Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Mothman A Folkloric Perspective

Uploaded by

rsharom32467050 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

223 views11 pagesfolklore

Original Title

The Mothman a Folkloric Perspective

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentfolklore

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

223 views11 pagesThe Mothman A Folkloric Perspective

Uploaded by

rsharom3246705folklore

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

1

The Mothman: A Folkloric Perspective

Corey J. Chimko

The events of November 1966 through December 1967 in Point Pleasant, WV are well

known in Fortean circles. Since that time, the progenitor of that series of events, the so-

called Mothman, has grown into nothing less than an American folkloric icon.

Regardless of what actually happened in Point

Pleasant over forty years ago (and this article will not

seek to review those events),

1

the episode has since

grown into what might be called a folklore motif, cultural

meme or Fortean geography,

2

with many attendant

characteristics that were both reported at the time of the

events, as well as some that were either inferred or, some

would say, invented, by later investigators and

proponents of the case. Barring associated phenomena

such as UFOs and Men in Black, the characteristic

aspects of the Mothman mythos as it stands today include

1) the creatures large, glowing red eyes, described by

witness Linda Scarberry as two big eyes like automobile

reflectors

3

; 2) the creatures eerie cry or squeak,

described by witnesses Mary Malette and Virginia

Thomas as like a big mouse

4

and like a bad fan belt

5

,

respectively; 3) the creatures ability to fly, using the big

wings folded against its back,

6

and 4) the creatures role as a harbinger of disaster,

appearing on location days, weeks or months preceding a major calamity, in this case the

collapse of the Silver Bridge.

7

The story of the Mothman and the events surrounding its appearance have

continued to be popularized and studied (with varying degrees of adherence to scholarly

rigor) by authors such as John Keel in The Mothman Prophecies, Gray Barker in The

Silver Bridge, Loren Coleman in Mothman and Other Curious Encounters, and skeptic

Joe Nickell in The Mystery Chronicles.

8

The 2002 film based on Keels book injected a

number of other apparent sightings into the Mothman mythos, including appearances

prior to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the hurricane in Galveston, TX. Coleman,

who consulted on the film, insists however that there are no records of Mothman at

Chernobyl or Galveston or before any earthquakes, that Mothman encounters did not

happen in those locations, and that these factoids were nothing more than little tidbits

to support the storyline.

9

Nevertheless, to his chagrin and that of those in search of the

truth, these stories continue to be recounted as fact on the now innumerable websites,

blogs, and self-published (i.e. non-peer-reviewed) books dedicated to fortean topics.

Indeed, one could argue that the internet has become the most powerful engine for the

transmission of folklore ever invented.

But were the events of 1966-7 the genesis of the Mothman mythos? Can the

elements of this story be traced back further than the 1960s, earlier perhaps than even the

twentieth century? Keel asserts that winged beings are an essential part of the folklore of

every culture,

10

recounting a number of flying humanoid stories dating from the late

Fig. 1. A contemporary drawing of the Mothman.

2

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in America, including the 1877-80 Flying Man

of Coney Island sightings and the 1908 Letayuschiy chelovek [flying human being]

Gobilli River sighting.

11

Coleman adds the bizarre American flying machine-man

sightings in Louisville, KY (1880), Mount Vernon, IL (1897), Lincoln, NE (1922),

Chehalis and Longview, WA (1948), Houston, TX (1953) and Arlington, VA (1968-9),

as well as the international sightings in Cubeco, Portugal (1915), Kent, England (1963),

and Vietnam (1969).

12

As intriguing as these sightings are, the only thing they seem to

have in common with the West Virginia Mothman is that they are winged, flying,

humanoid-shaped beings, but they lack the other elements of the mythos.

13

Indeed, it precisely because it is so strange in terms of its content, duration, and

the fact that it seems to have incorporated a great many fortean stalwarts into the same

event, that the episode is one of the weirder and more memorable in fortean lore. It would

stand to reason, therefore, that it would be that much more difficult to find historical

precedents. But the paths of folklore and fortean research meet at strange intersections

A Bizarre Synchronicity

As a student of cryptozoology and Fortean

studies, I am drawn to the art and folklore

surrounding the myriad creatures reported by

the cultures of the world in all times and

places. I was recently perusing a volume of

the works of Henry Fuseli, (b. Johann

Heinrich Fssli - February 7, 1741 April 17,

1825), a Swiss-born British painter famous for

his depictions of the supernatural.

14

Among

his most famous works are his paintings

depicting fairy scenes from Shakespeares A

Midsummer Nights Dream. In the bottom

left-hand corner of one of these paintings,

titled Titania, Bottom and the Fairies,

15

a

most bizarre and to some, perhaps,

familiar, figure alights (Figs. 2 and 3).

According to Fuseli researcher

Frederick Antal, the small grotesque

figure dancing in the lower left corner

shows one of Callots dancers as a winged

insect. This strange figure in the

Midsummer Nights Dream excited so

great a fascination that Fuselis 19

th

Fig. 2. Henry Fuseli. Titania, Bottom and the Fairies (1793-4). Oil on

Canvas. 169 x 135cm. Kunsthaus Zrich, Vereinigung Zrcher

Kunstfreunde.

Fig. 3. Insect figure detail from Henry Fuseli. Titania, Bottom and the Fairies

(1793-4). Oil on Canvas. 169 x 135cm. Kunsthaus Zrich, Vereinigung Zrcher

Kunstfreunde.

3

century imitator, von Holst, later made a

separate etching of it (see Fig. 4), and

Goethe used this figure in the second part

of Faust in the presentation of Oberon and

Titanias Golden Wedding.

16

Although it may very well be that Fuseli

was inspired by Callot, it also must be said

that the figure is undoubtedly based on a

moth. The shape of the wings, as well as

the size and shape of the antennae make

this clear. Intriguingly, Fuseli has also

chosen to imbue the figure with large,

glowing red eyes. It is, in every sense, a

depiction of a Moth-Man. The subject

matter and appearance of the figure takes

on a greater significance with some

knowledge about Fuselis background and

his non-artistic pursuits.

Fuseli and the Moths

It turns out that Henry Fuseli was an avid and serious entomologist. A contemporary

wrote of Fuseli that he was unrivalled as an entomologist; and so indefatigable, that he

would rise at four oclock and walk several miles to watch the operations of spiders on a

hedge.

17

He was employed as a reviewer of entomological books,

18

and was intimately

involved in the production and procurement of a number of illustrated insect volumes;

19

writing on his personal procurement of some insect drawings, he states to an

acquaintance that those I wished most for, are the Papilio and the Moth.

20

Indeed, a

published volume of his correspondence

21

makes it clear that Fuseli was particularly

interested in moths, and collected a great many of them:

You will transmit to [a friend of John Knowles] my thanks and condolences on the

escape of his Atropos, though I cannot blame the Sphinx for seizing that opportunity for

French leave mine, apparently still in health, continues in the pupa. As Mr. R[ackett]

mentions the S. Stellatarum, I wish, that in his researches he would pay particular

attention to Gallium and Rubia, as the means of making us better acquainted with Sphinx

Galii and Lineata Linn.

22

The Atropos that Fuseli refers to is Sphinx atropos or Acherontia atropos

23

[Fig. 5].

Commonly known as the deaths head hawk moth for the marking on its thorax which

can variously look like a skull, skull and crossbones, or a deaths head, this moth is so

large that it is commonly mistaken for a hummingbird.

24

When irritated or palpated, it is

still more striking and unique from the fact of possessing a voice, or the power of uttering

a kind of shrill, plaintive, and mournful squeak, somewhat resembling that of a mouse.

25

Its range extends from northern Africa as far north as Russia, and it is commonly seen as

a migrant in many parts of Europe.

26

As one might expect, such a remarkable species has

Fig. 4. Etching by Theodor Mathias von Holst (1810-44) after Fuseli, 19

th

century.

4

not only been noticed, but over the centuries has acquired a significant amount of

folkloric significance.

The Folklore of the Deaths Head Hawk Moth

The time of year that the adult moth

emerges is late autumn, right around the

end of October, a time long associated

with the appearance of spirits.

27

Regarding

its species name, Acherontia atropos:

Acheron was the underworld river of pain

in Greek mythology, and according to

Vergil, the principal river of Tartarus,

from which the Styx and Cocytus both

sprang.

28

It was one of the rivers that

Charon, the ferryman of the underworld,

would ferry souls across.

29

Atropos, the eldest of the three fates, is she who chooses the

manner of each persons death, cutting their life thread; she who

Comes the blind Fury with th'abhorred shears,

And slits the thin spun life."

30

In Eastern Europe, the moths crepuscular habits and their penchant for entering

houses in such numbers that the wind from their wings was enough to blow out candles,

resulted in them being regarded with horror as an evil omen, a forerunner of war,

pestilence, famine, and death to man and beast.

31

In Poland, where it is called the

Deaths Head Phantom and Wandering Deaths Bird,

32

its high-pitched shriek was

thought to originate from a screaming, death-stricken child, and to the Creoles the dust

of its wings was said to be capable of causing blindness if it came in contact with the

eye.

33

In England, it was sometimes considered a familiar of witches, and whispers in

their ear the name of the person for whom the tomb is about to open.

34

As far back as

the fourteenth century in Italy and France, the moth was seen as a carrier of pestilence

and an omen of impending death, likely due to its appearance in Brittany during the

plague.

35

Even the larva of the deaths head hawk moth is surrounded with sinister

superstitions. Archaeologists have unearthed medical amulets or charms in the shape of

the larva of the deaths head hawk moth in Ireland (Fig. 6), where the practice among

the peasantry, when they find one of these latter grubs, is to insert it in the cleft of a

young ash sapling, which soon puts an end to

the caterpillar, whatever effect it may have on

the murrain-epidemic. Even to dream, you see

this caterpillar betokens ill-luck and

misfortune.

36

The charms were worn as

apotropaic curative agents according to the

idea of similia similibus curantur, or like

cures like, the basic tenet of homeopathic or

Fig. 5. Acherontia atropos, the Deaths Head Hawk Moth.

Fig. 6. Connoch, or Murrain Caterpillar Charm, found near Doneraile,

County Cork. (Wood-Martin: 77, Fig. 26)

5

sympathetic magic.

37

In Wiltshire, it was believed that

bringing the caterpillar of the moth into the house would

result in an imminent death.

38

The sinister associations harbored by this species

continue in mainstream culture today; in the 1991 film The

Silence of the Lambs, the pupa was left in the mouth of the

killers victims, and a full-grown adult was featured on

promotional material (Fig. 7).

Badenloch sums up the folkloric legacy of the moth

in eloquent fashion:

To [the] fertile imagination[], the grim features stamped

thereon represent the head of a perfect skeleton, its cry becomes

the moan of anguish, or grief, or of a child; the very brilliancy of

its eyes typifies the fiery element whence it came, for they

implicitly believe it to be a messenger of evil spirits.

39

* * *

It would seem that Fuseli was intimately acquainted not only with the scientific aspects of

A. atropos, but also with its folkloric aspects. Though he probably had a first-hand

familiarity with local superstition, it was also during his time that the first large

collections of local folklore and fairy legends began to be published in England.

40

Indeed,

moths appear in many of his works,

41

and Fuseli seems to have delighted in taking

advantage of the more mysterious and metamorphic qualities of this insect; according to

Lentzch, et.al., Fuseli uses figures from popular folklore as often as he uses literary

characters [] all his creatures have in common an adaptation of their folk original to

contemporary taste.

42

Antal also suggests that he may have been influenced by the works of Jacopo

Ligozzi (1547-1627), an Italian painter, designer, illustrator and miniaturist in whose

works a scientific interest in animals, botany and a love of the fantastic mixed.

43

Schiff,

et.al. echo their sentiments, asserting that Fuseli was one of the first artists to recognize

the enormous visual potential of English folk superstition, and that in post-

enlightenment Britain it became fashionable to acknowledge the existence of even the

most abstruse manifestations of the supernatural.

44

[Sounds like post-Roswell America!]

This milieu seems to have produced the first fine-art depiction of a bona-fide Moth-

man.

It was during Fuselis time, of course, that America gained independence from

Britain, and colonization was in full swing. It is not difficult to imagine those colonists

bringing their folklore, their books, and even their insects, with them.

Conclusions

And so it would seem that we have, in the works of Fuseli and the attendant

folklore on which they were based, an encapsulation and expression of the more or less

complete Mothman mythos, almost three hundred years before the events in Point

Fig. 7. Promotional poster for The Silence of

the Lambs, 1991, showing the A. atropos.

6

Pleasant.

45

The folklore which inspired him is more ancient still, and may not even have

been confined to the European continent.

People often take the existence of folklore for granted, as if it somehow trickles

down to us through the ether of time of its own accord. Of course, folklore, like anything

else, must be transmitted in some form by people, be it orally, in print, or in this case, in

art. Coleman has written on the evolution of the depiction of the Mothman in popular

culture, saying that

Mothmen didnt have hands with four fingers, toes with claws, well-defined rib-cages,

or leathery wings. Most of those details were not even seen or were described differently.

The diffuse imagery of Mothman has drifted into something with a head, arms, and

limbs, although few described it that way in the 1960s. [] The insect notion, the bat

man appearance, and the creey [sic] demon look are fantastic imagined images for

Mothman.

46

This of course is true, if you accept that the incidents in Point Pleasant constitute the

launching point for this particular fortean geography, but, as we have seen, they do not.

If we incorporate the depictions of Fuseli and the Pueblo

Indians into the history of Mothman art, there were indeed

Mothmen of varying physical appearances before the Point

Pleasant creature came on the scene.

Though I am certainly not arguing that the

witnesses of the 1966-7 events were hallucinating or that

they did not have real experiences, I am arguing that those

experiences do, in typical uncanny fortean fashion, seem to

fit into a larger body of experiences, folk beliefs, and

symbology that can be shown to go back at least as far as

the fourteenth century, and likely further back still.

And while we are on the subject of uncanny fortean

synchronicities, it might do well to comment on that of our

celebrity creatures name. Apparently the name

Mothman was a reporters takeoff on the then-current

Batman TV series.

47

But why then was he not called the

Bat-man or the Bird-man (which would have been

more in keeping with contemporary descriptions)? Instead

it was the appellation Mothman that stuck, and it goes without saying that if it had not, no

study such as the current one would have taken place, and the parallels between the

Mothman mythos and the folklore of the deaths head hawk moth would have remained

obscure.

Some researchers have argued that men like John Keel, Jim Moseley and Gray

Barker were responsible for the insertion of many aspects of the modern Mothman

mythos, including its association with the collapse of the Silver Bridge, and other, more

personal crises;

48

what Dixon calls the final narrative twist in Keels Gnostic tale of

impending doom.

49

Could it be that these men were aware of the folklore surrounding

moths and constructed certain aspects of the mythos along those lines? Perhaps. Perhaps

not. Perhaps subconsciously and/or unintentionally. If we accept the mythos is part of

some fundamental symbolic reality in which we all live, if the Mothman is of singular

Fig. 12. Robert Roachs Mothman statue in Point

Pleasant, WV.

7

interest not because of his anomalous character, but because his incorporation into

systematized bodies of knowledge has become emblematic of how people proceed to live

and cope with the notion of uncertainty,

50

then perhaps their involvement was not

wholly self-directed.

In the end, from the folkloric perspective, it doesnt really matter. I have always

argued that in terms of fortean mysteries, those that are solved will enter the realm of

science, while those that are not will enter the realm of folklore. Regardless of their

motives, men like Keel, Barker, Moseley, Fuseli and even the ancient Pueblo Indians are

both the inheritors and the agents of folkloric transmission. They received and perhaps

built upon that folklore, and their ideas are now all part of the Mothman mythos as it

moves forward. A mythos that, if we judge by its increasing appearance in popular

culture, shows no signs of abating.

Fig. 13. Post-1967 depictions of the Mothman in popular culture.

8

Works Cited:

Antal, Frederick. 1956. Fuseli Studies. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Badenloch, L.N. 1899. True Tales of the Insects. London: Chapman & Hull.

Child, A.B. & Child, I.L. 1993. Religion and Magic in the Life of Traditional Peoples. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Coleman, Loren. 2002. Mothman and Other Curious Encounters. New York: Paraview Press.

_____. 2007. Mothmans Fate, Cryptomundo. Posted 2007-09-08; retrieved 2010-07-14.

http://www.cryptomundo.com/cryptozoo-news/mothman-fate/.

David, Gary. 2008. The Mothman Pottery Mound & The Sacred Datura, Viewzone.

http://www.viewzone.com/mothman.html. Posted 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

Derbyshire, David. 2003. Found in Wales, folklores harbinger of death,

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/science-news/3311501/Found-in-Wales-folklores-harbinger-

of-death.html. Retrieved 07-12-2010.

Dixon, Deborah. 2007. A benevolent and sceptical inquiry: exploring Fortean Geographies with the

Mothman, Cultural Geographies 2007 (14): 189-210.

Frazer, J.G. 1922. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. New York: The MacMillan

Company.

Fuseli, Henry. 1795. Review of Archives of Entomology, Analytical Review XXI (May 1795): 523-4.

Goethe, Johan Wolfgang von. [1808]. 1980. Faust. Tr. Alice Raphael. Norwalk: The Easton Press.

Hibben, Frank. 1975. Kiva Art of the Anasazi Pottery Mound. Las Vegas: KC Publications.

Jones, Colin. n.d. How Not to Laugh in the French Enlightenment: The Saint-Aubin Livre de Caricatures.

Chicago: University of Chicago Modern France Workshop.

http://fcc.uchicago.edu/pdf/enlightenment.pdf. Retrieved 07-25-2010.

Kay, Paul T. 2005. Ancient Voicesmurals and pots speak. DATURA: A Poster Presentation for the 70

th

Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology. Salt Lake City.

http://paultkay.info/DATURA_05_08_2006.pdf. Retrieved 07-25-2010.

Keel, John. 1975. The Mothman Prophecies. New York: Tom Doherty Associates.

Law, L.A. 1900. Death and Burial Customs in Wiltshire, Folk-lore. Transactions of the Folk-lore

Society. XI:1 (March 1900): 344.

Lentzsch, Franziska et.al. 2005. Fuseli: The Wild Swiss. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess.

LeRose, Chris. 2001. The Collapse of the Silver Bridge, West Virginia Historical Society Quarterly

XV:4 (Oct 2001).

Linnaeus, Carolus. 1758. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera,

species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis. 10

th

Ed. Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii.

Mauris, Patrick. 1996. Essai sur les papilloneries humaines. Paris.

9

Milton, John. 1897. [1637] Lycidas. ed. J. Phelps Fruit. Boston: Ginn & Company.

Nickell, Joe. 2002. Mothman Solved! Skeptical Inquirer March/April 2002: 20-21.

_____. 2004. The Mystery Chronicles: More Real-Life X-Files. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Petrenko, Yuri B. 1973. Forerunner of the Flying Lady of Vietnam? Flying Saucer Review 19:2

(March/April 1973): 29-30.

Radford, Jonathan. n.d. Italian Hawk Moths. http://www.lifeinitaly.com/garden/hummingbird-moths.asp.

Retrieved 07-12-2010.

Sergent, Donnie Jr. & Wamsley, Jeff. 2002. Mothman: The Facts Behind the Legend. Point Pleasant, WV:

Mothman Lives Publishing.

Schaafsma, Polly. 1980. Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. Santa Fe/Albuquerque: School of American

Research/University of New Mexico Press.

Schiff, Gert et.al. 1975. Henry Fuseli 1741-1825. London: Tate Gallery.

Sherwood, John C. 2002. Gray Barkers Book of Bunk: Mothman, Saucers and MIB, Skeptical Inquirer

May/June 2002: 39-44.

Vergil (P. Vergilius Maro). 19 BCE. Aeneid. tr. John Dryden.

Weinglass, David H. (ed.) 1982. The Collected English Letters of Henry Fuseli. London: Kraus

International Publications.

Wolff, Neils L. 1971. Lepidoptera. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard.

Wood-Martin, W.G. 1902. Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland: A Folklore Sketch: A Handbook of Irish

Pre-Christian Traditions. Vol. II. New York: Longmans, Green & Co.

10

Notes

1

For an excellent summary and presentation of primary sources, see Sergent & Wamsley.

2

See Dixon, 2007, esp. 195-207.

3

Quoted in Keel, 1975: 60.

4

Quoted in Keel, 1975: 60.

5

Quoted in Keel, 1975: 244.

6

Described by witness Roger Scarberry (Keel, 1975: 560).

7

See Keel, chapter 18 Something awful is going to happen (1975: 244-56). For an analysis of the

collapse of the Silver Bridge, see LeRose.

8

See also Nickell, 2002 and Sherwood, 2002.

9

Coleman, 2007.

10

1975: 27.

11

1975: 26-29. On the latter see also Petrenko, 1973 and Coleman, 2002: 31.

12

2002: 26-37.

13

The one exception being the Arlington, VA sighting, described as having large red-orange eyeballs.

(Quoted in Coleman, 2002: 31). Interestingly, this sighting, out of all of those mentioned above, is in

closest geographic and temporal proximity to the West Virginia Mothman sightings.

14

Readers may be most familiar with his painting The Nightmare, which depicts an incubus on the chest of

a sleeping woman, with the white head of a mare in the background.

15

Sometimes also referred to as Titania Awakes, Surrounded by Attendant Fairies, clinging rapturously to

Bottom, still wearing the Asss head.

16

1956: 103. See also Schiff, et.al.: 62-3. It is difficult to discern exactly which figure Antal is referring to

here, although in my opinion it is most likely XENIES, who spouts the lines With tiny sharply pointed

claws/As insects we appear/Satan, our dear papa/We lovingly revere. (Goethe: 167). It is interesting to

note also that the wedding occurs on Walpurgisnacht.

17

Letter from Miss Margaret Patrickson to Allan Cunningham, 14-Sep-1830, quoted in Weinglass: 532-3.

18

See Fuseli: 1795.

19

See Letter to Sydenham Edwards 14-Sep-1816, quoted in Weinglass: 419.

20

Letter to Robert Balmano 15-Oct-1807, quoted in Weinglass: 362. There is also some evidence that he

was in possession of parts of Jan Christian Sepps Beschouwing der wonderen Gods, in de minstgeachte

schepzelen : of Nederlandsche insecten, naar hunne aanmerkelyke huishouding, verwonderlyke

gedaantewisseling en andere wetenswaardige byzonderheden, volgens eigen ondervinding beschreeven,

naar 't leven naauwkeurig getekend, in't koper gebracht en gekleurd, a massive Dutch entomological

treatise with over 400 illustrated color plates. (See Weinglass: 483)

21

Weinglass, 1982.

22

Letter to John Knowles, quoted in Weinglass: 370.

23

See Linnaeus, 1758: I:490.

24

Its wingspan is around six inches, and is the second-largest insect in Europe. (Badenloch: 231)

25

Badenloch: 233.

26

Wolff, 1971.

27

Interestingly, it is also during this time that the initial events of 1966 took place, the Scarberrys and

Malettes sighting occurring on November 15

th

.

28

Aeneid VI: 297.

29

Vergil, Aeneid VI: 323.

30

Milton, Lycidas, l. 75.

31

Badenloch: 235.

32

Badenloch: 235.

33

Radford; Badenloch: 236.

34

Badenloch: 236.

35

Radford; Badenloch: 236.

36

Wood-Martin: 80.

37

See Frazer: 11-37; Child & Child: 138-9. On the caterpillar in Britain, see also Derbyshire.

38

Law: 344.

39

236.

11

40

Lentzsch, et.al.: 136.

41

See for example his works Queen Mab (1814), wherein [Queen Mab] balances in a dancing pose in a

carriage or sleigh drawn by fat moths in a state of metamorphosis [Lentzsch, et.al.: 124], and Puck basking

asleep by the Embers of a Country Chimney (c. 1793-1810).

42

126.

43

115, n.100.

44

12-13.

45

From a purely artistic perspective, it can also be shown that Moth-men figured in the art and religion of

fourteenth century Pueblo Indians in New Mexico (see Figs. 8 & 9, below). Though it is difficult to extract

their exact role and how it might have informed (or not) the modern Mothman mythos, Schaafsma has

stated that the subject matter consists of ceremonial and ritual themes into which elaborately attired

humans, birds, and abstract designs are incorporated. [] This is a highly meaningful art, full of graphic

portrayals and symbolic content. (251; See also Hibben) From a symbolic standpoint, there seems to be a

connection between these depictions and an American moth, the night flying hawk moth Manduca sexta.

(see Kay: 4ff. and David)

Figs. 8 & 9. Moth-Men murals from Pottery Mound near Las Lunas, NM, c. 1350. See Kay, 4ff. for more depictions.

Also of note in terms of art are the works of Charles Germain de Saint-Aubin, a contemporary of Fuselis

who illustrated a work called Essai de papilloneries humaines (Essay on the Human Antics of Butterflies

[or Moths]), in which butterflies and moths are shown playfully engaged in various forms of human

activity, though these seem to have little to do with folklore. (Jones: 9; see also Mauris)

Figs. 10 & 11. Ballet Champtre and Le Duel, from Essai de papilloneries humaines by Charles Germain de Saint-Aubin (c. 1750).

46

2007. Indeed, even Robert Roachs statue of the Mothman that stands in Point Pleasant today (Fig. 12)

bears little resemblance to the witnesses descriptions.

47

Nickell, 2002: 20.

48

See Keels comments on the litany of deaths, suicides, divorces, mental illness and other calamities

following the events of 1966-7 (265-6). For commentary, see Dixon: 196-202; Nickell, 2002: 20;

Sherwood.

49

202.

50

Dixon: 204.

You might also like

- EVERGREEN MEDIA HOLDINGS/ BRITTLE, V LORRAINE WARREN Et AlDocument33 pagesEVERGREEN MEDIA HOLDINGS/ BRITTLE, V LORRAINE WARREN Et AlEMGNo ratings yet

- Compressions, The Hydrogen Atom, & Phase ConjugationDocument29 pagesCompressions, The Hydrogen Atom, & Phase ConjugationBryan Graczyk100% (1)

- Collection of Ufo Reports From Around The WorldDocument53 pagesCollection of Ufo Reports From Around The WorldparanormapNo ratings yet

- The Mothman A Folkloric PerspectiveDocument11 pagesThe Mothman A Folkloric Perspectiversharom3246705No ratings yet

- The Mothman A Folkloric PerspectiveDocument11 pagesThe Mothman A Folkloric Perspectiversharom3246705No ratings yet

- In Six Days: The Genesis Creation DebateDocument35 pagesIn Six Days: The Genesis Creation Debatersharom3246705100% (1)

- M U T U A LDocument25 pagesM U T U A LSAB78No ratings yet

- Headpress 02Document60 pagesHeadpress 02Steve BesseNo ratings yet

- Saucers and The Sacred - The Folklore of UFO NarrativesDocument52 pagesSaucers and The Sacred - The Folklore of UFO NarrativesTim BrighamNo ratings yet

- 04 Cooling SystemDocument25 pages04 Cooling SystemvixentdNo ratings yet

- Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship From VHS to File SharingFrom EverandKiller Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship From VHS to File SharingNo ratings yet

- M U T U A L U F o NDocument26 pagesM U T U A L U F o NSAB78100% (1)

- Flying Saucer Review - Janet & Colin Bord - Billy Meier 1980Document4 pagesFlying Saucer Review - Janet & Colin Bord - Billy Meier 1980Oliver HinojosaNo ratings yet

- Ufos & Alien Contact - Two Centuries of MysteryDocument571 pagesUfos & Alien Contact - Two Centuries of MysteryVideos googledriveNo ratings yet

- ManichaeismDocument168 pagesManichaeismpstrl100% (16)

- PURSUIT Newsletter No. 36, Fall 1976 - Ivan T. SandersonDocument28 pagesPURSUIT Newsletter No. 36, Fall 1976 - Ivan T. SandersonuforteanNo ratings yet

- MUFON UFO Journal - October 1992Document24 pagesMUFON UFO Journal - October 1992Carlos Rodriguez100% (2)

- UFOs and Popular Culture James LewisDocument435 pagesUFOs and Popular Culture James LewisDiego AntoliniNo ratings yet

- Cahiers Du Cinema in English 3 1966Document75 pagesCahiers Du Cinema in English 3 1966CarlosChaconNo ratings yet

- MUFON UFO Journal - February 1990Document24 pagesMUFON UFO Journal - February 1990Carlos RodriguezNo ratings yet

- The Marcia Smith StoryDocument6 pagesThe Marcia Smith StoryLin CornelisonNo ratings yet

- M U T U A LDocument25 pagesM U T U A LSAB78No ratings yet

- Swords ReportDocument4 pagesSwords ReportDanteNo ratings yet

- The A.P.R.O. Bulletin Nov-Dec 1972Document9 pagesThe A.P.R.O. Bulletin Nov-Dec 1972Nicholas VolosinNo ratings yet

- Gender Displacement in Contemporary Horror (Shannon Roulet) 20..Document13 pagesGender Displacement in Contemporary Horror (Shannon Roulet) 20..Motor BrethNo ratings yet

- The Mothman An ArchetypeDocument4 pagesThe Mothman An ArchetypexdarbyNo ratings yet

- International: Alien Humanoid or Earthly Fetus?Document2 pagesInternational: Alien Humanoid or Earthly Fetus?charlesfortNo ratings yet

- PURSUIT Newsletter No. 82, Second Quarter 1988 - Ivan T. SandersonDocument52 pagesPURSUIT Newsletter No. 82, Second Quarter 1988 - Ivan T. Sandersonufortean100% (1)

- Ultima Underworld II - A Safe Passage Through Britannia PDFDocument28 pagesUltima Underworld II - A Safe Passage Through Britannia PDFEdgar Sánchez FuentesNo ratings yet

- Nashional Investigations Commitment On Space PhenomenalDocument6 pagesNashional Investigations Commitment On Space PhenomenaltactocNo ratings yet

- Anomaly 12 - John Keel - Unpublished (Rendition)Document5 pagesAnomaly 12 - John Keel - Unpublished (Rendition)Eric KilnNo ratings yet

- 1956 11 15 Saucerian Bulletin Vol-1#5Document6 pages1956 11 15 Saucerian Bulletin Vol-1#5Keith S.No ratings yet

- DC Comics Sample Script Final 3 18Document5 pagesDC Comics Sample Script Final 3 18Conspirador CromáticoNo ratings yet

- 1990 - Persinger - Journal of Ufo Studies - The Tetonic Strain Theory As An Explanation For Ufo PhenomenaDocument33 pages1990 - Persinger - Journal of Ufo Studies - The Tetonic Strain Theory As An Explanation For Ufo Phenomenaapi-260591323No ratings yet

- Aesthetic Deviations: A Critical View of American Shot-on-Video Horror, 1984-1994From EverandAesthetic Deviations: A Critical View of American Shot-on-Video Horror, 1984-1994No ratings yet

- Novel North American Hominins Final PDF DownloadDocument41 pagesNovel North American Hominins Final PDF DownloadRichard Bachman100% (1)

- The A.P.R.O. Bulletin Mar-Apr 1972Document9 pagesThe A.P.R.O. Bulletin Mar-Apr 1972Nicholas VolosinNo ratings yet

- The Book of Beasts: Folklore, Popular Culture and Nigel Kneale’s ATV TV SeriesFrom EverandThe Book of Beasts: Folklore, Popular Culture and Nigel Kneale’s ATV TV SeriesNo ratings yet

- Build Your OwnDocument41 pagesBuild Your Ownandrew_jkd100% (14)

- The A.P.R.O. Bulletin Jan-Feb 1972Document9 pagesThe A.P.R.O. Bulletin Jan-Feb 1972Nicholas VolosinNo ratings yet

- UFOs and IntelligenceDocument679 pagesUFOs and IntelligenceJoão Francisco SchrammNo ratings yet

- Halloween Vocabulary Esl Unscramble The Words Worksheets For Kids PDFDocument4 pagesHalloween Vocabulary Esl Unscramble The Words Worksheets For Kids PDFEdurne De Vicente Pereira0% (2)

- Alien Abduction: A Medical Hypothesis: David V. ForrestDocument12 pagesAlien Abduction: A Medical Hypothesis: David V. ForrestAnónimo 00111010101001110No ratings yet

- Carney Jeff - Alien Abductions A Critical ReaderDocument81 pagesCarney Jeff - Alien Abductions A Critical ReaderpalomitachanNo ratings yet

- Magonia - No 39 - 1991 04Document7 pagesMagonia - No 39 - 1991 04nevilleNo ratings yet

- Soal MtcnaDocument4 pagesSoal MtcnaB. Jati Lestari50% (2)

- Hopkinsville Goblins Aug 1955Document14 pagesHopkinsville Goblins Aug 1955Juan CabezasNo ratings yet

- Canadian UFO Report - Vol 1 No 7 - 1970Document48 pagesCanadian UFO Report - Vol 1 No 7 - 1970ratatu100% (1)

- Milligan BigfootDocument17 pagesMilligan BigfootTony WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 011 Dec-Jan 1960-61Document8 pages011 Dec-Jan 1960-61edicioneshalbraneNo ratings yet

- American Twilight: A Memoir of Another WarDocument125 pagesAmerican Twilight: A Memoir of Another WarSteven Schmidt100% (1)

- Sunlite: Shedding Some Light On Ufology and UfosDocument25 pagesSunlite: Shedding Some Light On Ufology and UfosMarihHolasNo ratings yet

- 1949, Norwood, Ohio Searchlight UFO IncidentDocument4 pages1949, Norwood, Ohio Searchlight UFO IncidentMary DiazNo ratings yet

- America's Unrecognized UFO Experts by John A. KeelDocument7 pagesAmerica's Unrecognized UFO Experts by John A. KeelJerry Hamm100% (3)

- 'U.F.O.Investigator: Thecase ForlifeonmarsDocument8 pages'U.F.O.Investigator: Thecase ForlifeonmarsedicioneshalbraneNo ratings yet

- M U T U A LDocument25 pagesM U T U A LSAB78100% (1)

- Magonia - No 24 - 1986 11Document6 pagesMagonia - No 24 - 1986 11nevilleNo ratings yet

- AFU 19520915 APRO Bulletin v1 n2 (CUFOS)Document16 pagesAFU 19520915 APRO Bulletin v1 n2 (CUFOS)ScooterKatNo ratings yet

- L.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsDocument28 pagesL.A. Noir Gary J. Hausladen and Paul F. StarrsIzzy MannixNo ratings yet

- Florida Sighting Stirs Debate ' I: NICAP PhotoDocument4 pagesFlorida Sighting Stirs Debate ' I: NICAP PhotoedicioneshalbraneNo ratings yet

- Years Of: Lose NcountersDocument4 pagesYears Of: Lose NcountersIguazuNo ratings yet

- NEW UFO'S BUZZ WORLD AIRPORTS by John A. KeelDocument6 pagesNEW UFO'S BUZZ WORLD AIRPORTS by John A. KeelJerry Hamm100% (2)

- Citizens' Fact-Finding Commission To Investigate Human Rights Violations of Children in NebraskaDocument2 pagesCitizens' Fact-Finding Commission To Investigate Human Rights Violations of Children in NebraskaCrystal ScurrNo ratings yet

- Concertina 18Document1 pageConcertina 18rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- FEN2ASCIIDocument4 pagesFEN2ASCIIrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Innovacion CienciaDocument16 pagesInnovacion Cienciarsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Modern Science and The Bible: The Heavens Declare The Glory of God. Psalm 19:1Document50 pagesModern Science and The Bible: The Heavens Declare The Glory of God. Psalm 19:1rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Shadow To Reality 1Document335 pagesShadow To Reality 1rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Creation/Evolution: Issue 33 Winter 1993Document56 pagesCreation/Evolution: Issue 33 Winter 1993rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Dendroid ESWA 2014 PPDocument29 pagesDendroid ESWA 2014 PPrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Tyrol ItDocument14 pagesTyrol ItneurussNo ratings yet

- Article Reprint: Too Much Activity On Day Six?Document2 pagesArticle Reprint: Too Much Activity On Day Six?rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- DanielDocument252 pagesDanielrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- THE KINGDOM REDEFINEDDocument53 pagesTHE KINGDOM REDEFINEDrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- AIDS 2006 EnglishDocument8 pagesAIDS 2006 Englishrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- SEVENTH DAY STILL CONTINUINGDocument2 pagesSEVENTH DAY STILL CONTINUINGrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Broadcaster Article2Document4 pagesBroadcaster Article2rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Shadow To Reality 1Document335 pagesShadow To Reality 1rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- On The Rabbinical Approximation Of: Department of Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 52900 Ramat-Gan, IsraelDocument10 pagesOn The Rabbinical Approximation Of: Department of Mathematics, Bar-Ilan University, 52900 Ramat-Gan, Israelrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Gerd Gastroesofageal Reflux DiseaseDocument6 pagesGerd Gastroesofageal Reflux DiseaseMuhammad Benny SetiyadiNo ratings yet

- Kremer The Concept of Cellsymbiosis TherapyDocument6 pagesKremer The Concept of Cellsymbiosis Therapyrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Protexid Paper 1Document6 pagesProtexid Paper 1rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- BibleInterpretation CKeenerDocument88 pagesBibleInterpretation CKeenerrvturnageNo ratings yet

- Protexid Paper 1Document9 pagesProtexid Paper 1rsharom3246705No ratings yet

- F MatterDocument19 pagesF Matterrsharom3246705No ratings yet

- Vedic Mathematics, Teaching An Old Dog With New TricksDocument24 pagesVedic Mathematics, Teaching An Old Dog With New TricksmruthyubNo ratings yet

- Technoir Transmission GuideDocument4 pagesTechnoir Transmission GuideAlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Fa#4 Ged0109Document1 pageFa#4 Ged0109sayuwu uwuNo ratings yet

- "Thought Bubble" - Anime Fanzine Issue 04 - December 2015Document30 pages"Thought Bubble" - Anime Fanzine Issue 04 - December 2015Thought Bubble100% (1)

- Retail Institutions by Ownership: Retail Management: A Strategic ApproachDocument18 pagesRetail Institutions by Ownership: Retail Management: A Strategic ApproachVishakhNo ratings yet

- Mardi GrasDocument23 pagesMardi Grasjayjay1122No ratings yet

- The Hobbit Battle of the Five Armies 1080p WEBRip x264 Movie DownloadDocument3 pagesThe Hobbit Battle of the Five Armies 1080p WEBRip x264 Movie DownloadYneboy YneboyNo ratings yet

- 10 Gross Motor Movement and Greeting Songs for KidsDocument13 pages10 Gross Motor Movement and Greeting Songs for KidssaraNo ratings yet

- Menu 15 de Septiembre Del 2019Document19 pagesMenu 15 de Septiembre Del 2019gabriel_sulbaránNo ratings yet

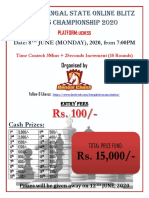

- Bca Online Blitz Brochure Final-2Document3 pagesBca Online Blitz Brochure Final-2rikNo ratings yet

- Chest WorkoutDocument2 pagesChest Workoutapi-267927024No ratings yet

- Vocab 15Document2 pagesVocab 15api-278257993No ratings yet

- Adsl Router User ManualDocument34 pagesAdsl Router User ManualRolando NoroñaNo ratings yet

- Wi-Fi Jamming Using Raspberry Pi: ISSN: 1314-3395 (On-Line Version) Url: Http://acadpubl - Eu/hub Special IssueDocument8 pagesWi-Fi Jamming Using Raspberry Pi: ISSN: 1314-3395 (On-Line Version) Url: Http://acadpubl - Eu/hub Special IssueSarangNo ratings yet

- Project Document Aptech Sem 3Document31 pagesProject Document Aptech Sem 3Khanh Vo Hong100% (4)

- The Work of The (Festive) Devil - Angela MarinoDocument18 pagesThe Work of The (Festive) Devil - Angela MarinoLuisa MarinhoNo ratings yet

- Adjective Clause Worksheet EslDocument4 pagesAdjective Clause Worksheet EslEdwin Logroño0% (1)

- Academic Reading Test 2Document8 pagesAcademic Reading Test 2Nahoo Asteraye TsigeNo ratings yet

- The Charter Oak Brunch MenuDocument1 pageThe Charter Oak Brunch MenuEllenFortNo ratings yet

- Online Stocks User Guide IDocument22 pagesOnline Stocks User Guide ITan Teck HweeNo ratings yet

- The Monster Next Door L4 STORYDocument5 pagesThe Monster Next Door L4 STORYOrapeleng MakgeledisaNo ratings yet

- Point To Point Pay Fixation Chart From 1972 To 2017Document8 pagesPoint To Point Pay Fixation Chart From 1972 To 2017Sheraz AslamNo ratings yet

- Kung-Fu Panda's Critical Analysis (From The Perspective of Coaching Only)Document4 pagesKung-Fu Panda's Critical Analysis (From The Perspective of Coaching Only)Muhammad ZulfiqarNo ratings yet

- Target Market of SonyDocument30 pagesTarget Market of SonyNguyễn Quỳnh Huyền LinhNo ratings yet

- Scrapyard 2Document6 pagesScrapyard 2Mrunal shirtureNo ratings yet

- Final Writing AssignmentDocument10 pagesFinal Writing AssignmentJoao BaylonNo ratings yet

- Authority TO CONDUCT Activity: Godoy Elementary SchoolDocument8 pagesAuthority TO CONDUCT Activity: Godoy Elementary SchooljoraldNo ratings yet