Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yikuan Lee

Uploaded by

Dobre Diana0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views19 pagesThis study investigates the relationship between communication strategy and new product performance. It models product innovativeness as a moderator that influences the relationship. The authors emphasize that the impact of innovativeness to producers is different from that to consumers.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis study investigates the relationship between communication strategy and new product performance. It models product innovativeness as a moderator that influences the relationship. The authors emphasize that the impact of innovativeness to producers is different from that to consumers.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views19 pagesYikuan Lee

Uploaded by

Dobre DianaThis study investigates the relationship between communication strategy and new product performance. It models product innovativeness as a moderator that influences the relationship. The authors emphasize that the impact of innovativeness to producers is different from that to consumers.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

The Impact of Communication Strategy on Launching New

Products: The Moderating Role of Product Innovativeness

Yikuan Lee and Gina Colarelli OConnor

Academic literature is lled with debate on whether product innovativeness

positively impacts new product performance (NPP) because of increasing competi-

tive advantage or negatively impacts performance due to consumers fears of novel

technology and resultant resistance to adopt. This study investigates this issue by

modeling product innovativeness as a moderator that inuences the relationship

between communication strategy and new product performance. The authors

emphasize that the impact of innovativeness to producers is different from that to

consumers and that the differences have strategic impact when commercializing

highly innovative products. Product innovativeness is conceptualized as multi-

dimensional, and each dimension is tested separately. Four dimensions of

innovativeness are exploredproduct newness to the rm, market newness to the

rm, product superiority to the customer, and adoption difculty for the customer.

In this study, communication strategy is comprised of preannouncement strategy

and advertising strategy. First, the relationship between whether or not a pre-

announcement is offered and NPP is explored. Then three types of preannounce-

ment messages (customer education, anticipation creation, and market preemp-

tion) are investigated. Advertising strategy is characterized by whether the

advertisement campaign at the time of launch was based primarily on emotional or

functional appeals.

Using empirical results from 284 surveys of product managers, the authors nd

that the relationship between communication strategy and NPP is moderated by

innovativeness, and that the relationships differ not only by degree but also by type

of innovativeness. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Introduction

S

ince the late 1980s, the issue of identifying

factors that account for new product success

and failure has drawn substantial attention.

Among those many factors, product innovativeness is

one of the most important. There are two streams of

literature that examine the relationship between a

products innovativeness and its market performance:

the new product performance literature (NPP) [19,26,

42,57,70], and the launch strategy literature [8,30,

38,79]. The evidence, however, is not conclusive. Some

of the work argues that product innovativeness

positively impacts new product performance (NPP)

because it increases a rms competitive advantage

[11,26], which in turn creates additional incentives for

rms to invest in innovations and increase product

innovativeness as they attempt to compete in high-

tech markets.

Other studies indicate that innovativeness nega-

tively impacts performance because of customers

fears associated with adopting unproven technology.

Address correspondence to Yikuan Lee, Department of Marketing

and Supply Chain Management, The Eli Broad Graduate School of

Business (NBC), Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824.

Phone: 517 353-6381; E-mail: leeyik@msu.edu.

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:421

r 2003 Product Development & Management Association

These studies emphasize the negative effects that

increased product innovativeness may have on the

uncertainty that consumers experience (i.e., high

switching costs, high risk, and increased investment

of time to learn new behaviors) with highly innovative

products [49]. Technological fear is an essential issue

for commercialization of high-tech products [34].

Some consumers deal with the fear of uncertainty

and new learning requirements of the new innovative

products simply by avoiding or hesitating in pur-

chases of the new and improved version [21].

Finally, Cooper and Brentani (1991) propose that

the relationship between product innovativeness

and commercial success is U-shaped [18]. According

to this view, products exhibiting either high or

low degrees of innovativeness are likely to be more

successful than those in-between. The authors explain

that highly innovative products should create more

opportunities for differentiation and competitive

advantage and hence impact positively on perfor-

mance. Conversely, less innovative products are more

familiar, less uncertain, may have higher synergy, and

thus are likely to enjoy a higher success rate.

Closing the Gap

We believe there are at least two reasons for these

inconclusive results. First, we believe that product

innovativeness as a construct is not dened clearly

and unambiguously. What is perceived as offering a

clearly superior set of features by the producer in fact

may be perceived as a highly risky alternative to the

consumer, who must deal with higher levels of

technical uncertainty than comfortable with. Directly

relating innovativeness to performance without

clearly identifying different dimensions (both the

bright side and the dark side) of innovativeness can

cause invalid interpretation of the results.

A second reason for the inconclusive results that

surround the role of innovativeness, we believe, is that

it has been treated typically as an independent

variable that directly impacts NPP. It may be that

innovativeness is modeled more appropriately as a

moderator between launch strategy variables and

performance. Innovativeness itself does not guarantee

success. A successful innovation must be novel and, at

the same time, easy to comprehend [26]. Without an

appropriate introduction strategy, a products inno-

vativeness may be perceived by customers as offering

uncertainty and risk rather than as providing superior

benets. This negative perception of innovativeness

may lead to adoption resistance. For example, Philips

introduced its digital compact cassette (DCC) tech-

nology and attempted to replace existing recordable

tape technology (cassette tapes). The company has

been unable to persuade consumers to switch from

existing analog cassette tapes to its DCC system.

Philips failure might in part be attributed to its poor

product launch advertising strategy, which failed to

emphasize the issue of backward compatibility and

did nothing to dispel consumers confusion over the

benets of digital recording technology [35]. Com-

munication with customers to manage their percep-

tions of product innovativeness is critically important,

especially when launching a highly innovative pro-

duct that customers may reject due to lack of product

knowledge.

It is conceivable that the mechanisms used to

successfully prepare the market for a new product

introduction would be highly different depending on

the characteristics of the product. Therefore, in this

article, we do not look at innovativeness as an

independent variable that directly impacts new

product success but rather as a variable that

moderates the relationship between communication

strategies and NPP. Modeling innovativeness as a

moderator, we believe, has more managerial meaning

because the conceptual framework illustrates how to

communicate with customers under different condi-

tions of innovativeness.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

Dr. Yikuan Lee is visiting assistant professor in the marketing &

supply chain department at Michigan State University. Her

research interests include commercializing innovative products,

high-tech marketing, network effects, new product development,

and knowledge management in strategic alliances. She received the

Best Dissertation Award and the Best Paper Award at the 1999

Product Development and Management Association (PDMA)

International Conference. She also won the Edl and Edith Darger

Dissertation Prize in Management in recognition of outstanding

academic achievement and promise for a successful career in 2000.

Dr. Gina OConnor is assistant professor in the Lally School of

Management and Technology at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

(RPI). Her elds of interest include new product development and

radical innovation. Before joining RPI in February 1988, Dr.

OConnor earned her Ph.D. in marketing and corporate strategy at

New York University. Prior to that time, she spent several years

with McDonnell Douglas and Monsanto Chemical. The majority of

her research efforts focus on how rms link advanced technology

development to market opportunities. She has authored many

academic articles on the topic and is coauthor of the book Radical

Innovation: How Mature Companies Can Outsmart Upstarts,

published by Harvard Business School Press (2000).

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

5

Objectives of the Article

In the literature, product innovativeness is typically

measured based on its impact on the producer [25].

The focus of most of this work investigates the impact

of technological newness on the new product devel-

opment process [32,40,44,45,70,71,78]. These studies,

however, focus on the part of the new product

development process that occurs prior to launch. In

this study, we are interested in the role of innovative-

ness in commercializing a new product rather than on

the internal product development process. A new

product may be unique and superior to competitive

offerings due to a nely tuned stage-gate product

development process but may still fail due to a poor

launch [15]. The type of launch strategy employed is

one of the key determinants of new product success.

Although many academic scholars have focused on

identifying the most successful launch strategies

[3,8,38,73,79], we believe that the relationship among

launch strategy, product innovativeness, and NPP is

not understood fully yet. This research question

requires that we consider innovativeness along

dimensions that are perceived by and impact both

producers and consumers when introducing a product

to the marketplace.

There are two goals of this study. The rst is to

model the communication mix factors that would

inuence consumers perceptions of product innova-

tiveness and to relate those to NPP. A rms

communication strategy is a critical element of its

launch planthe element most directly responsible

for aiding the markets acceptance of a new product.

We then model the products innovation character-

istics as moderators of this relationship. We select two

commonly accepted elements of a communication

strategypreannouncement strategy and advertising

strategyand investigate how to communicate with

customers under various conditions of innovative-

ness.

There are several reasons for choosing these

two particular communication strategies. First, a lack

of product knowledge causes a need for customers to

be educated before the innovative product is intro-

duced to the market. Preannouncement not only

can preempt the market against competitors but

also can be used as a tool to familiarize potential

customers with the new product concept and can help

shape their expectations. Second, advertising strategy

plays an essential role throughout the purchasing

decision process. Empirical results from previous

studies indicate that the magnitude of advertising

expenditures (or advertising effort) signicantly im-

pacts NPP [20,70]. Beyond the level of expenditures,

the content of the advertising message is critical to

help ease customer anxiety about new technologies.

A second goal of this study is to clarify several

dimensions of innovativeness. While many studies

have addressed the role of a products innovativeness

as a substantial differentiating factor in managing in

new product development and launch, there has not

yet been a clear, systematic articulation of this

concept [22]. Recent conceptual work offers a

thoughtful taxonomy of types of innovativeness [25].

However, there is as yet little empirical testing of

separate measures of these concepts and their

differential effects in managerial contexts. By clarify-

ing multiple perspectives on this issue and by

measuring them separately, we highlight the impor-

tance of treating the denition of innovativeness

carefully and completely for strategic and managerial

decision-making purposes.

This article is organized as follows. The rst

section discusses the differences in the meaning of

innovativeness to producers and to consumers. Four

dimensions of innovativeness are identied. The

second section presents the conceptual model that

illustrates the impact of two types of communication

strategies on product performance, each moderated

by various dimensions of innovativeness. Several

hypotheses are developed, and the relationships

between those hypotheses and previous literature also

are discussed. The next section describes the metho-

dology, including the sample, data collection proce-

dures, and measure development. The last section

presents the empirical results and the managerial

implications. We close with conclusions and some

thoughts about the limitations of this study.

Multiple Dimensions of Innovativeness

Several empirical studies have investigated successful

launch strategies under varying levels of innovative-

ness [8,38,79]. The denitions of innovativeness,

however, are not standard, making interpretation of

research results somewhat difcult [23,25]. First, the

concept has been operationalized at different levels of

analyses: the industry, the rm, and the product level.

Second, it has been measured from a variety of

perspectives, including the rm as developer, the rm

as an adopter, and consumers as adopters. These

6 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

various combinations have led to at least the

following sets of measures of innovativeness: the

extent to which a product impacts an industrys

competitive structure [74]; the extent to which a

product impacts the relative advantage of a rm

among its rivals [1]; the extent to which developing an

innovation causes the rm to move into arenas of

technological and market uncertainty [8]; the extent

to which the product offers new to the world benets

[10]; and the extent to which an innovation impacts

established customer behavior patterns, consumption

requirements, and expectations [49,58,77].

The literature on launch strategy measures innova-

tiveness primarily based on product newness to the

rm and affords much less attention to the impact of

product newness on consumption behaviors. The impact

of innovativeness on consumption behaviors depends

on how customers perceive the new product. Surpris-

ingly, few authors measure innovativeness by con-

sidering the potential impact on consumers

purchasing and consumption behavior when discuss-

ing the relationship between innovativeness and

launch strategies. Mick and Fourniers work (1998)

is an exception in that they have begun to identify the

issues conceptually [49]. Sethi et al. (2001) measured

new product innovativeness based on whether the

novelty of the product is appropriate from the

perspective of the marketplace [67]. To date, however,

no specic empirical data on the impact of this

phenomenon on product performance has been

reported. Following from this, none of the launch

strategy studies focus on the nature of the commu-

nication messages for effective management of

customers perceptions of product innovativeness.

We suggest that in order to investigate the relation-

ship between innovativeness and product introduc-

tion, the following two questions must be considered:

(1) What is the impact of innovativeness on produ-

cers? and (2) How might innovativeness impact on

consumption behaviors via consumer perceptions?

The meaning of innovativeness to producers may be

very different from that to the consumers, and

therefore impacts differently on the relationship

between launch strategy and NPP. The differences

have strategic meaning when launching a new

product.

The impact of innovativeness on producers. The

impact of innovativeness on producers is apparent

during both the development process and the

products launch. If the new product relies on

technology never previously used in the industry,

then product innovativeness will inuence develop-

ment activities such as idea development and screen-

ing, technical development, and strategic planning.

Conventional wisdom suggests that highly innovative

products should benet more than less innovative

products from procient execution of technical

development activities [69]. Some studies suggest that

the interaction between research and development

(R&D) and marketing should be emphasized espe-

cially when innovativeness is high [32,71]. Iansiti

(1995) proposes that technology integration is critical

to the introduction of new technologies because it

provides a mechanism for the accumulation of system

level knowledge of product and process and for its

convergence into the integration of technologies for

the next generation [40].

However, if the products novelty lies primarily in

the extent to which it causes new markets to develop

but the technical uncertainty is relatively low, then the

impact of innovativeness on the producer is more

intense during the commercialization stage than in the

development stage. If the product is a really new

producta radical innovation that creates a line of

business that is new not only for the rm but also for

the marketplacethen the level of innovativeness

also will impact on the types of activities required to

learn about new markets [21,53]. New communication

strategies, new distribution channels, and new custo-

mer development approaches may be needed in order

to introduce the new product to unfamiliar markets,

and entirely new skills sets may be required to create

new market spaces.

The impact of innovativeness on consumers. The

meaning of innovativeness to consumers is very

different from that to producers [49,77]. A product

that requires technology that is new to the rm

necessarily may not be unfamiliar to the marketplace;

indeed the rm simply may be expanding its own

competency base into competitive territory. The

resultant product may not be very innovative as far

as the market is concerned. For example, the radical

innovation of substituting the vacuum tube with the

transistor is a technological breakthrough for the

radio market, but it requires little from consumers in

terms of usage pattern changes or new learning. Yet

another example is the recent set of technological

breakthroughs in new materials to speed the proces-

sing capabilities of computer chips (from silicon to

gallium arsenide to silicon germanium). From the

consumers perspective, this innovation has little

impact on their adoption and use patterns; these are

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

7

just subsequent generations of PCs that operate at a

higher speed. By comparison, the invention and

commercialization of the Internet has impacted

substantially consumers behavior and thus is per-

ceived as a radical innovation by consumers, although

the technology has existed and has been used for

several decades.

The impact of innovativeness on consumers

depends more on the degree of learning and adoption

efforts required of them rather than on the newness of

the technology itself [65]. A marketing innovation

necessarily does not need to be technically novel,

so long as customers perceive its offering as novel

[11]. If an innovation is perceived as very difcult

to adopt rather than as a unique product with

substantial new benets, the marketers challenge

is to work hard in communicating with customers

to translate the technical uncertainty into useful

benets. Appropriate communication strategies at

launch can reduce effectively the negative impact of

technical fears on the adoption of an innovative

product.

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

Figure 1 presents our conceptual framework. Two

communication tools, preannouncement strategy and

advertising strategy, directly impact on NPP. How-

ever, the relationship between communication strat-

egy, and NPP is moderated by four dimensions of

innovativeness: product newness to the rm; market

newness to the rm; product superiority to the

customer; and adoption difculty for the customer.

Preannouncement strategy is dened as a formal,

deliberate communication before a rm actually

introduces the new product into the market [24,63].

In this study, we posit that preannouncement has a

stronger positive impact on performance for highly

innovative products than for less innovative products

based on the following reasons. First, the benets of

preannouncing are tied to the advantages of being a

pioneer in the market. Empirical evidence suggests

many advantages of being rst to the market

[30,63,64,76,79]. Primary among those is that pre-

announcing helps the rm develop an initial level of

opinion leader support and favorable word of mouth

needed to accelerate the diffusion of the innovative

product [76].

Second, as a communication tool, preannounce-

ment strategy can reduce consumers risk perception

of an innovative product. From the consumers

perspective, high innovativeness may be related to

fear of unfamiliar product/technology functions,

substantial change of consumption patterns, and

concomitantly high switching costs [24,62]. Switching

costs may be a signicant impediment to consumer

adoption of a highly innovative product and may

favor current competitors by acting as a barrier to

new entrant [58]. Under conditions of high customer

switching costs, preannouncement may begin the

process of educating potential customers about how

New Product Performance

Market penetration rate

Market share

Profitability

Customer satisfaction

Market extension

Product newness to the firm

Market newness to the firm

Product superiority to the customer

Adoption difficulty to the customer

Competitive Intensity

Market Turbulence

Technology Turbulence

Preannouncement Strategy

Advertising Strategy

Product Innovativeness

Communication strategy

Market Environment

Figure 1: The Impact of Communication Strategy on Performance Moderated by Product Innovativeness

8 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

to change over with minimum disruption and costs

[24].

Although there may be risks of preannouncement

(i.e., revealing intentions to competitors), these

conditions are less likely to be the case with highly

innovative products. The reason is that if the rm has

strong patent protection or owns its own distribution

system, it may be able to signal with less regard for

competitive cuing [33]. Therefore, we expect that

engaging in preannouncement activities will lead to

higher performance for highly innovative products

(that may be perceived as high risk and high switching

costs by the customers) than for less innovative

products.

H1: Preannouncing the new product will have a

stronger positive impact on NPP when innovativeness

is high than when it is low.

Advertising message strategy is a term used in this

study to convey the nature of the advertising appeal.

According to Petty and Cacioppos elaboration like-

lihood model (ELM), persuasion may take a central

and/or peripheral route [55]. In the central route, a

person engages in extensive cognitive elaboration (i.e.,

issue-relevant thinking) of the message. However, a

person may take the peripheral route if he or she is

not motivated or lacks the ability to process the issue-

relevant information. In the case of the peripheral

route, post-communication attitudes are based on

message cues that are irrelevant to forming a reasoned

opinion (e.g., ones liking of the endorser).

Building on the ELM, we identify two types of

advertising strategies based on the content of the

messages in the ad. Functional ads use rational

appeals to demonstrate a products attributes and

features in an objective manner and thus correspond

to the central route persuasion process. Emotional ads

(such as humor, slice-of-life, fear, or guilt appeals)

express the subjective and symbolic benets of the

product, thus incorporating the peripheral route.

Message appeals that are emotional, evaluative,

transformational, or feeling messages often are

contrasted with more rational, informational, factual,

or thinking appeals [36,47]. We believe that con-

sumers are more likely to process functional appeals

via the central route, while they are more likely to

process emotional appeals via a peripheral route.

Identifying these two types of advertising strategies

is important and strategic in the context of commu-

nicating with customers about highly innovative

products. In some cases, consumers may not have

the product knowledge to process the functional

appeals (e.g., information about technical details or

sophisticated product features). Under those condi-

tions emotional ads that evoke consumers positive

feelings about the product through peripheral routes

may be a more effective approach.

Traditionally, educating the market has been

emphasized heavily for introducing innovative pro-

ducts. Beard and Easingwood (1996) propose that

market education is a tactic that takes the most

generic approach to attacking the market and is most

appropriate when the market is unaware of the

existence of the technology [8]. With this tactic,

marketing resources are concentrated mostly on

educating potential customers about the novel tech-

nology and its possibilities [16]. The newer and more

innovative a product is, the more likely it is that

the public might not appreciate it at the beginn-

ing [66], and in this case, customers need to be taught

to recognize the differential benets of the novel

product [72].

However, are customers with little product knowl-

edge able to evaluate such technically oriented

information as is given in a functional ad? Studies

demonstrate that rational communications are more

effective for well-educated or analytical people than

for less educated or less analytical people [12,37].

Information about physical features may be mean-

ingless to consumers with little product knowledge.

Previous studies have proposed that the efciency of

functional appeals depends on the degree of con-

sumers product knowledge, (i.e., whether they are

experts or novices) [2,12,37]. Functional appeals are

likely to be effective for well-educated customers

because experts are able to infer all of the related

benets and thus nd technical description to be more

convincing. This is because experts are likely to

elaborate upon the message information by evaluat-

ing it in relation to their prior knowledge. Novices, on

the other hand, are likely to represent message

information more or less literally in memory or

feelings [17]. Because physical features may be mean-

ingless to novices, advertisements directed at novices

usually are structured around easily comprehended

benets [46].

Another concern of providing too much technical

information about novel products is that it may

induce the novice market to focus on what is not

known and thus may cause them to feel even greater

uncertainty. Prior research suggests that an unantici-

pated stimulus that violates existing cognitive struc-

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

9

tures is likely to generate high uncertainty since

individuals are likely to imagine alternative possible

scenarios and to create possible alternative explana-

tions for the particular stimulus [75]. Cognitive

response approach theory posits that people tend to

evaluate persuasive information based on their

existing knowledge about the topic [31]. We extend

this nding and assume that for less innovative

products, cases wherein customers have a depth of

knowledge about the product, they are more likely to

take a cognitive response approach and to evaluate

rationally the functional appeals offered in an ad. For

highly innovative products, when customers have

little product knowledge, they are more likely to take

an affect-based attitude to process the emotional

appeals rather than nonunderstandable functional

information.

Finally, overemphasizing functional information,

such as technological superiority, may lead to

miscommunication with customers. A common error

in innovation-driven ventures is that the rm usually

concerns itself with improved technologies rather

than with improved customer benets [66]. The reality

is that customers buy benets, not technologies. Most

consumers are not drawn to an innovative product by

its technological sophistication [34]. Therefore, the

communication objective of a highly innovative

product is not to emphasize whether the new techno-

ogy is superior to existing technology or not. Instead,

a more effective communication objective is to

persuade the customers that the new technology

provides a bundle of benets to them, such that they

are eager to abandon the older technology.

H2: Emotional ads (compared to functional ads) will

have a stronger positive impact on NPP when

innovativeness is higher than when it is low.

Controls

Figure 1 also shows a set of control variables

accounted for in the model. Market environmental

variables are designed to control features of market

competition that might serve as potential confounds

or alternative explanations for our hypotheses about

the relationship between communication strategies

and NPP [61]. Three market environmental variables

are adopted from the literature: Market Turbulence,

Technology Turbulence, and Competitive Intensity

[41]. These control variables are irrelevant to our

theoretical focus on the impact of communication

strategy on performance and the characteristics of

product innovativeness. However, previous studies

have shown that these environmental variables may

inuence NPP [13,41,60], thus we control these

variables in the regression models

1

.

Method

Data Collection

Survey respondents were product managers or

marketing managers that have been responsible for

at least one new product launch within the three years

prior to data collection. By new product we mean an

end product with an independently developed launch

strategy (e.g., a major release in which there was a

major change in the functionality of the product), not

a component of a product or a maintenance release

version. The respondent was asked to complete the

survey with respect to the most recent product launch

in which he or she had been involved.

The American Marketing Association (AMA)

membership list was used, and 3,742 pretested surveys

were sent out to product managers in the U.S. and

Canada. Among those, 30.4 percent of the surveys

were returned as undeliverable due to inaccuracies in

the mailing list. Of the remaining list, 67.5 percent of

the respondents were disqualied since they were not

product managers or since they had not launched a

product within the past three years. We had requested

these criteria on the questionnaire. This left 847 as the

qualied sample frame. Of these, 284 responded for

an effective response of 33.5 percent from the

qualied list. Demographic and other indicators

(including industry type) were compared for earlier

and later respondents. These results showed no

signicant differences, providing support for a lack

of nonresponse bias. A subsample of nonrespondents

was contacted to understand their rationale for not

responding. The vast majority indicated that they did

not have time.

Measurement

We developed the measures of the constructs in

several stages. In the rst stage, survey items were

1

Due to the page limits and the theoretical focus of this study, the

results of the interaction effects across various short-term and long-

term performances are summarized in Table 6, Table 7, and Table 8

[7,9,68]. The complete results of the main effects of the independent

variables as well as the control variables are available in [43].

10 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

generated either by borrowing directly from the

literature or through theoretical bases reected in

existing literature. In the second stage, a list of the

dened constructs and the measures were pretested on

ve academic experts. We asked the academic experts

to evaluate whether these measures were appropri-

ately representative of the constructs. In the third

stage, a focus group meeting was conducted for item

renement. In the meeting, ve product managers

were interviewed and were asked to comment on

the clarity and relevance of the measures. The items

were rened based on their comments. Finally, the

modied measures and constructs were pretested on

25 product managers. All the scales used in the pretest

were examined for reliability and unidimensionality

through the use of exploratory factor analysis. We

examined the item-to-total correlations for items in

each construct. We modied the measures by deleting

items with low correlations that did not represent an

additional domain of interest. The nal survey

contained measures of the key constructs and a set

of control variables. Tables 1 and 2 present the

measurement items for the key constructs, factor

loadings, and Cronbachs alpha coefcients. The

nalized items were subjected to maximum likelihood

factor analysis and were chosen based on high

loadings on a single factor with no signicant cross-

loadings.

Innovativeness. In the literature, innovativeness

typically is distinguished either by technology new-

ness and market newness [8,51] or by whether the

product is new to the rm or new to the world [10]. As

previously discussed, we believe there is a shortfall in

the literature dening innovativeness in that it does

not characterize explicitly and completely the full

dimensionality of innovation. The impact of product

innovativeness to the producers will be different from

that to the consumers, thus creating differences in the

effectiveness of launch strategies on performance. In

order to capture this effect, we specify these and

measure innovativeness along dimensions that are

important to producers and to consumers separately.

From the producers side, innovativeness refers to

the degree of newness of a product to the rm, in

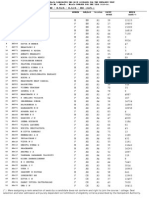

Table 1. Factor Analysis of the Independent and Moderator Variables

Independent Variables Measure Items

Factor Loading

(Cronbachs a)*

Advertising strategy Functional Ad

1. Emphasized the technology superiority 0.682

2. Provided detailed information about product attributes 0.780

3. Emphasized the rms technology competence 0.710

4. Persuaded customers by functional appeals (e.g., quality, economy, value, etc.) 0.734

Emotional Ad (0.713)

1. Evoked customers positive feelings of using this product 0.872

2. Persuaded customers by emotional appeals (e.g., joy, humor, love, pride, etc.) 0.872

(0.538)*

Innovativeness:

1. Product newness to the a. This product is a repositioning of an existing product. 0.867

rm b. This product is an updated version of an existing product. 0.867

(0.522)*

2. Market newness to the rm a. The market this product was introduced into was new. 0.800

b. The competition faced was new. 0.779

c. The new distribution channels needed for this product were new. 0.717

(0.644)

3. Product superiority to the a. The technology this product incorporates was new to the customers. 0.803

customer b. The benets this product offers were new to the customers. 0.822

c. Customers perceived the product features as novel/unique. 0.810

d. This product introduced many completely new features to the market. 0.807

e. This product offers dramatic improvements in existing product features. 0.657

(0.840)

4. Adoption difculty to the a. The knowledge required to use this product was new to the customers. 0.838

customer b. Customers needed to learn how to use this new product. 0.901

c. Customer tended to resist adopting this new product. 0.734

d. Customers needed to change their behavior in order to adopt this product. 0.864

(0.857)

* Correlation coefcients are reported for two-item constructs.

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

11

terms of the technology used [8,10,42,52,74,79], the

relationship of the new product to products typically

offered by the rm [25], and the degree to which

current markets are strayed from as targets for the

innovation [8,50]. To the extent that new markets or

undeveloped markets are targeted, new market

research methods, new distribution channels, and

new customer development approaches will be

required [8,10,52,53,74,79]. Based on the literature,

we identify product newness to the rm and market

newness to the rm as two dimensions of innovative-

ness from the producers perspective.

From the consumers side, product innovativeness

refers to the degree of novelty of the products

features/functionality/benets [4], degree of change

required in consumption behavior [4,6,77], and effort

required to learn to use and to adopt the new product

[6,49,77,78]. Answeaon (1988) considers the magni-

tude of the major change in the benets offered to the

consumers and the behavior change required to use

the product [4]. Similarly, Atuahene-Gima (1996)

refers to innovation newness as the degree to which

the new products usage patterns vary from current

customer consumption requirements and experiences

[6]. Veryzer (1998) investigates key factors affecting

customer evaluation of discontinuous new products.

He views product innovation as changes in three

dimensions. The consumption pattern dimension

refers to the degree of change required in the

thinking and behavior of the consumer in using the

product [77, p. 138].

Drawing from this literature, we distinguish the

impact of innovativeness on consumers into two

dimensions: product superiority to the customer and

adoption difculty to the customer. When facing a new

technology, consumers may experience a variety of

paradoxes [49]. Consumers simultaneously experience

both positive perceptions (innovativeness and opti-

mism) and negative perceptions (discomfort and

insecurity) regarding new technologies [54].

The innovativeness scales that resulted after

modication required by the pretest were four scales

that were derived from a set of 16 items that assessed

the newness associated with producers issues and

the newness associated with consumers issues.

Maximum likelihood factor analysis conrmed that

the Likert scale had four dimensions as we expected:

(1) product newness to the rm; (2) market newness

to the rm; (3) product superiority to the consumer;

and (4) adoption difculty to the consumer. The

details of the factor loading and Cronbachs alpha

coefcients are presented in Table 1.

Note that our respondents are product/brand/

marketing managers but not consumers. We believe

that based on their marketing research and interac-

tions with customers, managers have reliable data on

how customers perceive their products. Similar

measurement approaches have been used in previous

work. Andrews and Smith (1996) measured mean-

ingfulness of an innovation (referring to the extent to

which the marketing initiatives are thought to be

attractive or valuable to the consumers or retailers)

Table 2. Factor Analysis of the Control Variables

Control Variables Measure Items

Factor Loading

(Cronbachs a)

Competition Intensity 1. Number of competitors 0.716

2. The intensity of price competition 0.747

3. The competitive intensity in this industry 0.808

4. Strength of major competitors distribution system 0.725

5. Strength of major competitors distribution system 0.710

6. Strength of major competitors advertising 0.708

(0.833)

Market Turbulence 1. Degree of market turbulence that exists 0.736

2. Frequency of changes in customer preferences 0.826

3. Frequency of changes in customers needs 0.760

4. The extent to which the product life cycle shortens 0.642

(0.730)

Technology Turbulence 1. Degree of technology turbulence in the market 0.848

2. The extent of investment in technology development among competitors 0.823

3. Number of new technologies introduced in the market 0.900

4. Number of new product ideas make possible through technological breakthroughs

in our industry

0.848

(0.877)

12 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

from consumer goods product managers [5]. Veryzer

(1998) investigated key factors affecting customers

evaluation of discontinuous new products based on

project managers self-reports [77]. Recent empirical

work has demonstrated that the judgment of the

project manager about new product innovativeness

reliably reects that of consumers [67]. The author

reported a signicantly positive correlation (r5.75,

Po.01) suggesting a reasonably high match between

the two groups. This result supports the use of

managers ratings of new product innovativeness as

reasonable measures.

Performance Measures. NPP is measured on

multiple dimensions adopted from literature

[19,20,27,29,38], summarized in Table 3. Respondents

were asked to evaluate their products performance

on 12 items on a ve-point Likert scale with 1 being

Far below Expectations and 5 being Far above

Expectations. Previous empirical work has demon-

strated that the importance or priority of perfor-

mance objectives varies by the stages of the product

life cycle (PLC) [39]. Thus each performance objective

is evaluated at two time frames

2

: the short term

during the introduction and growth phase of the

product life cycle, when sales volume is growing; and

the long termonce the product has reached the

mature phase of product life cycle, when sales have

leveled off.

The results of exploratory factor analysis on the

ve performance measures are presented in Table 4.

The factor loadings for each construct of short-term

performance measures are greater than .87 and the

Cronbachs alpha coefcients for the ve constructs

are greater than or equal to .725.

Advertising Strategy. Building on the ELM [55], we

identify two types of advertising strategies based on

the message appeal. Functional Ad refers to an

advertising strategy that uses rational appeals to

demonstrate the objective and functional product

attributes (utilitarian benets) of the product. This

type of ad is usually informational-, factual-, or

thinking-oriented [36,47]. Emotional Ad refers to an

advertising strategy that uses emotional appeals to

demonstrate the subjective and symbolic benets

(hedonic benets) of the product. Emotional ads are

usually more emotional-, evaluative-, transforma-

tional-, or feeling-oriented [36,47]. The results of

factor analysis on the measures of advertising strategy

are presented in Table 1.

Preannouncement Strategy. The preannouncement

strategy refers to the formal, deliberate communica-

tion a rm engages in before it actually introduces a

new product into the market [24,63]. The rationale

and benets of applying a preannouncement strategy

can be illustrated from two perspectivesone per-

taining to a competitive behavior signaling rationale

and the other to a consumer behavior signaling

rationale. A preannouncement signal directed at

competitors usually is sent with the purpose of

inuencing competitive behavior [63] in order to

strengthen the rst-mover advantage [24].

Preannouncements to customers, on the other

hand, are articulated to achieve very different

purposes. Preannouncing a new product with the

intent to educate the customer would be advanta-

geous if the product requires substantial learning and

usage pattern adaptation on the consumers part [24].

Preannoucements directed at consumers can be used

effectively not only to reassure customers and to

Table 3. Operational Denition of Dependent Variables

Variable Operational Denition Relevant Reference

General Market

Performance

Market share performance Protability performance

Customer satisfaction

[19,29,38]

Extension to New Market The extent to which the product opens a window of

opportunity on a new market for the rm.

[19]

Extension to New Product

Class

The extent to which the product opens a window of

opportunity on a new category of products for the rm.

[19]

Market Penetration Rate The ratio of volume of sales to the total potential market. [27]

2

In order to ensure that respondents were not hampered by history

bias, we required that the new product they were referring to in their

responses must have been launched within the last three years. Some

products had not yet reached the mature stage of the PLC. Thus, the

sample sizes for short-term and long-term performance regressions are

not equal. On average, the sample size of the long-term performance

regressions is only around 50 percent of the size for the short-term

measures.

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

13

create a stable image for the company [59] but also to

encourage purchasing by creating anticipation of the

coming new product [48]. Building on previous

research, we identify three types of preannouncement

strategies based on the content of the message: market

preemption preannouncement, customer education pre-

announcement, and anticipation creation preannounce-

ment. The factor loadings and Cronbachs a are

presented in Table 5.

Results of Tests for Moderators

The main effect model tests the results of regressing

the changes in communication strategies on the

changes in NPP. The contingent model with interac-

tion terms examines the changes in the relationships

between communication strategy and performance

with the four dimensions of innovativeness

3

.

The results of the moderating role of innovative-

ness on the link between communication strategy and

performance are as follows.

Preannouncement Strategy

The rst conceptualization of innovativeness, product

newness to the rm, does not moderate the impact of

preannouncing (whether or not to preannounce) on

performance (see Table 6). When we look at the

dimension of innovativeness characterized by market

newness to the rm, preannouncing (compared to not

preannouncing) is associated with higher performance

on market penetration rate (b50.36, Po0.01), and

marginally better performance on short-term custo-

mer satisfaction (b50.30, Po0.10) and long-term

protability (b50.36, Po0.10). However, on two

dimensions of innovativeness associated with custo-

mers perception of innovativenessproduct super-

iority to the customer and adoption difculty for the

customerwe nd some counter-intuitive results: (1)

Preannouncing is associated with decreasing market

penetration rates as the degree of product superiority

increases (b50.27); and (2) Preannouncing is

associated negatively with short-term market exten-

sion (b50.28, Po0.10) and long-term protability

performance (b50.36, Po0.10) at marginally sig-

nicant levels.

These ndings are different from our expectation

that the more customers need to learn and change

Table 4. Factor Analysis of Dependent Variables

Factor Loading (Cronbachs a)*

Dependent Variables Measure Items Short term Long term

General Market Market Share-Related Performance

Performance 1. Market share performance 0.899 0.745

2. Volume sales performance 0.929 0.771

3. Rate of market penetration 0.922 0.763

(0.905) (0.868)

Protability-Related Performance

1. Net prots margin 0.918 0.893

2. Gross prots margin 0.934 0.906

3. Return on investment 0.870 0.794

(0.886) (0.911)

Customer Satisfaction-Related Performance

1. Customer satisfaction 0.908 0.895

2. Customer loyalty 0.908 0.905

(0.651)* (0.743)*

Market Extension-Related Performance

1. Extension into new markets 0.909 0.865

2. Extension into new product categories 0.909 0.900

(0.651)* (0.610)*

Market Penetration Rate 1. Market penetration rate compared to rm objective 0.886

2. Market penetration rate compared to major competitors 0.886

(0.575)*

* Correlation coefcients are reported for two-item constructs.

3

Due to space limitations and the purpose of this study, we present

the results of the coefcients of the interaction terms only. Main effect

results can be obtained from the rst author.

14 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

their behavior to adopt the new product, the more

likely it is that customers will appreciate the

preannouncement. To further investigate these coun-

ter-intuitive results, we investigated the nature of the

message delivered to customers in the preannounce-

ment. Therefore, a set of contingent regression

models with the interaction terms of three types of

preannouncement objectives or messages is tested.

The three types of preannouncement objectives are

customer education, anticipation creation, and market

preemption.

Customer education refers to a message that

describes the functionality of the product and

creates a sense of familiarity with it. The focus of

the message is on the product and how to use it.

Anticipation creation refers to a message that builds

momentum and demand for the product by heighten-

ing expectations of it and encouraging people to talk

about it. Finally, market preemption refers to a

message whose objective is to discourage competitors

from entering the market. Results of the regressions

(see Table 7) indicate that preannouncements empha-

sizing customer education lead to higher performance

for products that are difcult to adopt. When the

product requires a lot of learning effort and behavior

changes for the customer, customer education-

oriented preannouncements are associated with

higher market penetration rates (b50.22, Po 0.01),

and marginally positively are associated with both

short-term market share (b50.20, Po0.10) and long-

term market share (b50.28, Po0.10) (Table 7). The

empirical results demonstrate that customers

respond more to educational preannouncements

over the other two types of preannouncement

when they face a product that is very difcult to

adopt.

Table 5. Factor Analysis of Preannouncement Strategy

Independent Variables Measure Items Factor Loading

(Cronbachs a)*

Preannouncement Strategy Content of the Preannounced Message

A. Customer Education

1. Educate the customers about this product 0.743

2. Make customers more familiar with this product 0.728

3. Make customers more comfortable with the incorporated technology 0.743

4. Reduce customers resistance to this product 0.814

5. Reduce customers risk perception of this product 0.775

(0.820)

B. Anticipation Creation

1. Encourage potential customers to talk about our products 0.770

2. Make sales accelerate more rapidly when you introduce the product 0.632

3. Increase customers expectations of our products introduction 0.765

4. Begin building customer awareness 0.675

(0.670)

C. Market Preemption

1. Discourage competitors from introducing this type of product 0.880

2. Make it difcult for competitors to enter successfully 0.880

(0.591)*

* Correlation coefcients are reported for two-item constructs.

Table 6. Results of the Tests of the Impact of Innovativeness (four dimensions) on the Relationship between

Preannouncement Strategy (whether preannounce or not) and Performance

The Impact of Innovativeness to the Producer

Product newness to the rm Market newness to the rm

market penetration rate (b50.36*** )

customer satisfaction (S) (b50.30* )

customer satisfaction (L) (b50.36*)

The Impact of Innovativeness to the Consumer

Product superiority to the customer Adoption difculty to the customer

market penetration rate (b50.27**) market extension (b50.28*)

protability (L) (b50.36*)

*po0.1

**po0.05

***po0.01

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

15

On the other hand, a preannouncement message

that focuses on creating anticipation for the coming

new product leads to higher performance for products

that provide high superiority to customers. Highly

superior products are unique and have clear advan-

tages over other known products. Therefore, a high

anticipation-oriented preannouncement leads to mar-

ginally greater customer satisfaction (b50.26,

po0.10) for such unique products because, we would

theorize, their expectations ultimately are met.

The results also indicate that preannouncement

messages with the objective of market preemption are

not appropriate for products that are new to the rm.

Market preemption-oriented preannouncements are

associated negatively with market penetration rate

(b50.24, Po0.05) and short-term market share

(b50.26, Po0.01) for new-to-the-rm products.

Products that are new to the rm are not necessarily

very innovative or unique to the marketplace. A

possible explanation of this negative moderating

effect is that preannouncing may provide signals to

competitors who are already active in those product-

market arenas, giving them time to react. For new-to-

the-rm products, preannouncing with market pre-

emption messages does not create preemption ad-

vantage, and, on the contrary, may raise severe

reactions from incumbents. Moreover, market pre-

emption-oriented preannouncements are associated

with lower customer satisfaction performance for

both products introduced to unfamiliar markets

(b50.23, Po0.10, marginally signicant) and for

highly superior products (b50.23, Po0.01). The

insight of these ndings is that in considering

preannouncement message strategy, ghting against

competitors (a market preemption message) is a less

effective path to increased performance than is

pleasing customers (via customer education or

anticipation creation messages).

Advertising Strategy

The relationship between advertising strategy and

NPP is consistent for both measures of innovativeness

from the producers perspective: the degree of

product newness to the rm and the degree of market

newness to the rm. However, on the dimension of

innovativeness characterized by product superiority

to the customer, if the products are perceived as

unique, novel, or superior, functional ads are

associated with higher short-term protability

(b50.36, Po0.10) than are emotional ads. This result

is marginally signicant (Table 8).

On the contrary, however, adoption difculty to

the customer negatively moderates the relationship

between advertising strategy and NPP as measured by

extensions into new market segments. When the

product requires a lot learning effort or behavior

changes on the part of the customer, functional ads

may decrease market extension performance

(b50.65, Po0.01).

The impact of advertising strategy on NPP is

moderated by innovativeness only when we look at

the dimensions associated with innovativeness to the

Table 7. Results of the Tests of the Impact of Innovativeness (four dimensions) on the Relationship between

Preannouncement Strategy (the Nature of the Message Preannounced) and Performance

Preannounced Message

Product Newness

to the Firm

Market Newness

to the Firm

Product Superiority

to the Customer

Adoption Difculty

to the Customer

Customer Education Mkt Pen. Rate

(b50.22*** )

Mkt Share (S)

(b50.20* )

Mkt Share (L)

(b50.28* )

Anticipation Creation Cus. Sat. (L) (b50.26*)

Mkt Ext. (L) (b50.25* )

Market Preemption Mkt. Pen. Rate

(b50.24**)

Cus. Sat. (L)

(b50.23* )

Cus. Sat. (S)

(b50.23***)

Mkt. Share (S)

(b50.26***)

*po0.1

**po0.05

***po0.01

16 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

customers but not when we look at the dimensions

associated with innovativeness to the rm. Advertis-

ing strategy that impacts on performance differs

depending on how customers perceive the innova-

tioneither as providing product superiority to the

customer or as highly difculty to adopt.

When the product has clear advantages over other

known products and has superior benets to custo-

mers, functional ads lead to higher performance.

However, if the product requires that customers learn

a lot or change their consumption behavior, then

emotional ads lead to higher performance. The

possible explanation is that functional ads emphasize

the features of the products and clearly communicate

how this product is superior over other previous

products. Emotional ads, on the other hand, focus on

how this product ts customers needs. Emotional ads

skip all the technical details and emphasize the

benets to the customers to evoke their positive

feelings for trying the new product. If a product is

very innovative in a way that customers need to learn

a lot and change their consumption patterns, then

functional ads focusing on technical details may not

be appropriate because customers do not have the

knowledge to evaluate such technical information.

Rather, emotional ads focusing on the benets of the

innovation are more attractive to customers if the

product is very difcult to adopt.

Conclusions and Managerial Implications

Summarizing the results of this research, there are

several interesting ndings that have academic con-

tributions as well as potential managerial implica-

tions. First, the relationships between each

communication strategy and each dimension of

performance differ not only by degree of innovative-

ness but also by the dimension of innovativeness. The

insight of this nding is that innovativeness needs to

be measured on multiple dimensions. Oversimplifying

or aggregating the measures of innovativeness may

estimate incorrectly the impact of innovativeness on

launching a new product.

These results indicate that the links between

communication strategies and various conditions of

innovativeness differ. With respect to preannounce-

ment strategy, when customers perceive that the

product will require a lot of learning effort, a

customer education-oriented message is the prean-

nouncement tool most tightly linked with positive

NPP. However, if the product is perceived by

customers as providing superior quality or utility,

then anticipation creation-oriented preannouncement

messages outperform the other two types of pre-

announcement message strategies.

With respect to advertising strategies during

launch, the positive impact of emotional ads on NPP

increases with the degree of the adoption difculty of

the product perceived by the customers. On the other

hand, the positive relationship between functional ads

and NPP will become stronger as the degree of

product superiority increases.

Second, the relationships between the communica-

tion strategies available to the product manager and

performance are moderated the most by the two

dimensions of innovativeness associated with custo-

mers: product superiority to the customer and

Table 8. Summary of the Results of the Moderating Role of Innovativeness on the Relationship between Advertising

Strategy and Performance

The Impact of Innovativeness to the Producer

The impact of advertising strategy to NPP is NOT moderated by innovativeness associated with the rm:

1. Product newness to the rm

2. Market newness to the rm

The Impact of Innovativeness to the Consumer

The impact of adverting strategy to NPP is moderated by innovativeness associated with consumers:

1. Product superiority to the customer (b50.36* ) - Functional ads lead to higher protability than do emotional

ads, if customers perceive the product as unique, novel, and

superior compared to existing offers.

2. Adoption difculty to the customer (b50.65** ) - Emotional ads lead to higher market extension performance

than do functional ads, when the product requires a lot of

learning efforts or behavior changes on the part of consumers.

* po0.1

** po0.05

*** po0.01

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNICATION STRATEGY J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

17

adoption difculty for the customer. This nding

supports our argument that measuring innovativeness

by technological uncertainty and market uncertainty

alone or by the Booz, Allen, and Hamilton typology

[10] does not give enough information to examine the

impact of innovativeness on launch strategies. We

suggest that innovativeness needs to be measured with

the producer and consumer dimensionality clearly

specied because the meaning of the term differs for

each perspective.

Third, among the four dimensions of innovative-

ness, product newness to the rm does not have much

signicant impact on the relationship between launch

strategy and performance. Many previous studies

have measured innovativeness, at least in part, on this

dimension. Our results suggest that, at least where

launch strategies are concerned, misinterpretations of

the effects of innovativeness on launching new

products may result from measuring innovativeness

as newness to the rm.

Fourth, the interaction results of adoption dif-

culty for the customer are different from the

interaction effects of the other three dimensions of

innovativeness. The possible reason is that, different

from other three dimensions of innovativeness,

adoption difculty for the customer may be perceived

by customers as negative information, meaning high

risk, high uncertainty, and high switching costs.

Therefore, the communication strategies for products

with high adoption difculty differ from those for the

other three dimensions of innovative products. Again,

this nding supports our argument that innovative-

ness measures that do not incorporate consumers

perspectives are incomplete, because the consumption

behaviors may change depending on customers

perception of the innovativeness, and that change is

associated with the impact of communication strate-

gies on NPP.

Finally, some strategies may receive immediate

reactions from the market, while others have delay

effects. For example, a hostile signal with the intent to

preempt the market is more likely to garner im-

mediate reactions from competitors. The negative

effects of these strong competitive reactions may

cause a loss of market share and the reduction of

market penetration in the short term. However, it

may take a longer time for anticipation creation

preannouncement messages to be effective. Signaling

the product superiority or uniqueness to the con-

sumer with the intent to create a positive feeling for

the forthcoming new product may increase customer

satisfaction. This positive effect is signicant in the

long term but not in the short term, according to the

data reported here.

Potential Limitations and Future Research

Issues

Some researchers have expressed concern about the

potential bias of using single informants in data

collection [56]. Although our study uses a single

informant approach, we believe that this approach is

appropriate for several reasons. First, because our

research objective focuses on investigating various

types of communication strategies applied to each

new product, using product managers who are fully in

charge of the launch of the new product seems

warranted. These informants were selected carefully

for their unique expertise [14]. Second, Grifn (1993)

measured the reliability of single informants for most

new product development studies. The estimates

provided by individual informants are surprisingly

robustthey usually fall within ve10 percent of

each other (p. 120) [28].

A related limitation is that we measured the

impacts of innovativeness on consumers based on

the perceptions of product managers rather than by

directly surveying consumers. Any bias that product

managers might incorporate would, we expect,

weaken our results. Accounts from consumers, to

the extent that they vary at all, would cause our

results to be stronger than reported here. The effect of

the differences, however, has been shown in the

literature to be small enough so as not to affect the

outcomes of the analysis. Sethi (2001) demonstrates

that there are no signicant differences between the

judgment of the project manager about product

innovativeness and that of consumers [67].

It also should be noted that consumers percep-

tions of product innovativeness likely are affected by

many endogenous and exogenous factors, such as

personality, level of product knowledge, experiences

of similar products, pressure from social norms, and

other factors. These behavior-related issues fall out-

side the theoretical focus of this study. The major

purpose of this study is to investigate the most

appropriate or effective communication strategies

under different conditions of product innovativeness.

We are interested in the average or overall rating of

product innovativeness in the marketplace as a guide

for designing communication strategies for the new

18 J PROD INNOV MANAG

2003;20:421

Y. LEE AND G.C. OCONNOR

product. In this case, it is more effective to collect

data from product managers who have general ideas

(based on their marketing research and interactions

with customers) of whether customers like or dislike

the product than from the individual customer. An

important area for future research is the need to

measure product innovativeness perceptions in this

dyad fashion to understand where, why, and how big

the gaps are in perceptions between producers and

consumers with respect to innovativeness and how

this impacts management of new product launches.

As a nal limitation, the sample is not representa-

tive of the population of all businesses. Though the

sample covers multiple industries, the data is collected

based on a convenience sample of product/brand/

marketing managers that participate in the AMA.

The fact that we exclude potential respondents that

are not the members of AMA may affect the

generalizability of this study.

In this article we have demonstrated empirically

that the impact of communications strategy on NPP

is moderated by product innovativeness and that the

conceptualization and measurement of innovativeness

is critically important in determining appropriate

strategies for success. We have built on the emerging

work that is dening innovativeness conceptually

along these various dimensions, [25,49,77] and have

shown how important it is in academic relevance and

managerial practice.

References

1. Abernathy, W.J. and Clark, K.B. Innovation: mapping the winds

of creative destruction. Research Policy 14:322 (1985).

2. Alba, J.W. and Marmorstein, H. The effects of frequency

knowledge on consumer decision-making. Journal of Consumer

Research 14(June):1425 (1987).

3. Ali, A. and Krapfel Jr., R., et al., Product innovativeness and

entry strategy: impact on cycle time and break-even time. Journal

of Product Innovation Management 12:5469 (1995).

4. Anderson, R.L. and Ortinaa, D.J. Exploring consumers post-

adoption attitudes and use behaviors in monitoring the diffusion

of a technology-based discontinuous innovation. Journal of

Business Research 17:283298 (1988).

5. Andrews, J. and Smith, D.C. In search of the marketing

imagination: factors affecting the creativity of marketing programs

for mature products. Journal of Marketing Research 33(May):174

187 (1996).

6. Atuahene-Gima, K Differential potency of factors affecting

innovation performance in manufacturing and services rms in

Australia. Journal of Product Innovation Management 13:3552

(1996).

7. Baron, R.J. and Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable

distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic,

and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology 51(6):11731182 (1986).

8. Beard, C. and Easingwood, C. New product launch: marketing

action and launch tactics for high-technology products. Journal of

Marketing Management 25(2):87103 (1996).

9. Becherer, R.C. and Maurer, J.G. The moderating effect of

environmental variables on the entrepreneurial and marketing

orientation of entrepreneur-led rms. Entrepreneurship Theory and

Practice 22(1), 4758 (1997).

10. Booz, A. and Hamilton, I. New Product Management for the

1980s. New York: Booz, Allen, and Hamilton, Inc., 1982.

11. Brown, R. Managing the S curves of innovation. Journal of

Consumer Marketing 9(1):6172 (1992).

12. Cacioppo, J.T. and Petty, R.E., et al. Effects of need for cognition

on message evaluation, recall, and persuasion. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology 45:805818 (1983).

13. Calantone, R. and Schmidt, J.B., et al. New product activities and

performance: the moderating role of environmental hostility.

Journal of Product Innovation Management 14(3):179189 (1997).

14. Campbell, D.T. The informant in quantitative research. American

Journal of Sociology 60(January):339342 (1955).

15. Campbell, T. Back in focus. Sales and Marketing Management

151(2):5661 (1999).

16. Chandy, R. and Tellis, G.J. et al. What to say when: advertising

appeals in evolving markets. Marketing Science Institute working

paper #01-103 (2001).

17. Chi, M. and Feltovich, P.J. et al. Categorization and representa-

tion of physics problems by experts and novices. Cognitive Science

5(April):121152 (1981).

18. Cooper, R.G. and Brentani, U.D. New industrial nancial

services: what distinguishes the winners. Journal of Product

Innovation Management 8:7590 (1991).

19. Cooper, R.G. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. New product success factors:

a comparison of kills versus successes and failures. R&D

Management 20(1):4763 (1990).

20. Cooper, R.G. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. Determinants of timeliness

in product development. Journal of Product Innovation Manage-

ment 11:381396 (1994).

21. Dhebar, A. Speeding high-tech producer, meet the balking

consumer. Sloan Management Review 37(2):3749 (1996).

22. Dougherty, D Understanding new markets for new products.

Strategic Management Journal 11:5978 (1990).

23. Ehrnberg, E. On the denition and measurement of technological

discontinuities. Technovation 15(7):437452 (1995).

24. Eliashberg, J. and Robertson, T.S. New product preannouncing

behavior: a market signaling study. Journal of Marketing Research

24(August):282292 (1988).

25. Garcia, R. and Calantone, R. A critical look at technological

innovation typology and innovativeness terminology: a literature

review. Journal of Product Innovation Management Forthcoming

(2001).

26. Goldenberg, J. and Lehmann, D.R., et al. The idea itself and the