coordinator and Claims Administrator. [Rec. Doc. 5995; 3487.] On April 16, 2012, the PSC filed a new class action complaint to serve as the vehicle for the proposed Economic and Property Damage Settlement. This action, Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc., et al. v. BP Exploration & Production Inc., et al., was amended on May 2, 2012 [Rec. Doc. 6412; 5854]. On April 18, 2012, the PSC and BP filed the proposed Economic Settlement [Rec. Doc. 6276; 4008] and Motions for Preliminary Approval and Class Certification [Rec. Doc. 6266; 3554] [Rec. Doc. 6269; 3908] [Rec. Doc. 6414; 6000], which were granted, after a multi-hour preliminary approval hearing conducted on April 25, 2012.10 On November 8, 2012, after extensive notice, the District Court conducted the fairness hearing. Numerous expert reports, declarations, exhibits, and

extensive briefing were submitted by Class Counsel and BP. These included expert declarations addressing the interrelated issues of class certification and settlement approval submitted by BPs expert Geoffrey P. Miller, Plaintiffs expert

10

See Preliminary Approval Order (May 2, 2012) [Rec. Doc 6418; 6208].

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 20

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Robert H. Klonoff, and the parties joint expert, John C. Coffee, Jr.11 The District Court heard extensive argument from BP, Class Counsel, and the objectors. At the time, the District Court had before it the best objective indicia of whether the Class was objectively defined with predominantly common issues of law and fact subject to a superior procedural mechanism for claim resolution i.e. the operation of the Settlement Program, which had been accepting, processing, and paying claims for five months. BP was thrilled with the manner in which the claims were being processed, as its counsel Richard Godfrey represented: The settlement is working as we anticipated. [Rec. Doc. 7892 at 62; 15736.] BPs Counsel also noted that, in reaching the Class Settlement Agreement, BP and the Plaintiff Steering Committee: [w]ent out and retained the nations leading legal experts, Professors Coffee, Miller, Klonoff and Issacharoff. * * *

They have provided the Court with their own declarations on both the structure, the propriety, the analysis under class action law, and the fairness, reasonable and adequacy of the settlement. Those declarations are well worth considering because these are our nations leading experts in this field.12

The District Court attached an index of all declarations to its decision, [R.E. 1.117; Rec. Doc. 8138, at 117; 19962], as well as another index that identified the Class Definition, id. at 119-25 [R.E. 1.119-25; 19964]. 12 Fairness Hearing Transcript, at 52 [Rec. Doc. 7892; 15726].

11

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 21

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

On November 19, 2012, BP and Class Counsel submitted detailed joint proposed findings on each element of settlement approval and class certification, referencing their respective and joint experts, and the operation of the Settlement Program.13 On December 21, 2012, the District Court issued its 116 page Order and Reasons, [R.E. 1.001; Rec. Doc. 8138; 19846] and its 15 page Order and Judgment [R.E. 2.001; Rec. Doc. 8139; 19971] certifying the Settlement Class and granting full approval to the settlement. The decision extensively reviewed the factual and procedural history, id. at 1-5, provided an overview of the Settlement, id. at 6-19, addressed the Rule 23(a) and (b)(3) criteria, id. at 24-55, determined the Settlement was fair, reasonable and adequate, id. at 55-74, and overruled each of the Objectors arguments, id. at 74-116. C. Overview of the Approved Settlement

The Settlement is designed to resolve claims by private individuals and businesses for economic loss and property damage resulting from the Deepwater Horizon Incident. The Economic Loss and Property Damage Settlement Class certified for settlement purposes pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure

13 Class Counsels and BP Defendants Joint Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law in Support of Final Approval of Deepwater Horizon Economic and Property Damages Settlement, etc. [Rec. Doc. 7945; 16008]. The joint submission includes 44 pages of proposed findings regarding the satisfaction of Rule 23(a)(1)-(4) and (b)(3) requirements.

9

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 22

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

23(b)(3), consists of individuals and entities defined by (1) geographic bounds and (2) the nature of their loss or damage.14 If both criteria are not met, or the plaintiff opts out, that individual or entity is not within the settlement class and the claims are completely unaffected by the Settlement. Where a person or entity has

multiple claims, some falling within the settlement and some falling outside of the settlement, only the former claims are included. In several cases, claims falling outside of the Settlement are Expressly Reserved.15 The class is objectively defined by geographic bounds: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and certain coastal counties in eastern Texas and western Florida, as well as specified adjacent Gulf Waters, such as estuaries, inlets and bays. Individuals must have lived, worked, owned property, leased property, etc., in these areas between April 20, 2010 and April 16, 2012. Entities must have conducted certain business activity in these areas between April 20, 2010 and April 16, 2012.16 1. Claims Categories

The Settlement, described in detail in the District Courts Final Approval Order and Reasons recognizes six basic categories of damage:

14

The Class Definition is incorporated as Appendix A to the Order of Judgment [R.E.

2.007-13; Rec. Doc. 8139, at 7-13; 19977]. 15 See generally SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 3, 8.2.3 & 10.2 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4027]. 16 See generally Order of Judgment Appendix A [R.E. 2.007-13; Rec. Doc. 8139, at 7-13; 19977].

10

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 23

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

(1)

Economic Loss (including frameworks for individual loss of wages,

business economic loss, multi-facility businesses, start-up businesses, failed businesses, and failed start-ups) (2) Property Damage (including frameworks for coastal property,

wetlands, and realized sales losses) (3) (4) (5) (6) Vessel of Opportunity (VoO) Charter Payment Claims Vessel Physical Damage and Decontamination Subsistence Commercial Fishing Losses (i.e. the Seafood Compensation Program)

Certain individuals, entities and claims are specifically excluded from the Settlement.17 Substantial claims are reserved to claimants, who can be compensated for their included claims under the Settlement while also preserving and pursuing the reserved claims outside of the Settlement Class. Class Members may submit multiple claims and receive compensation for multiple categories of damage.18

17

Exclusions from the Economic Class Definition are listed in Section 2 of the Settlement

Agreement, (e.g., casinos, banks, real estate developers, and members of the oil and gas industry). The rights of these excluded claimants are unimpaired, as their economic loss claims may continue to be prosecuted in this litigation or elsewhere. 18 See SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 4.4.8 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4038].

11

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 24

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

2.

Transparency, Objectivity, and Independence

Regarding the importance of objective and transparent criteria for class inclusion and claim compensation, and the shortfalls of the GCCF, the District Court observed: Full disclosure concerning the relationship between the responsible party and the third party acting in accordance with OPA is consistent with the policy underlying other court-overseen claims resolution facilities such as class actions or other settlement funds and bankruptcy trusts and is consistent with the transparency policies of many defendants. The legitimacy of a third-party claims-resolution facility is derived in no small part from the claimants ability to learn, comprehend, and appreciate how that facility is operated so that the claimants can fully evaluate the rationale behind the communications made to them by the facility. Full disclosure and transparency can insure that the reality of the operation of a third party will be consistent with any publicity concerning that entity. Full disclosure can also give protection to the responsible party from possible future legal attacks on the validity of the evaluation, payment, and release of claims.19 Judicial supervision of the settlement process under the formal structure of Rule 23 ensures that these objectives are realized throughout the claims process. 3. Structural and Procedural Safeguards

The Settlement Agreement contains a detailed series of objective frameworks and criteria, which were negotiated at arms length and shall apply

19

See Preliminary Approval Order and Reasons, at 7-8 [Rec. Doc. 6418; 6233].

12

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 25

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

equally to all Claimants under ongoing Court supervision,20 and overseen by an independent Claims Administrator with a fiduciary duty to the claimants.21 Per the Settlement: The Settlement Program, including the Claims Administrator and Claims Administration Vendors, shall use its best efforts to provide Economic Class Members with assistance, information, opportunities and notice so that the Economic Class Member has the best opportunity to be determined eligible for and receive the Settlement Payment(s) to which the Economic Class Member is entitled under the terms of the Agreement. SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 4.3.7 (emphasis supplied).22 The Claims Administrator Vendors shall evaluate and process the information in the completed Claim Form and all supporting documentation under the terms in the Economic Damage Claims Process to produce the greatest economic damage compensation amount that such information and supporting documentation allows under the terms . . . . SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 4.3.8 (emphasis supplied) [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4037].

See SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 4.4.7 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4037]. See also id. at 4.3.1 (providing for court appointment and supervision of the Claims Administrator); id. at 4.3.4 (providing the court with final dispute resolution authority of policy decisions); id. at 6.6 (providing the court with final dispute resolution to review appeals of claims); id. at 18.1 (providing the court with continuing jurisdiction over the Settlement). 21 See SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 4.3.1 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4037]. 22 See also SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 4.4.9 (providing that no negative presumption would apply to any claims previously denied by the GCCF); id. at 4.4.14 & 6.1.2.1.1 (providing that each class member is entitled to their entire claims file, including calculations and worksheets).

20

13

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 26

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

With the exception of the Seafood Compensation Program, (a guaranteed $2.3 billion fund), there is no limit on the amount to be paid by BP. Further, BP is responsible for satisfying the class members common benefit fee obligations, and reimburses claimants for accounting services required for the preparation and filing of their claims. BP provides a $57 million Gulf Coast Tourism and Seafood Promotional Fund, a Transocean insurance proceeds fund, and a $5 million supplemental publicity campaign, and assigns its claims against Transocean and Halliburton to the class. 4. Protections against Future Risks

In addition to baseline compensation payments, most claims also will receive a Risk Transfer Premium (or RTP), which is a multiple enhancement of the baseline compensation. RTPs range from .25 to 8.75, and are added to the baseline Compensation Amount, for an effective multiplier of 1.25 to 9.75 under the Proposed Settlement.23 The RTP enhancements are meant to compensate class members for pre-judgment interest, the risk of oil returning, consequential damages, inconvenience, aggravation, the risk of future loss, the lost value of money, the liquidation of legal disputes about punitive damages, and other factors.

See RTP Chart (Ex. 15) [Rec. Doc 6276-33; 4898]; Seafood Compensation Program (Ex. 10) [Rec. Doc 6276-22; 4390].

23

14

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 27

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

5.

Basic Compensation Frameworks

Individual economic losses under the Proposed Settlement are calculated as the estimated difference between a claimants expected earnings during May to December of 2010 and the claimants actual earnings during that claim period. To that base compensation amount is added any applicable RTP. Causation is presumed for claimants in geographic proximity to the spill, and for many tourism and seafood category claimants, whose losses from the spill are categorically more direct and less conjectural; other claimants must demonstrate that a loss is due to the oil spill based not on individualized, subjective, or inconsistent criteria, but on the objective criteria set forth under the terms of the settlement. For existing businesses, economic loss claims are determined using a twostep process. Step One calculates the value of the businesss reduction in profit during a claimant-selected loss period (any three or more consecutive months of the eight-month period following the spill). Step Two accounts for expected

profits by estimating the businesss growth trend along with a general, economywide growth factor. The sum of Step One (loss calculation) and Step Two

(expected profit but-for the spill) results in the business claimants base

15

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 28

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

compensation amount.24 This amount is generally enhanced by an RTP and/or offset by prior payments received, depending on the type of business and location. The Settlement also includes additional or alternative frameworks for multifacility businesses, failed businesses, start-up businesses, and failed start-up businesses. Coastal Real Property claimants are compensated for loss of use and enjoyment by multiplying the 2010 Applicable Property Tax (defined as 1.18% of the County Appraised Value) by 30%-45%, depending on the presence of oil and the environmental sensitivity of the property. This amount is enhanced by an RTP of 2.5. Additional compensation is available if claimants establish physical damage from response operations. Wetlands Real Property compensation is based on whether parcels were directly affected with oil. Oiled parcels are paid a minimum of $35,000 per acre. Where no oil was observed, compensation is a minimum of $4,500 per acre. Wetlands Real Property claims are enhanced by an RTP of 2.5. The Settlement provides compensation for certain individuals and entities that realized sales losses as a result of the spill. The compensation amount is 12.5% of the sale price.

There is currently pending before this Court a challenge by BP to the application of the business loss calculation, an issue not raised by any party at settlement approval or in the notices of appeal. See In re Deepwater Horizon, U.S. Fifth Circuit No. 30315.

16

24

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 29

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Subsistence claimants those individuals who fish, hunt, or harvest Gulf of Mexico natural resources to sustain the basic needs of themselves and their familiesare entitled to compensation for the total value of lost subsistence natural resources plus an RTP enhancement of 2.25. The Vessels of Opportunity (VoO) Charter Compensation provisions compensate those who chartered their vessels to assist with the cleanup, with 26 days of additional payments under the applicable rates provided in their charter agreements, while class members who executed charter agreements but were never formally dispatched receive three days of compensation at the applicable charter rate. Vessel owners whose vessels were physically damaged as a result of the oil spill or cleanup operations may recover the lesser of repair or replacement costs. 6. Seafood Compensation Program

The parties attempted to negotiate separate frameworks for commercial fishing and oyster leaseholder claims for a number of months. The lead

negotiators for the plaintiffs frequently consulted with other attorneys, stakeholders and industry representatives to gain insight and achieve consensus and support for the models being discussed with BP. While these frameworks, like the others, were being negotiated within the context of an uncapped or evergreen structure, the plaintiff negotiators, through the course of these discussions, came to have a

17

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 30

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

good understanding of the overall picture with respect to commercial fishing in the Gulf and the documented effects of the spill on the industry. When, therefore, BP moved the discussion to a non-reversionary fund that would satisfy all class commercial fishing claims, the $2.3 billion that BP was willing to guarantee to the seafood claimants was almost five times the entire revenue of annual catch landed in the Gulf Coast Areas, and significantly more than the total of the projected aggregate pay-outs under the separate shrimp, oyster harvester, oyster leaseholder and deckhand compensation models under discussion by the stakeholder constituencies.25 Given the negotiating dynamic, (in which Magistrate Judge Shushan was participating as an active mediator), and the available evidence,26 Class Counsel believed, as has become evident, that a

2.3 billion replaces the entire catch in affected areas of the Gulf of Mexico for seven years, buys a 15 year supply of fuel, ice and food for every affected vessel, and is 22 times the 2010 loss caused by the spill. Split fairly, the Seafood Program should be enough to protect fishermen even in the worst case situation, total fishery collapse. Objector GO FISH counsel Joel Waltzer, Statement to the Press (March 19, 2012) [Rec. Doc. 7104-1; 9789]. 26 The NOAA ALS data comparing averages for 2007-2009 with the average for 2010 and preliminary estimates for 2011 show a 16.5% decline in the volume of shrimp landings, a 23.85% decline in the volume of blue crab landings, a 34.39% decline in the volume of oyster landings, and a 14.66% decline in the volume of finfish landings. The Seafood Program developed by Mr. Perry, by comparison, compensates the plaintiff for an annual 35% loss of shrimp and blue crabs, an annual 40% loss of oysters, and an annual 25% loss of finfish. In terms of overall revenue, the Seafood Program would account for an approximate 480% loss to the industry, in annual terms. [Rec. Doc. 7104-1; 9789.]

25

18

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 31

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

guaranteed $2.3 billion fund would provide significantly more compensation to the class than could be achieved under frameworks separately negotiated with BP.27 Out of an abundance of caution, and in order to prevent any perception of potential intra-class conflict, the parties asked the Court to appoint noted mediator, John W. Perry, Jr., to determine the allocation. Mr. Perrys independent research and determinations lend further support to the conclusion that $2.3 billion is more than sufficient to fully compensate the participants in the Seafood Program.28 Specifically, the Seafood Compensation Program frameworks, which are themselves conservative, are projected to pay out an initial amount of approximately $1.9 billion, in full and fair compensation to the relevant class members, leaving an approximate $400 million reserve. In addition to this $400 million head room: (i) more than $700 million was already paid to commercial fishermen by the GCCF; (ii) BP assumes full responsibility for up to 17.5% opt-outs; and (iii) class members punitive damage claims, as well as the BP-assigned claims, against Transocean and Halliburton are reserved.29

See Herman Declaration, 11 [Rec. Doc. 7104-5; 9911]; Declaration of Joseph F. Rice (Seafood Program) [Rec. Doc. 7104-6; 9925]. 28 See Plaintiffs Exhibit A (in globo) re the Seafood Compensation Fund [Rec. Doc. 7104-1; 9789]; Declaration of John W. Perry, Jr. [Rec. Doc. 7110-5; 10299]; Declaration of Daniel J. Balhoff [Rec. Doc. 7110-2; 10217]. 29 See generally Perry Declaration [Rec. Doc. 7110-5; 10293]; Balhoff Declaration [Rec. Doc. 7110-2; 10217]; Herman Declaration, 11 [Rec. Doc. 7104-5; 9911]; Rice Declaration (Seafood Program) [Rec. Doc. 7104-6; 9925].

27

19

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 32

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Within the Seafood Compensation Program frameworks developed by Mr. Perry, captains and vessel owners are generally awarded a base compensation amount derived from historical benchmark earnings, taking into account the vessel size and predetermined cost factors, price increases, and loss factors generally experienced by the relevant species. With the exception of shrimpers who can elect an expedited (or reduced expedited) lump sum payment, these base compensation amounts for captains and vessel owners are enhanced with substantial RTPs. The Seafood Compensation Program provides for a per-acre compensation payment to oyster leaseholders, and a separate formula to compensate holders of Individual Fishing Quota (IFQ) shares. Finally, the

Program provides varying levels of compensation to crew members, based on the level and quality of their supporting documentation. 7. Assignment and Other Class-Wide Relief

Under the Settlement, BP pays compensatory damages (including those that might be attributed to the fault of Transocean or Halliburton), but at the same time allows the plaintiffs to continue to seek punitive damage recoveries from Halliburton and Transocean.30 The Settlement also assigns certain of BPs claims

SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 3.6 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4027]; id. at 10.2 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4027].

30

20

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 33

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

against Transocean and Halliburton to the class.31 BP additionally provides a $57 million fund to promote tourism and seafood on the Gulf Coast,32 and a fund of up to approximately $150 million in recoveries from Transocean insurance proceeds.33 8. The Objectors

Contrasted with over 200,000 class members who have filed claims into the Court-Supervised Settlement Program, only five groups of objectors from the District Court filed appellate briefs. None of them complain of their compensation calculations, identify what compensation they are entitled to under the Settlement, or define what other or greater compensation they believe they should receive. Of the six settlement claim categories, only one part of the property claim (coastal real property), and one aspect of the business claims is challenged on appeal. The Seafood Program draws but a single contingent and premature challenge that depends on the second round distribution, which has not yet occurred. None of the individual, subsistence, VoO, or vessel damage frameworks are directly challenged by any Appellant.

BP, for example, assigned its claims against Transocean and Halliburton relating to the repair, replacement and/or re-drilling of the Macondo Well, the costs BP incurred to control the well and/or to clean up the spill, and for punitive damages. SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, Exhibit 21, 1.1.3 [Rec. Doc. 6271-1; 4066]. 32 SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 5.13 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4027]. 33 SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, Exhibit 21, 1.1.4.2 [Rec. Doc. 6276-39; 4971].

31

21

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 34

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT The Deepwater Horizon Incident, the most devastating oil spill of modern times, is also the largest to have occurred since enactment of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA), 33 U.S.C. 2701 et. seq. BP early acknowledged its statutory status as OPA responsible party, which extends its potential liability for economic loss far beyond the limitations of traditional maritime law. OPA

provides a single statutory framework to determine the ultimate bounds of this liabilitythe predominant common question facing all claimantsbut of itself provides no automatic answer. Notably, OPAs statutory policy favors resolution, preferring an accelerated comprehensive settlement program be implemented as an alternative to seriatim litigation.34 The GCCF, BPs initial attempt, lacked the features of court authority: the consistency, transparency and predictability that class action settlements ensure. It provided immediate compensation to some affected parties, but proved unable to fulfill OPA objectives of final resolution on an equitable and consistent basis. The class settlement, by contrast, achieved negotiated answers to common questions, within a structure suited to fulfill OPA resolution policy. As BPs pre-class

settlement experience proved, the sheer scope of the disaster and its unprecedented

See 33 U.S.C. 2705(a) (The responsible party shall establish a procedure for the payment or settlement of claims for interim, short-term damages.).

22

34

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 35

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

impact on the Gulf economy generated a volume and variety of claims beyond the ability of informal or piecemeal settlements to address. Like the Deepwater Horizon Incident itself, this Settlement is historic in size and uniqueness. As of the latest official report to the District Court, approximately 200,000 claims had been filed, and 139,000 claim notices had been issued, including 53,300 eligibility notices totaling over $4.4 billion in determinations.35 $3.16 billion has actually been paid with an additional $1.15 billion remaining in the Seafood Compensation Fund.36 Nothing can better gage the fairness, reasonableness, and adequacy of a settlement than the track record developed over the past year. To achieve this feat, the District Court appointed an independent Claims Administrator who oversees over 150 accountants, an even larger administrative staff, and operates with a quarterly budget exceeding $100 million.37 Completion of the administration infrastructure was accomplished with less than a three month lead-time from the date of interim appointment (March 8, 2012) to the first day claims were accepted for processing (June 4, 2012). No matter how many claims from any of the different six claim categories are deemed payable, no claims compete against each other for payment. While the

35 36

Claims Administrator Status Report No. 12,at 10-11 [Rec. Doc. 11008]. Id. See also 11008-1 at 3. 37 [Rec. Doc. 11179.]

23

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 36

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Seafood Compensation Fund is the lone exception, its guaranteed fund of $2.3 billion has proven more than sufficient to meet the objective formulae used for payment. Against this backdrop stand a paltry few objectors who raise the narrowest of concerns, which are either speculative, irrelevant to the actual class and settlement structure, or contradicted by the record. For perspective purposes, over 69,000 business economic claims have been filed;38 while only two lawyers, representing less than 15 businesses, have objected, voicing only the narrowest of a single concern. However, not one

business has complained of the value or compensation method of these claims. No Appellant is challenging the methodology or fairness of the 32,282 individual claims, the 25,592 subsistence claims, the 8,468 VoO claims, or the 1,297 vessel claims that have been filed.39 The foundation that binds the Rule 23(a) prerequisites of numerosity, commonality, typicality, and adequacy with the Rule 23(b)(3) requirements of predominance and superiority is, at the end of the day, one of feasibility whether a district court can manage the class action in terms of functionality, with fairness and efficiency. Here, because this class is one for settlement purposes, its

38 39

Claims Administrator Status Report No. 12,at 10 [Rec. Doc. 11008]. Id.

24

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 37

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

feasibility and manageability is found in the settlement itself. And, because it has been in effect for 14 months, the Settlements manageability has been on full display. It has worked. Of the 200,000 claims that have been filed, Class

Members have only appealed 731 claims, less than 0.3%.40 The challenges by the Appellants are remarkably narrow. For example, not one of the Appellants states exactly what amount it believed would have been fair, as opposed to what the Settlement methodologies dictate. Not one of the Appellants argues that the Settlement is vague, subjective, or opaque. Each of the Appellants had the ability to calculate the value of their claim and decide whether to make a claim or opt out. In this historic settlement, in which the Settlement Program was fully operational for months before the opt-out deadline, some claimants had the opportunity to receive a determination letter prior to the opt-out date, and all could determine on a fully informed basis what course was in their best interest. The only claims that are specifically challenged business, property, and seafood are not even frontally challenged on the merits of the damage calculation or on causation. Even the challenge to the Seafood Program does not argue that it

40

Id., at 17.

25

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 38

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

unfairly or unreasonably compensates claims; just that everyone needs to wait for the second round distribution to cure whatever issues may or may not exist. The damage frameworks, developed over months of intense negotiation, objectively quantify the losses suffered in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon Incident in 2010, and in most cases add an RTP, which further compensates for unknown and future effects, punitive damage exposure, the time value of money, and other legal uncertainties. The differences within these frameworks, developed through arms-length negotiation, are rationally related to the relative strengths and merits of similarly situated claims.41 The causation presumptions are generally afforded to the types of business and/or geographical locations most likely to have been impacted by the spill, while the higher compensation offered through the RTPs are generally afforded to industries and locations which face the greatest risk of ongoing loss and/or are most likely to have claims for punitive damages.42

41 Magistrate Judge Shushan played an important supervisory role in facilitating and

mediating the agreement. Her evenhanded, daily (and often minute-by-minute) efforts throughout the last three months of negotiations strongly counsel in favor of approving the settlement. See, e.g., Maywalt v. Parker & Parsley Pet. Co., 67 F.3d 1072, 1079 (2d Cir. 1995) (The supervision of settlement negotiations by a magistrate judge, as occurred here, makes it less likely that . . . [class counsel have promoted] their own interests over those of the class). 42 The members of the settlement class will receive additional individualized and collective benefits, including: reimbursement of reasonable claims preparation expenses, SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, at 25 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4056]; a $57 million Gulf Tourism and Seafood Promotional Fund, id. at 51; the class-wide assignment of BPs claims against Transocean and Halliburton, id. at 75; the satisfaction by BP of all common benefit costs and fees, id. at 78; a Transocean insurance proceeds reserve fund, id. at 53; and an express reservation of punitive damage claims against Transocean and Halliburton, id. at 12.

26

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 39

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

STANDARD OF REVIEW This Court reviews class certification and settlement approval orders for abuse of discretion. Union Asset Mgmt. Holding A.G. v. Dell, Inc., 669 F.3d 632, 638 (5th Cir. 2012). The District Court maintains great discretion in certifying and managing a class action, Pederson v. La. State Univ., 213 F.3d 858, 866 (5th Cir. 2000), because the certification inquiry is an inherently fact-based endeavor best left to the trial courts inherent power to manage and control pending litigation, In re Monumental Life Ins. Co., 365 F.3d 408, 414 (5th Cir. 2004). An abuse of discretion occurs only when all reasonable persons would reject the view of the district court, Union Asset Mgmt., 669 F.3d at 638, or where the district court applied incorrect legal standards in reaching its decision, Mullen v. Treasure Chest Casino, LLC, 186 F.3d 620, 624 (5th Cir. 1999).

27

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 40

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

ARGUMENT I. The Pentz Appellants Arguments Are Unsupported, Fail to Address Their Own Claims, and Request Nothing More than Remand to the District Court. The Pentz Appellants brief is reflective of the flighty, irresponsible actions of habitual objectors, untethered to the realities of the cases they enter, with no responsibility for the welfare of the affected class.43 First, they argue that because Texas businesses are treated dissimilarly from some Louisiana businesses, the matter should be remanded for further explanation for the disparate treatment. Pentz Appellants Brief, at 10. Second, the Pentz Appellants question the District Courts evaluation of the Court Supervised Settlement as compared to the Gulf Coast Claims Facility (GCCF). Id. at 11-14.

43 See, e.g., In re Wal-Mart Wage and Hour Employment Practices Litig., MDL No.

1735, 2010 WL 786513 at *1 (D. Nev. 2010) (sanctioning Pentz and finding Pentz and associates have a documented history of filing notices of appeal from orders approving other class action settlements, and thereafter dismissing said appeals when they and their clients were compensated by the settling class or counsel for the settling class); In re: Initial Public Offering Securities Litigation, 721 F. Supp. 2d 210, 215 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) (sanctioning Pentz and finding Pentz and associates have engaged in a pattern or practice of objecting to class action settlements for the purpose of securing a settlement from class counsel); Taubenfeld v. AON Corp., 415 F.3d 597, 599 (7th Cir. 2005) (finding Pentz made unsupported conclusory assertions in class settlement objections); In re AOL Time Warner ERISA Litig., 2007 WL 4225486, at *3 (S.D.N.Y. 2007) (calling Pentzs arguments counterproductive and irrelevant or simply incorrect); In re Royal Ahold N.V. Sec. & ERISA Litig., 461 F. Supp. 2d 383, 386 (D. Md. 2006) (noting that Pentz is a professional objector who attached himself to a plaintiff and holding his objection not well reasoned and was not helpful); Barnes, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 71072 (same).

28

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 41

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Notably, the Pentz Appellants challenge neither the causation analysis nor the damages calculations. They make no claim that their compensation (or anyone elses) is inappropriate. Instead, Pentz relies on In re Katrina Canal Breaches Litig., 628 F.3d 185 (5th Cir. 2010), a limited fund settlement in which the proceeds were grossly insufficient, to argue that, as compared to other claimants, their compensation may be lower. Yet, in the context of an uncapped settlement, where no claimant is taking from another, the comparative value argument does not cut across Rule 23 pre-requisites or Rule 23(b)(3) standards. Simply put, the issue is simply whether that particular claim value is reasonable and fair. The Pentz Appellants never explain what more they should receive under the settlement (as weighed against the risks and delays of litigation). The Pentz Appellants contention that the class fares more poorly under the settlement than under the GCCF is wholly unsupported by the record.44 The District Court, with ample knowledge of the GCCFs operations and performance, found the opposite.45 At every level, the Settlement Program is demonstrably superior to the GCCF.

The Pentz Appellants also attempt to adopt the arguments BP raised in its appeal in No. 13-30315. Pentz Appellants Brief, at 14. Those issues are already fully addressed in the pending appeal, were never raised below to the District Court, and concern interpretation of a contract, not class certification issues. See, infra, discussion of Bacharach Appellants arguments. 45 Order and Reasons, at 51-55, 109-110 [R.E. 1.051-55, 1.109-110; Rec. Doc. 8138; 19896, 19954].

29

44

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 42

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

To begin with, the GCCF was a unique and solitary mechanism, designed and operated by BP. To the extent claims remained unresolved, there was no independent enforcement mechanism to ensure that the GCCF would actually comply with its own stated policies or the requirements of OPA. Hence, a courtsupervised settlement generally, and the Court Supervised Settlement Program in particular, are fundamentally different from the unilateral, unregulated and inherently limited BP Gulf Coast Claims Facility. This Settlement is also quantitatively superior to the GCCF in at least the following ways: $ Provides the class members with more flexible Benchmark Periods from which to establish loss and, where necessary, causation.46 $ Replaces a vague baseline loss of income (LOI) determination with concrete and objective methods to establish base compensation loss, under a two-step process that accounts for both (i) losses, as compared to benchmark earnings periods, and (ii) the difference between 2010 profit and what the business would have earned but for the spill. $ Identifies specific fixed versus variable costs to be applied in the compensation calculations.

In particular, the GCCF generally used 2008-2009 as a benchmark. See generally Plaintiffs Exhibit B to Motion for Final Approval [Doc 7104-2; 9798]. Under the Settlement Program, by contrast, class members can generally go back to 2007. In addition, class members have the flexibility to use different sets of benchmark months to establish Causation versus the months they use to establish the amount of Base Compensation Loss sustained.

30

46

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 43

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

$ Allows for causation presumptions based on industry and location, and, with respect to other class members, provides various alternative methods of establishing, by objective means, that the business or individual suffered a loss caused by the spill. $ Compensates class members for Coastal and Wetlands Property Damages, VoO Charter Compensation, Real Estate Sales Losses, and other damages which were not being compensated by GCCF.47 $ Includes RTP enhancements that are in virtually all cases equal to or greater than the multipliers under the GCCF stated methodology.48 $ Provides a multi-level internal appeals process with review by court-appointed panelists who are experienced mediators, attorneys and retired judges. $ Guarantees independence, transparency, Court supervision, consistent, objective and predictable treatment of similar claims, and no special deals. All of these points and many more form part of the district court record and are unaddressed by Pentz.49

Class Counsel had been informally advised that some property damages claims might have been recognized by the GCCF, but these claims were certainly not paid by the GCCF in any routine or systematic way. 48 In general, the GCCF claimed to apply a multiplier of two (i.e. an RTP of 1) to most claims. At some point, the GCCF announced that it would apply a multiplier of four (i.e. an RTP of 3) to shrimper, crabber and shrimp and crab processing claims. A multiplier of four (i.e. an RTP of 3) was generally applied to oyster harvesters, while at some point a Future Risk Multiple raging from 1 to 7 was to applied to oyster leaseholder income claims. See generally Plaintiffs Exhibit B to Motion for Final Approval [Rec. Doc. 7104-2; 9798]. Compare RTP Chart, Exhibit 15, [Rec. Doc. 6276-33; 4898] with Seafood Compensation Program, Exhibit 10, at 24, 30, 33, 34, 36, 38, 49, 61, 63 [Rec. Doc. 6276-22; 9798].

31

47

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 44

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

The Settlement is also qualitatively superior to GCCF in providing for the extension of time periods for presentment and filing. Specifically, a claim under OPA must generally be both presented and filed within three years. 33 U.S.C. 2713 and 2717(f).50 While plaintiffs will undoubtedly have various arguments based upon tolling theories, dates of accrual, and/or the discovery rule, prudence would dictate that all OPA claims would have been both presented and filed by April 20, 2013. While the GCCF announced that it would accept claims up until August 23, 2013, there was no enforcement mechanism to ensure that the GCCF would do so, no assurances that the submission of a claim, either before or after April 20, 2013, would constitute presentment under OPA,51 nor any assurances that GCCF claimants not fully compensated as of April 20, 2013 would thereafter be permitted to file claims in court (or with the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund) despite the threeyear statute of limitations.

See also Declaration of Jeffrey June, 31 [Rec. Doc. 7710-2; 14700] (The settlement provides substantially more compensation to commercial shrimpers than the GCCF offered, even after the GCCF increased its amounts.); Declaration of Robert Mosher, 21 [Rec. Doc. 7710-3; 14706] (The historical revenue model is a substantial improvement over the GCCF model.). 50 See also 33 U.S.C. 2717(h) (providing for three-year statute of limitations on claims for damages against the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund). 51 While BP formally stipulated that presentment to the GCCF would constitute presentment to BP as the Responsible Party, (Order (Oct. 22, 2010) [Rec. Doc. 594; 1431]), BP had never formally stipulated or conceded that a claim submitted to the GCCF would, in fact, constitute Presentment under OPA.

32

49

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 45

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Indeed, there is little reason to believe that the tens of thousands of claims that remained unresolved after eighteen months in the GCCF (and/or were perhaps yet to be filed when the Transition Order was entered on March 2, 2012) would have been resolved in the GCCF prior to April 20, 2013 if ever: $ As far back as April of 2011, the GCCF stated that it had paid or was in the process of paying every single legitimate individual and business claim where the claimant can document economic loss due to the oil spill.52 In June of 2011, Mr. Feinberg said that the process was winding down as the GCCF had already processed 80% of the claims.53 He further indicated that all of the claims that he considered to be eligible would be resolved by October 2011.54 As of November of 2011, the GCCF began to assume that claims from the Florida peninsula and

Exhibit D to Motion for Final Approval, [Giardina, Are Stall Tactics Delaying BP Payments? WLOX.com (April 20, 2011)] [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14964]. 53 Exhibit D to Motion for Final Approval, [GCCF Claims Process Winding Down Disenfranchised Citizen (June 1, 2011) [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14964] (citing Blackden and Mason, BPs Oil Victim Fund Closes Some Offices as it Pays Out Just a Fifth of the $20bn Total, Telegraph (5/29/11) [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14962] (Feinberg told The Telegraph that he does not believe there will be many more fresh claims and has processed more than 80pc of the claims submitted); see also Mason, BP Not Meeting Gulf of Mexico Spill Obligations, US Report Claims Telegraph (June 2, 2011) [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14966] (Mr. Feinberg is in the process of scaling back operations, closing eight regional offices.)]. 54 Exhibit D to Motion for Final Approval, [Hammer, Claims Czar Kenneth Feinberg Says Pace of Payments Quickens Times-Picayune (June 20, 2011)] [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14966].

33

52

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 46

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

Texas were not legitimate unless they were commercial fishing claims.55 $ The job was done at the time of the Transition.56

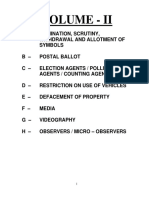

The Class Settlement allows Class Members to submit claims to the Court Supervised Settlement Program until April 22, 2014, or six months after finality, whichever is later.57 The Settlement further assures that submission of a claim to the Settlement Program will constitute presentment under OPA.58 Finally, the Settlement tolls the statute of limitations for class members until at least 90 days after the Settlement is terminated, should it be disapproved by the Court or terminated for any reason.59 Sometimes, one picture is worth a thousand words. The following summary chart, prepared by counsel for independent publication from the publicly available record, shows that at every level of compensation, Settlement recoveries are superior to the GCCF.

Exhibit D to Motion for Final Approval, [Hammer, Ken Feinberg Expands Oil Spill Claims Payments for Shrimpers, Crabbers Times-Picayune (Nov. 30, 2011)] [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14971]. 56 Exhibit D to Motion for Final Approval, [Shactman, Managing the BP Oil Spill Fund - No Small Task CNBC (4/19/12)] [Rec. Doc. 7727-3; 14972]. 57 SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 5.11.8 [Rec. Doc. 6276-1; 4056]. (The one exception to this is that all Seafood Program claims were to be submitted within 30 days of final approval in the District Court. Id. at 5.11.9.) In the event that the Class Settlement does not achieve final approval, the Settlement Program will continue to process and pay all claims submitted up to that point in time. Id. at 21.3. 58 Id. at 7.3.2; Stipulation [Rec. Doc 7130-1; 11210]. 59 SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT, 7.3.1.

34

55

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 47

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

12 10 8 6 4 4 2 2 0 2 2 2 4 4 3.25 2 9.75 9.25 8.25 7 7 7 6.5 6 MaximumGCCFMultiplier EffectiveClassMultiplier 44

5.5 3.25 3.5 2 2 2

3.5 2.25 2 2

2.5 2.25 2 2.125 2 2 1.25 2

This is not a conflict; this is a major achievement for the entire class.60 II. The Coon and GO FISH Appellants Have No Standing. Each group of Appellants failed to satisfy the reasonable procedural standing requirements imposed by the District Court to ensure that only class members submitted objections. The Coon Appellants failed to include proof of residency, property ownership, or business interest. GO FISH does not have standing because it is not an affected party and because the source of its complaint is speculative and not yet ripe.

60 The BP Oil Spill Settlement and the Paradox of Public Litigation, Samuel Issacharoff

and Theodore Rave, http://ssrn.com/abstract=2278378.

35

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 48

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

A.

The Coon Appellants Lack Standing For Failure to Meet the District Courts Filing Requirements.

The District Court ordered that any person or company that desired to object needed to provide: (a) a detailed statement of the Economic Class Members objection(s), as well as the specific reasons, if any, for each objection, including any evidence and legal authority the Class Member has to support each objection and any evidence the Class Member has in support of his/her/its objection(s); (b) the Economic Class Members name, address and telephone number; (c) written proof that the individual or entity is in fact an Economic Loss and Property Damage Class Member, such as proof of residency, ownership of property and the location thereof, and/or business operation and the location thereof; and (d) any other supporting papers, materials or briefs the Economic Class Member wishes the Court to consider when reviewing the objection. Any Class Member who fails to comply with these provisions shall waive and forfeit any and all rights to object to the Proposed Settlement, shall be forever foreclosed from making any objection to it, and shall be bound by all the terms of the Proposed Settlement and by all proceedings, orders and judgments in this matter.61 The Coon Appellants produced no proof of residency, ownership of property, or ownership of any business for their objectors. Instead, Mr. Coon filed an objection, purportedly on behalf of approximately 10,000 class members, but with only a list of people and businesses, some with addresses, others with phone

61

Preliminary Approval Order, 38 [Rec. Doc. 6418; 6246].

36

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 49

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

numbers, but none with proof of residency, proof of business ownership, or proof of property ownership. [Rec. Doc. 7224; 11716.] The Coon Appellants must have realized these deficiencies because they attempted to supplement the record the day before the Fairness Hearing. [Rec. Doc. 7863; 15634.] However, the District Court denied their late filing and struck whatever they were trying to supplement from the record. [Rec. Doc. 7870; 15645.] That order was not challenged on appeal. Failure to follow the District Court-imposed filing requirements results in a lack of standing to pursue this Appeal. Feder v. Electronic Data Sys. Corp., 248 Fed.Appx. 579, 581 (5th Cir. 2007) (unpublished) (finding a lack of standing where support of class membership was not provided because [a]llowing someone to object to a settlement in a class action based on this sort of weak, unsubstantiated evidence would inject a great deal of unjustified uncertainty into the settlement process). B. GO FISH Lacks Standing for Both Substantive and Procedural Reasons. The GO FISH Appellants lack of standing has been affirmatively found by the District Court. The Magistrate denied GO FISHs motion to intervene for lack of standing, [Rec. Doc. 7480; 14335], and the District Court affirmed. [Rec. Doc.

37

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 50

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

7747; 15456].62 See also Silverman v. Motorola Solutions, Inc., ___ F.Appx ___, 2013 WL 4082893, at *1 (7th Cir. 8/14/13) (a class action objector must have an interest in the outcome). GO FISH implicitly concedes that the organization has no standing.63 Two weeks after the District Court affirmed the Magistrates Order, GO FISH attempted to cure its standing defect by filing a Notice of Joinder into the organizations objection. [Rec. Doc. 7867; 15638.] These two new individuals, Thien Nguyen and Donald Dardar: (1) failed to make the requisite showing of class membership; and (2) failed to properly file a timely objection in the first instance.64 The GO FISH Appellants standing also suffers from a second fatal flaw. GO FISH does not challenge the settlement recovery under the Seafood Program. Instead, it appeals prematurely to contest the manner in which the second round distribution of benefits under the Seafood program might be conducted. But that determination necessarily awaits completion of the first round of distribution and

62 63

See also Final Approval Order, at 77 [R.E. 1.077; Rec. Doc. 8138; 19922]. See, e.g., GO FISH Appellants Brief, at 46 ([Thien Nguyen] may be the only

[Seafood Class Member] before this Court who has not released his claims individually). 64 Mr. Nguyens notice of joinder in GO FISHs objection was filed on November 7, 2012, [Rec. Doc. 7867; 15638], two months after the September 7, 2012 deadline to file objections, [Rec. Doc. 7225; 11963]. Because the deadline had passed, Mr. Nguyen should have moved for leave. Failure to do so nullified his purported objection and joinder ab initio. U.S. ex rel. Willard v. Humana Health Plan of Tex., Inc., 336 F.3d 375, 387 (5th Cir. 2003) (A party who neglects to ask the district court for leave to amend cannot expect to receive such a dispensation from the court of appeals). Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 15(a) does not apply because leave was never sought for the joinder. U.S. ex rel. Mathews v. HealthSouth Corp., 332 F.3d 293, 296 (5th Cir. 2003) (failing to request leave from the court when leave is required makes a pleading more than technically deficient. The failure to obtain leave results in an amended complaint having no legal effect).

38

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 51

Date Filed: 09/03/2013

an order from the District Court. Neither has occurred and, accordingly, there is no order of the District Court from which GO FISH seeks relief. Even were this Court to determine that GO FISH does have standing, its current appeal should be dismissed as premature. (And even if it were considered now, it fails on the facts already established.) In the District Court, GO FISH conceded that 2.3 billion dollars . . . should be enough to provide all fishermen both duration and parity65 and the alleged problems can be solved within the confines of the Settlements terms by determining a fair Round Two distribution from the Seafood Fund.66 Therefore, because the Settlement was amended to allow the Court appointed neutral to change the allocation formulas to attain fairness on the second distribution of SCP funds,67 GO FISH did not object to the Settlement Agreement; rather, it raised concerns that the Court-Appointed Neutral might make a Round Two allocation different from what some but not other GO FISH members might want or desire. Indeed, GO FISH has acknowledged the non-ripeness of its appeal to this Court: GO FISH believes that, at least with respect to the SCP claimants, the implementation of the Settlement is sufficiently uncertain that review may be

65 66

Go Fish Objection, No. 10-7777, at 3 [Rec. Doc. No. 226; 10715]. Id. at 2-3. 67 Id. at 3.

39

Case: 13-30095

Document: 00512361333

Page: 52

Date Filed: 09/03/2013