Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Isolation

Uploaded by

Santiago TuestaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Isolation

Uploaded by

Santiago TuestaCopyright:

Available Formats

Isolation, an Ancient and Lonely Practice, Endures

By ABIGAIL ZUGER, M.D. Published: August 30, 2010

TWITTER LINKEDIN SIGN IN TO E-MAIL PRINT

REPRINTS

SHARE

Historically speaking, people with the bad luck to develop an infection have never had it so good. Modern medicine can deploy a vast array of antibiotics and other tools for their benefit.

Enlarge This Image

Joanna Szachowska

For some of them, though, our shiny, state-of-the-art treatment includes a direct carryover from the Middle Ages. These are the people who are not just infected on the inside but also infested on the outside, covered with germs. And when they are hospitalized we hustle them into an isolation room, and no matter how much they may protest and complain, and no

matter how cumbersome it makes the rest of their medical care, we never let them out. Isolation must be one of the oldest medical tools, and in some ways it is one of the most brutal. Purists routinely point out that no one has ever definitively proved that it accomplishes its goals any better than, say, assiduous hand washing and the enthusiastic use of bleach. But isolation is probably too primal and entrenched a practice ever to be studied in the usual dispassionate way. We have at least improved a little on standard 14th-century medical practice by understanding more about how germs behave. So we keep patients with active tuberculosis in rooms specially ventilated, so that in theory, germs do not rush out into the public corridor when the door is opened. All visitors wear tight-fitting masks, but gloves and gowns are unnecessary, as TB does not spread by touch. Touch does, however, transmit methicillin-resistant staph, or MRSA, and the other antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are the bane of many hospitals these days. In ours, some of the isolation rooms go to people harboring these germs, but most now are occupied by patients with the intestinal infection called C. difficile colitis. This organism is a spore-former: it makes small, hard seeds that cling to surfaces and parachute all over the place. Patients are, to use the unusually evocative technical terms, covered with a fecal veneer and they move in a fecal cloud. A microscopic version of Google Earth, scanning them in and out, would show a small, malevolent universe consisting of a human being surrounded by a shimmering, human-shaped cloud of bacteria. When patients turn in bed, giant waves of bacteria rise and travel on air currents all over the room, landing on bedside tables, on adjacent beds and on the people in those beds. The palms of people who touch these patients turn gritty with bacteria, and every time those caring hands touch another patient, the bacteria stick fast. Our hospitals current policy for avoiding the resulting outbreaks of infection is typical of most: every patient with diarrhea is isolated until we have proven C. difficile is not causing the problem. Each goes into a private room, with boxes of disposable gloves and gowns by the door, which remains closed. These gowns are thick yellow paper smocks individually wrapped in plastic, with cotton-knit cuffs and ties that wrap around the waist. The gloves are standard-issue vinyl, packed into boxes of S, M and L. Putting on the gloves and gowns takes a

couple of minutes (unless the supplies are missing or we are down to the ridiculously tiny size S gloves, in which case the search for replacements can go on quite a while). Then you have to take it all off again: the gown is untied and peeled over the gloves, which go off last, optimally sequestered in a bundle of contaminated surfaces all facing inward. The bundle must be stuffed into the red can of contaminated garbage, which is invariably full. Then the hands are washed (with soap and water, as clostridial spores laugh at alcohol-based cleansers). Then it is on to the next patient and, often, the same ritual. Isolation is an immense nuisance for everyone. For a nurse rushing in and out of patients rooms dozens of times a day, all that dressing and undressing is just not possible. Nurses learn to change their routines to get everything done in fewer visits. Meanwhile, patients with diarrhea need a lot of nursing care. They may begin to complain they are getting very short shrift in that department and, come to think of it, are not seeing the doctors much either. These patients feel terrible anyway, and they feel even worse feeling terrible all alone. Any intimation that isolated patients are at risk of substandard medical care will elicit passionate denials from all individuals and institutions involved. But some data argue otherwise. Researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that doctors and nurses alike visit the isolated less often. One study found that isolated patients had six times the usual rates of hospital-associated complications like pressure sores and falls. Some isolated patients say they enjoy the privacy, but most complain of feeling lonely and stigmatized. On one survey, isolated patients consistently responded less enthusiastically than others to nearly every question about their hospital experience (although they did not complain enough to make a statistical difference). On the surface, after all, all sick people are pretty much the same: disheveled, unhappy men and women lying in bed, wishing they were somewhere else. For centuries, the doctors challenge has been to see the individual patient lying within the cloud of illness.

But for isolated patients, the challenge has become just the reverse: the doctor must turn away from the individual and minister primarily to that invisible, evanescent cloud. It is hard to say which is the more difficult. A fragile old woman was admitted to our hospital not long ago, sick and confused, a few specks of raspberry lipstick still clinging bravely to her lower lip. During the day, propped up in a chair in the corridor, she seemed to take pleasure in the frantic comings and goings of the ward. At night, she cried inconsolably. After a few days she developed a bad case of diarrhea. The nurses moving, it seemed, more slowly than usual arranged her and her belongings on her bed and wheeled it toward an isolation room. You could hear her sobbing all the way down the hall, even after the door closed behind her. Those of us not involved in her care never saw her again, but when we passed by her room we often heard those muffled sobs until she died a few weeks later. Increasingly, modern medicine forces us to specialize in the invisible. Here we had invisible germs with an inviolable mandate, and an all too visible patient pleading with us to ignore it. It was quite a struggle to try to see the one, to try not to see the other. Dr. Abigail Zuger, who writes the monthly Books column, is an infectious-disease physician in Manhattan.

You might also like

- Productflyer - 978 0 387 95167 6Document1 pageProductflyer - 978 0 387 95167 6Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 8Document11 pagesLec 8Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 9Document11 pagesLec 9Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 9Document11 pagesLec 9Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec1 1Document17 pagesLec1 1Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 8Document11 pagesLec 8Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Metal Casting Moulding Sands and Processes ExplainedDocument9 pagesMetal Casting Moulding Sands and Processes ExplainedSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 7Document10 pagesLec 7Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 7Document10 pagesLec 7Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 8Document11 pagesLec 8Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec1 2Document12 pagesLec1 2Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Technical Textiles IntroductionDocument17 pagesTechnical Textiles IntroductionSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 7Document10 pagesLec 7Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 5Document10 pagesLec 5Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 9Document11 pagesLec 9Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Links LaboDocument1 pageLinks LaboSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- UniPrep - D - 315 - LL - (DS) Doc (SWA122382a8c343c)Document5 pagesUniPrep - D - 315 - LL - (DS) Doc (SWA122382a8c343c)Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Lec 29Document28 pagesLec 29Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- UniClean - 501 - (DS) Doc (SWA191802a863fa3)Document5 pagesUniClean - 501 - (DS) Doc (SWA191802a863fa3)Santiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Zylite HT Plus: Hot Acid Zinc ElectrolyteDocument20 pagesZylite HT Plus: Hot Acid Zinc ElectrolyteSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Sealer 300 W Family: Clear Reactive Inorganic SealersDocument2 pagesSealer 300 W Family: Clear Reactive Inorganic SealersSantiago Tuesta100% (2)

- Challenges of Applying Diamond-Like Carbon Coatings to Large Areas of Decorative GlassDocument4 pagesChallenges of Applying Diamond-Like Carbon Coatings to Large Areas of Decorative GlassSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Zylite HT Plus: Hot Acid Zinc ElectrolyteDocument20 pagesZylite HT Plus: Hot Acid Zinc ElectrolyteSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Sealer 300 W Family: Clear Reactive Inorganic SealersDocument2 pagesSealer 300 W Family: Clear Reactive Inorganic SealersSantiago Tuesta100% (2)

- Cen-Puc, M. - A Dedicated Electric Oven For Characterization of Thermoresistive PolymernanocompositDocument10 pagesCen-Puc, M. - A Dedicated Electric Oven For Characterization of Thermoresistive PolymernanocompositSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

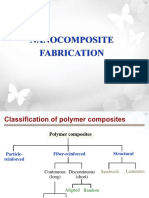

- II Nanocomposite FabricationDocument46 pagesII Nanocomposite FabricationSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Nixon, J. - Understanding The Behaviour of PET in Stretch Blow MouldingDocument11 pagesNixon, J. - Understanding The Behaviour of PET in Stretch Blow MouldingSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- Sealer Technology: Corrosion Resistant CoatingsDocument8 pagesSealer Technology: Corrosion Resistant CoatingsSantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

- III NanoclayDocument40 pagesIII NanoclaySantiago TuestaNo ratings yet

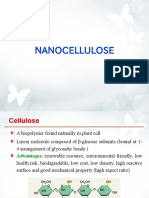

- V NanocelluloseDocument38 pagesV NanocelluloseSantiago Tuesta100% (3)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- USA FamulaturDocument3 pagesUSA FamulaturPianistinbeaNo ratings yet

- List of English Speaking Doctors in BerlinDocument19 pagesList of English Speaking Doctors in BerlinAnggêr JamungNo ratings yet

- UAB Hospital Parking Options and MapDocument2 pagesUAB Hospital Parking Options and MapUAB MedicineNo ratings yet

- ANA Nursing Sensitive Indicator PDFDocument29 pagesANA Nursing Sensitive Indicator PDFAchmad Hidayatullah HafidNo ratings yet

- Reggie Bert R. Sintos B.S. Architecture 4-A Eastern Visayas State UniversityDocument1 pageReggie Bert R. Sintos B.S. Architecture 4-A Eastern Visayas State UniversityRoberto R. SintosNo ratings yet

- Major Challenges in The Health Sector in BangladeshDocument13 pagesMajor Challenges in The Health Sector in Bangladesh12-057 MOHAMMAD MUSHFIQUR RAHMANNo ratings yet

- OPT B1 U05 Grammar HigherDocument1 pageOPT B1 U05 Grammar HigherdadadadNo ratings yet

- Challan Form 32Document66 pagesChallan Form 32Muhammad Farhan SaleemiNo ratings yet

- The Adyar Cancer InstituteDocument3 pagesThe Adyar Cancer InstituteSafetybossNo ratings yet

- University Grants CommissionDocument25 pagesUniversity Grants CommissionAvijit DebnathNo ratings yet

- Federal Medical CentreDocument16 pagesFederal Medical CentreJidda MohammedNo ratings yet

- Maternity Admission Forms: Congratulations and Thank You For Choosing To Give Birth To Your Baby at The BaysDocument9 pagesMaternity Admission Forms: Congratulations and Thank You For Choosing To Give Birth To Your Baby at The BaysraraNo ratings yet

- Nursing ExamDocument11 pagesNursing ExamKaren Mae Santiago Alcantara50% (2)

- Introduction:-: Ambulatory Healthcare Organizations IntroducedDocument7 pagesIntroduction:-: Ambulatory Healthcare Organizations Introducedanimesh pandaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Protection Rights of Consumers Can by DRDocument16 pagesConsumer Protection Rights of Consumers Can by DRLAW MANTRANo ratings yet

- Nur 862 Clinical Competencies PortfolioDocument11 pagesNur 862 Clinical Competencies Portfolioapi-457407182No ratings yet

- Tata AIG Medi Care 82932b277aDocument30 pagesTata AIG Medi Care 82932b277aChandra SekaranNo ratings yet

- Member Guide: Enhanced Sahtak PlanDocument35 pagesMember Guide: Enhanced Sahtak PlanmaniiscribdNo ratings yet

- Seeing The Person in The Patient The Point of Care Review Paper Goodrich Cornwell Kings Fund December 2008 0Document76 pagesSeeing The Person in The Patient The Point of Care Review Paper Goodrich Cornwell Kings Fund December 2008 0Levina Benita100% (1)

- August 5, 2016 Strathmore TimesDocument24 pagesAugust 5, 2016 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Amended Rules On EmployeesDocument21 pagesAmended Rules On EmployeeslchieSNo ratings yet

- Outline 2006-07Document196 pagesOutline 2006-07Manish BokdiaNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Clinical Nursing Skills and Techniques 8th Edition Perry Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Clinical Nursing Skills and Techniques 8th Edition Perry Test Bank PDFmespriseringdovelc70s100% (9)

- History of Psycho-Oncology - Holland 2010Document10 pagesHistory of Psycho-Oncology - Holland 2010Silvia Katheryne CabreraNo ratings yet

- Medico Valley Foundation IndiaDocument3 pagesMedico Valley Foundation IndiaMedico Valley100% (1)

- Model of CareDocument12 pagesModel of CareyanzainudinNo ratings yet

- A Healthy ImageDocument6 pagesA Healthy Imagedwi yolla OkhesiaNo ratings yet

- Pennsylvania Health Care PerformanceDocument7 pagesPennsylvania Health Care PerformanceWHYY NewsNo ratings yet

- 1 Anju Bio DataDocument3 pages1 Anju Bio DataAnju BijoNo ratings yet

- Patient Flow at Brigham and Women's Hospital Written CaseDocument5 pagesPatient Flow at Brigham and Women's Hospital Written CaseAlimKassymovNo ratings yet