Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2006 - ATA Annual Conf Proceedings - Back To School-Back at The Office (School and Office Supplies) - Moskowitz

Uploaded by

Andre MoskowitzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2006 - ATA Annual Conf Proceedings - Back To School-Back at The Office (School and Office Supplies) - Moskowitz

Uploaded by

Andre MoskowitzCopyright:

Available Formats

The Real Dictionary will give all the words that exist in use, the bad words as well

as any. The Real Grammar will be that which declares itself a nucleus of the spirit

of the laws, with liberty to all to carry out the spirit of the laws, even by violating

them, if necessary. . . . These States are rapidly supplying themselves with new

words, called for by new occasions, new facts, new politics, new combinations. Far

plentier additions will be needed, and, of course, will be supplied. . . . Many of the

slang words are our best; slang words among fighting men, gamblers, thieves, are

powerful words. . . . The appetite of the people of These States, in popular speeches

and writings, is for unhemmed latitude, coarseness, directness, live epithets,

expletives, words of opprobrium, resistance. This I understand because I have the

taste myself as large, as largely, as any one. I have pleasure in the use, on fit

occasions, of

__

traitor, coward, liar, shyster, skulk, doughface, trickster, mean cuss,

backslider, thief, impotent, lickspittle. . . . I like limber, lasting, fierce words. I like

them applied to myself

__

and I like them in newspapers, courts, debates, Congress.

Do you suppose the liberties and the brawn of These States have to do only with

delicate lady-words? with gloved gentleman words? Bad Presidents, bad judges, bad

clients, bad editors, owners of slaves, and the long ranks of Northern political

suckers (robbers, traitors, suborned), monopolists, infidels, . . . shaved persons,

supplejacks, ecclesiastics, men not fond of women, women not fond of men, cry down

the use of strong, cutting, beautiful, rude words. To the manly instincts of the people

they will be forever welcome.

Walt Whitman, American poet, c. 1852

3

TOPICS IN SPANISH LEXICAL DIALECTOLOGY: BACK TO SCHOOL / BACK AT THE

OFFICE

Andre Moskowitz

Keywords: Spanish, regionalisms, terminology, dialectology, lexicography, sociolinguistics, school

and office supplies.

Abstract: This paper contains information on the words used in different varieties of Spanish for

certain school and office supplies.

1

INTRODUCTION

This article somewhat resembles an international tourists guidebook except that instead of telling

you, the reader, what you can expect to experience in different countries with regard to mountains,

beaches, parks, cathedrals, museums, hotels, restaurants, store hours, currencies, government

authorities, local customs, weather and the like, it will tell you things about the language you will

encounter if you travel to different parts of the Spanish-speaking world. Well, this is indeed an

exaggeration. It will tell you about a very small subset of the language you will run into, namely,

some of the terminology relating to school and office supplies. This paper also has something in

common with international cookbooks that bring home exotic recipes from far-off places, except that

the platos tpicos, in this case, are not dishes but words

__

words and their meanings

__

a linguistic

smorgasbord, kaleidoscope or maelstrom of regional flavors and delights. In addition, this study can

be considered an example of investigative journalism except that what is being researched, exposed,

and debated is not the what and the wherefore of conflicts, politics, feats, disasters or other current

events, but of language use.

The primary goal is to describe early 21st century lexical usage in the Spanish-speaking world for

a series of school- and office-supply items whose names vary diatopically or by region. Secondary

objectives include addressing sociolinguistic issues, such as attitudes held by Spanish speakers from

different regions toward the relevant terms and variants, examining cases in which a lexical change

may be in progress (one term rising and another declining or dying out), and exploring a few

questions involving the history of the Spanish language, that is, the histories of its different varieties.

Lastly, I will review some of the relevant definitions of the 2001 edition of the Spanish Royal

Academys Diccionario de la lengua, also known as the Diccionario de la Real Academia

(hereinafter DRAE), and make suggestions on how these definitions can be improved.

4

Topics

The following topics, referred to by their United States English names, will be discussed:

A) Writing, erasing and related: 1) chalk, 2) chalkboard or blackboard, 3) chalkboard eraser or

blackboard eraser, 4) crayon, 5) (magic) marker, 6) pen A - ballpoint pen or regular pen, 7)

pen B - fountain pen, 8) pencil A - regular pencil, 9) pencil B - mechanical pencil, automatic

pencil or self-sharpening pencil, 10) pencil eraser and/or pen eraser, 11) pencil sharpener.

B) Fasteners and related: 1) rubber band, 2) staple (noun), 3) stapler, 4) staple remover, 5)

thumbtack, 6) paper clip.

C) Miscellaneous: 1) paper punch or hole punch, 2) ink pad or stamp pad, 3) notebook A - spiral

notebook, 4) notebook B - loose-leaf notebook or (three) ring binder, 5) pencil case, 6) file

folder, 7) briefcase.

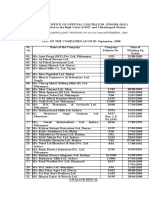

Formatting Conventions in the Terms by Country Tables

Each section of this paper addresses one of the topics outlined above in A) Writing, erasing and

related, B) Fasteners and related, and C) Miscellaneous and contains a Terms by Country table

consisting of countries in the left-hand column and terms and fractions in the right-hand column.

The denominators in these fractions represent the total number of responses from a specific country

for a given item and the numerators indicate the number of informants or respondents from that

country who gave a particular response. Thus, part of the Terms by Country table for section A1,

CHALK, reads as follows:

SPAIN tiza (20/20).

MEXICO gis (54/56), tiza (7/56).

GUATEMALA yeso (14/15), tiza (3/15).

This is to be interpreted as, When asked to give the name or names used for chalk, 20 out of 20

Spaniards queried indicated tiza, 54 out of 56 Mexicans said gis, 7 out of 56 Mexicans gave tiza, 14

out of 15 Guatemalans said yeso, and 3 out of 15 Guatemalans offered tiza. As we see in the

preceding example, some respondents offered more than one term for a given item and therefore the

sum of the fractions corresponding to each country is often greater than one.

The section on chalk will demonstrate that tiza is the most commonly used term for this item in over

75% of the Spanish-speaking countries (see section A1 below). We can therefore consider tiza to

be General Spanish usage, the most neutral Spanish word for this item, or the so-called

international standard term. In contrast, gis and yeso are commonly used in the sense of chalk in

relatively small subsets or pockets of the Spanish-speaking world, and thus these usages can be

viewed as regional. To distinguish regionalisms such as gis and yeso (chalk) from General Spanish

terms such as tiza, the former will be written in italics and the latter in regular letters in the Terms

by Country tables.

Because gis and yeso were offered by at least 50% of the respondents from Mexico and Guatemala,

respectively, they will also be considered majority regionalisms and written in boldface and italics

5

to highlight their importance; other regionalisms presented in this study that were offered by less

than 50% of the respondents queried will appear in italics only.

In examining the data for chalk presented above, we also note that tiza was offered by 20% or less

of the respondents from Mexico and Guatemala and this usage is therefore deemed a marginal

response in these two countries. To underscore its infrequent use among respondents from Mexico

and Guatemala, tiza is written in small print in the corresponding lines of the table; tiza, however,

appears in regular-sized letters next to Spain where it is the dominant term.

Responses and Respondents

For each of the 24 items listed above in A) Writing, erasing and related, B) Fasteners and related,

and C) Miscellaneous, responses were obtained from native speakers of Spanish from Spain and the

19 countries in Latin America that have Spanish as a principal official language.

The amount of data collected from respondents from each of the 20 Spanish-speaking countries

varies considerably. The initial goal was to obtain between 10 and 20 responses for each item from

each country, but the actual numbers ended up varying because not all respondents were asked all

questions, not all those who were asked a question were able to answer it, and some of the written

responses had to be discarded because they were illegible. Sometimes I also went back and queried

additional respondents from specific countries on specific topics when I felt the data initially

collected were inconclusive and I wanted to probe specific issues. In addition, I received over 50

responses from Mexican respondents due to the fact that I happened to attend a two-day symposium

in Monterrey, Nuevo Len, Mexico in October of 2005 at which I attempted to obtain information

from about 75 mostly Mexican translators, interpreters, educators and literary critics.

I collected data from respondents by a combination of one-on-one, face-to-face interviews and

through written responses to questionnaires that were both pictorial and text-based. The same

questions were asked in both the interviews and the questionnaires by means of the same images;

the questionnaires used arrows and written cues that were similar to the oral prompts employed in

the interviews. For example, with the set of items consisting of the chalk, the chalkboard, and the

chalkboard eraser, respondents were shown a picture of a wall-mounted chalkboard with an eraser

and a piece of chalk on the chalkboards shelf; in the interviews respondents were asked the

following questions while I pointed to the corresponding item:

Question 1: Cmo se llama esto donde uno escribe en el saln de clases (or en el aula)?

Answers: Pizarra, pizarrn, tablero, encerado.

Question 2: Cmo se llama esta cosa blanca (or esta barrita blanca) con que se escribe en la

pizarra (or en el pizarrn, el tablero, el encerado)? I would use whichever term for chalkboard

the respondent had previously given in answering question 1.

Answers: Tiza, gis, yeso.

Question 3: Y cmo se llama esto para quitar lo escrito con tiza (or con gis, or con yeso)?

Answers: Borrador, almohadilla, mota.

The percentages of respondents who were questioned using each of the two methods

__

oral interview

or pictorial/text questionnaire

__

also varied somewhat by country. More data were obtained through

written responses to pictorial questionnaires from respondents from Spain, Mexico, Cuba, Puerto

6

Rico, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Argentina and Chile, whereas interviews were the source of much

of the data from the Central American countries, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Bolivia,

Paraguay and Uruguay. This discrepancy was primarily due to logistical reasons and happenstance:

The native speakers of Spanish I have met over the years, both in the United States where I live and

abroad, and those I see at talks, conferences and symposiums, generally hail from the first set of

(mostly larger) countries, whereas to contact people from the second set of (mostly smaller)

countries I generally had to actively seek out potential respondents in the waiting rooms of their

respective consulates in San Francisco, California, and New York City.

Respondents who completed the pictorial questionnaires in writing were mostly translators,

interpreters, academics, and other highly educated individuals, and they were specifically asked

about their background and work experience, whether they had lived in any other Spanish-speaking

country for more than six months, and sometimes their age. People who answered questions orally,

in contrast, were selected at random from among those who happened to be available at the

consulates when I paid my visits. Because the interviewees were not specifically asked about their

backgrounds, their educational levels are not known with any certainty. However, I was able to

observe respondents speech and take a guess at the amount of schooling they had probably

received. This was aided by the fact that many respondents had a desire to provide more information

than I had requested and would frequently offer long explanations about the purpose and operation

of the items they were shown, especially when they had difficulty coming up with a name for the

object. Based on their pronunciation, morphosyntax, and vocabulary, I believe the range of

educational levels of those interviewed orally was fairly broad, everything from highly educated

individuals with graduate degrees to those who had perhaps only a middle-school diploma. I also

queried some who appeared to have even less formal education, perhaps only some primary school,

but I obtained little data from them for the simple reason that they were generally unable to answer

many of the questions.

The geographic distribution of the respondents within each country was also rather limited. In most

cases, the majority came from their countrys capital or another large city. For example, the

overwhelming majority of Argentine and Peruvian respondents came from Buenos Aires and Lima,

respectively. The reason for this is that it is a lot harder to find people from San Salvador de J ujuy,

J ujuy, Argentina or from Cerro de Pasco, Pasco, Peru outside of J ujuy and Pasco, respectively, than

it is to find Porteos and Limeos outside of Buenos Aires and Lima; Bonaerenses and Limeos can

be found scattered across the globe, almost anywhere. In the case of Mexico, more respondents came

from Monterrey and the northeast border states than from any other region, although there were also

quite a few who hailed from Mexico City, Guadalajara, Puebla, Veracruz and other large cities.

Perhaps ironically, the country from which I was able to obtain the greatest geographic diversity of

respondents was Spain, and yet little variation was encountered for school- and office-supply

terminology in the different regions of the madre patria.

How representative and valid the data are is certainly open to question. Unlike in the lexical studies

that are part of the Proyecto de estudio coordinado de la norma lingstica culta de las principales

ciudades de Iberoamrica y de la Pennsula Ibrica (the first of which was J uan Miguel Lope

Blanchs Lxico del habla culta de Mxico, published in 1978), the answers in the present study

were not all obtained from a pool of respondents who come from the same city and whose

educational levels are both known and similar. Further research will be needed to determine how

and to what extent school- and office-supply terminology varies intra-nationally, or within nations,

7

among the different sociocultural, age and gender groups of each society, and diachronically, that

is, over time.

Spelling and Variants

To some extent, the existence of written and/or spoken variantssuch as sacapuntas and

sacapuntais noted in the Terms by Country sections through the use of parentheses: In this case,

both variants are represented by sacapunta(s) whenever some respondents from a given country

offered the form with a word-final s and others gave the form without one. Throughout this article

there are also paragraphs entitled Spelling & Variants which explain in greater detail the different

written and spoken forms offered by respondents that could be considered variants of a single term.

While sacapuntas is the only spelling for this term listed in the DRAE (and in many other Spanish-

language dictionaries), large numbers of native Spanish speakers, including highly educated ones,

say and write sacapunta without a final s, and some even write the term as two words, saca punta(s),

or as a hyphenated word, saca-punta(s).

Some of you may chuckle or scoff at many or all of these unofficial variants of the word

sacapuntas, and may even be thinking to yourselves pero qu brutos que son! in reference to those

who use them, but in fact this variation can be attributed to several mitigating factors: On the one

hand, many Spanish speakers write and pronounce the word sacapunta, with no final s, that is, with

no regular s ([s]), no Castilian s (apical s or []), nor any aspiration ([h]). Secondly, there is a fair

amount of general uncertainty regarding how to spell infrequently written compound terms like

sacapunta(s) since people tend to talk about pencil sharpeners much more often than they write the

word. With regard to semantics, it is true that over the course of its lifetime a pencil sharpener may

sharpen many points (durante su vida til, un sacapuntas puede sacar muchas puntas), but at any

given moment it sharpens only one (un sacapunta saca una sola punta a la vez). Thus neither form

is semantically more precise than the other. There are even some Spanish speakers who believe that

a sacapunta is a hand-held pencil sharpener that has only one hole, like the one shown in figure A11,

and that a sacapuntas is a hand-held one with two different holes for two different sizes of pencil,

or a pencil sharpener with a crank that has multiple holes like the one shown in figure A11', though

most Spanish speakers would probably dispute any claim that sacapuntas and sacapunta refer to

different types of pencil sharpeners. Also, in defense of sacapunta, it should be noted that the DRAE

lists and accepts both sacabocados and sacabocado (hole punch), and since these devices likewise

make many holes over time but sometimes only one at a time, the argument can easily be made that

sacapunta is no less valid than sacabocado. In the case of sacahoyo(s) and abrehueco(s) (hole

punch), no form of these words appears in many dictionaries, they are written even less often than

sacapunta(s), and many speakers who use the latter terms, including highly educated ones, show an

even greater variation and uncertainty concerning the terms correct spelling.

Somewhat similar variation issues exist with many English-language compound terms. To cite just

a few examples from the school- and office-supply domain, we note that paper clip, rubber

band, thumb tack, and push pin are often written as one word

__

paperclip, rubberband,

thumbtack, and pushpin, respectively

__

and if you do an Internet search of the different forms

of these words, you will get hundreds of thousands (and in some cases millions) of hits for each.

Which spellings are preferable? On the one hand, it can be argued that a paper clip is merely one

specific type of clip, used with paper, among others in the general category of clips. This might

suggest that paper should be a simple adjective modifying the noun clip and that the compound

8

term should be written as two words. On the other hand, in the minds of many speakers a paperclip

is its own item, separate and apart from other clips. This may explain why paperclip is so often

written as one word, and perhaps even why the Spanish word clip mostly refers to paper clips rather

than to other types: In the linguistic transfer from English to Spanish the Anglicism clip tends to be

narrower in meaning and more specific, although theoretically it can refer to any type of clip. Within

the field of computers, two of the most ubiquitous examples of this type of variation are log on

and log in, both of which are frequently written as one word, perhaps even when they are verbs,

though not in the past tense (she logged on, not she *logonned), or in a progressive tense (Im

logging on, not Im *loggingon, or Im *logonning).

Comparing Other Sources

I have checked a number of regional Spanish dictionaries

__

diccionarios de guatemaltequismos, de

bolivianismos, etc.

__

to see if any of them contained information that contradicted the findings of this

study. Most lacked definitions of the respective countrys regional school- and office-supply

terminology, and others confirmed some of the assertions made by this studys respondents.

However, a few sources had definitions that contradicted, expanded upon or modified the

information obtained from respondents. I have also compared my data with those of the Lxico del

habla culta studies to see how the educated usage presented for specific cities in those works

matches up with what I encountered for the corresponding countries as a whole. However, for the

most part I only cite or reference entries from lexicographical works or sections of the Lxico del

habla culta studies that contradict or go beyond that which the data from this study suggest is

prevalent, and when published sources conflict with the results of this study, I pose basic usage

questions. In citing the Lxico del habla culta studies, I indicate the authors last name and the page

number in parentheses, but when referencing dictionaries, I do not list the page number since in all

of the lexicographical sources the words appear in alphabetical order. See endnote 12 for

information on an online source called Varilex (Hiroto Ueda et al).

Real Academia Regional Review

The Real Academias dictionary, or DRAE, currently in its 22nd edition, has played an even more

central role in the lives of Spanish speakers than the Oxford, the Websters or other important

English-language dictionaries have in the lives of English speakers, and unlike the leading British,

Australian, Canadian or American dictionaries, each of which has more of a regional following, the

DRAE is regularly consulted by Spanish speakers from all Spanish-speaking countries. This is due

in part to a dearth of high-quality general dictionaries published in Spanish America, and in part to

a tradition in Spanish America of culturally and linguistically worshiping the mother country in

general and the DRAE in particular. While some would propose simply breaking with this

tradition

__

i.e. tossing the DRAE (or relegating it to a box in the closet or the garage), and in its place

writing at least 20 national general Spanish-language dictionaries, one each from Guatemala,

Honduras, etc.

__

this is not easily done or likely to be achieved in the near future in the case of most

Spanish-speaking countries. Nevertheless, in the last decade or two, Mexico, by far the largest

Spanish-speaking country in population, has made significant strides in creating its own

lexicographical self-sufficiency with the publication of the Diccionario del espaol usual en Mxico

(Lara Ramos 1996) and its predecessors, the Diccionario bsico del espaol de Mxico (Lara Ramos

1986) and the Diccionario fundamental del espaol de Mxico (Lara Ramos 1982), as well as the

Diccionario inicial del espaol de Mxico (vila 2003). However, even these works are all abridged

9

dictionaries. (Los diccionarios de Lara Ramos y de vila son excelentes y representan un gran paso

adelante, pero lo que realmente necesitamos para cada pas hispanohablante son diccionarios

completos, ntegros

__

o al menos no abreviados

__

, no diccionarios bsicos, ni iniciales, aunque por

ah supongo que se ha de empezar.) And since Mexicos lexicographical autonomy is a special case,

an exception that confirms the rule, I would therefore recommend that for the time being we Spanish

speakers continue to uphold the practice of consulting the DRAE and letting it serve as our primary

guide in matters concerning the Spanish language, but that this tradition be made more functional

by proposing specific changes to the dictionary that are motivated by the following three general

desires:

a) That the DRAE describe items more precisely in its definitions;

b) That the DRAE use metalanguage in its definitions that conforms more to General Spanish

than to Peninsular Spanish usage (this may be a sueo quijotesco); and, most importantly,

c) That the DRAE paint a more accurate picture of the Spanish languages international

contours and landscape.

This articles Real Academia Regional Review sections present an evaluation of the 2001 edition

of the DRAE and grade this dictionarys definitions of specific terms using the following grading

scale:

A Corresponding definition, correct regions. This grade is given when the DRAE defines the

term as used in a particular section of this article and correctly indicates the countries and/or

regions in which the term is used in this sense.

B Corresponding definition, incorrect regions. This grade is given when the DRAE defines the

term as used in the section and specifies a region or regions but does not specify them

correctly. Its definition either fails to include regions in which the usage occurs or includes

regions where the usage does not occur. However, the grade of B is raised to an A if the

DRAEs definition is appropriate, Amr. (Amrica, that is, Spanish-speaking Latin

America) is specified in the definition, and the term is used in 10 or more (over 50%) of the

19 Spanish-speaking Latin American countries.

C Corresponding definition, no regions specified. This grade is given when the DRAE defines

the item in question but does not specify any countries or regions in which the term is used

in this sense. In essence, it fails to identify a regional usage as regional. However, the grade

of C is raised to an A if the term is used in at least 10 (at least 50%) of the 20 Spanish-

speaking countries.

D No corresponding definition. This grade is given when the DRAE does not include in its

definition of the term a sense that corresponds to the item in question.

F Term not listed. This grade is given when the DRAE does not list the term at all.

The DRAEs definitions themselves are quoted in these sections so that the reader can follow the

analysis that went into their evaluations. When citing DRAE definitions of nouns, I do not include

the gender specification m. or f. unless the words gender is not transparent to most Spanish

speakers, as in the case of gis or birome, or is specifically a dialectal issue, as occurs with a word

like chinche. Terms that were offered by fewer than three respondents are generally not graded, and

definitions of some relevant words that were not given by respondents are also presented. Thus not

all terms indicated by respondents are graded and not all words whose definitions are quoted were

offered by respondents. When, in my judgement, the category under which a definition rightfully

10

falls is debatable, the grade assigned (A, B, C, D or F) is followed by a question mark, or is

presented as one or more alternatives such as C or D?

In addition to the grades assigned, an overall score or grade point average (GPA) for each topic is

calculated based on the American-style 4-point grading system in which A =4.0, A! =3.7, B+=

3.3, B =3.0, B! =2.7, C+=2.3, C =2.0, C! =1.7, D+=1.3, D =1.0, and F =0.0. As indicated

above, no plus or minus grades are assigned to the coverage of each term, but the plus/minus grading

system is used to calculate the overall GPA for each topic. Thus in the Real Academia Regional

Review section corresponding to CHALK, in which the DRAE receives the marks of gis (no region

specified =C =2.0), tiza (General Spanish term =A =4.0) and yeso (no corresponding definition

=D =1.0), the grade point average or GPA is the sum of the grades (7) divided by the number of

words graded (3). Thus, 7 3 =2.33, which is just barely above a C+, but since this figure falls in

between two grades we round it up to the next highest mark and the grade ends up being a B! (2.7).

Because we round up the GPA score if it falls between grades, and because we also calculate the

GPA on the basis of the highest grades when the grades given are in doubt (e.g. A or D?), there

is a certain amount of GPA inflation involved. On the other hand, it can be argued that the grading

system is too harsh since if the DRAE does not list a term such as lpiz de mina, it will also not list

its variant lpiz mina and therefore receives an F twice for what is essentially a single defect, which

naturally results in a lower GPA. Similarly, the DRAE gets dinged twice for not including pilot

or pilot when both are really just different forms of the same word.

As will be shown in the individual Real Academia Regional Review sections, the DRAE often

receives poor marks for its definitions, especially those which relate to Spanish American usage. In

the DRAEs defense, it can be said that attempting to describe usage in the entire Spanish-speaking

world can be a daunting task, even in the case of a domain such as school and office supplies that

on each national level appears to be fairly standardized. Many theories can be advanced regarding

the causes of the DRAEs poor performance, but I believe the following are three key factors:

a) J ust as some governments have poor cultural, diplomatic, strategic and military

intelligence in parts of the world, a lack of knowledge by DRAE authors and editors of the linguistic

situation on the ground, that is, of actual usage in the different Spanish American countries, means

that the DRAE has a poor grasp of language matters in Spanish America.

b) Despite the claim in the DRAEs Prembulo that they receive and seriously consider large

amounts of input and information from the corresponding academies, an examination of its

definitions suggests a reluctance to engage in an active, frank and open collaboration with Spanish

Americans on the Dictionary project.

c) A lack of awarenesswhich some might consider akin to eurocentrism, glossocentrism,

or perhaps just plain old-fashioned arroganceon the part of the DRAEs editors that leads them to

believe that their lack of knowledge and experience with the Spanish language, as it is used in

different parts of the New World, is not a serious impediment to their accurately describing Spanish

American usage.

Until such time as the Real Academias editorial staff recognizes these organic deficiencies and

resolves to do the necessary investigation and consultation so that it can scale the mountain with the

benefit of the multiple perspectives, analyses, knowledge bases and equipment that are needed to

accomplish this feat without suffering frostbite (or worse casualties), its dictionary is likely to be

plagued by the same basic condition and much of the information it presents on New World Spanish

11

will continue to be at variance with actual usage. Any other publishing house, whether located in

Madrid, Mexico City, Managua, Miami, Bogot or Buenos Aires, that seeks to write a pan-Hispanic

dictionary of the Spanish language should heed the same warning and be prepared to get out and do

the necessary investigation, consultation and legwork.

*

* *

Marginal Responses

Marginal responses, those offered in this study by 20% or less of the respondents from specific

countries, appear to fall into different categories and to occur for different reasons. Some may be

cases of respondents misinterpreting an image or question and offering a term that refers to a related

but different object than the one targeted. For example, some of the respondents who offered

tachuela in the sense of thumbtack may have thought the image shown to them was just a small

tack since thumbtacks and tacks look somewhat similar, and they may have been unclear on the

difference between the two objects. Yet the large number of Spanish speakers, including dozens of

educated ones, who indicated tachuela in response to the question about the thumbtack also suggests

that for many Spanish speakers tachuela is in fact the name they use for this object, and was not

offered as a result of confusion or misunderstanding.

In other cases, marginal responses may reflect speakers lack of communicative competence in

some aspect of the school- and office-supply domain, which simply means (with regard to the

lexicon) that they do not know one of their own countrys official words for a given object. If a

person being asked to identify a picture of an ink pad does not know one of the real names for this

item, he or she may not want to lose face by answering La verdad es que no s cmo se llama eso

and may instead decide to take a stab at it and try to come up with some name that sounds like a

reasonable possibility. However, based on relatively small amounts of data, it is sometimes difficult

to distinguish between cases in which speakers lack linguistic competence and those in which they

simply use a less precise term. For example, in part because tinta refers to ink, it is unlikely that

many highly educated people would accept tinta para sello(s) as a legitimate term for ink pad, but

the fact remains that this metonymic term appears to be widely used in the sense of ink pad by large

numbers of Spanish speakers who, for whatever reason, do not know one of the correct, real or

official words for this object. Other marginal responses may involve terms that some respondents

do use regularly in the sense in question but which are atypical of mainstream usage in their speech

community. Many are hapax legomena

__

words that in this study were offered in a particular sense

by only one respondent from a given country or region

__

and in the absence of other supporting

evidence these should be given little or no weight. Even terms that were offered by a handful of

respondents should be viewed with a healthy skepticism, especially if three or four times that

number indicated a different usage. On the other hand, if 4 out of 32 Colombians offered plumero

(ballpoint pen), but all 4 were Costeos (Colombians from the Atlantic Coast region) and they

were the only Costeos queried, then we have a situation in which 100% of Colombians from a

specific region have indicated a specific usage. The results of such a small sampling are not

statistically significant, but they do suggest that we may indeed be on to something and the next

logical step is to try to query as many Costeos as possible, preferably from different parts of the

Costa, to see what pattern emerges.

12

Perhaps the most frequent type of marginal response occurs when respondents offer the General

Spanish term either instead of or alongside their countrys regional word, sometimes in an effort to

suppress or reject the regional term. For example, some Mexicans and Guatemalans may opt to say

tiza instead of gis or yeso in order to use a word that enjoys international prestige and recognition

and to avoid using one that they perceive (or believe others may perceive) as regional, local or

unsophisticated. In some cases, people do this in an attempt to distinguish themselves from their

more plebeian fellow citizens and to show that they belong to las clases ilustradas.

It is also important to bear in mind that the language recorded in this study was not spontaneous, as

it was clear to respondents that a researcher was writing down their responses. And perhaps even

more so than in the case of phonetics, phonology and other aspects of pronunciation, with the

lexicon most speakers have a considerable ability to choose their words depending on what the

situation is, who their interlocutors are, and what the image and identity they are trying to project

is. For example, some Mexicans and Guatemalans who offered tiza may have felt self-conscious

about using gis or yeso and may have wanted to take on a cosmopolitan or international air in the

interview or on the questionnaire through their use of the General Spanish term. Other Mexicans and

Guatemalans, in contrast, may really say tiza in their everyday speech when speaking with

compatriots, although to use the international standard instead of the national standard would

generally entail a deliberate and conscious choice. Also, by not using the term for a given item that

is most frequently used in their own country, speakers run the risk of being labeled as odd, snobbish,

extranjerizante and perhaps even unpatriotic. This can easily happen to a Mexican who says tiza

instead of gis, or to an Argentine who says piscina instead of pileta (swimming pool).

Majority Regionalisms

Majority regionalisms, those offered by 50% or more of respondents and appearing in boldface and

italics in the Terms by Country tables, are likely to be of primary interest to readers of this article,

regardless of their attitudes toward regionalisms.

For example, if you are a regionalism enthusiast (or a dialectologist), then majority regionalisms

represent exciting and exotic manifestations of Spanish that depart from the run-of-the-mill,

international-standard or textbook terminology that students of Spanish as a second language learn

and that their teachers are instructed to teach. At the same time these regionalisms constitute

mainstream usage in the speech communities in question. In other words, usages like gis and yeso

(chalk), though regional, can not be easily dismissed as ones that are only heard in certain small

communities, or are primarily used by isolated groups of rural, uneducated and/or elderly

individuals. On the contrary, the large percentage of this studys Mexicans and Central Americans

who offered gis or yeso (chalk) suggests that millions of Spanish speakers from the countries in

question, including highly educated persons, use these terms everyday. This belief is based on

limited data and the unscientific but often reliable principle of cuando el ro suena agua lleva or

cuando el ro suena (es porque) piedras trae. However, as the variants of this refrain suggest, the

meaning of a rivers sound is open to interpretation.

Those of you who take the view that Spanish regionalisms are an impediment to uniformity, a thorn

in our languages side, and even a disease for which a prophylactic ought to be developed and

applied, will find the terms in boldface and italics useful as they will allow the culprits to be easily

identified and held up for public scorn by like-minded individuals. Vilifying regionalisms, or leading

13

a crusade against them, however, may not be successful in dislodging or eliminating them,

notwithstanding the advances of modern international media and communications that are supposed

to globalize and homogenize our societies, or at least those societies which share a common

language, in this case Spanish.

The pervasiveness of the media, though possibly decreasing and diluting regional differences within

nations, may in some cases be strengthening regional differences between and among countries:

Nationalism, as the last century has shown, is a powerful force, and language is one of its primary

manifestations. This last point is important for the study of dialectology as it poses the general

question of what the future holds for usages that are regionally marked within a given country. For

example, since words for hopscotch are not products that are bought and sold, or concepts that are

taught in federally controlled school systems or referred to in national media, regionally marked

names for this game can easily survive and co-exist within a single country. The future for most

school- and office-supply terms that are regionally weighted within a country, in contrast, is

probably not very bright.

Readers of this article who have a neutral view of Spanish regionalisms and just want to know who

says what and where will also want to focus on the majority regionalisms and contrast them with the

international standard so as to understand language usage on a pan-Hispanic level. The regionalisms

presented here, and especially the majority regionalisms, will also be of interest to those of you who

are curious to find out how your own vocabulary matches up with that of other Spanish speakers.

And you may be surprised to learn which of your own usages are regional and sound odd to other

Spanish speakers. Hopefully, you will also gain a better understanding of why some of your

Spanish-speaking friends usages seem strange or foreign to you.

A marshmallow by any other name would smell as cloyingly sweet and, unlike a rose, really does

have many names in Spanish. Yet we all have our biases when it comes to language varieties and

a sense of aesthetics regarding language use, including proper terminology: Some names smell

just right to us while others appear to give off a foul odor. However, if we can avoid getting caught

up in wanting everyone to speak the same way, we may find lexical diversity and variation to be

quite enriching. We Spanish speakers can all appreciate classic Spanish terminology, such as tiza

(chalk), sacapuntas (pencil sharpener), or perforadora (hole punch), but sometimes we may

be in the mood for more offbeat and regionally marked usages such as gis, yeso, tajador, tajalpiz,

abrehuecos or taladradora.

14

15

16

17

18

A WRITING, ERASING AND RELATED

A1 CHALK

A1.1 Summary

Tiza is the General Spanish term. Gis is used in Mexico and yeso in northern Central America.

A1.2 Terms by Country (3 terms)

SPAIN tiza (20/20).

MEXICO gis (54/56), tiza (7/56).

GUATEMALA yeso (14/15), tiza (3/15).

EL SALVADOR yeso (16/17), tiza (3/17).

HONDURAS tiza (14/18), yeso (11/18).

NICARAGUA tiza (13/13).

COSTA RICA tiza (12/12).

PANAMA tiza (14/14).

CUBA tiza (17/17).

DOMIN. REP. tiza (13/13).

PUERTO RICO tiza (17/17).

VENEZUELA tiza (24/24).

COLOMBIA tiza (17/17), gis (3/17).

ECUADOR tiza (14/14).

PERU tiza (16/16).

BOLIVIA tiza (16/16).

PARAGUAY tiza (10/10).

URUGUAY tiza (10/10).

ARGENTINA tiza (22/22).

CHILE tiza (15/15).

A1.3 Details

General: Why did a Nahuatl-derived word, tiza, become the term for chalk in most parts of the

Spanish-speaking world, perhaps replacing and/or displacing Latin-derived gis and yeso?

(See the etymologies of gis, tiza and yeso in section A1.4 below.) And why did tiza

ironically not take root in New Spain/Mexico, the colony/country with the strongest and

most direct Nahuatl influence? How this apparent swap took place is not adequately

explained in the DRAE or in the Diccionario crtico etimolgico castellano e hispnico

(Corominas). Is it possible that during the beginning of the colonial period the conquering

Spaniards were so intent on eliminating Aztec language and culture in New Spain that they

managed to successfully suppress the Nahuatlism tiza(tl) and impose the castizo term gis,

and that tiza was still able to be transplanted back to Spain and prosper in most parts of the

Spanish-speaking world outside of Mexico where eliminating Aztec influence was not an

issue? Could this explain why gis took root and flourished in Mexico but is used only

vestigially in Colombia, Bolivia and perhaps Spain? Although this seems unlikely, it is an

intriguing theory.

19

Spain: Tiza (chalk) is clearly the dominant usage in Spain, but what are the characteristics of those

Spaniards

__

i.e. older Spaniards, Spaniards from certain regions, etc.

__

who when speaking

Spanish currently use other words for this item such as clarin, creta, gis or yeso? In this

study, tiza was the only term offered by all 20 Spanish respondents, but a couple of those

born before 1960 indicated that their parents use or used clarin in this sense, and the

DRAEs definitions of clarin, creta, gis and yeso (see section A1.4 below) suggest that

some of these terms are, or were, synonyms or quasi-synonyms of tiza. In the three Lxico

del habla culta studies involving Spanish cities (Madrid, Granada and Las Palmas de Gran

Canaria), small numbers of respondents

__

only 1 out of 12, 1 out of 16 and 1 out of 24,

respectively

__

indicated that creta, pizarrn or yeso were used in the sense of tiza, though

none offered clarin (Torres Martnez: 586; Salvador: 747; Samper Padilla: 479). The issue

of who in Spain uses terms other than tiza for chalk

__

when speaking Spanish

__

is one that

warrants further study; the words guix and clari, I am told, are used in Cataln and/or

Valenciano.

Mexico: Gis is not only by far the most frequently used term in Mexico, it also appears to enjoy a

very high level of acceptance among educated Mexicans vis--vis General Spanish tiza.

Statements such as Tiza lo dicen en Espaa y otros pases, aqu en Mxico decimos gis

were made often and unapologetically by educated Mexicans in this study. This acceptance

of gis is also supported by the fact that both the Diccionario del espaol usual en Mxico

(Lara Ramos) and the Diccionario inicial del espaol de Mxico (vila) define gis in

neutral, unmarked terms and either do not list tiza (chalk) or specifically define it as a

foreign usage. The acceptance of gis in Mexico is in stark contrast to the situation in

Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras where another regional term, yeso, is used.

Guatemala, El Salvador & Honduras: Yeso is the dominant term in Guatemala and El Salvador and

is a serious competitor of tiza in Honduras. Educated speakers from all three countries, some

of whom prefer tiza, tend to exhibit a fair amount of linguistic insecurity concerning the use

of yeso in the sense of chalk, and remarks by Guatemalans, Salvadorans and Hondurans such

as Le decimos yeso a la tiza, pero es incorrecto: el yeso es el material de que est hecha la

tiza reflect this view. See Attitudes toward tiza vs. alternate terms below.

Colombia: Tiza was offered by all respondents in this study, but 3 of them

__

2 Bogotanos and 1

Santandereano

__

also indicated that gis is used (or was used in the past) in the sense of a thick

piece of chalk for writing on individual, hand-held chalkboards on which elementary school

children used to do their schoolwork. Two of the Colombians who offered gis stated that

they believed this usage was either dead or dying, and in the Lxico del habla culta de

Santaf de Bogot study, published in 1997, 25 out of 25 educated Bogotanos offered only

tiza (Otlora de Fernndez: 838). However, the Nuevo diccionario de colombianismos

defines gis as the standard Colombian Spanish word for chalk (Haensch and Werner 1993a).

Was gis (chalk) standard Colombian Spanish in the 1980s and early 1990s when the team

of researchers led by Haensch and Werner were researching this variety of the language? If

this had been so, it seems unlikely that this usage could have virtually disappeared without

leaving a trace among so many respondents from both the Lxico del habla culta study and

the present study in such a short period of time. Also, my own memory from having lived

in Colombia in 1984-85 was that tiza was the term used for regular classroom chalk.

2

Bolivia: Is gis used in this sense in Bolivia and, if so, how frequent is this usage? None of the 16

respondents in this study offered it, but in the Lxico del habla culta de La Paz study, 2 out

of 12 educated Paceos indicated that gis was used in the sense of chalk, albeit less often

than tiza (Mendoza: 530).

20

Attitudes toward tiza vs. alternate terms: What can explain the fact that gis is fully accepted in

Mexico but yeso is a source of concern, and often embarrassment, among educated

Guatemalans, Salvadorans and Hondurans, a linguistic insecurity that manifests itself in a

rejection and sometimes even denial of their own usage? The following are some possible

explanations:

a) Because yeso has the closely related meaning of plaster in General Spanish, some

educated Guatemalans, Salvadorans and Hondurans may be genuinely (if illogically)

troubled by the fact that this term should be applied to both the material and the bar made

of a similar material, especially since such a good word (tiza) exists for the latter;

sometimes people are uncomfortable with polysemy. In contrast, Mexicos gis can not be

objected to on these grounds as it refers only to chalk.

b) The history of northern Central America is quite different from that of Mexico. In

Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras, military dictatorships, protecting the interests of both

small national oligarchies and United States corporations, and generally funded and trained

by the US military, have ruled over the course of most of their histories. Also, the civil wars

in Guatemala and El Salvador, which lasted for several decades until the 1990s and pitted

the elites, backed by the army, against campesinos and the indigenous populations, backed

by the guerrillas, were concluded with few substantive concessions or structural changes

made by the winning side (the elites). It is perhaps in part for this reason that in northern

Central America many members of the upper classes feel little affinity with or connection

to their respective countrys less fortunate masses, and have a strong desire to differentiate

themselves from the general population. In Guatemala, members of Indigenous groups also

tend to feel a great resentment toward and cultural disconnect from the urban Ladino

population. (Ladinos are those who identify themselves as racially Hispanic/Mestizo and

have a Western orientation.) In Mexico, in contrast, issues of class struggle were supposedly

solved (and buried) by the Mexican Revolution (1910-1928, armed phase), and the

ongoing revolution or institutional phase that followed in the succeeding decades, and

many aspects of the pueblos traditional culture are enjoyed and appreciated by Mexicans

of all social classes. In other words, although the contrast between haves and have-nots can

be just as stark in Mexico, the cultural divide is not seen as a chasm that has no bridges.

c) Mexico is a much larger country than Guatemala, El Salvador or Honduras, and

sometimes people from large former colonies do not care as much how their language use

is perceived by outsiders and tend to be less interested in imitating the usage of the mother

country.

3

A1.4 Real Academia Regional Review

DRAE grades: gis (C), tiza (A), yeso (D). GPA = B!

DRAE definitions: tiza, (Del nahua tizatl). Arcilla terrosa blanca que se usa para escribir

en los encerados y, pulverizada, para limpiar metales; clarin, (Del fr. crayon, quiz con infl. de

claro). m. Pasta hecha de yeso mate y greda, que se usa como lpiz para dibujar en los lienzos

imprimados lo que se ha de pintar, y para escribir en los encerados de las aulas; gis, (Del lat.

gypsum, yeso). m. clarin; pizarrn, Barrita de lpiz o de pizarra no muy dura, generalmente

cilndrica, que se usa para escribir o dibujar en las pizarras de piedra.

Questions/Comments: Some Spanish-English dictionaries translate the terms tiza, clarin

and pizarrn as chalk, white crayon and slate pencil, respectively, and the DRAEs definitions

of the Spanish-language words indicate that they all refer to something that is used to write on

21

chalkboards but that they are not exact synonyms. Since the definition of gis cross-references the

reader to clarin and that of clarin does not refer the reader to tiza, a user of the DRAE is not

informed that gis and tiza are geosynonyms. The DRAE needs to add a sense of gis that corresponds

to chalk and include in it the regional specification Mx and perhaps also Col. and Bol. if

this usage is in fact common in Colombia and Bolivia; the evidence from this study and others that

is presented in sections A1.2 and A1.3 above suggests that the use of gis (chalk) is at best marginal

in these two countries.

The definition of tiza also needs to be expanded to include other uses for and types of chalk.

Compare the Diccionario inicial del espaol de Mxicos definition of tiza, which in addition to

describing standard chalk used with chalkboards, also includes senses corresponding to tailors chalk

and cue chalk used in pool and billiards: 2 Especie de tableta rectangular de color blanco que usan

los sastres para trazar lneas sobre las que van a cortar una tela: Marca con tiza la tela, para cortarla

despus. 3 Polvo de color azul que se pone en la punta de los tacos que se usan para jugar billar: Si

no pones tiza al taco no le vas a pegar bien a la bola (vila). Nowhere are these two important

uses of chalk mentioned in the DRAEs definition. In fact, the DRAEs definition of tiza needs to be

made more general so that the chalk described is not limited to a particular color and so that the

entry covers various common uses. For example, chalk dust, in addition to being used for cleaning

metal, as the DRAEs definition indicates, also has another very important use in carpentry, drywall,

masonry and other trades: By means of a device called a chalk line or a chalk reel that coats a

string with (typically blue or red) chalk dust, one snaps a chalk line to mark a straight line between

two points, often for the purpose of sawing or cutting boards, plywood, sheetrock, etc. Gymnasts

and other athletes also use chalk dust to absorb sweat so that their hands will not be slippery and

they will be able to catch and hold on to bars, balls, etc.

A2 CHALKBOARD or BLACKBOARD

A2.1 Summary

When referring to a chalkboard of the type attached to a wall, pizarrn is the most commonly used

term in 6 or 7 countries, pizarra in 4 or 5, and in about 7 or 8 others the two terms enjoy a healthy

competition. Spain, Panama and Colombia have more regional usages not commonly found

elsewhere.

A2.2 Terms by Country (4 terms)

SPAIN pizarra (20/20), encerado (6/20).

MEXICO pizarrn (57/57), pizarra (4/57).

GUATEMALA pizarrn (14/14), pizarra (1/14).

EL SALVADOR pizarra (11/16), pizarrn (9/16).

HONDURAS pizarra (15/16), pizarrn (4/16).

NICARAGUA pizarrn (12/14), pizarra (9/14).

COSTA RICA pizarra (15/15), pizarrn (8/15).

PANAMA tablero (14/14), pizarra (2/14), pizarrn (2/14).

CUBA pizarra (14/17), pizarrn (7/17).

DOMIN. REP. pizarra (13/15), pizarrn (10/15).

PUERTO RICO pizarra (17/17).

22

VENEZUELA pizarrn (21/24), pizarra (13/24).

COLOMBIA tablero (17/17), pizarra (4/17), pizarrn (3/17).

ECUADOR pizarrn (12/14), pizarra (2/14).

PERU pizarra (17/17), pizarrn (2/17).

BOLIVIA pizarrn (13/19), pizarra (10/19).

PARAGUAY pizarrn (10/10), pizarra (2/10).

URUGUAY pizarrn (10/10).

ARGENTINA pizarrn (22/22), pizarra (4/22).

CHILE pizarrn (11/16), pizarra (9/16).

A2.3 Details

General: The image shown to respondents in this study was a wall-mounted chalkboard of the type

used in classrooms, not a small, hand-held portable one or slate that students in the United

States once used (with a slate pencil), and no doubt still do

in many parts of the world.

Some respondents were also asked what they would call these hand-held chalkboards. The

results of this study suggest that most Spanish speakers use a single base term (e.g. pizarra,

pizarrn or tablero) for all types of chalkboard and make distinctions through modifiers. In

other words, they say pizarra grande vs. pizarra pequea or pizarra chica to distinguish

large ones from small ones. However, more research needs to be done to determine if some

speakers use two different base terms such as pizarrn (large chalkboard) vs. pizarra (small

or medium one), or possibly a tripartite distinction such as pizarrn (large, wall-mounted),

pizarra (medium, wall-mounted), and pizarrita (small, hand-held).

Spain: Pizarra (chalkboard) is the dominant usage in Spain but the following issues need to be

researched: What are the characteristics of those Spaniards who currently use the term

encerado, and what distinctions in meaning, if any, do different Spaniards make between

pizarra and encerado? Who, if anyone, in Spain currently uses tablero (chalkboard)? In

this study, some respondents said that they believed encerado is used more in Castilla and

other regions of northern and central Spain, and most of those who offered encerado were

in fact northern and central Spaniards born prior to 1960. Quite a few respondents from

eastern Spain (i.e. Mediterranean Spain) and from southern Spain (e.g. Andaluca) stated that

the term encerado is not commonly used in their regions. Others said that encerado is used

more by teachers, regardless of region, especially in phrases such as Al encerado! when

telling students to go up to the chalkboard, and that pizarra is used more by the general

population. Still other Spaniards claimed that the distinction between encerado (large

chalkboard) and pizarra (small hand-held chalkboard) used to be important at a time,

perhaps prior to 1960, when paper, notebooks and pens were too expensive and many

students would use hand-held chalkboards and chalk (or slate pencils) to practice basic

writing or math skills. They indicated that since hand-held chalkboards are no longer

commonly used in the school system, the distinction is no longer needed, and pizarra is now

used to refer to all chalkboards, large or small, and that perhaps for this reason the use of

encerado has declined. However, the DRAE defines encerado, with no regional

specification, as a synonym of one of the senses of pizarra, and defines tablero, also with

no regional specification, as a synonym of encerado (see section A2.4 below). Perhaps

tablero (chalkboard) was once common in Spain or in some parts of Spain, but the

evidence from this study and from the Lxico del habla culta surveys suggests that this usage

has been rare in much of Spain for many years: In the Lxico del habla culta studies

23

involving Spanish cities only 1 out of 53 respondents offered tablero in response to the

chalkboard question (Torres Martnez: 586; Salvador: 747; and Samper Padilla: 479), and

this single response came from the oldest of the studies, the Encuestas lxicas del habla

culta de Madrid, published in 1981. In the present study, tablero was not given by any of the

20 respondents, and only 6 offered encerado.

Panama & Colombia: Tablero is the dominant usage in Panama and Colombia. If in the past tablero

(chalkboard) was much more common in Spain and elsewhere than it is today, can its

survival in Panama and Colombia be characterized as an archaism

__

an archaism from a

Peninsular and General Spanish perspective

__

that has survived in these two countries? How

common was the use of tablero (chalkboard) in different parts of the Spanish-speaking

world in, say, 1900, and why has it continued to flourish in Panama and Colombia? If

tablero lost the jousting match elsewhere to pizarra and/or pizarrn, what was the cause of

its downfall?

Related concept, whiteboard: In certain settings, such as workshops and trainings (as corporate

and government training sessions are now often called), whiteboards have largely replaced

chalkboards: A whiteboard is a white plastic board used with special markers called dry

erase markers which use an ink that is easily erased from the boards surface. Research

needs to be done to determine what names are used in Spanish for whiteboards, and where.

Related to this question is the issue of which Spanish speakers refer to a whiteboard with the

same name they use for a chalkboard, perhaps adding a modifier such as blanco/a or

lquido/a

__

e.g. pizarra blanca or pizarra lquida for a whiteboard

__

and which use two

different base terms such as pizarra (blackboard) vs. tablero (whiteboard), or encerado

(blackboard) vs. pizarra (whiteboard).

A2.4 Real Academia Regional Review

DRAE grades: encerado (C), pizarra (A), pizarrn (A), tablero (C). GPA = B

DRAE definitions: encerado, (Del part. de encerar). 4. Cuadro de hule, lienzo barnizado,

madera u otra sustancia apropiada, que se usa en las escuelas para escribir o dibujar en l con clarin

o tiza y poder borrar con facilidad; pizarra, (De or. inc.). 3. Trozo de pizarra [tipo de roca]

pulimentado, de forma rectangular, usado para escribir o dibujar en l con pizarrn, yeso o lpiz

blanco. || 4. encerado (|| para escribir o dibujar en l). || 5. Placa de plstico blanco usada para

escribir o dibujar en ella con un tipo especial de rotuladores cuya tinta se borra con facilidad;

pizarrn, Am. encerado (|| para escribir o dibujar en l); tablero, 11. encerado (|| para escribir

o dibujar en l).

Comments: The DRAE defines encerado broadly as a board that can be made of hule, lienzo

barnizado, madera u otra sustancia apropiada and since slate is certainly an appropriate substance

this definition covers and subsumes sense 3 of pizarra. It is therefore unfortunate that the DRAE

divides pizarra into two separate chalkboard senses, one made specifically of slate (sense 3), and

another (sense 4) that is synonymous with encerado. In other words, its definitions unsuccessfully

try to make technical distinctions between two types of boards and two terms, pizarra and encerado,

that in fact can be synonyms. It would make more sense to cover different boards under a single

broad definition. The main bone of contention is whether whiteboards are to be included in the

concept of pizarra, pizarrn, tablero and/or encerado. Compare the following two definitions of

pizarrn, both from Mexican dictionaries: The Diccionario del espaol usual en Mxicos definition

reads Trozo de material duro y plano, generalmente de forma rectangular y de color verde, negro

o blanco, sobre cuya superficie se pueden hacer trazos con gis o con un lpiz especial y luego

24

borrarlos con un pedazo de fieltro o de tela afelpada; se usa principalmente en los salones de clase

de las escuelas: escribir sobre el pizarrn, borrar el pizarrn, pasar al pizarrn (Lara Ramos). And

the Diccionario inicial del espaol de Mxico defines pizarrn as Material duro y plano en forma

de rectngulo, de color verde o negro; sirve para escribir con gis y luego borrar: El maestro me pidi

que escribiera una idea en el pizarrn (vila).

These definitions by Mexican lexicographers have much to recommend them

__

to

internationalize the metalanguage used, all we would need to do is replace gis with tiza

__

but let us

also take a look at the American Heritage Dictionarys definition of chalkboard, in which only

the objects essential properties are included, and there is no discussion of where the object is

typically used (schools) or the materials out of which it is typically made (slate or synthetic stone):

A smooth hard panel, usually green or black, for writing on with chalk; a blackboard (Pickett).

Since a chalkboard does not stop being a chalkboard if it is not located in a school, an argument can

be made that omitting the detail of where chalkboards are typically used makes sense. On the other

hand, to give a reader who has never experienced a chalkboard more context to work with, including

this information may be useful. It largely depends on the type of reader or dictionary user the

lexicographer envisages. Similarly, it can be argued that no mention need be made of a chalkboards

composition since over the past one hundred years the materials have in fact evolved

__

most are no

longer made of slate

__

and will probably continue to evolve.

Therefore, the DRAE could also define pizarra or pizarrn succinctly as Cuadro duro, liso

y plano, por lo comn de color verde o negro, el cual est diseado para escribir o dibujar en l con

tiza and then cross-reference the regional synonyms encerado and tablero to pizarra or pizarrn.

However, if the terms pizarrn and pizarra, etc., can also refer to a whiteboard, then the definition

may need to be made more general so that it reads Cuadro duro, liso y plano, por lo comn de color

verde, negro o blanco, el cual est diseado para escribir o dibujar en l con tiza o con marcadores

especiales. In fact, a more recent English-language dictionary, the Encarta Websters College

Dictionary, published in 2005, even defines blackboard as a board of either a dark color or white

that is written on with contrasting chalk or erasable markers, used especially in classrooms

(Soukhanov). In the case of English, it remains to be seen how many native speakers would actually

refer to a board that is so patently white as a blackboard. (Yo no lo hara, pero mi propio uso tal

vez no coincide con el de la mayora.)

With regard to Spanish, another lexicographical issue is which word, pizarra or pizarrn,

should be chosen as the lead term to which all others would be cross-referenced. Pizarrn is

commonly used in more countries than pizarra and the former also has the advantage that it does

not have additional meanings (such as slate). Therefore, by selecting pizarrn as the lead term,

pizarra could then be defined (in its chalkboard sense) as pizarrn, tablero as Col. y Pan.

pizarrn, and encerado as Esp. pizarrn, whereas if pizarra is selected as the lead term, then

the cross-references would need to include a gloss such as pizarra (|| para escribir o dibujar en l)

and this requires more space.

A3 CHALKBOARD ERASER or BLACKBOARD ERASER

A3.1 Summary

Borrador is the General Spanish term. Almohadilla is common in Guatemala and Bolivia, and

perhaps in some regions (or among some speakers) of several other Spanish American countries.

Peru has a unique usage not found elsewhere.

25

A3.2 Terms by Country (3 terms plus variants)

SPAIN borrador (20/20).

MEXICO borrador (56/56).

GUATEMALA almohadilla (10/14), borrador (8/14).

EL SALVADOR borrador (16/16).

HONDURAS borrador (16/17), almohadilla (3/17).

NICARAGUA borrador (14/14).

COSTA RICA borrador (12/12).

PANAMA borrador (14/14).

CUBA borrador (17/17).

DOMIN. REP. borrador (13/13).

PUERTO RICO borrador (17/17).

VENEZUELA borrador (24/24).

COLOMBIA borrador (14/16), almohadilla (3/16).

ECUADOR borrador (14/14).

PERU mota (15/17), borrador (3/17), almohadilla (2/17).

BOLIVIA almohadilla (15/18), borrador (7/18).

PARAGUAY borrador (10/10).

URUGUAY borrador (10/10).

ARGENTINA borrador (22/22).

CHILE borrador (15/15).

A3.3 Details

General: The item tested was a standard chalkboard eraser with a felt pad, not a sponge or cushion

used to erase chalkboards. However, the image I used was not particularly clear and it is

possible that some respondents interpreted my question as referring to the latter type. The

terms borrador and almohadilla are sometimes modified by phrases such as de pizarra, de

pizarrn, de tablero or de encerado whenever speakers feel a need to be more precise since,

in an office-supply context and in some regions, borrador by itself could refer to either a

chalkboard eraser or a pencil eraser (see section A10), and an almohadilla to either a

chalkboard eraser or an ink pad (see section C2). In Peru, in contrast, mota has only one

meaning in this context and therefore needs no modifier. While it would stand to reason that

longer, specific forms such as borrador de pizarra would be more common in countries

where borrador, rather than goma (de borrar), is used in the sense of pencil eraser, research

needs to be done to determine if this is actually true. Because sponges and small cushions

are sometimes used in place of standard felt chalkboard erasers, and were no doubt used for

this purpose more so in the past, it is also possible that in regions where almohadilla is used

to erase chalkboards some speakers make a distinction between an almohadilla (cushion or

sponge used to wipe the chalkboard) and a borrador (standard chalkboard eraser with a felt

pad). It would be interesting to research the terms social stratification in different regions

and, in particular, whether in some countries the word almohadilla (chalkboard eraser

and/or cushion) is used more in rural areas and by the elderly than by younger city

dwellers. As cushions, sponges and other pads that are used to erase chalkboards become

less and less common and, even in rural areas, are replaced by standard felt chalkboard

26

erasers, this distinction between almohadilla and borrador, if one currently exists, may also

become moot. See Honduras, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru & Chile below.

Spain: To what extent do the terms cepillo, cepillo de borrar, pao and pao de borrar (chalkboard

eraser) compete with borrador in Spain? Neither cepillo nor pao is defined as a chalkboard

eraser in the DRAE, nor was either term offered by the respondents in this study, but in the

Lxico del habla culta studies dealing with usage in Madrid, Granada and Las Palmas de

Gran Canaria, cepillo and/or pao (de borrar) were offered by 9 out of 16 Madrileos, 3 out

of 25 Granadinos, and 6 out of 12 Gran Canarios (Torres Martnez: 586; Salvador: 747;

Samper Padilla: 479). Given that those studies were published in 1981, 1991 and 1998,

respectively, and the fact that none of the 20 respondents in this study offered these terms,

the following question arises: Have these Peninsular Spanish regionalisms been dying

out

__

unable to withstand the force and greater precision of General Spanish borrador, and

perhaps due to the disappearance of the old-fashioned types of chalkboard erasers

__

or are

cepillo and pao (chalkboard eraser) still alive and well in Spain, perhaps still frequently

used among Spaniards, especially of the older generations? It is true that the pool of

Spaniards who participated in my study were for the most part translators, age 40 and under,

international in outlook, and sophisticated, in short, not ones who would be likely to call a

chalkboard eraser a cepillo or a pao.

Honduras, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru & Chile: How common is almohadilla

(chalkboard eraser) in these countries, and in which of them is this usage limited to certain

provinces, states, departments, or regions? The data presented in section A3.2 above suggest

that almohadilla (chalkboard eraser) is marginal in Honduras, Colombia and Peru, and no

evidence of its use in Venezuela and Chile was encountered in this study. One Nicaraguan

stated that an almohadilla is a cloth that is moistened to wipe down chalkboards and is

distinct from a borrador, a standard chalkboard eraser. However, the DRAE indicates that

almohadilla (chalkboard eraser) is used in Nicaragua (see section A3.4 below). In addition,

the Diccionario del habla actual de Venezuela states that almohadilla is used in the Andean

region of Venezuela

4

, and defines this term as 5 And[es] Instrumento que se utiliza para

borrar el pizarrn (Nez). The Nuevo diccionario de colombianismos affirms that

almohadilla is used in the sense of chalkboard eraser in so many different departments and

regions of Colombia as to suggest that this usage is not constrained to or even typical of any

particular part of the country

5

(Haensch and Werner 1993a). And the Diccionario

ejemplificado de chilenismos y de otros usos diferenciales del espaol de Chile, published

in 1984, defines almohadilla as 2. Cojincillo para borrar la pizarra but defines borrador

as Utensilio escolar provisto de una superficie blanda o esponjosa con que se borra en la

pizarra (Morales Pettorino), which perhaps implies (depending on how one interprets the

word cojincillo) that some Chileans make or used to make this distinction between

almohadillas (pads or cushions used to erase chalkboards) and borradores (standard felt

chalkboard erasers). However, in the Lxico del habla culta de Santiago de Chile study

published in 1987, 12 out of 13 respondents offered borrador and 4 out of 13 almohadilla

in response to the chalkboard eraser question (Rabanales: 527). Therefore, if we assume that

the item used by Rabanales team in its surveys was consistently a standard chalkboard

eraser and not a sponge, cushion or pad

__

the study does not specify which item was

tested

__

then the Diccionario ejemplificado de chilenismoss claim that an almohadilla is

distinct from a borrador appears to be refuted. En fin, ya les he alargado mucho el cuento,

y basta con decir que an queda mucho por investigar.

27

A3.4 Real Academia Regional Review

DRAE grades: almohadilla (B or D?), borrador (A), mota (D).

DRAE definitions: borrador, (De borrar). 5. Utensilio que sirve para borrar lo escrito con

tiza en una pizarra o sitio semejante; almohadilla, 10. Bol., Chile, Col., Guat. y Nic. Cojn

pequeo destinado a borrar lo escrito en las pizarras de las escuelas.

Questions/Comments: If some Spanish speakers conceive of an almohadilla as a standard

chalkboard eraser with a felt pad but others as a sponge or small cushion used for the same purpose,

then the DRAE should define almohadilla as both a borrador de pizarra (or a borrador de

pizarrn) and as an esponja o pequeo cojn destinado a borrar... with the appropriate regional

specifications in each case. On the other hand, if most Spanish speakers who use the term

almohadilla do not make such a distinction, then almohadilla can just be cross-referenced to

borrador. In any case, mota needs to be defined as Per. borrador de pizarra or Per. borrador

de pizarrn.

A4 CRAYON

A4.1 Summary

Crayola is the dominant term in 8 or 9 countries, crayn in 3 or 4, and in several more both words

compete. Together crayola and crayn can perhaps be considered co-General Spanish terms as the

remaining words are commonly used in far fewer countries. Creyn is frequently heard in Cuba and

Venezuela, and the predominant usages in Spain and Chile are considerably different from those

found in the rest of the Spanish-speaking world.

A4.2 Terms by Country (c. 8 terms plus variants)

SPAIN cera (8/20), pintura (de cera) (6/20), lpiz de cera (4/20), plastidecor (3/20), color de

cera (1/20).

MEXICO crayn (33/57), crayola (32/57), color (de cera) (6/57).

GUATEMALA crayn (12/14), crayola (1/14), crayn de cera (1/14).

EL SALVADOR crayola (12/17), crayn (7/17).

HONDURAS crayola (15/20), crayn (4/20), color (2/20).

NICARAGUA crayn (10/15), crayola (6/15), lpiz de cera (1/15), lpiz de color (1/15).

COSTA RICA crayola (12/15), crayn (4/15), lpiz de color (1/15).

PANAMA crayola (6/15), crayn (6/15), lpiz de cera (5/15), creyn (3/15).

CUBA crayola (10/17), creyn (7/17), crayn (1/17).

DOMIN. REP. crayola (12/13), crayn (4/13), lpiz de cera (1/13).

PUERTO RICO crayola (17/17).

VENEZUELA creyn (16/24), creyn de cera (7/24), color (2/24).

COLOMBIA crayola (15/18), crayn (3/18), color (1/18).

ECUADOR crayola (8/15), crayn (8/15), lpiz de cera (1/15), lpiz de color (1/15).

PERU crayola (13/16), crayn (4/16).

BOLIVIA crayn (15/17), crayola (3/17), lpiz de cera (1/17), pintura (1/17).

PARAGUAY crayola (11/12), crayn (2/12), lpiz de color (1/12).

URUGUAY crayola (10/10).