Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thinking The Apocalypse: A Letter From Maurice Blanchot To Catherine David

Uploaded by

Tolle_LegeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Thinking The Apocalypse: A Letter From Maurice Blanchot To Catherine David

Uploaded by

Tolle_LegeCopyright:

Available Formats

C r i t i c a l I n q u i r y , V o l . 1 5 , N o . 2 . ( Wi n t e r , 1 9 8 9 ) , p p . 4 7 5 4 8 0 .

476

Maurice Blanchot

Thinking the Apocalypse

an end already foretold by Nietzsche, who was still part of it, however. And yet it is undeniable that by joining the National Socialists Heidegger returned to ideology and, what is even more disconcerting, did so unawares. Each time he was asked to recognize his "error," he kept a stony silence or expressed himself in such a way that he aggravated his situation (for a Heidegger could not be mistaken: it was the Nazi movement that had changed by abandoning its radicalism). However, Lacoue-Labarthe reminds us (I was not aware of it) that in private Heidegger, referring specifically to his political involvement of 1933 to 1934, admitted that he had committed "the greatest blunder of my life" ("blunder," nothing more).* Now, since 1986, we have known, by way of an account by Karl Lowith, that in 1936 (two years after resigning from his post as rector), he was affirming his same faith in Hitler, the same certainty that "National Socialism was the proper path for ~ e r m a n ~It ." ~ would be worthwhile to quote this overwhelming account, the words of a man whose intellectual and moral probity are unquestionable (and who, moreover, was Heidegger's disciple or, to be more precise, his student and close associate who had often taken care of Heidegger's children). While Heidegger was in Rome to give his lecture on Holderlin, Lowith, who was living there as a refugee in miserable lodgings with almost no books (which moved Heideggerno, Heidegger was not a book-burner, as Farias suggests), took advantage of a walk to question him on the burning topic that up until then everyone had avoided. I quote: I steered the topic to the controversy over the Neue Ziircher Zeitung and told him that I did not agree either with the way in which Karl Barth was attacking him or in the way Staiger was deferiding him, because my opinion was that his taking the side of National

2. To be fair, or to try to be, we must take into account the few reservations Heidegger used (all the while concealing them) to diminish the glorification of National Socialism. As I wrote a long time ago in L ~ n t r e t i e ninfini (Paris, 1969), it is undeniable that the course on Nietzsche given during the triumph of National Socialism constitutes an increasingly aggressive criticism of the crude way in which the "official philosophy" claimed to utilize Nietzsche. 3. Karl Lowith, Mein Leben in Deutschland vor und nach 1933: ein Bericht (Stuttgart, 1986), p. 57. Lowith's essay on Heidegger and Husserl, entitled "Mein letzes Wiedersehen mit Husserl in Freiburg in 1933 und mit Heidegger in Rom 1936" (hereafter abbreviated "M"), was written in 1940 as a personal record with no intention for publication. Its tardy publication in 1986 was the result of a decision by Mrs. Ada Lowith.

Maurice Blanchot, one of France's preeminent writers, has written, among many other books, The Last Man, Death Sentence, The Madness of the Day, and The Gaze o f Orpheus and Other Literary Essays. Paula Wissing, a free-lance translator and editor, has recently translated Paul Veyne's Did the Greeks Believe in Their Myth?

Critical Inquiry

Winter 1989

477

Socialism was in agreement with the essence of his philosophy [my emphasis]. Heidegger told me unreservedly that I was right and developed his idea by saying that his concept of historicityGeschichtlichkeit-was the foundation for his political involvement. ["M," p. 571 I interrupt here to stress that Heidegger, then, was accepting the statement that there is a philosophy of Heidegger, which confirms Lacoue-Labarthe's intuition that political involvement was what transformed this thought into philosophy. But the reservations and doubts of this "philosopher," as he expressed them at the time to Lowith, are nothing but mediocre political opinions. T o continue: "Only, he had underestimated two things: the vitality of the Christian churches and the obstacles that the Anschluss would encounter. Which led him to conclude, moreover, that this was excessive organization [he means the administrative structure, I suppose] created at the expense of vital forces" ("M," p. 57). Lowith adds this commentary: The destructive radicalism of the whole movement and the petitbourgeois character of all organizations of the "Strength through Joy" type never occurred to him, for Heidegger himself was a petit-bourgeois radical. In response to my remark that I understood many things about his attitude, with one exception, which was that he would permit himself to be seated at the same table with a figure such as Julius Streicher (at the German Academy of Law), he was silent at first. At last he uttered this well-known rationalization (which Karl Barth saw so clearly), which amounted to saying that "it all would have been much worse if some men of knowledge [which was how he termed himself] had not been involved." And with a bitter resentment toward people of culture (Gebildete), he concluded his statement: "If these gentlemen had not considered themselves too refined to become involved, things would have been different, but I had to stay in there alone." T o my reply that one did not have to be very refined to refuse to work with a Streicher, he answered that it was useless to discuss Streicher; the Stiirmer was nothing more than "pornography." Why didn't Hitler get rid of this sinister individual? He couldn't understand it. Perhaps Hitler was afraid of him. ["M," pp. 57-58] Lowith adds, after some comments on Heidegger's pseudoradicalism: "In reality, the program of what Heidegger called 'pornography' was fully applied in November 1938 and became a reality for the Germans. No one could deny that on this point Streicher and Hitler acted as one and the same person" ("M," p. 58). What can we conclude from this interview? First, it was a conversation; but Heidegger was not one to express himself carelessly, even in conversation. He admitted, then, that he was speaking of his philosophy and

478

Maurice Blanchot

Thinking the Apocalypse

that the latter was the basis for his political involvement. This is 1936, Hitler is totally in power, and Heidegger has resigned from his post as rector but distanced himself only from Krieck, Rosenberg, and all those for whom anti-Semitism was the expression of a biological and racist ideology. Now, what did he write in 1945? "I believed that Hitler, after taking responsibility for the whole people in 1933, would dare to dissociate himself from the party and its doctrine, and this all would take the form of a renovation and unifying with the goal of responsibility for the entire West. This conviction was an error that I recognized after the events of June 30, 1934 [the Night of the Long Knives, the murder of Ernst Rohm, and the dispersion of the SA]. In 1933 I had indeed stepped in to say yes to the national and the social, but not at all to nationalism-nor the intellectual and metaphysical foundations that underlay biologism and the party d ~ c t r i n e . " ~ If indeed this was his idea, he said nothing of it to Lowith in 1936: he still maintained his trust in Hitler, wore the Nazi insignia on his lapel, and found only that things were not going fast enough but one only had to endure and hold fast. By saying he preferred the national to nationalism, he was not using one word in place of another; this preference is also at the basis of his thought and expresses his deep attachment to the land, that is, the homeland (Heimat),his stance in favor of local and regional roots (not that far removed from Auguste Maurice Barres' hatred of the "uprooted," a hatred that led the latter to condemn Alfred Dreyfus, who belonged to a people without connection to the land), and his loathing for urban life. But I am not going to develop these points, which, moreover, are well known but make me think that a kind of anti-Semitism was not alien to him and that it explains why he never, despite numerous requests, agreed to express his opinion on the extermination. Lacoue-Labarthe (and not Farias) reprints a terrible passage, which it pains one to repeat. What does it say? "Agriculture is now a mechanized food industry. As for its essence, it is the same thing as the manufacture of corpses in the gas chambers and the death camps, the same thing as the blockades and the reduction of countries to famine, the same thing as the manufacture of hydrogen bombs." This, according to Lacoue-Labarthe, is a scandalously inadequate statement, because all it retains of the extermination of the Jews is a reference to a certain technology and mentions neither the name nor the fate of the Jews. It is indeed true that at Auschwitz and elsewhere Jews were treated as industrial waste and that they were considered to be the effluvia of Germany and Europe (in that, the responsibility of each one of us is at issue). What was unthinkable and unforgivable in

4. Quoted in Jacques Derrida, Psyche': Inventions de l'autre (Paris, 1987).

Critical Inquiry

Winter 1989

4 79

the event of Auschwitz, this utter void in our history, is met with Heidegger's determined silence. And the only time, to my knowledge, that he speaks of the extermination, it is as a "revisionist," equating the destruction of eastern Germans killed in the war with the Jews also killed during the war; replace the word yew" with "eastern German," he says, and that will settle the a c ~ o u n tThat . ~ the Jews, who had committed no other sin than to be Jewish, were for this sole grievance to be doomed to the Final Solution is something, says Lacoue-Labarthe, for which there is no one to answer in history. And he adds, "At Auschwitz the God of the JudeoChristian West died, and it is no accident that the people whose destruction was sought were the witnesses, in this West, of another origin of God that had been worshipped and had inspired thinkers there-if it is not even perhaps another God, one that remained free of the Hellenistic and Roman distortions of the first." Allow me after what I have to say next to leave you, as a means to emphasize that Heidegger's irreparable fault lies in his silence concerning the Final Solution. This silence, or his refusal, when confronted by Paul Celan, to ask forgiveness for the unforgivable, was a denial that plunged Celan into despair and made him ill, for Celan knew that the Shoah was the revelation of the essence of the West. And he recognized that it was necessary to preserve this memory in common, even if it entailed the loss of any sense of peace, in order to safeguard the possibility for relationship with the other.

P.S.-A few more words concerning my own case. Thanks to Emmanuel Levinas, without whom, in 1927 or 1928, I would not have been able to begin to understand Sein und Zeit, or to have undergone the veritable intellectual shock the book produced in me. An event of the first magnitude had just taken place; it was impossible to diminish it, even today, even in my memory. This is certainly why I took part in the homage for Heidegger's seventieth birthday. My contribution was a page from L'Attente de l'oubli. A little later, Guido Schneeberger (to whom Farias owes a great deal) sent me or had sent to me by his publisher the speeches Heidegger made in favor of Hitler while he was rector. These speeches were frightening in their form as well as in their content, for it is the same writing and very language by which, in a great moment of the history of thought, we had been made present at the loftiest questioning, one that could come to us from Being and Time. Heidegger uses the same language to call for voting for Hitler, to justify Nazi Germany's break from the League of Nations, and to praise Schlageter. Yes, the

5. In a letter to Herbert Marcuse, which had been requested and received by him. But as Marcuse does not reproduce the letter, the terms are not exact.

480

Maurice Blanchot

Thinking the Apocalypse

same holy language, perhaps a bit more crude, more emphatic, but the language that would henceforth be heard even in the commentaries on Holderlin and would change them, but for still other reasons. Faithfully yours, Maurice Blanchot 10 November 1987

You might also like

- RETRACING THE UNGRUNDDocument20 pagesRETRACING THE UNGRUNDEge ÇobanNo ratings yet

- MARKUS - The Soul and Life - The Young Lukacs and The Problem of CultureDocument21 pagesMARKUS - The Soul and Life - The Young Lukacs and The Problem of CultureDaniel CassioNo ratings yet

- Carl Schmitt's Diaries Reveal His Inner Turmoil and Intellectual JourneyDocument21 pagesCarl Schmitt's Diaries Reveal His Inner Turmoil and Intellectual JourneyNRS7No ratings yet

- Emilio Gentile. Fascism As Political ReligionDocument23 pagesEmilio Gentile. Fascism As Political ReligionAdriano NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Gary Roth - Marxism in A Lost Century - A Biography of Paul MattickDocument358 pagesGary Roth - Marxism in A Lost Century - A Biography of Paul MattickErnad Halilović100% (1)

- Rodney Blackhirst - Rene Guenon - Saint of The Threshold PDFDocument5 pagesRodney Blackhirst - Rene Guenon - Saint of The Threshold PDFdesmontesNo ratings yet

- Journal Od Euroasian Affairs 1 - 2013Document114 pagesJournal Od Euroasian Affairs 1 - 2013zzankoNo ratings yet

- Norm and Critique in Castoriadis Theory of Autonomy PDFDocument22 pagesNorm and Critique in Castoriadis Theory of Autonomy PDFDiego Pérez HernándezNo ratings yet

- LUHMANN, Niklas. Political Theory in The Welfare State. 1990Document127 pagesLUHMANN, Niklas. Political Theory in The Welfare State. 1990VictorNo ratings yet

- Arthur Moeller Van Den Bruck: The Man and His Thought - Lucian TudorDocument11 pagesArthur Moeller Van Den Bruck: The Man and His Thought - Lucian TudorChrisThorpeNo ratings yet

- Messianicity' in Social TheoryDocument18 pagesMessianicity' in Social Theoryredegalitarian9578No ratings yet

- Bendersky On Carl SchmittDocument15 pagesBendersky On Carl SchmittsdahmedNo ratings yet

- Call To Revolution and Mystical AnarchismDocument4 pagesCall To Revolution and Mystical AnarchismtheontosNo ratings yet

- 2 Myths and Scapegoats: The Case of René GirardDocument15 pages2 Myths and Scapegoats: The Case of René GirardDaysilirionNo ratings yet

- Étienne Balibar On UniversalismDocument9 pagesÉtienne Balibar On UniversalismAkbar HassanNo ratings yet

- Taubes Liberalism PDFDocument24 pagesTaubes Liberalism PDFBruno FernandesNo ratings yet

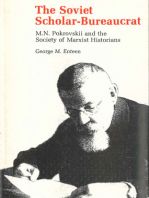

- The Soviet Scholar-Bureaucrat: M. N. Pokrovskii and the Society of Marxist HistoriansFrom EverandThe Soviet Scholar-Bureaucrat: M. N. Pokrovskii and the Society of Marxist HistoriansNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Giovanni GentileDocument17 pagesThe Philosophy of Giovanni GentileIntinion ClowngottesNo ratings yet

- DE BENOIST, Alain - The - European - New - Right - Forty Years Later - Against Democracy and Equality PDFDocument14 pagesDE BENOIST, Alain - The - European - New - Right - Forty Years Later - Against Democracy and Equality PDFTiago LealNo ratings yet

- The Fascist and The Fox - D - T - Pilgrim 3590887Document48 pagesThe Fascist and The Fox - D - T - Pilgrim 3590887carlos murciaNo ratings yet

- Mark Cowling: The Dialectic in Marx and Hegel - An OutlineDocument28 pagesMark Cowling: The Dialectic in Marx and Hegel - An OutlineAbhijeet JhaNo ratings yet

- Becoming Multitude: The AnomalistDocument10 pagesBecoming Multitude: The AnomalistAlberto AltésNo ratings yet

- Thymotic Politics: Sloterdijk, Strauss and NeoconservatismDocument37 pagesThymotic Politics: Sloterdijk, Strauss and NeoconservatismAnonymous Fwe1mgZNo ratings yet

- Georges Palante The Secular Priestly SpiritDocument12 pagesGeorges Palante The Secular Priestly Spiritpleh451100% (1)

- L Gordon South Atlantic Quarterly LibreDocument12 pagesL Gordon South Atlantic Quarterly Libremanuel arturo abreuNo ratings yet

- Ressentiment Paul and NietzscheDocument271 pagesRessentiment Paul and NietzscheMandate SomtoochiNo ratings yet

- Otto Hintze His WorkDocument33 pagesOtto Hintze His WorkAnonymous QvdxO5XTRNo ratings yet

- Domenico Losurdo, David Ferreira - Stalin - The History and Critique of A Black Legend (2019)Document248 pagesDomenico Losurdo, David Ferreira - Stalin - The History and Critique of A Black Legend (2019)PartigianoNo ratings yet

- Max Stirner Art and ReligionDocument9 pagesMax Stirner Art and ReligionAnthony ummo oemiiNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx and Max Stirner - ENGDocument22 pagesKarl Marx and Max Stirner - ENGlibermayNo ratings yet

- Deciphering an Unknown LanguageDocument18 pagesDeciphering an Unknown LanguageedifyingNo ratings yet

- Spirituality and Social Critique: A Modern Jewish PerspectiveDocument11 pagesSpirituality and Social Critique: A Modern Jewish PerspectivedkbradleyNo ratings yet

- Carl Schmitt, Political Romanticism, Translated by Guy Oakes, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 168 PPDocument4 pagesCarl Schmitt, Political Romanticism, Translated by Guy Oakes, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 168 PPAlejandro FielbaumNo ratings yet

- Myth and History - Blumemberg and CassirerDocument13 pagesMyth and History - Blumemberg and Cassirerrenato lopesNo ratings yet

- From Lukacs to Critical TheoryDocument17 pagesFrom Lukacs to Critical TheoryDaniel E. Florez Muñoz100% (1)

- Peter Sloterdijk's Generous SocietyDocument33 pagesPeter Sloterdijk's Generous SocietyIsaias BispoNo ratings yet

- Hannah Arendt's Encounter With MannheimDocument65 pagesHannah Arendt's Encounter With MannheimjfargnoliNo ratings yet

- Fredric Jameson, Badiou and The French Tradition, NLR 102, November-December 2016Document19 pagesFredric Jameson, Badiou and The French Tradition, NLR 102, November-December 2016madspeterNo ratings yet

- Bernard Stiegler The New Conflict of TheDocument21 pagesBernard Stiegler The New Conflict of TheChan PaineNo ratings yet

- New German Critique-ToCDocument120 pagesNew German Critique-ToCLuis EchegollenNo ratings yet

- Davenport Blumenberg On HistoryDocument75 pagesDavenport Blumenberg On HistoryWillem OuweltjesNo ratings yet

- Graeber Radical Social TheoryDocument4 pagesGraeber Radical Social TheoryAlexis KarkotisNo ratings yet

- GANGL - Taming The Struggle. Agonal Thinking in Nietzsche and MouffeDocument22 pagesGANGL - Taming The Struggle. Agonal Thinking in Nietzsche and MouffeJulián GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Mystical Millenarianism in The Early Modern Dutch RepublicDocument12 pagesMystical Millenarianism in The Early Modern Dutch RepublicRoy Den BoerNo ratings yet

- "Anti-Semitism": Soon It Will Be A CrimeDocument15 pages"Anti-Semitism": Soon It Will Be A CrimeRaúl VerderosaNo ratings yet

- Blumenberg's Response to Heidegger's Critique of Philosophical AnthropologyDocument28 pagesBlumenberg's Response to Heidegger's Critique of Philosophical AnthropologyhkassirNo ratings yet

- The Grandeur of Yasser Arafat PDFDocument5 pagesThe Grandeur of Yasser Arafat PDFsuudfiinNo ratings yet

- Cederberg - LevinasDocument259 pagesCederberg - Levinasredcloud111100% (1)

- GRIFFIN, R The Sacred Synthesis The Ideological Cohesion of FascistDocument26 pagesGRIFFIN, R The Sacred Synthesis The Ideological Cohesion of FascistBicicretsNo ratings yet

- The Lives of OthersDocument3 pagesThe Lives of OthersAjsaNo ratings yet

- Derrida, J - A Certain Madness Must Watch Over Thinking, (1995) 45 Educational Theory 273Document19 pagesDerrida, J - A Certain Madness Must Watch Over Thinking, (1995) 45 Educational Theory 273Leandro Avalos BlachaNo ratings yet

- The Earlt Literary Criticism of W. Benjamin-Rene WellekDocument12 pagesThe Earlt Literary Criticism of W. Benjamin-Rene WellekcmshimNo ratings yet

- LEVINE 1981 Sociological InquiryDocument21 pagesLEVINE 1981 Sociological Inquirytarou6340No ratings yet

- Nietzsche and The Bourgeois SpiritDocument4 pagesNietzsche and The Bourgeois SpiritRico PiconeNo ratings yet

- Heidegger S DescartesDocument27 pagesHeidegger S Descartesedakeskin83No ratings yet

- 2012 Heidegger Circle ProceedingsDocument176 pages2012 Heidegger Circle ProceedingsFrancois RaffoulNo ratings yet

- Tovar-Restreppo - Castoriadis-Foucault-and-Autonomy-New-Approaches-to-Subjectivity-Society-and-Social-Change PDFDocument177 pagesTovar-Restreppo - Castoriadis-Foucault-and-Autonomy-New-Approaches-to-Subjectivity-Society-and-Social-Change PDFGermánDíazNo ratings yet

- Douglas Moggach Politics Religion and Art Hegelian DebatesDocument369 pagesDouglas Moggach Politics Religion and Art Hegelian DebatesVanessa Costa da RosaNo ratings yet

- Taubes - Theology and The Philosophic Critique of ReligionDocument10 pagesTaubes - Theology and The Philosophic Critique of ReligionAlonzo LozaNo ratings yet

- Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911 - 1951From EverandWittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911 - 1951No ratings yet

- Ecole Toronto v21Document17 pagesEcole Toronto v21Tolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- WOLFE 2016 The Origin of SpeechDocument17 pagesWOLFE 2016 The Origin of SpeechTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- New Media Society 2016 Lagerkvist 1461444816649921Document15 pagesNew Media Society 2016 Lagerkvist 1461444816649921Tolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- Network 1976, A Script by Paddy ChayefskyDocument148 pagesNetwork 1976, A Script by Paddy ChayefskyTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- How To Look at Art by Ad ReinhardtDocument10 pagesHow To Look at Art by Ad ReinhardtTolle_Lege100% (1)

- Clear and To The Point. Stephen M KosslynDocument235 pagesClear and To The Point. Stephen M KosslynpiliNo ratings yet

- Pierrot Le Fou by Jean-Luc Godard: Complete ScriptDocument40 pagesPierrot Le Fou by Jean-Luc Godard: Complete ScriptTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- "The Operable Man. On The Ethical State of Gene Technology" by Peter SloterdijkDocument9 pages"The Operable Man. On The Ethical State of Gene Technology" by Peter SloterdijkTolle_Lege100% (1)

- Living in The InterregnumDocument22 pagesLiving in The InterregnumTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- Remarks On Administrative and Critical Communication ResearchDocument16 pagesRemarks On Administrative and Critical Communication ResearchTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- Scholarly Forerunners of Fascism by Svend Ranulf, 1939Document19 pagesScholarly Forerunners of Fascism by Svend Ranulf, 1939Tolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- How literacy shapes mental health across culturesDocument14 pagesHow literacy shapes mental health across culturesTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- On Insanity by Leo TolstoyDocument13 pagesOn Insanity by Leo TolstoyTolle_LegeNo ratings yet

- Shiva Panchakshara StotramDocument5 pagesShiva Panchakshara Stotramjoseph0% (1)

- The Clavis or Key To The Magic of Solomon Sibley Hockley Peterson PDFDocument445 pagesThe Clavis or Key To The Magic of Solomon Sibley Hockley Peterson PDFOlatunji Adebisi Tunde100% (3)

- Filipinos Colonial MentalityDocument10 pagesFilipinos Colonial MentalityJune Clear Olivar LlabanNo ratings yet

- SGPS Rut 4Document398 pagesSGPS Rut 4gurvinder singh dhirajNo ratings yet

- Are You Really a ChristianDocument36 pagesAre You Really a ChristianZsombor LemboczkyNo ratings yet

- Shabana - Negation of Paternity in Islamic Law Between Li'an and DNA Fingerprinting2 PDFDocument46 pagesShabana - Negation of Paternity in Islamic Law Between Li'an and DNA Fingerprinting2 PDFIbnuKhams100% (1)

- Benoytosh Bhattacharyya-Introduction To Buddhist Esoterism-Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office (1964)Document219 pagesBenoytosh Bhattacharyya-Introduction To Buddhist Esoterism-Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office (1964)dsudipta100% (2)

- Chemistry Canadian 2nd Edition Silberberg Test BankDocument25 pagesChemistry Canadian 2nd Edition Silberberg Test BankKendraReillytxcr100% (57)

- Church Age Closing Out as Jesus Returns to Establish His KingdomDocument7 pagesChurch Age Closing Out as Jesus Returns to Establish His KingdomJulie WelchNo ratings yet

- Fuller's Natural Law TheoryDocument19 pagesFuller's Natural Law TheoryHeidi Hamza67% (3)

- Tome of QayinDocument14 pagesTome of QayinDakhma of Angra Mainyu33% (3)

- Rilke and TwomblyDocument19 pagesRilke and TwomblyTivon RiceNo ratings yet

- Habib Tanvir: Tuning The Folk and The ModernDocument10 pagesHabib Tanvir: Tuning The Folk and The ModernAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- AncestorsDocument12 pagesAncestorsKyle TingNo ratings yet

- Five Elements Tai Chi Chuan Theory In-DepthDocument10 pagesFive Elements Tai Chi Chuan Theory In-DepthCésar EscalanteNo ratings yet

- OccultationDocument172 pagesOccultationQanberNo ratings yet

- Considering Gayatri Spivak As A Shakta TantricDocument4 pagesConsidering Gayatri Spivak As A Shakta TantricrhapsodysingerNo ratings yet

- No-Nonsense Buddhism For BeginnersDocument126 pagesNo-Nonsense Buddhism For Beginnersorchidocean5627100% (9)

- Caste System Compilation PDFDocument17 pagesCaste System Compilation PDFBond__001No ratings yet

- Chilhood Years of Rizal in CalambaDocument6 pagesChilhood Years of Rizal in CalambaMa. Raphaela UrsalNo ratings yet

- Arkitektura ShkodraneDocument7 pagesArkitektura ShkodraneEridona ZekajNo ratings yet

- THESIS111Document87 pagesTHESIS111batmanNo ratings yet

- TERRORISM IN THE PHILIPPINES: KEY GROUPS AND ATTACKSDocument81 pagesTERRORISM IN THE PHILIPPINES: KEY GROUPS AND ATTACKSianNo ratings yet

- The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570) Larte Et Prudenza Dun Maestro Cuoco (The Art and Craft of A Master Cook) (Lorenzo Da... (Scully, Terence)Document796 pagesThe Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570) Larte Et Prudenza Dun Maestro Cuoco (The Art and Craft of A Master Cook) (Lorenzo Da... (Scully, Terence)678ojyhdsfdiopNo ratings yet

- Gala (Priests)Document2 pagesGala (Priests)mindhuntNo ratings yet

- Ain Soph - The Endless One PDFDocument7 pagesAin Soph - The Endless One PDFAgasif AhmedNo ratings yet

- (Edwin Diller Starbuck) The Psychology of ReligionDocument452 pages(Edwin Diller Starbuck) The Psychology of Religionİlahiyat Fakkültesi Dergi Yayını Dergi Yayını100% (1)

- Agape - November, 2013Document36 pagesAgape - November, 2013Mizoram Presbyterian Church SynodNo ratings yet

- The Legend of Rawa PeningDocument17 pagesThe Legend of Rawa PeningAntoni FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- SQP 20 Sets HistoryDocument123 pagesSQP 20 Sets Historyhumanities748852No ratings yet