Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Zawadi Peter Mammba

Uploaded by

Gift Peter MammbaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Zawadi Peter Mammba

Uploaded by

Gift Peter MammbaCopyright:

Available Formats

Working Paper

1

OFF-FARM ACTIVITIES AND HOUSEHOLD POVERTY REDUCTION IN RURAL SETTING OF

DODOMA MUNICIPAL: A CASE OF NALA WARD

Zawadi P Mammba

giftmammba@outlook.com

ABSTRACT

The main objective of this paper is to address the importance of off-farm activities in eradicate household

poverty. The concept actual raised due to negligence of off-farming activities in most of Tanzania rural area,

it is only recent that the contribution of off-farm activities to household poverty has not been widely

addressed and campaigned for. The campaigning for increasing off-farm participation in rural area is

mostly with the view of gaining socio-economic popularity but not to equip rural household with strategic to

eradicate household poverty. The major findings reveal off farm activities as one of the aspects that need to

be address to transform rural economy in order to eradicate rural household poverty. Empirical results are

consisting with theoretical hypothesis that engagement in off-faming activities is affected by age, sex,

educational level, dependency ratio or family size. However, the empirical results show that, are consist with

the hypothesis that engagement in off-farming activities is influenced by sex, education level and family size

of household heads although, age and dependency ratio, age does not effluences household heads to

engaging in off-farm activities. Despite of neglecting of off-farm activities, there is evidence show the growth

of off-farm sector in rural Tanzania.

Keywords: Farm Activities, Off-farm Activities, Household Poverty, Rural Setting

INTRODUCTION

There is growing interest in off-farm income as research on rural economies is increasingly showing that

rural peoples livelihoods are derived from diverse sources and are not as overwhelmingly dependent on

agriculture as previously assumed (Gordon et al, 2001). The role of off-farm activities in promoting rural

economy and reducing poverty is well documented (Islam, 1984; Ranis and Stewart, 1993; Reardon, 1997;

Weijland, 1999; Lanjouw, 2001).

In Africa most countries have not yet met the criteria for a successful agricultural revolution and factor

productivity lags far behind the rest of the world. This situation has led to growth of scepticism in the

international development discourse about the relevance of agriculture to the growth of rural economy. As a

result, the promotion of off-farm activities as a pathway out of poverty has gained widespread support among

African countries and development agencies. Evidence shows that, off-farm activity in Africa is fairly evenly

divided across commerce, manufacturing and services that linked directly or indirectly to local agriculture or

small towns and is largely informal rather than formal (Reardon, 1997).

In Tanzania, Ellis (1999) provides a review of the large-scale sample survey evidence on the significance of

the off-farm sector in rural Tanzania. While the author accepts existence of measurement problems of off-

farm income, the results show that non-monetized incomes remain quite important, suggesting that the

transition out of subsistence agriculture is far from complete, but also non-farm income shares are fairly low

and there is no clear evidence of a marked expansion of these shares over time. Other studies, however, give

a different story. When studying Non-agricultural earnings in peri-urban areas of Tanzania (Lanjouw, 2001)

finds that off-farm income shares rise sharply and monotonically with quintiles defined in per capital income

terms. The recent Household Budget Survey of 2012 shows also that rural income appears to be increasingly

dependent on off-farm sources relative to on-farm income sources (Katera, 2013).

Working Paper

2

Although literature on off-farm activities is large, relatively few studies have examined how off-farm

activities contribute in eradicates household poverty. Moreover, the literature has been largely silent on how

governmental and non-governmental organization neglecting off-farm activities. These groups of papers

published in this special section helps to fill the knowledge gap. Hence these paper support theoretical

predictions that suggest diversification of off-farm and farm income- should base on marginal utility of

return. This is consistent with two theoretical arguments.

1

However, the substantial evidence are composed from Dodoma Region basically in Dodoma Municipal that

had been noticed among the poorest regional in Tanzania that characterized by low agriculture productivity

(arid land), massive unemployment and increasing population density (Msaki et al., 2013). Dodoma region is

one of the poorest areas in Tanzania because of frequent famines caused by semi-arid natural conditions

(Ndanga, 2012). Rainfalls are erratic, with an average annual precipitation level of 570mm, where 85% of the

rains do fall between December and April (Sakai, 2012). Such rainfall pattern in Dodoma makes it possible

to maintain agricultural societies through unstable due to capricious rainfall (Ndanga, 2012; Sakai, 2012).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Several measurements of off-farm activities constructed and used to analyse the relationship between age,

sex, education level, family size and dependency ratio with reasons for engaging in off-farm activities.

Economic theory also highlights the important of off-farm activities in household income.

In depth-interview conducted to the DARDO, WEO and VEO as key informants. In primary source the

structured questionnaire summarised, edited and coded before analysed. Statistical Package for Social

Sciences (SPSS) used to analyse quantitative data. Also descriptive statistics such as frequencies and

percentage used to obtain the variability and central tendencies of variable.

Respondents selected from each hamlet inconsideration of age, sex, educational background and wealth

status. Overall, total of 102 respondents selected whereby 93 from simple random sampling and 9 from

purposive sampling. Specifically, background information on farm, off-farm activities and studied area

background gathered from secondary source. In case of inferential statistics, multiple regressions were used

to predict reasons for engaging in off-farm activities as a targeted variable and the age of household head, sex

of the household head, education level of the household head, family size, and dependency ratio as a variable

to predict. The estimating equation is as follows:

2

Eoff-farm = Ag+Sx+Edl+D*+Fs+

1

The neoclassical farm household model predicted that a farm household chooses to work either on the farm or off-farm depending

on the marginal return from farm and off-farm labor (Singh et al, 1986).

For an individual, the action for off-farm participation is based on the comparison of the market wage rate and the reservation

wage. The reservation wage is the marginal value of time when none is allocated to off-farm work. An individual will participate in

off-farm work when the reservation wage is lower than the market wage (Benjamin et al., 1994).

2

To better capture the underlying reasons for engaging in off-farming activities, regressions (multiple linear) was employed.

Working Paper

3

Table 1: Variables Definitions

Name Definitions

Ag (age/Household head) Number of years

Sx (sex /Household heads Female or Male

Edl (education level/Household

heads)

Number of years spend in education (Primary School/Secondary

School/higher Learning Institution)

D* (dependency ratio) [(age 14 + aged 65)/ aged 15-64]*100

Fs (family size) Number of family member

Eoff-farm (reasons for engaging in

off-farm activities)

Reason for engaging in off-farm activities (1.00), Not reason for

engaging in off-farm activities (2.00)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We begin by discussing the background variables of respondents by focusing on age group whereby, the

household head with age of 18 and above are considered. As shown in Table 2, age distribution of the

respondents categorised into five bases; (1) 18-33; (2) 34-49; (3) 50-64 and (4) age above 65. Result does not

indicate household heads aged below 18 years old, also Table 2, indicates age groups by focusing on

frequency distribution and percentage contribution of each age groups. In case of household head sex, results

indicate 40.9% of household headed by female. Probably divorce and financial disability had leads female

households head to engaging in off-farm activities. Most respondents were married with very few cases of

separated household heads. Whereby, widow and widower were 16.1% and whos not married is 17.2%.

Also, the education level of household heads are ranked into 4 categories; not attending school, primary

education, secondary education, high learning institution. Results show that 55.9% of the heads of household

heads had attended primary schools with only 4.3% attended higher learning institution whereby 33.3% has

not gone to school. The presence of relatively high proportions of household heads with primary education

is due to the fact that, majority of rural dweller they are not realizes the potentiality of education to their daily

lives.

Working Paper

4

Table 2: Households Background Variables

Categories Frequency Percent

Age of Household heads

18-33 44 47.31

34-49 23 24.73

50-64 21 22.58

65 and above 5 5.38

Total 93 100

Sex of Household Heads

Male 55 59.14

Female 38 40.86

Total 93 100

Marital Status of Household Heads

Married 56 60.2

Not married 16 17.2

Widow/widower 15 16.1

Separated 6 6.5

Total 93 100

Education Level of Households

Not gone to school 31 33.3

Primary school education 52 55.9

Secondary school education 6 6.5

High learning institution/College/University 4 4.3

Total 93 100

Family Size

1-4 51 54.84

5-8 39 41.94

9 and above 3 3.22

Total 93 100

Dependency ratio

Below 14 164 44.1

Between 15 and 64 194 52.1

Above 65 14 3.8

Total 372 100

This paper indicates 54.8% of family size is range between 1 to 4 family members. And low family size is

range between 9 and above household members. In this study the dependency ratio includes those family

members under the age of 15 and over the age of 64. Also productive portion makes up the family members

ages between 15 and 64.

Reasons for Engaging In Off-Farm Activities

This section presents the results of econometric analysis on the reasons that lead household head to engaging

in off-farm activities. In this case, independent variables of age, dependency ratio, sex, family size and

education level of household head also dependent variable is reasons for engaging in off-farm activities are

used to formulate the model. During the model analysis, the Weighted Least Squares Regression (WLSR)

was applied on farm size variable in order to minimise error.

Working Paper

5

The summary model results indicate respectable level of prediction since the quality of the prediction of the

dependent variable, R is 0.618. That means, independent variables contribute 61.8% to the dependent

variable. Also explanation between variable (R-sq) is 38.2% and that indicate how age, sex, education,

dependency and family size act as a reasons for the household head to engaging in off-farm activities. The

variance in the criterion variable accounted 38.2% of Adjusted R-sq is 0.38. The independent variables

significantly predicted the dependent variable F (5, 73) = 9.028, p < .0005. As a result, the econometric

model is consequently fit the data since there is a statistically significant relationship between the reasons of

engaging in off-farm activities and the age, sex, education level, dependency ratio and family size of the

household head.

Table 3: Variable Contribution Measurement-Coefficients

Model Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized

Coefficients

T Sig.

B Std. Error Beta

(Constant) 2.801 0.547 5.124 0.000

Ag (Age/Household

heads)

0.010 0.085 0.014 0.117 0.907

Edl (Education level) 0.312 0.103 0.294 3.021 0.003

D* (Dependency ratio) 0.037 0.086 0.050 0.431 0.668

Fs (Family size) -0.201 0.071 -0.356 -2.848 0.006

Sx (Sex of the household) 0.534 0.190 0.288 2.802 0.006

The probability of the t statistic for independent variable of age is .117 for b coefficient is 0.907 > sig .05,

there is no statistically relationship between the ages of household head and the reasons for engaging in off-

farm activities. As a result, the age of household head is not driving force that can lead household head to

engage in off-farm activities.

There is statistical relationship between education level of household head and the reasons to engaging in off-

farm activities, since b coefficient is .003 < .05. As a result, the education level of household head is among

of the reasons that cause Nala dwellers to engage in off-farm activities.

The high or low number of dependant household member is not the reasons that cause household head to

engaging in off-farm activities, there is others reasons rather than dependency ratio. Result show that, t

statistics score .431 in which b coefficient score .668 > .05 sig. which imply non-statistical relationship

between variables.

The family size is among of the reasons that lead household head to engaging in off-farm activities, data

show that household with high number of member are considered to be more attracted to engage compare to

household with low number of member. Empirical result show household size has probability of t statistics of

-0.2848 for the b coefficient of .006 less than the level of significance, which indicates strong relationship.

Model analyses illustrate positive relationship in variable-sex where t statistical score .534 for b coefficient is

.006 2 < sig .05. Also result indicate male household a more likely to engaging in off-farm compared to

female household head. Male household head who engaged in off-farm activities was 59.14%.

Supplementary reasons that cause most of household heads to engage in off-farm activities mentioned as;

low income from agriculture; burden of maintaining large family and availability of off-farm opportunity in

rural area.

Working Paper

6

Interaction between Farm and Off-Farm Activities

Seasonality in agriculture causes most of the farmers to have excess labour during the slack season of

agriculture, which induces them to engage in off-farm activities. Results indicate that, off-farm activities

are much performed during dry seasonal compare to agriculture that practiced in rainfall seasonal and most

of the farmers engaged soon after harvested their crops. Data show the number of household who engaged in

off-farm activities during dry seasonal are 52 (56.8%) and the number of household who engaged in off-farm

activities during rainfall seasonal are 14 household equivalent to 15.1% while the household who engaged

during both seasonal (Dry and rainfall seasonal) are 26 (28.1%). Note that, majority are engaged in off-farm

activities during dry season by 56.8 %, as a result off-farm income cured most household from extremely

poverty during dry season.

Out of 93 household, farming incomes contribute Tsh. 56,034,500 in household income per annum whereby,

crop cultivation contributes Tsh. 47,273,500 and livestock keeping contribute Tsh. 8,761,000. Tsh.

151,342,000 obtained from different source of off-farm activities. Off-farm activities contribute much

compared to agriculture but in a real sense the contribution of off-farm is compounded collection from 17

different off-farm activities while agriculture is only 2 activities (crop cultivation and livestock keeping).

Rural household income much depends on farm and off-farm income in large extent, the interaction is much

influenced by income.

Most of the farmers are participating in off-farm activities mainly to supplement their agricultural income.

Excess labour and the agriculture seasonality are the key factors responsible for farmers to participate in off-

farm activities. Large family results in declining farm size which in turn results in low level of per capital

productivities and hence less income.

Figure 1: Average income from farm activities

Crop cultuvation,

Tsh. 508,312 , 84%

Livestock keeping,

Tsh. 94,204 , 16%

Rural off-farm activities in the study areas were classified into three categories; i) Business enterprises such

as shop keeping, petty trading, contractor services ii) Services such as salaried service in public and private

sector institutions, teachers, lawyer, village doctors and iii) Off-farm labour such as mechanics, wage

employment in rural business, transport operations, construction labour.

Working Paper

7

Figure 2: Average income from off-farm activities

Business

enterprises , Tsh.

805,172 , 49%

Tsh. Services,

455,892 , 28%

Off-farm labour ,

Tsh. 366,269 ,

23%

Contribution of off-farm activities to household poverty reduction

The effect of off-farm to household income analysed by compared household income distribution, with a

counterfactual off-farm income. Result show that, the average total household income from both activities

farm and off-farm are Tsh. 2,229,855. Out of that, average household income from farm activities are Tsh.

602,522 while off-farm activities are 1,627,333. If household income were composed by only farm activities

the household income could be Tsh. 602,522 equivalent to 27% of average total household income.

Whereby, off-farm activities contribute annual average household income of Tsh. 1,627,333 equivalent to

73% of total annual average household income, this imply, the contribution of off-farm activities to

household income is high compared with farm activities Table. 5

Table 4: Farm and off-farm income

Source of income Income per annum (Tsh.) Mean (n=93) Percentage

Off-farm activities 151,342,000 1,627,333 73

Farm activities 56,034,500 602,522 27

Farm and off-farm activities 207,376,500 2,229,855 100

The annual average household expenditure on meal is Tsh. 1,081,000 (46%), equivalent to Tsh. 3,000 per

day. Therapeutic Tsh. 26,055 (0.9%), clothing is Tsh. 78,000 (3.4%), school fees Tsh. 139,962 (2.7%), rent is

Tsh. 85,500 (0.086%), entertainment Tsh. 203,853 (4.0%), communication disbursement is Tsh. 175,475

(5.1%), ceremonial contribution is Tsh. 34,894 (0.32%), development contribution is Tsh. 4,427 (0.1%) and

other households expenditure Tsh. 1,315,534 (36.7%). It seems Nala dweller put more consideration to

unproductive activities rather than productive activities. Households spend the average of Tsh. 203,853 per

annum equivalent to 4.0% on refreshment and other unnecessary entertainment while spend only Tsh. 4,427

equivalent to 0.1% on development contribution. Results show Nala dwellers are much attracted by

ceremonial contribution than development contribution.

Part-time farming and multiple job holding have become strategies to support and stabilize households

income while off-farm employment is the only one strategy to deal with income fluctuations and risk

Working Paper

8

associated in agriculture. Study indicates 81 (87.1%) are self-employed, and only 12 (12.9%) households

head are permanent employed in different Governmental and Non-Governmental Organisation (NGOs).

CONCLUSIONS

The question of off-farming activities and household poverty reduction is not simple and unlikely to be

answered without empirical evidence. As a result, this paper examines the important of off-farm activities in

eradicating household poverty by analysing data quantitative and quantitatively.

Taken as a whole, this paper provides a cautionary tale for policy-maker institution and rural development

stakeholders that are eager to eradicate rural household poverty in order to transform rural economy. In that

case, policy options should not be limited to farming, but rather go beyond it to off-farm activities, since both

are equally important for rural economic growth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thanks H.I Mbise, R.N Masologo, N. Buretta and E. Makamba they contribute much on

the study. Equally authors would like to put on record our gratitude toward Nala Ward community for their

time and active participation throughout the period of the study.

REFERENCES

Gordon, A., and C. Craig, 2001. Rural non-farm activities and Poverty Alleviation in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Policy Series 14: 1-2

Reardon, T. 1997. Using evidence of household income diversification to inform study of the rural nonfarm

labour market in Africa. World Dev. 25 (5), 735 748

Haggblade, S., P.B. Hazell, and T. Reardon. 2007. Transforming the rural non-farm economy. John Hopkins

University Press, forthcoming. McMillan Ltd, Oxford, Baltimore, United State of America

Reardon, T., J.E Taylor, K. Stamoulis, P. Lanjouw and A. Balisacan, 2000. Effects of Non-Farm

Employment on Rural Income Inequality in Developing Countries: An Investment Perspective. Journal

of Agricultural Economics

Islam, R. 1984. Off-farm Employment in Rural Asia: Dynamic Growth or Proletarization? Journal of

Contemporary Asia. Vol. 14: 306-324.

Ranis, G., and F. Stewart. 1993. Rural non-agricultural activities in development: Theory and application.

Journal of Development Economics 40: 75-201.

Lanjouw, P., 2001. Rural non-agricultural sector and poverty in El Salvador. World Development, 29(3):

529-527. World Development, 27 (9): 1515-1530.

Ellis, F. 1999. Rural livelihood diversity in developing countries: Evidence and policy implications. ODI

Natural Resources Perspective 40.www.odi.org.uk/nrp

Katera, L. 2013. Off-Farm Incomes: a Haven for Women and Youth in Rural Tanzania? Working Paper-GD1

Singh, I., L. Squire, and J. Strauss. 1986. Agricultural Household Models: Extensions, Applications and

Policy. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Working Paper

9

Benjamin, C., and H. Guyomard. 1994. Off farm work Decisions of French Agricultural households.

Agricultural Household Modeling and Family Economics, Elsevier, Amsterdam

Msaki M.M., M.I. Mwenda, I.J. Regnard. 2013. Cereal Bank as a necessary Rural Livelihood Institute in

Arid Land, Makoja Village, Dodoma-Tanzania. Asian Economic and Financial Review-3(2):259-269.

Ndanga, J.P. 2012. Household Economy of wagogo: Contribution of income diversification in income

poverty reduction to smallholder farmers in Dodoma-Tanzania. Rural Development Policy and Agro-

pastoralism in East Africa. In Proceeding 4th International Conference on Moral Economy of Africa.

Fukui Prefectual Univerty.

Sakai, M. 2012. Famine and moral economy in agro pastoralist society: 60 years of rainfall data analysis.

Rural development policy and agro-pastoralism in East Africa. Fukui Prefectural University

You might also like

- Abang Doris EnuDocument48 pagesAbang Doris Enujohn100% (1)

- Easterly The Tyranny of Experts PDFDocument246 pagesEasterly The Tyranny of Experts PDFSaksham KohliNo ratings yet

- Wonderbag Report PDFDocument48 pagesWonderbag Report PDFAlphonsius WongNo ratings yet

- Poor Economics - A Radical Rethinking of The Way To Fight Global Poverty, by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo PDFDocument60 pagesPoor Economics - A Radical Rethinking of The Way To Fight Global Poverty, by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo PDFGg3650% (6)

- Feminist EconomicsDocument8 pagesFeminist EconomicsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Employment and Unemployment Rates Can Rise TogetherDocument12 pagesEmployment and Unemployment Rates Can Rise TogetherS Sohaib HGNo ratings yet

- What is Urban DesignDocument16 pagesWhat is Urban DesignkukdeNo ratings yet

- Human Capital Education and Health in Development EconomicsDocument20 pagesHuman Capital Education and Health in Development EconomicswinieNo ratings yet

- Feminist EconomicsDocument8 pagesFeminist EconomicsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Feminist EconomicsDocument8 pagesFeminist EconomicsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Professional Curriculum VitaeDocument17 pagesProfessional Curriculum VitaeAnonymous zeqDcNJuHNo ratings yet

- Caste As Social Capital: The Tiruppur StoryDocument5 pagesCaste As Social Capital: The Tiruppur Storyprasad_dvNo ratings yet

- Kabeer, 2015. Gender Poverty and InequalityDocument18 pagesKabeer, 2015. Gender Poverty and InequalityEduardo AguadoNo ratings yet

- Feminist EconomicsDocument8 pagesFeminist EconomicsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Save The Children ReportDocument309 pagesSave The Children ReportPriyanka Ved100% (2)

- Bank and Secrecy Law in The PhilippinesDocument18 pagesBank and Secrecy Law in The PhilippinesBlogWatchNo ratings yet

- Off-Farm Activities and Household Poverty Reduction: Empirical Evidence From Nala Ward, Dodoma Municipal, TanzaniaDocument9 pagesOff-Farm Activities and Household Poverty Reduction: Empirical Evidence From Nala Ward, Dodoma Municipal, TanzaniaZawadi MammbaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Child Labour in Mile 1 and Mile 3 of Rivers State Port HarcourtDocument9 pagesAnalysis of Child Labour in Mile 1 and Mile 3 of Rivers State Port HarcourtLucky WyneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 - Population, Urbanization, and The EnvironmentDocument52 pagesChapter 15 - Population, Urbanization, and The EnvironmentMary Singleton100% (1)

- Chapter OneDocument30 pagesChapter OneAyogu ThomasNo ratings yet

- Broken Aid in AfricaDocument14 pagesBroken Aid in AfricaJill Suzanne KornetskyNo ratings yet

- Nigeria Stability and Reconciliation Programme: Abuja, December 2012Document84 pagesNigeria Stability and Reconciliation Programme: Abuja, December 2012Opata OpataNo ratings yet

- 0 Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciencesbangalore, Karnatakaproforma For Registration of Subject For DissertationDocument19 pages0 Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciencesbangalore, Karnatakaproforma For Registration of Subject For DissertationAndri wijayaNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Child HealthDocument15 pagesResearch Proposal Child HealthAnonymous OCmtoF0zNo ratings yet

- Review of Sub-National Economic Development and Regeneration For Comprehensive Spending Review: Contribution From The UK Poverty ProgrammeDocument4 pagesReview of Sub-National Economic Development and Regeneration For Comprehensive Spending Review: Contribution From The UK Poverty ProgrammeOxfamNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Socioeconomic and Sociodemographic Variables On Obesity - Using Pooled Regression and Pseudo Panel ApproachDocument28 pagesThe Effect of Socioeconomic and Sociodemographic Variables On Obesity - Using Pooled Regression and Pseudo Panel Approachsheenu111No ratings yet

- Neglected Vagrant and Viciously Inclined The Girls of The Connecticut Industrial SchoolsDocument135 pagesNeglected Vagrant and Viciously Inclined The Girls of The Connecticut Industrial Schoolsphdt10% (1)

- Thesis Com 2015 Osah Olam OnisoDocument265 pagesThesis Com 2015 Osah Olam Onisopeps_0)No ratings yet

- Assessing Palliative Care Services for Cancer Patients in TobagoDocument30 pagesAssessing Palliative Care Services for Cancer Patients in TobagotaurNo ratings yet

- Du Plessis 2008Document317 pagesDu Plessis 2008carlos_mera4898No ratings yet

- Anthony Mogire Momanyi (Recovered)Document20 pagesAnthony Mogire Momanyi (Recovered)Kevin ObaraNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Unemployment On Economic Development in NigeriaDocument56 pagesThe Effect of Unemployment On Economic Development in Nigeriajamessabraham2No ratings yet

- The Role of Micro and Smallscale Enterprises in Poverty Reduction: The Case of Dugda Dewa Woreda Finchawa Town Southern EthiopiaDocument20 pagesThe Role of Micro and Smallscale Enterprises in Poverty Reduction: The Case of Dugda Dewa Woreda Finchawa Town Southern Ethiopiaiaset123No ratings yet

- Child Restorati0N Outreach-Lira: January 2010Document17 pagesChild Restorati0N Outreach-Lira: January 2010Alele VincentNo ratings yet

- Technical Compendium: Descriptive Agricultural Statistics and Analysis For ZambiaDocument98 pagesTechnical Compendium: Descriptive Agricultural Statistics and Analysis For ZambiaChola MukangaNo ratings yet

- Poverty Estimation and Measurement MethodsDocument6 pagesPoverty Estimation and Measurement MethodsYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- Urmi MukharjeeDocument13 pagesUrmi MukharjeeMahila Pratishtha JournalNo ratings yet

- Impact of SHG in Reduction of Urban Women Poverty in Hawassa (Thesis PPT 1)Document52 pagesImpact of SHG in Reduction of Urban Women Poverty in Hawassa (Thesis PPT 1)Fasil ShibruNo ratings yet

- Demographic Data SourcesDocument5 pagesDemographic Data SourcesAnanta RoyNo ratings yet

- Common Char of Developing NationsDocument5 pagesCommon Char of Developing NationsNicole CarlosNo ratings yet

- Abdellaoui 2019.NHB - FaqDocument5 pagesAbdellaoui 2019.NHB - FaqAbdel AbdellaouiNo ratings yet

- KENDALL COUNTY - Boerne ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseDocument15 pagesKENDALL COUNTY - Boerne ISD - 2006 Texas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseTexas School Survey of Drug and Alcohol UseNo ratings yet

- Poverty As A ChallengeDocument11 pagesPoverty As A ChallengeSumit palNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Development in EthiopiaDocument131 pagesAgricultural Development in Ethiopiaibsa100% (2)

- Migration R - U Causes and Consequence in EthDocument6 pagesMigration R - U Causes and Consequence in Ethatinkut SintayehuNo ratings yet

- Who Participates in Local Government - Evidence From Meeting MinutesDocument19 pagesWho Participates in Local Government - Evidence From Meeting MinutesDarren KrauseNo ratings yet

- Household Survey On Impact of Economic Crisis - 2023Document8 pagesHousehold Survey On Impact of Economic Crisis - 2023Adaderana OnlineNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Agricultural Innovations Adoption Among Cooperative and Non Cooperative Farmers in Imo State, NigeriaDocument7 pagesDeterminants of Agricultural Innovations Adoption Among Cooperative and Non Cooperative Farmers in Imo State, NigeriaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Urban Informal Sector Impacts of Indian Trade ReformDocument36 pagesUrban Informal Sector Impacts of Indian Trade ReformHassan MaganNo ratings yet

- Status Report On Broadband and Broadcast Access in The State of Madhya PradeshDocument52 pagesStatus Report On Broadband and Broadcast Access in The State of Madhya PradeshVikas SamvadNo ratings yet

- Patterns, Features and Impacts of Rural-Urban Migration in Antananarivo, Madagascar (July 2010)Document65 pagesPatterns, Features and Impacts of Rural-Urban Migration in Antananarivo, Madagascar (July 2010)HayZara MadagascarNo ratings yet

- Food Security and Nutritional StatusDocument184 pagesFood Security and Nutritional StatusJoviner Yabres LactamNo ratings yet

- Unemployment Problem in BangladeshDocument5 pagesUnemployment Problem in Bangladeshtarangamjh100% (1)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated BibliographyElenaNo ratings yet

- Thesis About Unemployment RateDocument5 pagesThesis About Unemployment RatePayForPaperCanada100% (1)

- 3 Gender StudiesDocument21 pages3 Gender StudiesKeo Chhay HengNo ratings yet

- Smallholder Farmers On Intercropping Practices in West Hararghe Zone Oromia National Regional State, EthiopiaDocument9 pagesSmallholder Farmers On Intercropping Practices in West Hararghe Zone Oromia National Regional State, EthiopiaPremier PublishersNo ratings yet

- Empirical Analysis of IITA Youth in Agribusiness Model As A Panacea For Solving Youth Unemployment Problem in NigeriaDocument8 pagesEmpirical Analysis of IITA Youth in Agribusiness Model As A Panacea For Solving Youth Unemployment Problem in NigeriaBen Asuelimen IJIENo ratings yet

- Education in A Pandemic:: The Disparate Impacts of COVID-19 On America's StudentsDocument61 pagesEducation in A Pandemic:: The Disparate Impacts of COVID-19 On America's StudentsJexNo ratings yet

- Ournal of Frican Conomies Olume Umber PPDocument26 pagesOurnal of Frican Conomies Olume Umber PPsadiapkNo ratings yet

- Food Security Status in NigeriaDocument16 pagesFood Security Status in NigeriaYaronBabaNo ratings yet

- DDDDDocument11 pagesDDDDaycheewNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Socio-Economic and Demographic Factors Affecting Household Main Source of Income in Somalia Using Binary Logistic Regression ApproachDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of Socio-Economic and Demographic Factors Affecting Household Main Source of Income in Somalia Using Binary Logistic Regression ApproachMohamed Hussein AbdullahiNo ratings yet

- Income Inequality in Urban EthiopiaDocument14 pagesIncome Inequality in Urban EthiopiaTolessaNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Rural Livelihood Strategies: The Case of Rural Kebeles of Dire Dawa AdministrationDocument14 pagesDeterminants of Rural Livelihood Strategies: The Case of Rural Kebeles of Dire Dawa AdministrationChuchu TayeNo ratings yet

- Importance of WagesDocument37 pagesImportance of WagesSAURAV law feedNo ratings yet

- Livelihood Diversification Boosts Rural IncomeDocument12 pagesLivelihood Diversification Boosts Rural IncomeZerihun SisayNo ratings yet

- CV Andaleeb UpdatedDocument3 pagesCV Andaleeb Updatedapi-280763569No ratings yet

- Ethiopian Civil Service University ProfileDocument13 pagesEthiopian Civil Service University ProfileBelaynew Walelgn100% (1)

- CV Mohsin GulzarDocument2 pagesCV Mohsin GulzarYousaf AsgharNo ratings yet

- Latin American Economic Development and The Role of AgricultureDocument5 pagesLatin American Economic Development and The Role of Agricultureillosopher94No ratings yet

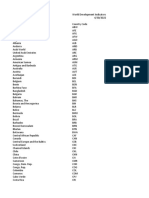

- API NY - GDP.PCAP - CD DS2 en Excel v2 3469429Document74 pagesAPI NY - GDP.PCAP - CD DS2 en Excel v2 3469429shahnawaz G 27No ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Defining of Development Economics (First Part)Document16 pagesLesson 2 - Defining of Development Economics (First Part)Rose RaboNo ratings yet

- 01 STEPHENSON Corruption Bibliography Dec 2015Document314 pages01 STEPHENSON Corruption Bibliography Dec 2015adriolibahNo ratings yet

- Week 3 Opportunity and Product PlanningDocument43 pagesWeek 3 Opportunity and Product PlanningkotturvNo ratings yet

- Imports of Goods and ServicesDocument79 pagesImports of Goods and ServicesAdnan MurtovicNo ratings yet

- Technology Development and Democracy International Conflict and Cooperation in The Information Age PDFDocument263 pagesTechnology Development and Democracy International Conflict and Cooperation in The Information Age PDFAntónio Martins CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- HE3003 Course Outline Aug 2014Document6 pagesHE3003 Course Outline Aug 2014Pua Suan Jin RobinNo ratings yet

- Todaro 1969Document12 pagesTodaro 1969sharpie_123No ratings yet

- Morality of Corporate GovernanceDocument19 pagesMorality of Corporate GovernanceSimbahang Lingkod Ng Bayan100% (1)

- The Impact Evaluation of Cluster Development Programs Methods and Practice PDFDocument218 pagesThe Impact Evaluation of Cluster Development Programs Methods and Practice PDFGonzalo FloresNo ratings yet

- JobsDocument422 pagesJobsGabriel CatañoNo ratings yet

- Economics Course Structure, Syllabus 20172Document121 pagesEconomics Course Structure, Syllabus 20172Saagar KarandeNo ratings yet

- Green Away 1991 New Growth TheoryDocument15 pagesGreen Away 1991 New Growth TheoryPREM KUMARNo ratings yet

- Aeo2006 enDocument588 pagesAeo2006 enMichel Monkam MboueNo ratings yet

- Lecture Planner (Economics) - PDF Only - Mission JRF June 2024 - EconomicsDocument2 pagesLecture Planner (Economics) - PDF Only - Mission JRF June 2024 - Economicskg704939No ratings yet

- Fforde Economic StrategyDocument29 pagesFforde Economic StrategyDinhThuyNo ratings yet

- BAH CBCS 12 Development Economics I 5th SemDocument3 pagesBAH CBCS 12 Development Economics I 5th Semspam spamNo ratings yet

- Economic development goals for sustained growthDocument5 pagesEconomic development goals for sustained growthBernardokpeNo ratings yet

- "Looking Back How Pakistan Became An Asian TIGER BY 2050": Pakistan Studies Book ReviewDocument6 pages"Looking Back How Pakistan Became An Asian TIGER BY 2050": Pakistan Studies Book ReviewTabish HamidNo ratings yet