Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Shipping Tech and Public Attitudes are Transforming Urban Waterfronts

Uploaded by

Mina AkhavanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Shipping Tech and Public Attitudes are Transforming Urban Waterfronts

Uploaded by

Mina AkhavanCopyright:

Available Formats

The Port-Urban Interface: An Area in Transition Author(s): Yehuda Hayuth Source: Area, Vol. 14, No. 3 (1982), pp.

219-224 Published by: The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20001825 . Accessed: 24/01/2014 07:06

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Area.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

area

1982 Volume 14 Number 3

The port-urban interface: an area in transition

Yehuda Hayuth, University of Haifa, Israel

Summary. The long-standingspatial andfunctional tiesbetween ports and citiesaregraduallyweaken ing. Technologicaldevelopmentsin ocean transportation, thegrowing public recognition of the asset of thewaterfront and emerging intermodaltransportation systemsare among themain reasonsbehind the recentchanges thathave occurred at theport-urban interface.

Ports and cities have been closely tied to one another geographically and functionally since the early history of shipping (Polanyi, 1963). Many ports and cities grew, and are still growing, on the basis of mutual benefit. The geographical proximity of cities and ports was amatter of necessity, dictated by conventional shipping technology, the nature of the trade and the size of the cities. Historically, many ports were located within an urban area, most often next to the commercial centre of the city. Many cities were situated at sites that were conducive to the establishment of a port. The port, in turn, served primarily the local area and maintained close ties with the manufactur ing industry in the city. However, as cities grew in size and ports expanded their facilities, an initial spatial and functional segregation between ports and cities emerged. The development of ' outports' in north-west Europe (Pounds, 1947) and the downstream development of ports in Britain (Bird, 1963) illustrate the trend of ports abandoning the central areas of cities. This trend has been observed, for example, in the Port of London (Bird,

1964).

In the last two decades, developments such as technological changes in the shipping industry, modernisation of port operations and increasing public concern over coastal areas, have greatly accelerated the phenomenon, loosening the spatial and functional relationship between cities and ports and subverting the traditional land-use character istics of the urban waterfront. Geographical studies which have devoted a great deal of research into land-use structure and functional districts within urban areas on the one hand (Chapin, 1965), and seaports on the other hand (Weigend, 1958; Bird, 1971), have tended, until recently, to neglect the vitally important interface between cities and ports. The land use characteristics of urban waterfronts have previously been studied in the context of metropolitan areas (Forward, 1968). Several studies have compared the waterfront land-use structure of different port cities (Forward, 1970), while others have dealt with the subject in light of coastal zone management programmes (McCalla, 1978). A study of the land-use admixture of the urban waterfront that did provide important insights into this issue was concerned not so much with maritime developments on the water front as with the contiguous area immediately behind the waterfront (Kenyon, 1968). Recent work on port-city relationships contributes significantly to the issue and pro vides case studies from various parts of the world (Hoyle and Pinder, 1981), but little has been done, so far, to analyse the port-urban interface area as a zone in transition. The purpose of this study is to examine recent changes in ocean transportation tech nology and in the attitude of the public toward shoreline areas, and to analyse their impact on the port-city interface from a spatial and functional point of view. The

219

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

220

Theport-urban interface

changes

in the waterfront area will focus on two major components: first, the spatial system, which derives from the geographical proximity of cities and ports and is re flected mainly in land-use configurations, transportation services, and functional linkages; second, the ecological system, which is concerned with air, water and aesthetic quality, as well as improving the quality of life at the port-city interface. spatial system

The

Technological changes in shipping over the last 15 years are reflected in several avenues of development (Mayer, 1973). For instance the size and draft of ships have increased enormously, rendering many ports unusable. In 1967 only 9 6% of the world's oil tankers and 1 7% of the ore and bulk carriers exceeded 50,000 tons gross. By 1979, 69. 4% of the oil tankers and 27 3% of the ore and bulk carriers were above this size (Lloyd's 1979). Since the draft of the largest oil carriers surpasses 80 and even 90 feet, very few ports around the world can presently accommodate these vessels. As a direct result, most of the maritime trade in oil, coal and ore can no longer be handled at conventional ports, because of either limited water depth or lack of sufficient back land for the storage of large quantities of cargo. Consequently, the older oil and bulk terminals are gradually disappearing from the scene of the urban waterfront, while new bulk and oil terminals are being constructed on previously undeveloped land on the outskirts of urban areas. One example that illustrates this process is the relocation of oil and bulk facilities from the Port of Marseilles to the new port of Fos nearby (Hoyle and Pinder, 1981). Still another development, with similar impact on the type and amount of cargo handled at the urban port, has been the construction of offshore terminals to accommodate very large and ultra large crude carriers (Bargaw, 1975). Technological changes in shipping are also reflected in revolutionary modifications in cargo-handling techniques. The strongest ties, both functionally and spatially, between ports and cities were in the area of the general cargo trade. The advent of containerisation, and its effect on port operations and port infrastructure, modified and weakened those ties. The land-use configuration of the waterfront is to a great extent a result of the demand imposed by the nature of the trade. The 'finger pier ' and the narrow apron bounded by the storage and transit shed-a common lay-out in the con ventional break bulk cargo handling system-is totally inadequate for the new cargo handling methods. One of the main objectives of containerisation is to improve the turn-around time of ships in ports and to increase cargo throughout. About tons of containerised cargo can be loaded and unloaded in an eight-hour 2,500-3,000 tons for general cargo that used to be common shift, compared to the 100-200 (UNCTAD, 1976). These new levels impose a high demand for new port land-use configurations, and for additional back-up space for storing and marshalling the to ten-fold more space than was needed in the break bulk system (Reid, containers-up 1975). Expansion of port facilities will be impossible if adjacent areas are built up or designated for non-port activities, or if land acquisition costs are prohibitive. Container terminals, often finding it difficult to operate at the existing waterfront port, are forced tomove out to the fringe of the urban area, where space is available, or even to relocate facilities to an entirely new location. One way in which port authorities, particularly in Europe, have solved their need for more space is via downstream reclamation, in which they have constructed wide flat sites and dredged deep water alongside in one

operation.

Perhaps one of the best examples of the effect of the relocation of cargo facilities is the rapid development of the Port of Oakland and the concomitant decline of the Port of San Francisco. The former was a small port until specialised container facilities

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Theport-urban interface

221

were constructed in the outlying areas of the city of Oakland in the early 1960s. The new site is perfectly suited to the requirements of a container port: wide berthing space, a large back-up area, and excellently accessibility to inland transportation. On the other hand, the Port of San Francisco is constrained by its old finger piers; the topography and the urban land-use structure, furthermore, prevent any major expansion. As a consequence, the port of San Francisco has lost many of its long-standing customers to its competitor across the bay. of the organisational structure of the cargo flow may also be listed Modification among key changes in transport technology. Containers, as part of the intermodal trans portation system, should ideally flow uninterruptedly from origin to destination. With the high volume of containers and the deep hinterland penetration of containerised cargo (Hayuth, 1982), an efficient interface between ocean and land transportation is essential to the operation of the port as well as to the entire transport system. No container port can maintain a high volume of traffic unless it has efficient and uncon gested access to major inland transportation networks and large market centres. In many cases, neither the land nor the access routes can be obtained in old port districts and so relocation of terminal facilities becomes unavoidable. Container trucks and trains cannot manoeuvre in the older, congested urban waterfront areas of San Francisco, the west side of Manhattan orMarseilles as easily as they can in the new large terminals of Oakland, the port of Elizabeth in New Jersey and Fos in France. The economic ties between the port and the city have suffered, too, from the adverse effect of the relocation of several traditional port functions, such as storage and ware housing, to inland locations. Congested urban waterfronts, lack of port back-up space, and the high cost of land and labour in the vicinity of seaports, on one hand, and new logistical strategies of cargo distribution (Taff, 1978), on the other hand, are the main reasons behind the establishment of inland container depots on sites located tens and even hundreds of miles from any shoreline (Hayuth, 1980). New inland terminals, such as those at Greenfield in Utah, Butte inMontana, Kano in northern Nigeria, Nei Li in Taiwan, and the container base terminal at Birmingham in England, are now performing many traditional port functions such as cargo consolidation, customs clearance, forwarding, container marshalling, packing and container repairing. The operation of container ships, or roll-on/roll-off ships, has affected also the ser vice to seamen provided at the waterfront. Seamen used to call at a port for a week or more but have now been introduced to much shorter port calls with the fast turn around time of the new ships. Only rarely will a containership remain in port for more than a day or two, and even then most of the crew must stay aboard (Evans, 1969). As a consequence, seamen's demand for such services as bars, night clubs and res taurants at the waterfront, or touring and shopping in the city, have been greatly reduced. While it is true that most urban waterfront renewal programmes have revita lised many of these services, the income generated there comes more from the city than from the port. The advent of commercial aviation virtually eliminated the service of passenger ocean liners and, consequently, reduced the port's role as a passenger terminal. Furthermore, the decentralisation of industries from metropolitan areas brought about the relocation of manufacturing plants to the outskirts of the cities (Moses and Williamson, 1967). These developments also disrupted traditional port-city relation ships and contributed tomodification of the interface area. The geographical proximity of city and port, formerly an advantage, has now become a major constraint on port development, which is striving to meet the basic demands of the new era of ocean transportation.

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

222

Theport-urban interface

The

ecological

system

Lack of awareness and interest regarding the noise, water and air pollution caused by ports long characterised the attitude of many urban communities. Moreover, the area of port-urban interaction was one of the most neglected and run-down sections of many cities. The recent and growing public concern over environmental issues and increasing citizen pressure to improve the ecological structure of cities have been responsible for many urban renewal programmes and land-use changes along urban waterfronts (Wilson, 1977). Changing public attitudes can also act as a limiting factor in the growth of a port when they conflict with port expansion needs (Pinder, 1980; Manogue, 1980). As a result, the priority use of urban waterfront land for port activities may well face criticism and challenge by various public interests. One of the institutional mechanisms reflecting the American public's changing atti tude toward shorelines in general and the urban waterfront in particular, is Section 303(b) of the Coastal Zone Management Act, passed in 1972. The CZM Act gave states the responsibility of developing coastal management programmes that would give 'full' consideration to ecological, cultural, historic, and aesthetic values, as well as the need for economic development. Port operations, clearly a water-dependent activity, have traditionally been given priority status in the allocation of urban waterfronts, but they are no longer, how ever, the only priority users in the coastal area. They must compete for waterfront space with other industrial, commercial, residential and recreational water-related users. This competition is becoming increasingly difficult for the ports for two reasons. First, the demand for space by other users is constantly growing and, as a result, the cost of land is increasing. Second, approval of port projects by various authorities, such as in the USA, the Coastal Zone Management office, Environmental Protection Agency, Fish and Wild Life Administration, and the Army Corps of Engineers, has become a long and tedious process. US port authorities must satisfy a series of require of landfill, dredging and dredged-material ments with regard to the management disposal, and air and water quality degradation (Hershman, 1978). Coastal programmes are also beginning to differentiate among various port activities, thus forcing those port facilities such as storage and warehousing, which do not have to be located on the immediate waterfront, to be relocated to inland sites. The location of shoreline activities was challenged in the 1950s when industries located on the water front were called into question over whether they made direct use of their sites and whether the location was strictly necessary for their activity (Jackson, 1955). Ports often occupy a considerable portion of the city's waterfront and diminishing public access to the shoreline has recently become a major concern (Reich and Carroll, 1980). Public access can be described as safe physical access to the waterfront or as visual access to scenic water views. Factors such as these, as well as safety and aesthetic considerations, although not always clearly defined, are often behind the re jection of requests for port expansion projects along the urban waterfront or the removal of coal, ore and oil terminals to less sensitive coastal areas. One of the most serious confrontations in this area and one with the greatest impact on the characteristics of the port-urban interface area, is the use made of obsolete port facilities on the waterfront. The space requirement for modern port operations, out growing the capabilities of city centre sites and forcing the relocation of port terminals, has left behind obsolete and unused port facilities. This coincides with the growing effort to revitalise the downtown waterfront and, as a result, a considerable change in land-use configuration, in the type of activities, and in the overall atmosphere in

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Theport-urban interface

223

many waterfront areas has occurred. For example, housing projects within the old ports are currently under construction at the ports of Amsterdam and Copenhagen. In the USA, old finger piers at the port of Seattle have been transformed into a waterfront park, public-oriented commercial enterprises and parking lots, and at 'Fisherman's in San Francisco and 'Ports of Call ' in Los Angeles attractive shops and Wharf' restaurants have replaced the former port facilities. Old wharves in Boston have become a tourist attraction, featuring an aquarium. The colonial quay in Savannah was renovated as a promenade, and an unused warehouse in the port of Philadelphia was converted into an indoor tennis centre.

Conclusions

The coexistence of seaports and port cities, a recognised necessity from the early days of shipping, is changing. New developments in ocean transportation and modern port operations have greatly accelerated the trend of spatial and functional segregation between ports and cities, mostly in the developed countries. On one hand, port auth orities must abandon obsolete facilities and relocate many of their terminals on the urban fringe. On the other hand, other commercial and recreational users have demanded and penetrated urban waterfront land. The unique traditional atmosphere of an active port waterfront devoted solely to shipping and maritime affairs is fading. The abandoned piers, deteriorated shorelines, vacant railway yards, and pitch-dark corners of the urban waterfront are being transformed. The urban shoreline is becoming more attractive and accessible to the public and better integrated into the urban

environment.

References

Bird, J. (1963) Bird, J. (1964) The major seaports of the United Kingdom 'The growth of the Port of London', (London) in Coppock J. T. and Prince H. C. (eds.) Greater

London(London) Bird, J. (1971)Seaports and seaport terminals (London)

Bragaw, K. L., Marcus, S. H., Raffaele, C. G. and Townley, R. J. (1975) The challenge of deepwater terminals

(Lexington)

Chapin, F. S. (1965) Urban land use planning (Urbana) Evans, A. A. (1969) Technical and social changes in the worlds ports (New York) Forward, N. C. (1968) 'Waterfront land use in metropolitan Vancouver, British 41 (Ottawa) Forward, N. C.

Columbia',

Geogr. Pap.

(1969) 'A comparison of waterfront land use in four Canadian ports: St. John's, Saint John, Halifax and Victoria', Econ. Geogr. 45, 155-9 Forward, N. C. (1970) 'Waterfront land use in the six Australian state capitals', Ann. Ass. Am. Geogr.

60, 517-31

Hayuth, Y. (1980) ' Inland container terminal-function and rationale ', Marit. Polic. and Manage. 7, 283-9

Hayuth, Y. (1982) 'Intermodaltransportation and the hinterlandconcept', Tijdschr. econ.soc.Geogr.73, 13-21

Hershman, M., Goodwin, R., Ruotsola, A., McCrea, M. and Hayuth, port growth and emerging coastal management programs (Seattle) Y. (1978) Under new management,

Hoyle, B. and Pinder,D. (1981)Cityport industrialization and regional development (Oxford) W. A. D. (1975)Philadelphia Jackson, waterfront industry (Philadelphia)

Kenyon, J. B. (1968) 'Land use admixture in the built-up urban waterfront: extent and implications',

Econ.Geogr.44, 152-77 Lloyd'sRegister of Shipping (1967-1979) Statist. tables (London)

H. (1980) 'Citizen groups: new and powerful participants Manogue, in urban waterfront revitalization', in Ctee. on Urban Waterfront Lands (ed.) Urban waterfront lands (Washington DC) 212-40 Mayer, H. M. (1973) 'Some geographical aspects of technological changes in maritime transportation',

Econ.Geogr.49, 145-55

Moses, L. and Williamson, H. W. (1967) 'Location of economic activities in cities', Am. Econ. Rev. 57,

211-22

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

224

Theport-urban interface

(1980) 'Community attitude as a limiting factor in port growth: the case of Rotterdam', pap. Series A, Econ. Geogr. Inst., Erasmus University Polanyi, K. (1963) ' Ports of trade in early societies', 7. Econ. Hist. 13, 30-45 Pounds, N. J. G. (1947) 'Ports and outports in north-west Europe', Geogr. J. 109, 216-28 Reich, L. and Carroll, D. (1980) 'The ports of Baltimore', in Ctee. on Urban Waterfront 53-77 (ed.) Urban waterfront lands (Washington DC)

Pinder, D.

Work.

Lands

Reid,Middleton & Associates (1975) Port system study for the portsofWashington public State andPortland, Oregon2 vols. (Edmonds) Taff, C. A. (1978) Management of physical distribution and transportation (Homewood) UNCTAD (1976) Manual of portmanagement (Geneva)

G. G. (1958) 'Some elements in the study of port geography', Weigend, Geogr. Rev. 48, 185-200 Wilson, D. (1977) ' Planning for a changing urban waterfront: the case of Toronto', Disc. Pap., 18, Dept. of Geog., Toronto

SSRC research grants

Cornwall Technical College (The College of St. Mark and St. John Foundation) 'Recent non-retirement migrants to Cornwall', B. J. H. Brown, W. T. Thorneycroft, R. W. Perry and K. G. Dean, Dept. of Geography, ?19,736 from 1 January 1982 to 31 December 1983. University of Durham 'Employment decline and the corporate sector in the U.K. sub-regions 1976-81 ', A. R. May 1982 to 30 April, 1984. Townsend, Dept. of Geography, ?22,378 from 1 University of London, Queen Mary College 'A further study of inequality inAtlanta, Georgia', D. M. Smith, Dept. of Geography, ?4,331 from 1January, 1982 to 31 December, 1982. University of Newcastle upon Tyne 'The supply of industrial premises: a planning framework', S. J. Cameron and A. A. Gillard, Dept. of Town and Country Planning, ?15,818 from 1January, 1982 to 30June, 1983. The Open University 'Property relations in the private rented sector', L. M. McDowell, Faculty of Social Sciences,

?21,344 from 1October, 1981 to 30 September, 1983.

Portsmouth Polytechnic 'The effects of community-based residential facilities on the neighbourhood-a case study of hostels for homeless single men in S.E. Hants', A. D. Burnett, Dept. of Geography, ?9,798 from 1 March, 1982 to 28 February, 1983. Queen's University, Belfast 'Protestants and social change in the Belfast area: a socio-geographical study', F. W. Boal and April, 1982 to 31March 1984. J. A. Campbell, Dept. of Geography, ?20,474 from 1 University of Glasgow 'Local participation in an integrated ruraldevelopment scheme-Ecuador', of Geography, ?3,122 from 1June, 1982 to 1June, 1983.

A. S.Morris, Dept.

University of East Anglia 'Sizewell Inquiry Review Project', T. O'Riordan, D. Hart, M. Purdue, School of Environ mental Sciences, ?21,460 from 1June, 1982 to 30 June, 1984.

This content downloaded from 193.54.110.35 on Fri, 24 Jan 2014 07:06:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- HOA 5 PPT Tanika 19040133Document24 pagesHOA 5 PPT Tanika 19040133Tanika RawatNo ratings yet

- Challenges For Urban Conservation of Core Area in Pilgrim Cities of India-1Document7 pagesChallenges For Urban Conservation of Core Area in Pilgrim Cities of India-1Sanu KadamNo ratings yet

- India Heritage Walk Series - Fort Cochin - Walkability AsiaDocument3 pagesIndia Heritage Walk Series - Fort Cochin - Walkability AsiaE.m. SoorajNo ratings yet

- Flyover: A Urban Void: Infrastructural Barrier or A Potential Opportunity For Knitting The City Fabric ?Document14 pagesFlyover: A Urban Void: Infrastructural Barrier or A Potential Opportunity For Knitting The City Fabric ?Dileep KumarNo ratings yet

- Commercial History of DhakaDocument664 pagesCommercial History of DhakaNausheen Ahmed Noba100% (1)

- Authorship and Modernity in Chandigarh: The Ghandi Bhavan and The Kiran Cinema Designed by Pierre Jeanneret and Edwin Maxwell FryDocument29 pagesAuthorship and Modernity in Chandigarh: The Ghandi Bhavan and The Kiran Cinema Designed by Pierre Jeanneret and Edwin Maxwell FryErik R GonzalezNo ratings yet

- History of Maharashtra fortsDocument14 pagesHistory of Maharashtra fortsAshish MakNo ratings yet

- Koyikkal Palace A Brief Note On The History of The BuildingDocument1 pageKoyikkal Palace A Brief Note On The History of The BuildingSriraam PNo ratings yet

- JahanpanahDocument9 pagesJahanpanahJaishree BaidNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley CivilizationDocument29 pagesIndus Valley CivilizationKritika JuyalNo ratings yet

- Perception of Urban Public Squares in IndiaDocument76 pagesPerception of Urban Public Squares in IndiaNeha MishraNo ratings yet

- Agra FortDocument35 pagesAgra Fortpankaj1617No ratings yet

- Modern Architecture CriticalDocument6 pagesModern Architecture CriticalKunj BelaniNo ratings yet

- Catal Huyuk Households and Communities in The Central Anatolian NeolithicDocument23 pagesCatal Huyuk Households and Communities in The Central Anatolian NeolithicRadus CatalinaNo ratings yet

- 1551 2144 Management Plan enDocument151 pages1551 2144 Management Plan enKhushi PatelNo ratings yet

- Urban Voids & Shared Spaces - ... Deep Within.Document5 pagesUrban Voids & Shared Spaces - ... Deep Within.Ankur BaghelNo ratings yet

- Danny CherianDocument84 pagesDanny CherianGyandeep JaiswalNo ratings yet

- 2 - Appropriate Building Technology (ABT)Document64 pages2 - Appropriate Building Technology (ABT)Yohannes Tesfaye100% (1)

- CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN AMRITSAR 2025Document158 pagesCITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN AMRITSAR 2025Nikita PurohitNo ratings yet

- Community Housing GuideDocument45 pagesCommunity Housing GuideTwinkle MaharajwalaNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Town PlanningDocument43 pagesEgyptian Town PlanningUrvashi SoinNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Tulsi BaugDocument115 pagesEvolution of Tulsi BaugDhan CNo ratings yet

- OdishaDocument68 pagesOdishaSrividhya KNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Development of Peri Urban Areas in A Developing Country A Case Study of BhubaneswarDocument6 pagesStrategies For Development of Peri Urban Areas in A Developing Country A Case Study of BhubaneswarEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- 04 Post Independence ArchitectureDocument4 pages04 Post Independence ArchitectureSonali139No ratings yet

- São Paulo CASE STUDYDocument19 pagesSão Paulo CASE STUDYOussama KhallilNo ratings yet

- YT Urban Design Case StudiesDocument59 pagesYT Urban Design Case StudiesSonsyNo ratings yet

- Muzharul Islam Archive - Fine Arts Institute, Dhaka University, BangladeshDocument2 pagesMuzharul Islam Archive - Fine Arts Institute, Dhaka University, BangladeshAditya Niloy100% (2)

- Waterfront Tourism Development GoalsDocument1 pageWaterfront Tourism Development GoalsAR Prashant Kumar100% (1)

- Mehrauli - A Heritage City, EvolutionDocument5 pagesMehrauli - A Heritage City, EvolutionDepanshu GolaNo ratings yet

- Conservation, Restoration AND Re-Adaptation: Submitted by - Devi Baruah Bid 4 Year 180473Document8 pagesConservation, Restoration AND Re-Adaptation: Submitted by - Devi Baruah Bid 4 Year 180473Srishti JainNo ratings yet

- Norman FosterDocument2 pagesNorman Fosterharry7cNo ratings yet

- DDDDDDocument99 pagesDDDDDOtterino ZiosNo ratings yet

- VMH Annual Report 2014-15 Highlights Collection, ActivitiesDocument80 pagesVMH Annual Report 2014-15 Highlights Collection, ActivitiesMaitreyee Pal100% (1)

- Portuguese Colonial ArchitectureDocument4 pagesPortuguese Colonial ArchitectureTejal BogawatNo ratings yet

- Urban Governance of Surat City S.M.C.Document17 pagesUrban Governance of Surat City S.M.C.Siddhi Vakharia100% (1)

- An Introduction To City Planning Democracy's Challenge To The American City by Benjamin Clarke MarshDocument48 pagesAn Introduction To City Planning Democracy's Challenge To The American City by Benjamin Clarke MarshAnnaNo ratings yet

- Multi-Functional Use of Public Spaces AbstractDocument7 pagesMulti-Functional Use of Public Spaces Abstractmahmuda mimiNo ratings yet

- New Towns in India - 1Document54 pagesNew Towns in India - 1Piyush GaliyawalaNo ratings yet

- Town PlaningDocument5 pagesTown PlaningMubasher ZardadNo ratings yet

- Sun Temple, Konarak, Orissa, India: Superintending ArchaeologistDocument44 pagesSun Temple, Konarak, Orissa, India: Superintending Archaeologistabirlal1975No ratings yet

- Site Plan of St. John's ChurchDocument7 pagesSite Plan of St. John's ChurchUttara RajawatNo ratings yet

- Development Plan for Bhubaneswar CityDocument56 pagesDevelopment Plan for Bhubaneswar CityDnyaneshwar GawaiNo ratings yet

- Pondicherry Master PlanDocument21 pagesPondicherry Master PlanArjun MiddhaNo ratings yet

- Profile of Study Area: Chapter - 4Document39 pagesProfile of Study Area: Chapter - 4harshitha pNo ratings yet

- Salerno Maritime TerminalDocument5 pagesSalerno Maritime TerminalJay DoshiNo ratings yet

- Urban Design Public Realm1Document34 pagesUrban Design Public Realm1dhuviNo ratings yet

- Urban Design MovementsDocument3 pagesUrban Design MovementsHarika KatariNo ratings yet

- Medieval Plannning Gulapa, CDocument13 pagesMedieval Plannning Gulapa, CCarlo GulapaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Architecture in India: An IntroductionDocument36 pagesIslamic Architecture in India: An Introductionsteve thomasNo ratings yet

- Revitalizing Mullassery Canal in KochiDocument2 pagesRevitalizing Mullassery Canal in KochiVigneshwaran AchariNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Heritage Town Pondicherry PDFDocument21 pagesEvolution of Heritage Town Pondicherry PDFAtshayaNo ratings yet

- Jut La Fatehpur SikriDocument11 pagesJut La Fatehpur SikriSharandeep SandhuNo ratings yet

- Relevance of Ceremonial Practices on Madurai's Urban MorphologyDocument39 pagesRelevance of Ceremonial Practices on Madurai's Urban MorphologyGuru Prasath ANo ratings yet

- Urban Design of ShahjahanabadDocument64 pagesUrban Design of ShahjahanabadKavitha GnanasekarNo ratings yet

- Red Fort Delhi UNESCO World Heritage SiteDocument8 pagesRed Fort Delhi UNESCO World Heritage Siteali_raza_No ratings yet

- Chandigarh's Draft Smart City ProposalDocument27 pagesChandigarh's Draft Smart City ProposalSaikhulum NarjaryNo ratings yet

- BAGHDAd The Lost CityDocument5 pagesBAGHDAd The Lost CitySiddharth MNo ratings yet

- MORE WATER LESS LAND NEW ARCHITECTURE: SEA LEVEL RISE AND THE FUTURE OF COASTAL URBANISMFrom EverandMORE WATER LESS LAND NEW ARCHITECTURE: SEA LEVEL RISE AND THE FUTURE OF COASTAL URBANISMNo ratings yet

- Accessibility 2016 CBC Chapter 11B TOCDocument16 pagesAccessibility 2016 CBC Chapter 11B TOCsteve_proughNo ratings yet

- Apache Refresh FinalDocument3 pagesApache Refresh FinalHarpreet SethiNo ratings yet

- Fire Performance of Glass-Reinforced PlasticsDocument13 pagesFire Performance of Glass-Reinforced PlasticsRobert KellyNo ratings yet

- Critical Reading - Hybrid CarsDocument3 pagesCritical Reading - Hybrid CarsManfred JimNo ratings yet

- Suzuki 150Document4 pagesSuzuki 150Betty BentonNo ratings yet

- ICC CertificateDocument13 pagesICC CertificateDanzen Bueno ImusNo ratings yet

- Ahmad Fadlillah Generator ECU Toyota PriusDocument1 pageAhmad Fadlillah Generator ECU Toyota PriusFaiz KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Rippers - Death On DartmoorDocument22 pagesRippers - Death On DartmoorИлья МарининNo ratings yet

- ArtunTorenli Thesis MAN Public 41372EB3DF63EDocument87 pagesArtunTorenli Thesis MAN Public 41372EB3DF63EAnonymous 7ZYHilDNo ratings yet

- Your TicketDocument4 pagesYour Ticketoreon desingNo ratings yet

- 2008 Greening Rail Noise MemoDocument6 pages2008 Greening Rail Noise MemoArum Choirun NisaNo ratings yet

- To What Extent Do The Incoterms 2000 Determine The Passing of Risk in A Sale Contract On Shipment Terms?Document19 pagesTo What Extent Do The Incoterms 2000 Determine The Passing of Risk in A Sale Contract On Shipment Terms?shahriar2004No ratings yet

- Batik Air Booking: Mar 7-Mar 21Document2 pagesBatik Air Booking: Mar 7-Mar 21Tanisha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Electric BrakingDocument27 pagesElectric Brakingmastanamma.YNo ratings yet

- News Releases-Sarah Del RioDocument2 pagesNews Releases-Sarah Del Rioapi-272845520No ratings yet

- Paul Klink, Administrator of The Estate of Mona McCauley Deceased v. Nancy L. Harrison, 332 F.2d 219, 3rd Cir. (1964)Document14 pagesPaul Klink, Administrator of The Estate of Mona McCauley Deceased v. Nancy L. Harrison, 332 F.2d 219, 3rd Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Guam Drivers Handbook 2Document33 pagesGuam Drivers Handbook 2Benito CanteroNo ratings yet

- Coping With Long Range FlyingDocument224 pagesCoping With Long Range Flyingjasperdejong243735100% (2)

- WB Control Loading Manual Sup ProcDocument68 pagesWB Control Loading Manual Sup ProcDian ChristaNo ratings yet

- Highway Horizontal Alignment DesignDocument76 pagesHighway Horizontal Alignment DesignUsama AliNo ratings yet

- Westmead Traffic Management CourseDocument7 pagesWestmead Traffic Management CourseHyman Jay BlancoNo ratings yet

- Pilot Radio ScriptDocument5 pagesPilot Radio ScriptViktor FelNo ratings yet

- DEED OF ABSOLUTE SALe (Motor) - JumawanDocument1 pageDEED OF ABSOLUTE SALe (Motor) - JumawanRJ BanqzNo ratings yet

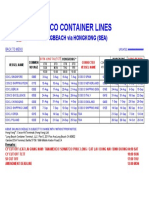

- Cosco Container Lines: Longbeach Via Hongkong (Sea)Document1 pageCosco Container Lines: Longbeach Via Hongkong (Sea)Hữu LêNo ratings yet

- Design Evaluation ReportDocument184 pagesDesign Evaluation ReportMrAgidasNo ratings yet

- GG 000 April Update 29 - 04 - 2020 WEBDocument24 pagesGG 000 April Update 29 - 04 - 2020 WEBrenandNo ratings yet

- AutoCAD ElectricalDocument2 pagesAutoCAD ElectricalGudapati PrasadNo ratings yet

- Study - Id70071 - Low Cost Carrier Market WorldwideDocument45 pagesStudy - Id70071 - Low Cost Carrier Market WorldwideAlberto Rivas CidNo ratings yet

- HZL ProjectDocument51 pagesHZL ProjectRajesh SainiNo ratings yet

- Segu 1312 EcuadorDocument17 pagesSegu 1312 EcuadorPedro PucheNo ratings yet