Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Samsung and IDP Model

Uploaded by

Ankush GuptaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Samsung and IDP Model

Uploaded by

Ankush GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241 257

Dynamic capabilities, entrepreneurial rent-seeking and the investment development path: The case of Samsung

Jaeho Lee , Jim Slater 1

Birmingham Business School, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom Received 1 July 2006; received in revised form 1 April 2007; accepted 1 May 2007 Available online 24 July 2007

Abstract As noted by Narula and Dunning [Narula, R., Dunning. J.H., 2000. Industrial Development, Globalization and Multinational Enterprise: New Realities for Developing Countries. Oxford Development Studies, 28, 141167.], it has been observed that some of the more advanced developing countries, those rapidly catching-up, outpaced the postulated Investment Development Path (IDP), in which the strategic asset-seeking type of outward foreign direct investment is supposed to occur in later stages, i.e., when countries reach the higher developed levels of economic progress. Firms who led the outpacing in those countries did so through their entrepreneurial commitment to upgrade technological capabilities to maintain and augment their O-advantages rather than because of the overall economic development of their home country. Samsung Electronics' recent success in the semiconductor industry allows us to identify and analyse the factors whereby it not only utilised status-quo resources but also developed dynamic capabilities as it rose to the top. Aggressive and risk-taking investment behaviour in search of entrepreneurial rent and the effective policy of managing technology development contributed to the extraordinary achievement of Samsung Electronics. The company's remarkable transformation over the last decade or so can shed light on how a firm's dynamic capabilities, the ability to improve its O-advantages by reconfiguration, transformation and learning, contribute to its home country's idiosyncratic development path. 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Resource-based view (RBV); Investment development path (IDP); Dynamic capability; Technological capability; Entrepreneurship; Third-world multinationals; Samsung electronics; Semiconductor industry

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44 121 414 7562; fax: +44 121 414 3553. E-mail addresses: j.lee.3@bham.ac.uk (J. Lee), j.r.slater@bham.ac.uk (J. Slater). 1 Tel.: +44 121 414 6703; fax: +44 121 414 3553. 1075-4253/$ - see front matter 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2007.05.003

242

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

1. Introduction Since the early 1980s, the world economy has experienced rapid globalisation. Globalisation has changed the pattern of trade, foreign direct investment (FDI) in world economic activity. However, globalisation has not affected all countries and regions to the same degree. Narula and Dunning (2000) contend that globalisation has resulted in both convergence and divergence: whilst it has resulted in increasing convergence among developed countries and between developed countries and the more advanced developing countries, it has also led to a widening gap between catching up countries (e.g. newly industrialised countries) and falling behind (less developed) countries. Mathews (2006) states that those firms from Far-East countries able to take advantage of the new opportunities arising from globalisation have achieved remarkable success and have even risen to challenge incumbent multinational enterprises (MNEs), leaving behind the firms which did not adapt themselves to the new environment. Globalisation has brought about changes in the Investment Development Path (IDP) paradigm, in which a country's FDI position is systematically associated with its economic development. As is well-known among International Business scholars, The IDP paradigm postulates that countries have a tendency to go through five stages of development and that these stages can be categorised according to the pattern of inward and outward investment. The pattern will rest on three factors in the eclectic paradigm: ownership-specific (O) advantages of the local firms; location-specific (L) advantages of the country; the degree to which local and foreign firms choose to employ their O specific advantages coupled with L specific advantages by the way of internalising the crossborder market (i.e., their (I) advantages) (Dunning and Narula, 1998). However, the rapid economic development of the Newly Industrialised Economies (NIEs) has disturbed the original IDP concept. MNEs from the Far-East have accelerated their internationalization, leading to an increase of outward FDI from those countries on a scale earlier than the IDP would suggest. Outward FDI from developing countries increased from $60 billion in 1980 to $148 billion in 1990 to $871 billion in 2000 and, in 2005, it surpassed $ 1.25 trillion (UNCTAD, 2006). Outward FDI from Asia Pacific firms comprises more than two thirds of the 2005 total. Furthermore, out of the top 40 transnational companies from developing countries identified by UNCTAD, 30 corporations are based in Asia-Pacific and 8 of the top 10 are all from Asia-Pacific.2 Perhaps more revealing, only 3 of the 30 Asian firms compared with more than half of the non-Asian are natural resource-based. How could globalisation enable firms from the NIEs to emerge so rapidly in the world arena? As Narula (1996) has pointed out, the shape and position of the IDP for any particular country is idiosyncratic. However, there appear to be some generalisable implications of globalisation for the IDP. First, Globalisation allowed the new challengers or latecomers to take advantage of new opportunities such as unexplored consumer markets, extended firm linkages, and facilitated resources leverage (Mathews, 2006). Second, in this process, the companies that developed technological capability and creative assets played a major role in the increase of outward FDI from the catching-up countries. Third, the globalisation process, itself, helped the MNEs from developing countries to organize and integrate their global business effectively through new strategic and organizational innovations that are well suited to the new business environment.

2 Mathews (2006) terms these 'Dragon Multinationals' and briefly states short histories of how they emerged, using the examples of Ispat (India), Acer (Taiwan), City Developments Ltd (Singapore), Li & Fung (Hong Kong), Lenovo (China) and Samsung (Korea).

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

243

In this article, Section 2 outlines the main features of the IDP paradigm. In Section 3, we account for how Korea followed its own idiosyncratic IDP path in terms of governmental industrial policy and the big conglomerates' attempts to internationalize. Section 4 presents the Resourcebased View (RBV) of strategy which can be considered as a complementary theory, offering insights into the new trend of increasing outward FDI from developing countries in terms of microlevel firm-specific resources and capabilities. Section 5 outlines our methodology. In Section 6, we expound and analyse the case study of Samsung, narrating the company's rise to become a top-tier semiconductor producer and suggesting a few factors critical in its success as well as its motives for outward FDI. Section 7 concludes with a summary and implications of this research for conventional FDI theories together with some discussion on possible theoretical development in future research. 2. Investment development paradigm (IDP) As briefly mentioned in the Introduction, The IDP paradigm postulates a systematic association between a country's level of economic development and its inward and outward FDI position (Dunning and Narula, 1998; Narula and Dunning, 2000; Dunning, 2000). In this paradigm, a country experiences five stages of economic development, each of which is characterised as having different pattern of inward and outward investment. Outward FDI is expected to take place in later stages when a country has accumulated a certain amount of ownership advantages among firms. In stage 1, a least developed country will have very little inward or outward investment, because it possesses no O or L advantages. Inward investment, if any, is likely to occur with the aim of exploiting natural resources. In stage 2, a country starts to attract inward investment because it has some L advantages such as natural resources or cheap labour, but the outward investment is still low or negligible. In Stage 3, a country begins to experience a decline of the rate of growth of inward FDI, while it witnesses the acceleration of outward investment. At this stage, firms achieve a certain level of technological capability, sufficient to compete with foreign investors in the domestic market, and their foreign investment increases in line with their enhanced competitiveness. Stage 4 is marked by increasing outward investment, to the extent of exceeding or equalling inward investment. The growth rate of outward investment is higher than that of inward investment. At this stage, most domestic firms are expected to compete with foreign firms effectively not only in domestic markets but also in foreign markets. Stage 5 is that of a developed economy: the net FDI position oscillates around zero, that is, inward and outward investment are roughly equal (but both inward and outward investment are likely to be increasing). 3. The Korean IDP, FDI motives and Samsung Globalisation has not uniformly affected the FDI modes and motives across countries. Some less developed countries have been left behind while a handful of more advanced developing countries at Stage 3 converged and caught up with the industrialised countries at Stages 4 and 5. The widely accepted wisdom is that, when inward FDI is combined with the implementation of industrial policy aiming at growing created assets such as education and technological capacity, it can improve the level of competitiveness of national companies and speed up the IDP by raising outward FDI (Hoesel, 1999). In the Korean case, there is an observed variation in this IDP pattern. In Korean development, which has some similarities to that of Japan, the large domestic conglomerates served as the main

244

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

drivers of growth, with relatively low inward FDI from foreign MNEs. As reported by Narula and Dunning (2000), industrial upgrading and cluster development took place in Korea without significant involvement of MNEs from advanced countries. The Government protected domestic consumer markets from foreign MNEs until the indigenous conglomerates were strong enough to take pre-emptive initiatives. Korea attracted less inward FDI from developed countries for natural resource-seeking and efficiency-seeking than many LDCs did. The focus of industrial policy was in rapidly developing created assets and in building up industrial strength. Korean MNEs did not acquire their technology capabilities via knowledge spill-over transferred from MNEs from industrialised countries at Stages 1 and 2. In a sense, Korea did not experience Stages 1 and 2, but, rather, suddenly appeared in Stage 3, ready to go overseas by having accumulated their own technological capabilities. Further, the determination to internationalize by the big conglomerates, such as Samsung, Hyundai and LG, so as to tap into the most advanced technology, led Korean outward FDI to increase significantly. It can be argued that this accelerated internationalization of the big conglomerates would not have been possible if they had not acquired pre-technology capabilities accumulated through the preferential industrial policies by the government (Dunning, 2006). The different stages of the IDP are associated with different relative importance of the four motives for FDI: resource-seeking; market-seeking; efficiency-seeking; and strategic assetseeking (Narula and Dunning, 2000). Asset-augmenting FDI, such as strategic asset-seeking, is unlikely to take place in Stages 1 and 2. Such investment is mainly undertaken in Stages 4 and 5 countries and, to a lesser degree, in Stage 3. There are recent examples of some developing countries in Stage 3 experiencing this type of strategic asset-seeking inward FDI (such as the case of Bangalore in India for software design). There are also examples of firms from countries in the same stage asset-seeking via outward FDI (e.g. Chinese subsidiary companies in California).3 However, while there has been an increase in this type of FDI from/to some developing countries during the last decade, the phenomenon has been viewed as exceptional. Generally speaking, the first three types of FDI will predominate in Stage 1, 2 and 3 countries, the latter type of FDI will occur in Stage 4 and 5 countries. Some advanced developing countries, including Korea, have passed Stage 3 and entered Stage 4. Samsung Electronics one of the most important conglomerates in Korea's industrial upgrading has been taking a major role in enabling Korea to outpace its IDP position, developing its technological capability through aggressive strategic asset-seeking behaviour in the FDI process. 4. IDP, Resource-based View (RBV) and the development of dynamic capabilities in emerging economies The IDP paradigm traditionally attempts to account for cross-border FDI at the country level in terms of macroeconomic change in economic systems. This economic approach provides an explanation of investment patterns among countries using macro-economic variables (Dunning, 1993). Even though it embraces firm-specific micro-factors in the O advantage, which can be regarded as an alternative collective label for resources and capabilities, its main focus is in national economic development. However, recently, it has been observed that, as the globalisation process proceeds and the operations of MNEs grow, many firms cross borders, less in relation to

3 Child and Rodrigues (2005) document that companies in developing countries implement asset-augmenting type of outward FDI to address their competitive advantage by closing the gap between them and leading companies through gaining assets and resources which would not be otherwise available.

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

245

the economic status of their home country, but more according to their own competitive advantages, which are embedded in their technological capabilities and accumulated knowledgebased assets. Accordingly, while IDP is still a valid paradigm that shows an empirically confirmed pattern of inward and outward FDI, we argue that there are particular dynamics of firm-specific factors that may lead to yet further deviation from the conventional pattern. In this context, the Resource-based View (RBV) can be viewed as an effective theory to provide insights into recent trends in FDI. RBV aims to account for outward FDI in terms of the idiosyncratic resources and capabilities a firm possesses (Trevino and Grosse, 2002). The RBV would advocate a detailed analysis of the firm-specific resources and capabilities that underpin the ownership advantage necessary for competitive advantage. The RBV views organizations as bundles of resources combined with organizational capabilities or core competencies and states that these resources and capabilities are the primary determinants of strategy and performance (Barney, 1991; Grant, 2003). Barney (1991) argued that successful strategy rests on sustaining competitive advantage derived from resources and capabilities, the bundles of all assets, management skills, organizational processes and routines etc. Grant (2003) approaches the RBV similarly, classifying resources into the tangible (financial and physical resources), the intangible (technological resources, reputation), and human: capabilities reflect the effective deployment of these resources. The RBV shifts the perspective on strategy formulation from the external environment towards the internal environment of the firm, in the sense of identifying the latter in terms of the bundles of resources and capabilities it possesses (or can access), from which sustainable competitive advantage may be constructed. Resources owned by a firm direct its diversification process and determine its organizational form for diversification (Wernerfelt, 1984). Outward FDI is a mode of diversification that takes place at international level and is an effective vehicle to absorb and generate new resources and capabilities, leading to improved performance. Empirical research has linked resources and capabilities to international diversification. Example of resources and capabilities in this context for successful outward FDI include administrative heritage (Collis, 1991), organizational practices (Zaheer and Mosakowski, 1997), bargaining power (Moon and Lado, 2000), experience with product diversification (Hitt et al., 1997), experience of innovation and R&D (Bettis and Hitt, 1995), international experience of top management teams (Sambharya, 1996) etc. Whilst the IDP is a stage model which links the different patterns of FDI in terms of their macro-economic development, the RBV does not offer any analogous stages that a firm may experience in the process of international expansion (Peng, 2001). Rather, RBV posits that a firm with appropriate resources and capabilities may sustain competitive advantage through FDI, but, though achieving this may be path dependent, there is no prescribed path. In this respect, RBV challenges the stage models and a lot of theoretical and empirical studies demonstrate the presence of international entrepreneurship from emerging economies. There is recent evidence that size is becoming less important in the process of globalisation: many small and mediumsized enterprises (SMEs) are able to internationalise more rapidly predicted (Hoskisson et al., 2000; Lu and Beamish, 2001) with superior tacit knowledge about global opportunities (Peng et al., 2000), or superior capability to control such knowledge in an unequalled manner (Peng and York, 2001). Another approach, complementing and enhancing the RBV, enables us to analyze successful outward FDI from emerging economies in terms of dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial rent-seeking behavior. Teece et al. (1997) define dynamic capabilities of a firm as the subset of the competencies/capabilities which allow the firm to create new products and processes, and respond to changing market circumstances. They state that competition among firms (on the basis of

246

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

product design, product quality, process efficiency and other attributes) can be explained, at one level, in terms of exploiting arbitrary gains that remained previously unexplored in the market', and that, from the point of view of the dynamic capabilities approach, firms are constantly seeking to create new combinations of the product, process, organisation and technology, and rivals are continuously attempting to improve their competencies or to imitate the competencies of their most qualified competitors'. Such processes entail the process of creative destruction in Schumpeter's (1934) terms. Teece et al. (1997) also state that differences in firms' capabilities to improve their distinctive competencies or to develop new distinctive competencies play a critical role in shaping long-term competitive outcomes'. It has been observed that some MNEs from emerging economies went overseas with an array of resources and capabilities that might be viewed as insufficient from the RBV. However, through their dynamic capabilities they transformed their management practices and organizational routines in an innovative way, redesigning and reconfiguring their resources and capabilities. The important implication of dynamic capabilities for management research is that resources and capabilities do not constitute a, static pool but, may be creatively reorganized, improved and upgraded, taking an organization on to another level of competitiveness. Dynamic capabilities have another important theoretical implication, reinforcing the recognition that firm-specific methods of coordinating resources may result in the heterogeneous behavior of firms in the same industry. The notion of path dependency explicitly allows for firms to have developed different capabilities through the unique histories and strategic trajectories. Tokuda (2004) argues that the RBV views the valuable resources of a firm as given and that, in this paradigm, the planning and investment to utilize such resources are exogenous. He also argues that the RBV is more likely to overestimate the potential profitability of firms that have unique resources, because it ignores the cost of acquisition and accumulation of such resources and the different ways of utilizing them. The standard RBV itself cannot answer why firms invest in valuable/unique resources rather than in other types. Barney (2001) states that a firm's competitive advantage over others may derive, in part, from its expectation, different from others, about future returns from its resources. Entrepreneurial expectation, heterogeneous across firms, and the insight and perspective which influence the organization and coordination of resources inside the firm can be significantly important resources in themselves and may contribute to super-normal returns from an investment (Tokuda, 2004). Gick (2002) affirms that entrepreneurial innovation is a source of entrepreneurial rent, which can be viewed as the pay-off that the entrepreneur receives as a result of his innovative way of combining resources and capabilities. Casson (2005) also points out that an entrepreneur's unique way of coordinating resources, especially human resources, is reflected in rent-seeking behavior. The capabilities of scientists and mangers are not as important in themselves as entrepreneurs' abilities to coordinate, because it is the entrepreneurs who ultimately control organizations. Therefore, we find it necessary to add further dimensions to the RBV framework. The conventional RBV considers a firm as a relatively static pool of resources and capabilities. However, if firms' competences to identify and utilize resources are heterogeneous, where do these capabilities derive from? We observe that some outward FDIs from emerging economies were implemented specifically to develop technological capability and we need to consider to what extent, and how, firms perceive the resources they possess idiosyncratically and develop their capabilities differently. We are focusing on, through the analysis of the Samsung case in the next sections, a sort of second order organizational capability which is dynamic: the ability to recognize core capabilities and change them.

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

247

5. Methodology Samsung is the focus of this article. We believe that the case study methodology is best suited to investigating the uniqueness of entrepreneurially-driven strategy. A case study can be employed when it raises the question of what specially can be learned about even the single case (Stake, 2005) and, conventionally used, the case methodology can shed light on understanding the development process that Samsung has experienced in terms of its pertinence to RBV theories and the IDP paradigm. While it is likely that quantitative methodology would yield ambiguous empirical results about Samsung's emergence and performance, it was expected that the case study would provide a more in-depth and clear analysis of the factors which led to success in terms of RBV/ Dynamic Capabilities accounts of strategy and international business. Samsung started with few resources to develop semiconductor products, but aggressively and dynamically attempted to access and tap into the relating technologies in global markets. Through a series of events during the last decades in the process of development of new technology, Samsung rose to become a first-rate company in the semiconductor and consumer electronics industries, proving itself as a flagship of the Korean economy. The analysis of the Samsung case within the enhanced RBV framework will provide us not only with insights into the successful strategy of this company, but also into the apparent discontinuity with the IDP. We aim to single out the factors which contributed to Samsung's success and analyze how they are relevant to understanding the RBV theories that challenge the IDP paradigm. Further, we aim to identify and examine the entrepreneurial aspects which have driven the dynamic capabilities leading to the unique organizational capabilities that made it possible to develop and sustain the most advanced cutting-edge semiconductor technology. In order to do this, we mainly use secondary data, although supplemented by primary data from Samsung Electronics employees. This case study owes its writing to a number of previous case studies written by major business schools, newspapers, magazines and annual reports of Samsung. It needs to be backed up by more interviews and probably ethnographic studies in the future, but we would say that the abundant secondary data were sufficient for us to understand what factors have had an impact on the development of Samsung's technological capabilities and their implications for the theories and paradigm of international business and strategy. 6. Samsung Electronics, dynamic capability development and implications for the RBV 6.1. Overview of Samsung Electronics In 2005, the Samsung Group, of which Samsung Electronics is a subsidiary, was the largest conglomerate (chaebol) in South Korea. The total net sales of the Samsung Group reached $140.9 billion in 2005, and net income $9.4 billion. In the same year, the Samsung Group had total assets worth $233.8 billion and its market capitalisation amounted to $80.8 billion (see Table 1 in Appendix). Having its headquarters in Seoul, the Samsung Group has 337 offices and facilities in 58 countries globally. It employs approximately 229,000 people worldwide. It has 14 listed companies within the group and the three core business sectors are electronics, finance, and trade and services. Samsung Electronics is the flagship company. It was established in 1969 as a black-and-white TV set production company and grew to be one of the largest electronics companies in the world. At the end of 2004, the company had $78.5 billion in net sales, $66 billion in assets, and 113,000 employees worldwide. According to Interbrand, the company's brand value increased from

248

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

$5.2 billion (ranked 43rd in the world survey) in 2000, to $12.6 billion (ranked 21st) in 2004, and to $15.0 billion (ranked 20th) in 2005. Over the 5 years, Samsung Electronics has posted the biggest gain in value out of the other global 100 brands, with a 188 percent surge. In 2005, the brand value of Samsung Electronics exceeded, for the first time, that of Sony, which remained at 28th. Samsung Electronics consists of five business divisions, including the Semiconductor Business that is the core business within the company. Other divisions include the Digital Media Business, which produce TVs, AV equipment, and computers; the Telecommunication Business, which manufactures mobile phones and network equipment; the LCD Business, which makes LCD panels for notebook computers, desktop monitors, and HDTV; and the Digital Appliances Business, which produces refrigerators, air conditioners and washing machines. 6.2. Samsung Electronics' emergence as a top-tier global semiconductor and consumer electronics company Samsung Electronics' interests in semiconductors started in the early 1970s, with the initiative of Byung-chul Lee (who was the founder of Samsung Group) and his son, Kun-hee Lee (who later rose to the same position after his father died). They saw the potential of semiconductor industry in expectation of its high growth and profitability, and decided to move into this industry. At that time, Samsung Electronics was a mere producer of low-end consumer electronics, which imported and assembled semiconductors and other items to export the consumer electronics products. During the 1980s, Samsung Electronics chose to enter DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memories) production, the high-growth memory segment. To design and produce its first 64 K DRAMs, Samsung Electronics searched around the globe for a company willing to license its DRAM technology. Leading foreign producers declined Samsung Electronics' request to license DRAM technology, but the company approached a number of financially-distressed small semiconductor companies in the US and ultimately purchased chip designs and process technology from Micron (Kim, 1997). By the mid 1980s, Samsung Electronics was building its first large manufacturing facility. The company accomplished the construction for a new production facility in just six months. With the aim of developing its first frontier technology, Samsung Electronics set up two task forces in America and Korea and employed KoreanAmerican Ph.D.s in the field of electronic engineering. The two taskforces interacted actively and the team in Korea succeeded in developing 64 K DRAM. The two groups cooperated but competed at the same time to come up with their own solution, and they took turns in developing next generation DRAM technology (Kim, 1997). Samsung gained number one market share position in the DRAM industry in 1992 and have maintained their leadership position since (Siegel and Chang, 2005). From 1994, the DRAM boom turned to decline and in 1995 Samsung Electronics' total return on investment was only 60% of 1994 levels. The DRAM market was saturated. Even though Samsung Electronics suffered, it kept investing in facilities and R&D, establishing joint ventures in many countries. Through this aggressive and bold investment in developing the next-generation DRAM chips, Samsung Electronics would crack the 1 G DRAM by 1996 (Haour and Cho, 2003). In 1997, the Asian Financial Crisis began to aggravate the DRAM situation. The stock price of Samsung Electronics recorded its lowest since 1994. Over this period, the Samsung Group, including Samsung Electronics, had to go through substantial corporate restructuring. However, the company benefited from the weakened Korean currency and a strong rebound in market demand and price for DRAM in the late 1990s. Samsung Electronics' commitment to DRAM development despite falling demand paid off finally, outwitting rival companies. However, the

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

249

company learned a lesson and began to devise a new strategy to reduce its dependence on DRAM by diversifying into other areas. Samsung Electronics also made a major move into non-memory chips. Entering the 2000s, Samsung Electronic aimed at a digital convergence strategy where it diversified product mix to provide full-range products from memory chips to high-end state-ofthe-art consumer products. It would aim for convergence through continuous innovation in product lines (Kumar, 2004) (see Table 2 in Appendix for a detailed history of Samsung Electronics). 6.3. Samsung Electronics' technological capability development and its implications for RBV and IDP 6.3.1. Motives for FDI: strategic asset-seeking, efficiency-seeking and market-seeking Samsung Electronics' FDI in the US for the development of DRAM technology was primarily strategic asset-seeking and market-seeking. Even after Samsung Electronics was able to stand on its own two feet for developing DRAM technology, the company invested heavily in the establishment of joint ventures and production plants in various countries. These investments had two motives. First, by founding joint ventures and sharing research centres, Samsung Electronics was not only trying not to lag behind, but also leap to the forefront of DRAM technology4. This FDI was not only in developed countries: Samsung Electronics established a subsidiary in Bombay, India, to employ local highly-skilled software engineers. This case is a good example to show how Samsung Electronics attempted to maximise its I advantage using the O advantage amassed over the period combined with a newly found L advantage all with the overriding motive of exploiting a strategic asset crucial to its technology development. Given Korea's IDP position (between Stage 3 and Stage 4) Samsung's venture into this type of FDI is remarkable. The most significant factor influencing this investment behaviour is in the competencies of Samsung Electronics rather than from the overall economic position of Korea. Firm-specific O advantages (tangible and intangible resources and the capability to deploy them) were embedded and developed dynamically. Second, it is noted that this strategic asset-seeking investment has been intertwined with market-seeking. Samsung Electronics has carefully noted the potential of consumer markets and attempted to devise appropriate strategies to tap into them and catch up. For example, a design centre was founded in London, UK for a variety of motives: to learn design skills from London designers, who are considered to be in the van of world design and to research consumer taste about mobile phone design, which can be very different from that in Korea. This case also shows how Samsung utilised its O-advantage, coupled with the UK's locational attraction, to select the internalisation mode to maximise its I-advantage. 6.3.2. Entrepreneurial rent-seeking aggressive and entrepreneurial investment behavior Samsung Electronics did not start with adequate resources to enter the DRAM industry. Rather, Samsung Electronics possessed the dynamic capabilities to use and leverage a limited range of resources and competencies to improve their technological capabilities through an ongoing development process. Samsung Electronics' advance to become a top-tier innovative firm

4 The collaborative forms of gaining entry undertaken by Samsung, such as partnerships and joint ventures, are consistent with the phenomena described by Wells (1998) about multinationals from the Third World. Mathews (2006) points out that multinationals from the Third world tend to internationalise through the collaborative entry to reduce the risks and to utilise web-like global interlinkages. This compares with incumbent MNEs from the developed world who prefer the internalisation mode, through establishing subsidiaries.

250

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

does not conform to conventional resource-based theory. There is no correlation between exante resources and ex-post performance in Samsung Electronics' case. However, while the conventional RBV views the firm as a static bundle of resources and capabilities and assumes homogenous expectations about costs of strategic factor markets and profitability of future operation, revision of RBV from a dynamic viewpoint offers a richer perspective. Subjective, heterogeneous expectations, characteristic of entrepreneurial behavior, of firms regarding costs and profitability in the current and future business environments may generate different actions for the dynamic development of resources and capabilities. Samsung Electronics' continuous aggressive and bold investment in DRAM technology throughout the 1980s and 1990s despite the severity of the industry cycle shows how differently Samsung Electronics' leadership perceived the industry potential. While competitors in Japan and the US started to reduce their investments in the face of adverse conditions in the mid-1990s, Samsung Electronics continued with huge investments in the technology, which finally paid off when the industry rebounded in 1999. This continuous commitment to DRAM investment is characteristic of entrepreneurial behavior: to seek for rents that can be won in a high risk venture. In this process, as Casson (2005) pointed out, the entrepreneur's (in Samsung Electronics' case, top manager's) vision and strategic cohesion enabled crucial decisions such as selecting the right people with the right capabilities and allocating the right resources to the right tasks and positions. In short, Samsung Electronics' extraordinary technological capability development in the DRAM industry suggests that dynamic entrepreneurial capabilities should be interwoven more into the theoretical mainstream of strategy. 6.3.3. Development of technology capability: assimilation, imitation and competence Samsung Electronics' technological learning in the process of DRAM chip development at early stage shows that the company was totally engrossed in generating the new technology by using their dynamic capabilities. All the resources and capabilities they could access at the time that they entered semiconductor production resulted from their experience of assembling the semiconductors imported from developed countries. In a static capabilities sense, Samsung Electronics did not have the resources to design memory chips or to construct the facility to produce them. However, the company improved and developed its technological capabilities, including the absorptive capacity to make effective use of foreign technological know-how, utilizing its dynamic capabilities in the process to create new combinations of product, process, organization and technology. Through persistence and determination, it gained access to foreign companies and license to imitate their memory chip technologies, but this does not explain the extraordinary absorption and innovation which followed. Samsung Electronics' initial attempts to license 64 K DRAM technology were turned down by major semiconductor companies in the US and Japan. The company organized a task force team in 1982 to devise an entry strategy for DRAM technology, but required a major technology leap from its current form of operations. Samsung Electronics identified financially troubled small firms to buy DRAM technology and licensed 64 K DRAM design from Micron Technologies in Idaho. Kim (1997) points out that the technology license from Micron provided Samsung Electronics with a platform to reduce the time in learning explicit and tacit knowledge related to 64 K DRAM design and production. Samsung Electronics bought a design for a high-speed process instrument from Zytrex of California, enabling them to acquire explicit knowledge. They dispatched their engineers to these companies so that they could be trained to assimilate the license technologies (Kim, 1997). They arranged the process of transferred technology assimilation gradually from the

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

251

simplest to the more complicated: from the assembly process to process development, then to facility development and inspection (Kim, 1997). Samsung Electronics' previous experience of assembling chips enabled Samsung engineers to gain initial familiarity with the new products and processes imported from Micron and Zytrex, this time elevating the capability to assimilate and adapt to DRAM technology. This initial acquisition of DRAM technology from the US companies can be described as the process of making the most of the company's current capabilities and combining as many and as varied types of capability as possible to imitate and improve their overall technological capabilities. Samsung Electronics' dynamic capabilities were utilized to advance from imitation to innovation. The strategic issue facing an innovating firm in the process of developing dynamic capabilities is related to how it decides upon and develops difficult-to-imitate processes and paths most likely to support valued products and services' in the long-term (Teece et al., 1997). As argued by Dierickx and Cool (1989), commitment to investment is central to this issue, with the firm's competencies being influenced by the actual paths followed. After successfully completing the development of 256 K DRAM, Samsung Electronics surpassed the initial stage of assimilating DRAM technology from foreign companies and followed its own trajectory or path of competence development thereafter. Though faced by significant uncertainty about the future state of the DRAM industry in the mid-1990s, Samsung Electronics decided to take its own path to develop next-stage DRAM chips, resulting in global leadership. Mathews (2003, 2006) points out that successful multinationals from Asian countries effectively controlled the process of economic learning through using linkages (interconnected firm relationship) and leveraging resources. Samsung's persistent endeavor to learn DRAM technology from the US firms and to concentrate firm resources on cracking its own technology is in line with the strategic decisions taken by those other challenging firms from Asia. 6.3.4. Crisis management creation and human resources management We have referred to Samsung's extraordinary performance deriving from its unique dynamic capabilities. The dynamic capabilities are manifest in the managerial means whereby it developed technological capability so rapidly. The organization's breakthrough in its own development of initial stage DRAM chip technology came with a specifically designed human resources management mode: two task forces (in Korea and the US) were set to work in crisis management mode, a deliberate means of creating tension to accelerate progress. Samsung Electronics searched for information on the DRAM technology and market in early 1980s in the US and organized a US R&D task force for DRAM chip development that was composed of five Korean American with Ph.D.s in electronic engineering who had semiconductor design experience at major US semiconductor companies. Samsung Electronics also set up another task force in Korea with two KoreanAmerican scientists who had an experience of DRAM development. Active interaction and communication between these two taskforces through training, joint research and consulting transferred explicit and tacit knowledge from the American outpost to Korea effectively, making Samsung Electronics' engineers prepared to assimilate DRAM technology (Kim, 1997). In order to intensify its effort, Samsung Electronics intentionally generated the crisis management mode by insisting that the team in Korea develop a working development system within certain deadline. After 6 months' time, the team in Korea assimilated the core technologies. For the development of the next-stage, both task forces were assigned to develop their own process. The projects were in a sense competitive because they both were to work on the same project. However, it was in another sense collaborative because they were to exchange information, personnel and research results' (Kim, 1997). As in the case of 64 K DRAM, a

252

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

deadline was also given to both teams, putting a great deal of pressure on them in crisis management mode again. Samsung Electronics cracked the next-stage in DRAM technology by using competition and collaboration between the two task forces. The American task force took a leading role in the development process and the Korean task force absorbed the necessary core technology to master the working process. Samsung Electronics introduced an effective HR strategy to place two task forces under pressure to compete and collaborate to elevate its technology level within a target, but relatively short, time. 5 6.3.5. R&D support and technology capabilities Samsung Electronics' main R&D facilities are located at a single site, Kiheung, just south of Seoul, Korea. The foremost and core semiconductor research is conducted at this site and all the information and research results from overseas are concentrated to this site. When a project reaches a deadlock, all related researchers gather together to sort out the problems until they come up with a solution. As in the case of the initial stage of DRAM chip development, the engineers and scientists are generally given a certain time of period such as a week, 2 weeks or a month to complete a project. This perpetually crisis-generating approach results in most projects being finalized within their deadlines. The projects are extremely well resourced. At Samsung's primary campus, the R&D engineers and scientists stay together in the same company-provided luxury housing. They share meals and their worksites are in proximity so that design and process engineering problems can be quickly solved together. This site was designed to provide all the necessary R&D support enabling researchers to concentrate on the work itself. Samsung Electronics have invested more than 20% of its net income in R&D over the years, which is the highest R&D ratio among the major semiconductor competitors. This company policy, specifically geared to expand and support R&D, is one of the resources and capabilities that enabled Samsung Electronics to reach the top-tier of technological leadership in the semiconductor industry. 6.3.6. Financial resources transferred within the group When Samsung Electronics successfully developed its own 64 K DRAM and 256 K DRAM, Japanese semiconductor moved quickly to dump their 64 K and 256 K DRAMs at the Korean producers' cost. This strategy worked early on, placing enormous financial strains on their American competitors. However, unlike the single business semiconductor producers in the US, Samsung Electronics could overcome this financial difficulty, mainly supported by the cash-cow subsidiaries within the diversified Samsung Group. This financial assistance from other affiliates within the Group enabled Samsung Electronics to keep itself afloat during the financial crisis until Samsung Electronics emerged as dominant suppliers of the 64 K DRAM and 256 K DRAM in the US market. Furthermore, the continuous commitment to DRAM investment in times of DRAM market recession and the Asian Financial crisis would have been impossible without the financial support from the Group affiliates. Samsung Electronics' ready access to funds from cash-cow companies within the Group played one of the major roles in providing cushions to Samsung Electronics when it was faced by financial constraints and the need to expand

In an interview article with Mr. Jong-Yong Yun, CEO of Samsung Electronics, in Fortune, Lewis (2005) caught the word perpetual crisis machine to account for the management and operation mode of Samsung. Mr. Yun emphasized that, despite the success over the last decade, Samsung cannot afford to relax but needs to be in continuous tension, looking 10 years ahead if not to be caught by competitors.

5

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

253

investment. The ability to generate funds and arrange favorable access to them can be called a unique resource (Dunning, 2006) and underpins at least some of Samsung's sustainable O advantages. 7. Conclusion: Samsung Electronics' technology development and its contribution to IB theories As noted by Narula and Dunning (2000), it has been observed that some of the more advanced developing countries, those rapidly catching-up, outpaced the IDP. That is, they reached the stage of strategic asset-seeking outward investment before the higher level economic development was attained. Dunning (2000) notes the dynamic competitiveness and locational strategy of the firms in those countries, and in particular, the path-dependency of their upgrading of core competencies. Firms that have leapfrogged their technological capabilities to come to the fore over this period have achieved this because of their capability to maintain and augment their O-advantages rather than by the overall economic development stage of their home country, although, of course, the growth of the firms is indebted to spillover from national economic development. While the state of economic development, especially the government's industrial policy, acted a catalyst for enabling firms to accumulate initial pre-globalisation resources and capabilities, firms' pre-emptive initiatives to access resources available in the global market made possible the rapid internationalization and the rise of outbound foreign direct investment. Samsung Electronics' transformation from an ordinary second-rate consumer electronics manufacturer to a top-tier semiconductor producer is noteworthy and can assist in identifying and analyzing the causes of success of prominent firms in the developing countries, especially of the East-Asian conglomerates. We suggest there are a number of implications. First, while the IDP has been considered a paradigm to account for the patterns and trends of inward and outward FDI according to the economic development stage of countries, it needs to incorporate a broader view of the role of MNEs or entrepreneurial SMEs who attempt to elevate their technology capability through their own initiatives. This may indicate that O-advantages of entrepreneurial firms, which endeavour to utilise the specific resources with the motive of strategic-asset seeking, will have a greater role in accelerating cross-border investment in the future. Second, Samsung Electronics' success sheds light on understanding the resources of the firms that are considered crucial to their operation in the RBV. It is not the static pool of resources, but the entrepreneurial dynamic development of capabilities that is central to the success of firms which not only catch up, but also overtake their counterparts from the developed economies. Subjective, heterogeneous expectations about production input costs and potential profits can lead to different outcomes even with the same domains of resources that different firms possess. Samsung Electronics' advancement into a top-tier innovative company was derived from the top management's anticipation of the market potential of semiconductor industry and the ensuing aggressive commitment to the seemingly high-risk investment. The competencies of the company were developed through the process of acquiring and deploying resources in a dynamic way to seek for entrepreneurial rents. We also would like to suggest some theoretical developments to be considered in the future from our research. First, IB theory needs to assimilate the knowledge of how firms develop their O-advantage through developing dynamic capabilities and to recognise that entrepreneurial vitality is the driving force. We think that IDP paradigm, which basically represents the relationship between economic development (technically, GNP level) and net investment position of a country, can be conceptually strengthened by adopting different types of economic variables

254

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

that measure, for example, technological and innovation capacity along with entrepreneurial behaviour, so possibly predicting more dynamically the future development path a country will experience. Second, we suggest that there be more analyses which examine the emergence of multinationals from developing countries in terms of how different dynamic capabilities contingent upon specific conditions impact on technology and management practice. One plausible area of research might seek for commonalities or otherwise in the circumstances in which firms deploy their dynamic capabilities to reorganise resources and which kind of technology learning modes are adopted. For example, Zahra et al. (2006) hypothesize that learning modes such as improvisation, trial-and-error learning, experimentation and imitation are influenced by dynamic capabilities under different conditions such as firm age. How does learning mode correlate with firm age and how do dynamic capabilities evolve? Multinationals from developing countries are relatively young compared to those from developed countries, so that a systematic relationship is likely to have significant implications for the strategies of these companies. Third, there needs to be more examination of the relationship between dynamic capabilities and more basic (threshold or substantive (Winter, 2003)) resources and capabilities. Would it have been possible for Samsung to rise to its current position without experience of assembling semiconductor parts as an OEM exporter before entering full scale D-RAM development and production? The technological learning accumulated through this experience was itself a path-acquired resource. Samsung's dynamic capabilities could be regarded as a fertilizer for the next growth stage. An attempt to coordinate organization resources in a more creative and innovative way may not work unless based upon adequate substantive capabilities. The interaction and co-evolution of dynamic and substantive capabilities could be a beneficial area for further research. Recently, there has been debate concerning how new multinationals' strategic asset-seeking type of FDI can be fitted into the conventional eclectic OLI paradigm. Mathews (2006) suggests this type of internationalization is driven by new three factors, which he terms the Linkage, Leverage and Learning (LLL) paradigm. His main point is that new multinationals, as both latecomers and newcomers, are able to gain advantage through access to foreign technology because of their abilities to network, overcome entry barriers and learn effectively. Future research may gain fresh insights from this perspective aligned with the traditional OLI paradigm. There are other large companies from East Asia that have become multinational in a relatively short period. Some, like Lenovo and Acer, are in the information technology industries, and there are similarities with Samsung in that entrepreneurial effort has been directed towards technological innovation. Others, such as Haier, have sought competitive advantage through strategic innovation: in quality management and marketing, for example. All seem to have in common strong, entrepreneurial leadership. We have endeavoured in this article to shift the focus on growth and development from managerial processes to the primary dynamic capability of entrepreneurship that drives their design, implementation and change. While this article aimed to analyse the unique path Samsung has taken, our arguments need to be reinforced by other examples in different countries, to identify whether the dynamic capabilities perspective would apply to the success of other companies. The comparative studies which examine why, to what extent, and how differently dynamic capabilities affect the path and the process of organisations will contribute to better understanding of success/failure of the companies in wider perspective. Furthermore, strategy, is of course, far from independent of the external environment, and although we have hinted at macro-environmental factors in the case of Samsung, the extent to which external factors encourage, discourage, shape, direct or divert entrepreneurial behaviour has not been covered in this paper and needs to be explored in future research.

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

255

Appendix A

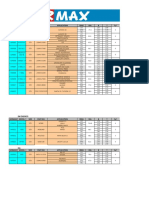

Table A1 Samsung's summarised financial and income statistics 2000 Net sales Total assets Total liabilities Total stockholder's equity Net income Employees 119.5 113.7 84.8 28.9 7.3 174 2001 98.7 124.3 88.8 35.5 4.5 170 2002 116.8 156.1 110.3 45.8 8.9 175 2003 101.7 170.4 113.8 56.5 5.6 198 2004 121.7 209.4 137.2 72.2 11.8 213 2005 140.9 233.8 153.0 80.8 9.4 229

Source: Samsung Group homepage (www.samsung.com). Dollars in billions (except for employees in thousands).

Table A2 History of Samsung Electronics (19692005) Year Events 1969 1970 1972 1977 1983 1986 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Samsung Electronics Manufacturing Co., Ltd., SamsungSanyo Electronics Co., Ltd. Established SamsungNEC Co., Ltd established Started production of black and white TV sets 100% share of Korea semiconductor Co., Ltd acquired Started production of personal computers; 64K DRAM developed 1 M DRAM developed; research labs established in the US and Japan 4 M DRAM developed; Samsung Semiconductor and Telecommunications Co., Ltd. Merged with Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd VLSI R&D Centre completed; company ranked 13th in the world for semiconductor sales 16 M DRAM developed Super-VHS VCRs and Pen-based PCs developed 64 M DRAM developed; technical cooperation with Toshiba of Japan for semiconductors Completed plans for the mass production of 16 M DRAM 256 M DRAM developed; exports exceeded US $10 billion Stared mass production of 64 M DRAMs TFT-LCD mass production started Established a fully integrated production complex in Suzhou, China Investment (40.25%) in shares of AST Research Established a semiconductor plant in Austin, Texas, USA 1 G DRAM developed Singed on as worldwide Olympics partner through year 2000 Began to ship CDMA PCS handsets to Sprint Spectrum Developed 30-inch single glass TFT-LCD Shipped samples of world's first 128M SDRAM SAS (Samsung Austin Semiconductor) started production World's first 256 M DRAM chips produced TFT-LCDs capture No.1 global market share position First DRAM manufacturer to receive Intel validation for its 72 M and 144 M Rambus DRAMs 1 GHz alpha CPU developed 1 GIGA bit flash memory chip developed Corporate Strategy shifted to specialization in Digital Industry Developed world's smallest packages for SRAMs Samsung and Microsoft announced strategic alliances to deliver next-generation mobile phones (continued on next page)

1996 1997

1998

1999

2000

256

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

Table A2 (continued ) Year Events 2001 Launched very-thin 0.7 mm flash memory packages Developed colour motion picture function in mobile phone Developed 576 MB RDRAM 2002 Developed 128 MB DDR graphic memory chip Shipped the industry' first 256 MB SDRAMs made from 300 mm wafers Developed the industry's first DDR-SDRAM 2003 Introduced ITCAM-7: world's first HDD digital camcoder Received Sun Microsystem's supplier of the year Developed 57-inch TFT-LCD panel for HDTVs 2004 Developed 70-nanometer DRAM process technology Samsung Electronics and Qaulcomm, Inc. delivered MDDI display interface solution for wireless 3 G CDMA clamshell phones Developed high-integrated HDTV system-on-chip 2005 Brand value published by Interbrand ranked 20th, exceeding that of Sony (28th) for the first time Developed New Satellite DMB phone Developed world's first 512-Megabit DDR2 with 70 nm Process Technology Source: Press release section in Samsung Group homepage (www.samsung.com).

References

Barney, J.B., 1991. Firm resources and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17, 99120. Barney, J.B., 2001. Is the resource-based views' a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review 26, 4156. Bettis, R.A., Hitt, M.A., 1995. The new competitive landscape. Strategic Management Journal 16, 720. Casson, M., 2005. Entrepreneurship and the theory of the firm. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 58, 327348. Child, J., Rodrigues, S.B., 2005. The internationalization of Chinese firms: a case for theoretical extension? Management and Organization Review 1, 381410. Collis, D., 1991. A resource-based analysis of global competition: the case of the bearings industry. Strategic Management Journal 12, 4968. Dierickx, I., Cool, K., 1989. Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science 35, 15041511. Dunning, J.H., 1993. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Addison Wesley, Wokingham. Dunning, J.H., 2000. The eclectic paradigm as an envelope for economic and business theories of MNE activity. International Business Review 9, 163190. Dunning, J.H., 2006. Comment on dragon multinationals: new players in 21st century globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 23, 139141. Dunning, J.H., Narula, R., 1998. The investment development path revisited: some emerging issues. In: Dunning, J.H., Narula, R. (Eds.), Foreign Direct Investment and Governments. Routledge, London. Grant, R.M., 2003. Contemporary Strategy Analysis. Blackwell, Oxford. Gick, W., 2002. Schumpeter's and Kirzner's entrepreneur reconsidered: corporate entrepreneurship, subjectivism and the need for a theory of the firm. In: Foss, N.J., Klein, P.G. (Eds.), Entrepreneurship and the Firm: Austrian Perspective on Economic Organization. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. Haour, G., Cho, H., 2003. Samsung Electronics Co., LTD(A): radical innovation for the DRAM Business. IMD Case Study. Hitt, M.A., Hoskisson, R.E., Kim, H., 1997. International diversification effects on innovation and firm performance in product diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal 40, 767798. Hoesel, R.V., 1999. New Multinational Enterprises from Korea and Taiwan. Routledge, London. Hoskisson, R.E., Eden, L., Lau, C.M., Wright, M., 2000. Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal 43, 249267. Kim, L., 1997. The dynamics of Samsung's technological learning in semiconductors. California Management Review 39, 86100. Kumar, S., 2004. Samsung Electronics' Turnaround. ICFA Case Study.

J. Lee, J. Slater / Journal of International Management 13 (2007) 241257

257

Lewis, P., 2005. A perpetual crisis machine: Samsung's VIP center is home to a uniquely paranoid culture and that's the way the boss likes it. Fortune 152, 5876. Lu, J., Beamish, P., 2001. The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal 22, 565586. Mathews, J.A., 2003. Competitive dynamics and economic learning: an extended resource-based view. Industrial and Corporate Change 12, 115145. Mathews, J.A., 2006. Dragon multinationals: new players in 21st century globalization. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 23, 527. Moon, C., Lado, A., 2000. MNC-host government bargaining power relationship: a critique and extension within the resource-based view. Journal of Management 26, 85117. Narula, R., 1996. Multinational Investment and Economic Structure. Routledge, London. Narula, R., Dunning, J.H., 2000. Industrial development, globalization and multinational enterprise: new realities for developing countries. Oxford Development Studies 28, 141167. Peng, M.W., 2001. The resource-based view and international business. Journal of Management 27, 803829. Peng, M.W., York, A., 2001. Behind intermediary performance in export trade: transactions, agents, and resources. Journal of International Business Studies 32, 327346. Peng, M.W., Hill, C.W.L., Wang, D.Y.L., 2000. Schumpeterian dynamics versus Williamsonian considerations: a test of export intermediary performance. Journal of Management Studies 37, 167184. Sambharya, R.B., 1996. Foreign experiences of top management teams and international diversification strategies of US multinational corporations. Strategic Management Journal 17, 739746. Samsung Group Website (www.samsung.com). Schumpeter, J.A., 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Siegel, J.I., Chang, J.J., 2005. Samsung Electronics. Harvard Business School Case Study. Stake, R.E., 2005. Qualitative case studies. In: Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications, London. Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A., 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. In: Foss, N.J. (Ed.), Resources, Firms, and Strategies. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Tokuda, A., 2004. Amending the resource-based view of strategic management from an entrepreneurial perspective. Economics and Management Discussion Paper 18. The University of Reading Business School. Trevino, L.J., Grosse, R., 2002. An analysis of firm-specific resources and foreign direct investment in the United States. International Business Review 11, 431452. UNCTAD, 2006. World Investment Report 2006: FDI from developing and transition economies: implications for development. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. New York and Geneva. Wells, L.T., 1998. Multinationals and the Developing Countries. Journal of International Business Studies 29, 101114. Wernerfelt, B., 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 5, 171180. Winter, S.G., 2003. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal 24, 991995. Zaheer, S., Mosakowski, E., 1997. The dynamics of the liability of foreignness: a global study of survival in financial services. Strategic Management Journal 18, 439463. Zahra, S.A., Sapienza, H.J., Davidsson, P., 2006. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: a review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies 43, 917955.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Samsung MobilesDocument9 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Samsung Mobileslyf of GhaganNo ratings yet

- Hughes - Crony CapitalismDocument7 pagesHughes - Crony CapitalismAntonio JoséNo ratings yet

- Asia's Governance Challenge - Dominic BartonDocument8 pagesAsia's Governance Challenge - Dominic BartonDevyana Indah FajrianiNo ratings yet

- Samsung As A Silicon Valley Company: HBP Product ID: ST72Document18 pagesSamsung As A Silicon Valley Company: HBP Product ID: ST72Jose CastroNo ratings yet

- History: LG Corporation (Or LG Group)Document2 pagesHistory: LG Corporation (Or LG Group)huyytran660No ratings yet

- South Korea's Economic Development, 1948-1996 (Seth, 2017)Document21 pagesSouth Korea's Economic Development, 1948-1996 (Seth, 2017)Mauricio Casanova BritoNo ratings yet

- QQ - Data Pin Flyback - Persamaan - FuncsionDocument45 pagesQQ - Data Pin Flyback - Persamaan - FuncsionMukrom ElectronikNo ratings yet

- Hyundai and Kia engine piston ring specificationsDocument2 pagesHyundai and Kia engine piston ring specificationsВладимир АнаймановичNo ratings yet

- The Korean MiracleDocument20 pagesThe Korean MiracleDivya GirishNo ratings yet

- SAMSUNGDocument40 pagesSAMSUNGcommerceprist3No ratings yet

- Park Chung-Hee and The Economy of South KoreaDocument17 pagesPark Chung-Hee and The Economy of South KoreaBorn AtillaNo ratings yet

- North America's Diverse MarketplacesDocument36 pagesNorth America's Diverse MarketplacesPhan PhanNo ratings yet

- 11 Understanding Samsungs Diversification Strategy The Case of Samsung Motors IncDocument17 pages11 Understanding Samsungs Diversification Strategy The Case of Samsung Motors IncSunita NairNo ratings yet

- Secrets of SovereignDocument13 pagesSecrets of SovereignredcovetNo ratings yet

- The Journey of Cultural Globalization in Korean Pop MusicDocument16 pagesThe Journey of Cultural Globalization in Korean Pop MusiccpbelenNo ratings yet

- Bringing Down The PresidentDocument6 pagesBringing Down The PresidentAiman NiaziNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of The Chaebol and The Origins of The Chaebol Problem (Lim, 2014)Document18 pagesThe Emergence of The Chaebol and The Origins of The Chaebol Problem (Lim, 2014)Mauricio Casanova BritoNo ratings yet

- Listado Repuestos JACDocument6 pagesListado Repuestos JACRuben MedinaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Malaysia in Historical PerspectiveDocument36 pagesCorporate Malaysia in Historical Perspectivedaisuke_kazukiNo ratings yet

- Study Material National PowerDocument21 pagesStudy Material National PowerHuzaifa AzamNo ratings yet

- xh6xs 8cqq9 PDFDocument41 pagesxh6xs 8cqq9 PDFManoj YadavNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Samsung Group Under Lee Kun-HeeDocument110 pagesThe Evolution of The Samsung Group Under Lee Kun-Heeericchico362No ratings yet

- CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIESDocument6 pagesCORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIESHM.100% (1)

- Daewoo Express - Lahore To KarachiDocument2 pagesDaewoo Express - Lahore To Karachiزھیر طاہرNo ratings yet

- SamsungDocument6 pagesSamsungRahmad Nadzri100% (1)

- South Korea's Economic Growth and Indicative PlanningDocument8 pagesSouth Korea's Economic Growth and Indicative PlanningCatherine R. IronsNo ratings yet

- India Import Refrigerator Feb 19Document161 pagesIndia Import Refrigerator Feb 19ajayNo ratings yet

- Study of Asian Financial Crisis 1997Document26 pagesStudy of Asian Financial Crisis 1997Sudeep Sahu100% (1)

- A Project Report OnDocument57 pagesA Project Report Onabhinavdixit42444No ratings yet

- Samsung Mini CaseDocument8 pagesSamsung Mini CaseJoann Jeong50% (2)