Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HGO Aplicaciones Clinicas Jama

Uploaded by

Priscila Tobar Alcántar0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views4 pagesAll advocate a hemoglobin a 1c level of less than 7%. Questions remain about the effect of all the oral agents and insulin on reducing macrovascular complications. Self-management training is effective in type 2 diabetes.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentAll advocate a hemoglobin a 1c level of less than 7%. Questions remain about the effect of all the oral agents and insulin on reducing macrovascular complications. Self-management training is effective in type 2 diabetes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views4 pagesHGO Aplicaciones Clinicas Jama

Uploaded by

Priscila Tobar AlcántarAll advocate a hemoglobin a 1c level of less than 7%. Questions remain about the effect of all the oral agents and insulin on reducing macrovascular complications. Self-management training is effective in type 2 diabetes.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

SCIENTIFIC REVIEW CLINICIANS CORNER

AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Oral Antihyperglycemic Therapy

for Type 2 Diabetes

Clinical Applications

Eric S. Holmboe, MD

S

EVERALCLINICALPRACTICEGUIDE-

lines for type 2 diabetes are now

available. All advocate a hemo-

globin A

1c

level of less than 7%,

and at least 1 organization has adopted

a target of 6.5%.

1-3

Despite the number

of agents tochoose from, Inzucchi

4

notes

that the only ones evaluated inrandom-

izedcontrolledtrials withregardtoclini-

cally important outcomes are insulin,

metformin, andthe sulfonylureas.

5-7

Two

important clinical trials have demon-

strated that more aggressive glycemic

control in type 2 diabetic patients re-

duced microvascular complications.

Questions remain about the effect of all

the oral agents and insulin on reducing

macrovascular complications.

6,7

Primary care physicians provide

much of the care for patients with type

2 diabetes.

8

Although this article dis-

cusses primarily drug treatment, edu-

cation on self-management, nutrition,

and exercise is essential to help pa-

tients achieve glycemic control. Self-

management training is effective in

type 2 diabetes and should be recom-

mended for all patients.

9

Recommendations for the use of oral

agents for each clinical situation are

basedonthe best evidence available and

accepted clinical guidelines. Informed

decision making about therapy, how-

ever, must involve the patient and in-

clude a clear explanationof therapeutic-

choice rationale, an assessment of his

or her understanding, preferences, and

barriers to care, and a discussion of the

risks and benefits of each therapy.

10-12

An active patient-physician partner-

ship facilitates treatment of this com-

plex, multifaceted disease.

13

The TABLE

provides a brief summary of the avail-

able oral agents and their relative costs.

The BOX provides additional re-

sources.

CLINICAL CONTEXT

Patient 1

Amoderately obese 49-year-oldwoman

(body mass index, 29 kg/m

2

) com-

plains of increased thirst, polyuria, and

fatigue. Her family history is pertinent

for diabetes in her mother and an older

brother. A random plasma glucose se-

rum test shows a level of 480 mg/dL

(26.6 mmol/L). Her serum electrolyte

and anion gap levels are normal.

At this visit, the patient meets Ameri-

canDiabetes Associationcriteria for hav-

ing diabetes.

14

Givenher symptoms and

highblood glucose level, the questionis

whether to start an oral agent or insulin

therapy. Guidelines are not prescrip-

tive regarding the choice of the initial

agent.

1-3,15

One consideration in decid-

ing whether toinitiate insulintherapy or

anoral agent is glucose toxicity.

16,17

High

Author Affiliations: Department of Medicine, Yale

University School of Medicine, NewHaven, Conn, and

Qualidigm (Connecticut Peer Review Organization),

Middletown, Conn.

Corresponding Author and Reprints: Eric S. Holm-

boe, MD, Yale Primary Care Residency Program, Wa-

terbury Hospital, 64 Robbins St, Waterbury, CT 06721

(e-mail: eholmboe@msn.comor eholmboe@wtbyhosp

.chime.org).

Scientific Review: Clinical Applications Section Editor:

Wendy Levinson, MD, Contributing Editor.

Oral agents are the mainstay of pharmacologic treatment for type 2 diabe-

tes, and physicians now have a number of agents to choose from. However,

more choices translate into more complex decision making. Many patients

with diabetes have associated comorbidities, and most diabetic patients will

require more than 1 agent to achieve good glycemic control. This article il-

lustrates several of the pharmacologic approaches to type 2 diabetes through

4 situations that use principles of evidence-based medicine. The scenarios

also highlight some of the difficulties in choosing the optimal pharmaco-

logic treatment regimen for individual patients. Physicians should also rec-

ognize that type 2 diabetes is a multisystemdisorder that requires multidis-

ciplinary care, including education and ongoing counseling for effective patient

self-management of the disease. Finally, patient preferences are a vital com-

ponent of informed decision making for pharmacologic treatment of diabetes.

JAMA. 2002;287:373-376 www.jama.com

See also pp 360 and 379.

2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, January 16, 2002Vol 287, No. 3 373

on October 10, 2007 www.jama.com Downloaded from

levels of glucose are toxic to pancreatic

beta cells, impairing insulinsecretionin

the face of relative insulindeficiency. Al-

thoughnot studiedina randomizedcon-

trolled trial, initial treatment with insu-

lin has been suggested to allow more

rapid control of plasma glucose, recov-

ery of beta cell function, and better sub-

sequent response to oral agents.

17,18

Ad-

ditionally, insulindosage canbe adjusted

quickly, facilitating more rapid control

of hyperglycemia and associated symp-

toms.

15-17

Once a stable target glucose

level has beenachieved, the patient may

be able to begin receiving an oral agent.

However, insulin therapy does require

immediate patient education on injec-

tion techniques, use of a home glucose

meter, and identification and treat-

ment of hypoglycemic reactions. If avail-

able locally, certifieddiabetes nurse edu-

cators can be particularly helpful in this

process. Deciding whether to start in-

sulin therapy also requires assessment

of the patients understanding and

wishes.

10

Whenthepatient isswitchedtoanoral

agent or an oral agent is used as initial

therapy, guidelines suggest that either

a sulfonylurea or metformin agent is

appropriate. However, given that this

patient is moderately obese, metformin

would be the recommended initial

agent.

4,7,15

It tends topromoteweight loss

andisequallyeffectiveinloweringhemo-

globin A

1c

compared with sulfonylurea

and thiazolidinedione (TZD) agents.

4

Givenher degree of hyperglycemia, this

patient mayeventuallyneed2oral agents

to achieve adequate control.

Patient 2

A 57-year-old man with type 2 diabe-

tes treated for 9 years is currently re-

ceiving glyburide at a dosage of 10

mg/d. His hemoglobin A

1c

level a week

ago was 8.5%. You suggest adding met-

formin, but the patient wonders why he

cannot increase his glyburide dose be-

cause his hemoglobin A

1c

level was al-

ways controlled well by this medica-

tion and he has been told that 10 mg is

only half the maximal dose.

Although daily doses of up to 20 mg

of glyburide and 40 mg of glipizide are

approved and can be used, data have

clearly shownthat, above 10to12mg/d,

the additional gain in glycemic control

is marginal.

19

Inaddition, the failure rate

of sulfonylurea therapy is 5%yearly, and

this patient has been receiving gly-

buride therapy for 9years.

4,6,7,15

Thus, in-

creasing his sulfonylurea dose is highly

unlikelytohelphimreachthe target level

of hemoglobin A

1c

. Likewise, switching

to another single oral agent suchas met-

formin, TZD, or meglitinide or another

nonsulfonylurea secretagogue is un-

likely to lead to adequate glycemic con-

trol, given the duration of his diabetes.

Therefore, addition of another agent

should be considered. The United

Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

(UKPDS) andother trials foundthat add-

ing metformin to sulfonylurea therapy

loweredhemoglobinA

1c

levels.

4,7,20,21

The

UKPDS, however, found an unex-

pected increase indiabetes-related mor-

tality with this combination, although

when all patients who were actually

treatedwithmetforminaccordingtopro-

tocol analysis were investigated, a 19%

reductionindiabetes-related end points

was observed.

7,22

Another optionis toadd

a TZD; this combinationhas also shown

substantial reductions inhemoglobinA

1c

levels.

4

Although no definite evidence

exists of severe hepatotoxicity withrosi-

glitazone and pioglitazone, frequent

monitoring of liver enzymes is still re-

quired because of troglitazones associa-

tion with hepatotoxicity.

Patient 3

A 55-year-old woman was diagnosed

with diabetes almost 10 years ago and is

Table. Summary of Available Oral Agents and Costs

Monthly

Retail Cost, $*

Comparative

Cost, $/d

Sulfonylureas

Micronase (glyburide), 5mg, ii bid #120 112 3-4

Diabeta (glyburide), 5 mg, ii bid #120 101 3-4

Generic glyburide, 5 mg, ii bid #120 52 2

Glynase (micronized glyburide), 6 mg, i bid #60 86 2-3

Generic micronized glyburide, 6mg, i bid #60 58 2

Glucotrol (glipizide), 10 mg, ii bid #120 111 3-4

Generic glipizide, 10 mg, ii bid #120 46 2

Glucotrol XL (glipizide GITS), 10 mg/d, ii #60 50 2

Amaryl (glimepiride), 4 mg/d, ii #60 60 2-3

Biguanides

Glucophage (metformin), 500 mg, ii bid #120 102 3-4

Glucophage XR (metformin, extended release),

500 mg/d, iiii #120

88 2-3

-Glucosidase inhibitors

Precose, 100 mg, i tid #90 78 2-3

Glyset, 50 mg, i tid #90 73 2-3

Thiazolidinediones

Avandia, 4 mg, i bid #60 175 4

Actos, 45 mg/d, i #30 169 4

Nonsulfonylurea secretagogues

Prandin (repaglinide), 2 mg, ii tid #180 165 4

Starlix (nateglinide), 120 mg, i tid #90 103 3-4

Fixed combinations

Glucovance (glyburide/metformin), 5 mg/500 mg, ii bid #120 105 3-4

Insulins (1 vial, 100 U)

Novolin or Humulin NPH 24 2

Lantus 44 2-3

Humalog 45 2-3

Humalog 75/25 46 2-3

*Cost is based on the mean of retail costs in 2001 at 3 New Haven County, Connecticut, national chain pharmacies

and is adapted from Inzucchis Yale Diabetes Center Facts and Guidelines 2001, available from Takeda Pharma-

ceuticals America; bid indicates 2 times daily; tid, 3 times daily; roman numerals, the number of tablets in each dose;

and numbers following a pound sign, the number of tablets in a months supply.

Add approximately $5 to $15 monthly for insulin syringes and alcohol wipes for 1 to 2 injections daily.

ORAL ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC THERAPY FOR TYPE 2 DIABETES

374 JAMA, January 16, 2002Vol 287, No. 3 (Reprinted) 2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on October 10, 2007 www.jama.com Downloaded from

receiving 20 mg of glipizide daily and

1000 mg of metformin twice daily. Her

hemoglobinA

1c

level is 8.5%. She is ada-

mant about not starting insulin therapy

becauseshebelieves it signals thelast step

before dying from diabetes. What are

your options?

Before embarking on a discussion

about therapy, the physicianshouldfirst

acknowledge and discuss the patients

concerns about insulintherapy. Regard-

ing drug treatment, will any of the re-

maining available oral agents lower he-

moglobin A

1c

levels in this patient?

Because of its relative decreased effi-

cacy in lowering hemoglobin A

1c

levels,

acarbose would not be a good therapeu-

tic option.

4,23

The meglitinides are insu-

lin secretagogues and therefore would

not be effective in a patient already re-

ceiving a sulfonylurea agent.

4

The only

feasible additional oral agent to use

would be rosiglitazone or pioglitazone,

both of which are approved for use in

combinationwithmetforminor a sulfo-

nylurea agent. Arecent study foundthat

43% of patients receiving triple oral

therapy (sulfonylurea, metformin, and

troglitazone) achieveda target hemoglo-

binA

1c

value (8%) comparedwithonly

6% of patients taking the metformin-

sulfonylurea combination.

24

Regardless of approach, the maingoal

for this relatively young patient re-

mains optimal glycemic control with a

hemoglobin A

1c

level below6.5%. Insu-

lin therapy is another reasonable op-

tion and is less expensive than adding

a TZD(Table).

1,4,15

If rosiglitazone or pio-

glitazone is added, the full effect of the

TZDtherapy may not be apparent for 4

to 12 weeks, but a hemoglobin A

1c

level

should be assessed at 3 months. Al-

though this patient is resistant to start-

ing insulintherapy, better glycemic con-

trol through insulin therapy in the

UKPDS

6

and the Kumomato Trial

5

led

to a reduction in microvascular compli-

cations. If the target hemoglobinA

1c

level

is not attained with the addition of a

TZD, theninsulintherapy is the best op-

tion. Many patients will eventually re-

quire insulin therapy for adequate gly-

cemic control. In the UKPDS, for

example, approximately 10% of pa-

tients initially assigned to receive a sul-

fonylurea agent hadtostart receiving in-

sulin therapy during the trial.

6

Talking

tothe patient mayhelpher overcome her

reluctance to start insulin therapy.

25

Patient 4

A72-year-old man with a history of hy-

pertension, myocardial infarction, and

New York Heart Association class II

congestive heart failure comes to the

clinic for a routine follow-up visit. At

his last visit 6 months ago, his random

blood glucose level was 180 mg/dL

(10.0 mmol/L). He was not subse-

quently tested for a fasting blood glu-

cose level but was encouraged to lose

weight and maintain a proper diet. He

now complains of having had poly-

uria and constant thirst for the past 2

months. His randombloodglucose level

is tested in your office and is 260 mg/dL

(14.4 mmol/L). His creatinine level was

1.7 mg/dL (129.63 mol/L) 6 months

ago. The patient weighs 83.3 kg. He is

receiving spironolactone, furosemide

for his hypertension, and an angioten-

sin-converting enzyme inhibitor for

congestive heart failure. What are your

therapeutic options?

Although determining a fasting glu-

cose level and a baseline hemoglobin

A

1c

level will be helpful, the patient now

has symptomatic diabetes and war-

rants pharmacologic treatment. Al-

though it appears that diet did not con-

trol his blood glucose level, reinforcing

the importance of diet and lifestyle

shouldstill be attempted.

26

Evidence ex-

ists that suggests consulting a nutri-

tionist or diabetes educator improves

glycemic control.

27,28

Regarding drug therapy, there are sev-

eral important issues to consider for this

older diabetic patient. First, what should

the target hemoglobin A

1c

level be? No

Box. Resources for Primary Care Physicians and Patients

Guidelines

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with dia-

betes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(suppl 1):S33-S43. Web site available at: http://

www.diabetes.org.

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Web site available at: http://

www.icsi.org. Printed copies can be obtained from ICSI, 800934th Ave S, Suite

1200, Bloomington, MN 55425.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Web site available at: http://

www.aace.com/clin/guides/diabetes.

All guidelines listed above are also available at: http://www.guideline.gov (Na-

tional Guideline Clearinghouse).

Organizations

American Diabetes Association, 1701 N Beauregard St, Alexandria, VA 22311.

Phone: (800) 842-6323. Information and educational brochures are available for

patients. The association has offices across the United States.

American Dietetic Association. Diabetes Care & Educational Practice Group,

216 W Jackson Blvd, Suite 800, Chicago, IL 60606. Phone: (800) 366-1655. Web

site available at: http://www.eatright.org. Good source for information about nu-

tritional therapy in diabetes.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Web site available at: http://

www.hcfa.gov. The CMS concentrates on diabetes improvement efforts for Medi-

care patients. Quality of care programs for the CMS are managed across the United

States by peer-review organizations, all of which have educational material and

ongoing projects designed to help the primary care provider care for Medicare pa-

tients with type 2 diabetes.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web site available at: http://www

.cdc.gov/nccdphp/ddt/ddthome.htm.

National Diabetes Education Program. Web site available at: http://www.ndep

.nih.gov.

ORAL ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC THERAPY FOR TYPE 2 DIABETES

2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, January 16, 2002Vol 287, No. 3 375

on October 10, 2007 www.jama.com Downloaded from

outcome data for elderly diabetics ex-

ist. However, several studies have found

that lower hemoglobin A

1c

levels are as-

sociated with lower costs for patients in

all age groups, especially those withcar-

diovascular disease,

29-31

and better con-

trol of diabetes improves the quality of

life for older diabetic patients.

32-34

Sec-

ond, what are the appropriate oral agents

for this patient?Givenhis underlyingcar-

diovascular disease, metforminwouldbe

anideal agent, but his history of conges-

tive heart failure andelevatedserumcre-

atinine levels are absolute contraindica-

tions. Remaining agents to lower blood

glucose levels are a sulfonylurea, a rapid-

acting secretagogue, or a TZD. A major

concernabout startingsulfonylureatreat-

ment in older patients is hypoglycemia

that canbe profound and prolonged be-

cause of the long half-life of the second-

generation agents. If a long-acting sul-

fonylurea is chosen, the lowest possible

starting dose (eg, 2.5 mg of glipizide)

should be initiated and the patient fully

educated about hypoglycemic reac-

tions andtreatment.

4,34

His mildrenal in-

sufficiency also places him at increased

risk for hypoglycemia. If hypoglycemia

is a major concern related to other un-

derlying health issues (eg, the patient is

at significant riskfor falls or lives alone),

a rapid-acting secretagogue taken with

meals may be safer because of its shorter

half-life.

4

The disadvantage is the fre-

quent dosing schedule required with

these agents. Acarbose couldbe tried, but

the magnitude of glucose-level reduc-

tion is less than that with other agents,

the adverse gastrointestinal effects may

bedifficult for this older patient withcon-

gestive heart failure, and again the drug

must be taken several times a day.

4

A

TZD may be prescribed but should be

usedonly cautiously inthis patient with

class II congestive heart failure. Be-

cause of their propensity to expand

plasma volume, TZDs are clearly con-

traindicatedfor patients withclass III and

IVcongestive heart failure. Therefore, for

this patient anoral agent may not be the

best treatment and in fact may increase

the risk of adverse events because of his

multiple comorbidities. Despite the mild

degree of hyperglycemia, insulinmay be

the best choice as an initial agent in this

patient. It has several advantages: flex-

ibility withregardtodose anddosing ad-

justments andmultiple preparations that

allow physicians to tailor a treatment

regimen that best meets the needs and

goals of the patient.

CONCLUSIONS

Decisions about treatment with oral

agents require a number of important

considerations, including drug efficacy

and adverse effects, strength of evi-

dence, patient preferences, cost, and ef-

fective use of nonpharmacologic thera-

pies such as diet and exercise. Patient

involvement inself-management is criti-

cal to successful glycemic control, and

all therapeutic choices must involve a

comprehensive dialogue and negotia-

tionbetweenpatient and physician. Or-

ganizations to obtain resources for car-

ing for diabetic patients are provided in

the Box. For the majority of patients, the

overarching goal is to lower the hemo-

globinA

1c

level toas close tonormal and

as safely as possible.

REFERENCES

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medi-

cal care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes

Care. 2001;24(suppl 1):S33-S43.

2. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The AACE medical guidelines for the management of

diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2000;6:1-5.

3. Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Bloom-

ington, Minn: Institute for Clinical Systems Improve-

ment; 2000. ICSI guideline GOH07.

4. Inzucchi S. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type

2 diabetes: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:360-

372.

5. Ohkubo Y, Kishikawa H, Araki E, et al. Intensive

insulin therapy prevents the progression of diabetic

microvascular complications in Japanese patients with

non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res

Clin Pract. 1995;28:103-117.

6. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive

blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin

comparedwithconventional treatment andrisk of com-

plications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33).

Lancet. 1998;352:837-853.

7. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of in-

tensive blood-glucose control with metformin on com-

plications in overweight patients with type 2 diabe-

tes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352:854-865.

8. Griffin S, Kinmonth AL. Systems for routine sur-

veillance for people with diabetes mellitus [Cochrane

Reviewon CD-ROM]. Oxford, England: Cochrane Li-

brary, Update Software; 2000;issue 4.

9. Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Venkat Narayan KMV.

Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2

diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:561-587.

10. Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, et al.

Informeddecisionmakinginoutpatient practice. JAMA.

1999;282:2313-2320.

11. Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ, for the Evidence-

Based Medicine Working Group. Users guides to the

medical literature, II: how to use an article about

therapy or prevention, B: what were the results and

will they help me in caring for my patients? JAMA.

1994;271:59-63.

12. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do

patients wish to play in treatment decision making?

Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1414-1420.

13. Wagner EH, Davis C, Schaefer J, et al. A survey

of leading chronic disease management programs.

Managed Care Q. 1999;7:56-66.

14. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classi-

ficationof Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Com-

mittee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabe-

tes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(suppl):S5-S20.

15. DeFronzo RA. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2

diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:281-303.

16. Yki-Jarvinen H. Acute and chronic effects of hy-

perglycaemia on glucose metabolism. Diabet Med.

1997;14(suppl 3):S32-S37.

17. Rossetti L, Giaccari A, DeFronzo RA. Glucose tox-

icity. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:610-630.

18. Kayashima T, Yamaguchi K, Konno Y, Nani-

matsu H, Aragaki S, Shichiri M. Effects of early intro-

ductionof intensive insulintherapy onthe clinical course

in non-obese NIDDMpatients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract.

1995;28:119-125.

19. Stenman S, Melander A, Groop PH, Groop LC.

What is the benefit of increasing the sulfonylurea dose?

Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:169-172.

20. Hermann LS. Therapeutic comparison of metfor-

min and sulfonylurea, alone and in various combina-

tions. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1100-1109.

21. Erle G, Lovise S, Stocchiero C, et al. A compari-

son of preconstituted, fixed combinations of low-

dose glyburide plus metformin versus high-dose gly-

buride alone in the treatment of type 2 diabetic

patients. Acta Diabetol. 1999;36:61-65.

22. Palumbo PJ. Editorial. Endocr Pract. 1998;4:428-

429.

23. Scheen AJ. Clinical efficacy of acarbose in diabe-

tes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 1998;24:311-320.

24. Yale J-F, Valiquett TR, Ghazzi MN, et al. The effect

of a thiazolidinedione drug, troglitazone, on glyce-

mia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus poorly

controlled with sulfonylurea and metformin. Ann In-

tern Med. 2001;134:737-745.

25. Snoek FJ. Barriers to good glycemic control. Int J

Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(suppl):S12-S20.

26. Maazuca SA, Moorman NH, Wheeler ML, et al.

The diabetes education study. Diabetes Care. 1986;

9:1-10.

27. Peyrot M, Rubin RR. Modeling the effects of dia-

betes education on glycemic control. Diabetes Educ.

1994;20:143-148.

28. Franz MJ, Monk A, Barry B, et al. Effectiveness

of medical nutrition therapy provided by dietitians in

the management of non-insulin diabetes mellitus.

J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:1009-1017.

29. Gilmer TP, OConnor PJ, Manning WG, Rush WA.

The cost to health plans of poor glycemic control. Dia-

betes Care. 1997;20:1847-1853.

30. Wagner EH, Sandhu N, Newton KM, et al. Ef-

fects of glycemic control on healthcare costs and uti-

lization. JAMA. 2001;285:182-189.

31. Testa MA, Simonson DC. Health economic ben-

efits and quality of life during improved glycemic con-

trol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA.

1998;280:1490-1496.

32. Wandell PE, Tovi J. The quality of life of elderly

diabetics. J Diabetes Complications. 2000;14:25-30.

33. Goddijn PP, Bilo HJ, Feskens EJ, et al. Longitudi-

nal study on glycemic control and quality of life in pa-

tients with type 2 diabetes mellitus referred for inten-

sive control. Diabet Med. 1999;16:23-30.

34. Jennings PE. Oral antihyperglycaemics: consid-

erati ons i n ol der pati ents wi th non-i nsul i n-

dependent diabetes mellitus. Drugs Aging. 1997;10:

323-331.

ORAL ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC THERAPY FOR TYPE 2 DIABETES

376 JAMA, January 16, 2002Vol 287, No. 3 (Reprinted) 2002 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

on October 10, 2007 www.jama.com Downloaded from

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Predominantly Plant-Based Pregnancy GuideDocument179 pagesThe Predominantly Plant-Based Pregnancy GuidePriscila Tobar Alcántar100% (1)

- Hiper Hipoparatir NejmDocument13 pagesHiper Hipoparatir NejmPriscila Tobar AlcántarNo ratings yet

- Ajuste de Dosis de Medicamentos en Paciente RenalDocument46 pagesAjuste de Dosis de Medicamentos en Paciente RenalThelma Cantillo RochaNo ratings yet

- La Teta Cansada - Montserrat Reverte PDFDocument4 pagesLa Teta Cansada - Montserrat Reverte PDFIpNo ratings yet

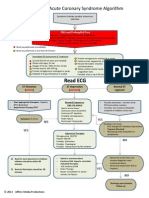

- ACS Algorithm DiagramDocument1 pageACS Algorithm DiagramPriscila Tobar Alcántar100% (1)

- Diabetic KetoacidosisDocument16 pagesDiabetic Ketoacidosisdrtpk100% (2)

- Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol on GalactogoguesDocument8 pagesBreastfeeding Medicine Protocol on GalactogoguespaulinaovNo ratings yet

- MayoClinProc Anemia in Adults A Contemporary Approach To DiagnosisDocument7 pagesMayoClinProc Anemia in Adults A Contemporary Approach To DiagnosisBarbarita Alvarado CamposNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults ManagementDocument16 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults ManagementPriscila Tobar AlcántarNo ratings yet

- Myxedema AscitesDocument4 pagesMyxedema AscitesPriscila Tobar AlcántarNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in AdultsDocument20 pagesAcute Appendicitis in AdultsPriscila Tobar AlcántarNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HCC GuidebookDocument153 pagesHCC Guidebookleadmonkeyboy100% (2)

- Deteksi Dini Kegawatdaruratan Maternal Dan Neonatal (RS Persada Medika Cikampek) PEBDocument10 pagesDeteksi Dini Kegawatdaruratan Maternal Dan Neonatal (RS Persada Medika Cikampek) PEBindra pradjaNo ratings yet

- Magic Wave July 2011 PDF 69Document19 pagesMagic Wave July 2011 PDF 69Budi TurmokoNo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan LKDFNDDocument3 pagesMarketing Plan LKDFNDapi-392259592No ratings yet

- Nutrition ManualDocument405 pagesNutrition ManualRaghavendra Prasad100% (1)

- Acanthosis NigricansDocument32 pagesAcanthosis NigricansZeliha TürksavulNo ratings yet

- Anatomia SufletuluiDocument1 pageAnatomia SufletuluiAlexandrina DeaşNo ratings yet

- Genetically Engineered Insulin and Its Pharmaceutical AnaloguesDocument11 pagesGenetically Engineered Insulin and Its Pharmaceutical AnaloguesNatália ZeninNo ratings yet

- DR Sibli PDFDocument19 pagesDR Sibli PDFIva Dewi Permata PhilyNo ratings yet

- Diabetes and Stroke RisksDocument26 pagesDiabetes and Stroke RisksPrecious SantayanaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder DystociaDocument13 pagesShoulder Dystociarolla_hiraNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors for PeriodontitisDocument174 pagesRisk Factors for PeriodontitisdevikaNo ratings yet

- National Geographic March 2016Document148 pagesNational Geographic March 2016Anonymous Azxx3Kp9No ratings yet

- Step 1 UworldDocument25 pagesStep 1 UworldKarl Abiaad100% (23)

- Dietary Management of Indian Vegetarian Diabetics: M. Viswanathan and V. MohanDocument2 pagesDietary Management of Indian Vegetarian Diabetics: M. Viswanathan and V. Mohanrockingtwo07No ratings yet

- Hemo Glucose TestDocument3 pagesHemo Glucose TestrocheNo ratings yet

- FIT UK Recommendations For Injection TechniqueDocument48 pagesFIT UK Recommendations For Injection TechniqueMadeleine OchianuNo ratings yet

- The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) : Clinical and Therapeutic Implications For Type 2 DiabetesDocument6 pagesThe UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) : Clinical and Therapeutic Implications For Type 2 DiabetesLaila KurniaNo ratings yet

- AAHA Diabetes Guidelines - FinalDocument21 pagesAAHA Diabetes Guidelines - FinalKátia SouzaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Carrot JuiceDocument0 pagesBenefits of Carrot JuiceeQualizerNo ratings yet

- Natural Medicines Used in The Traditional Chinese Medical System For Therapy of Diabetes MellitusDocument21 pagesNatural Medicines Used in The Traditional Chinese Medical System For Therapy of Diabetes MellitusparibashaiNo ratings yet

- International Nursing Conference Abstracts - AINEC 2018Document42 pagesInternational Nursing Conference Abstracts - AINEC 2018Rika Fatmadona100% (1)

- Insulin Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes UpdateDocument83 pagesInsulin Therapy in Type 1 Diabetes UpdateasupicuNo ratings yet

- Diabetic NephropathyDocument7 pagesDiabetic NephropathyPlot BUnniesNo ratings yet

- Form 4 - Graphic Stimuli and Short TextsDocument3 pagesForm 4 - Graphic Stimuli and Short TextsRupert Quentin William Kingston PNo ratings yet

- Change Management in ActionDocument28 pagesChange Management in Actionsikkim blossomsNo ratings yet

- Interactive Patient Case Management #1Document33 pagesInteractive Patient Case Management #1Luzman HizrianNo ratings yet

- 2015 March 11 Peanut ReviewDocument28 pages2015 March 11 Peanut ReviewEmmanuel AbonNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Tests To Evaluate Fluid StatusDocument52 pagesLaboratory Tests To Evaluate Fluid StatusLester Exconde Alfonso0% (1)

- Katie Humphrey-Freedom From PCOS-lulu - Com (2010)Document131 pagesKatie Humphrey-Freedom From PCOS-lulu - Com (2010)Patricia ReynosoNo ratings yet