Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Provisional Remedies Cases - Rule 57

Uploaded by

Jessa Ela Velarde0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

704 views501 pagesProvisional Remedies Cases_Rule 57

Original Title

Provisional Remedies Cases_Rule 57

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentProvisional Remedies Cases_Rule 57

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

704 views501 pagesProvisional Remedies Cases - Rule 57

Uploaded by

Jessa Ela VelardeProvisional Remedies Cases_Rule 57

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 501

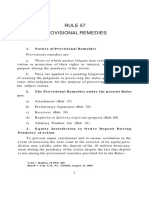

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

1 of 501

Section 1 ...................................................................................................... 4

Calo v. Roldan, 76 Phil. 445 ................................................................................. 4

KO Glass v. Valenzuela, 116 S 563 ........................................................................ 9

General v. De Venecia, 78 Phil. 780, July 30, 1947 ............................................. 14

Miailhe v. De Lencquesaing, 142 S 694 ............................................................... 16

Insular Savings Bank v. CA, 460 S 122 ................................................................ 19

Tan v. Zandueta, 61 Phil. 526 .............................................................................. 23

Walter Olsen v. Olsen, 48 Phil. 238 .................................................................... 25

Santos v. Bernabe, 54 Phil. 19 .............................................................................. 27

State Investment House v. CA, 163 S 799 .......................................................... 29

Aboitiz v. Cotabato Bus, 105 S 88 ....................................................................... 32

People's Bank & Trust Co. v. Syvel, 164 S 247 .................................................... 35

Adlawan v. Torres, 233 S 645 .............................................................................. 39

Claude Neon Lights v. Phil Advertising, 57 Phil. 607 (Case not Found) ......... 45

State Investment House v. Citibank, 203 S 9 .................................................... 46

Mabanag v. Gallemore, 81 Phil. 254 .................................................................... 53

Philippine Bank of Communications v. CA, February 23, 2001 ........................ 56

PCIB v. Alejandro, September 21, 2007 .............................................................. 60

Wee v. Tankiansee, February 13, 2008 ............................................................... 68

Metro, Inc. v. Laras Gift & Decor, November 27, 2009..................................... 72

Section 2 ................................................................................................... 76

Sievert v. CA, 168 S 692 ....................................................................................... 76

Davao Light v. CA, 204 S 343 ............................................................................. 79

Cuartero v. CA, 212 S 260 .................................................................................... 85

Salas v. Adil, 90 S 121 ........................................................................................... 89

La Granja v. Samson, 58 Phil. 378 ..................................................................... 92

Section 3 ................................................................................................... 94

KO Glass v. Valenzuela, 116 S 563 (See under Section 1 page 9) ...................... 94

Guzman v. Catolico, 65 Phil. 261 ........................................................................ 94

Jardine Manila Finance v. CA, 171 S 636 ............................................................ 97

Ting v. Villarin, 176 S 532 ................................................................................... 102

Cu Unjieng v. Goddard, 58 Phil. 482 ................................................................. 106

Carlos v. Sandoval, 471 S 266 ............................................................................. 112

Salgado v. CA, March 26, 1984, 128 SCRA 395 (Case Not Found!) ................. 127

PCIB v. Alejandro, September 21, 2007 (See under Section 1, page 60) .......... 127

Republic v. Flores, July 12, 2007 ......................................................................... 127

Section 4 ................................................................................................... 131

Arellano v. Flojo, 238 S 72 ................................................................................... 131

Calderon v. IAC, 155 S 531 .................................................................................. 134

Section 5 .................................................................................................. 139

Gotauco v. ROD, 59 Phil 756 ............................................................................. 139

Onate v. Abrogar (2

nd

Division), 230 S 181/131 .................................................. 140

Onate v. Abrogar (En Banc), 240/241 S 659 ..................................................... 144

HB Zachary v. CA, 232 S 329 ............................................................................. 149

Section 6 .................................................................................................. 159

Roque v. CA, 93 S 540 ........................................................................................ 159

Section 7 .................................................................................................. 164

Siari Valley Estates v. Lucasan, 109 Phil. 294 .................................................. 164

Ravanera v. Imperial, 93 S 589 .......................................................................... 167

Obana v. CA, 172 S 866 ...................................................................................... 175

Du v. Stronghold Insurance, 433 S 43 ................................................................ 181

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

2 of 501

Valdevieso v. Damalerio, 451 S 664 ................................................................... 186

Walker v. McMicking, 14 Phil. 668 ................................................................... 189

NBI v. Tuliao, March 24, 1997 ........................................................................... 193

Villanueva-Fabella v. Judge Ralph Lee, 419 S 440 ............................................ 197

Sebastian v. Valino, 224 S 256 ........................................................................... 203

Villareal v. Rarama, 247 S 493 ......................................................................... 206

Balantes v. Ocampo III, 242 S 327 ..................................................................... 210

Elipe v. Fabre, 241 S 249 ..................................................................................... 212

Roque v. CA, 93 S 540 (See under Section 6) .................................................... 215

Summit Trading v. Avendano, 135 S 397 ........................................................... 215

Chemphil Export and Import v. CA, 251 S 286 ................................................. 217

Tayabas Land v. Sharruf, 41 Phil. 382 ............................................................... 235

Gotauco v. ROD, 59 Phil. 756 (See under Section 5 page 139) ........................ 239

Rural Bank of Sta. Barbara v. Manila Mission, August 19, 2009 .................... 239

Section 8 ................................................................................................. 245

Engineering Construction v. NPC, 163 S 9 ....................................................... 245

RCBC v. Judge Castro, 168 S 49 .........................................................................250

The Manila Remnant v. CA, 231 S 281 ............................................................... 257

Chemphil Export and Import v. CA, 251 S 286 (See under Section 7 page 217)

............................................................................................................................262

Abinujar v. CA, April 18, 1995 ............................................................................262

National Bank v. Olutanga, 54 Phil. 346 ......................................................... 266

Perla Compania de Seguros v. Ramolete, 203 S 487 ....................................... 270

Tec Bi and co. v. Chartered Bank of India, 41 Phil.596 ....................................274

Consolidated Bank and Trust Corporation v. IAC, 150 S 591 .......................... 281

BF Homes v. CA, 190 S 262 ............................................................................... 286

Republic v. Saludares, 327 S 449 .......................................................................292

Section 12 ................................................................................................. 297

The Manila Remnant v. CA, 231 S 281 (See under Section 8 page 257) .......... 297

Insular Savings Bank v. CA, June 15, 2005 (See under Section 1 page 19) ...... 297

KO Glass v. Valenzuela, 116 S 563 (See under Section 1 page 9) .................... 297

Calderon v. IAC, 155 S 531 (See under Section 4 page 134) .............................. 297

Security Pacific Assurance Corp. v. Tria-Infante, 468 S 526 ......................... 298

Section 13 ................................................................................................ 304

Jopillo, Jr. v. CA, 167 S 247 ................................................................................ 304

Mindanao Savings Loan v. CA, 172 S 480 ........................................................ 308

Benitez v. IAC, 154 S 41 ...................................................................................... 314

Davao Light v. CA, 204 S 343 (See under Section 2 page 79) .......................... 317

Cuartero v. CA, 212 S 260 (See under Section 2 page 85) ................................. 317

Uy Kimpang v. Javier, 65 Phil 170 (1937) ........................................................... 318

Filinvest Credit v. Relova, 117 S 420 ................................................................... 323

Miranda v. CA, 178 S 702 ................................................................................... 329

Adlawan v. Torres, 233 S 645 (see under Section 1 page 39) ............................ 331

Peroxide Philippines Corp. v. CA, 199 S 882 ..................................................... 332

Section 14 ................................................................................................. 339

Uy v. CA, 191 S .................................................................................................... 339

Manila Herald Publishing v. Ramos, 88 Phil. 94 ............................................. 345

Traders Royal Bank v. IAC, 133 S 141 ................................................................ 349

Ching v. CA, 423 S 356 ....................................................................................... 353

Section 15 ................................................................................................ 360

Tayabas Land v. Sharruf, 41 Phil. 382 (See under Section 7 page 235) .......... 360

Bilag-Rivera v. Flora, July 6, 1995 ..................................................................... 360

PNB v. Vasquez, 71 Phil. 433 ..............................................................................365

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

3 of 501

PAL v. CA, 181 S 557........................................................................................... 367

Section 17 .................................................................................................385

Luzon Steel v. Sia, 28 S 58 .................................................................................385

Phil. British Assurance Co. v. IAC, 150 S 520 .................................................. 389

The Imperial Insurance v. de los Angeles, 111 S 25 ........................................... 393

Vadil v. de Venecia, 9 S 374 .............................................................................. 399

Zaragoza v. Fidelino, 163 S 443 ........................................................................ 402

Dizon v. Valdez, 23 S 200 ................................................................................. 406

Pioneer Insurance v. Camilon, 116 S 190 .......................................................... 408

UPPC v. Acropolis, January 25, 2012 ................................................................. 410

Section 20 ................................................................................................ 416

Calderon v. IAC, 155 S 531 (See under Section 4 page 134) ............................... 416

Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corp. v. Hontanosas, 78 S 447 ........................ 416

Stronghold Insurance v. CA, November 6, 1989 ............................................. 428

Carlos v. Sandoval, 471 S 266 (See under Section 3 page 112) .......................... 432

Maningo v. IAC, 183 S 691 .................................................................................. 433

Santos v. CA, 95 Phil. 360 ................................................................................. 439

Aquino v. Socorro, 35 S 373 .............................................................................. 442

Hanil Development v. IAC, 144 S 557 ............................................................... 445

BA Finance v. CA, 161 S 608 ............................................................................... 451

Malayan Insurance v. Salas, 90 S 252 .............................................................. 456

Philippine Charter Insurance v. CA, 179 S 468................................................ 464

Zaragoza v. Fidelino, 163 S 443 (See under Section 17 page 402) ................... 469

Zenith Insurance v. CA, 119 S 485 .................................................................... 469

Lazatin v. Twano, 2 S 842 ..................................................................................473

MC Engineering v. CA, 380 S 116 ...................................................................... 477

DM Wenceslao v. Readycon Trading & Const. Corp., 433 S 251 ..................... 491

Sps Yu v. Ngo Yet Te, February 6, 2007 ........................................................... 496

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

4 of 501

Section 1

Calo v. Roldan, 76 Phil. 445

G.R. No. L-252 March 30, 1946

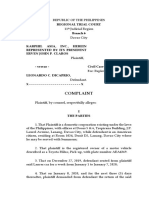

TRANQUILINO CALO and DOROTEO SAN JOSE, petitioners,

vs.

ARSENIO C. ROLDAN, Judge of First Instance of Laguna, REGINO

RELOVA and TEODULA BARTOLOME,respondents.

Zosimo D. Tanalega for petitioners.

Estanislao A. Fernandez for respondents Relova and Bartolome.

No appearance for respondent Judge.

FERIA, J.:

This is a petition for writ of certiorari against the respondent Judge Arsenio C.

Roldan of the Court First Instance of Laguna, on the ground that the latter has

exceeded his jurisdiction or acted with grave abuse of discretion in appointing

a receiver of certain lands and their fruits which, according to the complainant

filed by the other respondents, as plaintiffs, against petitioners, as defendants,

in case No. 7951, were in the actual possession of and belong to said plaintiffs.

The complaint filed by plaintiffs and respondents against defendants and

petitioners in the Court of First Instance of Laguna reads as follows:

1. That the plaintiffs and the defendants are all of legal age, Filipino

citizens, and residents of Pila, Laguna; the plaintiffs are husband and

wife..

2. That the plaintiff spouses are the owners and the possessors of the

following described parcels of land, to wit:.

x x x x x x x x x

3. That parcel No. (a) described above is now an unplanted rice land

and parcel No. (b) described in the complaint is a coconut land, both

under the possession of the plaintiffs..

4. That the defendants, without any legal right whatsoever and in

connivance with each other, through the use of force, stealth, threats

and intimidation, intend or are intending to enter and work or harvest

whatever existing fruits may now be found in the lands above-

mentioned in violation of plaintiff's in this case ineffectual..

5. That unless defendants are barred, restrained, enjoined, and

prohibited from entering or harvesting the lands or working therein

through ex-parte injunction, the plaintiffs will suffer injustice,

damages and irreparable injury to their great prejudice..

6. That the plaintiffs are offering a bond in their application for ex-

parte injunction in the amount of P2,000, subject to the approval of

this Hon. Court, which bond is attached hereto marked as Annex A

and made an integral part of this complaint..

7. That on or about June 26, 1945, the defendants, through force,

destroyed and took away the madre-cacao fencer, and barbed wires

built on the northwestern portion of the land designated as parcel No.

(b) of this complaint to the damage and prejudice of the plaintiffs in

the amount of at least P200..

Wherefore, it is respectfully prayed:.

(a) That the accompanying bond in the amount of P2,000 be

approved;

(b) That a writ of preliminary injunction be issued ex-

parte immediately restraining, enjoining and prohibiting the

defendants, their agents, servants, representatives, attorneys, and, (or)

other persons acting for and in their behalf, from entering in,

interfering with and/or in any wise taking any participation in the

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

5 of 501

harvest of the lands belonging to the plaintiffs; or in any wise working

the lands above-described;

(c) That judgment be rendered, after due hearing, declaring the

preliminary injunction final;.

(d) That the defendants be condemned jointly and severally to pay the

plaintiffs the sum of P200 as damages; and.

(e) That plaintiffs be given such other and further relief just and

equitable with costs of suit to the defendants.

The defendants filed an opposition dated August 8, 1945, to the issuance of the

writ of preliminary injunction prayed for in the above-quoted complaint, on

the ground that they are owners of the lands and have been in actual

possession thereof since the year 1925; and their answer to the complaint filed

on August 14, 1945, they reiterate that they are the owners and were then in

actual possession of said property, and that the plaintiffs have never been in

possession thereof.

The hearing of the petition for preliminary injunction was held on August 9,

1945, at which evidence was introduced by both parties. After the hearing,

Judge Rilloraza, then presiding over the Court of First Instance of Laguna,

denied the petition on the ground that the defendants were in actual

possession of said lands. A motion for reconsideration was filed by plaintiffs on

August 20, 1945, but said motion had not yet, up to the hearing of the present

case, been decided either by Judge Rilloraza, who was assigned to another

court, or by the respondent judge.

The plaintiffs (respondents) filed on September 4, 1945, a reply to defendants'

answer in which, among others, they reiterate their allegation in the complaint

that they are possessors in good faith of the properties in question.

And on December 17, plaintiffs filed an urgent petition ex-parte praying that

plaintiffs' motion for reconsideration of the order denying their petition for

preliminary injunction be granted and or for the appointment of a receiver of

the properties described in the complaint, on the ground that (a) the plaintiffs

have an interest in the properties in question, and the fruits thereof were in

danger of being lost unless a receiver was appointed; and that (b) the

appointment of a receiver was the most convenient and feasible means of

preserving, administering and or disposing of the properties in litigation which

included their fruits. Respondents Judge Roldan, on the same date, December

17, 1945, decided that the court would consider the motion for reconsideration

in due time, and granted the petition for appointment of and appointed a

receiver in the case.

The question to be determined in the present special civil action

of certiorari is, whether or not the respondent judge acted in excess of his

jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion in issuing the order appointing a

receiver in the case No. 7951 of the Court of First Instance of Laguna; for it is

evident that there is no appeal or any other plain, speedy, and adequate

remedy in the ordinary course of the law against the said order, which is an

incidental or interlocutory one.

It is a truism in legal procedure that what determines the nature of an action

filed in the courts are the facts alleged in the complaint as constituting the

cause of the action. The facts averred as a defense in the defendant's answer do

not and can not determine or change the nature of the plaintiff's action. The

theory adopted by the plaintiff in his complaint is one thing, and that of the

defendant in his answer is another. The plaintiff has to establish or prove his

theory or cause of action in order to obtain the remedy he prays for; and the

defendant his theory, if necessary, in order to defeat the claim or action of the

plaintiff..

According to the complaint filed in the said case No. 7951, the plaintiff's action

is one of ordinary injunction, for the plaintiffs allege that they are the owners

of the lands therein described, and were in actual possession thereof, and that

"the defendants without any legal right whatever and in connivance with each

other, through the use of force, stealth, threat and intimidation, intend or are

intending to enter and work or harvest whatever existing fruits may be found

in the lands above mentioned in violation of plaintiffs' proprietary rights

thereto;" and prays "that the defendants, their agents, servants,

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

6 of 501

representatives, and other persons acting for or in their behalf, be restrained,

enjoined and prohibited from entering in, interfering with, or in any way

taking any participation in the harvest of the lands above describe belonging

to the plaintiffs."

That this is the nature of plaintiffs' action corroborated by the fact that they

petitioned in the same complaint for a preliminary prohibitory injunction,

which was denied by the court in its order dated August 17, 1945, and that the

plaintiffs, in their motion for reconsideration of said order filed on August 20

of the same year, and in their urgent petition dated December 17, moving the

court to grant said motion for reconsideration, reiterated that they were actual

possessors of the land in question.

The fact that plaintiffs, in their reply dated September 4, after reiterating their

allegation or claim that they are the owners in fee simple and possessors in

good faith of the properties in question, pray that they be declared the owners

in fee simple, has not changed the nature of the action alleged in the

complaint or added a new cause of action thereto; because the allegations in

plaintiffs' reply were in answer to defendants' defenses, and the nature of

plaintiffs' cause of action, as set forth in their complaint, was not and could

not be amended or changed by the reply, which plaintiffs had the right to

present as a matter of course. A plaintiff can not, after defendant's answer,

amend his complaint by changing the cause of action or adding a new one

without previously obtaining leave of court (section 2, Rule 17)..

Respondents' contention in paragraph I of their answer that the action filed by

them against petitioners in the case No. 7951 of the Court of First Instance of

Laguna is not only for injunction, but also to quiet title over the two parcels of

land described in the complaint, is untenable for the reasons stated in the

previous paragraph. Besides, an equitable action to quiet title, in order to

prevent harrassment by continued assertion of adverse title, or to protect the

plaintiff's legal title and possession, may be filed in courts of equity (and our

courts are also of equity), only where no other remedy at law exists or where

the legal remedy invokable would not afford adequate remedy (32 Cyc., 1306,

1307). In the present case wherein plaintiffs alleged that they are the owners

and were in actual possession of the lands described in the complaint and

their fruits, the action of injunction filed by them is the proper and adequate

remedy in law, for a judgment in favor of plaintiffs would quiet their title to

said lands..

The provisional remedies denominated attachment, preliminary injunction,

receivership, and delivery of personal property, provided in Rules 59, 60, 61,

and 62 of the Rules of Court, respectively, are remedies to which parties

litigant may resort for the preservation or protection of their rights or interest,

and for no other purpose, during the pendency of the principal action. If an

action, by its nature, does not require such protection or preservation, said

remedies can not be applied for and granted. To each kind of action or actions

a proper provisional remedy is provided for by law. The Rules of Court clearly

specify the case in which they may be properly granted. .

Attachment may be issued only in the case or actions specifically stated in

section 1, Rule 59, in order that the defendant may not dispose of his property

attached, and thus secure the satisfaction of any judgment that may be

recovered by plaintiff from defendant. For that reason a property subject of

litigation between the parties, or claimed by plaintiff as his, can not be

attached upon motion of the same plaintiff..

The special remedy of preliminary prohibitory injunction lies when the

plaintiff's principal action is an ordinary action of injunction, that is, when the

relief demanded in the plaintiff's complaint consists in restraining the

commission or continuance of the act complained of, either perpetually or for

a limited period, and the other conditions required by section 3 of Rule 60 are

present. The purpose of this provisional remedy is to preserve the status quo of

the things subject of the action or the relation between the parties, in order to

protect the rights of the plaintiff respecting the subject of the action during

the pendency of the suit. Because, otherwise or if no preliminary prohibition

injunction were issued, the defendant may, before final judgment, do or

continue the doing of the act which the plaintiff asks the court to restrain, and

thus make ineffectual the final judgment rendered afterwards granting the

relief sought by the plaintiff. But, as this court has repeatedly held, a writ of

preliminary injunction should not be granted to take the property out of the

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

7 of 501

possession of one party to place it in the hands of another whose title has not

been clearly established..

A receiver may be appointed to take charge of personal or real property which

is the subject of an ordinary civil action, when it appears that the party

applying for the appointment of a receiver has an interest in the property or

fund which is the subject of the action or litigation, and that such property or

fund is in danger of being lost, removed or materially injured unless a receiver

is appointed to guard and preserve it (section 1 [b], Rule 61); or when it appears

that the appointment of a receiver is the most convenient and feasible means

of preserving, administering or disposing of the property in litigation (section 1

[e] of said Rule). The property or fund must, therefore be in litigation

according to the allegations of the complaint, and the object of appointing a

receiver is to secure and preserve the property or thing in controversy pending

the litigation. Of course, if it is not in litigation and is in actual possession of

the plaintiff, the latter can not apply for and obtain the appointment of a

receiver thereof, for there would be no reason for such appointment.

Delivery of personal property as a provisional remedy consists in the delivery,

by order of the court, of a personal property by the defendant to the plaintiff,

who shall give a bond to assure the return thereof or the payment of damages

to the defendant in the plaintiff's action to recover possession of the same

property fails, in order to protect the plaintiff's right of possession of said

property, or prevent the defendant from damaging, destroying or disposing of

the same during the pendency of the suit.

Undoubtedly, according to law, the provisional remedy proper to plaintiffs'

action of injunction is a preliminary prohibitory injunction, if plaintiff's

theory, as set forth in the complaint, that he is the owner and in actual

possession of the premises is correct. But as the lower court found at the

hearing of the said petition for preliminary injunction that the defendants

were in possession of the lands, the lower court acted in accordance with law

in denying the petition, although their motion for reconsideration, which was

still pending at the time the petition in the present case was heard in this

court, plaintiffs insist that they are in actual possession of the lands and,

therefore, of the fruits thereof.

From the foregoing it appears evident that the respondent judge acted in

excess of his jurisdiction in appointing a receiver in case No. 7951 of the Court

of First Instance of Laguna. Appointment of a receiver is not proper or does

not lie in an action of injunction such as the one filed by the plaintiff. The

petition for appointment of a receiver filed by the plaintiffs (Exhibit I of the

petition) is based on the ground that it is the most convenient and feasible

means of preserving, administering and disposing of the properties in

litigation; and according to plaintiffs' theory or allegations in their complaint,

neither the lands nor the palay harvested therein, are in litigation. The

litigation or issue raised by plaintiffs in their complaint is not the ownership or

possession of the lands and their fruits. It is whether or not defendants intend

or were intending to enter or work or harvest whatever existing fruits could

then be found in the lands described in the complaint, alleged to be the

exclusive property and in the actual possession of the plaintiffs. It is a matter

not only of law but of plain common sense that a plaintiff will not and legally

can not ask for the appointment or receiver of property which he alleges to

belong to him and to be actually in his possession. For the owner and

possessor of a property is more interested than persons in preserving and

administering it.

Besides, even if the plaintiffs had amended their complaint and alleged that

the lands and palay harvested therein are being claimed by the defendants,

and consequently the ownership and possession thereof were in litigation, it

appearing that the defendants (now petitioners) were in possession of the

lands and had planted the crop or palay harvested therein, as alleged in

paragraph 6 (a) and (b) of the petition filed in this court and not denied by the

respondent in paragraph 2 of his answer, the respondent judge would have

acted in excess of his jurisdiction or with a grave abuse of discretion in

appointing a receiver thereof. Because relief by way of receivership is equitable

in nature, and a court of equity will not ordinarily appoint a receiver where the

rights of the parties depend on the determination of adverse claims of legal

title to real property and one party is in possession (53 C. J., p. 26). The present

case falls within this rule..

In the case of Mendoza vs. Arellano and B. de Arellano, this court said:

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

8 of 501

Appointments of receivers of real estate in cases of this kind lie largely

in the sound discretion of the court, and where the effect of such an

appointment is to take real estate out of the possession of the

defendant before the final adjudication of the rights of the parties, the

appointment should be made only in extreme cases and on a clear

showing of necessity therefor in order to save the plaintiff from grave

and irremediable loss or damage. (34 Cyc., 51, and cases there cited.)

No such showing has been made in this case as would justify us in

interfering with the exercise by trial judge of his discretion in denying

the application for receiver. (36 Phil., 59, 63, 64.).

Although the petition is silent on the matter, as the respondents in their

answer allege that the Court of First Instance of Laguna has appointed a

receiver in another case No. 7989 of said court, instituted by the respondents

Relova against Roberto Calo and his brothers and sisters, children of Sofia de

Oca and Tranquilino Calo (petitioner in this case), and submitted copy of the

complaint filed by the plaintiffs (now respondents) in case No. 7989 (Exhibit 9

of the respondents' answer), we may properly express and do hereby express

here our opinion, in order to avoid multiplicity of suits, that as the cause of

action alleged in the in the complaint filed by the respondents Relova in the

other case is substantially the same as the cause of action averred in the

complaint filed in the present case, the order of the Court of First Instance of

Laguna appointing a receiver in said case No. 7989 was issued in excess of its

jurisdiction, and is therefore null and void.

In view of all the foregoing, we hold that the respondent Judge Arsenio C.

Roldan of the Court of First Instance of Laguna has exceeded his jurisdiction in

appointing a receiver in the present case, and therefore the order of said

respondent judge appointing the receiver, as well as all other orders and

proceedings of the court presided over by said judge in connection with the

receivership, are null and void.

As to the petitioners' petition that respondents Relova be punished for

contempt of court for having disobeyed the injunction issued by this court

against the respondents requiring them to desist and refrain from enforcing

the order of receivership and entering the palay therein, it appearing from the

evidence in the record that the palay was harvested by the receiver and not by

said respondents, the petition for contempt of court is denied. So ordered,

with costs against the respondents.

Moran, C. J., Ozaeta, Jaranilla, De Joya, Pablo, Perfecto, Hilado, and Bengzon,

JJ., concur.

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

9 of 501

KO Glass v. Valenzuela, 116 S 563

G.R. No. L-48756 September 11, 1982

K.O. GLASS CONSTRUCTION CO., INC., petitioner,

vs.

THE HONORABLE MANUEL VALENZUELA, Judge of the Court of First

Instance of Rizal, and ANTONIO D. PINZON, respondents.

Guillermo E. Aragones for petitioner.

Ruben V. Lopez for respondent Antonio D. Pinzon.

CONCEPCION, JR., J.:

Petition for certiorari to annul and set aside the writ of preliminary

attachment issued by the respondent Judge in Civil Case No. 5902-P of the

Court of First Instance of Rizal, entitled: Antonio D. Pinzon plaintiff, versus

K.O. Glass Construction Co., Inc., and Kenneth O. Glass, defendants, and for

the release of the amount of P37,190.00, which had been deposited with the

Clerk of Court, to the petitioner.

On October 6, 1977, an action was instituted in the Court of First Instance of

Rizal by Antonio D. Pinzon to recover from Kenneth O. Glass the sum of

P37,190.00, alleged to be the agreed rentals of his truck, as well as the value of

spare parts which have not been returned to him upon termination of the

lease. In his verified complaint, the plaintiff asked for an attachment against

the property of the defendant consisting of collectibles and payables with the

Philippine Geothermal, Inc., on the grounds that the defendant is a foreigner;

that he has sufficient cause of action against the said defendant; and that there

is no sufficient security for his claim against the defendant in the event a

judgment is rendered in his favor.

1

Finding the petition to be sufficient in form and substance, the respondent

Judge ordered the issuance of a writ of attachment against the properties of

the defendant upon the plaintiff's filing of a bond in the amount of

P37,190.00.

2

Thereupon, on November 22, 1977, the defendant Kenneth O. Glass moved to

quash the writ of attachment on the grounds that there is no cause of action

against him since the transactions or claims of the plaintiff were entered into

by and between the plaintiff and the K.O. Glass Construction Co., Inc., a

corporation duly organized and existing under Philippine laws; that there is no

ground for the issuance of the writ of preliminary attachment as defendant

Kenneth O. Glass never intended to leave the Philippines, and even if he does,

plaintiff can not be prejudiced thereby because his claims are against a

corporation which has sufficient funds and property to satisfy his claim; and

that the money being garnished belongs to the K.O. Glass Corporation Co.,

Inc. and not to defendant Kenneth O. Glass.

3

By reason thereof, Pinzon amended his complaint to include K.O. Glass

Construction Co., Inc. as co-defendant of Kenneth O. Glass.

4

On January 26, 1978, the defendants therein filed a supplementary motion to

discharge and/or dissolve the writ of preliminary attachment upon the ground

that the affidavit filed in support of the motion for preliminary attachment

was not sufficient or wanting in law for the reason that: (1) the affidavit did not

state that the amount of plaintiff's claim was above all legal set-offs or

counterclaims, as required by Sec. 3, Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court; (2)

the affidavit did not state that there is no other sufficient security for the claim

sought to be recovered by the action as also required by said Sec. 3; and (3) the

affidavit did not specify any of the grounds enumerated in Sec. 1 of Rule

57,

5

but, the respondent Judge denied the motion and ordered the Philippine

Geothermal, Inc. to deliver and deposit with the Clerk of Court the amount of

P37,190.00 immediately upon receipt of the order which amount shall remain

so deposited to await the judgment to be rendered in the case.

6

On June 19, 1978, the defendants therein filed a bond in the amount of

P37,190.00 and asked the court for the release of the same amount deposited

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

10 of 501

with the Clerk of Court,

7

but, the respondent Judge did not order the release

of the money deposited.

8

Hence, the present recourse. As prayed for, the Court issued a temporary

restraining order, restraining the respondent Judge from further proceeding

with the trial of the case.

9

We find merit in the petition. The respondent Judge gravely abused his

discretion in issuing the writ of preliminary attachment and in not ordering

the release of the money which had been deposited with the Clerk of Court for

the following reasons:

First, there was no ground for the issuance of the writ of preliminary

attachment. Section 1, Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court, which

enumerates the grounds for the issuance of a writ of preliminary attachment,

reads, as follows:

Sec. 1. Grounds upon which attachment may issue. A

plaintiff or any proper party may, at the commencement of

the action or at any time thereafter, have the property of the

adverse party attached as security for the satisfaction of any

judgment that may be recovered in the following cases:

(a) In an action for the recovery of money or damages on a

cause of action arising from contract, express or implied,

against a party who is about to depart from the Philippines

with intent to defraud his creditor;

(b) In an action for money or property embezzled or

fraudulently misapplied or converted to his own use by a

public officer, or an officer of a corporation, or an attorney,

factor, broker, agent, or clerk, in the course of his

employment as such, or by any other person in a fiduciary

capacity, or for a willful violation of duty;

(c) In an action to recover the possession of personal property

unjustly detained, when the property, or any part thereof, has

been concealed, removed, or disposed of to prevent its being

found or taken by the applicant or an officer;

(d) In an action against the party who has been guilty of a

fraud in contracting the debt or incurring the obligation upon

which the action is brought, or in concealing or disposing of

the property for the taking, detention or conversion of which

the action is brought;

(e) In an action against a party who has removed or disposed

of his property, or is about to do so, with intent to defraud his

creditors;

(f) In an action against a party who resides out of the

Philippines, or on whom summons may be served by

publication.

In ordering the issuance of the controversial writ of preliminary attachment,

the respondent Judge said and We quote:

The plaintiff filed a complaint for a sum of money with prayer

for Writ of Preliminary Attachment dated September 14, 1977,

alleging that the defendant who is a foreigner may, at any

time, depart from the Philippines with intent to defraud his

creditors including the plaintiff herein; that there is no

sufficient security for the claim sought to be enforced by this

action; that the amount due the plaintiff is as much as the

sum for which an order of attachment is sought to be granted;

and that defendant has sufficient leviable assets in the

Philippines consisting of collectibles and payables due from

Philippine Geothermal, Inc., which may be disposed of at any

time, by defendant if no Writ of Preliminary Attachment may

be issued. Finding said motion and petition to be sufficient in

form and substance.

10

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

11 of 501

Pinzon however, did not allege that the defendant Kenneth O. Glass "is a

foreigner (who) may, at any time, depart from the Philippines with intent to

defraud his creditors including the plaintiff." He merely stated that the

defendant Kenneth O. Glass is a foreigner. The pertinent portion of the

complaint reads, as follows:

15. Plaintiff hereby avers under oath that defendant is a

foreigner and that said defendant has a valid and just

obligation to plaintiff in the total sum of P32,290.00 arising

out from his failure to pay (i) service charges for the hauling

of construction materials; (ii) rentals for the lease of plaintiff's

Isuzu Cargo truck, and (iii) total cost of the missing/destroyed

spare parts of said leased unit; hence, a sufficient cause of

action exists against saiddefendant. Plaintiff also avers under

oath that there is no sufficient security for his claim against

the defendantin the event a judgment be rendered in favor of

the plaintiff. however, defendant has sufficient assets in the

Philippines in the form of collectible and payables due from

the Philippine Geothermal, Inc. with office address at

Citibank Center, Paseo de Roxas, Makati, Metro Manila, but

which properties, if not timely attached, may be disposed of

by defendants and would render ineffectual the reliefs prayed

for by plaintiff in this Complaint.

11

In his Amended Complaint, Pinzon alleged the following:

15. Plaintiff hereby avers under oath that defendant GLASS is

an American citizen who controls most, if not all, the affairs

of defendant CORPORATION. Defendants CORPORATION

and GLASS have a valid and just obligation to plaintiff in the

total sum of P32,290.00 arising out for their failure to pay (i)

service charges for hauling of construction materials, (ii)

rentals for the lease of plaintiff's Isuzu Cargo truck, and (iii)

total cost of the missing/destroyed spare parts of said leased

unit: hence, a sufficient cause of action exist against

saiddefendants. Plaintiff also avers under oath that there is no

sufficient security for his claim against thedefendants in the

event a judgment be rendered in favor of the plaintiff.

however, defendant CORPORATION has sufficient assets in

the Philippines in the form of collectibles and payables due

from the Philippine Geothermal., Inc. with office address at

Citibank Center, Paseo de Roxas, Makati, Metro Manila, but

which properties, if not timely attached, may be disposed of

by defendants and would render ineffectual the reliefs prayed

for by plaintiff in this Complaint.

12

There being no showing, much less an allegation, that the defendants are

about to depart from the Philippines with intent to defraud their creditor, or

that they are non-resident aliens, the attachment of their properties is not

justified.

Second, the affidavit submitted by Pinzon does not comply with the Rules.

Under the Rules, an affidavit for attachment must state that (a) sufficient

cause of action exists, (b) the case is one of those mentioned in Section I (a) of

Rule 57; (c) there is no other sufficient security 'or the claim sought to be

enforced by the action, and (d) the amount due to the applicant for

attachment or the value of the property the possession of which he is entitled

to recover, is as much as the sum for which the order is granted above all legal

counterclaims. Section 3, Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court reads. as

follows:

Section 3. Affidavit and bond required.An order of

attachment shall be granted only when it is made to appear

by the affidavit of the applicant, or of some person who

personally knows the facts, that a sufficient cause of action

exists that the case is one of those mentioned in Section 1

hereof; that there is no other sufficient security for the claim

sought to be enforced by the action, and that the amount due

to the applicant, or the value of the property the possession of

which he is entitled to recover, is as much as the sum for

which the order is granted above all legal counterclaims. The

affidavit, and the bond required by the next succeeding

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

12 of 501

section, must be duly filed with the clerk or judge of the court

before the order issues.

In his affidavit, Pinzon stated the following:

I, ANTONIO D. PINZON Filipino, of legal age, married and

with residence and postal address at 1422 A. Mabini Street,

Ermita, Manila, subscribing under oath, depose and states

that.

1. On October 6,1977,I filed with the Court of First Instance of

Rizal, Pasay City Branch, a case against Kenneth O. Glass

entitled 'ANTONIO D. PINZON vs. KENNETH O. GLASS',

docketed as Civil Case No. 5902-P;

2. My Complaint against Kenneth O. Glass is based on several

causes of action, namely:

(i) On February 15, 1977, we mutually agreed that I undertake

to haul his construction materials from Manila to his

construction project in Bulalo, Bay, Laguna and vice-versa, for

a consideration of P50.00 per hour;

(ii) Also, on June 18, 1977, we entered into a separate

agreement whereby my Isuzu cargo truck will be leased to

him for a consideration of P4,000.00 a month payable on the

15th day of each month;

(iii) On September 7, 1977, after making use of my Isuzu

truck, he surrendered the same without paying the monthly

rentals for the leased Isuzu truck and the peso equivalent of

the spare parts that were either destroyed or misappropriated

by him;

3. As of today, October 11, 1977, Mr. Kenneth 0. Glass still owes

me the total sum of P32,290.00 representing his obligation

arising from the hauling of his construction materials,

monthly rentals for the lease Isuzu truck and the peso

equivalent of the spare parts that were either destroyed or

misappropriated by him;

4. I am executing this Affidavit to attest to the truthfulness of

the foregoing and in compliance with the provisions of Rule

57 of the Revised Rules of Court.

13

While Pinzon may have stated in his affidavit that a sufficient cause of action

exists against the defendant Kenneth O. Glass, he did not state therein that

"the case is one of those mentioned in Section 1 hereof; that there is no other

sufficient security for the claim sought to be enforced by the action; and that

the amount due to the applicant is as much as the sum for which the order

granted above all legal counter-claims." It has been held that the failure to

allege in the affidavit the requisites prescribed for the issuance of a writ of

preliminary attachment, renders the writ of preliminary attachment issued

against the property of the defendant fatally defective, and the judge issuing it

is deemed to have acted in excess of his jurisdiction.

14

Finally, it appears that the petitioner has filed a counterbond in the amount of

P37,190.00 to answer for any judgment that may be rendered against the

defendant. Upon receipt of the counter-bond the respondent Judge should

have discharged the attachment pursuant to Section 12, Rule 57 of the Revised

Rules of Court which reads, as follows:

Section 12. Discharge of attachment upon giving

counterbond.At any time after an order of attachment has

been granted, the party whose property has been attached, or

the person appearing on his behalf, may upon reasonable

notice to the applicant, apply to the judge who granted the

order, or to the judge of the court in which the action is

pending, for an order discharging the attachment wholly or in

part on the security given. The judge shall, after hearing,

order the discharge of the attachment if a cash deposit is

made or a counterbond executed to the attaching creditor is

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

13 of 501

filed, on behalf of the adverse party, with the clerk or judge of

the court where the application is made, in an amount equal

to the value of the property attached as determined by the

judge, to secure the payment of any judgment that the

attaching creditor may recover in the action. Upon the filing

of such counter-bond, copy thereof shall forthwith be served

on the attaching creditor or his lawyer. Upon the discharge of

an attachment in accordance with the provisions of this

section the property attached, or the proceeds of any sale

thereof, shall be delivered to the party making the deposit or

giving the counter-bond, or the person appearing on his

behalf, the deposit or counter-bond aforesaid standing in the

place of the property so released. Should such counter-bond

for any reason be found to be, or become, insufficient, and the

party furnishing the same fail to file an additional counter-

bond the attaching creditor may apply for a new order of

attachment.

The filing of the counter-bond will serve the purpose of preserving the

defendant's property and at the same time give the plaintiff security for any

judgment that may be obtained against the defendant.

15

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED and the writ prayed for is issued. The

orders issued by the respondent Judge on October 11, 19719, January 26, 1978,

and February 3, 1978 in Civil Case No. 5902-P of the Court of First Instance of

Rizal, insofar as they relate to the issuance of the writ of preliminary

attachment, should be as they are hereby ANNULLED and SET ASIDE and the

respondents are hereby ordered to forthwith release the garnished amount of

P37,190.00 to the petitioner. The temporary restraining order, heretofore

issued, is hereby lifted and set aside. Costs against the private respondent

Antonio D. Pinzon.

SO ORDERED.

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

14 of 501

General v. De Venecia, 78 Phil. 780, July 30, 1947

G.R. No. L-894

LUIS F. GENERAL, petitioner,

vs.

JOSE R. DE VENECIA, Judge of First Instance of Camarines Sur, and

PETRA VDA. DE RUEDAS, also representing Ernesto, Armando and

Gracia (minors), respondents.

Cea, Blancaflor and Cea for petitioner.

Jose M. Peas for respondents Ruedas.

Bengzon (Jose), J.:

Petition for certiorari to annul the order of the Court of First Instance of

Camarines Sur denying the motion to dismiss the complaint, and to vacate the

attachment issued, in civil case No. 364 therein entitled, Ruedas vs. Luis F.

General.

That complaint was filed on June 4, 1946, to recover the value of a promissory

note, worded as follows:

For value received, I promise to pay Mr. Gregorio Ruedas the amount of four

thousand pesos (P4,000), in Philippine currency within six (6) months after

peace has been declared and government established in the Philippines.

Naga, Camarines Sur, September 25, 1944.

(Sgd.) LUIS F. GENERAL

It prayed additionally for preliminary attachment of defendants property,

upon the allegation that the latter was about to dispose of his assets to defraud

creditors. Two days later, the writ of attachment was issued upon the filing of

a suitable bond.

Having been served with summons, the defendant therein, Luis F. General,

submitted, on June 11, 1946, a motion praying for dismissal of the complaint

and dissolution of the attachment. He claimed it was premature, in view of the

provisions of the debt moratorium orders of the President of the Philippines

(Executive Orders Nos. 25 and 32 of 1945). Denial of this motion and of the

subsequent plea for reconsideration, prompted the institution of this special

civil action, which we find to be meritorious, for the reason that the

attachment was improvidently permitted, the debt being within the terms of

the decree of moratorium (Executive Order No. 32).

It is our view that, upon objection by the debtor, no court may now proceed to

hear a complaint that seeks to compel payment of a monetary obligation

coming within the purview of the moratorium. And the issuance of a writ of

attachment upon such complaint may not, of course, be allowed. Such levy is

necessarily one step in the enforcement of the obligation, enforcement which,

as stated in the order, is suspended temporarily, pending action by the

Government.

But the case for petitioner is stronger when we reflect that his promise is to

pay P4,000 within six months after peace has been declared. It being a

matter of contemporary history that the peace treaty between the United

States and Japan has not even been drafted, and that no competent official has

formally declared the advent of peace (see Raquiza vs. Bardford, 75 Phil. 50), it

is obvious that the six-month period has not begun; and Luis F. General has at

present and in June, 1946, no demandable duty to make payment to plaintiffs,

independently of the moratorium directive.

On the question of validity of the attachment, the general rule is that, unless

the statute expressly so provides, the remedy by attachment is not available in

respect to a demand which is not due and payable, and if an attachment is

issued upon such a demand without statutory authority it is void. (7 C.J.S., p.

204.)

It must be observed that under our rules governing the matter the person

seeking a preliminary attachment must show that a sufficient cause of action

exists and that the amount due him is as much as the sum for which the order

of attachment is granted (sec. 3, Rule 59). Inasmuch as the commitment of

Luis F. General has not as yet become demandable, there existed no cause of

action against him, and the complaint should have been dismissed and the

attachment lifted. (Orbeta vs. Sotto, 58 Phil. 505.)

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

15 of 501

And although it is the general principle that certiorari is not available to

correct judicial errors that could be straightened out in an appeal, we have

adopted the course that where an attachment has been wrongly levied the writ

may be applied for, because the remedy by appeal is either unavailable or

inadequate. (Leung Ben vs. OBrien, 38 Phil. 182; Director of Commerce and

Industry vs. Concepcion, 43 Phil. 384; Orbeta vs. Sotto, supra.)

Wherefore, the writ of attachment is quashed and the complaint is dismissed.

Costs for petitioner. So ordered.

Moran, C.J., Paras, Feria, Pablo, Hilado, Padilla, and Tuason, JJ., concur.

Perfecto, J., concurs in the result.

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

16 of 501

Miailhe v. De Lencquesaing, 142 S 694

G.R. No. L-67715 July 11, 1986

WILLIAM ALAIN MIAILHE and THE HON. FELIX V. BARBERS, in his

capacity as Presiding Judge, RTC of Manila, Branch XXXIII, petitioners-

appellants,

vs.

ELAINE M. DE LENCQUESAING and HERVE DE

LENCQUESAING, respondents-appellees.

PARAS, J.:

This petition is an appeal by certiorari from the Decision of the Intermediate

Appellate Court in AC-G.R. SP. No. 01914 which declared null-and void, the

Order of the Hon. Judge Felix V. Barbers, issued in Civil Case No. 83-16829,

dated April 14, 1983, granting petitioner's application for the issuance of a writ

of preliminary attachment and the Order dated September 13, 1983 denying

respondent's motion to lift said attachment.

The pertinent facts that gave rise to the instant petition are as follows:

Petitioner William Alain Miailhe, his sisters Monique Miailhe Sichere, Elaine

Miailhe de Lencquesaing and their mother, Madame Victoria D. Miailhe are

co-owners of several registered real properties located in Metro Manila. By

common consent of the said co-owners, petitioner William Alain has been

administering said properties since 1960. As Madame Victoria D. Miailhe, her

daughter Monique and son William Alain (herein petitioner) failed to secure

an out-of court partition thereof due to the unwillingness or opposition of

respondent Elaine, they filed in the Court of First Instance of Manila (now

Regional Trial Court) an action for Partition, which was docketed as Civil Case

No. 105774 and assigned to Branch . . . thereof, presided over by Judge Pedro

Ramirez. Among the issues presented in the partition case was the matter of

petitioner's account as administrator of the properties sought to be

partitioned. But while the said administrator's account was still being

examined, respondent Elaine filed a motion praying that the sum of

P203,167.36 which allegedly appeared as a cash balance in her favor as of

December 31, 1982, be ordered delivered to her by petitioner William Alain.

Against the opposition of petitioner and the other co-owners, Judge Pedro

Ramirez granted the motion in his Order dated December 19, 1983 which order

is now the subject of a certiorari proceeding in the Intermediate Appellate

Court under AC-G.R. No. SP-03070.

Meanwhile however, and more specifically on February 28, 1983, respondent

Elaine filed a criminal complaint for estafa against petitioner William Alain,

with the office of the City Fiscal of Manila, alleging in her supporting affidavit

that on the face of the very account submitted by him as Administrator, he

had misappropriated considerable amounts, which should have been turned

over to her as her share in the net rentals of the common properties. Two days

after filing the complaint, respondent flew back to Paris, the City of her

residence. Likewise, a few days after the filing of the criminal complaint, an

extensive news item about it appeared prominently in the Bulletin Today,

March 4, 1983 issue, stating substantially that Alain Miailhe, a consul of the

Philippines in the Republic of France, had been charged with Estafa of several

million pesos by his own sister with the office of the City Fiscal of Manila.

On April 12, 1983, petitioner Alain filed a verified complaint against respondent

Elaine, for Damages in the amount of P2,000,000.00 and attorney's fees of

P250,000.00 allegedly sustained by him by reason of the filing by respondent

(then defendant) of a criminal complaint for estafa, solely for the purpose of

embarrassing petitioner (then plaintiff) and besmirching his honor and

reputation as a private person and as an Honorary Consul of the Republic of

the Philippine's in the City of Bordeaux, France. Petitioner further charged

respondent with having caused the publication in the March 4, 1983 issue of

the Bulletin Today, of a libelous news item. In his verified complaint,

petitioner prayed for the issuance of a writ of preliminary attachment of the

properties of respondent consisting of 1/6 undivided interests in certain real

properties in the City of Manila on the ground that "respondent-defendant is a

non-resident of the Philippines", pursuant to paragraph (f), Section 1, Rule 57,

in relation to Section 17, Rule 14 of the Revised Rules of Court.

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

17 of 501

This case for Damages was docketed as Civil Case No. 83-16829 of the Regional

Trial Court of Manila, Branch XXXIII presided over by the Honorable Felix V.

Barbers.

On April 14, 1983, Judge Barbers granted petitioner's application for

preliminary attachment upon a bond to be filed by petitioner in the amount of

P2,000,000.00. Petitioner filed said bond and upon its approval, the Writ of

Preliminary Attachment was issued on April 18, 1983 which was served on the

Deputy Clerk of Court of Branch XXX before whom the action for Partition

was pending.

On May 17, 1983, respondent thru counsel filed a motion to lift or dissolve the

writ of attachment on the ground that the complaint did not comply with the

provisions of Sec. 3 of Rule 57, Rules of Court and that petitioner's claim was

for unliquidated damages. The motion to lift attachment having been denied,

respondent filed with the Intermediate Appellate Court a special action for

certiorari under AC-G.R. SP No. 01914 alleging that Judge Barbers had acted

with grave abuse of discretion in the premises. On April 4, 1984, the IAC issued

its now assailed Decision declaring null and void the aforesaid Writ of

preliminary attachment. Petitioner filed a motion for the reconsideration of

the Decision but it was denied hence, this present petition which was given

due course in the Resolution of this Court dated February 6, 1985.

We find the petition meritless. The most important issue raised by petitioner

is whether or not the Intermediate Appellate Court erred in construing Section

1 par. (f) Rule 57 of the Rules of Court to be applicable only in case the claim of

the plaintiff is for liquidated damages (and therefore not where he seeks to

recover unliquidated damages arising from a crime or tort).

In its now assailed decision, the IAC stated

We find, therefore, and so hold that respondent court had

exceeded its jurisdiction in issuing the writ of attachment on

a claim based on an action for damages arising from delict and

quasi delict the amount of which is uncertain and had not

been reduced to judgment just because the defendant is not a

resident of the Philippines. Because of the uncertainty of the

amount of plaintiff's claim it cannot be said that said claim is

over and above all legal counterclaims that defendant may

have against plaintiff, one of the indispensable requirements

for the issuance of a writ of attachment which should be

stated in the affidavit of applicant as required in Sec. 3 of Rule

57 or alleged in the verified complaint of plaintiff. The

attachment issued in the case was therefore null and void.

We agree.

Section 1 of Rule 57 of the Rules of Court provides

SEC. 1. Grounds upon which attachment may issue. A plaintiff

or any proper party may, at the commencement of the action

or at any time thereafter, have the property of the adverse

party attached as security for the satisfaction of any judgment

that may be recovered in the following cases:

(a) In an action for the recovery of money or damages on a

cause of action arising fromcontract, express or implied,

against a party who is about to depart from the Philippines

with intent to defraud his creditors;

(b) In an action for money or property embezzled or

fraudulently misapplied or converted to his own use by a

public officer, or an officer of a corporation or an attorney,

factor, broker, agent, or clerk, in the course of his

employment as such, or by any other person in a fiduciary

capacity, or for a willful violation of duty;

(c) In an action to recover the possession of personal property

unjustly detained, when the property, or any part thereof, has

been concealed. removed, or disposed of to prevent its being

found or taken by the applicant or an officer;

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

18 of 501

(d) In an action against a party who has been guilty of a fraud

in contracting the debt or incurring the obligation upon

which the action is brought, or in concealing or disposing of

the property for the taking, detention or conversion of which

the action is brought;

(e) In an action against a party who has removed or disposed

of his property, or is about to do so, with intent to defraud his

creditors;

(f) In an action against a party who resides out of the

Philippines, or on whom summons may be served by

publication. (emphasis supplied)

While it is true that from the aforequoted provision attachment may issue "in

an action against a party who resides out of the Philippines, " irrespective of the

nature of the action or suit, and while it is also true that in the case of Cu

Unjieng, et al vs. Albert, 58 Phil. 495, it was held that "each of the six grounds

treated ante is independent of the others," still it is imperative that the

amount sought be liquidated.

In view of the foregoing, the Decision appealed from is hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

19 of 501

Insular Savings Bank v. CA, 460 S 122

G.R. NO. 123638 June 15, 2005

INSULAR SAVINGS BANK, Petitioner,

vs.

COURT OF APPEALS, JUDGE OMAR U. AMIN, in his capacity as

Presiding Judge of Branch 135 of the Regional Trial Court of Makati, and

FAR EAST BANK AND TRUST COMPANY, Respondents.

D E C I S I O N

GARCIA, J.:

Thru this appeal via a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the

Rules of Court, petitioner Insular Savings Bankseeks to set aside the D E C I

S I O N

1

dated October 9, 1995 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No.

34876 and itsresolution dated January 24, 1996,

2

denying petitioners motion

for reconsideration.

The assailed decision of October 9, 1995 cleared the Regional Trial Court

(RTC) at Makati, Branch 135, of committing, as petitioner alleged, grave abuse

of discretion in denying petitioners motion to discharge attachment by

counter-bond in Civil Case No. 92-145, while the equally assailed resolution of

January 24, 1996 denied petitioners motion for reconsideration.

The undisputed facts are summarized in the appellate courts decision

3

under

review, as follows:

"On December 11, 1991, respondent Bank [Far East Bank and Trust Company]

instituted Arbitration Case No. 91-069 against petitioner [Insular Savings

Bank] before the Arbitration Committee of the Philippine Clearing House

Corporation [PCHC]. The dispute between the parties involved three

[unfunded] checks with a total value of P25,200,000.00. The checks were

drawn against respondent Bank and were presented by petitioner for clearing.

As respondent Bank returned the checks beyond the reglementary period, [but

after petitioners account with PCHC was credited with the amount of

P25,200,000.00] petitioner refused to refund the money to respondent Bank.

While the dispute was pending arbitration, on January 17, 1992, respondent

Bank instituted Civil Case No. 92-145 in the Regional Trial Court of Makati

and prayed for the issuance of a writ of preliminary attachment. On January

22, 1992, Branch 133 of the Regional Trial Court of Makati issued an Order

granting the application for preliminary attachment upon posting by

respondent Bank of an attachment bond in the amount of P6,000,000.00. On

January 27, 1992, Branch 133 of the Regional Trial Court of Makati issued a writ

of preliminary attachment for the amount of P25,200,000.00. During the

hearing on February 11, 1992 before the Arbitration Committee of the

Philippine Clearing House Corporation, petitioner and respondent Bank

agreed to temporarily divide between them the disputed amount

of P25,200,000.00 while the dispute has not yet been resolved. As a result, the

sum ofP12,600,000.00 is in the possession of respondent Bank. On March 9,

1994, petitioner filed a motion to discharge attachment by counter-bond in the

amount of P12,600,000.00. On June 13, 1994, respondent Judge issued the

first assailed order denying the motion. On June 27, 1994, petitioner

filed a motion for reconsideration which was denied in the second

assailed order dated July 20, 1994" (Emphasis and words in bracket added).

From the order denying its motion to discharge attachment by counter-bond,

petitioner went to the Court of Appeals on a petition for certiorari thereat

docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 34876, ascribing on the trial court the commission

of grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction.

While acknowledging that "[R]espondent Judge may have erred in his Order of

June 13, 1994 that the counter-bond should be in the amount of P27,237,700.00",

in that he erroneously factored in, in arriving at such amount, unliquidated

claim items, such as actual and exemplary damages, legal interest, attorneys

fees and expenses of litigation, the CA, in the herein assailed decision dated

October 9, 1995, nonetheless denied due course to and dismissed the petition.

For, according to the appellate court, the RTCs order may be defended by,

among others, the provision of Section 12 of Rule 57 of the Rules of

PROVISIONAL REMEDIES

Rule 57: Preliminary Attachment

20 of 501

Court, infra. The CA added that, assuming that the RTC erred on the matter of

computing the amount of the discharging counter-bond, its error does not

amount to grave abuse of discretion.

With its motion for reconsideration having been similarly denied, petitioner is

now with us, faulting the appellate court, as follows:

"I. THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN NOT RULING THAT THE

PRINCIPAL AMOUNT CLAIMED BY RESPONDENT BANK SHOULD

BE THE BASIS FOR COMPUTING THE AMOUNT OF THE

COUNTER-BOND, FOR THE PRELIMINARY ATTACHMENT WAS

ISSUED FOR THE SAID AMOUNT ONLY.

"II. THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN NOT RULING THAT THE

ARGUMENT THAT THE AMOUNT OF THE COUNTER-BOND

SHOULD BE BASED ON THE VALUE OF THE PROPERTY

ATTACHED CANNOT BE RAISED FOR THE FIRST TIME IN THE

COURT OF APPEALS.

"III. THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN RULING THAT THE

AMOUNT OF THE COUNTER-BOND SHOULD BE BASED ON THE

VALUE OF THE PROPERTY ATTACHED EVEN IF IT WILL RESULT

IN MAKING THE AMOUNT OF THE COUNTER-BOND EXCEED

THE AMOUNT FOR WHICH PRELIMINARY ATTACHMENT WAS

ISSUED."

Simply put, the issue is whether or not the CA erred in not ruling that the trial

court committed grave abuse of discretion in denying petitioners motion to

discharge attachment by counter-bond in the amount of P12,600,000.00.

Says the trial court in its Order of June 13, 1994:

"xxx (T)he counter-bond posted by [petitioner] Insular Savings Bank should

include the unsecured portion of [respondents] claim of P12,600,000.00 as

agreed by means of arbitration between [respondent] and [petitioner]; Actual

damages at 25% percent per annum of unsecured amount of claim from

October 21, 1991 in the amount of P7,827,500.00; Legal interest of 12% percent

per annum from October 21, 1991 in the amount of P3,805,200.00; Exemplary

damages in the amount ofP2,000,000.00; and attorneys fees and expenses of

litigation in the amount of P1,000,000.00 with a total amount ofP27,237,700.00

(Adlawan vs. Tomol, 184 SCRA 31 (1990)".

Petitioner, on the other hand, argues that the starting point in computing the

amount of counter-bond is the amount of the respondents demand or claim

only, in this case P25,200,000.00, excluding contingent expenses and

unliquidated amount of damages. And since there was a mutual agreement

between the parties to temporarily, but equally, divide between themselves the

said amount pending and subject to the final outcome of the arbitration, the

amount of P12,600,000.00 should, so petitioner argues, be the basis for

computing the amount of the counter-bond.

The Court rules for the petitioner.

The then pertinent provision of Rule 57 (Preliminary Attachment) of the Rules

of Court under which the appellate court issued its assailed decision and

resolution, provides as follows:

"SEC. 12. Discharge of attachment upon giving counter-bond. At any time

after an order of attachment has been granted, the party whose property has

been attached, . . . may upon reasonable notice to the applicant, apply to the

judge who granted the order or to the judge of the court which the action is

pending, for an order discharging the attachment wholly or in part on the

security given. The judge shall, after hearing, order the discharge of the

attachment if a cash deposit is made, or a counter-bond executed to the

attaching creditor is filed, on behalf of the adverse party, with the clerk or

judge of the court where the application is made in an amount equal to the

value of the property attached as determined by the judge, to secure the

payment of any judgment that the attaching creditor may recover in the