Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Derrida, J - Taking A Stand For Algeria, (2003) 30 College Lit 115

Uploaded by

dekknOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Derrida, J - Taking A Stand For Algeria, (2003) 30 College Lit 115

Uploaded by

dekknCopyright:

Available Formats

Taking a Stand for Algeria

Jacques Derrida

oncerning the crisis which Algeria experiences today, only the Algerians can find political solutions. Yet these cannot be born in the isolation of the country. Everybody recognizes the complexity of the situation; diverging analyses and perspectives can legitimately be expressed about its origins and developments. Nevertheless, an agreement can be reached on a few points of principle. First of all, to reaffirm that any solution must be a civil one. The recourse to armed violence to defend or conquer power, terrorism, repression, torture and executions, murders and kidnappings, destruction, threats against the life or security of persons, these can only ruin the possibility that is still within Algerias reach in order to build its own democracy and the conditions of its economic development. It is the condemnation by all of the practices of terrorism and repression which will

Jacques Derrida was awarded the Adorno prize in 2001. Fichus came out in 2002.

Author

116

thus begin to open a space for the confrontation of each and everyones analyses, in the respect of differences. Proposals will be made to increase the number of acts of solidarity in France and elsewhere. Some initiatives are required without delay to make public opinion sensitive to the Algerian tragedy, to underscore the responsibility of governments and international financial institutions, to further the support of all for the Algerian democratic demands. I am asked to be brief, I will be.When I ask, as I will do, in the name of whom and in the name of what we speak here, I would simply like to let some questions be heard, without contesting or provoking anybody. In the name of whom and of what are we gathered here? And whom do we address? These questions are not abstract, I insist on thisand I insist that they engage first of all only me. For several reasons. Due to decency or modesty first, of course, and because of a concern about what an Appeal like ours may contain in both strengths and weaknesses. However generous or just it may be, an Appeal particularly when it resonates from here, from the walls of this Parisian auditorium, that is, for some of us, not for all precisely, but for many of us, when it is thus cast from farI always fear that such an Appeal, however legitimate and well-meaning it may be, may still contain, in its very eloquence, too much authority; and I fear that as such it also defines a place of arbitration (and there is indeed one in our Appeal, I will say something about it later). In its apparent neutrality in arbitration, such an Appeal runs the risk of containing a lesson, an implicit lesson, whether it be a lesson learnt, or worse, a lesson given. So it is better to say it, it is better not to hide it from ourselves. Above all, decency is required when one risks matching a few words to such a real tragedy about which the Appeal from the ICSAI and the League of Human Rights rightly underlines two characteristics: 1. The entanglement (the very history of the premises, of the origins and of the developments which have led to what looks like a terrifying deadlock and to the entwined sharing of responsibilities in this matter, in Algeria as well as outside); which implies that the time of the transformation and the coming of this democracy, the response to the Algerian democratic demand mentioned several times in the Appeal, this time for democracy will be long, discontinuous, difficult to gather into the act of a single decision, into a dramatic reversal which would respond to the Appeal. It would be irresponsible to believe or to make believe the opposite. This long time for democracy, we will not even be able to gather it in Algeria.Things will have to take place elsewhere too. None of the autonomy of Algerians is removed by such a serious reminder. Even if we could doubt this and even if we kept

117

College Literature 30.1 (Winter 2003)

Jacques Derrida

dreaming of such a reversal in the course of events, the very time of this meeting would be enough to remind us of it. Indeed, we are here after the so-called reconciliation talks, that is, after a failure or a simulacrum, a disaster at any rate so sadly foreseeable, if not calculated, which sketches, as if negatively, the dream of the impossible which we can neither abandon nor believe in. 2. Our Appeal also underscores the fact that faced with such an entangled situation, the diversity of perspectives and analyses is legitimate. And how true that is! But at this point, the Appeal carefully stops and goes back to what it defines as a possible agreement on a few points of principle. Yet, nobody, even among the first to sign the Appeal (I am one of them), is fooled by the fact that the diversity of analyses and perspectives, if it is taken to be legitimate, can lead some to diverge on the few points of principle at stake (for instance, about what is to be understood by the three major words or motifs of the Appeal: that of violence [all forms of violence are condemned: but what is violence, that armed violence which is the most general concept in the Appeal? Does it cover any police operation even if it claims to protect the security of citizens, and to ensureor claims to ensurethe legal and normal processes of a democratic society, etc.?], then that of civil peace [What of the civil in general? What is the civil? What does civil mean today? etc.], and above all that of the idea of democracy [Which democracy is referred to?]. In the end, these words engage only myself, for if I have supported and even participated in the preparation of the appeal for civil peace in Algeria, if I approve of all its formulations (which seem to me both prudent and demanding), I cannot be sure ahead of time that, as far as applications and consequences are concerned, my interpretation is in all respects the same as that of the others who have signed it. Thus, I will try to tell you briefly how I understand some crucial passages of the Appeal. I will do so in a dry and analytical manner, to save time but also in order to refrain from a temptation I have which some might deem sentimental: the temptation to turn a demonstration into a sensitive or pathetic testimony, and to explain how all I will say is inspired above all and after all by a painful love for Algeria, an Algeria where I was born, which I left, literally, for the first time only at nineteen, before the war of independence, an Algeria to which I have often come back and which in the end I know to have never really ceased inhabiting or bearing in my innermost, a love for Algeria to which, if not the love of citizenry, and thus the patriotic tie to a Nation-state, is nonetheless what makes it impossible to dissociate here the heart, the thinking, and the political position-takingand thus dictates all that I will say. It is precisely from this position that I ask in the name

Author

118

of what and of whom, if one is not an Algerian citizen, one joins and supports this Appeal. Keeping this question in mind, I would thus like to demonstrate telegraphically, in four points, why our Appeal cannot limit itself to a praiseworthy neutrality in front of what, indeed, must be above all the responsibility of the Algerians themselves. Hence,not to limit oneself to political neutrality, which does not mean that one has to choose a sidewe refuse this, I believebetween two sides of a front supposed to define, for a large part of the public opinion, the fundamental fact of the current conflict. On the contrary, it seems to me that political responsibility today consists not accepting this fact as natural and unchangeable. It consists of demonstrating, by saying it and by turning it into acts, that it is not so and that the democratic way has its place and its strengths and its life and its people elsewhere. By saying this is not to be politically neutral. On the contrary it means to take a stand 4 counts: To take a stand: 1. For a new international solidarity; 2. For an electoral agreement; 3. For a dissociation of the theological and the political; 4. For what I would more or less properly call a new Third Estate.

We take a stand for a new international solidarity

The Appeal says that the solutions belong to the Algerians alone, a correct claim in principle, but it adds several times that these solutions cannot be born in the isolation of the country. This reminds us of what must be made explicit in order to demonstrate the consequence: political solutions do not depend in the last instance on the citizens of this or that Nation-state. Today, with respect to what was and what remains up to a point a just imperative, that is, non-intervention and the respect of self-determination (the future of Algerian men and women of course belongs in the end to the Algerian people), of understanding it runs the risk of being, from now on, at best the rhetorical concession of a bad conscience, at worst, an alibi. Which does not mean that a right of intervention or of intrusion, granted to other states or to the citizens of other states as such, should be reinstated. That would indeed be inadmissible. But one should reaffirm the international aspect of solidarity that anchors us as citizens of determinate Nation-states. Which does complicate things, but also sets the true place of our responsibility: neither simply that of Algerian citizens, nor that of French citizens; and this is why my question, and my question as one who has signed the Appeal, comes from neither an Algerian nor a French person as such, which does not free me on the other hand of my responsibilities, civil or more than civil as a

119

College Literature 30.1 (Winter 2003)

Jacques Derrida

French citizen born in Algeria, and obliges me to do what must be done according to this logic in my country, toward the public opinion and the French government (as we try to do here; all that remains to be done in this regard has been and will still have to be set). For example (for lack of time it will be my only example) the logic of the Appeal leads us to take sidesit is indeed necessarywith respect to Algerias foreign debt and what is linked to it. This matter is also, as is well known (unemployment, despair, dramatically increasing poverty), an essential component of the civil war and all of todays sufferings. But we cannot seriously take a position on the economic recovery of Algeria without analyzing the national and international responsibilities in this situation.And, above all, without pointing to means of politico-economic interventions which go beyond Algeria, going even beyond France. It is a matter of European and worldwide stakes, and those who call, as we do, for such international endeavors and call to what the Appeal carefully names international financial institutions, those who call for these responsibilities and these solidarities, those do not speak anymore solely as Algerians or French, nor even as Europeans, even if they also and thereby speak as all of these.

We take a stand for an electoral agreement

One cannot invoke, however abstractly, democracy, or what the Appeal calls the Algerian democratic demand without taking a stand in the Algerian political sphere. A consistent democracy demands at least, in its minimal definition: 1). A schedule, that is, an electoral engagement; 2). A discussion, that is, a public discourse armed only with reasoned arguments, for example in agreement with the press; 3). A respect of the electoral decision, and thus of the possibility of transition within a democratic process which remains uninterrupted. This means that we, who have signed the Appeal, have already taken a stand twice on this matter, and it was necessary. On the one hand, against a state apparatus which urgently creates the necessary conditions, in particular those of appeasement and of discussion, in order to reinitiate as quickly as possible (and this rhythm poses today the most effective problem, the one to discuss democratically) and interrupted electoral process. Voting is not indeed the whole of democracy, but without it and without this form and this accounting of voices, there is no democracy. On the other hand, by the very reference to a democratic demand, we also take a stand against whoever would not respect the electoral decision, but would tend, directly or indirectly, before, during or after such elections, to question the very principle presiding over such plebiscite, that is, democratic life, a legal state, the respect for free speech, the rights of the minority, of political transition, of the plurality of languages,

Author

120

mores and beliefs, etc.We are resolutely opposedit is a stand we take clearly, with all of its consequencesto whoever would pretend to profit from democratic processes without respecting democracy. To say that we are logically against both of these perversions insofar as we refer to democracy in Algeria, is not to speak as either a citizen of this or that Nation-state, or as an Algerian, or as a French, or as a French from Algeria, whatever the added depth and intensity of our responsibility in this respect may be. And we are here in the international logic that has presided over the formation of the ICSAI, a committee first and foremost international. By the same token, beyond that painful Algerian example in its very singularity, we generally callas the International Parliament of Writers does in its fashion, sharing our demands and associated with us todayfor an international solidarity seeking its supports neither in the current state of international law and the institutions that represent it today, nor in the concepts of nation, state, citizenship, and sovereignty which dominate this international discourse, de jure and de facto.

We take a stand for the effective dissociation of the political and the theological

Our idea of democracy implies a separation between the state and religious powers, that is, a radical religious neutrality and a faultless tolerance which would not only set the sense of belonging to religions, cults, and thus also cultures and languages, away from the reach of any terrorwhether stemming from the state or notbut also protects the practices of faith and, in this instance, the freedom of discussion and interpretation within each religion. For example, and here first of all, in Islam whose different readings, both exegetical and political, must develop freely, and not only in Algeria. This is in fact the best response to the sometimes racist anti-Islamic movements born of that violence deemed Islamic or that would still dare to affiliate itself with Islam.

We take a stand for what I would tentatively call, to be brief, the new Third Estate in Algeria

This same democratic demand, as in fact the Appeal for civil peace, can only come, from our side as well as from those with whom we claim solidarity, from those active forces in the Algerian people who do not feel represented in the parties or structures engaged on either side of a non-democratic front. Hope can come only from these live places, these places of life, I mean, from an Algerian society which feels no more represented in a certain political state (which is also a state of fact) than in organizations that struggle against it through killing or the threat of murder, through execution in general. I say execution in general, for if we must not delude ourselves about the notion of violence, and about the fact that violence begins very early and

121

College Literature 30.1 (Winter 2003)

Jacques Derrida

spreads very far, sometimes in the least physical, the least visible, and the most legal forms of language, then our Appeal, at least as I interpret it, still positions itself unconditionally in terms of a limit to violence, i.e., the death penalty, torture, and murder.The logic of the Appeal thus requires the unflinching condemnation of the death penalty no less than of torture, of murder or the threat of murder.What I call with a more or less appropriate name the new Third Estate, is what everywhere carries our hope because it is what says no to death, to torture, to execution, and to murder. Our hope today is not only the one we share with all the friends of Algeria throughout the world. It is first and foremost borne, often in a heroic, admirable, exemplary fashion, by the Algerian man or woman who, in his or her country, has no right to speak, is killed or risks his or her life because he or SHE speaks freely, he or SHE thinks freely, he or SHE publishes freely, he or SHE associates freely. I say the Algerian man or woman, insisting, for I believe more than ever in the enlightened role, in the enlightening role which women can have; I believe in the clarity of their strength (which I hope tomorrow will be like a wave, crashing peacefully and irresistibly); I believe in the space which the women of Algeria can and must occupy in the future that we are calling for. I believe in, I have hope for their movement: irresistibly crashing in the houses and in the streets, in workplaces and in the institutions. (This civil war is for the most part a war of men. In many ways, not limited to Algeria, this civil war is also a virile war. It is thus also, laterally, in an unspoken repression, a mute war against women. It excludes women from the political field. I believe that today, not solely in Algeria, but there more acutely, more urgently than ever, reason and life, political reason, the life of reason and the reason to live are best carried by women; they are within the reach of Algerian women: in the houses and in the streets, in the workplaces and in all institutions.) The anger, the suffering, the trauma, but also the resolution of these Algerian men and womenwe have a thousand signs of them. It is necessary to see these signs, they are directed at us too, and to salute this courage with respect. Our Appeal should be made first in their name, and I believe that even before being addressed to them, it comes from these men, it comes from these women, whom we also have to hear. This is at least what I feel resonating, from the bottom of what remains Algerian in me, in my ears, my head, and my heart. Translated by Boris Belay

Note Ce texte a t prononc par Jacques Derrida lors de la runion publique qui sest tenue, linitiative du CISIA ( Comit international de soutien aux intellectuels

1

Author algriens) et de la Ligue des droits de lhomme,, au grand amphithtre de la Sorbonne le 7 fvrier 1994, la suite dun Appel pour la paix civile en Algrie. Voici deux extraits de cet Appel auxquels Derrida fait allusion dans son intervention : la crise que traverse aujourdhui lAlgrie, il appartient aux seuls Algriens dapporter des solutions politiques. Celles-ci, pourtant, ne peuvent naitre de lisolement du pays. Chacun reconnait la complexit de la situation : des analyses et des points de vue divers sexpriment lgitimement sur ses origines et ses dveloppements. Laccord peut nanmoins se faire sur quelques points de principe. Avant tout, raffirmer que toute issue ne peut tre que civile. Le recours la violence arme pour dfendre ou conqurir le pouvoir, le terrorisme, la rpression, la pratique de la torture et les excutions, les assassinats et les enlvements, les destructions, les menaces contre la vie et la scurit des personnes, ne peuvent que ruiner les possibilits dont dispose encore lAlgrie de construire sa propre dmocratie et les conditions de son dveloppement conomique. Cest la condamnation par tous des pratiques de terrorisme et de rpression qui commencera ainsi de dgager un espace pour la confrontation des analyses de chacun, dans le respect des divergences. Des propositions seront faites afin de multiplier les actions de solidarit en France et dans dautres pays. Des initiatives simposent sans retard pour sensibiliser lopinion au drame algrien, souligner la responsabilit des goouvernements et des institutions financires internationales, dvelopper le soutien de tous lexigence dmocratique algrienne. [This speech was given by Jacques Derrida at the public reunion held at the CISIA (International Committee for the Support of Algerian Intellectuals) and the League of the Rights of Man, at the Grand Amphitheater of the Sorbonne on February 7, 1994, following an Appeal for Civil Peace in Algeria. Below are two extracts from this appeal to which Derrida alludes in his speech: In the current Algerian crisis, it falls exclusively to the Algerians to develop political solutions.These, however, cannot spring from the isolation of the country. Everyone recognizes the complexity of the situation: diverse analyses and points of view legitimately reflect their origins and developments. Nevertheless, agreement may be reached on certain points: Firstly, to reaffirm that the issue is solely civil. Recourse to armed violence to defend or to conquer power, terrorism, repression, torture and execution, assassination and kidnapping, destruction, menace to life and personal security, can only ruin the potential that remains to Algeria to build her own democracy and the conditions of her economic development. It is the universal condemnation of the practice of terrorism and of repression which will thus begin to clear a space for the confrontation of individual analyses, with respect to differences.

122

123

College Literature 30.1 (Winter 2003)

Jacques Derrida

Propositions will be made to multiply the actions of solidarity in France and in other nations. Initiatives will arise without delay to sensitize opinions of the Algerian drama, to underscore the responsibility of governments and of international financial institutions to develop support for the requirements of Algerian democracy. Translated by Constance A. Regan]

You might also like

- Jewish Philosophy4Document11 pagesJewish Philosophy4dekknNo ratings yet

- Dieter Roelstraete On Renzo Martens Article - 221Document8 pagesDieter Roelstraete On Renzo Martens Article - 221dekknNo ratings yet

- Infinity As Second Person: The Transcendental Possibility of ExperienceDocument7 pagesInfinity As Second Person: The Transcendental Possibility of ExperiencedekknNo ratings yet

- 30 1crawfordDocument28 pages30 1crawforddekknNo ratings yet

- Rosenzweig and Levinas on Dialogical ThinkingDocument17 pagesRosenzweig and Levinas on Dialogical ThinkingdekknNo ratings yet

- Christoph Cox - The Subject of Nietzsche S PerspectivismDocument24 pagesChristoph Cox - The Subject of Nietzsche S PerspectivismdekknNo ratings yet

- Believe Error TheoryDocument25 pagesBelieve Error TheorydekknNo ratings yet

- Jewish PhilosophyDocument13 pagesJewish PhilosophydekknNo ratings yet

- 11 1papastephanouDocument25 pages11 1papastephanoudekknNo ratings yet

- Cursus2011 Deel3Document16 pagesCursus2011 Deel3dekknNo ratings yet

- Body-Self Van Wolputte 04Document19 pagesBody-Self Van Wolputte 04kittizzNo ratings yet

- Rond Actaeon ComplexDocument20 pagesRond Actaeon ComplexdekknNo ratings yet

- How Christian Prayer Revealed Shortcomings in Freud's View of ReligionDocument19 pagesHow Christian Prayer Revealed Shortcomings in Freud's View of ReligiondekknNo ratings yet

- Dust Celeste OlalquiagaDocument2 pagesDust Celeste OlalquiagadekknNo ratings yet

- 122 5geroulanosDocument30 pages122 5geroulanosdekknNo ratings yet

- Dust CO001Document1 pageDust CO001dekknNo ratings yet

- Identity and Event in Laruelle's PhilosophyDocument16 pagesIdentity and Event in Laruelle's PhilosophyEmre Gök0% (1)

- Friedrich Nietzsche and Graham Parkes - On MoodsDocument7 pagesFriedrich Nietzsche and Graham Parkes - On MoodsdekknNo ratings yet

- Introduction Spaces of Immigration Prevention InterdictionDocument18 pagesIntroduction Spaces of Immigration Prevention InterdictiondekknNo ratings yet

- Dworkin, Craig - A Handbook of Protocols For Literary ListeningDocument19 pagesDworkin, Craig - A Handbook of Protocols For Literary ListeningblancaacetilenoNo ratings yet

- Joan DidionDocument3 pagesJoan DidiondekknNo ratings yet

- DantoDocument17 pagesDantodekknNo ratings yet

- David Levi Strauss and Hakim BeyDocument8 pagesDavid Levi Strauss and Hakim BeydekknNo ratings yet

- The Scale of The Nation in A Shrinking WorldDocument30 pagesThe Scale of The Nation in A Shrinking WorlddekknNo ratings yet

- Beaulieu A 2011 Issue 1 2 TheStatus of Animality PP 69 88Document20 pagesBeaulieu A 2011 Issue 1 2 TheStatus of Animality PP 69 88dekknNo ratings yet

- Exploitation of Man by Man: A Beginner's Guide Nicholas VrousalisDocument19 pagesExploitation of Man by Man: A Beginner's Guide Nicholas VrousalisdekknNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary Pathos, Negation, and The Suspensive Avant-Garde John RobertsDocument15 pagesRevolutionary Pathos, Negation, and The Suspensive Avant-Garde John RobertsdekknNo ratings yet

- Shaping ThingsDocument77 pagesShaping ThingsPorrie W WatanakulchaiNo ratings yet

- Derrida, J - Response To Mulhall, (2000) 13 Ratio 415Document0 pagesDerrida, J - Response To Mulhall, (2000) 13 Ratio 415dekknNo ratings yet

- Ranciere - Is There A Deleuzian AestheticsDocument14 pagesRanciere - Is There A Deleuzian AestheticsDennis Schep100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Philippine City Approves Cockfighting OrdinanceDocument4 pagesPhilippine City Approves Cockfighting OrdinanceDenni Dominic Martinez LeponNo ratings yet

- Basilio P. Mamanteo, Et Al. v. Deputy SheriffDocument2 pagesBasilio P. Mamanteo, Et Al. v. Deputy SheriffBea BaloyoNo ratings yet

- Allan Bazar vs. Carlos A. Buizol, G.R. No. 198782. October 19, 2016Document3 pagesAllan Bazar vs. Carlos A. Buizol, G.R. No. 198782. October 19, 201612345678No ratings yet

- Doctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesDocument14 pagesDoctrine of Absorption Treason and Other CrimesEmmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciNo ratings yet

- Halaguena V PALDocument2 pagesHalaguena V PALPaul CasajeNo ratings yet

- WAIVER - For ECO PARK - Docx VER 2 5-26-17Document3 pagesWAIVER - For ECO PARK - Docx VER 2 5-26-17Jose Ignacio C CuerdoNo ratings yet

- ICC Detention Centre in The HagueDocument2 pagesICC Detention Centre in The HaguejadwongscribdNo ratings yet

- Bill of RightsDocument6 pagesBill of RightsHarshSuryavanshiNo ratings yet

- The Legal Status of Polygamy in England and Germany - A ComparisonDocument37 pagesThe Legal Status of Polygamy in England and Germany - A ComparisonThomas Al FatihNo ratings yet

- Public Administration Unit-30 Authority and ResponsibilityDocument11 pagesPublic Administration Unit-30 Authority and ResponsibilityDeepika Sharma100% (15)

- K.M., Et. Al., v. John Hickenlooper, Et. Al.: Amended ComplaintDocument45 pagesK.M., Et. Al., v. John Hickenlooper, Et. Al.: Amended ComplaintMichael_Lee_RobertsNo ratings yet

- Quimpo v. Tanodbayan, 1986Document3 pagesQuimpo v. Tanodbayan, 1986Deborah Grace ApiladoNo ratings yet

- The World's Last Divorce Debate: Does The Philippines Need A Divorce Law? by Maria Carmina OlivarDocument2 pagesThe World's Last Divorce Debate: Does The Philippines Need A Divorce Law? by Maria Carmina Olivarthecenseireport100% (1)

- EPM (Control of Noise at Construction Sites) RegulationsDocument7 pagesEPM (Control of Noise at Construction Sites) RegulationsMuhammad AliffNo ratings yet

- Moral Ascendancy Over Victim Amounts To Force RAPE AUG 16 2017Document2 pagesMoral Ascendancy Over Victim Amounts To Force RAPE AUG 16 2017Roland IntudNo ratings yet

- Ownership of A Work Created in The Course of Employment' by A Person Under A Contract of Service': Critical AnalysisDocument30 pagesOwnership of A Work Created in The Course of Employment' by A Person Under A Contract of Service': Critical AnalysisMr KkNo ratings yet

- Bar Matter No 1645Document2 pagesBar Matter No 1645abbyhwaitingNo ratings yet

- Korean Air Co., Ltd. vs. YusonDocument1 pageKorean Air Co., Ltd. vs. YusonNikki FortunoNo ratings yet

- PALEDocument2 pagesPALEMark Ian Gersalino BicodoNo ratings yet

- MTJ 03 1505Document5 pagesMTJ 03 1505The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeNo ratings yet

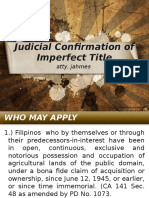

- Land Titles - Judicial Confirmation of Imperfect TItle-Orig Reg StepsDocument53 pagesLand Titles - Judicial Confirmation of Imperfect TItle-Orig Reg StepsBoy Kakak Toki86% (7)

- Consti RevDocument20 pagesConsti Revroxie_mercadoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Ethical Issues in "The Dog EaterDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Ethical Issues in "The Dog EaterEzri Mariveles Coda Jr.No ratings yet

- Panaguiton Jr. vs. DOJDocument4 pagesPanaguiton Jr. vs. DOJAngel NavarrozaNo ratings yet

- Frankie Eduardo Rendon-Zambrano, A206 037 021 (BIA May 12, 2014)Document7 pagesFrankie Eduardo Rendon-Zambrano, A206 037 021 (BIA May 12, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- In The Court of Hon'Ble Munsiff-I (P) Kozhikode O.S. No 336/2018Document4 pagesIn The Court of Hon'Ble Munsiff-I (P) Kozhikode O.S. No 336/2018Nidheesh Tp100% (2)

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 1629, Docket 96-9397Document9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 1629, Docket 96-9397Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pioneer V Todaro DigestDocument1 pagePioneer V Todaro DigestPam RamosNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice of All SubjectsDocument251 pagesMultiple Choice of All SubjectsNoel DelaNo ratings yet

- Social Exclusion PresentationDocument17 pagesSocial Exclusion PresentationPrashant S Bhosale100% (1)