Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Victimization

Uploaded by

Zulfqar AhmadCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Victimization

Uploaded by

Zulfqar AhmadCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Victimization & Drama in News

Victimization and Drama in News Coverage of Kidnapped Victims

Paper submitted for presentation consideration at the News Division,

Broadcast Education Assoication, Las Vegas, April 9-13, 2011

Victimization & Drama in News

Abstract

The so-called Missing White Women Syndrome in the media was largely a popular

belief that has not been systematically investigated. This study used victimization

theories in narratives to guide an investigation into coverage of the AMBER Alert

victims. Results indicated that the story behind the syndrome was multilayered. Findings

also helped inform discussions on its possible conceptualization.

Key words: Damsel in Distress; AMBER Alert; Narratives; Victimization; News

Sensationalism.

Victimization & Drama in News

Victimization and Drama in News Coverage of Kidnapped Victims

When a kidnapping occurs, it evokes feelings of revulsion, fear, indignation,

incredulity and discomfiture - few felonies stir up such a gamut of emotions, or command

our attention as completely as the abduction of a child for perverse ends. Televisual and

print media are saturated with stories of such crimes. However, as Clark (2008)

poignantly opines: Kidnapping sells, but not every kidnapping is equal." Sensational,

emotionally laden accounts of victimization in journalism have been demonstrated to

increase emotional response (Aust & Zillmann, 1996). Stories that are laden with

sensationalism, graphic detail, and dramatic content appear prominently. This

perceptible emphasis suggests that such news items captivate the attention of viewers and

offer strategic benefits in the competition for audiences among media outlets

Consequently, the skeptical assertion that mass media organizations are predisposed

towards selective coverage of sensational and salacious stories has been advanced by

scholarly and popular critics (Clark, 2008).

A frequent criticism has been directed toward the perception of asymmetry in

media coverage of kidnapping victims based upon their race, sex, and class. The most

prominent description of this phenomenon has been dubbed the Missing White Woman

Syndrome in popular culture. Abductions involving young, attractive white females of

reasonable socio-economic means receive an inordinately greater amount of news media

coverage compared with an abduction involving a subject of contrasting race, ethnicity,

sex, pulchritude, age, or social status. Anecdotal evidence abound: Chandra Levy,

Elizabeth Smart, Laci Peterson and Natalee Holloway readily come to mind for even the

most aloof consumers of mass media in the United States. Foreman (2006) argues that

Victimization & Drama in News

Missing White Woman Syndrome is characterized by a basal and cynical formulation:

Pretty, white damsels in distress draw viewers; missing women who are black, Latino,

Asian, old, fat, or ugly do not. Evidently, the phenomenon finds indemnity, once again,

in the contradiction between the perceived normative goal of editorial objectivity and the

strategic, fiscal imperatives of the media industry: increased viewership. In order to

capture and retain viewer attention, media outlets pander to the entertainment-orientation

of viewers, and disproportionately focus on the abduction and victimization of children

and adolescents and on white, middle class victims.

Despite these criticisms, no systematic study has been conducted to look into the

perceived imbalance of media coverage of victims of contrasting races, gender and age.

This exploratory study attempts to address this deficit. The importance of such an

endeavor is apparent. No reasonable person should come to any conclusion based on

anecdotal sensationalism, rather than verifiable statistical data or rational argument.

Unfortunately, haphazard, sensational accounts often guide political opportunists and

"moral entrepreneurs" in the formation of legislation and the mobilization of public

outrage over relatively rare instances of violent and/or sexual crimes (Fritz and Altheide,

1987).

It is the goal of this investigation to assess if the news media exhibits skewed

coverage of missing victims in terms of race, gender and age. This paper tries to

accomplish three objectives: empirically investigates the Missing White Woman

Syndrome, explicates theoretical rationales for the phenomenon, and identify dramatic

narrative elements that may contribute to such a perception. In this process, narrative

structures and theories are explored. The research also considers insight from Greek

Victimization & Drama in News

thinkers in conceptualizing dramatic narrative elements to analyze tales of distressed

kidnapped victims.

Literature Review

Victimization and Its Social Significance

News media reporting often focuses on the stories and personalities of victims as

dramatic elements that generate or maintain salience of the story (Chermak, 1995).

Discussion of victims has also been a consistent element of social problems research

because problems, by definition, involve some variety of injury to some variety of victim.

According to Best (1997), the rhetoric of victims rights paralleled the rhetoric of the

Civil Rights Movement. By the 1980s, victimization had become fashionable, the

therapeutic and self-help industries exploded in popularity, and victim advocacy

established itself as an industry. At the conceptual root of such broad socio-cultural

developments are two aspects of the ideology of victimization : the relationship

between the perpetrator and victim is unambiguous, and that claims regarding

victimization are to be respected, left unquestioned (Best, 1997, pp. 10-13).

If victims in general have been en vogue, children as victims have been especially

salient. For example, in the 1980s the missing children problem received a large amount

of political and mass media attention (Best, 1997, pp. 102-104). In many cases, horror

stories about child victims often serve to typify social problems in general (Johnson,

1995). Over time, sociologists have observed the persistence of child victims and their

salience for news events concerning many social problems. Similarly, children have

figured prominently as victims in crime myths because their perceived innocence plays

into their role as ideal victims (Kappeler & Potter, 2005).

Victimization & Drama in News

Tracing the origins of child victimization coverage in crime reporting, Freedman

(1987) compiled considerable evidence for the position that, by the 1930's, public outrage

over the broadly defined "sexual psychopath" was a byproduct of the redefinition of

sexual normality. Victorian concepts of male sexual agency, female purity and female

sexual passivity gave way to Freudian interpretations that recognized the existence of

overt and active female sexuality. This led an emphasis on children as potential victims

of unchecked masculine lust, and to vocalization of the need for legislation of sexual

"normalcy" by mass media, politicians, and citizen's groups. Children took on the role of

Edenic symbols of innocence and purity before the Fall, the transition from infancy to

adulthood acting as microcosmic reenactment of God's first condemnation of humanity's

disobedience (Kincaid, 1992, 71-75). Pre-pubescent children, like Adam and Eve, are

without shame, without knowledge of good and evil, and therefore vulnerable. Such

attributes become requisite for innocence and purity to exist, and thus children are to be

cloistered and diligently protected from those that would seek to corrupt them

prematurely (Kincaid, 1992, 71-75).

Moeller's (2002) formulation of the "hierarchy of innocence," corresponds readily

with such an interpretation. Analyzing mass media coverage of international conflict and

crisis, Moeller observed prioritization of victim status, focusing, in descending order,

upon "[...]infants, children under 12, pregnant women, teenage girls, elderly women, all

other women, teenage boys, and all other men." (Moeller, 2002, 49). Media outlets seek

to portray the brutality of a conflict by emphasizing civilian casualties, particularly

children and women Marketing consultants for international aid organizations implicitly

use this hierarchy in selecting poster children for a famine relief program (Moeller,

Victimization & Drama in News

2002). The press practice of linguistically de-gendering child abuse victims (e.g. use of

"child", "infant" or "it" as opposed to "boy" or "she") coincides with a desexualized

interpretation of childhood that further illustrates the association of innocence with youth

(Goddard and Saunders, 2000). Although dominant Western conceptions of innocence

and good stem from an absence of worldly corruption, and media producers may

understand innocence as a function of vulnerability toward physical or moral harm, both

interpretations are commonly employed in the development of dramatic narrative and the

determination of character archetypes, specifically "Princess" characters, or "Damsels in

Distress," and the villains and beasts that would do them harm (Douglas, 1995: 293-294).

Victimization and Dramatis Personae

In his systematic meta-analysis of formal features of Russian folktales, Propp

(1968) proposed that character attributes, setting, and specific actions exhibit seemingly

limitless variety, but that the fundamental dramatis personae can be distilled into seven

roles defined by their narrative function. The princess --"one who is sought after"--is

placed in this typology with her father, as the two characters often have interchangeable

functions: the princess may charge the hero with a quest to win her hand, or, having been

abducted, the father may compel the hero to seek the princess. These are variations of the

same functional outcome; the sought-after princess and the ability of her father to

ennoble the hero serve as the dual motivating objects for such a tale (Propp, 1968: 7991).

Rhrich's (2008/2002) analysis of female personages in Western European fairy

tales argued against a homogenized interpretation of heroines, although two key

attributes--passivity and pubescence--are conspicuously familiar aspects of female

Victimization & Drama in News

characters in modern Western folktale derivations, such as animated Disney

features. Cinderella, Snow White, and Sleeping Beauty, all girls on the precipice of

adulthood, all physically beautiful, exhibit a naivete to wickedness, and a pious passivity

in the face of cruel oppression. Damsels in distress often radiate an archetypal innocence

that beckons heroic salvation. The popularity of these dramatic motifs inspire a continual

succession of derivative work. In a survey of modern children's literature, for example,

White (1986) found that narratives focused on rescue, abduction, and captivity featured

no male victims and no female saviors. A systematic content analysis of depictions of

child mistreatment by adult characters in Disney animated films has demonstrated not

only exceptionally high incidences, when compared to criminological statistics, of

emotional and physical abuse, neglect, captivity, inappropriate affectionate advances, and

threats of violence, but also an unrealistically optimistic view of successful rescue, or

familial reunification (Hubka, Hovdestad, & Tonmyr, 2009). In crafting dramatic

narrative, this thematic formula--the vulnerable and innocent protagonist's survival in

spite of hardship, villainy, and threat of corruption--elicits sympathy for suffering

endured and expectation of positive resolution (Hubka, Hovdestad & Tonmyr, 2009). Of

course, it is almost always the physical beauty of the princess figure that initially inspires

the dramatic conflict of the plot, whether due to the jealousy or avarice of the wicked

stepmother, or out of the lust of a smitten beast, a troll, or a criminal (Do Rozario, 2004;

Rhrich 2008/2002). This beauty transcends superficial evaluation; it signifies the

acceptance of and adherence to the status quo (Do Rozario, 2004). Taken in combination

with an assumed de facto youthful innocence and therefore moral good, the beautiful

princess symbolically inspires confidence in the chain-of-being.

Victimization & Drama in News

Victimization and Dramatic Elements

The prototypic American convergence of news and dramatic entertainment is

found in the classic account of the popular news show 20/20, which fared disastrously

when first aired in 1978. Facing cancellation, the shows format was expeditiously

changed from hard news to more entertainment-oriented spectacle, upon the advice of its

research team. Its three-decade survival serves as an irrefutable testament to the

inexorable value of combining dramatic elements and plots with news reporting, and its

successful formula has been heavily adopted by news organizations Media outlets

employ a multitude of devices to enhance the dramatic value of a news item. Frequent

techniques include the exaggeration of conflicting elements to present stark dramatic

contrasts, explication of misfortune or victimhood, and the establishment of clear,

adversarial relationships. Dramatic devices may also include an emphasis on positive

and negative human interactions, such as friendliness and hostility, which may arouse

feelings of empathy, joy, grief, fear, and anger. Tailoring a storys attributes in this way

elicits audience empathy, and coaxes viewers into identifying with the victim or victims

loved ones. (Miller, 2006 p300).

Although arguably constituting an abrogation of the purpose of the news media,

the inclusion of dramatic elements and plots evidently represents the archetypal approach

to news reporting. The underlying rationale for this modus operandi is that news is one

of many genres of storytelling that enlighten and entertain viewers, listeners and readers

(Grabe & Zhou, 2003). Inherent in this exposition is the assumption that news reporting

devoid of dramatic elements can be potentially perceived as bland, dull, and therefore

10

Victimization & Drama in News

alienating to audiences. Considering the exigencies of market-driven mass media, there

is, decidedly, intrinsic value in the convergence of journalism and fiscal imperatives

(McManus, 1994); alienating viewers would be largely inexpedient and counter-intuitive.

To this end, the need for drama appears to be both an inescapable and de rigueur part of

news stories. The veracity in this assertion is perhaps best confirmed in the legendary

memo executive producer Reuven Frank of NBC News sent to his staff which charged,

[e]very news story should, without any sacrifice of probity or responsibility,

display the attributes of fiction, of drama. It should have structure and conflict,

problem and denouement, rising action and falling action, a beginning, a middle,

and an end. These are not only the essentials of drama: they are the essentials of

narrative (Epstein, 1973, pp. 4-5).

This almost theatrical exegesis finds fervid support in the literature. While

Postman (1988) categorically declared that news was theatre, other scholars asserted that

news reporting in the media was more an execution of dramatic effects than a legitimate

representation of the goings on in the world (Tuchman, 1978; Graber, 1994). In an

apparent censure on the populist view, German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer,

vindicated the media for its insouciant propensity to employ dramatic devices in news

coverage: Exaggeration of every kind is as essential to journalism as it is to dramatic art,

for the object of journalism is to make events go as far as possible (Schopenhauer,

2008).

The insights of Greek thinkers-who practically invented drama in storytelling

can also be used to explain the lineage and logic of news drama in contemporary

kidnapping coverage. According to Aristotle, the success of drama consists of three

componentslogos, ethos and pathos. The logos strategy is to convince audience

members by responding to a particular situation in a partisan way. The rhetorical

guidelines for a partisan description are vividness and clarity, which in kidnapping stories

11

Victimization & Drama in News

are best exemplified by innocence, vulnerability, and depravity of the perpetrators. The

ethos strategy is based on efforts to establish the reliability and credibility of the speaker,

who is then able to establish the moral integrity and factual authority of the main

argument. In this case, the salvation of the damsel in distress speaks directly to the moral

force when the villain is brought to justice. Finally, the pathos strategy is designed

specifically to arouse strong emotions in the audience (Aristotle, 1954). Kidnapping

stories have plenty of such fodder: violence, sex and contrast, conflicts and dilemmas are

staples of such tales.

. Although a highly compelling event, such as a kidnapping, automatically

contains, for example, the dramatic element of emotion, the event itself is not necessarily

responsible for the creation of drama. The methods by which news is packaged, and the

narrative techniques employed in its presentation, serve a fundamental role. Producers

frequently arrange information scenically to construct a plot, elicit or sustain a mood, or

support a narrative perspective. (Berner, 1988; Grabe, Zhou, & Barnett, 2001; Grabe,

Zhou, Lang, & Bolls, 2000). As Rosenthal (1999) argued, the use of these techniques is

to particularize an event around a story line with characters. The dramatic features help

render an intimate depiction of the main figures, whose lives and experiences are

portrayed with intensity and focus. Such integration of novel information with familiar

narrative devices facilitates empathy. Viewers are not merely invited into an exposition

but also to view a drama of highly imaginative potency.

Just as entertainment industry firms commonly repackage archetypes to generate

successful film franchises, modern news agencies, in their role as storytellers, employ

traditional dramatis personae and narrative structures and plot elements to generate

appealing and compelling information commodities (Barkin, 1984).

Media construction of narratives frequently avoids nuance and moral ambiguity

(Barkin, 1984). Youth, race, and gender can be understood to independently signify

12

Victimization & Drama in News

vulnerability, innocence, and desirability, and certain combinations of these factors can

intensify the conveyance of such attributes, heightening a story's dramatic conflict

(Moeller, 2002). Conflict is distilled into elemental positions of good and evil, or of

innocence and depravity. Such representations further serve to strengthen the moral

stance of "objective" journalism, and discourage rational criticism or dissent. (Kincaid,

1992; Moeller, 2002). Furthermore, chaotic and mundane phenomena from everyday

reality, grafted onto archetypal narrative frames that are best suited for communicating

with clear causality--extraordinary deeds carried out by fantastic characters, facilitate

sensationalism and conflate exceptions for rules (Barkin, 1984; Aust & Zillman, 1984;

Chermak, 1995). However, considering the dominant normative conceptions of an

atrocity such as kidnapping the abduction of a defenseless, vulnerable child - the

substantive content of the crime may ostensibly be deemed adequate for providing the

nexus for a media maelstrom; narrative or archetypal embellishments may prove entirely

unnecessary. In order to determine the manner in which actual victims and events are (or

are not) represented by mass media organizations, an analysis of news reports related to

AMBER Alert child abduction and victimization cases was conducted.

The AMBER Alert

The disturbing case of Amber Hagerman, who was abducted and murdered in

Texas in 1996, served as the impetus for the AMBER (America's Missing: Broadcast

Emergency Response) Alert program. On January 13, 1996, Amber Hagerman was

abducted while riding her bicycle and brutally murdered. The AMBER Alert network

was created in response to this tragic event. AMBER Alerts are essentially emergency

messages that are broadcast by law enforcement agencies when a child is abducted and is

13

Victimization & Drama in News

facing menacing danger. Information such as physical description, the abductors vehicle,

and other salient facts are furnished to the public to facilitate the safe return of the

abductee. This early warning system was the result of collaboration between Dallas-Fort

Worth broadcasters and local police after Amber Hagermans tragic death. The Justice

Department defines the AMBER Alert Program as

a voluntary partnership between law-enforcement agencies, broadcasters,

transportation agencies, and the wireless industry, to activate an urgent bulletin in

the most serious child-abduction cases. The goal of an AMBER Alert is to

instantly galvanize the entire community to assist in the search for and the safe

recovery of the child. (USDJ, 2010)

According to the Department of Justice, the AMBER Alert program has been

responsible for helping with safe recovery of 495 children since its inception.

Additionally, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin

Islands have now instituted AMBER Alert plans. These statistics bear testimony to the

ostensible success of the program, and provides tacit evidence that the public has

favorably embraced it throughout the United States and its regions.

The AMBER Alert program provides an ideal forum to look into how stories

involving AMBER victims were portrayed in the news media. Specifically, this paper

looked at three aspects of such coverage by asking the following three research questions:

1.

Is coverage disproportionately associated with AMBER victims of belonging

to specific race, sex, or age categories, as some critics have claimed?

2. The literature indicates that the potential intensity of dramatic content is much

greater in cases where strangers, rather than family members, perpetrate

abductions, or if physical or psychological harm befalls the victim. Are

14

Victimization & Drama in News

variables such as the perpetrators relationship to the victim or the crimes

degree of atrocity correlated to the amount of coverage the story receives?

3. Finally, the paper also looks at the narrative treatments of these stories and

map them against the predictors of race, gender and age to determine if there

are any differences in their narrative potential. In other words, do the stories

differ in narrative treatments when the victim is White, female, or young, in

contrast to a victim who is Black, male, or more mature?

Method

To answer research questions, a content analysis was conducted. The data for this

study are derived from a census of the 136 AMBER Alerts issued from July 2005 to

March 2008 and listed on the Americas Most Wanted: Missing Children website. The

website and affiliate television program are dedicated to fighting on behalf of children

and all crime victims (AMW Website, 2010). The site and television program claim to

have helped to take down over 1,050 dangerous fugitives and bring home more than 50

missing children in the past 22 years (AMW Website, 2010). The website has a

comprehensive list of children for which recent AMBER Alerts have been issued. The

website also has a searchable, by year, archive of children for which AMBER Alerts have

been issued. While this archive is not exhaustive it includes all interstate issued AMBER

Alerts and provides descriptions of the children, case details, descriptions of potential

perpetrators, as well status of the investigation. This site was cross-referenced and

compared to the Code Amber Website used in previous studies (Griffin, et. al, 2007). The

AMW site was found to be more comprehensive and complete, particularly for more

recent AMBER Alerts as the Code Amber Website is no longer updated regularly. All

15

Victimization & Drama in News

available listed AMBER Alerts (136) for the time span of July 2005 to March 2008 were

analyzed.

The list of names provided from the AMW website were then cross referenced to

archived stories featuring the childs name in the New York Times and USA Today

newspapers, as well as in broadcast transcript archives from CNN and Foxnews websites.

These news organizations were chosen for their viewership, devotion to comprehensive

news coverage, as well as their stewardship of the news agenda and their use in an

exhaustive list of research content analyses of news coverage.

Coders then analyzed each news story or broadcast transcript on three sets of

factors. The first set of variables included demographics: gender, race, socio-economic

status and age of the victim (age was reported as a raw number and categorized in four

groups: 0-5 yr olds, 6-10 yr olds, 11-15 yr olds, 16+). The second set of variables

assessed variables related to the alert: time missing (in days), relationship of victim to

suspected perpetrator (stranger abduction, parental abduction, abduction by acquaintance

of the victim, abduction by friend of the family, other/runaway), whether or not the

victim was described as physically or psychologically harmed, and number of suspected

perpetrators, race and age of perpetrator, and whether or not the perpetrator was a

previously convicted sex offender. The third set of variables dealt with narrative elements

of the stories. Coders analyzed each story for the following dramatic elements: Conflict

(presence of stated dispute or altercation), Contrast (story is contrasted to another similar

event or past story), Dilemma (law enforcement or parents face crisis outside of the

abduction that hinders efforts of investigation), Empathy (expressed empathy to family of

victim or child abducted), Violence (physical abuse toward the child or others directly

16

Victimization & Drama in News

related to the case, including law enforcement), Sex (sexual acts or potential sexual acts

perpetrated against the child), Innocence (of the victim, as in lack of deserving

mistreatment- this category does not relate to guilt or innocence of potential perpetrators),

Vulnerability (of child, of children of certain ages, races, or socio-economic classes), Evil

(demonizing of perpetrator), and Lurid details (graphic descriptions of acts or potential

acts committed against the child by perpetrator(s)).

Several sessions of coder training were conducted and the two primarily coders

conferred often to compare notes before coding separately. Overall intercoder reliability

for content analyses of news coverage using Holstis formula was .95. Overall intercoder

reliability for dramatic elements using Holstis formula was .91.

Results

The first research question asked if disproportionate coverage was related to the

AMBER victims gender, age, or race.

In terms of gender, of the total 136 cases examined, 91 (66.9%) were female and

45 (33.1%) were male. The study showed no significant differences in amount of

coverage between males and females (t (134)= -.116, p=.908). The mean number of

stories reported for each child based on gender (m=3.28 stories for males, m= 3.51 stories

for females) was not statistically significant.

The study found significant differences in the coverage of victims based upon

race. (F(3, 132)=3.05, p=.03). An ANOVA using a Bonferoni post hoc procedure found

that white children were featured in significantly more stories overall than Hispanic

children (m=6.029 for white children, m=.2703 for Hispanic children, p=.049). Hispanics

received the lowest mean number of reported stories of any group (n= 37, m=.27)

17

Victimization & Drama in News

compared to Whites (n=69, m= 6.02), and blacks (n= 28, m=1.03) (Asians were omitted

from the analysis because of a low sample size, n=2).

No significant differences in amount of coverage between categories of age (F(3,

132)= .630, p=.59). The mean number of stories reported for each child based on age

categories (m= 3.29 (n= 67) for ages 0-5, m=5.44 (n=27) for ages 6-10, m=3.34 (n=26)

for ages 11-15, m= .8125 (n=16) for ages 16 and over) were not significantly different.

The second research question asked if other variables involving the AMBER

victim might correlate with amount of coverage. These other variables included the

temporal length of abduction, the relationship of the victim to the suspected

perpetrator(s), whether the suspect was a previously convicted sex offender, and if the

child was physically or psychologically harmed.

The study found a significant positive correlation with amount of time missing

and number or stories (r(134) = .249, p=.003). Children missing longer than 5 days

(n=35, m=8.48) had the most news stories followed by, children missing 3-4 days (n=28,

m=2.35), children missing 1-2 days (n=43, m=1.8), and less than 24 hours missing (n=30,

m=.9).

The study found significant differences between the number of news stories

reported for Familiar abductions versus Unfamiliar abductions. Of the 136 cases, 46 were

Non--Family/Friend (m=7.82) and 90 were Family/Friend abductions (m=1.07). The

frequency of stories was significantly greater for cases involving Unfamiliar perpetrators

(t (134)= 3.58, p=.01).

The study found significant differences (F(2, 133)= 18.81, p=.001) between cases

in which suspected perpetrators had prior convictions for sexual offences (n=5, m=15.8)

and cases in which suspects had no prior record of sexual offences (n=111, m=1.10), or in

which suspect identity was ambiguous (n=20, m=13.94 A Bonferoni post hoc procedure

found that cases in which suspects had prior convictions of sexual offences, and cases in

18

Victimization & Drama in News

which suspects were unidentified, had significantly more stories than those in which

suspects had no previous sexual offence record.

The study found significant differences (F(2, 133)= 5.24, p=.006) in number of

total stories for when the victim was physically harmed (n=28, m=8.39), when the victim

was not physically harmed (n=87, m=1.36), and the uncertainty about whether the victim

was harmed or not (n=21, m= 5.42). A Bonferoni post hoc procedure found that when the

victim was physically harmed there were significantly more stories than when the victim

was not harmed physically.

The study found significant differences (F(2, 133)= 5.01, p=.008) in number of

total stories for when the victim was psychologically harmed (n=24, m=8.66), when the

victim was not psychologically harmed (n=75, m=1.17), and the uncertainty about

whether the victim was harmed or not (n= 37, m= 4.64). A Bonferoni post hoc procedure

found that when the victim was psychologically harmed there were significantly more

stories than when the victim was not harmed psychologically.

The third research question asked if the narrative treatments of news stories were

correlated with gender, race, and age.

For gender, the study found no significant differences between narrative

treatments and gender in any of the narrative categories (see Table 1).

[Insert Table 1 about here]

In terms of race, the study found significant differences in six of the ten narrative

elements, including conflict, dilemma, empathy, violence, innocence and vulnerability.

The categories that did not show statistical significance were contrast, sex, evil and lurid

detail (see Table 2). Bonferoni post hoc analyses revealed that the differences existed

between stories for missing Whites and Hispanics. No differences were found between

Whites and Blacks, nor Blacks and Hispanics.

19

Victimization & Drama in News

[Insert Table 2 about here]

In terms of age, the study found significant differences in eight of the ten

narrative elements, including conflict, empathy, violence, sex, innocence, vulnerability,

evil and lurid detail. The categories that did not show statistical significance were

contrast, and dilemma (see Table 3). Bonferoni post hoc analyses revealed that the

differences existed between stories for missing children 0-5 years of age and 6-10 years

of age. No differences were found among other age groups.

[Insert Table 3 about here]

Because many narrative categories were significant for both race and age, the two

variables were further analyzed to see if there were any interaction effects. Results

indicated that within every age category, White children received more coverage in every

narrative category (Due to the small sample size (n=2), Asians were omitted from

analysis).

[Insert Table 4 about here]

Conclusions and Discussions

Popular and scholarly critics have reacted to the mainstream medias seemingly

disproportionate attention to the plights of abduction victims of contrasting genders, ages,

and races by offering the diagnosis of Missing White Women Syndrome. This

phenomenon is frequently lamented but previously lacked systematic investigation. The

present study analyzed two sizable bodies of datacriminological data related to the

20

Victimization & Drama in News

national-level abduction of minors in the United States, and the coverage of each case by

major print and televisual news organizationsand found empirical evidence for several

rational arguments.

There are some very interesting findings. By and large, gender alone was not a

significant predictor of the amount of coverage for abductions. Missing males and

females were likely to receive the same amount of media attention. Age also did not

make a difference. Similarly, the age of the victim was insignificant; young missing

children and adolescent teenages received roughly equal time. Race mattered, to an

extent. Whites received more coverage than Hispanics. Yet, there was no observed

disparity between coverage of cases involving White and Black victims, nor Black and

Hispanic victims.

The length of time that a child was missing was found to be a fundamental factor

in predicting the amount of press coverage a case received, and this exhibited a rather

positive linear relationship. Furthermore, if the perpetrator was a non-family member,

the amount of stories increased. If the villain was a previous sex offender, coverage

skyrocketed. Similarly, coverage intensified when the victim was known to be physically

and/or psychologically harmed, but remained missing. The mediated presentation of

such cases was observed to have commonality with traditional tales of abduction-bystranger and narratives based upon the contrast of the diametrically-opposed concepts

such as of innocence and depravity, and, by extension, good and evil. Such cases

contained elements with high dramatic potential; their particular details inherently made

for riveting and evocative news fodder, and therefore the motivations of media producers

for focusing attentively on them seem rather intuitive. The narrative plots were clear:

21

Victimization & Drama in News

innocence was threatened by corruption and rescue was an undebatable moral imperative.

being corrupted and needed rescue. There was no ambiguity and no nuance that might

obscure the storyline: the vulnerable protagonists fate was uncertain, but, without doubt

survival required, if not heroic deeds, at least heroic efforts.

What, then, is to be made of the Damsel in Distress? Clearly the data indicated

that it did not matter whether the victim was a damsel or a lad, stripling or mademoiselle.

Merely distress was enough of a selling point to generate and maintain the salience of a

news event. The successful defeat and destruction of the causal agent of this distressa

criminal, a beast, or a trollwas required in order to preserve innocence and restore

harmony. Distress, functioning as an essential ingredient of the tragedy, automatically

established the threatened protagonist and menacing antagonist (regardless of whether the

latters identity was known), and thus indicated a simple plotline, simultaneously

sensational and uncontroversial, that carried high potential for viewer salience, prolonged

attention, and advertising revenue. If distress is given priority over the damsel, how

can the condemnation of Missing White Woman Syndrome be understood? Of all the

AMBER Alert victims, one may note that there were twice as many females (66.9%)

missing than males (33.1%). Among all missing females, 71% of them were Whites, a

percentage which is not significantly divergent from general U.S. population

demographics Girls were simply abducted more than were boys, which may contribute to

an impression that coverage for missing girls is disproportionate.

However, closer examination of the narrative structures and dramatic elements

employed to convey stories involving young, White victims , found them to significantly

differ from the manner in which abductions of older children, or Black or Hispanic

22

Victimization & Drama in News

victims, were portrayed Overall, the plight of young (ages 0-10), White victims was

communicated to audiences with a much higher incidence of several dramatic elements,

notably: conflict, innocence, vulnerability, evil, and lurid details

Sample sizes for some categories were, unfortunately, not large enough for many

statistical operations to be performed on the data. However, it seems intuitive that

dramatic elements and narrative treatments would become more and more prevalent

during continued coverage for any particular caseas new details come to light, or as

new perspectives on the incident are explored (e.g. the ordeal of the victims family,

thoughts of the suspects co-workers, or how one abduction may parallel a previous highprofile abduction). Children abducted by strangers for more than 48 hours were

numerically more likely to be White, whereas familiar abduction was more evenly

distributed along racial/ethnic categories. A prolonged abduction by a stranger allows for

media outlets to orchestrate a clever parade of narrative treatments. Such cases were

richer in dramatic potential than stories in which such embellishments were not feasible.

Considering that, numerically, these incidents involved young, White victims and that

females were more frequently victimized the sensational stories of these young White

victims in the media maelstrom, over time, might be a contributing factor to the

misconceived notion of Missing White Women Syndrome.

It is the belief of the researchers that the reality behind Missing White Woman

Syndrome is considerably more complex and nuanced than simply disproportionate

attention to victimization of specific ethnic or gender groups. Instead, it appears that

news organizations devote significant resources, and presumably attract the attention of

audiences, to the prolongation of morally unambiguous dramatic tension. This

23

Victimization & Drama in News

distinction is significant because the intense focus on sensational, exceedingly rare,

horrific criminal acts, coupled with the encouragement of audience diligence over a

considerable length of time creates a feedback loop of heightened alert. Regardless of the

victims age, ethnicity, or sex, it seems that such journalistic practices exploit victims and

audiences alike, while neglecting its normative professional goals.

Several limitations are present in the current investigation. Most significantly, the

sample population of abduction cases that led to the issuance of nation-wide AMBER

Alerts should not be assumed to necessarily represent the totality of child abduction

crimes in the United States. AMBER Alert policies differ from state to state, and the

criteria for nationwide Alerts would exclude cases in which the whereabouts of missing

children were localized. Similarly, AMBER Alert cases may not represent the totality of

missing childrens or missing persons coverage in mainstream news outlets. For

example, the highly-publicized case of missing high-school student Natalee Holloway

involved no issuance of an AMBER Alert. At the time of this writing, no publicly

available statistical data for child abduction exists in the U.S., and record-keeping

practices and access policies vary between states.

Future research may be able to further investigate the representation of abduction

victims in mass media by analyzing, for example, use of images, video, and production

elements in the coverage of one category of victim versus another. The use of televisual

journalism to facilitate passive participation in the televised searches for missing

children, or to shape attitudes toward certain categories of suspects may be of interest to

scholars of political communication, persuasion, or social psychology.

24

Victimization & Drama in News

References

Americas Most Wanted: Missing Children, Active and Issued AMBER Alerts (2010),

retrieved March 25th, 2010 from http://www.amw.com/missing_children/amberalerts.cfm.

Aristotle. (1954). Rhetoric. (W. R. Roberts., Trans. ). New York, NY: Modern Library.

Aust, C. F., & Zillmann, D. (1996). Effects of victim exemplification in television news

on viewer perception of social issues. Journalism and Media Communication

Quarterly, 73 (4), 787-803.

Barkin, S. M. (1984). The journalist as storyteller: an interdisciplinary perspective.

American Journalism, 1 (2). 27-34.

Berner, R. T. (1988). Writing literary features. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Best, J. (1997). Victimization and the victim industry, Society, 34 (4), 9-17.

Chermak, S. M. (1995). Victims in the News: Crime and the American News Media.

Boulder: Westview Press.

Clark, R. P. (2008). Missing people face disparity in media coverage. Retrieved March

29, 2010 from http://rotofoundation.com/bulletinboard.aspx

Do Rozario, R. C. (2004). The princess and the magic kingdom: beyond nostalgia, the

function of the Disney princess. Women's Studies in Mass Communication, 27

(1), 34-59.

Douglas, S. J. (1995). Where the girls are: growing up female with the mass media.

New York: Three Rivers Press. 293-294.

25

Victimization & Drama in News

Epstein, J. E. (1974). News from nowhere: television and the news. New York: Random

House.

Foreman, T. (2006). Diagnosing missing white woman syndrome. Retrieved March 29,

2010 from

http://www.cnn.com/CNN/Programs/anderson.cooper.360/blog/2006/03/diagnosi

ng-missing-white-woman.html

Freedman, E. B. (1987). "Uncontrolled desires": The response to the sexual psychopath,

1920-1960. The Journal of American History, 74 (1), 83-106.

Fritz, N. J. and Altheide, D. L. (1987). The mass media and the social construction of the

missing children problem. The Sociological Quarterly, 28 (4), 473-492.

Goddard, C. and Saunders, B. J. (2000). The gender neglect and textual abuse of children

in the print media. Child Abuse Review, 9 (1), 37-48.

Grabe, M. E., & Zhou, S. (2003). News as Aristotelian drama: The case of 60 Minutes.

Mass Communication & Society, 6(3), 313-336.

Grabe, M. E, Zhou, S, & Barnett, B. (2001) Explicating sensationalism in television

news: content and the bells and whistles of form. Journal of Broadcasting &

Electronic Media, 45 (4), 635-655.

Grabe, M.E., Zhou, S., Lang, A. & Bolls, P.D. (2000). Packaging television news: The

effects of tabloid on information processing and evaluative responses. Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44, 581-598.

26

Victimization & Drama in News

Graber, D. A. (1994). The infotainment quotient in routine television news: a directors

perspective. Discourse in Society, (5:4), 483-808.

Griffin, T., Miller, M. K., Hoppe, J., Rebideaux, A., & Hammack, R. (2007). A

Preliminary Examination of AMBER Alert's Effects. Criminal Justice Policy

Review, Dec 2007; vol. 18: pp. 378-394

Hubka, D., Hovdestad, W., and Tonmyr, L. (2009). Child maltreatment in Disney

animated feature films: 1937-2006. The Social Science Journal, 46, 427-441.

Johnson, J. M. (1995). Horror stories and the construction of child abuse. In J. Best (Ed.),

Images of issues: Typifying contemporary social problems. Hawthorne, NY:

Aldine De Gruyter.

Kappeler, V. E., & Potter, G. W. (2005). The mythology of crime and criminal justice

(4th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland.

Kincaid, J. R. (1992). Child-loving: The Erotic Child and Victorian Culture. New York:

Routledge.

McManus, J. (1994). Market-driven journalism: let the citizen beware? Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Miller, M. K. and Clinkinbeard, S. S. (2006). Improving the AMBER alert system:

psychology research and policy recommendations. Law and Psychology Review,

30, 1-21.

Moeller, S. D. (2002). A hierarchy of innocence: The media's use of children in the

telling of international news. The Havard International Journal of Press/Politics,

7. 36-56.

27

Victimization & Drama in News

Postman, N. (1988). Conscientious objections: stirring up trouble about language,

technology and education. New York: Random House.

Propp, V. (1968). Morphology of the Folktale. (L. Scott, Trans.). Austin: University of

Texas. (Original work published in 1928).

Rhrich, L. (2008). "And They Are Still Living Happily Ever After": Anthropology,

Cultural History, and Interpretation of Fairy Tales. (P. Washbourne, Trans.).

Burlington: University of Vermont. (Original work published 2002).

Rosenthal, A. (1999). Why docudrama? Fact-fiction on film and TV. Southern Illinois,

IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Schopenhauer, A. (2008). The Art of literature and the art of controversy (T. B. Saunders

Trans.). Stilwell, KS: Digireads.com Publishing.

White, H. (1986). Damsels in distress: Dependency themes in fiction for children and

adolescents. Adolescence, 21 (82), 251-6.

Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news: a study in the construction of reality. New York: The

Free Press.

U.S. Office of Justice Programs. (2010). AMBER alert. Retrieved March 29, 2010, from

http://www.amberalert.gov/

28

Victimization & Drama in News

Table 1: Gender and Average Number of Narrative Elements

Narrative Elements

Male (n=45)

Female (n=91)

Conflict

1.7

1.6

.06

.95

Contrast

.80

.40

.80

.42

Dilemma

1.75

1.30

.52

.60

Empathy

1.34

1.19

.18

.86

Violence

1.57

1.59

-.021

.98

Sex

.80

1.13

-.43

.68

Innocence

1.57

1.63

-.07

.95

Vulnerable

1.77

1.71

.06

.95

Evil

.91

1.00

-.11

.91

Lurid Detail

.51

.81

.75

.52

Victimization & Drama in News

29

Table 2: Race and Average Number of Narrative Elements

Narrative Elements

White

Black

Hispanic

(n=69)

(n=28)

(n=37)

(2, 131)

Conflict

2.94 (6.92)a

.61 (1.37)

.08 (.36)b

4.67

.011**

Contrast

1.00 (3.67)

.07 (.262)

.00 (.00)

2.24

.111

Dilemma

2.49 (6.32) a

.57 (1.52)

.16 (.44) b

3.71

.028**

Empathy

2.23 (6.08) a

.32 (.86)

.08 (.27) b

3.64

.029**

Violence

2.81 (7.06) a

.64 (1.63)

.00 (.00) b

4.19

.017**

Sex

1.88 (5.74)

.25 (1.32)

.00 (.00)

3.05

.051

Innocence

2.86 (7.24) a

.46 (1.40)

.16 (.37) b

3.99

.021**

Vulnerable

3.06 (7.50) a

.54 (1.57)

.16 (.44) b

4.23

.017**

Evil

1.77 (5.95)

.29 (1.32)

.00 (.00)

2.44

.091

Lurid Detail

1.35 (4.73)

.11 (.56)

.03 (.16)

2.37

.097

Note. Means that do not share subscripts differ at p < .05 in the F test within the same

predictor. Values in parentheses are standard deviations.

Victimization & Drama in News

30

Table 3: Age and Average Number of Narrative Elements

Narrative

0-5

6-10

11-15

16-20

Elements

(n=65)

(n=27)

(n=26)

(n=16)

(3,130)

Conflict

1.00 (2.51) a

4.15 (9.96)b

1.62 (3.59)

.25 (1.00)

2.96

.035**

Contrast

.14 (.429) a

1.78 (5.60) b

.42 (1.57)

.19 (.750)

2.61

.054

Dilemma

1.03 (2.59)

3.15 (9.13)

1.38 (2.98)

.38 (1.08)

1.64

.182

Empathy

.62 (1.42) a

3.67 (9.32) b

.69 (1.71)

.56 (1.99)

3.48

.018**

Violence

.85 (2.74) a

4.15 (10.16) b

1.46 (3.14)

.44 (1.50)

2.94

.036**

Sex

.22 (.82) a

3.33 (8.67) b

1.15 (2.78)

.19 (.54)

3.90

.010**

Innocence

.89 (2.18) a

4.37 (10.74) b

1.12 (2.55)

.69 (2.75)

3.13

.028**

Vulnerable

.97 (2.22) a

4.52 (11.14) b

1.38 (3.06)

.69 (2.75)

2.98

.034**

Evil

.12 (.875) a

3.59 (9.00) b

.77 (2.28)

.31 (1.25)

4.50

.005**

Lurid Detail

.25 (1.03) a

2.41 (7.18) b

.54 (1.72)

.13 (.50)

2.85

.040**

Note. Means that do not share subscripts differ at p < .05 in the F test within the same

predictor. Values in parentheses are standard deviations.

31

Victimization & Drama in News

Table 4: Age, Race and Average Number of Narrative Elements

Narrative

Elements

Conflict

Contrast

Dilemma

Empathy

Violence

Sex

Innocence

Vulnerable

Evil

Lurid Detail

Age

Category

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

0-5

6-10

11-15

16+

White

Children (n) m

(31) 1.87

(15) 6.80

(13) 3.00

(10) .40

(31) .23

(15) 3.20

(13) .85

(10) .30

(31) 1.90

(15) 5.00

(13) 2.46

(10) .60

(31) 1.13

(15) 6.13

(13) 1.38

(10) .90

(31) 1.61

(15) 6.73

(13) 2.77

(10) .70

(31) .45

(15) 5.53

(13) 2.31

(10) .30

(31) 1.65

(15) 7.20

(13) 2.08

(10) 1.10

(31) 1.81

(15) 7.40

(13) 2.54

(10) 1.87

(31) .23

(15) 6.00

(13) 1.54

(10) .50

(31) .48

(15) 4.13

(13) 1.08

(10) .20

Black

Children (n) m

(15) .33

(9) 1.11

(4) .50

(0) .00

(15) .13

(9) .00

(4) .00

(0) .00

(15) .27

(9) 1.11

(4) .50

(0) .00

(15) .20

(9) .67

(4) .00

(0) .00

(15) .33

(9) 1.22

(4) .50

(0) .00

(15) .00

(9) .78

(4) .00

(0) .00

(15) .27

(9) 1.00

(4) .00

(0) .00

(15) .27

(9) 1.11

(4) .25

(0) .00

(15) .07

(9) .78

(4) .00

(0) .00

(15) .00

(9) .33

(4) .00

(0) .00

Hispanic

Children (n) m

(19) .11

(3) .00

(9) .11

(6) .00

(19) .00

(3) .00

(9) .00

(6) .19

(19) .21

(3) .00

(9) .22

(6) .00

(19) .11

(3) .33

(9) .00

(6) .00

(19) .00

(3) .00

(9) .00

(6) .00

(19) .00

(3) .00

(9) .00

(6) .00

(19) .16

(3) .33

(9) .22

(6) .00

(19) .16

(3) .33

(9) .22

(6) .00

(19) .00

(3) .00

(9) .00

(6) .00

(19) .05

(3) .00

(9) .00

(6) .00

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

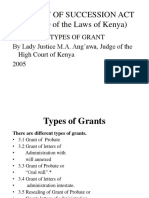

- Types of GrantsDocument44 pagesTypes of Grantseve tichaNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL LAW 1 MIDTERM EXAMDocument6 pagesCRIMINAL LAW 1 MIDTERM EXAMKD Frias100% (1)

- LETDocument14 pagesLETBai MonNo ratings yet

- Convergences and Divergences in The Pak US RelationsDocument3 pagesConvergences and Divergences in The Pak US RelationsZulfqar Ahmad100% (1)

- PSYCHOLOGY OF THE SELFDocument19 pagesPSYCHOLOGY OF THE SELFHanna Relator Dolor100% (1)

- PPL vs. RitterDocument7 pagesPPL vs. RitterCistron ExonNo ratings yet

- Sampling Methods in Research Methodology How To Choose A Sampling Technique For ResearchDocument11 pagesSampling Methods in Research Methodology How To Choose A Sampling Technique For ResearchRhem Rick CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Glancy Commission Submits ReportDocument2 pagesGlancy Commission Submits ReportZulfqar Ahmad100% (2)

- Surah Ya Seen Aks WWW - Alkalam.pkDocument8 pagesSurah Ya Seen Aks WWW - Alkalam.pklankyrck100% (3)

- Social FactsDocument5 pagesSocial FactsDivya Mathur50% (2)

- Roznama Dunya About Genral Assambly Resolution Regarding Kashmir PDFDocument3 pagesRoznama Dunya About Genral Assambly Resolution Regarding Kashmir PDFZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Kainat K Aajeeb Raaz PDFDocument166 pagesKainat K Aajeeb Raaz PDFZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Roznama Dunya Abot AkbarDocument3 pagesRoznama Dunya Abot AkbarZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Kainat K Aajeeb Raaz PDFDocument166 pagesKainat K Aajeeb Raaz PDFZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Mcqs by KashuDocument27 pagesChemistry Mcqs by KashuZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- 1211 1Document29 pages1211 1Zulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Roznama Dunya About HitlerDocument3 pagesRoznama Dunya About HitlerZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Single Paper DMC With Interview MarksDocument1 pageSingle Paper DMC With Interview MarksZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Roznama Dunya About Genral Assambly Resolution Regarding KashmirDocument3 pagesRoznama Dunya About Genral Assambly Resolution Regarding KashmirZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- ASP + AC + SO and Non - Tech - Syllabus - 2Document4 pagesASP + AC + SO and Non - Tech - Syllabus - 2Ali SikanderNo ratings yet

- GEPCO online bill detailsDocument2 pagesGEPCO online bill detailsZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Zulfqar Ahmad Sir Phool Nawaz: Editorial On School Dropout at Primary LevelDocument4 pagesZulfqar Ahmad Sir Phool Nawaz: Editorial On School Dropout at Primary LevelZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Pak-Afghan Relations, Hanif KhanDocument20 pagesPak-Afghan Relations, Hanif KhaninvntrsNo ratings yet

- Biology Intermediate McqsDocument140 pagesBiology Intermediate McqsSatram DasNo ratings yet

- 01 Pak-US Security RelationDocument24 pages01 Pak-US Security RelationZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Education in PakistanDocument5 pagesEducation in PakistanNauman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Parts of Sppech1 PDFDocument42 pagesParts of Sppech1 PDFmshakeel1994No ratings yet

- ChronologyDocument3 pagesChronologyZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- 02 AshrafDocument40 pages02 AshrafAbdullah AfzalNo ratings yet

- Devolution of PowerDocument6 pagesDevolution of PowerZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Enzyme Miracle in UrduDocument84 pagesEnzyme Miracle in UrduMuhammad Iqbal100% (2)

- Current Affairs MCQsDocument16 pagesCurrent Affairs MCQsZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Climate ChangeDocument8 pagesClimate ChangeZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Css Easy PaperDocument4 pagesCss Easy PaperZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- EnergyDocument5 pagesEnergyZulfqar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Expand Idea Proverbs 5 StepsDocument2 pagesExpand Idea Proverbs 5 StepsZaheer Ahmed TanoliNo ratings yet

- Sample MemorialDocument26 pagesSample MemorialShr33% (3)

- cll30 6Document12 pagescll30 6GlaholtLLPNo ratings yet

- Mgmt1135 2014 Sem-1 CrawleyDocument9 pagesMgmt1135 2014 Sem-1 CrawleyDoonkieNo ratings yet

- (Cô Vũ Mai Phương) Tài liệu LIVESTREAM - Tổng ôn 2 tuần cuối - Dự đoán câu hỏi Collocation trong đề thiDocument2 pages(Cô Vũ Mai Phương) Tài liệu LIVESTREAM - Tổng ôn 2 tuần cuối - Dự đoán câu hỏi Collocation trong đề thiMon MonNo ratings yet

- LAW6CON Dealing With Defective WorkDocument13 pagesLAW6CON Dealing With Defective WorkKelvin LunguNo ratings yet

- Cui V Cui 1957Document3 pagesCui V Cui 1957Angelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- Ashish CopyrightDocument22 pagesAshish CopyrightashwaniNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics and Corporate Governance 60 HoursDocument2 pagesBusiness Ethics and Corporate Governance 60 HoursTHOR -No ratings yet

- 61 Maquera V BorraDocument2 pages61 Maquera V BorraCarie LawyerrNo ratings yet

- Recovery of Possession of Immoveable PropertyDocument5 pagesRecovery of Possession of Immoveable PropertyEhsanNo ratings yet

- Alan Jenkins FinalDocument2 pagesAlan Jenkins FinallibreybreroNo ratings yet

- Name of Local Body Issuing CertificateDocument1 pageName of Local Body Issuing CertificateMuhammad RaadNo ratings yet

- LA3 Reflective Journal #2 - FinalDocument3 pagesLA3 Reflective Journal #2 - FinalRavish Kumar Verma100% (1)

- BPI V. DE COSTER: Agent Cannot Make Principal Liable for Third Party DebtsDocument2 pagesBPI V. DE COSTER: Agent Cannot Make Principal Liable for Third Party DebtsTonifranz Sareno100% (1)

- Ethics Lesson 1-3Document18 pagesEthics Lesson 1-3Bhabz KeeNo ratings yet

- 9 Moral Dilemmas That Will Break Your BrainDocument11 pages9 Moral Dilemmas That Will Break Your BrainMary Charlene ValmonteNo ratings yet

- Fields IndictmentDocument8 pagesFields IndictmentJenna Amatulli100% (1)

- Legal Case Report GuideDocument7 pagesLegal Case Report GuideCheong Hui SanNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Values: A Comparison Between Four Countries (United States, Brazil, United Kingdom and Canada)Document15 pagesEthics and Values: A Comparison Between Four Countries (United States, Brazil, United Kingdom and Canada)ahmedNo ratings yet

- Studi Tentang Dalalah Makna: Absolutisme Dan Relatifisme Ayat-Ayat Hukum Dalam Al-Qur'anDocument20 pagesStudi Tentang Dalalah Makna: Absolutisme Dan Relatifisme Ayat-Ayat Hukum Dalam Al-Qur'anSyarifah Zuhra Al-ba'budNo ratings yet

- Updated Group Assignment Questions Group A3Document5 pagesUpdated Group Assignment Questions Group A3Richy X RichyNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocument5 pagesRhetorical Analysisapi-317991229No ratings yet

- 8th Grade Sexual Harassment PresentationDocument19 pages8th Grade Sexual Harassment PresentationSoumen PaulNo ratings yet