Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hartfield 1108 Appeal 13 14 00238 CV Reply FILED.20140620

Uploaded by

cbsradionewsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hartfield 1108 Appeal 13 14 00238 CV Reply FILED.20140620

Uploaded by

cbsradionewsCopyright:

Available Formats

i

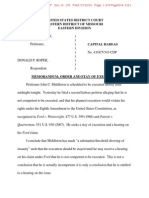

No. 13-14-00238-CV

IN THE

THIRTEENTH COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE STATE OF TEXAS

Jerry Hartfield,

Appellant,

vs.

The State of Texas,

Appellee.

_________________________________

APPELLANTS REPLY TO STATES BRIEF

_________________________________

David R. Dow

Texas Bar No. 06064900

ddow@central.uh.edu

Jeffrey R. Newberry

Texas Bar No. 24060966

jrnewber@central.uh.edu

University of Houston Law Center

100 Law Center

Houston, Texas 77204-6060

TEL: (713) 743-2171

FAX: (713) 743-2131

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................... ii

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................... iii

APPELLANTS REPLY TO STATES BRIEF ....................................................... 1

I. Mr. Hartfields claim is cognizable in his application filed pursuant to

Article 11.08. ................................................................................................... 4

A. The CCA recognized that the concerns that ordinarily make a pretrial

application an inappropriate vehicle by which to raise a speedy trial claim

are not present in Hartfields case. .................................................................. 4

B. Mr. Hartfields case is fundamentally different from every speedy trial case

cited by the State. ............................................................................................ 9

II. With respect to the second Barker factor, the State misconstrues Vermont v.

Brillon, 556 U.S. 81 (2009). .......................................................................... 16

III. The trial courts ruling that Mr. Hartfield has not waived the attorney-client

privilege was correct. .................................................................................... 19

IV. The State is correct that the third Barker factor is not concerned with

whether Hartfield could formulate a properly-pled speedy-trial claim ......... 22

PRAYER ................................................................................................................. 24

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ................................................................................ 25

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE ....................................................................... 25

iii

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Barker v. Wingo,

407 U.S. 514 (1970) ........................................................................................ 5

Bennet v. State,

818 S.W.2d 199 (Tex. App.Houston [14th Dist.] 1991) ........................... 15

Ex parte Burgett,

850 S.W.2d 267 (Tex. App.Fort Worth 1993) .......................................... 15

Ex parte Doster,

303 S.W.3d 720 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010) .................................................... 4, 9

Ex parte Graves,

271 S.W.3d 801 (Tex. App.Waco 2008, pet. refd) .................................. 13

Ex parte Jones,

449 S.W.2d 59 (Tex. Crim. App. 1970) ........................................................ 10

Ex parte Lamar,

184 S.W.3d 322 (Tex. App.Fort Worth 2005, pet. refd) .......................... 14

Ex parte Weise,

55 S.W.3d 617 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001) ........................................................ 10

Ex parte Wilson,

956 S.W.2d 25 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) ........................................................ 21

Graves v. Dretke,

442 F.3d 334 (5th Cir. 2006) ......................................................................... 13

Hartfield v. Thaler,

403 S.W.3d 234 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013) ................................................ 2, 3, 4

Lizcano v. State,

No. AP-75,879, 2010 WL 181772 (Tex. Crim. App. May 5, 2010) ............... 2

iv

Ordunez v. Bean,

579 S.W.2d 911 (Tex. Crim. App. 1979) ........................................................ 4

Smith v. Gohmert,

962 S.W.2d 590 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998) .................................................. 4, 11

State v. Munoz,

991 S.W.2d 818 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999) ...................................................... 18

United States v. MacDonald,

435 U.S. 850 (1978) ................................................................................ 4, 5, 6

Vermont v. Brillon,

556 U.S. 81 (2009) .................................................................................. 16, 17

Vermont v. Brillon,

955 A.2d 1108 (Vt. 2008), revd, 556 U.S. 81 (2009) ............................ 16, 17

Zamorano v. State,

84 S.W.3d 643 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002) .......................................................... 5

Statutes

Tex. Disciplinary R. Profl Conduct 1.05 ................................................................ 20

Tex. R. App. P. 74.9 .................................................................................................. 8

Tex. R. Evid. 503 ..................................................................................................... 20

1

No. 13-14-00238-CV

IN THE

THIRTEENTH COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE STATE OF TEXAS

Jerry Hartfield,

Appellant,

vs.

The State of Texas,

Appellee.

_________________________________

APPELLANTS REPLY

1

TO STATES BRIEF

_________________________________

TO THE HONORABLE JUDGES OF THE THIRTEENTH COURT OF

APPEALS:

On March 4, 1983, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals issued its mandate

to the 130th Judicial District Court that that court give Mr. Hartfield the new trial

which the CCA had ordered he was due in 1980 (II C.R. at 201-02, Hartfield v.

1

In this reply, Mr. Hartfield addresses only those assertions on the part of the State that

he deems warrant response. He does not abandon any arguments made in his amended brief.

2

State, 13-14-00240-CR).

2

Seven and one half years ago, with the assistance of a

fellow inmate, Jerry Hartfield a man who reads and writes on a first grade level

3

began to alert the State that he had never received the new trial. Hartfield first

alerted the State in a supplement to a habeas application filed pursuant to Article

11.07 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure (II R.R. at 73). Two months later,

in January 2007, he asked the CCA to compel a new trial through a petition for a

writ of mandamus.

4

Petition for Writ of Mandamus, In re Hartfield, No. WR-

66,609-02 (Tex. Crim. App. Jan. 31, 2007) (attached as Exhibit E to Appellants

Brief). He next attempted to raise his speedy trial claim in May 2007 in another

application filed pursuant to Article 11.07 (II C.R. at 213, Hartfield v. State, No.

13-14-00240-CR). Five months later, in October 2007, Hartfield began attempting

to raise his claim in the federal courts by filing both a petition for a writ of habeas

2

For the same reasons as those given in Appellants amended brief at 5 n.1, it is

necessary at times in this reply to cite the clerks record filed in Cause No. 13-14-00240-CR.

3

Despite the States contrary assertion, see States Brief at 67, Lizcano v. State, No. AP-

75,879, 2010 WL 181772 (Tex. Crim. App. May 5, 2010) does not support the States claim that

Hartfield cannot rely upon the report of Dr. Owens from his 1978 trial. Lizcano merely extended

the holding of Lagrone v. State, 942 S.W.2d 602 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997) to psychological

examinations to determine mental retardation. Lizcanos holding is that when a defendant

demonstrates intent to introduce evidence of mental retardation, a trial court may order the

defendant to submit being examined by an independent, state-sponsored psychological

examination. Lizcano, 2010 WL 181772 at *8 (emphasis added). It does not support the

States proposition that Hartfield may not rely on the report in these proceedings in the absence

of the Courts acting on the States Lagrone motion. Moreover, the State is the party that offered

Dr. Owens report into evidence in these proceedings at the December 19 hearing as part of its

Exhibit 1.

4

Despite the States contrary assertion, see States Brief at 6 n.5, as the CCA has made

clear its denial of relief on these pleadings was not because it found his speedy trial claim to be

without merit. Hartfield v. Thaler, 403 S.W.3d 234, 240 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013) ([O]ur denial

of [Hartfields] application for writs of habeas corpus and mandamus were based on his failure to

follow the proper procedure).

3

corpus and a petition for a writ of mandamus that asked the federal district court to

order the State to either retry him or release him. Throughout the next six years

that his petition was pending in the federal courts, the State took no action

whatsoever toward bringing him to trial. Federal proceedings culminated in the

Fifth Circuits certifying a question regarding the status of Hartfields conviction

and sentence to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in December 2012.

Over one year ago, on June 12, 2013, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

answered the question and resoundingly affirmed what Jerry Hartfield already

knew: he has been held by the State for over thirty years under no conviction or

sentence. Hartfield v. Thaler, 403 S.W.3d 234, 240 (Tex. Crim. App. 2013). The

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals suggested that Mr. Hartfield seek release from

his unlawful custody by filing, in the trial court, a pre-trial petition for writ of

habeas corpus. See id. Immediately on the heels of the CCAs ruling, exactly one

year ago, Mr. Hartfields counsel heeded the suggestion of the Court and filed such

a petition (I C.R. at 6-16). It was only then that the State began to take action

toward bringing Mr. Hartfield to trial. However, as proceedings in the court below

have revealed, the passage of time has prejudiced his ability to present a defense to

such a degree that no trial could possibly be fair. Hartfields right to a speedy trial

has been violated. This Court should order his immediate release from an unlawful

confinement that now exceeds three decades.

4

I. Mr. Hartfields claim is cognizable in his application filed pursuant to

Article 11.08.

A. The CCA recognized that the concerns that ordinarily make a

pretrial application an inappropriate vehicle by which to raise a

speedy trial claim are not present in Hartfields case.

Whether it intended to overrule precedent or merely recognized that Mr.

Hartfields case is unique, the Court of Criminal Appeals clearly indicated in its

June 12, 2013 opinion that filing an application under Article 11.08 was one of two

means by which Mr. Hartfield could raise his speedy trial claim. See Hartfield,

403 S.W.3d at 240 (Alternatively, Petitioner could have filed an application under

Article 11.08). The States dismissive attitude toward the CCA it characterizes

the Courts language as a single, fleeting sentence at one point in its reply and as

mere dicta at another, States Brief at 23, 30 is nothing more than an attempt

by the State to continue doing what it has been doing for more than thirty years,

namely: keep Mr. Hartfield incarcerated while he is under no conviction or

sentence. Hartfield, 403 S.W.3d at 240.

The State correctly observes that CCA precedent regarding speedy trial

claims is grounded in the Supreme Courts opinion in United States v. MacDonald,

435 U.S. 850 (1978). States Brief at 19-20; see also Ex parte Doster, 303 S.W.3d

720, 725-26 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010); Smith v. Gohmert, 962 S.W.2d 590, 593

(Tex. Crim. App. 1998); Ordunez v. Bean, 579 S.W.2d 911, 914 (Tex. Crim. App.

1979). But the MacDonald Courts holding that a denial of a speedy trial motion

was not immediately appealable was based on two grounds that were present in the

5

particular case of Mr. MacDonald: that it is typically difficult to determine the

degree to which a defendant has been prejudiced by the delay prior to the trial, and

that allowing immediate appeal on speedy trial issues would frustrate the purposes

of the Speedy Trial Clause. United States v. MacDonald, 435 U.S. at 859-60, 861-

62 (1978). These concerns of the MacDonald Court are present in most, perhaps

nearly all, speedy trial claims, but they are clearly not at issue in Mr. Hartfields

case.

The State concedes that the proper resolution of [a speedy trial] claim often

requires consideration of the impact of the delay upon the defendants ability to

present possible defenses. States Brief at 59 n.25 (quoting 43 George E. Dix &

John M. Schmolesky, Tex. Prac., Criminal Practice and Procedure 35: 26 (3d ed.)

(West 2013)); see also Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514, 530 (1970); Zamorano v.

State, 84 S.W.3d 643, 647-48 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002). And the State is correct to

observe that [t]his may be impossible to address without careful attention to the

trial evidence, its strengths, and possibly contradicting evidence. States Brief at

21 (quoting 43 George E. Dix & John M. Schmolesky, Tex. Prac., Criminal

Practice and Procedure 35: 26 (3d ed.) (West 2013)). The fact that this inquiry

may typically be impossible, however, is neither true nor relevant in Mr.

Hartfields case, because Mr. Hatfield was already previously tried. Although it

would require speculation to assess prejudice in the case of a defendant who has

not been tried, ascertaining the prejudice in Mr. Hartfields case would not require

any speculation whatsoever. We know what evidence the State would present at

6

trial because the State presented that evidence in its 1977 prosecution of Mr.

Hartfield. And, because of the proceedings in the court below, we know the

current state of that evidence. In short, the first concern expressed by the

MacDonald Court is irrelevant here.

The MacDonald Courts second concern was that allowing speedy trial

claims to be immediately appealed would threaten precisely the values manifested

in the Speedy Trial Clause. MacDonald, 435 U.S. at 862. Specifically, the Court

feared that delay caused by an interlocutory appeal would prejudice the

prosecutions ability to prove its case, increase the cost to society of maintaining

defendants subject to pretrial detention, and prolong the period during which

defendants released on bail may commit other crimes. Id. It is, of course,

laughable to suggest that those concerns are even remotely present in Mr.

Hartfields case.

The CCA ordered a new trial for Mr. Hartfield in 1980. Any prejudice that

would result to the State because of delay and any costs associated with

incarcerating Mr. Hartfield prior to trial have already long since been incurred.

Further, since the CCA issued its most recent opinion, affirming that Mr.

Hartfields incarceration in the Department of Corrections has been entirely

unlawful, Mr. Hartfield has acted with diligence and without delay in seeking relief

in the basis of his speedy trial claim. The CCA ordered a new trial thirty-three

years ago. Measured in that context, the additional time required to fully litigate

Mr. Hartfields speedy trial claim through this Article 11.08 proceeding would

7

constitute a tiny fraction of the delay that has occurred solely as a result of the

States wrongful detention of Mr. Hartfield. However, and importantly, the 11.08

proceedings have to date caused no delay in the new trial proceedings underway in

the trial court. Though it is Hartfields belief these 11.08 proceedings will prove

the new trial proceedings are impermissible, he has taken no action to cause any

delay in the new trial proceedings.

Moreover, any delay in the prosecution of Hartfield, any fault for any

increased difficulty to the State prosecuting its case, and any costs associated with

keeping Mr. Hartfield incarcerated during the delay, would all result from the

States own wrongful conduct. The CCA handed down its opinion ordering a new

trial in 1980. The order became final when the mandate issued on March 4, 1983.

For the next thirty years, the State took no action toward carrying out this dictate.

The State was content to allow Mr. Hartfield to remain in prison under no

conviction or sentence and allow taxpayers to foot the bill for that incarceration for

thirty years. Had Mr. Hartfield not initiated these proceedings, the State would

have been content to keep Mr. Hartfield incarcerated indefinitely in spite of the

CCAs mandate, in spite of any increasing difficulty in prosecuting him caused by

the delay, and in spite of the costs of incarcerating him.

United States v. MacDonald undergirds the CCAs previous rulings that

speedy trial claims are not immediately appealable and therefore not cognizable in

8

petitions filed pursuant to Article 11.08. Realizing that none of the concerns that

were present in MacDonald have any applicability to Mr. Hartfields case, the

Court of Criminal Appeals in June 2013 stated unequivocally that a petition filed

pursuant to Article 11.08 is one of two means by which Mr. Hartfield could

exhaust his claim. The statement was certainly not dicta, and it is inconceivable

that the CCA made this observation unthinkingly. On the contrary, the issues of

whether Mr. Hartfields claim has been exhausted and whether attempts to exhaust

would be futile were threshold issues in proceedings that were at that time pending

in the federal courts.

If the State believed that the CCA had erred in addressing the exhaustion

issue in its June opinion, a mechanism existed by which the State could have raised

that concern. Within fifteen days of the Court issuing its opinion, the State could

have filed a motion for rehearing. Tex. R. App. P. 74.9; see also I R.R. (Hearing

on States Motion to Dismiss Writ of Habeas Corpus) at 18 (Judge Estlinbaum:

The State could have filed a motion to rehear). The State did not file such a

motion. The CCAs June opinion authoritatively identifies the state law procedural

avenues applicable in Mr. Hartfields. One of those avenues is a habeas petition

under Article 11.08. This Court has the authority to grant relief and order Mr.

Hartfields immediate release.

9

B. Mr. Hartfields case is fundamentally different from every speedy

trial case cited by the State.

The State cites several cases in support of its claim that a pretrial habeas

application may not be used to assert a violation of the right to a speedy trial. But

every case relied on by the State is fundamentally and meaningfully different from

Mr. Hartfields.

For example, Ex parte Doster, 303 S.W.3d 720 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010),

States Brief at 18, did not even involve the same legal issue presented in Mr.

Hartfields case. The central legal issue in Doster was a failure to comply with the

Interstate Agreement on Detainers. Ex parte Doster, 303 S.W.3d 720, 721 (Tex.

Crim. App. 2010). Though noting the two were similar, the Court expressly stated

the speedy disposition of the charges under the IAD is not an identical right to

the constitutional right to a speedy trial. Id. at 727. Mr. Hartfields claim is

that his constitutional right to a speedy trial was violated. The Courts opinion on

whether pretrial habeas is available to a claim raised under the IAD is not

applicable to Hartfield.

Similarly, the relevant issue in Ex parte Weise, 55 S.W.3d 617 (Tex. Crim.

App. 2001), States Brief at 18, has no relevance to Mr. Hartfields case. The issue

in Weise was whether a pretrial writ of habeas corpus may issue on the ground

that a penal statute is being unconstitutionally applied because of the allegations in

10

the indictment or information. Ex parte Weise, 55 S.W.3d 617, 618 (Tex. Crim.

App. 2001). In the course of its discussion, the CCA observed that it had

previously held that a speedy trial claim could not be raised through a pretrial writ

of habeas corpus, but it neither amplified nor applied that holding in Weises case.

Id. at 620. Instead, the CCA in Weise simply held that the issue of whether the

illegal dumping statute requires a culpable mental state is not appropriate for

interlocutory appeal; that holding is wholly inapplicable to Hartfield. Id. at 621.

Finally, Ex parte Jones, 449 S.W.2d 59 (Tex. Crim. App. 1970), upon which

the State also relies, States Brief at 18, addresses a different procedural vehicle

from the one invoked by Mr. Hartfield. Although the CCAs opinion in Jones

lacks a great deal of details, it seems to address whether a denial of a motion to set

aside an indictment filed pursuant to Article 27.03 can be immediately appealed.

See Ex parte Jones, 449 S.W.2d. 59, 60 (Tex. Crim. App. 1970). Mr. Hartfield did

not raise his speedy trial claim in an Article 27.03 motion. Recognizing this

procedural vehicle would not allow for immediate appeal, Mr. Hartfield chose the

other procedural vehicle listed by the CCA as being available to him a petition

filed pursuant to Article 11.08.

5

5

The State is correct that counsel for Mr. Hartfield filed a motion to set aside the

indictment pursuant to Article 27.03 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure (I C.R. at 114-16,

Hartfield v. State, 13-14-00240-CR). Counsel filed the motion on the eve of the December 19

hearing (six months after filing the application filed pursuant to Article 11.08 and three weeks

11

The State also cites several cases that do superficially resemble Mr.

Hartfields, but closer examination reveals important differences between those

cases and Hartfields. For example, Smith v. Gohmert, States Brief at 18-20, does

address whether Smith could raise his constitutional speedy trial claim in a pretrial

writ of habeas corpus. Smith v. Gohmert, 962 S.W.2d 590, 591 (Tex. Crim. App.

1998). But the facts of the case are so dissimilar to the facts in Mr. Hartfields as

to make reliance on it untenable. Specifically, at the time he was charged with

capital murder, Smith had served only six months of a ninety-nine year sentence

for aggravated robbery. Id. Seven and one-half years later or roughly eight years

in to his ninety-nine year sentence he raised a speedy trial claim through a

petition for mandamus and/or habeas corpus relief challenging the capital murder

prosecution. Id. Observing that both mandamus and habeas corpus are

extraordinary remedies and, as such, are unavailable if there is an adequate remedy

at law, the CCA held that pursuing the speedy trial claim through an Article 27.03

motion was an adequate remedy for Smith precisely because he was many years

away from being parole eligible on his ninety-nine year sentence for aggravated

after the trial court denied the States motion to dismiss (I C.R. at 43, Hartfield v. State, 13-14-

00240-CR)) because the Court had indicated it believed that should it find in favor of Mr.

Hartfield, it needed some vehicle by which to dismiss the indictment. Both the motion and

counsels testimony at the December 19, 2013 hearing make clear the motion was filed solely for

this purpose and that the vehicle by which Hartfield raised his speedy trial claim was the

application filed pursuant to Article 11.08 (I C.R. at 114, Hartfield v. State, 13-14-00240-CR; II

R.R. at 1-3).

12

robbery. Hartfields situation is obviously and significantly different from

Smiths. Unlike Smith, who was in prison under a lawful ninety-nine year

sentence, Hartfield has been held by the State under no conviction or sentence for

thirty years. Unlike Smith, who would have remained in prison for decades

regardless of how his speedy trial challenge was resolved, Mr. Hartfield would be

entitled to immediate release if he were to prevail.

Moreover, perhaps because of the extraordinary and unique facts in Mr.

Hartfields case, the CCAs June opinion recognized that a motion to set aside the

indictment in Mr. Hartfields case was not an adequate remedy at law and that a

pretrial writ of habeas corpus was therefore an available vehicle through which to

raise his speedy trial claim. Forcing Hartfield to seek relief by raising his claim in

a pretrial motion to set aside the indictment would add potentially a year or more to

the already thirty years that he has been wrongfully imprisoned. A pretrial motion

is simply not an adequate remedy for Mr. Hartfield, and the Court of Criminal

Appeals recognized this very fact in its June 12 opinion.

The State also cites an opinion from the Waco Court of Appeals overruling a

speedy trial claim raised by Anthony Graves in a pretrial writ of habeas corpus.

States Brief at 20. The appellate court held that Gravess claim was not

cognizable because a pretrial motion filed pursuant to Article 27.03 was an

adequate remedy. Ex parte Graves, 271 S.W.3d 801, 807-08 (Tex. App.Waco

13

2008, pet. refd). Though Anthony Graves and Jerry Hartfield are similar in that

new trials were ordered for both, Gravess speedy trial claim is distinguishable

from Hartfields. The Fifth Circuit opinion ordering the district court to grant his

petition for a writ of habeas corpus was handed down on March 3, 2006. Graves v.

Dretke, 442 F.3d 334 (5th Cir. 2006). The Fifth Circuit did not hold that Graves

had been incarcerated in the absence of a valid conviction; indeed, it was the Fifth

Circuit itself that set aside the conviction. The same year the court of appeals

issued its judgment, Graves was released from TDCJ and transferred to the county

jail. See Offenders No Longer on Death Row,

http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/death_row/dr_offenders_no_longer_on_dr.html

(indicating Graves was released from TDCJ on September 7, 2006). Proceedings

in what would have been Mr. Gravess second trial were initiated soon after he was

returned to the county jail and had been initiated prior to Mr. Graves filing his

pretrial writ of habeas corpus.

Whereas Graves was transferred to the county jail a matter of months after

his conviction was vacated, Mr. Hartfield remained in the custody of the TDCJ for

more than thirty years following the opinion vacating his conviction. The Waco

courts opinion in Mr. Gravess case therefore cannot control Mr. Hartfields.

Ex parte Lamar, 184 S.W.3d 322 (Tex. App.Fort Worth 2005, pet. refd),

States Brief at 20, also differs factually from Mr. Hartfields case in an important

14

way. Lamar received one year of deferred adjudication in November 2003. Two

months later, in January 2004, Lamar was arrested on an unrelated matter. Id. at

323. And less than a month after that, on February 2, 2004, the State filed a

motion to adjudicate the original charge (i.e., the one to which Lamar had received

deferred adjudication). A year later, on February 22, 2005, Lamar filed a pretrial

writ of habeas corpus raising a speedy trial claim. That same day, the trial court

was prepared to set the case for trial. Id. Lamar asked the court not to set the case

for trial until after the speedy trial issue had been resolved. Finding that a pretrial

motion to set aside the indictment was an adequate remedy for Lamar, the Fort

Worth court held she was not entitled to habeas relief.

Unlike Lamar, Mr. Hartfield has not asked the Court to delay proceedings in

the States effort to retry him while his speedy trial claim is resolved. And more

importantly, Lamars trial court was ready to proceed to trial one year after the

State filed its motion to adjudicate nowhere near the thirty years Mr. Hartfield

has waited.

The remaining two cases relied upon by the State are just as far afield. Ex

parte Burgett, 850 S.W.2d 267, 267 (Tex. App.Fort Worth 1993), States Brief

at 20, involved a party who filed a speedy trial challenge a mere three months

following his arrest. And Bennet v. State, 818 S.W.2d 199, 200 (Tex. App.

Houston [14th Dist.] 1991), States Brief at 20, involved a defendant who appeared

15

in court eight times over the eleven months following his indictment and whose

trial commenced a mere fifteen months after he was indicted.

Every case relied upon or even cited by the State is so dramatically unlike

Mr. Hartfields case as to be irrelevant and uncontrolling. None of the applicants

in any of the cases cited by the State waited anywhere near the thirty years for their

trial that Mr. Hartfield has waited for his. Indeed, counsel is aware of no cases in

Texas or otherwise in which any applicant has waited an amount of time

comparable to that endured by Hartfield. Mr. Hartfields case is extraordinary and

probably unique; and its uniqueness was implicitly acknowledged by the CCA

when it acknowledged the availability of a pretrial writ of habeas corpus as one of

the two means by which Mr. Hartfield could raise a speedy trial claim to challenge

his lengthy and unlawful incarceration.

Because Hartfields claim is cognizable in an application filed pursuant to

Article 11.08, like the Court below did, this Court should address the merits of his

claim.

II. With respect to the second Barker factor, the State misconstrues

Vermont v. Brillon, 556 U.S. 81 (2009).

As was the case in the court below, the State would have this Court believe

that the failure to move the case forward at issue in Vermont v. Brillon, 556

U.S. 81 (2009), provides support for its proposition that the State is not responsible

16

for the delay in bringing Hartfield to trial. States Brief at 44-51. By removing

this one phrase from its context to support its argument that Hartfield then and

now incarcerated by the State had some affirmative duty to bring himself to trial

(though the CCAs 1983 mandate was obviously addressed to the State and not to

Hartfield), the State misconstrues Brillon. However, as the opinion below in

Brillon reveals, the failure to which the Court referred in fact involved a series of

different attorneys representing Brillon and Brillon taking affirmative steps to

delay the trial, Vermont v. Brillon, 955 A.2d 1108 (Vt. 2008), revd, 556 U.S. 81

(2009), and Brillon therefore provides no support for the States claim. Brillon

was arraigned on July 30, 2001. Id. at 1117. The first scheduled setting was an

evidentiary hearing set for August 15, but the day before the hearing, defense

counsel requested a continuance. Id. The next setting noted in the opinion was

scheduled for October 2, but counsel again asked for a continuance. Id. The State

asked for the trial to be set for February 2002, but four days before jury selection

was to begin, defense counsel filed another motion for continuance. Id. Brillon

then told his attorney he was fired, and counsel filed a motion to withdraw. Id. at

1118. A new attorney was appointed who felt he was conflicted, so the court

appointed a third. Id. Three months later, Brillon filed a pro se motion seeking to

have the third attorney removed. Id. This pattern continued throughout the period

of delay. Though Brillon was upset with his attorneys asking for continuances and

17

failing to communicate properly with him delays he said amounted to them

failing to move his case forward and though he requested to be tried promptly,

the Vermont Supreme Court erred in attributing this delay cause by Brillons

counsel to the State. Vermont v. Brillon, 556 U.S. 81, 92 (2009). Had

Hartfields trial counsel taken affirmative steps such as requesting continuances or

had counsel merely agreed to continuances sought by the State, these actions

would be attributable to Hartfield, and it would be appropriate to find him

responsible for any portion of delay caused by those actions. However, to suggest

that Brillon stands for the proposition that Hartfield is responsible for the delay

because trial counsel did nothing is to misrepresent the holding in Brillon. The

court below correctly recognized that Brillon does not stand for the proposition

that Hartfield is responsible for the delay in bringing him to trial (I C.R. at 169-71).

State v. Munoz, 991 S.W.2d 818 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999), States Brief at 43-

44, similarly provides no support for the States proposition that the delay should

be found to be attributable to Mr. Hartfield. Throughout the seventeen-month

period that Munozs trial was delayed the State and counsel for Munoz were

engaged in ongoing plea negotiations. State v. Munoz, 991 S.W.2d 818, 822 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1999). After the fourth plea offer, the parties reached an agreement,

but at the June 18, 1996 hearing, Munoz reneged on the deal and asked for a better

one. Id. at 823. The State refused and the court set a trial date for August 19,

18

1996. Id. The CCA held that delay caused by good faith plea negotiations is a

valid reason for the delay and should not be weighed against the prosecution. Id. at

824. Munoz provides no assistance to the State in trying to justify its delay in

bringing Hartfield to trial. Throughout the delay, the State was engaged in no good

faith negotiations with Hartfield. The State, ignoring the CCAs mandate, took no

actions. Munoz certainly does not stand for the proposition that the State can

justify the delay when he does absolutely nothing for thirty years to attempt to

resolve a case or bring it to trial.

The Court should find the court below was correct that [n]either Hartfield

nor his attorneys bear any blame for the 30-plus year delay in the case being re-

tried and that the second Barker factor weighs against the State (I C.R. at 171,

175).

III. The trial courts ruling that Mr. Hartfield has not waived the attorney-

client privilege was correct.

Robert Scardino represented Mr. Hartfield at his trial in 1978 and on direct

appeal. Attorneys from the Attorney Generals office procured an affidavit from

Scardino in 2008 during federal habeas proceedings. On January 29, 2009,

Magistrate Judge Stephen Smith of the Southern District of Texas granted Mr.

Hartfields motion to strike Scardinos affidavit because the affidavit violates the

19

attorney-client privilege. Order, Hartfield v. Quarterman, No. H-07-3676 (S.D.

Tex. Jan. 29, 2009). As the court recognized, while a

habeas petitioner implicitly waives the attorney-client privilege when

he asserts a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, see, e.g.,

Bittaker v. Woodford, 331 F.3d 715, 716 (9th Cir. 2003), a habeas

petitioner does not implicitly waive the attorney-client privilege when

he asserts other claims that do not question his attorneys

effectiveness. See, e.g., In re Lott, 139 Fed. Appx 658, 660-61 (6th

Cir. 2005). Hartfield has not asserted an ineffective assistance of

counsel claim in his petition nor has he expressly waived the attorney-

client privilege.

Id. The affidavit given by Mr. Scardino purports to disclose confidential

conversations conversations that Mr. Hartfield denies took place between

Scardino and Hartfield. The affidavit is a blatant ethical violation. A client has a

privilege to prevent any other person from disclosing confidential

communications made for the purpose of facilitating the rendition of professional

legal services to the client. Tex. R. Evid. 503(b)(1). A communication is

confidential if it is not intended to be disclosed to third persons. Tex. R. Evid.

503(a)(5). Except in certain circumstances, a lawyer shall not knowingly[] reveal

confidential information of a client or a former client to anyone, other than the

client, the clients representatives, or the members, associates, or employees of the

lawyers law firm. Tex. Disciplinary R. Profl Conduct 1.05(b).

As Magistrate Judge Smith recognized, a client can waive the privilege

when he raises a claim that his attorney provided ineffective assistance. See Tex.

20

R. Evid. 503(d)(3); Tex. Disciplinary R. Profl Conduct 1.05(c)(5)-(6). Mr.

Hartfield has never raised a claim to any court that Mr. Scardino provided

ineffective assistance. A lawyer may reveal confidential information when he has

been expressly authorized to do so by the client, the client consents, when the

lawyer has reason to believe it is necessary to prevent the client from committing a

criminal or fraudulent act, or to the extent revelation is necessary to rectify the

consequences of a clients criminal or fraudulent act. Tex. Disciplinary R. Profl

Conduct 1.05(c). None of these exceptions are applicable. Just as the affidavit

was stricken from the federal habeas proceedings, the court below was correct not

to consider the affidavit or to allow Scardino to testify about its contents at the

December 19, 2013 hearing. In its brief, the State argues that Mr. Hartfield

impliedly accused Mr. Scardino of being ineffective. States Brief at 70-71. The

State cites no examples and counsel is unaware of any examples of any court

finding that a defendant raised a claim of ineffective assistance impliedly. If it

were possible to impliedly raise a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel and

counsel in no way supports the proposition that such is possible raising the claim

would still require a defendant to demonstrate that his attorney performed his

duties in a manner that fell below an objective standard of reasonableness. Mr.

Hartfield would not be able to raise a claim either expressly or impliedly that

Mr. Scardino was ineffective for failing to inform him that he could file a writ of

21

habeas corpus to reverse the purported commutation because Mr. Scardino had no

duty to inform him of this. In Ex parte Wilson, 956 S.W.2d 25, the Court of

Criminal Appeals held that while an appellate attorney has an obligation to inform

a defendant of the result of his appeal and that he can pursue discretionary review

on his own, because the defendant has no right to counsel for purposes of

discretionary review, appellate counsel has no duty to express professional

judgment about possible grounds for review or to discuss the advantages of further

review. Ex parte Wilson, 956 S.W.2d 25, 26-27 (Tex. Crim. App. 1997). Just as a

defendant has no right to counsel for purposes of discretionary review, a defendant

has no right to counsel during state habeas proceedings unless he is under a

sentence of death. Mr. Hartfield was not under a sentence of death and had no

right to counsel in habeas proceedings. Scardino had no duty to discuss the

advantages of habeas proceedings. Without a duty, Hartfield could not either

expressly or impliedly raise a claim that Scardino was ineffective. Mr. Hartfield

has in no way expressly or impliedly waived the attorney-client privilege.

Furthermore, the affidavit and the testimony the State sought to elicit at the

hearing is irrelevant to the Barker analysis. As Hartfield has argued to this Court

and the court below and as the court below correctly recognized, finding Hartfield

responsible for the delay in bringing him to trial requires finding that he took

affirmative steps to delay the trial. Regardless of whether the purported

22

communication between Scardino and Hartfield occurred and Hartfield certainly

does not concede it did [n]either the [sic] Hartfield nor his attorneys sought

delays, continuances or took any other acts to prevent the Wharton County district

courts from trying the case at any time after mandate issued on March 4, 1983 (I

C.R. at 171). [T]he State has not identified one single action taken by Hartfield or

his attorneys to delay this case or prevent the case from being called to trial (I

C.R. at 171).

IV. The State is correct that the third Barker factor is not concerned with

whether Hartfield could formulate a properly-pled speedy-trial claim.

Judge Estlinbaum found that the only Barker factor that weighs against

Hartfield is the third factor: whether he asserted the right to a speedy trial (I C.R. at

191). He weighed this factor against Hartfield because he found that the

documents in which Hartfield expressed his desire for a new trial were not properly

pled. See, e.g., I C.R. at 178 (Hartfield did not file the writ on the Court of

Criminal Appeals prescribed form); I C.R. at 179 (faulting Hartfield for filing his

petition for a writ of mandamus in the wrong court); I C.R. at 180 (finding a

subsequent habeas application was not an assertion of his right to a speedy trial

because it failed to satisfy any of the exceptions that allow a court to consider a

subsequent application).

23

The State is correct that the third Barker factor is concerned with whether

[Hartfield] wanted a new trial, not whether he could formulate a properly-pled

speedy-trial claim. States Brief at 66. Hartfield expressed his desire for a new

trial in numerous documents all of which the State received notice. The court

below erred in finding these were not assertions of his right to a speedy trial. This

Court should find that because Hartfield did assert his right to a speedy trial, this

factor, like the other three, weighs against the State and that Hartfields right to a

speedy trial has been violated.

24

PRAYER

WHEREFORE, Mr. Hartfield respectfully prays this Court finds that his

right to a speedy trial under the Sixth Amendment has been violated. If this Court

finds that his constitutional right to a speedy trial has been violated, the indictment

against him should be dismissed with prejudice and he should be released.

Respectfully Submitted,

s/ David R. Dow

___________________________

David R. Dow

University of Houston Law Center

Texas Bar No. 06064900

100 Law Center

Houston, Texas 77204-6060

Tel. (713) 743-2171

Fax (713) 743-2131

s/ Jeffrey R. Newberry

__________________________

Jeffrey R. Newberry

Texas Bar No. 24060966

100 Law Center

Houston, Texas 77204-6060

Tel. (713) 743-6843

Fax (713) 743-2131

Counsel for Jerry Hartfield

25

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that on the 20th day of June 2014, a true and correct copy of the

above legal document was delivered to the following:

The Honorable Steven Reis

Criminal District Attorney

1700 7th Street, Room 325

Bay City, Texas 77414-5094

Tel. (979) 244-7657

Fax (979) 245-9409

s/ Jeffrey R. Newberry

_________________________

Jeffrey R. Newberry

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

This reply complies with the typeface requirements of Tex. R. App. P. 9.4(e)

because it has been prepared in a conventional typeface using MS Word in Times

New Roman 14-point font for body text and 12-point font for footnote text. The

reply contains 5,825 words, excluding the parts exempted by Tex. R. App. P.

9.4(i)(1)

s/ Jeffrey R. Newberry

_________________________

Jeffrey R. Newberry

You might also like

- WDYGTN EP 27 TranscriptDocument12 pagesWDYGTN EP 27 TranscriptcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- WDYGTN EP 26 TranscriptDocument7 pagesWDYGTN EP 26 TranscriptcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- "Dead Sound" ScriptDocument12 pages"Dead Sound" Scriptcbsradionews100% (1)

- Prejudgment Cert FinalDocument37 pagesPrejudgment Cert FinalcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Revised Luby Affidavit - Executed 12-23-2013 (05036427x9E3F7)Document4 pagesRevised Luby Affidavit - Executed 12-23-2013 (05036427x9E3F7)cbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Holmes DocumentDocument2 pagesHolmes DocumentcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Julis Jones v. Trammell FINALDocument19 pagesJulis Jones v. Trammell FINALcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Prejudgment Cert FinalDocument37 pagesPrejudgment Cert FinalcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- 2015 01.15 App Permission File Second HabeasDocument54 pages2015 01.15 App Permission File Second HabeascbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Final Rehearing Pet W AttachsDocument47 pagesFinal Rehearing Pet W AttachscbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Habeas Petition Filed in Earl Ringo CaseDocument28 pagesHabeas Petition Filed in Earl Ringo CasecbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Supp Pet CertDocument109 pagesSupp Pet CertcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Dkt. 1 - 07.21.14 Application To Vacate StayDocument23 pagesDkt. 1 - 07.21.14 Application To Vacate StaycbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- 2014 08 14 Sunshine PetitionDocument11 pages2014 08 14 Sunshine PetitioncbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Hartfield 1108 Cca PDR FILED.20140815Document52 pagesHartfield 1108 Cca PDR FILED.20140815cbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- 2014honeybees Mem RelDocument6 pages2014honeybees Mem RelcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- V14238&239, R14240&344 NVRDocument22 pagesV14238&239, R14240&344 NVRcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- PSP Complaint 07-29-14Document10 pagesPSP Complaint 07-29-14cbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Dkt. 21 - 07.10.14 OrderDocument15 pagesDkt. 21 - 07.10.14 OrdercbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Dkt. 2 - 07.22.14 Opposition To Application To Vacate Stay of ExecutionDocument23 pagesDkt. 2 - 07.22.14 Opposition To Application To Vacate Stay of ExecutioncbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Dkt. 35-2-07.21.14 Kozinski DissentDocument4 pagesDkt. 35-2-07.21.14 Kozinski DissentcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Dkt. 26 - 07.23.14 Emergency Motion For Stay of ExecutionDocument3 pagesDkt. 26 - 07.23.14 Emergency Motion For Stay of Executioncbsradionews100% (1)

- En BancDocument22 pagesEn BanccbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- A&f Survey Final DraftDocument2 pagesA&f Survey Final DraftcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Dkt. 21-1 - 07.16.14 Reply BriefDocument34 pagesDkt. 21-1 - 07.16.14 Reply BriefcbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Opposition To Motion To Dismiss Re Exhaustion (05043011x9E3F7)Document5 pagesOpposition To Motion To Dismiss Re Exhaustion (05043011x9E3F7)cbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Middleton Stay OrderDocument8 pagesMiddleton Stay OrdercbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Sunshine - Motion To Dismiss For Failure To Exhaust (05043001x9E3F7)Document6 pagesSunshine - Motion To Dismiss For Failure To Exhaust (05043001x9E3F7)cbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- Parsons 9th Cir Opinion 6-5-14Document63 pagesParsons 9th Cir Opinion 6-5-14cbsradionewsNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 2022 Chapter 1 UpdatedDocument46 pages2022 Chapter 1 UpdatedThùy Dung Nguyễn PhanNo ratings yet

- Sample California Motion For Discretionary Dismissal For Delay in ProsecutionDocument3 pagesSample California Motion For Discretionary Dismissal For Delay in ProsecutionStan Burman0% (1)

- Civil Suit For Permanent Prohibitory InjunctionDocument2 pagesCivil Suit For Permanent Prohibitory InjunctiongreenrosenaikNo ratings yet

- PSALM Vs Maunlad Homes, Inc.Document7 pagesPSALM Vs Maunlad Homes, Inc.lamadridrafaelNo ratings yet

- People vs. Inocencio GonzalesDocument3 pagesPeople vs. Inocencio GonzalesArvy AgustinNo ratings yet

- Carson Realty & Management Corporation vs. Red Robin Security Agency and Monica SantosDocument1 pageCarson Realty & Management Corporation vs. Red Robin Security Agency and Monica SantosAleah LS KimNo ratings yet

- Human Resources & Employment Law Cumulative Case Briefs and Notes Robert a Martin at (1) - ДокументDocument298 pagesHuman Resources & Employment Law Cumulative Case Briefs and Notes Robert a Martin at (1) - Документelassaadkhalil_80479No ratings yet

- SJ-2024-0018 - P011 - John Doe Nos. 1 Through 13 Memorandum of Law in Support of Their Request For Relief With AttachmentDocument15 pagesSJ-2024-0018 - P011 - John Doe Nos. 1 Through 13 Memorandum of Law in Support of Their Request For Relief With AttachmentBoston 25 DeskNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of Supreme CourtDocument11 pagesJurisdiction of Supreme CourtJasdeep KourNo ratings yet

- Paralegal or Legal Assistant or Executive AssistantDocument2 pagesParalegal or Legal Assistant or Executive Assistantapi-121633979No ratings yet

- Rule 66-1 - Aguinaldo Vs AquinoDocument2 pagesRule 66-1 - Aguinaldo Vs AquinoCali EyNo ratings yet

- Case Digest in ADR-Dela Merced v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of ManilaDocument2 pagesCase Digest in ADR-Dela Merced v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of ManilaAllan EsmaelNo ratings yet

- Lupong Tagapamayapa Incentives Awards (Ltia) Assessment FormDocument3 pagesLupong Tagapamayapa Incentives Awards (Ltia) Assessment FormMayumi Solatre100% (1)

- Manila Motors V FloresDocument1 pageManila Motors V FloresClarisa NatividadNo ratings yet

- McMillan v. Pennsylvania, 477 U.S. 79 (1986)Document21 pagesMcMillan v. Pennsylvania, 477 U.S. 79 (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. John Fiorilla, at No. 87-5445. United States of America v. Mary Fiorilla, at No. 87-5446, 850 F.2d 172, 3rd Cir. (1988)Document10 pagesUnited States v. John Fiorilla, at No. 87-5445. United States of America v. Mary Fiorilla, at No. 87-5446, 850 F.2d 172, 3rd Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-188551 People vs. EscamillaDocument9 pagesG.R. No. L-188551 People vs. EscamillaMichelle Montenegro - Araujo0% (1)

- Court upholds constitutionality of RA 9262Document1 pageCourt upholds constitutionality of RA 9262Albert RoseteNo ratings yet

- Brien 9780195594027 SCDocument17 pagesBrien 9780195594027 SCFredrick KabojaNo ratings yet

- 7) Triente, Sr. vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 70332-43, November 13, 1986Document15 pages7) Triente, Sr. vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 70332-43, November 13, 1986Sam AlbercaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Magdaleno Ypon vs. RicaforteDocument1 pageHeirs of Magdaleno Ypon vs. RicaforteGretch PanoNo ratings yet

- Garcia Vs CADocument10 pagesGarcia Vs CAMyra MyraNo ratings yet

- Agreed OrderDocument4 pagesAgreed OrdermikekvolpeNo ratings yet

- Randolph H. Cunningham v. Ashland Chemical Company, a Division of Ashland Oil, Inc. Fred Brothers, President Don Coticchia, Executive Vice President Rod Parsons, Vice President, Industrial Chemical Solvents Roy Beaver, Marketing Manager Jack Sweet, Business Manager Patrick H. Jayne, Regional Manager (Charlotte, Nc) Mike Stogner, Regional Manager (Atlanta, Ga) Phil Workman, District Manager (Charlotte, Nc) Howard Crawley, Marketing Manager Gregory H. Hill, Personnel (Charlotte, Nc), 900 F.2d 250, 4th Cir. (1990)Document5 pagesRandolph H. Cunningham v. Ashland Chemical Company, a Division of Ashland Oil, Inc. Fred Brothers, President Don Coticchia, Executive Vice President Rod Parsons, Vice President, Industrial Chemical Solvents Roy Beaver, Marketing Manager Jack Sweet, Business Manager Patrick H. Jayne, Regional Manager (Charlotte, Nc) Mike Stogner, Regional Manager (Atlanta, Ga) Phil Workman, District Manager (Charlotte, Nc) Howard Crawley, Marketing Manager Gregory H. Hill, Personnel (Charlotte, Nc), 900 F.2d 250, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dickerson v. Alewine - Document No. 5Document7 pagesDickerson v. Alewine - Document No. 5Justia.comNo ratings yet

- CA Dismisses Appeal of Principal Convicted of MalversationDocument3 pagesCA Dismisses Appeal of Principal Convicted of MalversationNoreenesse Santos100% (3)

- Susia Chan-Tan - Jesse C. Tan G.R. No. 167139, 25 February 2010, SECOND DIVISION (Carpio, .)Document1 pageSusia Chan-Tan - Jesse C. Tan G.R. No. 167139, 25 February 2010, SECOND DIVISION (Carpio, .)Teff QuibodNo ratings yet

- Activity 5.1 and 5.2Document8 pagesActivity 5.1 and 5.2Coleen Mae B. SaluibNo ratings yet

- Notarial Misconduct in Pale Digests 2017Document49 pagesNotarial Misconduct in Pale Digests 2017Jayson Racal100% (1)

- Republic of The Philippines, Local Civil Registrar of Cauayan, PetitionersDocument4 pagesRepublic of The Philippines, Local Civil Registrar of Cauayan, PetitionersLeogen Tomulto100% (1)