Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ADR Chapter 1

Uploaded by

iwanttoeat0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views12 pagesADR cases

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentADR cases

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

33 views12 pagesADR Chapter 1

Uploaded by

iwanttoeatADR cases

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. L-3567. August 20, 1907. ]

KAY B. CHANG, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. ROYAL

EXCHANGE ASSURANCE CORPORATION OF LONDON,

Defendant-Appellant.

Del-Pan, Ortigas & Fisher, for Appellant.

John W. Sleeper, for Appellees.

SYLLABUS

1. FIRE INSURANCE; CONDITION PRECEDENT. policy of

fire insurance contained a clause providing that in the event of a

loss under the policy, unless the company should deny all

liability, as a condition precedent to the bringing of any suit by

the insured upon the policy the latter should first submit the

question of liability and indemnity to arbitration. Such a condition

is a valid one in law, and unless it be first complied with no

action can be brought.

2. ID.; ID.; WAIVER. If in the course of the settlement of a

loss. however, the action of the company or its agents amounts

to a refusal to pay, the company will be deemed to have waived

the condition precedent with reference to arbitration and a suit

upon the policy will lie.

D E C I S I O N

WILLARD, J . :

The arbitration clause in the fire policy in question in this case is

in part as follows:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"If a disagreement should at any time arise between the

corporation and the assured . . . respect of any loss or damage

alleged to have been caused by fire, every such disagreement,

when it may occur (unless the corporation shall deny liability by

reason of fraud or breach of any of the conditions, or because

the claimant has by some other means waived his rights under

the policy), shall be referred to the arbitration of some person to

be selected by agreement of both parties . . . And by virtue of

these presents it is hereby expressly declared to be a condition

of this policy, and an essential element of the contract between

the corporation and the insured that unless the corporation shall

demand exemption from liability by reason of fraud, breach of

conditions, or waiver, as stated, the assured, or claimant, shall

have no right to commence suit or other proceedings before any

court whatever upon this policy until the amount of the loss or

damage shall have been referred, investigated, and determined

as above provided, and then only for the amount awarded, and

the obtaining of such an award shall be a condition precedent to

the institution of any suit upon this policy and to the liability and

obligation of the corporation to pay or satisfy any claim or

demand based upon this policy."cralaw virtua1aw library

The conditions contained in this clause of the policy are valid,

and no action can be maintained by the assured unless as

award has been made or sought, or unless the company has

denied liability on some of the grounds stated therein. (Hamilton

v. Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company, 136 U.S.,

242.) The duty of asking a submission to arbitration does not

rest exclusively upon the company. If it takes no action in that

respect it is the duty of the assured to do so, and to ask that

arbitrators be appointed for the purpose of determining the

amount of the loss, in accordance with the provisions of this

policy. The company may, however, by its conduct, waive the

provisions of this clause relating to arbitration. In fact, this is

expressly stated in the policy itself, as will be seen from the

quotation above made, and the principal question in this case is

whether there has been such waiver or not.

Simple silence of the company is not sufficient. If it remains

passive, it is the duty of the assured to take affirmative action to

secure arbitration. Neither will the failure of the company to

return proofs of loss, or its failure to point out defects therein,

amount to a waiver of the arbitration clause. These acts may

amount to a waiver of the clause requiring the furnishing of

proofs of loss, but such an action can not constitute proof that

the company has refused to pay the policy because the

defendant has failed to comply with the terms and conditions

thereof.

It is claimed, however, by the plaintiffs and appellees, that

affirmative action was taken by the company indicating its

purpose not to pay anything to the insured.

The property insured, consisting of a stock of goods, was

entirely destroyed by a fire on the 11th day of March, 1905. On

the same day the plaintiffs notified the agent of the defendant of

the loss and within fifteen days thereafter presented to the

company a detailed statement of the articles which had been

destroyed and of their value. Plaintiffs were notified by the

company that this proof was insufficient and that they must

obtain the sworn certificates of two merchants to the truth of

their statement. This was done within a few days. Plaintiffs were

again notified that their proof was insufficient. Various interviews

were had between the agent of the defendant and the plaintiff

Chang and the plaintiffs lawyer between the latter part of March

and the 21st of June, 1905. During this time the plaintiffs

furnished additional evidence relating to the justice of their claim

and were told that their proofs were still insufficient. No

indication was made by the companys agent as to what other

proofs should be furnished, he offering, however, at one of the

interview to settle the claim for 3,000 pesos. This offer was

refused by the plaintiffs. In the final interview on June 21,

between the companys agent and the counsel for the plaintiffs,

the former said:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"I can not go on with your case, Mr. Sleeper; I have not enough

proof.

"Q. What did Mr. Sleeper state?

"A. I think, so far as I can remember, that he said he wanted to

bring the matter to a basis, but I would not say so to the

court."cralaw virtua1aw library

This action was commenced on the 24th of June, 1905. The

plaintiffs at no time requested the appointment of arbitrators.

After the suit had been commenced, and on the same day, the

defendant requested in writing that arbitrators be appointed in

accordance with the terms of the policy. This was the first

communication in writing which the defendant made to the

plaintiffs after the loss.

Under all the circumstances in the case, we think that the

statement made by the companys agent on the 21st day of

June amounted to a denial of liability on the ground that proper

proofs of loss had not been presented and that, therefore, there

had been a failure of the assured to comply with one of the

terms of the policy. The delay of the company in taking any

affirmative action between the 11th day of March and the 21st

day of June; its repeated statements that the proofs were

insufficient without indicating in any way what other proofs

should be furnished, and its final statement that it could go no

further with the case, was sufficient evidence to show that it did

not intend to pay. This view is somewhat confirmed by what

took place afterwards before the arbitrators, both of whom were

appointed by the defendant in accordance with the terms of the

policy. At the first meeting of these arbitrators the defendant

objected to any award being made upon the ground that the

proof of loss which had been furnished was sworn to before a

notary public and not before the municipal judge, as required by

the provisions of the Code of Commerce.

In the case of The Phenix Insurance Company v. Stocks (149

Ill., 319) the company wrote two letters to the insured, in the first

of which they said:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"The circumstances under which this fire occurred are such that

we do not feel justified in extending to you any measure of

grace, in considering your claim, which you may not fairly

demand under the terms of the policy. There is at least one fact

that looks very peculiar, and until our minds are relieved of the

doubts which we have come to receive in regard to the integrity

of this loss, we shall offer you no benefits that you may not

demand under a strict construction of the policy."cralaw

virtua1aw library

In the other letter the company said:jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"Replying to your letter of August 23d, received this morning, we

beg to say that our views of this matter have been fully

expressed in our previous correspondence, and have nothing at

this time to add."cralaw virtua1aw library

The court said (p. 334):jgc:chanrobles.com.ph

"The mere silence of the company would not amount to a waiver

of its right to insist upon the condition [as to arbitration], but

when it placed its determination upon the grounds stated in the

correspondence, which were such as could not be submitted to

arbitration under the provisions of the policy, it must be held to

have waived the condition requiring arbitration (German Ins. Co.

v. Gueck, 130 Ill., 345), and especially is this so where the

assured would be misled to their prejudice into bringing suit

upon the policy without first having obtained an award. The

company was not bound to speak at all., but when asked in

effect, what its determination was, if it answered, good faith

required that it should disclose the true ground of its

defense."cralaw virtua1aw library

It is apparent in the case at bar that the counsel for the plaintiffs

sought the interview of June 21 for the express purpose of

finding out what the decision of the company was, and after

receiving the answer which has been heretofore quoted, the

plaintiffs were fully justified in bringing the action at once,

without seeking any arbitration.

Judgment was entered in the court below in favor of the

plaintiffs for the sum of 5,265 pesos and 25 centavos, with

interest from the 24th of June, 1905, and costs. It is claimed by

the appellant that the finding of the court below as to the amount

of the loss is not justified by the evidence. A great many

witnesses were presented by each side, but the only persons

who had any real knowledge as to the amount of stock in the

store at the time of the fire, and as to its value, were the plaintiff

Chang and his clerk. They testified that it was worth more than

10,000 pesos, the amount named in the policy. No one of the

witnesses for the defendant fixed the value of the stock then on

hand at more than 500 pesos. The arbitrators appointed by the

defendant found that the value was 2,106 pesos. The

defendants agent testified that during negotiations he offered to

settle for 3,000 pesos. That the plaintiff (Chang) was carrying on

a business of some importance was proved at the trial by the

introduction of the records of the customs in Cebu, by which it

appeared that between the month of July, 1904, and February,

1905, he had imported through the custom-house goods which

with the duty added were of the value of 4,758 dollars and 48

cents, money of the United States, and the plaintiff, Chang,

testified that he had no hand at the time of the fire a large

amount of property, products of the country, which were not

imported through the customs.

In view of all the evidence in the case, we can not say that it

preponderates against the finding of the judge below as to the

amount of the loss.

The judgment of the court below is hereby affirmed, with the

costs of this instance against the Appellant.

Torres, Johnson, and Tracey, JJ., concur.

G.R. No. L-21549 October 22, 1924

TEODORO VEGA, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

THE SAN CARLOS MILLING CO., LTD., defendant-appellant.

Fisher, Dewitt, Perkins, & Brady, John R. McFie, Jr., Jesus

Trinidad, and Powell & Hill for appellant.

R. Nolan and Feria & La O for appellee.

ROMUALDEZ, J .:

This action is for the recovery of 32,959 kilos of centrifugal

sugar, or its value, P6,252, plus the payment of P500 damages

and the costs.

The defendants filed an answer, and set up two special

defenses, the first of which is at the same time a counterclaim.

The Court of First Instance of Occidental Negros that tried the

case, rendered judgment, the dispositive part of which is as

follows:

By virtue of these considerations, the court is

of opinion that with respect to the complaint,

the plaintiff must be held to have a better right

to the possession of the 32,959 kilos of

centrifugal sugar manufactured in the

defendants' central and the latter is sentenced

to deliver them to the plaintiff, and in default,

the selling price thereof, amounting to

P5,981.06 deposited in the office of the clerk

of the court. Plaintiff's claim for damages is

denied, because it has not been shown that

the defendant caused the plaintiff any

damages. Plaintiff is absolved from

defendant's counterclaim and declared not

bound to pay the such claimed therein.

Plaintiff is also absolved from the

counterclaim of P1,000, for damages, it not

having been proved that any damages were

caused and suffered by defendant, since the

writ of attachment issued in this case was

legal and proper. Without pronouncement as

to costs.

So ordered.

The defendant company appealed from this judgment, and

alleges that the lower court erred in having held itself with

jurisdiction to take cognizance of and render judgment in the

cause; in holding that the defendant was bound to supply cars

gratuitously to the plaintiff for the cane; in not ordering the

plaintiff to pay to the defendant the sum of P2,866 for the cars

used by him, with illegal interest on said sum from the filing of

the counterclaim, and the costs, and that said judgment is

contrary to the weight of the evidence and the law.

The first assignment of error is based on clause 23 of the Mill's

covenants and clause 14 of the Planter's Covenant as they

appear in Exhibit A, which is the same instrument as Exhibit 1.

Said clauses are as follows:

23. That it (the Mill Party of the first part)

will submit and all differences that may arise

between the Mill and the Planters to the

decision of arbitrators, two of whom shall be

chosen by the Mill and two by the Planters,

who in case of inability to agree shall select a

fifth arbitrator, and to respect and abide by the

decision of said arbitrators, or any three of

them, as the case may be.

x x x x x x x x x

14. That they (the Planters--Parties of the

second part) will submit any and all

differences that may arise between the parties

of the first part and the parties of the second

part of the decision of arbitrators, two of

whom shall be chosen by the said parties of

the first part and two by the said party of the

second part, who in case of inability to agree,

shall select a fifth arbitrator, and will respect

and abide by the decision of said arbitrators,

or any three of them, as the case may be.

It is an admitted fact that the differences which arose between

the parties, and which are the subject of the present litigation

have not been submitted to the arbitration provided for in the

above quoted clauses.

Defendant contends that as such stipulations on arbitration are

valid, they constitute a condition precedent, to which the plaintiff

should have resorted before applying to the courts, as he

prematurely did.

The defendant is right in contending that such covenants on

arbitration are valid, but they are not for the reason a bar to

judicial action, in view of the way they are expressed:

An agreement to submit to arbitration, not

consummated by an award, is no bar to suit at

law or in equity concerning the subject matter

submitted. And the rule applies both in

respect of agreements to submit existing

differences and agreements to submit

differences which may arise in the future. (5

C. J., 42.)

And in view of the terms in which the said covenants on

arbitration are expressed, it cannot be held that in agreeing on

this point, the parties proposed to establish the arbitration as a

condition precedent to judicial action, because these clauses

quoted do not create such a condition either expressly or by

necessary inference.

Submission as Condition Precedent to Suit.

Clauses in insurance and other contracts

providing for arbitration in case of

disagreement are very similar, and the

question whether submission to arbitration is

a condition precedent to a suit upon the

contract depends upon the language

employed in each particular stipulation.

Where by the same agreement which creates

the liability, the ascertainment of certain facts

by arbitrators is expressly made a condition

precedent to a right of action thereon, suit

cannot be brought until the award is made.

But the courts generally will not construe an

arbitration clause as ousting them of their

jurisdiction unless such construction is

inevitable, and consequently when the

arbitration clause is not made a condition

precedent by express words or necessary

implication, it will be construed as merely

collateral to the liability clause, and so no bar

to an action in the courts without an award. (2

R. C. L., 362, 363.)

Neither does not reciprocal covenant No. 7 of said contract

Exhibit A expressly or impliedly establish the arbitration as a

condition precedent. Said reciprocal covenant No. 7 reads:

7. Subject to the provisions as to arbitration,

hereinbefore appearing, it is mutually agreed

that the courts of the City of Iloilo shall have

jurisdiction of any and all judicial proceedings

that may arise out of the contractual relations

herein between the party of the first and the

part is of the second part.

The expression "subject to the provisions as to arbitration,

hereinbefore appearing" does not declare such to be a condition

precedent. This phrase does not read "subject to the

arbitration," but "subject to the provisions as to arbitration

hereinbefore appearing." And, which are these "provisions as to

arbitration hereinbefore appearing?" Undoubtedly clauses 23

and 14 quoted above, which do not make arbitration a condition

precedent.

We find no merit in the first assignment of error.

The second raises the most important question in this

controversy, to wit: Whether or not the defendant was obliged to

supply the plaintiff which cars gratuitously for cane.

The Central, of course, bound itself according to the contract

exhibit A in clause 3 of the "Covenant by Mill," as follows:

3. That it will construct and thereafter maintain

and operate during the term of this agreement

a steam or motor railway, or both, for

plantation use in transporting sugar cane,

sugar and fertilizer, as near the center of the

can ands as to contour of the lands will permit

paying due attention to grades and curves;

that it will also construct branch lines at such

points as may be necessary where the

present plantations are of such shape that the

main line cannot run approximately through

the center of said plantations, free of charge

to the Planters, and will properly equip said

railway with locomotives or motors and cars,

and will further construct a branch line from

the main railway line, mill and warehouses to

the before mentioned wharf and will further

construct yard accomodations near the sugar

mill. All steam locomotives shall be provided

which effective spark arresters. The railway

shall be constructed upon suitable and

properly located right-of-way, through all

plantations so as to give, as far as

practicable, to each plantations equal benefit

thereof; said right-of-way to b two and one-

half meters in width on either said from the

center of track on both main line and switches

and branches.

By this covenant, the defendant, the defendant bound itself to

construct branch lines of the railway at such points on the estate

as might be necessary, but said clause No. 3 can hardly be

construed to bind the defendant to gratuitously supply the

plaintiff with cars to transport cane from his fields to the branch

lines agreed upon on its estate.

But on March 18, 1916, the defendant company, through its

manager Mr. F. J. Bell, addressed the following communication

to the plaintiff:

DEAR SIR: In reply to yours of

March 15th.

Yesterday I tried to come out to San

Antonio to see you but the railway

was full of cars of San Jose and I

could not get by with my car. I will try

again as soon as I finish shipping

sugar. The steamer is expected

today.

I had a switch built in the big cut on

San Antonio for loading your cane

near the boundary of Santa Cruz. will

not this sufficient? We have no

another switch here and I hope you

can get along with the 3 you now

have.

Some of the planters are now using

short switches made of 16-lb.

portable track. These can be placed

on the main line at any place and

cars run off into the field and loaded.

I think one on your hacienda would

repay you in one season.

The rain record can wait.

Sincerely yours,

SAN CARLOS MILLING CO.,

LTD. (Sgd.) F.J. BELL

"Manager"

It is suggested to the plaintiff in this letter that he install a 16-lb.

rail portable track switch, to be used in connection with the main

line, so the cars may run on it. It is not suggested that he

purchase cars, and the letter implies that the cars mentioned

therein belong to the defendant.

As a result of this suggestion, the plaintiff bought a portable

track which cost him about P10,000, and after the track was

laid, the defendant began to use it without comment or objection

from the latter, nor payment of any indemnity for over four

years.

With this letter Exhibit D, and its conduct in regard to the same,

the defendant deliberately and intentionally induced the plaintiff

to believe that by the latter purchasing the said portable track,

the defendant would allow the free use of its cars upon said

track, thus inducing the plaintiff to act in reliance on such belief,

that is, to purchase such portable track, as in fact he did and

laid it and used it without payment, the cars belonging to the

defendant.

This is an estoppel, and defendant cannot be permitted to

gainsay its own acts and agreement.

The defendant cannot now demand payment of the plaintiff for

such use of the cars. And this is so, not because the fact of

having supplied them was an act of pure liberality, to which

having once started it, the defendant was forever bound, which

would be unreasonable, but because the act of providing such

cars was, under the circumstances of the case, of compliance of

an obligation to which defendant is bound on account of having

induced the plaintiff to believe, and to act and incur expenses on

the strenght of this belief.

The question of whether or not the plaintiff was under the

necessity of first showing a cooperative spirit and conduct, does

not affect the right which he thus acquired of using the cars in

question gratuitously.

We do not find sufficient reason to support the second

assignment of error.

The point raised in the third assignment of error is a

consequence of the second. If the plaintiff was entitled, as we

have said, to use the cars gratuitously, the defendant has no

right to demand any payment from him for the use of said cars.

The other assignments of error are consequences of the

preceding ones.

We find nothing in the record to serve as a legal and sufficient

bar to plaintiff's action against the defendant for the delivery of

the sugar in question, or its value. A discussion as to the

retention of this deposit to apply upon what is due by reason

thereof made in the judgment appealed from, is here necessary.

The parties do not raise this question in the present instance.

Furthermore, it has not been proven that the plaintiff owes the

defendant anything by reason of such deposit.

The judgment appealed from is hereby affirmed with the costs of

this instance against the appellant. So ordered.

Johnson, Street and Villamor, JJ., concur.

G.R. Nos. L-26216 and 26217 March 5, 1927

MONICO PUENTEBELLA, ET AL., plaintiffs-appellants,

vs.

NEGROS COAL CO., LTD., ET AL., defendants-appellants.

H. V. Bamberger and Simeon Bitanga for plaintiffs-appellants.

Eliseo Hervas for defendants-appellants.

OSTRAND, J .:

These are appeals by both parties from the following decision of

the Court of First Instance of Occidental Negros:

Due to the close connection between these

two cases, they were tried jointly by

agreement of the parties. They are actions for

there recovery of damages for the sum of

P50,000 and P40,000, respectively.

It is alleged that the plaintiffs, having bound

themselves to plant sugar cane which the

defendants, in turn, promised to mill in a

sugar central which they were to erect,

complied with their contract, but the latter did

not erect the central in due time, this delay

causing the former to lose all of the said crop.

It is further prayed that the contracts executed

for that purpose be cancelled.

It is alleged in the answer of the defendants

that the Negros Coal Co., Ltd., was dissolved

on June 16, 1923, by an order of the Court of

First Instance of Iloilo, but that its rights,

actions and obligations were placed in charge

of the commercial firm of Hijos de I. de la

Rama & Co., of which the defendant Esteban

de la Rama is the manager; that due to force

majeure, fortuitous events, and other

circumstances independent of the will of the

defendants, they were unable to complete the

construction of the sugar central within due

time and that the plaintiffs, after the

construction of the central, refused to mill their

cane and did nothing to lessen their losses.

In the first case, they presented a

counterclaim for P18,000 in damages for

violation of the milling contract, and a cross-

complaint for the foreclosure of the mortgage

credits against Juliana Puentebella Vda. De

Ferrer, for the sum of P39,114.63 and a

penalty of P5,867.19; against Pedro Ferrer,

for the sum of P19,557.30, and against

Francisco Ferrer for the sum of P19,557.30,

plus P2,933.59 for attorney's fees and

expenses of litigation. In the second case,

they likewise presented a counterclaim of

P1,800 as damages for violation of the milling

contract, and a cross-complaint for the

foreclosure of the mortgage credit for the sum

of P44,169.90, plus a penalty of P6,625.48.

And, moreover, in the first case it is alleged as

a special defense, that it having been agreed

in the contract upon which the plaintiffs base

their action, that before commencing any

litigation they would submit their differences to

arbitrators, the plaintiffs have done nothing to

comply with this stipulation. Indeed,

paragraph 17 of the contract, Exhibit A, reads

as follows:

"That they shall submit each and every one of

the differences that may arise between the

party of the first part and the party of the

second part to the decision of arbitrators, two

of whom shall be selected by the party of the

first part and two by the party of the second

part, who, in case of a disagreement, shall

select a fifth arbitrator, and they shall respect

and abide by the decision of said arbitrators

or any three of them, as the case may be."

As may be seen, this clause states absolutely,

and not as a mere condition precedent to

judicial action, that all differences between the

contracting parties shall be submitted to

arbitrators, who decision the parties shall

respect and abide by, and the clause is,

therefore, void. (Rudolph Wahl & Co. vs.

Donaldson, Sims & Co., 2 Phil., 301, and

Teodoro Vega vs. San Carlos Milling Co.,

Ltd., G.R. No. 21549, promulgated October

23, 1924.) This is on one hand, while on the

other are the documents, Exhibits 19, 20 and

21 executed separately by the plaintiffs on the

same date as Exhibit A, all representing

mortgage loans, and with the exception of

Exhibit 20, they further more contain a

stipulation on the part of Hijos de I. dela

Rama to finance the farm laborers of the

plaintiffs and to mill the cane in the sugar

central of the Negros Coal Co., Ltd., but

contain no agreement to submit the

differences that might arise between the

parties to arbitrators. These documents

constitute a transaction of binding force,

because they define the duty and obligation of

each party, which is not the case in Exhibit A,

in which an option is left to the plaintiffs to

miss or not to mill their sugar cane in said

central because, as may be inferred from its

context, the purpose was only to obtain, as

the Negros Coal Co., Ltd., did obtain, the right

of way on the plaintiffs' land.

At the trial of these cases the parties

submitted a stipulation of facts, paragraph 5

of which, literally, reads as follows:

"That the partnership denominated "Hijos de I.

de la Rama" was organized in the 1907 for a

period of ten years; that said period having

expired in 1917, Esteban de la Rama was

appointed liquidator of the property of the

partnership by agreement between the

members; that after the liquidation had

commenced, and before the year 1920,

Esteban de la Rama bought all the rights of

his copartners in the property of the said firm

in liquidation, to be paid in installments, with

the right to use the firm name, but with the

obligation no to dispose of the property of the

firm in liquidation while the price stipulated in

the contract of sale of rights remained

unpaid;" Esteban de la Rama being,

therefore, according to this agreement, the

sole owner of the firm of Hijos de I. de la

Rama, and having taken over the rights,

actions and obligations of the Negros Coal

Co., Ltd., as alleged in the first paragraph of

the answer, it appears that he is at present in

possession of all the rights, actions and

obligations which originated from contractual

relations entered into both cases by the

plaintiffs on the one side and the, then,

corporation, known as the Negros Coal Co.,

Ltd., and the Hijos de I. de la Rama on the

other, by virtue of the documents, Exhibits A,

B, 19, 20 and 21.

On March 7, 1924, after the plaintiffs had filed

their complaint in case No. 2911, the plaintiff

Pedro Ferrer died, and intestate proceedings

having been instituted, the court, upon

motion, and under date of August 23, 1924,

ordered the substitution, in this case, of the

deceased Pedro Ferrer by Francisco Ferrer,

judicial administrator of his estate.

Exhibit A is a contract executed in Iloilo by

Esteban de la Rama, in his capacity as

President of the Negros Coal Co., Ltd., on the

one hand, and by Juliana Puentebella, Pedro

Ferrer and Francisco Ferrer on the other,

which contract contains, among other things,

a stipulation that the party of the first part shall

erect a sugar central in the sitio denominated

Labilabi, Escalante, Occidental Negros, with a

railway across the land of the party of the

second part for the transportation of sugar

cane to the central, the said party of the

second part binding itself to mill the sugar

cane in said central, receiving 45 per cent of

the total amount of the sugar manufactured;

and the party of the second part grants an

easement of way on their land to the party of

the first part and, at its option, 'to mill or not to

mill' its cane in the said sugar central.

Exhibits 19, 20 and 21, as has already been

stated, are contracts of mortgage loan

executed separately, the first by Juliana

Puentebella, the second by Pedro Ferrer and

the third by Francisco Ferrer, as debtors, and

by the Hijos de I. dela Rama, as creditor in

each of said contract, it being further

stipulated in the first and the third contract

that the loans were to be used exclusively in

the production of sugar cane on the

mortgaged land; that the mortgagors bound

themselves to mill their sugar cane every year

in course of construction, the central to

receive 45 per cent of the total sugar

manufactured from said cane, and that the

amounts borrowed should be amortized by an

annual payments during ten agricultural

harvests; and while, as has been said, Exhibit

20 is simply a mortgage loan by reason of its

date, notwithstanding that it is the same as

that of Exhibits A, 19 and 21, or July 23, 1920,

from the date of the notarial acknowledgment

in connection with Exhibit A, executed jointly

by the plaintiffs in case No. 2911, it can be

inferred that this loan, as the others, was

made by the commercial firm of Hijos de I. de

la Rama for the purpose of financing the

haciendas of the plaintiffs for the cultivation of

sugar cane and to supply the sugar central of

the Negros Coal Co., Ltd.

Exhibit B executed on June 17, 1920, by and

between Monico and Luis Puentebella on the

one hand and Hijos de I. de la Rama on the

other, is practically the same as Exhibits 19,

and 21, and provides for a mortgage loan for

agricultural purposes and milling in said

central, but with the following additional

clause:

In case the proposed sugar central of the

Negros Coal Co., Ltd., is not in position the

first year to mill the sugar cane of the

mortgagor in time, the mortgagee binds itself

to furnish the mortgagor with the sum of from

P20,000 to P pesos, Philippine currency,

for the erection, under the supervision of the

mortgagors, of a 12-horse-power mill for

grinding muscovado sugar, and to install and

equip the same with all the necessary

material for the operation and milling of

muscovado sugar; in that case of their sugar

cane planted in Jonobjonob, Escalante,

Occidental Negros, and the said mortagagees

will receive one-third of the sugar

manufactured by the mortgagors in

consideration of all of the foregoing.

By virtue of said contracts A, B, 19, 20 and

21, all of the plaintiffs in both cases tilled the

mortgaged land and planted sugar cane

during the months of September, October,

November and December of 1920 and

January of 1921 and, at about the time the

cane was ripe Monico Puentebella at various

times advised De la Rama, by letter, that his

cane was ripening and he, therefore,

demanded the erection of a mill for

muscovado sugar in accordance with the

agreement in the clause quoted from Exhibit

B, which brought forth the following reply:

PROGRESO 28, ILOILO, March 29, 1921

MR. MONICO PUENTEBELLA

Bacolod, Occidental Negros

MY DEAR SIR: Replying to your letter of the 25th inst. which I

have just received, I wish to state the following: That the

Escalante Central will be erected; in fact, it is also wish to state

that about two weeks ago all of the plans of said central were

forwarded to Mr. Fortunato Fuentes, and that long ago all of the

bricks, both common and fireproofs, as well as the cement and

lime were sent there. Therefore, there is no need for you to

worry about your sugar cane planted in Cervantes, for I have

more interest than you in milling it in order to recover the

P30,000 which I have advanced to you for said purpose.

Very respectfully,

E. DE LA RAMA

Mrs. Juliana Puentebella, in company with her son Francisco

Ferrer, also made a trip to Iloilo in March, 1922, for a

conference with Esteban de la Rama and to advise him that

their cane, as well as the cane of her sons Pedro and Francisco

was ripe and some of it over-ripe, and asked permission to mill it

in the San Carlos sugar Central, Occidental Negros, in view of

the fact that neither the sugar central of the Negros Coal Co.,

Ltd., nor the railway had been constructed, but Mr. De la Rama

laid down certain conditions which the petitioner considered

burdensome; so nothing was done about milling the cane in the

San Carlos Central.

Esteban de la Rama while testifying concerning the petition of

Mr. Monico Puentebella for the construction of a muscovado

sugar mill , said:

For various reasons. Because when Mr. Monico Puentebella

required me to comply with this clause of the contract, he did so

at a time when I was building the central and I figured that the

machinery would be installed in my mill, as work had already

been begun and Mr. Fuentes was looking for the machinery and

was to install it before Mr. Puentebella's cane had ripened and

the P20,000 would not be needed. In the second place, before

that date, when Mr. Puentebella demanded the P20,000 of me, I

had received a letter from the Bank of the Philippine Islands.

From the contents of the letter received from the Bank of the

Philippine Islands, I was of the opinion that said Bank was the

owner of the land and held Torrens title thereto, and that it did

not understand why Mr. Puentebella was cultivating this land

which belonged to it without its permission, and that it did not

understand why Mr. Puentebella to make a contract with it; and

as Mr. Puentebello refused to do so, I thought it useless for us

to meddle with a property which was not ours.

It having been positively stated in Exhibit B that the mortgagors

Monico and Luis Puentebella are the undivided coowners with

the Hijos de I. de le Rama and the Bank of the Philippine

Islands of the mortgaged property, the last statement of Esteban

de la Rama, in his testimony aboved quoted, that he considered

it useless to build the mill on the said land, appears to be merely

an excuse for not voluntarily complying with his obligation, and

his estimate as to the completion of the central which he was

building having been made by himself alone, and without the

concurrence of the other contracting party, is not a sufficient

reason for excusing him, for the fulfillment of a contract cannot

be left to the will of one of the contracting parties.

The result was that on account of the said reasoning of Mr. de la

Rama with respect to the Puentebellas and his demands upon

the Ferrers, the cane belonging to both of them was left in the

fields without being milled, and with the exception of a small

quantity belonging to the Puentebellas which they had sent to

the San Carlos Central for milling was drying out and

deteriorating and became a complete loss.

It is alleged, nevertheless, that the delay in the construction of

the central was due to force majeure, fortuitous events and

other circumstances independent of the will of the defendants,

in support of which they attempted to prove that there had been

a strike in the factory of George Fletcher & Co., Ltd., Derby,

England, from whom they had ordered their machinery, which

strike delayed matters, but the evidence in this particular

respect consists of reports from the agent of the defunct firm of

the Cooper Company, with offices in the Philippine Islands,

through which company the said machinery was contracted for,

and, naturally, as it comes from an interested party and is,

moreover, hearsay, it is of little or no value. And even if it be

considered competent evidence, the total loss of the plaintiffs'

crop cannot be attributed to force majeure, fortuitous events or

other circumstances, for it was provided in the construction of

the central, a mill would be furnished for the manufacture of

muscovado sugar which would not only mill the cane of the

Puentebellas, but also that of the defendant Esteban de la

Rama, and the same would have been done with the cane of

the Ferrers, because their lands adjoin.

It is also claimed that the frequent rains, inundations and

crumbling of the earth considerably interrupted the construction

of the earth considerably interrupted the construction of the

central, and, judging from Exhibits 6-A to 6-X, which are all

letters from the person in charge of its construction, and which

include the period from November 5, 1920 to January 22, 1922,

approximately one year and four months, it rained almost

incessantly, which appears to have been an unusual occurrence

of which the Weather Bureau should have had knowledge, and

whose opinion would have been more impartial.

Conceding, however, a certain value to this contention, it would,

nevertheless, seem that these circumstances should have

caused Mr. De la Rama to take all the necessary precautions for

the purpose of insuring the milling of the plaintiffs' crop,

especially so as it appears from the following letter that he

himself foresaw losses:

February 18, 1921

THE COOPER COMPANY

Iloilo, Iloilo , P. I.

MY DEAR SIRS: In view of the long delay in the manufacture of

the equipment which we have contracted for our central at

Escalante, a delay which is almost double the time specified in

the contract and which is causing us a great loss in not being

able to mill at present, we have decided to cancel the order for

said equipment, and you will do us the favor of returning the

P50,000 which we advanced at the time of signing the contract,

together with the interest thereon.

Yours sincerely,

HIJOS DE I. DE LA RAMA

BY E. DE LA RAMA

It is likewise alleged that after the central had been constructed

the plaintiffs refused to mill their cane there and did nothing to

minimized their losses, but the delay in constructing the said

central having been expressly admitted in their previous

defense, the conclusion is that it was completed after the

season was over and the cane was over-ripe, for which reason,

although the defendants were notified that the central would

begin to operate within the first fifteen days of September, 1922,

they cease to cut their cane, because it was already useless

and dried out as stated in the following letters of the plaintiffs:

BACOLOD, September 2, 1922.

Messrs. HIJOS DE I. DE LA RAMA

P. O. Box 298

Iloilo, Iloilo

MY DEAR SIRS: In answer to your letter of the 26th of last

month, I have to inform you that my cane is completely dried out

and useless for milling purposes. You are not ignorant of cause

of this unfortunate result of my efforts in planting cane on the

Cervantes Estate, for I have not even been able to produce

muscovado sugar from it on account of your failure to comply

with that part of our contract which binds you to make us a

further loan of P20,000 in order to obtain machinery for that

purpose in case of delay in the completion of your central, as, in

fact, was the case. This advice from you has come extremely

late and at a time when it is impossible to remedy the situation,

as it is impossible to revive dead cane. You know very well that

these disastrous consequences of my affairs are due to no fault

of mine, but are due to your failure in not complying with your

part.

Very respectfully,

ESCALANTE,

OCCIDENTAL NEGROS,

November 2, 1925

MR. FORTUNATO FUENTES

Manager of the H. I. R. Central

Labilabi, Escalante, Occidental Negros.

MY DEAR SIR: In answer to your favor of September 28th last, I

must advise you that the fields planted with sugar cane,

according to the terms of our contract to mill it in the H. I. R.

Central, are completely dead on account of not having been

milled in said central at the proper time, for which reason it has

been impossible to plant again, the non-fulfillment of said

contract having caused unconsiderable damage.

Very respectfully,

FRANCISCO FERRER

Administrator of J. Vda. de

Ferrer and Pedro Ferrer

It is said in these exhibits that the cane was useless, dried out

and dead, which fact is proven by Exhibits D, E and F,

communications to Monico Puentebella from the San Carlos

Central to which Central, as already stated, Mr. Puentebella

sent a few tons of cane for milling, which letters, dated from

April 2 to 9, 1922, imply that they sent the cane there not later

than the month of March, and, as may be seen from the letters,

the milling was a failure and a complete loss, because said cane

was already over-ripe and because it was sent from Escalante

to the municipality of San Carlos for shipment, which is the only

means of transportation, even today, between the said towns,

and very costly; and considering that the cane which was sent

to idea may be formed of the condition of the plaintiffs' sugar-

cane fields in said month of April, and so disastrous was this

shipment that, according to the testimony of Luis Puentebella,

the share of the agriculturist was not even sufficient to cover the

expenses.

On the other hand, Francisco Ferrer, after the conference of him

and his mother with Esteban de la Rama, attempted to mill his

cane in the sugar mill on the neighbor boring estate belonging to

Rosario Sanz, but the latter refused to do so because the

season was over.

If therefore, the plaintiffs' cane was over-ripe in March, 1922 it

seems certain that when they were notified on September 28,

1922 (Exhibit P addressed to the Ferrers) and on August 26,

1922 (Exhibit 16 addressed to Monico to mill next September),

or when the central commenced to produce sugar on

September 15, 1922, in accordance with the stipulation of facts,

the cane at the end of this period and useless for milling, and

moreover if in March, according to the result of the milling at the

San Carlos, it did not given an average yield and was milled at a

loss, we are more than justified in saying that five and a half

months afterwards the yield would have been almost nothing.

The witnesses for the defendants testified, however, that cane

on virgin land used for the cultivation of sugar cane, lasts about

eighteen months and Mr. De la Rama stretched it to 24 months,

which implies that the plaintiffs cane was still in condition to be

milled when the central commenced to operate in September,

1922, because according to the evidence, the plaintiffs' cane

was planted in September, October, November and December,

1920; and in January, 1921; but applying this same theory to the

plaintiffs first plantings, in April, 1922, they twenty months old, or

more than eighteen, for which reason, were sent to San Carlos

in March they could no longer yield an average production, as

stated by the Central, and, naturally, the best evidence as to

whether the cane is still use full is not the theory of how long it

will last, but the result of the milling.

In "Cane Sugar," by Noel Deerr, page 29, it is said:

The harvest season generally extends over a period of four to

six months and exceptionally in the arid localities may be

continued over the whole year with such stops only as are

required for overhaul and repairs. At the beginning of the crop

an unripe cane of lower sugar content is harvested; the

percentage of sugar gradually increases and is usually at a

maximum in the third and fourth months of harvest, after which it

increases as the cane becomes over-ripe. Taking Cuba as an

example, in December the cane will contain from 10 per cent toll

per cent of sugar, the maximum of 14-15 per cent being

obtained in March and April, after which a fall occurs, which is

very rapid if the crop is prolonged after the seasonal mid-year

rains fall. It is easy to see that the combined questions of factory

capacity, capital lost, duration of harvest, and yield per cent on

cane form a most important economic problem, which is usually

further complicated by a deficiency in the labour supply.

Early observations, later confirmed by chemists upon the

establishment of sugar centrals in this province, coincide with

Mr. Deerr's theory, because, after the cane is ripe, what is called

a "reversion" takes place in the juice or the saccharose is

converted into glucose, which takes place very rapidly, the cane

becoming more fibrous each time, until it finally dries up and

dies.

The plaintiffs Ferrer claim to have lost 120 lacsas of sugar cane,

and the plaintiffs Puentebella, allege a loss of 115 lacsas (a

lacsa a unit of 10,000 sugar-cane plants) which they both

testified having planted in their respective fields. In regard to the

former's plants in the affidavit of Antonio M. Lizares, then an

employee of Esteban de la Rama, defendants' Exhibit 4, it is

said that the witness inspected the Canquinto Estate of

Francisco Ferrer and found about 60 lacsas of stalks which,

according to his calculation, should produce from 25 to 30 piculs

of sugar each, which corroborates the testimony of Francisco

Ferrer that he planted 70 lacsas on the Canquinto Estate, and

does to contradict the testimony of this same witness that his

mother, Juliana Puentebella, planted thirty lacsas on the

Mamposod land, while his brother planted twenty lacsas on the

Ampanan land, making a total of 120 lacsas, which lands in

Canquinto, Mamposod and Ampanan, according to the

testimony of Francisco Ferrer himself, are respectively, those

mortgaged by them to the Hijos de I. de la Rama by virtue of the

documents, Exhibits 19, 20 and 21 and that, according to the

stipulations made in Exhibits 19, and 21 and the interpretation

that has been given to Exhibit 20, the mortgagors bound

themselves to plant sugar cane. This testimony of Francisco

Ferrer is also corroborated by Rosario Sanz, who testified

having seen 100 lacsas of sugar cane on Ferrer's land in March,

1922, which were over-ripe, but if milled in said month would,

nevertheless, have produced 40 piculs of sugar per lacsa, and

would have produced 50 piculs had they been milled at the

proper time. In regard to the cane of the plaintiffs Puentebella, it

appears that in March, 1922, they asked the witness Simeon S.

de Paula to inspect their fields. He testified not less than 100

lacsas and which might have produced 50 when it was ripe, but

they were then going out of season. In exhibit 5, the affidavit of

Gerardo Alunan, Uldarico Suison and Antonio Lizares, them

employees of Mr. De la Rama, it is stated that they went to a

place called Baldosa where they received the information that

there was a field of 17,000 plants, and that they were informed

at the Cervantes Estate that 48 lacsas of sugar-cane plants had

been brought from Cadiz and had been planted in five fields,

and that more than 7,000 plants were brought from Jonobjonob,

making, therefore, a total of fifty lacsas and four thousand sugar

cane plants. But, it may be seen, that all that is stated in this

affidavit in regard to the quantity of plants is mere hearsay and

is not a act personally observed by the informants. It does not

controvert the estimate of Simeon S. de Paula, nor of Dionisio

Patrata who accompanied the former on the inspection of the

fields of the plaintiffs Puentebella, in March, 1922, who likewise

estimated that there were 100 lacsas of cane on the Cervantes

Estate, which should have produced 5,000 piculs of sugar had

the cane been milled in due time; nor does it contradict the

testimony if Jose Alemani to the effect that at a place higher up

adjoining his land, the plaintiffs then had three fields planted

with thirteen or fourteen lacsas. It is true that Esteban de la

Rama testified that the Puentebella fields visited by him

contained only about seven lacsas, but it appears that this

assertion is of little value, as it may be inferred that his visit did

not extend to all of the planted fields; besides, his estimate does

not come anywhere near that contained in the affidavit of his

representatives, Exhibit 5.

Antonio M. Lizares, in his affidavit, Exhibit 4, estimates an

average of thirty piculs of sugar per lacsa from Ferrer's cane,

but made no estimate in his affidavit Exhibit 5, in regard to

Puentebella's cane. But from this estimate , as compared with

that of German Carballo, Simeon S. de Paula, Rosario Sanz,

and Dionisio Patrata, all sugar growers, some with considerable

experience in the cultivation of sugar cane, who also inspected

the plaintiffs' cane , and who unanimously stated that a lacsa of

cane produces 50 piculs of sugar, none of them having a any

interest in these cases nor any proven motives for favoring or

opposing any of the parties, it seems that the preponderance of

judgment is in favor of the latter. Consequently, the 120 lacsas

of sugar-cane stalks belonging to the plaintiffs Ferrer should

have produced 6,000 piculs of sugar, from which 45 per cent

must be deducted which, in accordance with the contracts,

belongs to the central, leaving a balance of 3,300 piculs. The

115 lacsas of the plaintiffs Puentebella should have produced

5,750 piculs of sugar, of which 45 per cent belongs to the

central, leaving a balance of 3,162.50 piculs. The parties having

agreed in the stipulation of facts that the price of the 1921-22

crop was P10.50 a picul of centrifugal sugar, the plaintiffs Ferrer

should have obtained, as a product, P34,650 and the

Puentebellas P33,206.25. From these amounts must be

deducted the expenses of raising the crop and putting the sugar

on the market in Iloilo, at the rate of P1.50 per picul, or P9,000

and P8,625, respectively, leaving a net balance, therefore, of

P25,650 for the former and P24,631.25 for the latter.

The plaintiffs allege, furthermore, that on account of not having

harvested their crops, they could not prepare their fields for the

cultivation of the ratoon crop for the agricultural year of 1922-23,

an having lost the crop for that year, they pray for damages for

such loss. The defendants likewise set up a counterclaim for

damages for the loss of the central's share of the plaintiffs's crop

for the agricultural year of 1922-1923 by reason of the plaintiffs'

failure to prepare their fields. The plaintiffs, not having prepared

their fields for the ratoon crops or to cultivate the same, the

ratoons requiring as much cultivation as new planting, nor

performed any work, nor invested any capital, it is obvious that

they are not entitled to any indemnity for claim any share in a

supposed crop of 1922-23, nor recover by the defendants' own

acts in violating their contracts with the plaintiffs.

In support of the defendants' counterclaim in regard to the

plaintiffs Ferrer, there were presented, Exhibit 19, which is a

mortgage to secure a loan for the sum of P25,000, with interest

at 12 per cent per annum, payable annually, during ten

agricultural years, executed by the plaintiff Juliana Puentebella

Vda. de Ferrer, in favor or that the debtor shall pay 15 per cent

of such amounts as may be claimed, in case of litigation, for

attorney's fees and expenses; Exhibit 20, which is a mortgage to

secure per annum, payable within ten years, executed by the

deceased Pedro Ferrer in favor of the Hijos de I. de la Rama;

and Exhibit 21, which is also a mortgage for the sum of

P12,500, with interest at 12 percent per annum, likewise

payable annually during ten agricultural years, and which

mortgage was executed by Francisco Ferrer in favor of the Hijos

de I. de la Rama it having been furthermore stipulated therein

that, in case of litigation, the debtor should pay 15 per cent of

such amounts as may be claimed, for attorney's fees and the

expenses of litigation; and in regard to the plaintiffs Puentebella,

Exhibit B was introduced which is a mortgage for the sum of

P30,000 with interest at 12 per cent per annum, payable

annually during twenty agricultural years, it having been further

stipulated that in case of litigation, the debtor shall pay 15 per

cent of such amounts as may claimed, for attorney's fees and

expenses; and Exhibit 18, which is a statement of the partial

receipts and payments made by the plaintiffs, to wit:

1920 Nature of transaction Debit Credit Balance

June 18, Received on account ......................... 5,000.00 ............ 5,000

July 2, Received on account ......................... 5,000.00 ............ 10,000

July 31, Double plough .................................... 323.00 ............ 10,323

Aug. 8, 1 tractor ................................................. 3,978.00 ............ 14,301

Aug. 23, Received on account ......................... 5,000.00 ............ 19,301

Sept. 13, Received on account ......................... 2,500.00 ............ 21,801

Sept. 22, Received on account ......................... 1,400.00 ............ 23,201

Oct. 4, Received on account ......................... 900.00 ............ 24,101

Oct. 18, Received on account ......................... 2,000.00 ............ 26,101

Nov. 17, Received on account ......................... 2,000.00 ............ 28,101

Nov. 17, Received on account ......................... ............ 500.00 28,601

Received on account ......................... ............ 500.00 28,101

Received on account ......................... 323.00 ............ 27,778

Dec. 8, Received on account ......................... 2,222.00 ............ 30,000

1921

Received on account ......................... 1,590.00 ............ 31,590

It will be observed that the installments in these contracts are

not due, but as the plaintiffs themselves, in their respective

complaints, ask for the cancellation of the contracts, it is clear

that they have tacitly renounce the terms agreed upon. It is not

believed, however, that the counterclaimants are entitled to any

amount for attorney's fees and expenses of litigation as

stipulated in the contracts Exhibits B, 19 and 21, because these

two cases having been brought by the plaintiffs for violation of

said contracts by the defendants, it would not be equitable and

just their non-fulfillment of the contracts being the determining

cause of the actionto award them any amount for attorney's

fees and expenses to defend these actions, which would not

have arisen had the defendants been loyal to their contracted

obligations.

The mortgage loans earn interest at the rate of 12 per cent per

annum, while the most that the defendants can be ordered to

pay the plaintiffs on the amounts claimed by them is legal

interest from the filing of the complaints herein, a circumstance

which would place Mr. De la Rama in an advantageous position

if the amounts claimed by the parties time the damages were

caused. Such set-off is believed to be equitable because, as a

matter of fact, were it not for the defendants' nonfulfillment of

their obligations, said plaintiffs have lost their respective crops,

or contracted the lost through the fault, delinquency, or violation

of the contracts by their creditors themselves, which are legal

causes, against the guilty party.

In view of the foregoing, the following judgment is rendered.

In regard to the complaint in case No. 2911,

(1) The defendant Esteban de la Rama is

ordered to pay the plaintiffs the sum of

P25,650, and the costs of this action;

(2) In regard to the cross-complaint the

plaintiffs are ordered to pay Esteban de la

Rama, to wit: Juliana Vda. de Ferrer, the sum

of P25,000, with interest at 12 per cent per

annum from August 3, 1920, the date of the

receipt of this amount (Exhibit 22); Pedro

Ferrer, the sum of P12,500 with interest at 12

per cent per annum from August 3, 1920

(Exhibit 23), and Francisco Ferrer, the sum of

P12,500, with interest at 12 per cent per

annum from August 3, 1920 (Exhibit 24);

(3) The counterclaim for damages is

dismissed and it is ordered that the amounts

awarded to the plaintiffs and the principal of

the mortgage loan, which they are hereby

ordered to pay, compensate each other

proportionately up to the concurrent amount,

said compensation to be effective as of April

1, 1922; and

(4) It is ordered that the balance from the

compensation be deposited with the court by

the plaintiffs within three months from the date

hereof, with the admonition that failing to do

so the sale of the mortgaged property will be

ordered and the proceeds thereof applied to

the amount of this judgment with respect to

the counterclaim.

In regard to the complaint in case No. 2912,

(1) The defendant Esteban de la Rama is

ordered to pay the plaintiffs the sum of

P24,581.25 and the costs of this action;

(2) In regard to the cross-complaint, the

plaintiffs are ordered to pay Esteban de la

Rama the sum of P31,590, with interest at 12

percent per annum from the various dates of

the partial receipts, as shown by Exhibit 18,

quoted herein;

(3) The counterclaim for damages is

dismissed and it is ordered that the amounts

awarded to the plaintiffs and the ordered to

pay, compensate each other proportionately

up to the concurrent amount, said

compensation to be effective as of April 1,

1922.

The plaintiffs under their first three assignments of error

maintain that they are entitled to damages for the loss of the

ratoon crop for the year 1923, but we agree with the court below

that such damages are too remote. It is further to be noted that

plaintiffs made no effort to reduce the loss for 1923 by

cultivating the ratoons or by again planting the land to cane or

other crops after the failure of the 1922 cane crop and it is

elementary that a party injured by a breach of contract cannot

recover damages for any loss which he might have avoided with

ordinary care and reasonable expense. (Warren vs. Stoddard,

105 U. S., 224.) Assuming for the sake of the argument that the

damages claimed were not too remote, there is no evidence

sufficiently showing what the amount of the recoverable

damages would have been if the plaintiffs had done their duty

and sought to minimize the losses.

The plaintiff-appellants' fourth assignment of error is evidently

the result of carelessness in reading the appealed judgment and

need not be discussed.

The defendant-appellants present the following assignments of

error:

I. The court below committed an error in

rendering judgment in case G.R. No. 26217

against Esteban de la Rama, ignoring the

Negros Coal Co.

II. The court below committed an error in

holding that the defendants were obliged, by

the terms of the contracts Exhibits A and B, to

grind the plaintiffs' sugar cane in 1921.

III. Even supposing that the defendants were

obliged to grind the plaintiffs' cane in the

central of the Negros Coal Company, the

court below committed an error in holding the

defendants liable for damages for not having

completed the central in 1921.

IV. The court below committed an error in not

dismissing the complaint of Messrs. Ferrer

(G.R. No. 26217), the plaintiffs not having

complied with the condition precedent to

submit their difference to arbitrators before

filing their complaint.

V. Even supposing that the defendants were

liable for damages, the court below committed

an error in ordering Esteban de la Rama to

pay Messrs. Ferrer the sum of P25,650, and

to Messrs. Puentebella the sum of

P24,581.25, by way of damages.

The questions raised by the assignments quoted are fully

discussed in the decision of the court below and hardly require

further elucidation. As to the first assignment, we may say,

however, that aside from the fact that the Negros Coal Co., Ltd.

has been dissolved and that De la Rama figures as its

successor in interest and liabilities, it is further to be noted that

the losses suffered by the plaintiffs were due to De la Rama's

misleading representations and to his failure to fulfill his

promises. In these circumstance, it was not error to give

judgment for damages against him and not against the Negros

Coal Co., Ltd.

The fourth assignment of error is likewise without merit. The

arbitration clause in paragraph 17 of the Ferrer contract, Exhibit

A, expressly provides that the parties shall "abide by the

decision of said arbitrators or any three of them, as he case may

be." The clause does not merely to the courts; it provides for a

final determination of legal rights by arbitration. In other words,

an attempt was make to take the disputes between the parties

out of the jurisdiction of the courts. An agreement to that effect

is contrary to public policy and is not binding upon the parties.

The defendant-appellants' other assignments of error relate only

to questions of fact in regard to which the findings of the court

below are fully sustained by the evidence. The judgment

appealed from is affirmed without costs to any of the parties. So

ordered.

Johnson, Street, Malcolm, Villamor, Ostrand, Romualdez and

Villa-Real, JJ., concur.

You might also like

- Xavier 6csDocument11 pagesXavier 6csiwanttoeatNo ratings yet

- Schedule of StayDocument1 pageSchedule of StayiwanttoeatNo ratings yet

- Labor Law and Social Legislation - 2013 Bar Exam SyllabiDocument8 pagesLabor Law and Social Legislation - 2013 Bar Exam Syllabielvie_arugayNo ratings yet

- Sections 2 To 9 Corporation CodeDocument19 pagesSections 2 To 9 Corporation CodeiwanttoeatNo ratings yet

- UST Legal Aid Intern Rating 2015Document1 pageUST Legal Aid Intern Rating 2015iwanttoeatNo ratings yet

- Cases Under Sec. 15Document2 pagesCases Under Sec. 15iwanttoeatNo ratings yet

- Spouses Bacolor Vs Banco FilipinoDocument1 pageSpouses Bacolor Vs Banco FilipinoiwanttoeatNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Atuhaire Pia - Coffee Project Proposal 1Document57 pagesAtuhaire Pia - Coffee Project Proposal 1InfiniteKnowledge91% (32)

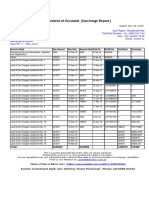

- Surcharge Report BTKSC-P05164Document1 pageSurcharge Report BTKSC-P05164Nasir Badshah AfridiNo ratings yet

- Scholtz 2016 AIChE - Journal PDFDocument12 pagesScholtz 2016 AIChE - Journal PDFYaqoob AliNo ratings yet

- Delta System LimitedDocument81 pagesDelta System LimitedMahbub E AL MunimNo ratings yet

- TVM 2021Document58 pagesTVM 2021mahendra pratap singhNo ratings yet

- Tender Document Warehouse (Financial)Document518 pagesTender Document Warehouse (Financial)Aswad TonTong100% (3)

- Tri Level 2 Promo 17Document5 pagesTri Level 2 Promo 17asdfafNo ratings yet

- Management of Habib Bank LTD PakistanDocument30 pagesManagement of Habib Bank LTD PakistanMohammad Ismail Fakhar HussainNo ratings yet

- Presented By:-1.bijayananda Sahoo 2.jibesh Kumar Mohapatra 3.naresh Kumar Sahoo 4.soumya Surajit BiswalDocument37 pagesPresented By:-1.bijayananda Sahoo 2.jibesh Kumar Mohapatra 3.naresh Kumar Sahoo 4.soumya Surajit BiswaljibeshmNo ratings yet

- FilipinoSariSariStore Draft HMalapitDocument25 pagesFilipinoSariSariStore Draft HMalapitRomy Wacas100% (2)

- Government Accounting Chapter 2Document5 pagesGovernment Accounting Chapter 2Jeca RomeroNo ratings yet

- MELCs GeneralMathematics G11 v1Document12 pagesMELCs GeneralMathematics G11 v1Marc Muriel RuadoNo ratings yet

- Advt No 37 2019Document1 pageAdvt No 37 2019Zulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- StockFarmer DD PackDocument6 pagesStockFarmer DD PackAnonymous fe4knaZWjmNo ratings yet

- TAX Calalang v. LorenzoDocument3 pagesTAX Calalang v. LorenzoAnathea CadagatNo ratings yet

- Surviving A Global CrisisDocument98 pagesSurviving A Global CrisisCristiano Savonarola100% (1)

- 616099155-Far-Fetch 2Document1 page616099155-Far-Fetch 2Bajs MajaNo ratings yet

- Nature of South Korean Economic GrowthDocument59 pagesNature of South Korean Economic GrowthwisdomseunNo ratings yet

- Top Glove Corporation BHD Corporate PresentationDocument21 pagesTop Glove Corporation BHD Corporate Presentationalant_2280% (5)

- Trust Preferred CDOs A Primer 11-11-04 (Merrill Lynch)Document40 pagesTrust Preferred CDOs A Primer 11-11-04 (Merrill Lynch)scottrathbun100% (1)

- Jeda ConsDocument2 pagesJeda ConsNathan ChinhondoNo ratings yet

- TRAIN With ComputationDocument21 pagesTRAIN With ComputationJohny BravyNo ratings yet

- DOW Theory LettersDocument2 pagesDOW Theory Lettersrosalin100% (3)

- Singapore Post LTD: Fair Value: S$0.93Document27 pagesSingapore Post LTD: Fair Value: S$0.93MrKlausnerNo ratings yet

- Audit of Cash and Marketable SecuritiesDocument21 pagesAudit of Cash and Marketable Securitiesዝምታ ተሻለNo ratings yet

- Proposal Final Year ProjectDocument61 pagesProposal Final Year ProjectHazmi ZainuldinNo ratings yet

- "Bank Lending, A Significant Effort To Financing Sme'': Eliona Gremi PHD CandidateDocument6 pages"Bank Lending, A Significant Effort To Financing Sme'': Eliona Gremi PHD CandidateAnduela MemaNo ratings yet

- Leave and License AgreeDocument4 pagesLeave and License AgreeYogesh SaindaneNo ratings yet

- A Seminar Report On: "Safety of e Cash Payment"Document19 pagesA Seminar Report On: "Safety of e Cash Payment"Abhinav GuptaNo ratings yet

- US Internal Revenue Service: p1582Document27 pagesUS Internal Revenue Service: p1582IRS100% (9)