Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Full Face Coverings Prohibition in Public Places (Summary Offences) Bill 2014

Uploaded by

Stephanie AndersonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Full Face Coverings Prohibition in Public Places (Summary Offences) Bill 2014

Uploaded by

Stephanie AndersonCopyright:

Available Formats

Media Statement

28.10.14

Full Face Coverings Prohibition in Public Places (Summary

Offences) Bill 2014 - Lambie

Palmer United Senator for Tasmania Jacqui Lambie has submitted a draft bill and research

papers to the Office of Parliamentary Council in order to create Private Members legislation,

which will make it illegal for a person to wear a full face covering while in public in

Australia.

" The facial covering farce and stunt which occurred in Parliament house yesterday, was

caused by a leadership failure created by the PM and the Liberal/ National Parties. For basic

security reasons and the need for assimilation, identity-concealing garments should not be

allowed in Australian public or Parliament house. Once again, our enemies will laugh at us.

France, Belgium and Turkey (an Islamic country) have all sorted this problem out. So can

Australia. All it requires is some simple legislation, some courage and pride in the Australian

culture. said Senator Lambie.

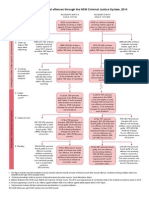

The private members legislation Ive asked the Parliamentary drafters to create (see attached

1), will be a simple Bill modelled on the recent French legal and political experience. (see

attached 2) Any person who is deemed by a police officer to have worn any identity

concealing garments in public unlawfully, will be issued with an on the spot fine or charged

with an offence which carries a maximum fine of $3,400. The process will be very simple

and similar to way traffic infringements are handled by police. said Senator Lambie

My private members bill will also introduce a further 2 offences. One for those who force or

intimidate an adult into wearing identity concealing garments and another for those who

force or intimidate children into wearing identity, concealing garments. said Senator

Lambie.

Any person found guilty of those offences will face maximum fine and/or jail term of

$34,000 and 6 months - with respect to the crime committed to adults. And a maximum fine

and/or jail term of $68,000 and 12 months if a person is found guilty of unlawfully forcing a

child to wear an identity-concealing garment in public. Religious excuses will not be

accepted as reasonable exemptions or lawful defence in my private members bill - because

the wearing of full-facial coverings is not mandated in any holy book.

However there will be exemptions for people to wear identity-concealing garments in private

places of worship - and of course in the sanctity of their own home. In addition the

prohibition of wearing face covering material or objects does not apply if such items are

authorised by law, are authorised to protect the anonymity of the person, are justified for

health reasons or on professional grounds, or are part of authorised artistic or traditional

festivities or events. said Senator Lambie

Attachment 1 Submission to Parliamentary Drafters

ATTACHMENT 2

Bill Name:

Full Face Coverings Prohibition in Public Places (Summary Offences) Bill 2014

Draft clauses of the Bill

Clause x - Commencement

This Act commences on the date of assent to this Act

Clause x - Wearing full-face coverings in public places

(1) A person must not, without reasonable excuse, wear a full face covering while in

a public place. Maximum penalty: 20 penalty units.

(2) A person who compels an adult to wear full face coverings in a public place, by any

means whatsoever, including by threat, inducements or any promise is guilty of an offence.

Maximum penalty: 6 months imprisonment and / or 200 penalty units

(3) A person who compels a child to wear full face coverings in a public place, by any means

whatsoever, including by threat, inducements or any promise is guilty of an offence.

Maximum penalty: 12 months imprisonment and / or 200 penalty units

(4) A full face covering is any article of clothing or other thing (such as a helmet) that

hides a persons face in a way that conceals the identity of the person.

(5) Without limitation, it is a reasonable excuse for the purposes of this section if

the wearing of the full face covering is reasonably necessary in all the

circumstances for any of the following purposes:

(a) the lawful pursuit of the persons occupation,

(b) participation in a lawful entertainment, recreation or sport,

(c) such other purposes as may be prescribed by the regulations.

(6) However, a religious or cultural belief does not constitute a reasonable excuse

for the wearing of a full face covering.

(7) For the purposes of this section, a full face covering can hide a persons face in a

way that conceals the identity of the person even though part of the persons

face can still be seen.

(8) The onus of proof of reasonable excuse in proceedings for an offence under

subsection (1) lies on the defendant.

(9) In this section: public place does not include a place of worship that authorised the

wearing of full face covering within the buildings ground.

(10) In this section:

Full face means the surface of the front of the head from the top of the forehead to the base

of the chin and the space in between, but not including the ears.

public place does not include a church.

threat means:

(a) a threat of physical force, or

(b) intimidatory or coercive conduct, or other threat, that does not involve a threat of a threat

of physical force.

Attachment 2 Parliamentary Library Research

2 October 2014

To From

Client: Senator Lambie Name: Diane Spooner and Catherine

Lorimer

Attention: Jo-Anna Barber Section: LBD

Tel: Tel: (02) 6277 2526

Email: Email: diane.spooner@aph.gov.au

TRIM

Reference:

10/1380

Banning the burka

Questions

Since the French ban of face covering in a public place in 2010 several other European

countries have also considered the issue.

1. Could you provide a background summary of the France experience in the lead up to their

introduction of the laws in their Parliament, the laws being passed and then the subsequent

decisions in the ECHR.

2. Could you provide a briefing for the Senator providing specific information about what

countries have introduced similar laws surrounding in regards to banning the covering of

your face in a Public Place similar to those which France introduced in 2010.

3. Any other background information on former instances where similar bans have previously

been contemplated in Australia.

4. Any laws which currently exists in this country banning the covering of your face in any

specific location / circumstances

5. Any other information relevant to this matter and the impacts of the bans on other countries

in the world.

FRANCE

The French Parliament gave consideration to the issue of banning face covering shortly after

the President Sarkozy raised the issue in June 2009.

The Bill was passed by the National Assembly by a vote of 335-2, and by the Senate by a

vote of 246-1 (with 100 abstentions.

France

Banned all religious symbols, including large crosses and head scarves from public

classrooms and buildings in 2004.

In May 2010 the French Cabinet approved a ban on veils that cover the face being worn

in public places. It also imposes fines and prison terms on those convicted of forcing a

woman to wear a burqa or niqab.

French lawmakers argue that the draft law is aimed at safeguarding the French

republics founding values of liberty, equality and fraternity, while others, such as a

member of the Community Party, add that it is necessary to combat extremism and protect

womens identity, femininity and gender equality. President Sarkozy said in a speech in

2009 that the problem with the burqa was not religious but concerned liberty and the

dignity of women. Catherine de Wenden, an expert on the history of immigration to

France, argues that the timing of the debate about the burqa is political: at the eve of the

[regional] elections, in the debate about national identity, the question of the burqa has

been put on the front scene in order to define national identity against what is different and

so against the burqa.

In an article on banning burqas, 2011, cites that opinion polls in Belgium and France suggest

that the initiatives had very wide community support, and noted that only a tiny number of

women wear the burqa or niqab: approximately 30 in Belgium and 1900 in France.

The French legislation, known as Act No 2010-1192 of 11 October 2010 prohibiting the

concealing of the face in public is generally worded in Article 1:

No one shall, in any public place, wear clothing designed to conceal the face.

The legislation also has Article 4 which creates an offence as follows:

Whosoever shall, by means of threats, duress or constraint, undue influence or misuse of

authority, compel another person, by reason of the sex of said person, to conceal their face

shall be liable to punishment of one years imprisonment and a fine of 30,000.

This provision is clearly aimed at fathers, husbands or religious leaders who force women to

wear face veils.

The prohibition of wearing face covering clothing does not apply if such clothing is

authorised by law, is authorised to protect the anonymity of the person, is justified for health

reasons or on professional grounds, or is part of sporting artistic or traditional festivities or

events. More on France is attached for information at the end of this memo.

ECHR

The case before the European Court of Human Rights on the French ban, S.A.S. v France

(application no. 43835/11) help that there had been no violation of Article 8 (right to respect

for private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights, and no violation of

Article (right to respect for freedom of thought, conscience and religion) unanimously, that

there had been no violation of Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the European

Convention combined with Articles 8 or 9.

The court accepted that the interference with the with the exercise of the applicants rights

under Articles 8 and 9 was a legitimate aim for the reasons of public safety and the

protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

The applicant was a French practising Muslim who wore the burqa and niqab in accordance

with her religious faith, culture and personal convictions.

Although the court appeared critical of the ban, overall it considered that it could be regarded

a proportionate to the aim, and therefor there was no violation of the Articles. The full press

release on the decision can be found in this link.

OTHER MATTERS: AUSTRALIAN CONTEXT SECTION 116 CONSTITUTION

AND DISCRIMATION LAWS

You may also be interested in the position in Australia and some of the constitutional

implications. The following section of this memorandum has been written by my colleague,

Mary Anne Neilson.

if federal legislation were to ban the wearing of a burqa would it be open to constitutional

challenge, and possible invalidation by the High Court under section 116 of the Constitution?

I think the attached article by Professor Anthony Gray, Section 116 of the Australian

Constitution and dress restrictions, considers this question very well. The paper considers

constitutional arguments that would arise if a government at either federal or state level

decided to ban dress often identified as having religious connotations. Amongst other things

the paper considers the meaning of the Hijab and Burqa; how bans or restrictions on religious

dress have been answered in other jurisdictions; and provides substantial background on how

the High Court has considered section 116. Gray notes that there have been few cases on

section 116 to assist with interpretation and as with its rights jurisprudence more generally,

the High Court has tended to read express provision in the Constitution conferring religious

freedoms conservatively. Despite the lack of cases Gray argues:

Considering the Australian precedents, a law prohibiting a person from appearing in public

whilst their face was covered would be difficult to justify on the grounds discussed in the

Jehovah's Witness case. It is difficult see how such a ban would be necessary to `preserve a

civil government'. When the matter is considered again, the High Court may adopt different

words in expressing a test for when laws which infringe religious freedom may nevertheless

be valid.

Despite this, on the current state of the High Court jurisprudence on section 116, a law with

the effect of banning religious dress such as a burqa would probably not be unconstitutional.

This is because it would not meet the current test for invalidity set out in Kruger and Black ie

that only a law with the express purpose of infringing the rights mentioned in section 116 is

invalidated by that section. The federal government could state that its purpose in enacting

the law was to promote civil harmony or assimilation, or to promote public safety by making

it easier to identify everyone, and according to the High Court, this would be a decisive factor

in declaring the law to be valid. The court might draw on the European and American

precedents in support of this position, to find that the law was justified in terms of preserving

equality and liberty among citizens, and avoiding supposed subjugation of women. However,

as has been indicated, the research is difficult to reconcile with a bald assertion that the

wearing of religious dress such as the burqa is necessarily a sign of subjugation of women or

gender or religious inequality.

I would prefer the High Court took a broader view to the question of the rights protected by

section 116 of the Constitution than previous cases have provided. The test in Kruger for

invalidity pursuant to the section, that the law be passed with the purpose of restricting

religious freedom, is with respect too narrow. As interpreted by the High Court, this section

has very little operation, in that the Commonwealth, by carefully drafting its legislation, can

ensure that its law avoids invalidity under section 116, even when the law clearly has the

effect of restricting the rights implied in section 116. There is hope for a broader view, with

some of the judgments in Black allowing that a law which had the effect or result of

interfering with religion may be offensive to section 116, even if that were not its purpose.

This is of course not the only context in which the High Court has read `rights' contained in

the Constitution narrowly, so that they have little if any scope and can be subverted by

intelligent drafting. Rights provisions must not be read pedantically or narrowly, or in such a

way as to make them easy for the drafter to subvert. Nor should the courts blindly accept

claims by parliament that limits on religious freedoms are justified on `equality',

`assimilation', `esprit de corps' or `women's rights' grounds as has occurred elsewhere,

without a thorough investigation of the evidence.

I recommend Grays complete paper to you.

You may also be interested in a paper by Anne Hewitt and Cornellia Koch, Can and Should

Burqas be Banned. Hewitt and Koch conclude that there is no legal limitation on the

Commonwealths power to implement legislation banning the wearing of the burqa and niqab

and it is unlikely that there is any real limitation on the enactment of an effective state or

territory ban. Their view is that the most likely impediment to state legislation is that it might

constitute indirect racial discrimination in contravention of the Racial Discrimination Act

1975 (Cth) but this could only be established where the majority of people affected by any

ban were of one racial or ethnic group.

This view has been reiterated by the NSW Bar Association:

OTHER LAWS

New South Wales has passed the Identification Legislation Amendment Act 2011 was passed

on 15 September 2011, becoming the first legislation in Australia to specifically deal with

full face coverings. [CHECK]. Basically this Act amended the Law Enforcement (Powers and

Responsibilities) Act 2002 to insert the following definition:

Insert in alphabetical order in section 3 (1):

face means a persons face:

(a) from the top of the forehead to the bottom of the chin, and

(b) between (but not including) the ears.

face covering means an item of clothing, helmet, mask or any other thing that is worn by a

person and prevents the persons face from being seen (whether wholly or partly).

Further analysis of the Australian perspective can be found in footnote 8 of this

memorandum, in an article by Renae Barker.

OTHER ATTEMPTS

In June 2010, the New South Wales Member of Parliament and President of the Christian

Democratic Party, Reverend Fred Nile, introduced the Summary Offences Amendment (Full-

face Coverings Prohibition) Bill 2010 (NSW) in the New South Wales Legislative Council.

The bill sought to amend the Summary Offences Act 1988 (NSW) by inserting two new

offences in Part 2 of the Act. The first would have made it an offence to wear a face covering

while in a public place and the second would have made it an offence to compel another

person to wear a face covering in a public place. An exception to the general prohibition was

given where the person who had covered their face had a 'reasonable excuse'. The onus of

proving the existence of a reasonable excuse was placed on the defendant. The Bill did not

mention the niqab or burqa specifically, but did state that 'a religious or cultural belief does

not constitute a reasonable excuse for the wearing of a face covering'. The Bill lapsed.

In an article by Renae Barker (see footnote 8 below), and Independent in the South Australian

parliament also presented a Bill. Barker states:

In July 2010, one month after Fred Nile introduced his Bill, Independent South Australian

MP, Robert Such, introduced the Facial Identification Bill 2010 (SA). This bill was a more

nuanced approach to the issue. It did not create a blanket ban on full face coverings in public.

Instead it gave prescribed premises the power to display a sign which indicated that a person

whose face was obscured could not enter the premises. Prescribed premises were defined in

the bill as premises used for an authorised deposit institution (ADI), a State or Federal

government agency or 'any other business or activity where, for reasons of security or for the

purposes of compliance with any Act or law, it is necessary or desirable to establish the

identity of persons in the premises so used'.

This Bill was also unsuccessful.

Most laws in state and territory jurisdictions will be concerned with policy issues such as

public safety, verification of identity and other legitimate purposes. Further work can be done

on this if required.

ATTACHMENT: EXTRACT FROM ARTICLE BY JACLYN GIFFEN

The veil of the ban: a legal, social and political discourse.

3.2. 2004 FRENCH HEADSCARF LAW

The concept of laicite was invoked in 2004 when the French State banned any form of

religious symbol or manifestation thereof - including Islamic headscarves - from

primary and secondary state schools 8 French lawmakers believed that this ban

would encourage integration into the country "and help the country understand itself

in light of increasing religious and ethnic diversification." Following the law's entry

into force, there was a severe public reaction, including riots and daily violence which

demonstrated the tension and social repercussions of the law. The European Court of

Human Rights in several cases that followed the law's implementation, however,

upheld the law stating that the limitation on the freedom of religion and its

manifestations were justifiable according to the doctrine of proportionality In their

decision, the Court granted a wide margin of appreciation to France since the principle

of secularism was a founding principle of the state.

"'The Court also notes that in France, as in Turkey or Switzerland, secularism is a

constitutional principle, and a founding principle of the Republic, to which the

entire population adheres and the protection of which appears to be of prime

importance, in particular in schools. The Court reiterates that an attitude which

fails to respect that principle will not necessarily be accepted as being covered by

the freedom to manifest one's religion and will not enjoy the protection of Article 9

of the Convention (see Refah Partisi (Prosperity Party) and Others, cited above,

93). Having regard to the margin of appreciation which must be left to the member

States with regard to the establishment of the delicate relations between the

Churches and the State, religious freedom thus recognised and restricted by the

requirements of secularism appears legitimate in the light of the values

underpinning the Convention."

This principle of secularism that removes religion from the public sphere is clearly

seen by the Court in this case to be part of the French national identity, representing

the core values of neutrality, equality and freedom.

However, for those who do not subscribe to the French national identity, the

protection of laicite may not be seen to legitimately justify the infringement on

religious expression. Upon accepting his party's nomination for President of France,

Nicolas Sarkozy said that it is "unacceptabie to want to live in France without

respecting and loving France and learning the French language... If you live in France

then you respect the laws and the values of the Republic" - the same Republic he also

referred to as "the heirs of 2000 years of Christianity."

3.3. 2011 PUBLIC SPACE BANNING OF CONCEALED FACES

In 2009, the public debate surrounding the issue of face covering in public spaces

arose in France, specifically targeting the wearing of burqas and niqabs by French-

Muslim women. French President Nicolas Sarkozy, when addressing parliament,

expressed his strong dislike for the Islamic veil, calling it not a sign of religion but

rather a sign of subservience. He stated that "[the veil] will not be welcome on French

soil. We cannot accept in our country, women imprisoned behind a mesh, cut off from

society, deprived of all identity. This is not the French republic's idea of women's

dignity."2 France is home to Western Europe's largest population of Muslims; about

five million in total. However, it is estimated that only 2,000 women in France wear

the burqa.

The most recent French Law, Act prohibiting concealment of the face in public

Space was passed by the Senate of France on 14 September 2010. This law is a further

extension of the previous laws, and bans the wearing of any face-covering, including

masks, helmets, balaclavas, and the Muslim burqa and niqab, in any public space

whatsoever, including in the course of employment within the public sector. Examples

of 'public spaces' include anything such as the street, museums, shops, public

transportation, parks, banks, etc. After a decision in October 2010 by France's highest

court which stated that the French law to ban full-facial veils in public was in accordance

with the constitution, except in the case of places of worship, the law came into full

force in April 2011. Those who violate the law have to pay a fine of up to E 150, and/or

participate in citizenship education. Those persons who force another to wear any face

coverings can also be penalized with a fine of C 30,000 and one year in prison;

can be doubled if the victim is under the age of majority, or 18 years of age. The police

are not empowered to forcibly remove the veil. Although, there have been continued

incidents of assault by citizens against these women who are in non-compliance with

the law, demonstrating the dangers associated with targeting an already vulnerable

minority population and gender of the population; namely, women.

. Z Malik, Frances burka dilemma, BBC News, 16 March 2010, viewed 8 July 2010,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_8568000/8568024.stm

. Ibid.

. A Gray, Section 116 of the Australian Constitution and dress restrictions, Deakin Law

Review, v. 16 no. 2, 2011, viewed 25 May 2012,

http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/jrnart/1357639/upload_binary/1357

639.pdf;fileType=application/pdf#search=%22gray%20burqa%22

. Ibid, pp. 316-317.

. A Hewitt and C Koch, Can and Should Burqas be Banned, Alternative Law Journal, v.

36, 2011, viewed 25 May 2012,

http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/jrnart/740401/upload_binary/7404

01.pdf;fileType=application/pdf#search=%22Anne%20Hewitt%20%20Burqas%22

. Ibid, p. 20.

. New South Wales Bar Association, Media Statement, Clothing, Religious Beliefs and

Racial Vilification, 3 October 2014.

. Renae Barker, The Full Face covering Debate: An Australian Perspective.(no citation

available).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- PNG Supreme Court Decision On Manus IslandDocument34 pagesPNG Supreme Court Decision On Manus IslandStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Select Committee On The Recent Allegations Relating To Conditions and Circumstances at The Regional Processing Centre in NauruDocument219 pagesSelect Committee On The Recent Allegations Relating To Conditions and Circumstances at The Regional Processing Centre in NauruStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Shorten's Opening Address To ALP ConferenceDocument13 pagesShorten's Opening Address To ALP ConferenceStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Australian Citizenship Amdt (Allegiance To Australia) Bill 2015-A4Document14 pagesAustralian Citizenship Amdt (Allegiance To Australia) Bill 2015-A4Adam ToddNo ratings yet

- Sexual Attribution DiagramsDocument9 pagesSexual Attribution DiagramsStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Ricky Muir On Marriage EqualityDocument2 pagesRicky Muir On Marriage EqualityStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Penny Wong On Marriage EqualityDocument5 pagesPenny Wong On Marriage EqualityStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Reasons For Ruling On Disqualification Application Dated 31 August 2015Document67 pagesReasons For Ruling On Disqualification Application Dated 31 August 2015David Marin-GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Abbott's Address To Federal Women's Committee Luncheon AdelaideDocument5 pagesAbbott's Address To Federal Women's Committee Luncheon AdelaideStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Storyboard AfghanistanDocument18 pagesStoryboard AfghanistanOuest-France.frNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Competitiveness White PaperDocument152 pagesAgricultural Competitiveness White PaperStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Superannuation Policy For Post-RetirementDocument110 pagesSuperannuation Policy For Post-RetirementStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Speech On Marriage Amendment (Marriage Equality) Bill 2015Document6 pagesSpeech On Marriage Amendment (Marriage Equality) Bill 2015Stephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Terror Suspects To Lose CitizenshipDocument2 pagesTerror Suspects To Lose CitizenshipStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Interim Analysis of The 2015 16 Federal BudgetDocument13 pagesInterim Analysis of The 2015 16 Federal BudgetStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Shorten To Move Private Member's Bill On Marriage EqualityDocument1 pageShorten To Move Private Member's Bill On Marriage EqualitySBS_NewsNo ratings yet

- Chris Bowen - NPC SpeechDocument13 pagesChris Bowen - NPC SpeechPolitical AlertNo ratings yet

- Report On Foreign Investment in Residential Real EstateDocument148 pagesReport On Foreign Investment in Residential Real EstateStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Bill Shorten's 2015 Budget ReplyDocument21 pagesBill Shorten's 2015 Budget ReplyStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Assets Test Parameters - Non Homeowners Pension ImpactDocument2 pagesAssets Test Parameters - Non Homeowners Pension ImpactStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Antisemitism Worldwide 2014Document94 pagesAntisemitism Worldwide 2014Stephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Assets Test - Homeowner Pension ImpactDocument2 pagesAssets Test - Homeowner Pension ImpactStephanie Anderson100% (1)

- Address To Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry LuncheonDocument7 pagesAddress To Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry LuncheonStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- ANU Polling On Australian AttitudesDocument24 pagesANU Polling On Australian AttitudesStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- GST ReviewDocument146 pagesGST ReviewStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Issues ANU Poll 2015Document16 pagesIndigenous Issues ANU Poll 2015Stephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet - Labors Plan For Fair Sustainable SuperDocument5 pagesFact Sheet - Labors Plan For Fair Sustainable SuperPolitical AlertNo ratings yet

- Review of Mental Health Programmes and ServicesDocument25 pagesReview of Mental Health Programmes and ServicesStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Tax Final Discussion PaperDocument202 pagesTax Final Discussion PaperStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- Tax Final Discussion PaperDocument202 pagesTax Final Discussion PaperStephanie AndersonNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- WorkSafeBC Fraser Regional Correction Centre 2012Document43 pagesWorkSafeBC Fraser Regional Correction Centre 2012Bob MackinNo ratings yet

- University of The Philippines College of Law: Cebu Oxygen v. BercillesDocument2 pagesUniversity of The Philippines College of Law: Cebu Oxygen v. BercillesJuno GeronimoNo ratings yet

- GR 198146 DigestDocument3 pagesGR 198146 Digestceilo coboNo ratings yet

- A.M. No. 08-11-7-SCDocument18 pagesA.M. No. 08-11-7-SCStenaArapocNo ratings yet

- Labor Law FundamentalsDocument165 pagesLabor Law FundamentalsPJ HongNo ratings yet

- Cases PersonsDocument115 pagesCases PersonsChano MontyNo ratings yet

- Content of Procedural Obligations (Unbiased Decision-Maker) - NCA Exam ReviewerDocument22 pagesContent of Procedural Obligations (Unbiased Decision-Maker) - NCA Exam ReviewerrazavimhasanNo ratings yet

- Fiitjee Aiits Class 11 - SyllabusDocument4 pagesFiitjee Aiits Class 11 - SyllabusShaurya SinhaNo ratings yet

- Regional Trial Court Branch 27 Evidence OfferDocument3 pagesRegional Trial Court Branch 27 Evidence OfferMatthew Witt100% (2)

- Tcs Employment Application FormDocument5 pagesTcs Employment Application FormAjithNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Law and Social Legislation PrimerDocument35 pagesAgrarian Law and Social Legislation PrimerMoonNo ratings yet

- Legal Writing Principles ExplainedDocument8 pagesLegal Writing Principles ExplainedSayan SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Indian Contract Act assignment novationDocument2 pagesIndian Contract Act assignment novationZaman Ali100% (1)

- As 2001.4.21-2006 Method of Test For Textiles Colourfastness Tests - Determination of Colourfastness To LightDocument2 pagesAs 2001.4.21-2006 Method of Test For Textiles Colourfastness Tests - Determination of Colourfastness To LightSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- (A.C. No. 10911. June 6, 2017.) Virgilio J. Mapalad, Sr. vs. Atty. Anselmo S. Echanez PrincipleDocument2 pages(A.C. No. 10911. June 6, 2017.) Virgilio J. Mapalad, Sr. vs. Atty. Anselmo S. Echanez Principlechrystel0% (1)

- An Overview of Land Titles and DeedsDocument5 pagesAn Overview of Land Titles and DeedsowenNo ratings yet

- 9 TortDocument6 pages9 TortrahulNo ratings yet

- LTA LOGISTICS Vs Enrique Varona (Varona Request of Production For Discovery)Document4 pagesLTA LOGISTICS Vs Enrique Varona (Varona Request of Production For Discovery)Enrique VaronaNo ratings yet

- Constitution and By-Laws of The Teachers and Employees Association of Batac National High School Batac CityDocument6 pagesConstitution and By-Laws of The Teachers and Employees Association of Batac National High School Batac CityJoe Jayson CaletenaNo ratings yet

- Layton Clevenger PCDocument4 pagesLayton Clevenger PCbradbeloteNo ratings yet

- Smart v. SolidumDocument2 pagesSmart v. SolidumAlexis Elaine BeaNo ratings yet

- Rules of Practice in Patent CasesDocument171 pagesRules of Practice in Patent CasesHarry Gwynn Omar FernanNo ratings yet

- Pardo v. Hercules LumberDocument1 pagePardo v. Hercules LumbertemporiariNo ratings yet

- Philippines vs. Lugod rape confession inadmissibleDocument1 pagePhilippines vs. Lugod rape confession inadmissibleRica100% (1)

- #5 Career Executive Service Board Vs Civil Service CommissionDocument2 pages#5 Career Executive Service Board Vs Civil Service CommissionMark Evan GarciaNo ratings yet

- Agenda Item: Backgrou NDDocument18 pagesAgenda Item: Backgrou NDMichael JamesNo ratings yet

- Housing Authority of The City of Pasco and Franklin County (Hacpfc) General Program InformationDocument3 pagesHousing Authority of The City of Pasco and Franklin County (Hacpfc) General Program InformationAshlee ReneeNo ratings yet

- University of Professional Studies, Accra (Upsa) : 1. Activity 1.1 2. Activity 1.2 3. Brief The Following CasesDocument8 pagesUniversity of Professional Studies, Accra (Upsa) : 1. Activity 1.1 2. Activity 1.2 3. Brief The Following CasesADJEI MENSAH TOM DOCKERY100% (1)

- Getty Images - Rights License AgreementDocument9 pagesGetty Images - Rights License AgreementDorie ENo ratings yet

- Commissions of Inquiry Act, 1952Document18 pagesCommissions of Inquiry Act, 1952rkaran22No ratings yet