Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chem Tech Case Study

Uploaded by

Adeel KhanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chem Tech Case Study

Uploaded by

Adeel KhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Crafting sense at ChemTech

Peter Brgi and Johan Roos

This case allows the reader to consider if and how conventional approaches to strategy making may limit

the degree to which firms prepare for uncertainty and change. It shows ChemTech,1 a leading specialty

chemicals company supplying the flavours and fragrances industry, wrestling with conservatism in its

strategy-making processes, and adopting an innovative approach crafting sense that aims to cultivate overall firm readiness to deal with emergent change.

l l l

The challenge from above

It was two months before the Global Strategy

Rollout for ChemTech and corporate top management were not happy. The new divisional strategies are too similar to the ones from the previous

planning cycle, the top corporate strategy officer

observed. More importantly, he noted, the plans

didnt address the quickening pace of change in

their industry, or even the obvious changes in the

business environment in the intervening years.

How, he wondered, could he help divisional management recognise that their individual plans were

out of sync with a rapidly changing business environment, and in need of vigorous new directions?

And how could he encourage them to see their

strategies not as a trajectory they were locked into,

but rather as a resource permitting adaptive action

when the unforeseeable occurred?

ChemTech a mid-sized specialty chemicals

firm with a worldwide workforce of approximately

4,000 was experiencing a problem typical of the

growing number of organisations facing disruptive

change in the business environment. It was

striving to balance the disciplining effects of

The name is fictitious, but the company, its situation, and our

experience with it are real.

planning against the need for innovative, adaptive

action. For ChemTech, like most organisations, the

dilemma of planning vs. adaptability was deeply

problematic, but finding a way of reconciling these

seemingly opposed demands was crucial for the

firms long-term success. How could corporate

management help the divisions work towards finding such a way?

Controlling the details of

implementation

Formal strategic planning was a relatively new

phenomenon at ChemTech. In the words of one of

the senior managers,

there really wasnt any formal strategy at ChemTech

until about five years ago. Up to that point we simply

made money by producing high-quality, desirable

products for an industry that was organised like a sort

of big club in which everyone had a place and a role.

This cosy situation had changed when corporate

management decided that a more formal planning

process was needed, and instituted a tri-yearly

process of developing strategic plans for the different divisions of the corporation. The first of these

tri-yearly strategy-making cycles, undertaken in

1999, was internally referred to as the X3

This case was prepared by Peter Brgi and Johan Roos, Imagination Lab Foundation, Switzerland (www.imagilab.org). It is

intended as a basis for class discussion and not as an illustration of either good or bad management practice. Peter Brgi

and Johan Roos, 2004. Not to be reproduced or quoted without permission.

CASE STUDY

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 1

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 2

Crafting sense at ChemTech

Exhibit 1

Imagination Lab Foundation philosophy

Imagination Lab is a Swiss-based, non-profit research foundation that develops and diffuses

ideas about innovative strategic management practice. We see a business world in which

routine, inefficient communication and a lack of coherence are only the symptoms of a

deeper problem: that people in organisations struggle to create meaning and deal with the

unexpected.

For more details see www.imagilab.org.

strategies. Because each of the three divisions had

a different market focus, they were allowed some

autonomy in developing these X3 strategies.

However, all had used commonly accepted

strategy-making tools in their efforts during the

X3 cycle of strategy development.

The Fragrances division had reviewed a variety

of financial performance indicators (prior revenue,

costs, projected sales) from their many clients, segmenting their client base into various grades, and

especially identifying preferred clients, who represented more than 70 per cent of the potential revenue stream. This analysis had led them to

conclude that clients who fell into this segment

would provide the best forward cumulative EVA

for their stakeholders. Intensified R&D (more staff,

increased budget), and a new HR initiative for

hiring and retraining staff to align their workforce

with organisational performance targets, supported

the strategic focus on these preferred clients.

The Flavors division had reviewed similar financial performance indicators, but had supplemented

this analysis with a detailed market segmentation

study. This study identified specific sub-industries,

and for each of these had calculated overall market

size, average client size, and projected growth

potential. Because their market was highly fragmented (the two largest players together, both

globally recognised organisations, accounted for

only 4 per cent of total market sales), the emphasis

in the Flavors division analysis was more on

projected growth rates in different sub-segments

rather than on ideal clients in them. The Flavors

division had therefore concluded that their

strategy would consist of concentrating on these

high projected growth rate sub-segments in order

to achieve the returns that their corporate parent

expected of them.

As with its other two sibling divisions in

ChemTech, the Specialty Chemicals division had

also completed a comprehensive financial review of

its performance. Specific targets for its contribution

to the corporate bottom line had been set, but its

strategic situation was especially complex. For historical reasons, this division had evolved to serve

both internal and external clients. It provided basic

components to the Fragrances and the Flavors divisions, as well as to external organisations which

were often the direct competitors of these sibling

divisions. The ability to judge the financial tradeoffs (both year-on-year as well as in terms of more

extended time horizons) involved in straddling

internal and external markets had become compromised by the growing size of the organisation,

as well as by accelerating changes in alliances

among competitors. A decision had therefore been

taken to manage this complex situation with the

Balanced Scorecard approach. The leadership

hoped that this could help neutralise any tendency

to develop a bias towards either the internal or

external clients that might not serve ChemTechs

overall long-term interests.

By early 2002, the second of the tri-yearly cycles

of strategy development was just nearing completion. The resulting strategic plans, called the

X6 strategies, had not departed in any radical way

from the previous ones (see Exhibit 2 below).

In fact, many in the firm had felt that, if the X3

strategies had suffered any deficiency, it had not

been in the analysis but in the way the strategy

had been used. Thus, interviews with executives and

management in early 2002 were very consistent

across all divisions in emphasising that the strategic planning groups were concerned with controlling the details of how the new X6 strategy would

be implemented. One senior manager said:

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 3

Crafting sense at ChemTech

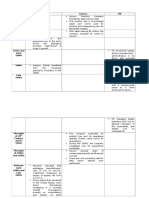

Exhibit 2

Summary of situation in ChemTech

Division

Market

Standing in

ChemTech

X3 Strategy

X6 Strategy

Means of

dissemination

Fragrances

Perfumes

Oldest division

of corporation,

very high profile

Preferred client,

determined via

financial

measurements

Review and

update X3

PowerPoint slides

of financial graphs,

mission and

objectives statements,

specific actions to be

taken

Flavors

Foods

Newest division,

problem child

Detailed market

segment analysis

Review and

update X3 with

more detailed

analysis

PowerPoint slides

of financial graphs,

mission and objectives

statements, specific

actions to be taken

Specialty

Chemicals

Chemicals

Basic

engineering,

corporate-wide

logistics and

budgeting

Market analysis,

begin Balanced

Scorecard

approach

Extend

Balanced

Scorecard

PowerPoint slides of

Balanced Scorecard

components

The strategic vision of X3 was not lived through

people. People were reassured that we had such a plan,

but it wasnt critical to what they did on a daily basis.

We now want to bring it closer, bring it home to

people, and make it tangible in their behaviour.

A senior member of another strategy development

team put it this way: The X3 didnt address

implementation. In fact, we had success with the

strategy despite the lack of implementation focus.

And, in the words of the number two executive in

the largest division, The Balanced Scorecard is the

primary input to our strategy. It drives the level

of detail about what has to be done down very

far its a very detailed process.

But there were clearly dissenting voices who

argued that strategy development had quickly

become routinised and bureaucratic, and that the

obsession with controlling the details of implementation carried with it diminishing returns. A

senior Vice President at the division using the

Balanced Scorecard approach observed, its a

heavy process. Theres so much formalism that it is

quite difficult to use. And, although they were in

the minority, there were some divisional managers

who shared the top corporate strategy officers

corporate impression that the X6 strategies were

too similar to the X3 ones. After talking about the

review of the competition they had conducted to

develop their X6 plan, the senior strategist in one

division had declared, Porter would be proud of

us.1 A senior colleague from another division had

promptly rejoined, . . . and the way weve gone

about it is ridiculous.

Crafting sense2: combining

thinking and manual skills

From a vantage point overseeing all corporate-wide

strategy development, the corporate strategy officer

at ChemTech had recognised that the divisional

processes had stagnated, and he began to challenge the content of the divisions strategic plans.

One way to remedy the situation, he believed,

called for a parallel process that might yield

The individual was referring to the prescriptions on strategy

found in Competitive Strategy by M. Porter (1980: Free Press).

See the forthcoming book on crafting sense by Johan Roos and

Peter Brgi.

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 4

Crafting sense at ChemTech

Exhibit 3

The crafting sense approach

Combining established principles from psychology and education, the basic idea of the

crafting sense approach is to combine peoples thinking and manual skills and use this

capacity to interpret, deal with, and communicate business issues. When applied to

complex business issues, like strategy making or innovation, this approach creates the

conditions for deep comprehension, strong commitment, and improved communications.

Making sense by crafting sense can be an immersive, emotional and gratifying activity,

which enables managers to learn, interact, and relate to one another in new ways.

See J. Roos, Sparting strategic imagination, Sloan Management Review, Fall 2004

(forthcoming).

Exhibit 4

Different assumptions in strategy-making

Existing approach already used by each division

Crafting Sense approach

l Begin by analysing the external world

l Begin by understanding your organisation

l One can make decisions about the future

l The future is unpredictable and change is a

fundamental condition of life

l Groups at every level of an organisation have

l One should control the details of implementation

to interpret strategy

l Human social interactions often produce novel,

l Strategy making as a process should be routine

emergent situations and forces

and systematic

l Encourage groups to discover and embody

l Strategy is impersonal, emotionless

good strategic behaviour

and non-committal

additional, complementary content. To this end

corporate management asked Imagination Lab

Foundation to design and stage workshops for

the strategists and senior managers of each of the

three divisions. In line with the Imagination Lab

philosophy these workshops applied an approach

that combines peoples thinking and manual skills:

crafting sense (see Exhibit 3). When crafting sense,

people physically construct a representation of the

issue at hand (use of kinesthetic information),

which is seen and visualised (use of visual information), as well as verbally enriched and evaluated

(use of narrative information).

To help these managers to craft sense,

Imagination Lab facilitators selected and applied

a workshop product in which managers use a

variety of LEGO materials in many colours, sizes

and shapes as a communication tool.2

The strategy workshops

Instead of emphasising the future, the facilitators

designed the workshops to focus on their organisations current strategic situation (see Exhibit 4).

The workshops designed by Imagination Lab

were all similarly structured in three basic phases:

(1) looking inside, (2) looking outside, and (3)

For the conceptual background of this technique see J. Roos,

B. Victor and M. Statler, Playing seriously with strategy, Long

Range Planning, forthcoming, December 2004.

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 5

Crafting sense at ChemTech

Exhibit 5

Workshop structure

Looking inside

The first phase of the workshop focused on organisational identity. Participants were asked to

use the 3D materials to construct individual representations of the organisations identity not its

physical facilities, but its essential characteristics, key functions, internal relationships, structures,

most prominent features, central attributes, etc. After each person had discussed the representation

they had built with the other members, the group was asked to work together and collectively build

a single, joint version of the organisations identity. When finished, it was placed in the middle of the

worktable.

Looking outside

The second phase focused on the business world outside of the organisation. Each participant was

asked to use the 3D materials to build representations of the most important factors that had an

impact on the success of the business (whether positively or negatively, directly or indirectly),

including clients, regulatory bodies, competitors, new technologies, etc. After each person had

discussed what they had built, the group chose which elements to place around the model of the

organisation, and where and how to place it. Each placement showed how that element related to

the enterprise supporting it, obstructing it, enabling it, etc. Once this was completed, participants

were asked to use the 3D materials to build connections among all the elements on the table, to

show the most important influences, networks, and interactions among them.

Identifying guiding principles for action

The final phase of the workshop focused on how to best respond to the changing dynamics

between the inside and outside worlds. In this phase participants were asked to identify a series

of likely future events that could affect the organisation. They then systematically discussed the

implications of each event for the organisation, including what they thought the best response

for the organisation should be in each scenario. Facilitators helped the participants then identify

patterns in these responses, and consolidate these into succinct ideas or phrases. These ideas

then became guiding principles which provided direction for the groups strategic action.

identifying guiding principles for action. These were

explained to ChemTech as shown in Exhibit 5.

Emerging content

Each of the crafting sense workshops stimulated

interesting and unexpected ideas, which, in turn,

yielded new inputs to the strategy-making process.

Fragrances division

The construction of a collective identity for this

division focused on a conceptualisation of the

organisations workflow. The structure the group

built was very linear, and was laid out along a

single long axis, which began in an innovation

engine and culminated in a set of stairs which

rose up to a client project, represented by a large

animal. A small, mobile, piloted vehicle, bristling

with emblems of the specialty products that this

division provided to clients, was moving along the

axis. It represented the continuous efforts to bring

value to clients, and when it was produced, the

participants united in seeing their organisation in

these common terms.

In the next phase of the workshop, the key

element that attracted most attention was the

building of a large windmill or propeller representing the winds of change which were sweeping

across the industry, and which were likely to

change things in the near future. This was by far

the largest and most imposing construction on the

table, and it occasioned considerable discussion

about how much the current X6 strategy reflected

these forces of change in the organisations

environment.

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 6

Crafting sense at ChemTech

Finally, the workshop generated several key

guiding principles. Create love stories with clients.

Take advantage of industry consolidation. Know ourselves intimately. The first two of these ideas sprang

directly from the way in which the group had

imagined the identity of the organisation namely

as a process which had to be well controlled (hence

the need to know ourselves intimately), and which

was focused entirely on the delivery of products

that delighted their customers (hence the need to

create love stories with clients). Most importantly,

these guiding principles were expressions of ideas

absent from the X6 strategy document, which had

focused entirely on a variety of financial metrics

and analyses as support for the preferred client

strategy. In light of the guiding principle to take

advantage of industry consolidation, one participant

stated the group is going to have to update the

X6 plan to take into account some of these likely

competitive challenges.

In the final discussions, the group became

acutely aware of omissions in the X6 plan. With

their Corporate Vice President sitting at the head

of the table, one of those who had worked to draft

the plan stated bluntly: The X6 strategy should be

anticipating and reacting to the winds of change,

but all weve really put into that plan is how to

take care of todays business. Another person said:

If you look at the X6 plan, where is the love

part? Where is the emotional part that is such a big

part of our products? Its not there. And a third

person, reflecting on the vivid representation of

the organisation in its complex competitive landscape, said: One of the things thats clear to me

is why all the two-dimensional ways of communicating strategy, like charts and laptop slide

shows, just dont work. To really understand what

our strategy should be, you have to experience it

like this, in 3-D.

When the divisional strategy finally rolled out

later that year, the basic structure of a preferred

client strategy remained in place, but it was supplemented in two important ways. First, the strategists had concluded that they would have to adopt

a new perspective towards their strategic plan: no

longer seeing it as a predetermined set of activities,

they would regard it as a key point of reference

which left them with enough tactical room to take

advantage of opportunities where they presented

themselves, or where they needed to adjust to

the winds of change. Second, they condensed the

guiding principles into three catchphrases I

fragrances; I my clients; and I to win

together that were used to convey the core ideas

of the divisions strategy to all employees.

Flavors division

The construction of a collective identity for this

division was very difficult, as several different

attempts to create a simplified version of the key

characteristics of the organisation were rejected

as too simplistic. Ultimately, participants built a

detailed miniature showing the three major

internal segments of the division, with a variety

of elements added to each section to symbolise

the differences in their components, personnel,

strengths, weaknesses, techniques, etc. Behind

this threefold external face of the organisation

participants built a narrow set of communication

channels to the very small support departments

overloaded with information requests. Thus, participants saw their organisation as a broad, flat,

diversified external surface dependent on insufficient internal support.

The simple guiding principles drafted by this

group focused on what they called the tubes,

which were those few, highly valuable links that

connected them to their clients. Their actions,

they stated, should be guided by the two ideas:

Build more tubes and Build the tubes right through

the organisation. Both of these simple guiding principles bear directly on the insight that success

lay in proliferating these tubes. In assessing their

own X6 strategic plan, they determined that it

simply reflected the complexity of their own

internal structure, rather than identifying ways

of being successful. Weve just underlined where

the bottlenecks are in our value creation, said one

participant, adding,

The whole thing [X6 plan] gets even more complicated

when you look at the various feedback links. In fact,

bad structures only get worse when you link them up.

The problem with all these links is that they dont tell

you how to act.

At the end of the workshop, the only Vice

President among the group, who reported directly

to the Division President, spontaneously left the

room and ran up two floors in the building

looking for his boss. In five minutes he was back,

accompanied by this individual, and by the

Corporate Vice President for Strategy for all of

ChemTech. He drew them over to representation

to explain to them what the group had built, and

to relate it to what they now saw as the inadequacies of the divisions strategic plan.

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 7

Crafting sense at ChemTech

In an e-mail received several weeks later from

the Vice President responsible for strategy, he said

that he had reviewed the new sense of strategic

purpose with both the top Corporate Strategist

and his divisional President with positive results.

This became clearer, two months later, when the

division announced a strategic reorganisation. Its

express purpose was to build more of the tube

relationships with clients throughout the organisation, and also make these relationships flexible

enough to permit adaptive action when client

needs shifted. The division, thus, had been shaken

out of their analysis paralysis, and were taking

purposeful steps to be an effective solutions

provider to their complex market.

Specialty Chemicals division

After an initial attempt to create a very orderly

depiction of the organisation merged with elements of its context, a discussion among participants in this group focused on several problematic

internal relationships. Returning to the model,

they converged on the image of a flat information

surface in which an interwoven network of relationships knitted together production, marketing

and planning, with an emphasis on the quality

of the links. The manager who oversaw the entire

engineering function was especially emphatic

about indicating blockages in the links between

people, insisting We have to show how it really is.

The final version showed that the Number 2 man

in the division was connected, it seemed, to everything and everyone. The Division President, by

contrast, noted that while he himself was an

active and mobile supervisory component on the

information surface, he wasnt really connected

to anything except the computerised data system

of the organisation.

The landscape in which this flat information

surface was located became populated by a very

wide variety of external elements, representing not

only competitors and joint ventures, production

sites and outsourced production sites, but also

several regulatory agencies and university research

alliances. The participants were especially interested in how the Vice President of Purchasing

showed distinctions among the several competitors, represented by pussy-cats, grumpy bear, and

devious snakes. I really like how the competitors

are shown as different species of animals, one of

his colleagues said; it clearly shows how and why

theyre different.

This group too was struck by the fact that

populating the Balanced Scorecard model had led

them to neglect several crucial strategic implications of their organisational setting. In the final

discussions, the idea surfaced that there were actually highly important effects for all the divisions of

ChemTech which could not be excluded from the

discussion of their own division as a result. The

simple guiding principle Understand impacts on

the whole group emerged. And, reflecting on their

organisational identity as a complex interpersonal

and informational network, they also stated Dont

depend on single individuals. Finally, in recognition

of the need to keep the external web of relationships they had with their industry intact, they

agreed to Maintain trusting relationships.

In closing the workshop, the Corporate Vice

President in charge of the division commented to

the group:

Im really glad I didnt send out the memo Ive been

working on about the state of the division. Ive got to

redo it completely in light of what weve now learned

about the way we all work together.

Another participant added, Its surprising that

when you work on seeing how you see yourself,

you dont have to put so much effort into wondering what the future will be. The person sitting

next to him nodded, and commented, When you

heed all the things surrounding you, the ideas

just seem to come. Hoping to frame subsequent

conversations with colleagues and subordinates

around the model they had just built, they carefully packed it away in large boxes in order to be

able to reconstruct it later on. During subsequent

meetings between this top management team and

their several dozen direct reports, this reconstructed model served as the basis for how the

entire strategic situation of the division was

discussed.

Exhibit 6 summarises what Imagination Lab

identified as the key insights and conclusions from

the three crafting sense workshops.

Sources

Brgi, P. and J. Roos, Images of strategy, European

Management Journal, vol. 21, no. 1, 2003, pp. 6978. Brgi,

P., C. Jacobs, and J. Roos, From metaphor to practice in

the crafting of strategy, Journal of Management Inquiry (forthcoming). Roos, J., B. Victor, and M. Statler, Playing seriously

with strategy, Long Range Planning, forthcoming, December

2004. Roos, J. Sporting strategic imagination, Sloan Management Review, Fall 2004, forthcoming.

ECS_04W.qxd 1/11/2004 10:58 Page 8

Crafting sense at ChemTech

Exhibit 6

Summary of workshop outcomes

Division

Key insight of workshop

Outcome and impact on strategic plan

Fragrances

We have a great process, but were

not prepared to respond to the

inevitable winds of change.

Use the strategic plan as a point of

reference, and leave room to adjust where

needed; cascade strategy with simple

ideas rather than numbers.

Flavors

Our plan and structure are simply

reflecting the markets complexity,

not creating distinctive value in it.

Supplement the strategic plan by identifying

and supporting key relationships in our

complex market, rather than trying to be all

things to all segments of it.

Specialty

Chemicals

Our role in the centre of corporation

means that we are intensely

interdependent with all parts of it.

Focus more on inter-divisional relationships

as a counterbalance to the Balanced

Scorecard approach.

You might also like

- Driverless Cars Will Be Great Complements to Mass TransportDocument3 pagesDriverless Cars Will Be Great Complements to Mass TransportAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Carrefour Document de ReferenceDocument296 pagesCarrefour Document de ReferenceAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Research Paradigms: Ontology'S, Epistemologies & Methods: Terry Anderson PHD SeminarDocument56 pagesResearch Paradigms: Ontology'S, Epistemologies & Methods: Terry Anderson PHD SeminarAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- What Is Big Data?Document7 pagesWhat Is Big Data?Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document12 pagesLecture 3Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Understanding Research Philosophies and ApproachesDocument22 pagesUnderstanding Research Philosophies and ApproachesAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- NUSTian Final July SeptDocument36 pagesNUSTian Final July SeptAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Boomerang Employee: Brendan Browne Is Vice President of Global Talent Acquisition at Linkedin Says, My CurrentDocument5 pagesBoomerang Employee: Brendan Browne Is Vice President of Global Talent Acquisition at Linkedin Says, My CurrentAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - 02Document36 pagesGroup 1 - 02Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Boomerang Employee: Brendan Browne Is Vice President of Global Talent Acquisition at Linkedin Says, My CurrentDocument5 pagesBoomerang Employee: Brendan Browne Is Vice President of Global Talent Acquisition at Linkedin Says, My CurrentAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Job AnalysisDocument11 pagesJob AnalysisAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Short - IsHRM Case Detailed Year by Year DvptsDocument9 pagesShort - IsHRM Case Detailed Year by Year DvptsAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Amisha Gupta Case QuestionsDocument1 pageAmisha Gupta Case QuestionsAdeel Khan0% (1)

- What Is Big Data?Document7 pagesWhat Is Big Data?Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Structure 4Document12 pagesStructure 4Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 Best FitDocument10 pagesLecture 3 Best FitAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Short - IsHRM Case Detailed Year by Year DvptsDocument9 pagesShort - IsHRM Case Detailed Year by Year DvptsAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - 01Document54 pagesGroup 1 - 01Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- 15 Poverty Social Safety NetsDocument13 pages15 Poverty Social Safety NetsAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Task 1 Week 1 - Emergent or Planned Change - AdeelDocument2 pagesTask 1 Week 1 - Emergent or Planned Change - AdeelAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Interpretivism in OrganizationsDocument42 pagesEvolution of Interpretivism in OrganizationsAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2011-2013 SBPDocument43 pagesAnnual Report 2011-2013 SBPAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Fatawa Credit CardsDocument24 pagesFatawa Credit CardsAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Thesis by StudentsDocument6 pagesThesis by StudentsGulalai KhanNo ratings yet

- L6 - MotivationDocument26 pagesL6 - MotivationAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Instruments For Meeting Budget DeficitDocument64 pagesInstruments For Meeting Budget DeficitAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- CH 2Document6 pagesCH 2Adeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Kurt Lewins ApproachDocument13 pagesKurt Lewins ApproachAdeel Khan100% (1)

- 15 Thompson and NabeelDocument40 pages15 Thompson and NabeelAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Project Team ManagementDocument20 pagesProject Team ManagementAdeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Science Curriculum PDFDocument107 pagesScience Curriculum PDFAneilRandyRamdialNo ratings yet

- Effective HR Training and Development StrategyDocument86 pagesEffective HR Training and Development StrategyKaran PalwankarNo ratings yet

- Case Study MISDocument12 pagesCase Study MISjayamani_bscNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management of Malaysian AirlineDocument7 pagesStrategic Management of Malaysian AirlineGeneisseNo ratings yet

- Information Technology Project Management: by Jack T. Marchewka Northern Illinois UniversityDocument35 pagesInformation Technology Project Management: by Jack T. Marchewka Northern Illinois Universityaepatil74No ratings yet

- Concept Paper TourismDocument19 pagesConcept Paper TourismFaxyl PodxNo ratings yet

- Session 4 - Beta GolfDocument21 pagesSession 4 - Beta GolfImranJameel100% (1)

- General Counsel Legal Strategy in Detroit MI Resume Stephen SerrainoDocument3 pagesGeneral Counsel Legal Strategy in Detroit MI Resume Stephen SerrainoStephenSerrainoNo ratings yet

- Smart Cities: Transforming The 21st Century City Via The Creative Use of Technology (ARUP)Document32 pagesSmart Cities: Transforming The 21st Century City Via The Creative Use of Technology (ARUP)NextGobNo ratings yet

- Hyatt Hotels Case Study Strategic AnalysisDocument9 pagesHyatt Hotels Case Study Strategic AnalysisShazrina SharukNo ratings yet

- Witt What Is Specific About Evolutionary EconomicsDocument29 pagesWitt What Is Specific About Evolutionary EconomicsJavier SolanoNo ratings yet

- Full Thesis in PDFDocument495 pagesFull Thesis in PDFrashmiamittal100% (1)

- Case Study GokongweiDocument9 pagesCase Study Gokongweiclearanne80% (5)

- Why Do Most Business Ecosystems Fail?: by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian SchüsslerDocument10 pagesWhy Do Most Business Ecosystems Fail?: by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian Schüsslerwang raymondNo ratings yet

- Innovation, Sustainable HRM and Customer SatisfactionDocument9 pagesInnovation, Sustainable HRM and Customer SatisfactionmonicaNo ratings yet

- Strategic PlanningDocument27 pagesStrategic PlanningDr. Pooja DubeyNo ratings yet

- Ajinomoto (Half)Document25 pagesAjinomoto (Half)Chris Chan Lek Lun67% (6)

- Netflix StrategyDocument3 pagesNetflix StrategyDownload100% (1)

- 12 - Speculative FictionDocument4 pages12 - Speculative Fictionapi-297725726No ratings yet

- Thanks To The Accenture Human Capital Development FrameworkDocument4 pagesThanks To The Accenture Human Capital Development FrameworkSony JenniNo ratings yet

- QualityDocument30 pagesQualityAdelina Burnescu50% (2)

- Transformational Leadership, Organizational Learning & Tech Drive SMADocument24 pagesTransformational Leadership, Organizational Learning & Tech Drive SMAdiahNo ratings yet

- Learning Vs Design SchoolDocument3 pagesLearning Vs Design SchoolRupashi GoyalNo ratings yet

- Corporate Affairs. Redefining The Role, Releasing The PotentialDocument11 pagesCorporate Affairs. Redefining The Role, Releasing The PotentialmetibookNo ratings yet

- Importance of IOCL's CRM and Loyalty ProgramsDocument8 pagesImportance of IOCL's CRM and Loyalty ProgramsMohit AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Business Strategy Course on Corporate Restructuring and M&ADocument2 pagesBusiness Strategy Course on Corporate Restructuring and M&AOrange NoidaNo ratings yet

- Safa Edited4Document17 pagesSafa Edited4Stoic_SpartanNo ratings yet

- Philippine Christian University Dasmariñas CampusDocument14 pagesPhilippine Christian University Dasmariñas CampusKrystalove JjungNo ratings yet

- Final Full Syllabus of ICAB (New Curriculum)Document96 pagesFinal Full Syllabus of ICAB (New Curriculum)Rakib AhmedNo ratings yet

- By Himanish Kar PurkayasthaDocument9 pagesBy Himanish Kar PurkayasthadoniaNo ratings yet