Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gardner v. Detroit Entertainment

Uploaded by

eric_meyer8174Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gardner v. Detroit Entertainment

Uploaded by

eric_meyer8174Copyright:

Available Formats

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

SUMMER GARDNER,

Plaintiff, Case No. 12-14870

HON. TERRENCE G. BERG

v.

DETROIT ENTERTAINMENT, LLC,

d/b/a MOTORCITY CASINO,

a Michigan limited liability company,

Defendant.

____________________________________/

OPINION AND ORDER DENYING DEFENDANTS

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT (DKT. 25)

In this case, a former casino employee claims that she was fired in violation

of the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Plaintiff Summer Gardner (Plaintiff)

is a former employee of Defendant Detroit Entertainment, LLC d/b/a Motorcity

Casino (Defendant). Plaintiff claims Defendant interfered with her FMLA

benefits by denying those to which she was entitled.

Defendant now moves for summary (Dkt. 25), Plaintiff has responded (Dkt.

29), and Defendant replied (Dkt. 31). On June 23, 2014, the Court heard oral

argument on Defendants motion. For the reasons set forth below, Defendants

motion for summary judgment is DENIED.

I. BACKGROUND

At the outset, the Court notes Defendant did not follow the Courts practice

guidelines in its motion for summary judgment. The Courts practice guidelines for

2

motions for summary judgment are available on the Courts website

1

and provide as

follows:

A Rule 56 motion must begin with a Statement of Material Facts. Such a

Statement is to be included as the first section of the Rule 56 Motion. The

Statement must consist of separately numbered paragraphs briefly

describing the material facts underlying the motion, sufficient to support

judgment. Proffered facts must be supported with citations to the pleadings,

interrogatories, admissions, depositions, affidavits, or documentary exhibits.

Citations should contain page and line references, as appropriate.... The

Statement of Material Facts counts against the page limit for the brief. No

separate narrative facts section shall be permitted.

The response to a Rule 56 Motion must begin with a Counter-statement of Material

Facts stating which facts are admitted and which are contested. The paragraph

numbering must correspond to moving partys Statement of Material Facts. If any

of the moving partys proffered facts are contested, the non-moving party must

explain the basis for the factual disagreement, referencing and citing record

evidence. Any proffered fact in the movants Statement of Material Facts that is not

specifically contested will, for the purpose of the motion, be deemed admitted. In

similar form, the counter-statement may also include additional facts, disputed or

undisputed, that require a denial of the motion.

Defendants motion for summary judgment did not comply with the Courts

practice guidelines, as it did not provide an enumerated list of Material Facts,

with specific citations to the record. Rather, Defendants brief contains a narrative

fact section, which is expressly prohibited by the Courts practice guidelines.

Consequently, Plaintiffs response brief could not offer a Counter-statement

to Defendants motion. Without such competing statements of material facts, it is

1

http://www.mied.uscourts.gov/PDFFIles/BergPracticeGuidelines.pdf

3

difficult to discern which facts are, and are not, subject to dispute. Both counsel are

advised that failure to follow the Courts practice guidelines in the future will result

in their pleadings being stricken from the record. In any event, the Court conducted

a very thorough review of the parties briefs, oral arguments, and exhibits and

gleaned the following facts, which are viewed in a light most favorable to the

Plaintiff as the non-moving party.

Plaintiff began working for MotorCity Casino on November 8, 1999 (Dkt. 29,

Ex. B, Gardner Dep., p. 17). In June, 2004, Plaintiff first sought FMLA protected

leave (Dkt. 29, Ex. C, 6). Throughout the following seven years, Plaintiff was on

and off intermittent medical leave for various reasons. Id. The first period of

intermittent leave related to Plaintiffs current medical condition began in June

2006 (Dkt. 29, Ex. C, 7). At that time, Plaintiff was approved for intermittent

FMLA leave related to a degenerative spinal disorder (Dkt. 29, Ex. B, Gardner Dep.,

p. 27). This disorder left Plaintiff unable to work after working on her feet for

several days in a row (Dkt. 29, Ex. C, 5). Between June 2006 and July 2011,

Plaintiff was approved for periods of intermittent leave related to this disorder

seven separate times (Dkt. 29, Ex. C, 7; Dkt. 29, Ex. E).

The specific period of intermittent FMLA leave at issue in this case began on

July 1, 2011 (Dkt. 1, 8; Dkt. 29, Ex. E). During the first ten years of Plaintiffs

employment, Defendant processed FMLA leave requests internally through its

Human Resources Department (Dkt. 25, p. 2). However, beginning in October of

2009, Defendant retained a third party administrator, FMLASource, to process

4

FMLA leave requests. Id. Plaintiff contends that she informed FMLASource she

wished to be communicated with by postal mail regarding FMLA-related

communications (Dkt. 29, Ex C, Gardner Decl., at 10-12). The relevance of this

fact becomes apparent below. During the time between November 2009 and

December 2011, Plaintiff received numerous letters from FMLASource through

postal mail (Dkt. 29, Ex. E).

In October 2011, Defendant and FMLASource became aware that Plaintiff

had been absent on intermittent FMLA leave nine times in September 2011, five

more than anticipated by her doctor, and that she also had called off work every

Sunday in September 2011 (Dkt. 25, Ex. G, Sue Depo. at 15; Ex. E, Cluff Depo. at

48). Accordingly, on October 7, 2011 FMLASource sent a letter via email to

Plaintiff, requesting that her health care professional re-certify the basis for her

leave by October 25, 2011 (Dkt. 25, Ex. L, Recertification Email). Whether this

email constituted sufficient notice to Plaintiff is a central issue to this case.

Plaintiff contends that she did not open, and therefore did not effectively receive the

October 7, 2011 email, in time to respond by the October 25, 2011 deadline. Again,

prior to this critical email, Plaintiff contends that FMLASource communicated with

her regularly through postal mail (Dkt. 29, Ex. E).

Not having opened this email, Plaintiff did not submit the recertification

paperwork by October 25, 2011. FMLASource then automatically generated another

letter on October 27, 2011, and sent it to Plaintiff again by email, advising her that

due to the lack of recertification documentation, her intermittent leave was now

5

only approved from July 1, 2011 to October 6, 2011, and that her leave request for

the period from October 7, 2011 to December 12, 2011 was denied (Dkt. 25, Ex. J;

Ex. M).

Defendant thus contends that any absences after October 6, 2011 occurred

outside of the protections afforded by the FMLA, and became subject to the normal

consequences of Defendants attendance policy (Dkt. 25, Ex. M; Ex. J). Before this

time, Plaintiff had accumulated 3.5 attendance points, for non-FMLA-protected

absences which occurred on July 15, 2011, August 6, 2011 and September 17, 2011

(Dkt. 25, Ex. O; Ex. P, Gardner Depo. at 33-34). In addition to those unprotected

absences, Plaintiff had also been absent on October 22, 23, 28, 29 and November 2,

2011, which she had designated as covered by her intermittent FMLA leave (Dkt.

25, Ex. Q; Ex. P, Gardner Depo. at 45). According to Defendant, Plaintiffs failure to

provide timely recertification from her health care professional of the basis for her

leave meant that those absences were not FMLA-protected.

On November 4, 2011, Leticia McCall, Defendants Human Resources staff

member who handled FMLA leave requests, informed Crystal Deault in Defendants

Slot Department that, because Plaintiffs intermittent FMLA leave request for the

period of October 7 to December 12, 2011 had been denied, any absences during

that period were now subject to Defendants attendance policy (Dkt. 25, Ex. R).

Treating all of Plaintiffs absences as unexcused under Defendants attendance

policy resulted in an accumulation of 8.5 attendance violation points between July

6

15, 2011 and November 2, 2011, subjecting Plaintiff to termination.

2

Defendant

decided to terminate Plaintiffs employment.

Plaintiff called FMLASource on November 7, 2011 and spoke with

Customer Service Specialist Adriana Sue. Ms. Sue memorialized the conversation

in a log entitled Notes for Summer Gardner either during or immediately after the

conversation (Dkt. 25, Ex. G, Sue Depo. at 24). The log entry for November 7, 2011

provides in pertinent part:

Employee stated that she was told by her employer that Intermittent Leave

recertification was denied. Employee stated that she did not know that

recertification was opened. Advised employee recertification was opened

because she used 9 absences in September and is only certified for 4 episodes

per month and she reported time off for every Sunday in September.

Employee stated that she never received paperwork. Advised employee

paperwork was sent to email provided in demographic information and

correspondence settings were set to email only. Employee stated that when

she opened claim, she authorized email only knowing that she was

expecting something but has not been checking email so did not know

recertification paperwork was sent. Advised employee that she gave

permission for email only so thats how paperwork was sent. Updated setting

to postal and email.

(Dkt. 25, Ex. H). Plaintiff disputes that she ever authorized FMLASource to send

correspondence to her via email only (Dkt. 29, Ex. C 10) (At no time did I

inform anyone at FMLASource that I should be communicated with by email only,

because I do not use email very often).

Plaintiff appealed the denial of her leave to FMLASource and submitted a

statement in support of the appeal (Dkt. 25, Ex. S). Plaintiff also submitted the

required paperwork from her doctor, on November 23, 2011 (Dkt. 29, Ex. J). Upon

2

Under Defendants attendance policy for hourly workers such as Plaintiff, an accumulation of seven

attendance points in a 180-day period is grounds for termination (Dkt. 25, Ex. C).

7

receipt of the required paperwork from Plaintiffs doctor, FMLASource approved

Plaintiffs FMLA leave, but only from November 22 to December 12, 2011. Id.

Defendant, and FMLASource, upheld the denial of Plaintiffs FMLA leave between

October 7 and November 21, 2011. Thus, Plaintiffs appeal was denied, and the

termination of her employment was final. Id.

Plaintiff then brought this lawsuit.

II. ANALYSIS

A. The Standard For Summary Judgment

Summary judgment is proper if the movant shows that there is no genuine

dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter

of law. See Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 56(a). A fact is material only if it might affect the

outcome of the case under the governing law. See Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.,

477 U.S. 242, 249 (1986). On a motion for summary judgment, the Court must view

the evidence, and any reasonable inferences drawn from the evidence, in the light

most favorable to the non-moving party. See Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith

Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 587 (1986) (citations omitted); Redding v. St. Edward,

241 F.3d 530, 531 (6th Cir. 2001).

The moving party has the initial burden of demonstrating an absence of a

genuine issue of material fact. See Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 325

(1986). If the moving party carries this burden, the party opposing the motion

must come forward with specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for

trial. Matsushita, 475 U.S. at 587. The Court must determine whether the

8

evidence presents a sufficient factual disagreement to require submission of the

challenged claims to a jury or whether the moving party must prevail as a matter of

law. See Anderson, 477 U.S. at 252 (The mere existence of a scintilla of evidence in

support of the plaintiffs position will be insufficient; there must be evidence on

which the jury could reasonably find for the plaintiff).

Moreover, the trial court is not required to search the entire record to

establish that it is bereft of a genuine issue of material fact. Street v. J.C. Bradford

& Co., 886 F.2d 1472, 147980 (6th Cir. 1989). Rather, the nonmoving party has

an affirmative duty to direct the courts attention to those specific portions of the

record upon which it seeks to rely to create a genuine issue of material fact. In re

Morris, 260 F.3d 654, 655 (6th Cir. 2001).

B. The Family Medical Leave Act

The Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) entitles eligible employees to take

reasonable leave for medical reasons, for the birth or adoption of a child, and for the

care of a child, spouse, or parent who has a serious health condition. 29 U.S.C

2601. In this case, Plaintiff sought leave for medical reasons. An employee is

eligible for FLMA-protected medical leave when the employees own serious health

condition makes the employee unable to perform the functions or his or her job.

See 29 C.F.R. 825.100(a) (2013). In order to provide eligible employees with

unfettered access to protected leave, the FMLA makes it unlawful for an employer

to interfere with, restrain, or deny the exercise of or the attempt to exercise, any

right provided [by the Act], or to discharge or in any other manner discriminate

9

against any individual for opposing any practice made unlawful by [the Act].

Seeger v. Cincinnati Bell Tel. Co., 681 F.3d 274, 281 (6th Cir. 2012) (citing 29 U.S.C.

2615(a)(1)-(2)).

The Sixth Circuit has recognized two theories of recovery under the FMLA:

(1) the interference or entitlement theory arising from 2615(a)(1), and (2) the

retaliation or discrimination theory arising from 2615(a)(2). Seeger, 681 F.3d at

882. The interference theory stems from the FMLAs creation of substantive rights,

while the retaliation theory considers whether an employer took an adverse action

for a prohibited reason. Id. Under the interference theory, an employee may

recover from an employer when a violation occurs, regardless of the employers

intent. Id. Conversely, under the retaliation theory, the employers motive is

relevant because retaliation claims impose liability on employers that act against

employees specifically because those employees invoked their FMLA rights. Id.

(quoting Edgar v. JAC Prods., Inc., 443 F.3d 501, 508 (6th Cir. 2006)) (original

emphasis).

Plaintiffs Complaint appears to raise both an FMLA interference claim and a

retaliation claim (Dkt. 1, 20 Defendant willfully violated the FMLA by

interfering with Plaintiffs attempt to take FMLA leave and/or retaliating against

Plaintiff for her exercise of her rights under the FMLA). However, the parties

summary judgment briefs appear to focus solely on an FMLA interference claim.

3

3

FMLA retaliation claims are evaluated according to the burden-shifting framework announced in

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973). Defendants motion for summary judgment

does not discuss the McDonnell Douglas burden-shifting analysis. Thus, to the extent that Plaintiffs

Complaint raises an FMLA retaliation claim, this claim also survives summary judgment.

10

C. Plaintiffs FMLA Interference Claim

To prevail on an FMLA interference claim, Plaintiff must establish five

things: (1) that she was an eligible employee, (2) that Defendant was an employer

as defined under the FMLA, (3) that Plaintiff was entitled to leave under the

FMLA, (4) that Plaintiff gave the employer notice of her intention to take leave, and

(5) that the employer denied the her FMLA benefits to which she was entitled. See

Edgar, 443 F.3d at 507. Here, the parties dispute only the fifth element.

Specifically, the issue is whether Defendant unlawfully denied Plaintiff FMLA

benefits to which she was entitled on October 22, 23, 28, 19, and November 2, 2011.

Defendant argues that, because Plaintiff failed to submit the recertification

paperwork FMLASource by October 25, 2011, Plaintiffs intermittent FMLA leave

expired on October 6, 2011. Thus, Defendant argues, Plaintiff was not entitled to

FMLA benefits on October 22, 23, 28, 19, and November 2, 2011. However, Plaintiff

claims that Defendants notice of its request for recertification was insufficient, and

for that reason Plaintiff was entitled to FMLA benefits through December 12, 2011,

as FMLASource previously approved her for intermittent FMLA leave through that

date (Dkt 29, Ex. E, Pg ID 362).

The FMLA allows an employer to require recertification from an employee

taking FMLA leave on a reasonable basis. 29 U.S.C. 1213(e). According to 29

C.F.R. 825.308, an employer may request recertification no more than every 30

days. 29 C.F.R. 825.308(a). And if the original certification indicates that the

minimum duration of the medical condition is more than 30 days, an employer

11

must wait until that minimum duration expires before requesting recertification.

Id. 824.308(b). However, an employer may request recertification in less than 30

days if the [c]ircumstances described by the previous certification have changed

significantly. Id. 825.308(c)(2). For instance, if the duration or frequency of the

absences increases beyond the estimate in the original certification, an employer

may request recertification. Id.

Defendant generally requires recertification every six months (Dkt. 25, Ex.

F). However, as 29 C.F.R. 825.308(c)(2) permits, Defendant generally requires

recertification more frequently [i]f the circumstances described in the original

medical certification have changed significantly or Human Resources receives

information that casts doubt upon the continuing validity of the medical

certification. Id. Defendant claims the recertification at issue in this case falls into

the latter category. Plaintiffs original certification, corresponding to the leave

period beginning July 1, 2011 and ending December 12, 2011, estimated that she

would accumulate four episodic incapacitations per month (Dkt. 25, Ex. K). Yet,

during the month of September, Plaintiff accumulated nine FMLA-protected

absences (Dkt. 25, Ex. G, Sue Dep., p. 15; Dkt. 25, Ex. E, Cluff Dep., p. 48). For that

reason, Defendant questioned the validity of Plaintiffs FMLA leave and

FMLASource then generated an email to Plaintiff that required Plaintiff to submit

recertification paperwork. There is no dispute in this case that Defendant had the

right to require Plaintiff to recertify her FMLA leave. The dispute revolves around

whether FMLASource gave Plaintiff proper notice of her need to recertify.

12

Specifically, the issue is whether Defendant (through FMLASource), by

informing Plaintiff of the recertification requirement via email, gave Plaintiff

proper notice of that requirement. [R]egardless of the circumstances under which

the FMLA permits an employer to demand medical verification that a particular

absence is properly counted as part of an approved FMLA leave, it seems evident

that the employer must . . . notify the employee of this requirement. McClain v.

Detroit Entertainment, L.L.C., 458 F.Supp.2d 427 (E.D. Mich. 2006). In fact, 29

C.F.R. 825.305, which governs certification generally, makes clear that an

employer must give notice of a requirement for certification each time certification

is required. See 29 C.F.R. 825.305(a). Whether an email is a sufficient means of

notification is less clear however. Regarding means of notification, 29 C.F.R.

825.305 provides that notice [of a certification requirement] must be written notice

whenever required by 825.300(c), and further that [a]n employers oral request

to an employee to furnish any subsequent certification is sufficient. Id.

Section 825.300(c) discusses an employers obligation to notify an FMLA-

eligible employee of their rights and responsibilities. Id. 825.300(c). This rights

and responsibilities notice must include, among other things, [a]ny requirements

for the employee to furnish certification of a serious health condition. Id.

825.300(c)(1)(ii). Additionally, it requires that [i]f leave has already begun, the

notice should be mailed to the employees address of record. Id. 825.300(c)(1).

Plaintiff argues that 825.300(c) applies to this case, and that because Plaintiffs

intermittent leave began on July 1, 2011, Defendants notice of its recertification

13

requirement should have been mailed to Plaintiffs address of record. However,

825.300(c) requires only that an employer provide this rights and responsibility

notice to an employee each time it provides an eligibility notice to the employee. Id.

825.300(c)(1). And an employer need only send an employee an eligibility notice

at the commencement of the first instance of leave for each FMLA-qualifying

reason . . . . Id. 825.300(b)(1).

Defendant argues that because 825.300(c) does not apply to recertification

requirements, and because 29 CFR 825.305 states that oral notification is

sufficient, an email was more than required under the regulations to provide

adequate notice. In support of this argument, Defendant cites Graham v. BlueCross

BlueShield of Tennessee, Inc., 521 Fed. Appx 419, 424 (6th Cir. 2013). Graham,

however, is distinguishable. First, in Graham, the defendants FMLA

administrator mailed the plaintiff two letters requesting recertification (although

the plaintiff denied receiving both letters) and the plaintiff admitted during her

deposition that her supervisors notified her orally on several occasions regarding

the need to submit additional medical certification. Id. at 421. Thus, there was no

question in Graham that the plaintiff was aware of the need to recertify her FMLA

leave.

In the present case, an important distinction must be made between oral

notification and email notification oral notification, a person-to-person

communication, guarantees actual notice to the employee. The transmitting of an

email, in the absence of any proof that the email had been opened and actually

14

received, can only amount to proof of constructive notice. This distinction becomes

particularly significant when an employee has expressed a preference for

correspondence to be sent by postal mail, as opposed to email. Here, there is this

genuine issue of material fact regarding whether Plaintiff made such a request.

Plaintiff claims that she never authorized FMLASource to communicate with her

via email only. Defendant claims Plaintiff authorized email only correspondence.

Since this matter is before the Court on Defendants motion for summary judgment,

the Court is bound to accept Plaintiffs version of events.

Furthermore, the Sixth Circuit has recognized that an employer who finds an

employees certification to be incomplete has a duty to inform the employee of the

deficiency and provide the employee a reasonable opportunity to cure it. See

Sorrell v. Rinker Materials Corp., 395 F.3d 332, 337 (6th Cir. 2005) (citing 29 C.F.R.

825.305(d)); Hoffman v. Professional Med Team, 394 F.3d 414, 418 (6th Cir. 2005)

(citing 29 C.F.R. 825.305(d)).

Plaintiff was working between October 7, 2011 and November 4, 2011, yet no

representative of Defendant made any effort to speak with Plaintiff about the need

to re-certify the basis of her FMLA leave request. Only after her several absences,

which Plaintiff thought were FMLA protected, had accumulated to the point that

termination was possible, did Defendant raise the issue with Plaintiff in person and

cause her to become aware of the need to re-certify. Furthermore, when Plaintiff

did submit the recertification paperwork from her doctor to FMLASource, her

FMLA leave was approved. However, this approval was not made retroactive, and

15

Defendant finalized Plaintiffs termination. This case presents a somewhat unique

set of facts, but under these circumstances there is clearly a genuine issue of

material fact as to whether Defendant provided Plaintiff a reasonable opportunity

to cure. This is particularly so, given that the Court must view in the light most

favorable to Plaintiff her claim that, from the very beginning, she never received

notice that she was required to re-certify. Considering the record as it currently

stands, there remain genuine issues of material fact in this case, and Defendants

motion for summary judgment as to Plaintiffs FMLA interference claim is therefore

denied.

III. CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, Defendants motion for summary judgment (Dkt.

23) is DENIED.

SO ORDERED.

s/Terrence G. Berg

TERRENCE G. BERG

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

Dated: October 15, 2014

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that this Order was electronically submitted on October 15,

2014, using the CM/ECF system, which will send notification to each party.

s/A. Chubb

Case Manager

You might also like

- EEOC Consent OrderDocument26 pagesEEOC Consent Ordereric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- ABA 2021 Midwinter FMLA Report of 2020 CasesDocument211 pagesABA 2021 Midwinter FMLA Report of 2020 Caseseric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Administrator's Interpretation On MisclassificationDocument15 pagesAdministrator's Interpretation On Misclassificationeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. The Pines of ClarkstonDocument15 pagesEEOC v. The Pines of Clarkstoneric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. New Breed LogisticsDocument24 pagesEEOC v. New Breed Logisticseric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Lowe v. Atlas Logistics Group Retail Services (Atlanta), LLCDocument2 pagesLowe v. Atlas Logistics Group Retail Services (Atlanta), LLCeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Atwood v. PCC Structurals, Inc.Document30 pagesAtwood v. PCC Structurals, Inc.eric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Valdes v. DoralDocument30 pagesValdes v. Doraleric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Cooper Tire & Rubber CompanyDocument24 pagesCooper Tire & Rubber Companyeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Mccourt v. Gatski Commercial Real Estate ServicesDocument6 pagesMccourt v. Gatski Commercial Real Estate Serviceseric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Lowe v. Atlas Logistics Group Retail Services (Atlanta), LLCDocument21 pagesLowe v. Atlas Logistics Group Retail Services (Atlanta), LLCeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Garcimonde-Fisher v. 203 MarketingDocument32 pagesGarcimonde-Fisher v. 203 Marketingeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Beauford v. ACTIONLINK, LLCDocument19 pagesBeauford v. ACTIONLINK, LLCeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. Ford Motor CompanyDocument46 pagesEEOC v. Ford Motor Companyeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Santiago V Broward CountyDocument8 pagesSantiago V Broward Countyeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. Dolgencorp, LLCDocument12 pagesEEOC v. Dolgencorp, LLCeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes, Inc.Document17 pagesEEOC v. R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes, Inc.eric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Perez Pier SixtyDocument29 pagesPerez Pier Sixtyeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. AllStateDocument19 pagesEEOC v. AllStateeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Valley Health System LLCDocument31 pagesValley Health System LLCeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Mathis v. Christian Heating & A/CDocument10 pagesMathis v. Christian Heating & A/Ceric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Osbon v. JetBlueDocument18 pagesOsbon v. JetBlueeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Smith V Hutchinson Plumbing Heating CoolingDocument25 pagesSmith V Hutchinson Plumbing Heating Coolingeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Bill No. 14102601, As AmendedDocument16 pagesBill No. 14102601, As Amendederic_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Berry v. The Great American Dream, Inc.Document11 pagesBerry v. The Great American Dream, Inc.eric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Hargrove v. Sleepy'sDocument40 pagesHargrove v. Sleepy'seric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Ruth v. Eka Chemicals, Inc.Document11 pagesRuth v. Eka Chemicals, Inc.eric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Graziosi v. City of GreenvilleDocument15 pagesGraziosi v. City of Greenvilleeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- EEOC v. Ruby TuesdayDocument7 pagesEEOC v. Ruby Tuesdayeric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- Jamal v. SaksDocument16 pagesJamal v. Sakseric_meyer8174No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Agreements: Applies With or Without Written MillingDocument10 pagesAgreements: Applies With or Without Written MillingAngelika GacisNo ratings yet

- The Gulf WarDocument3 pagesThe Gulf WarShiino FillionNo ratings yet

- Sec 73 of The Indian Contract ActDocument28 pagesSec 73 of The Indian Contract ActAditya MehrotraNo ratings yet

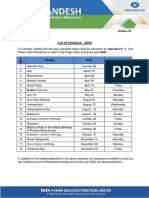

- Holiday List - 2020Document3 pagesHoliday List - 2020nitin369No ratings yet

- PCC v. CIRDocument2 pagesPCC v. CIRLDNo ratings yet

- Petition - Report & RecommendationDocument5 pagesPetition - Report & RecommendationAmanda RojasNo ratings yet

- G.R. Nos. 113255-56 People vs. Gonzales, 361 SCRA 350 (2001)Document6 pagesG.R. Nos. 113255-56 People vs. Gonzales, 361 SCRA 350 (2001)Shereen AlobinayNo ratings yet

- Easement Contract SampleDocument3 pagesEasement Contract SampleEkie GonzagaNo ratings yet

- RA 6766 - Providing An Organic Act For The Cordillera Autonomous RegionDocument44 pagesRA 6766 - Providing An Organic Act For The Cordillera Autonomous RegionRocky MarcianoNo ratings yet

- At First SightDocument1 pageAt First SightJezail Buyuccan MarianoNo ratings yet

- Thayer Strategic Implications of President Biden's Visit To VietnamDocument3 pagesThayer Strategic Implications of President Biden's Visit To VietnamCarlyle Alan Thayer100% (1)

- English - Sketches. Books.1.and.2Document169 pagesEnglish - Sketches. Books.1.and.2Loreto Aliaga83% (18)

- Protocol Guide For Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts January 2013Document101 pagesProtocol Guide For Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts January 2013Nok Latana Siharaj100% (1)

- Understanding AddictionDocument69 pagesUnderstanding AddictionLance100% (1)

- Administrative Due Process in University DismissalsDocument2 pagesAdministrative Due Process in University DismissalsLeyardNo ratings yet

- Effect of An Arbitration AgreementDocument28 pagesEffect of An Arbitration AgreementUpendra UpadhyayulaNo ratings yet

- Sanders vs. Veridiano Case DigestsDocument4 pagesSanders vs. Veridiano Case DigestsBrian Balio50% (2)

- Philippine municipal court interrogatories for unlawful detainer caseDocument3 pagesPhilippine municipal court interrogatories for unlawful detainer caseYannie MalazarteNo ratings yet

- 笔记整理Document189 pages笔记整理lin lin ZhangNo ratings yet

- Philippine Criminal Justice System ExplainedDocument40 pagesPhilippine Criminal Justice System ExplainedMary Jean Superable100% (1)

- Coffey v. United States, 117 U.S. 233 (1886)Document3 pagesCoffey v. United States, 117 U.S. 233 (1886)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- G C Am7 F Gsus G C F C: Chain BreakerDocument4 pagesG C Am7 F Gsus G C F C: Chain BreakerChristine Torrepenida RasimoNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Reflection of Movie Kramer Vs KramerDocument2 pagesAssignment - Reflection of Movie Kramer Vs Krameryannie11No ratings yet

- Waiver Declaration For Community OutreachDocument2 pagesWaiver Declaration For Community OutreachRahlf Joseph TanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - State and Society - All Politics Is Local, 1946-1964Document6 pagesChapter 7 - State and Society - All Politics Is Local, 1946-1964sjblora100% (2)

- Civil Procedure Code Exam Notes Final (13221)Document115 pagesCivil Procedure Code Exam Notes Final (13221)Rajkumar SinghalNo ratings yet

- Regular Administrator Special AdministratorDocument5 pagesRegular Administrator Special AdministratorApril Ann Sapinoso Bigay-PanghulanNo ratings yet

- Sapno An and Tolentino Rea CLED Activity 1Document2 pagesSapno An and Tolentino Rea CLED Activity 1Rea Camille D. TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Civil Code of The Philippines Article Nos. 1156-1171Document17 pagesCivil Code of The Philippines Article Nos. 1156-1171Kuma MineNo ratings yet

- Defense Statement of Tajalli Wa-Ru'yaDocument6 pagesDefense Statement of Tajalli Wa-Ru'yaStaceMitchellNo ratings yet