Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Critique On The Methodology of Avi Hurvitz

Uploaded by

PPablo LimaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Critique On The Methodology of Avi Hurvitz

Uploaded by

PPablo LimaCopyright:

Available Formats

THE YOBEL SPRING

Festschrift to

REV. DR. CHILKURI VASANTHA RAO

on his 50th Birthday

Edited by

Praveen S. Perumalla,

Royce M. Victor

&

Naveen Rao

2013

554

The Yobel Spring

The Yobel Spring

555

of the Bible for Christian farmers in South India, we cannot but read the

Bible with new eyes, because of the listening and observing engagement

in the midst of the agricultural communities.

3.

Moving Beyond

Ecumenism and Inter-faith relations has come a long way and continues

to discover new and relevant paradigms for ministry and mission.

However, paradigms cannot emerge from centres of ecumenism, but needs

decentring. As we envision our world as God creation and the possibility

of inhabiting it, the possibility of human existence with each other and in

harmony with Gods creation is becoming increasingly violent and

disturbing. It is in this context that we need to revisit Ecumenism and

Inter-faith relations from the point of hermeneutics with the broad lens

of identity and difference. Human issues cannot be divorced from the

issues of ecology, because the role of human beings in sustaining creation

is directly related to the rights of human beings. We all have a shared

history and a shared future, and we need to move beyond harmony to

engage with the other, defined by each other.

Endnotes

1

Michael Kinnnamon and Brian E. Cope, The Ecumenical Movement: An

Anthology of Key Texts and Voices,(Geneva: WCC Publications, 1997), 1.

2

Kinnamon and Cope, The Ecumenical Movement, 3 -4

Kinnamon and Cope, The Ecumenical Movement, 4.

4 Michael Kinnamon, The Vision of the Ecumenical Movement and How It Has

Been Impoverished by Its Friends, (Missouri: Chalice Press, 2003), 106.

5 Anthony C. Thiselton, New Horizons in Hermeneutics, (Grand Rapids:

Zondervan Publishing House, 1992), 48.

6 Thiselton, New Horizons, 48.

7 Anthony C. Thiselton, The Two Horizons (Carlisle: The Paternoster Press, 1980),

xix.

3

8 Felix Wilfred, Asian Public Theology.Critical Concerns in Challenging Times

(Delhi: ISPCK, 2010), 213.

9 David Tracy, Plurality And Ambiguity. Hermeneutics, Religion, Hope (London:

SCM Press, 1987), 50.

10

Tracy, Plurality And Ambiguity, 72. See also p.79

www.hardnewsmedia.com/2010/02 (accessed on April 4, 2012; The big five

states where farmer suicides are taking place are Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh,

Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. On n average, a farmer dies

every 30 minutes.

11

GNANARAJ D.

A Critique on the Linguistic

Methodology of avi hurvitz and its

Application to the Dating of Qoheleth

Introduction

iblical linguists unanimously acknowledge that Avi Hurvitzs1

contribution to the diachronic linguistic studies has been

phenomenal and remain widely recognized in recent decades.2

According to Rooker, the individual, who has unquestionably contributed

the most to the diachronic study of Biblical Hebrew, certainly in the last

quarter of the twentieth century, is Avi Hurvitz 3 His diachronic

linguistic methodology has been extensively used by mainstream linguists

to analyze the chronological significance of multifarious linguistic features

found across the Biblical corpus and especially in the dating of texts often

considered problematic.4 Needless to say, his methodology has shaped

the landscape of Biblical linguistics and wielded an unrivaled influence

since 1970s until recent years.

When Hurvitz constructed his linguistic methodology, there was a

general consensus among the mainstream scholarship that Qoheleth is a

post-exilic composition, with considerable concentration of late linguistic

features. Though he did not systemically apply his methodology to

Qoheleth until 2007, he subscribed to the then general consensus that

Qoheleth belonged to the late date, along with certain post-exilic books.

He simply states, the only working hypothesis concerning chronology is

that such books as Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles, Esther, Ecclesiastes, etc

556

The Yobel Spring

were written during the Post-Exilic period. This, of course, is universally

accepted.5

As far the book of Qoheleth is concerned, its language has triggered

several controversies over the past decades.6 The linguistic heterogeneity

and complexity of Qoheleth has forced scholars to construe often novel

explanations: Burkitt, Zimmermann, Ginsberg and Torrey called it as a

translation from the Aramaic original,7 Dahood identified CananitePhoenician influence upon its language,8 Gordis claimed the influence of

Mishnaic Hebrew upon its language9 and Lohfink and Leo Perdue claimed

the influence of Greek over Qoheleth.10 There is lack of consensus among

these scholars concerning the date of Qoheleth.11 Mainstream scholarship

dates it well into the Hellenistic era, in line with the tradition that started

earlier with Delitzsch and Gordis, ably augmented by the recent studies

of Antoon Schoors. However, it is the underlying methodological

framework of Hurvitz that has given the mainstream position an aura of

invincibility within current scholarship. Recently, he applied his

methodology to Qoheleth and reiterated the majority position that it is a

post-exilic book.12

This paper outlines the four basic principles that are the foundational

pillars of Hurvitzs methodology, a review of the recent debate over

Hurvitzs methodology and the problems of applying this method to

Qoheleth with a concise evaluation at the end.

Methodological Rationale of Hurvitz

Hurvitzs methodology is, in general, appreciated for its emphasis on the

objective examination of the Biblical texts and its ability to assist in the

process of determining a date for difficult texts. He recognized the element

of subjectivity in prior methods used in dating problematic texts and the

pressing need for structuring rigorous criteria which promises impartial

results. He voiced his concern as follows:

Unfortunately, the theological, historical and literary criteria which have

been used for establishing the date of chronologically problematic texts

are very often subjective. Linguistic studies likewise did not produce

satisfactory results, since they were not usually based upon

methodologically reliable criteria.13

This identification of the above crisis as well as the need for a sound

methodology led him to develop his own methodology. His assumptions

and rationale show reservations in dating a problematic text hastily to a

particular period based on scantly attested linguistic features. However,

The Yobel Spring

557

the preliminary notion that the Hebrew of the pre-exilic period is noticeably

different from the Hebrew of the post-exilic period is axiomatic to Hurvitzs

methodology. It was during the Babylonian exile (586 BCE), that the

increasing interaction of Hebrew with Aramaic, the official language of

the Babylonian Empire, effected in language change resulting in the

transition from Standard Biblical Hebrew (or Classical Biblical Hebrew)

to Late Biblical Hebrew and finally to Mishnaic Hebrew (or, Rabbinic

Hebrew).14 Without such assumption at the core, Hurvitzs methodology

would not stand.

The four pillars of Hurvitzs paradigm, found in his 1973 article, are

briefly summarized as follows: 15

1.

The [linguistic] element should appear only, or mainly, in such

Biblical books as Daniel, Ezra or Esther; i.e., in books which all

scholars accept as late (Late Frequency).

2.

There should be alternative elements found in earlier books which

express the same meaning (Linguistic Opposition).

3.

The element in question should be vital (in regular use) in postexilic sources other than LBH (= Late BH) for instance, in BA (=

Biblical Aramaic) or MH (= Mishnaic Hebrew) (External sources).

4.

The text will not be considered late unless it manifests numerous

late elements one or two isolated examples can always be

interpreted as a coincidence (Linguistic Accumulation).

He also outlined a similar methodology for determining the chronological

significance of Aramaisms in BH.16 His methodology became the sole

underlying principle in all of his writings as well as of those scholars who

followed the diachronic dating of Biblical texts after his lead. These

premises of Hurvitzs methodology has remained constant and been

sustained with predominant mainstream support until Youngs criticism

in the recent years.

Major Conclusions of Hurvitz

Hurvitzs inherent premise is that the linguistic profiles of pre-exilic Biblical

books are different from that of the post-exilic books and that the earlier

vocabularies and constructions functioned with divergent semantics and

grammatical horizons. He perceives the Babylonian exile as a definite

influential factor in the chronological development of Hebrew language.17

He terms the language of Pre-exilic Hebrew as Standard Biblical Hebrew

558

The Yobel Spring

(SBH = Classical / Early Biblical Hebrew) and the language of Post-exilic

Hebrew as Late Biblical Hebrew (LBH). The end of SBH is pointed to be

around 6th century BCE.18 And the book of Ezekiel is identified with the

transitional kind of Hebrew that stands between SBH to LBH.19 Hence,

the Pentateuch and the former prophets (up to the Book of Kings) are said

to be written in SBH and belongs to the period before 500 BCE, and books

like Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah, Esther are said to contain typical LBH

forms and features that belong chronologically to a later period. His study

focuses mainly on the lexical features that appear in SBH books and

contrasts them with that in the LBH corpus and vice-versa in order to

determine their chronological placement. His main foundation was

lexicographical, rather than grammatical.20

Hurvitz had support from the major research of Robert Polzin who

undertook an ambitious21 study of mainly tracing 19 grammatical features

in Chronicles, and P sections from Pentateuch, former prophet, Esther

and Ezra-Nehemiah to determine their Chrono-linguistic placement within

the Biblical corpus.22 He proposed the order of Biblical books based on

their linguistic profiles, i.e., based on the frequency of such LBH features

in these books: the more the congruency, the book was identified with

LBH; lesser the congruency, it was attributed to Classical Hebrew (JE, Dtr,

and the Court History). He identified P with transitional Hebrew and

Chronicles as an example of LBH. Like Hurvitz, he also began his research

with the assumption that Babylonian exile had serious repercussions on

Hebrew language. In several points, he affirms the works of Hurvitz, with

regard to Aramaisms, the traceability of the linguistic development within

the Biblical corpus, among others.

However, the main focus of Polzins work remained on grammatical

foundations, which he rightfully rationalized as more objective than the

lexicographical features.23 While Hurvitz cites Ezekiel as an example for

transitional Hebrew, Polzin finds the transitional patterns in P. In view of

the language of the inscriptions such as Lachish and Arad Ostraca, Polzin

takes them to be closer to LBH (but Hurvitz places them in late monarchicera, at the end of First Temple Period). Polzin does not detect any

archaizing tendencies in Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah [2] 24 whereas

Hurvitz affirms various degrees of archaism in all LBH books. Regardless

of these differences, the working methodologies and the conclusions of

these two scholars have provided a solid foundation for the subsequent

studies which mainly emphasized the diachronic developments of the

The Yobel Spring

559

Hebrew language within Biblical books. Their methodologies combined

together came to be known as the Hurvitz-Polzin paradigm.25

Qoheleth and the Methodology Of Hurvitz

Qoheleth has often been identified as late work due to its linguistic

idiosyncrasy that is, according to the methodology of Hurvitz,

characteristic of the transitional Hebrew of LBH/MH. This section briefly

reviews the premise and the conclusions of Tylors study on the language

of Qoheleth which employed the methodology of Hurvitz and further

discusses few misleading cases from the recent studies on the language

of Qoheleth.

Tylors Application of Hurvitzs Methodology

When the consensus of dating Qoheleth to the Hellenistic era (around 250

BCE) was indisputably on the side of the mainstream scholarship, Louis

Ray Tylor undertook his doctoral dissertation in order to verify whether

such a persuasive conclusion could be arrived by the systematic application

of Hurvitzs methodology upon the language of Qoheleth.26 Here, it is

important to point that there were two other similar major studies being

conducted in different parts of the world almost at the same time, each

independent of the other, tackling similar question in their research.27

Taylor stated at the outset that he would follow the methodology of

Hurvitz to approach the language of Ecclesiastes. He states,

The methodology in dating Ecclesiastes will be that of Hurvitz. If a

considerable clustering of late features are found in Ecclesiastes, the book

will be proved late The alleged sign of lateness in question must not

only be widely current in post-586 Hebrew, but it must also be nonexistent or at least nearly so in texts which are indisputably early. 28

The above statement by Taylor is an obvious reference to the principle of

linguistic accumulation as advocated by Hurvitz. After a review of the

current state of the studies and survey of literature, Tylor, in his Chapter

III and IV, focuses on sixty six lexical items that were considered to be the

indications of lateness.29 He does a comprehensive survey of its usage in

Biblical as well as extra-Biblical literature to come to the objective

conclusion on each of its place in the history of the Hebrew language. He

concludes that only six items were found to be definite signs of late date

(k vr already, lat domineer, h min except, z mn time, hfe

delight, bal cease) nine found to be possible indications lateness (mae whatever, lmm long duration, knas gather, ytr superiority,

560

The Yobel Spring

sf end, ibbah praise, tqf overpower, malxt kingdom, and ill

if/though); one word appears only in Proverbs, Song of Songs and in

Ecclesiastes (Solomonic Corpus) q street; and two words might

indicate northern influence (z and rct).30

In Chapter V, he engages the grammar of Ecclesiastes as a criterion

for dating. Two features, he studies here are orthography and verbs. He

analyzes the orthography of hy, h briefly and spends considerable

amount of discussion on the verbs of Qoheleth: the perfective aspect,

imperfective aspect, the infinitive, the participle, waw consecutive, finalh and final l f verbs. He makes important observations concerning the

absence of vowel letters which he supposes as the indication of early date

or Phoenician influence. As far orthography, he says, the orthography of

Ecclesiastes certainly does not accord with the spelling of MH, whose

orthography was much more plain than that of BH.31 His conclusion on

the morpho-syntactic study of the verb categorizes Ecclesiastes firmly

within SBH. He also observes the lack of clear grammatical direction in

Qoheleth.32

He concedes that the tabulation of grammatical forms is ambiguous

and does not attest to any particular direction. However, he goes on to

argue that this indecisiveness is, in fact, the answer. He states,

Yet this inconclusiveness of the findings is an answer to scholars who

have assumed that the language of Ecclesiastes proves the book late.

Examination of the vocabulary of Ecclesiastes yielded only six truly late

items. This small number, a in a book of twelve chapters, does not

constitute a histabbrt nikkeret considerable clustering of late elements

(Hurvitz, 1966:28f).33

Taylor also interpreted the two Persian words in Qoheleth in a different

light and did not categorize them as chronologically significant: nor would

Aramaic and Persian words in themselves prove a Post-Solomonic date,

for Solomon was a cosmopolitan king, who conducted trade and

intercourse with Phoenicia and other countries (1 Kings 4:21/5:1; 4:24/

5:4; 4:34/5:14; 5:1/15; 7:13; 9:11ff; 10:1-11, 15, 22). 34

In his summary, Taylor evidently states that there is no considerable

clustering of clearly late items in Ecclesiastes, the book is not proved late.

Yet insufficient evidence was found to prove early authorship either.35

So, here we see the case that the application of the methodology of Hurvitz

on Qoheleth has led to the conclusion that it cannot be dated late based

on its language. The question resoundingly emerges here, What could be

the reason behind such indecisiveness in the application of a methodology

The Yobel Spring

561

that is widely practiced and appreciated by the majority scholarship? a question deservingly in need of further elucidation.

Methodologically Misleading Cases

A few lexicographical and grammatical features, such as the use of 1cs,

relative pronoun that are often treated as late are briefly discussed below.

Here is an exemplary case of the linguistic frequency. Qoheleths

exclusive use of n (28 times) and his total avoidance of nok (0 times)

caused much speculation. Generally, as Schoors observes, nok is more

frequent than n in the older literature, whereas in the LBH, the frequency

of the latter increases.36 Schoors moves on to conclude that all the

evidence seems to point to a late phase of BH, close to MH, as far as

Qoheleths use of the 1cs personal pronoun is concerned.37 However,

this confident conclusion of Schoors was recently disputed by Holmstedt.38

He argues that the above deduction was invalid and over-simplistic in its

treatment of n:

Does Qoheleth really exhibit a peculiar use of the pronouns, as

Schoors asserts? Not at all. Qoheleths use of pronouns reflects syntactic

options that are well represented throughout the Biblical corpus of

ancient Hebrew the post-verbal pronoun strategy reflects the authors

rhetorical skill and linguistic ingenuity, it is masterful use of language,

neither odd nor ungrammatical.39

Here, let us discuss an example of linguistic accumulation. In Qoheleth,

the relative pronoun e occurs 68 times along with er (89 times).40 For

Schoors, the increasing usage of e was diachronically important that he

concluded with respect to the relative pronoun, that Qoh belongs to a

later phase of the language, standing midway between BH and MH.41

He reasoned that being shorter in form e must have replaced er in the

LBH. There are few things to observe here: overall, there are 139

occurrences of e in the Hebrew Bible of which 68 are in Qoheleth and 32

are in Song of Songs, both belonging to Solomonic corpus. The remaining

39 occurrences are scattered across the Hebrew Bible (Genesis 6:3, Jud 5:7

[twice], 6:17, 7:12, 8:26, 2 Kings 2:11) and do not provide the needed ground

to conclude that it is a traceable late feature. It has probably been attributed

to the poetic choice of the writer than of diachrony. The appearance of e

in earlier passages is suggestive that it is not a distinctively late element.42

The increasing use of e in Qoheleth and in Song of Song (30 times) might

be due to its poetical, conversational-type, swift presentation model. Hence,

it has limited significance in Qoheleth as a chronological marker. Recently,

562

The Yobel Spring

Hurvitz conceded that the occurrences of the relative pronoun in Qoheleth

are not strictly of diachronic consequence.43

Here is an example of attestation by external sources. The phrase kl

ser hps sh (he does whatever he pleases) in Qoh 8:3 is used by

Hurvitz as a pointer of Qoheleths later date of composition. Hurvitz cites

five references (Ps 115:3, 135:6, Jonah 1:14, Isa 46:10 and Eccl 8:3) and

observes that it was used only in conjunction with God or an earthly king

and argues that it belongs to the domain of jurisprudence.44 According

to him, the expression he does whatever is good in his sight is the

standard idiom before 500 BCE, whereas he does everything he desires

is the expression of choice after 500 BCE.45 He contrasts Qoh 8:3 with an

Aramaic inscription, Sefire Steles from the 8th Century BCE, to arrive at

this conclusion. Here, Youngs word of caution on the epigraphic materials

has much wisdom, however, one should hesitate to draw far reaching

conclusions on the basis of such meager evidence. 46 The problem of

relating epigraphic materials within the various phases of BH has its own

limitations, as skillfully pointed by Young.

We see an inconclusiveness and uncertainty caused by the

methodology of Hurvitz on several levels. The above brief study has

pointed how the application of the principles of Hurvitzs methodology,

such as linguistic frequency, linguistic accumulation and external sources

can be misleading. Along with these features, a host of other linguistic

features are attributed to the LBH/MH influence in the language of

Qoheleth: predominant use of participles, the presence of the two Persian

words, Aramaic influence, infrequent use of consecutive imperfects, the

wide use of direct object marker, the feminine demonstrative zh, the third

masculine plural pronominal suffix for feminine plural antecedents, and

the negation of infinitive with n (there is no).

A Critique on Hurvitzs Methodology on Qoheleth

At the outset, one need to be reminded of the fact that though the

methodology of Hurvitz was meticulously composed, its central emphasis

was upon the lexical elements and while applied on books such as Haggai

and Zachariah an apparent post-exilic works, it was found inadequate

to demonstrate their lateness; rather these books, according to the result

of Hurvitzs methodology showed greater resemblance to the language of

pre-exilic era.47 Polzins approach based on the levels of congruenceincongruence, also dated Zachariah to the date of Pg corpus, not alongside

Chronicles or Ezra or N [2].48 Such methodologically inconsistent results

The Yobel Spring

563

evoke the need for sharpening these methodologies or structuring newer

paradigms. I will proceed to briefly list six criticisms on the methodology

of Hurvitz and its application to the language of Qoheleth.

Firstly, the central assumption of Hurvitz that the pre-exilic Hebrew

(SBH) did not exist beyond exile and was replaced by LBH in the postexilic era has come under serious scrutiny in the recent scholarship. Dong

Hyuk Kim, in a recent dissertation from Yale, points out that it is no longer

possible to hold such an uncanny view and further states that, Hurvitz

has consistently argued that it is the exilic period that decisively separates

LBH from EBH in form and in chronology... However, our empirical

analysis suggests that we can no longer hold on to such an understanding

of the exilic period.49 There is much more continuity in the language in

general than often thought or portrayed by the proponents of diachronic

method. Kim categorizes Qoheleth along with books with disputed or

undecided dates, and concurs with Young that it is difficult to date it in

late post-exilic date only based on linguistic evidence.50

Second, Hurvitz-Polzins studies were all conducted in the narrative

prose of Chronicles, Former prophets, Esther, Ezra-Nehemiah, Ezekiel,

among others. There was no complete treatment of the language of

Qoheleth, nor did any other poetical books receive comprehensive

treatment based on Hurvitz-Polzin paradigm.51 Ironically, as Qoheleth

reflects some of the supposed late features both on grammatical as well

as lexicographical levels, it has been taken for granted that Qoheleth should

be counted along with LBH books. In fact, it is worth noting that Qoheleth

is the only book which has a semi prosaic-poetical language in comparison

to the other books that are currently marked as LBH corpus. It seems like

such distinctions have not received due attention.

Third, another important factor to consider is the nature of the book

of Qoheleth. It is the only philosophical work of this kind in the Hebrew

Bible. While Chronicles had a definite referral point in the books of SamuelKings, Qoheleth has been repeatedly referred to the post-Biblical book

like Ben Sira.52 Qoheleth is a unique philosophical-wisdom composition

within the Biblical corpus. The Hurvitz-Polzin paradigm that works based

on the earlier-later comparison of linguistic features did not satisfactorily

explain the peculiarities of the language of Qoheleth, as it has no early

point of reference to contrast with.

Fourth, a serious criticism of the methodology of Hurvitz has to do

with its somewhat fixated emphasis upon the chronological conclusion

564

The Yobel Spring

for linguistic variations in the text. This approach, ipso facto, denies the

plausibility that a Biblical author could have employed a peculiar style of

language for a specific reason. It tends to confine the text strictly within

the world of a chronological stratum. This issue has been ably raised by

Young and Rezetko, Is chronology the only or best explanation for

linguistic variety in Biblical texts? To what degree do other (strictly

speaking) non-chronological factors, such as dialect and diglossia, account

for the different linguistic profiles of Biblical texts?53 There should be

space for allowing such flexibility, which is not plausible within the current

paradigm of Hurvitz. Ironically, the assumed objectivity of this

methodology turns out to be its inevitable Achilles heel as well. 54

Fifth, from the perspective of the diachronic Hebrew model, it is being

widely believed that the extra-Biblical inscriptions and epigraphical

materials from various periods from the history of Hebrew languages serve

as external controls to date the Biblical books into various periods. 55 Such

delineations not only underlie the earlier works but are also found as part

of Hurvitzs methodology itself.56 The assumption that epigraphic Hebrew

corresponds to the Biblical Hebrew of various periods was challenged

recently.57 Young holds that the inscriptions show a more diverse linguistic

stratum than BH in general. More important is his observation on the

scarcity of inscriptions, Inscriptional Hebrew is best seen as an

independent corpus within ancient Hebrew There is a large gap in our

external sources for Hebrew between the last inscriptions dated to the

early sixth century BCE, and the first Dead Sea Scrolls in the third century

BCE.58 If such a view is accepted, then utilizing the external epigraphic

materials as controls become a daunting premise to affirm the dates of the

Biblical texts as early or late. It directly deprives the Hurvitzs methodology

of its significant pillar, something on which Hurvitz repeatedly relied upon.

Finally, an often insufficiently treated element in the diachronic study

of language of Qoheleth is the influence of northern dialects.59 Such

presence of dialects within pre-monarchial Palestine is found in Judges

12 (Shibboleth story).60 How does the methodology of Hurvitz tackle

the issue of dialectical influence? The comparison of pre-exilic and postexilic books is often helpful in tracing the linguistic changes in lexical levels,

yet it does not make concessions to consider the influences that cause such

changes in its methodology. In fact, the structure of written language, in

general, is more polished compared to conversational language. In a

philosophical work like Qoheleth where he conversantly discusses the

issues on the intricacies of life, laborious quest for its elusive meaning

The Yobel Spring

565

amidst perturbing tensions in a tongue of the general populace (12:9),61

the presence of dialects, and more specifically, how the dialectal presence

shaped the language of the entire discourse is yet to be explored at length.

And such legitimate questions fall beyond the methodological delineations

of Hurvitz, an intrinsic weakness of his methodology requiring serious

reworking.

These criticisms recognize the important methodological flaws within

the diachronic model of linguistic dating and account for the indecisive

results it produced when applied to Qoheleth. Employing this model to

evaluate the language of Qoheleth in itself should be deemed, at best,

insufficient, and should call for the serious revision of the existing model

or the formation of alternative linguistic methodologies in the near future.

Conclusion

It has to be pointed out that Avi Hurvitz constructed his diachronic

methodology to date Biblical texts mainly through the study of prosenarrative works. And his research was conducted using the techniques of

linguistic contrast between the early-late literatures of pre-exilic

(Deuteronomic History) and post-exilic works (Chroniclers History),

primarily on the lexical level. Systematic application of Hurvitz

methodology on the study of Qoheleth by Taylor was unable to

convincingly establish the late date for Qoheleth. The reason that emerged

from the current study is that Qoheleths language, being distinctive from

a prose narrative work and without any early point of reference to its

genre, presents challenges to the Hurvitzs diachronic model and reveals

its inadequacy to date Qoheleth with certainty.

On the other hand, the non-chronological model proposed by Young

and others, reading Qoheleth with its inherent monarchic background,

recognizes the presence of colloquialism, influence of genre, and assigns

a date in the late monarchy. The approach of Youngs synchronic

methodology was extremely critical of the prevalent method to the point,

casting a whiff of doubt upon the entire enterprise of diachronic linguistic

dating. It has to be deemed that such is the overstatement of the scenario.

I would like to concur with John Cook that tracing the diachronic linguistic

change is an objective phenomenon and linguistics offers usable models

and methods for discerning diachronic differences in the language of the

Biblical text.62 Yet, my contention is that applying the diachronic model

of Hurvitz without adjusting its parameters towards unique works like

Qoheleth tends to produce indecisive results, as it does not take into

566

The Yobel Spring

consideration the influence of dialectal presence, for instance, in its

restrictive equation. Synchronic explanations of Young and others, though

promising, would need time to evolve into a full-fledged field of study,

if they are successful in incorporating and working out their arguments

into a systematic methodology.

One of the major challenges for future language studies on Qoheleth

is how to move forward beyond this methodological impasse and labor

towards synthesizing the methodological parameters of the diachronic

model (Hurvitz) with the synchronic model (Young). Both have to be

interwoven into forming a more complete methodology to analyze a Book

like Qoheleth. Nevertheless, the challenge here is how one defines the

features belonging to genre influence, dialectal influence, scribal additions,

etc. That being said, its time for Biblical linguists to admit the limitations

of the application of Hurvitzs methodology to non-prosaic works in

general and Qoheleth in particular.

Bibliography

Books and Commentaries

D, Gnanaraj. The Language of Qoheleth: An Evaluation of the Recent Scholarly

Studies. New Delhi: ISPCK, 2012.

Fredericks, Daniel C. Qoheleths Language: Re-evaluating Its Nature and Date.

Ancient Near Eastern Texts and Studies 3. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin

Mellen, 1988.

The Yobel Spring

Seow, C. L. Ecclesiastes. Anchor Bible Commentary. New York: Double Day,

1997.

Tylor, Louis Ray. The Language of Ecclesiastes as a Criterion for Dating. Ann

Arbor, MI: UMI, 1988.

Young, Ian. Diversity in Pre-exilic Hebrew. Tbingen: JCB Mohr, 1993.

Young, Ian (ed.). Biblical Hebrew: Studies in Chronology and Typology. New York:

T&T Clark International, 2003.

Young, Ian, Robert Rezetko, and Martin Ehrensvrd. Linguistic Dating of Biblical

Texts. 2 Vols. London: Equinox, 2009.

Articles

Adams, William James Jr. and L. La Mar Adams, Language Drift and The

Dating of Biblical Passages. Hebrew Studies 18 (1977): 160-164.

Burkitt, F.C. Is Ecclesiastes a Translation? JHS 22 (1921): 22-23.

Cook, John. Detecting Development in Biblical Hebrew using Diachronic

Typology, In Dictionary in Biblical Hebrew. eds. Cynthia Miller-Naude

and Zinoy Zevit (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns): 1-51. Forthcoming.

Dahood, Mitchell. Canaanite Words in Qoheleth 10.20. Biblia 46 (1965): 210212.

. Canaanite-Phoenician Influence in Qoheleth. Biblia 33 (1952):

30-52.

. Qoheleth and North West Semitic Philology, Biblia 46 (1962):

349-365.

. Qoheleth and Recent Discoveries. Biblia 39 (1958): 302-318.

Fredericks, Daniel C and Daniel J. Estes. Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs. Apollos

OT Commentary 16. Nottingham, England: Apollos, 2010.

Ginsburg, H.L. Koheleth. Tel Aviv: M. Newman, 1961.

567

. The Language of Qoheleth CBQ 14 (1952): 227-232.

. The Phoenician Background of Qoheleth. Biblia 47 (1966):

264-282.

Hurvitz, Avi. A Linguistic Study of the Relationship of the Priestly source and the

Book of Ezekiel. Cahiers de la Revue Biblique. Paris: Gabalda, 1982.

Davila, James R. Qoheleth and Northern Hebrew. MAARAV 5-6 (Spring

1990): 69-87.

Isaksson, Bo. Studies in the Language of Qoheleth: With Special Emphasis on the

Verbal System. Th.D diss., Uppsala University, 1987.

Gordis, Robert. The Original Language of Qoheleth. JQR 38 (1946-47): 83;

Perdue, Leo G. The Sword and The Stylus: An Introduction to Wisdom in the Age

of Empires. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008.

. Wisdom Literature: A Theological History. Louisville:

Westminster John Knox Press, 2007.

. Was Qoheleth a Phoenician? Some Observations on the

Methods of Research JBL 74 (1955): 103-114.

Hill, A.E. Dating Second Zachariah: A Linguistic Reexamination, HAR 6

(1982): 105-134.

Polzin, Robert. Late Biblical Hebrew: Toward an Historical Typology of Biblical

Hebrew Prose. Missoula: Scholars, 1976.

Holmstedt, Robert D. n belibb: The Syntactic Encoding of the Collaborative

Nature of Qoheleths Experiment. Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9:19

(2009): 2-27.

Schoors, Antoon. The Preacher Sought to Find Pleasing Words: A Study of the

Language of Qoheleth Part I and II. Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 1992 and

2004.

. The distribution of er and eC in Qoheleth. SBL

Washington D.C (2006): 1-15.

568

The Yobel Spring

The Yobel Spring

569

Hurvitz, Avi. Linguistic Criteria for Dating Problematic Biblical Texts,

Hebrew Abstracts 14 (1973): 74-79.

Zimmermann, F. The Aramaic Provenance of Qohelet, JQR 36 (1945-46):

17-45.

. The Chronological Significance of Aramaisms in Biblical

Hebrew, Israel Exploration Journal 18:4 (1968): 234-240.

. The Inner World of Qoheleth. New York: Ktav Publishers, 1973.

. The Historical Quest for Ancient Israel and the Linguistic

Evidence of the Hebrew Bible: Some Methodological Observations.

VT 47/3 (1997): 301-315.

. The History of a Legal Formula: kl ser hps sh VT 32

(1982): 257-267.

. The Recent Debate on Late Biblical Hebrew: Solid Data,

Experts Opinions and Inconclusive Arguments. Hebrew Studies 47

(2006): 191-210.

Hurvitz, Avi. The Language of Qoheleth and Its Historical Setting within

Biblical Hebrew. in Berlejung A. and P. van Hecke (eds.,). The Language

of Qohelet in Its Context: Essays in Honour of Prof. A. Schoors on the Occasion

of His Seventieth Birthday (Leuven: Peeters, 2007): 23-34.

Joosten, Jan. The Syntax of Volitive Verbal Forms in Qoheleth in Historical

Perspective, in The Language of Qoheleth in context (Leuven: Peeters,

2007): 47 - 61.

Kim, Dong Hyuk. Early Biblical Hebrew, Late Biblical Hebrew and Linguistic

Variability: A Sociolinguistic Evaluation of the Linguistic Dating of Biblical

Texts. Yale University Dissertation, 2011. To be published by Brill in

Nov 2012.

Rooker, Mark F. Diachronic Analysis and the Features of Late Biblical

Hebrew, Bulletin for Biblical Research 4 (1994): 135-144.

Schoors, Antoon. The Pronouns in Qoheleth. Hebrew Studies 30 (1989):

Seow, C.L. Linguistic Evidence and the Dating of Qoheleth, JBL 115/4

(Winter, 1996): 643-666.

Torrey, C.C. The Question of Original Language of Qoheleth. JQR 39 (194849): 151-160.

Young, Ian. Evidence of Diversity in Pre-exilic Judahite Hebrew. HS 38

(1997): 7-20.

. Late Biblical Hebrew and Hebrew Inscriptions in Biblical

Hebrew, 276-311.

. The Style of the Gazer Calendar and Some Archaic Biblical

Hebrew Passages. VT XLII, 3 (1992): 362-375.

. Diversity in Pre-Exilic Hebrew. Tubingen: Coronet Books Inc,

1993.

Zevit, Ziony. What a Difference a Year Makes: can biblical texts be dated

linguistically? Hebrew Studies 47 (2006): 83-91.

Endnotes

1

Avi Hurvitz is a Casper Levias Professor Emeritus of Ancient Semitic

Languages at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJ) where he was a

professor since 1967. He widely contributed on the historical development of

the Hebrew Language and its relationship with other Semitic languages during

the biblical and post-biblical periods. Further information on Hurvitz can be

found in the HUJ website: http://www.huji.ac.il/dataj/controller/ihoker/MOPSTAFF_LINK?sno=299674&Save_t (Accessed on Oct 7, 2012).

2 Young respectfully acknowledges, In recent decades, the contribution of

Avi Hurvitz to this field has outweighed all his contemporaries. In numerous

books and articles, he has advanced and, indeed, shaped the current discourse

on the topic of diachronic variation in BH. Ian Young (ed.), Biblical Hebrew:

Studies in Chronology and Typology (New York: T&T Clark International, 2003),

1.

3 Mark F. Rooker, Diachronic Analysis and the Features of Late Biblical

Hebrew, Bulletin for Biblical Research 4 (1994), 136.

4 Hurvitz methodology appeared in two important articles in 1968 and 1973

in English. See, Avi Hurvitz, The Chronological Significance of Aramaisms in

Biblical Hebrew, Israel Exploration Journal 18:4 (1968): 234-240; Linguistic

Criteria for Dating Problematic Biblical Texts, Hebrew Abstracts 14 (1973): 7479.

5 Hurvitz: Linguistic Criteria, 75.

6

For a summary of the recent debates on the language of Qoheleth, see:

Gnanaraj D, The Language of Qoheleth: An Evaluation of the Recent Scholarly Studies

(New Delhi: ISPCK, 2012). Forthcoming. Mark Boda, Tremper Longman III and

Cristian Rata, Fresh Perspectives on Qohelet (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns).

7 F. C. Burkitt, Is Ecclesiastes a Translation? JHS 22 (1921), 22-23. F.

Zimmermann, The Aramaic Provenance of Qohelet, JQR 36 (1945-46): 17-45.

F. Zimmermann, The Inner World of Qoheleth (New York: Ktav Publishers, 1973),

128-131. C.C. Torrey, The Question of Original Language of Qoheleth, JQR 39

(1948-49), 152. H.L. Ginsburg, Koheleth (Tel Aviv: M. Newman, 1961).

8 Mitchell Dahood, Canaanite-Phoenician Influence in Qoheleth, Biblia 33

(1952), 30-52; The Language of Qoheleth CBQ 14 (1952), 227-232; Qoheleth

and Recent Discoveries, Biblia 39 (1958), 302-318; Qoheleth and North West

Semitic Philology, Biblia 46 (1962), 349-365; Canaanite Words in Qoheleth

10.20, Biblia 46 (1965), 210-212; The Phoenician Background of Qoheleth,

Biblia 47 (1966), 264-282

9 Robert Gordis, The Original Language of Qoheleth, JQR 38 (1946-47), 83;

Robert Gordis, Was Qoheleth a Phoenician? Some Observations on the Methods

of Research JBL 74 (1955): 103-114.

570

The Yobel Spring

10

Leo G. Perdue, Wisdom Literature: A Theological History (Louisville:

Westminster John Knox Press, 2007), 177-179. Norbert Lohfink, Qoheleth, A

Continental Commentary (trans. Sean McEvenue; Minnepolis: Fortress Press,

2003). Its a translation of a German original published in 1980. Though

Qoheleths dating is still a contentious issue, mainstream scholars assume

Hellenistic philosophical traces in Qoheleth. Fredericks observes this trend and

states it is primarily a presupposition of a Greek philosophical influence on

Ecclesiastes that has caused some to identify native Hebrew words and phrases

to Graecisms. Daniel C. Fredericks and Daniel J. Estes, Ecclesiastes and Song of

Songs, Appollos OT Commentary 16 (Nottingham, England: Apollos, 2010), 61.

Norbert Lohfink, Qoheleth, A Continental Commentary (trans. Sean McEvenue;

Minnepolis: Fortress Press, 2003). Its a translation of a German original

published in 1980. Concerning Graecisms in Qoheleth, Schoors is rather

ambiguous. He says, I am less sure about lexical Graecisms. There are no

compelling arguments to accept an important Greek influence on Qohs

vocabulary. However, the few acceptable parallels may strengthen the force of

Greek parallels in the domain of contents and thus be favourable to a date in

the Hellenistic period. Antoon Schoors, The Preacher Sought to Find Pleasing

Words, Part II: Vocabulary (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 2004), 501.

11 Bo Isaksson, Studies in the Language of Qoheleth: With Special Emphasis on the

Verbal System. Th.D diss., at Uppsala University, 1987; Daniel C. Fredericks,

Qoheleths Language: Re-evaluating Its Nature and Date. Ancient Near Eastern

Texts and Studies 3. (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 1988); Antoon Schoors, The

Preacher Sought to Find Pleasing Words: A Study of the Language of Qoheleth Part

I and II (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters, 1992 and 2004); C. L. Seow, Ecclesiastes.

Anchor Bible (New York: Double Day, 1997); Linguistic Evidence and the

Dating of Qoheleth, JBL 115/4 (Winter, 1996): 643-666. Ian Young, Diversity in

Pre-Exilic Hebrew (Tubingen: Coronet Books Inc, 1993); Ian Young, Robert

Rezetko, and Martin Ehrensvrd, Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts. 2 Vols.

(London: Equinox, 2009).

12 In his recent article in the Festschrift of Schoors, he affirms the fingerprints of LBH in Qoheleth. See, Avi Hurvitz, The Language of Qoheleth and

Its Historical Setting within Biblical Hebrew, in Berlejung A. and P. van Hecke

(eds.,), The Language of Qohelet in Its Context: Essays in Honour of Prof. A. Schoors

on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday (Leuven: Peeters, 2007): 23-34.

13

Hurvitz: Linguistic Criteria, 74.

Rooker quotes from Blount and Sanches who argue that external factors

such as invasions, conquests, contact, migrations, institutional changes,

restructuring and social movements produce language change. Rooker:

Diachronic Analysis, 143. See also, Ben G. Blount and Mary Sanches, Sociocultrual Dimensions of Language Change (New York: Academic Press, 1977), 4.

15Hurvitz: Linguistic Criteria, 76-77.

14

16

Hurvitz is against the simplistic conclusion that the very presence of

Aramaisms point to the later date for any Biblical literature. Hurvitz, The

Chronological Significance of Aramaisms in Biblical Hebrew, 234 240;

The Yobel Spring

571

Hebrew and Aramaic in the Biblical Period: The Problem of Aramaisms in

Linguistic Research of the Hebrew Bible, in Young, Biblical Hebrew, 34-37.

17 Avi Hurvitz, The Recent Debate on Late Biblical Hebrew: Solid Data,

Experts Opinions and Inconclusive Arguments, Hebrew Studies 47 (2006), 191.

18 Avi Hurvitz, Evidence of Language in Dating the Priestly Code: A

Linguistic Study in Technical Idioms and Terminology. Revue Biblique 81 /1

(1974), 26.

19 Avi Hurvitz, A Linguistic Study of the Relationship of the Priestly source and

the Book of Ezekiel, Cahiers de la Revue Biblique (Paris: Gabalda, 1982), 113.

20 Zevit observes about the emphasis of Hurvitz, he settled primarily on a

contrastive analysis of lexical items and some syntax Zevit: What a difference,

85.

21 Quoting the words of Zevit here: complementing Hurvitzs early

lexicographical work, was a single, ambitious study by Robert Polzin. He

gives the example for a situation where the combination of Hurvitz-Polzin

paradigm was applied and tested. Zevit: What a Difference, 86-87. R. Polzin,

Late Biblical Hebrew: Toward an Historical Typology of Biblical Hebrew Prose

(Missoula: Scholars, 1976).

22

It is said that Polzins monograph went on to become the most widely

cited publication on Late Biblical Hebrew in general. Young and Rezetko,

Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts, 25.

23

Polzin remarked, it appears to me that grammatical/syntactical features

are more efficient chronological indicators than are lexical features.. Polzin,

Late Biblical Hebrew, 15f, 123f.

24 Generally, N 2 identified with Nehemiah 7.6 12.26. N1 is identified with

Nehemiah 1.1-7.5; 12.27-13:31.

25

Zevit uses this phrase in his presentation at NAPH session (National

Association of Professors of Hebrew) that met during 2005 SBL meeting and a

year later the same was published in Hebrew Studies. This describes the current

trend in biblical studies well. See, Ziony Zevit, What a Difference a Year

Makes: can biblical texts be dated linguistically? HS 47 (2006), 89.

26 Tylors doctoral dissertation, supervised by Prof. Aaron Bar-Adon, was

submitted to the University of Texas in 1988. Unpublished dissertation: Louis Ray

Tylor, The Language of Ecclesiastes as a Criterion for Dating (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI,

1988).

27 Isakksons dissertation, submitted at the University of Uppsala and

published in 1987, focused on the Verbal system of Qoheleth and concluded

that the verbal system of Qoheleth remains within Biblical Hebrew than closer

to Mishnaic Hebrew. Daniel C. Fredericks, in an independent monograph

published in 1988, vigorously criticized the consensus of majority to the language

of Qoheleth and decisively dated it in Pre-exilic period. Bo Isaksson, Studies in

the Language of Qoheleth: With Special Emphasis on the Verbal System. Th.D diss.,

at Uppsala University, 1987; Daniel C. Fredericks, Qoheleths Language: Reevaluating Its Nature and Date. Ancient Near Eastern Texts and Studies 3.

572

The Yobel Spring

(Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 1988). It is particularly of interest due to the

independent nature of their research and relatively similar conclusions.

28 Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 14-15.

29 Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 39-275.

30

Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 299.

Taylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 280.

32 His views are sympathetic to that of Dahood and Archer in this regard

allowing the possibility of a Phoenicianizing tendency in the morpho-syntactical

features of Ecclesiastes. Taylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 294-295.

33 Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 300.

34 Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 300.

31

35

Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, vii.

Antoon Schoors, The Pronouns in Qoheleth, Hebrew Studies 30 (1989), 71.

Rooker also lists the use of n and nok as one of the commonly proposed

LBH features. Rooker: Diachronic Analysis, 144.

37 Schoors: The Pronouns in Qoheleth, 72.

38 See, Robert D. Holmstedt, n b elibb: The Syntactic Encoding of the

Collaborative Nature of Qoheleths Experiment, Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 9/

19 (2009): 2-27; the distribution of er and eC in Qoheleth, SBL Washington

D.C, (2006): 1-15.

39 Holmstedt: Syntactic Encoding, 20.

40 Isaksson observes that in Qoheleth a kind of equilibrium is at hand: er

57%, e against 43%... e is used more often in chapters 1 and 2. From ch.3 on

it is used more sparingly. er shows the highest frequency in ch. 7-9. Its

frequency is relatively high also 1 Ch. 3-5. Isaksson, Studies, 149.

41 Schoors, Pleasing Words, Vol 1, 56.

42 There are suggestions that e belong to either northern origin or a vernacular

element. However it also appeared in non-Northern texts as Gen 6:3.

43 Hurvits: The Language of Qoheleth: 31-32

44 Avi Hurvitz, The History of a Legal Formula: kl ser hps sh VT 32

(1982): 257-67.

45 Hurvitz: History of Legal Formula, 267. Hurvitz believes that the

comparative study of this Hebrew phrase with Aramaic helped him to pinpoint

its lateness to Persian period. However, its predominant appearance with God

might imply a religious language borrowed into court procedures later.

46 Young: Late biblical Hebrew and Hebrew Inscriptions, 310-311.

47 Zevit: What a Difference, 86.

36

48 See, A.E. Hill, Dating Second Zachariah: A Linguistic Reexamination,

HAR 6 (1982): 105 -134.

49 Kim sees the necessity to revise the traditional understanding of the

divide of BH, or the watershed moment in the history of BH. Dong Hyuk Kim,

Early Biblical Hebrew, Late Biblical Hebrew and Linguistic Variability: A Sociolinguistic

The Yobel Spring

573

Evaluation of the Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts, (Yale, 2011), 270-271. This

dissertation is slated for publication by Brill in November 2012.

50 Kim, Dating of Biblical Texts, 139.

51 Hurvitz had responded to Youngs non-chronological proposal in his recent

article on Qoheleths language. Its a limited lexical study, not a comprehensive

study on Qoheleths language. See, Avi Hurvitz, The Language of Qoheleth

and Its Historical Setting within Biblical Hebrew, in The Language of Qoheleth

in context (Leuven: Peeters, 2007): 23-34. Also see, J. Joosten, The Syntax of

Volitive Verbal Forms in Qoheleth in Historical Perspective, in The Language

of Qoheleth in context (Leuven: Peeters, 2007): 47-61.

52

See, Fredericks, Qoheleths Language, 111-117.

Young and Rezetko, Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts, 3.

54 Philip R. Davies argues that Hurvitzs methodology provides a nave

explanation of a complicated problem. He is radical in his criticism of Hurvitzs

methodology, because in its pseudo-scientific arrogance, it attempts to dismiss

other views as inadmissible. Philip R. Davies, Biblical Hebrew and the History

of Ancient Judah: Typology, Chronology and Common Sense, in Young, Biblical

Hebrew, 163.

53

55

William James Adams, Jr., L. La Mar Adams state that since the dating

of the parts of the Old Testament is much debated, it was decided to analyze all

available Hebrew inscriptions which date to Old Testament times as control text.

[Emphasis added]. Their idea that Hebrew was replaced by Aramaic as a

vernacular during the post-exilic period is now abandoned. Currently, Hebrew

was believed to have been spoken well into the first C.E. They were so confident

that the inscriptions point to the certain chronological periods in the history

Hebrew language: a) Early date level (900-700 BC) Mesha Stone, Siloam

Inscription, Samaritan Calendar; b) Middle date level (700-586 BC) Lachish

Letters, Arad Ostraca, etc; c) Late date level (586-458 BC) no inscriptions; d)very

late level (458-100 BC) Manual of Discipline and DSS. William James Adams, Jr.,

L. La Mar Adams, Language Drift and The Dating of Biblical Passages, HS 18

(1977), 160-164. Such optimism is no more plausible in current scholarship, especially

with regards to the epigraphic materials.

56

Hurvitz argued, [Non-biblical] sources provide us with the external

control required in any attempt to detect and identify diachronic developments

within BH.... by and large, there is a far-reaching linguistic uniformity underlying

both the pre-exilic inscriptions and the literary biblical texts written in Classical

BH. Avi Hurvitz, The Historical Quest for Ancient Israel and the Linguistic

Evidence of the Hebrew Bible: Some Methodological Observations, VT 47/3

(1997), 307-308. This similar idea is also found in his methodology, point 3.

Rooker, following Hurvitz asserted that the observations from linguistic contrast

and linguistic distribution] may be reinforced when extra-biblical parallels from

the Dead Sea Scrolls or rabbinic materials are considered. Rooker: Diachronic

Analysis, 137.

57 For the comprehensive treatment of extra-biblical inscriptions, see Young,

Diversity, 97-121. I. Young, The Style of the Gazer Calendar and Some Archaic

Biblical Hebrew Passages, VT XLII, 3 (1992): 362 375. I. Young, Late Biblical

574

The Yobel Spring

The Yobel Spring

Hebrew and Hebrew Inscriptions in Biblical Hebrew, 276-311. I. Young,

Evidence of Diversity in Pre-exilic Judahite Hebrew, HS 38 (1997), 8. Young

makes this perceptive observation, we should not, of course, dogmatically

assert that the inscriptions give us the full range of possible early Hebrews.

Nevertheless, the best reading of the evidence at hand would place the Bible in

its current form no earlier than the Persian period However, one should

hesitate to draw far reaching conclusions on the basis of such meager evidence.

Young: Late biblical Hebrew and Hebrew Inscriptions, 310-311.

58 Young: Biblical Texts, 344.

59 See, James R. Davila, Qoheleth and Northern Hebrew, MAARAV 5-6

(Spring 1990):69-87. Davila is positive that the dialect of Qoheleth was

influenced by northern Hebrew; however, he hopes that further discoveries

will give us more information in this regard. Davila: Qoheleth and Hebrew,

87.

60 Tylor cautions to treat the subject of dialectal influence and the presence

of northern Aramaisms carefully since the identified northern forms are few.

Tylor, Language of Ecclesiastes, 4

61 Seow: Linguistic Evidence, 666.

62 Forthcoming. John Cook, Detecting Development in Biblical Hebrew using

Diachronic Typology, In Dictionary in Biblical Hebrew, ed., Cynthia Miller-Naude

and Zinoy Zevit (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns), 2.

http://

ancienthebrewgrammar.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/cook-diachtypo-finaldraft.pdf

(Accessed on Oct 10, 2012).

575

BETHEL KRUPA VICTOR

Witnessing Christ Today in

Local Congregation:

Feminist Perspective

Introduction

n simple terms local congregation is a body of Christian believers,

consisting of members of all categories and age groups. The local

congregation plays a prominent role in promoting kingdom values

towards the transformation of the society. It is a widely accepted fact that

the local congregation is sustained by women and womens work is the

backbone to this body of Christ. Women take active part in all the activities

of the church. However, their work and efforts, and talents are not

recognized or utilized fully. In general, womens services to the church

are considered as an extension of the housewifes role of women, and

thus these tasks are taken for granted and unrecognized. In history, we

read of women who were engaged in a wide spectrum of ministries and

much of the ministry of the women was in mission a gift of love, given

in a voluntary capacity. However, the Bible shows clearly that witnessing

to Christ is a spiritual responsibility of women in the local congregation.

The Christian gospel would not have been proclaimed if the women

disciples kept silent. It has reached the ends of the earth because they

took up the responsibility of sharing the love of God through Jesus Christ

and witnessed it. At the local congregational levels, culture, tradition,

language, customs, practices and beliefs are the basic elements through

which they can actively participate in Gods Mission. Witnessing to Christ

You might also like

- Joosten (2005) The Distinction Between Classical and Late Biblical Hebrew As Reflected in Syntax PDFDocument13 pagesJoosten (2005) The Distinction Between Classical and Late Biblical Hebrew As Reflected in Syntax PDFrmspamaccNo ratings yet

- The Aramaic Maranatha in 1 Cor 16 22. TRDocument12 pagesThe Aramaic Maranatha in 1 Cor 16 22. TRartaxerxulNo ratings yet

- Fisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptDocument13 pagesFisseha Jewish Temple in EgyptGeez Bemesmer-LayNo ratings yet

- Kartveit, Theories of Origin of Samaritans (2019)Document14 pagesKartveit, Theories of Origin of Samaritans (2019)Keith Hurt100% (1)

- Nicolls-A Grammar of The Samaritan Language-1838 PDFDocument152 pagesNicolls-A Grammar of The Samaritan Language-1838 PDFphilologusNo ratings yet

- Cuneiform Signs Flashcards 9-14 of Huehnergard's Akkadian GrammarDocument2 pagesCuneiform Signs Flashcards 9-14 of Huehnergard's Akkadian Grammarspikeefix100% (1)

- A Story of Educational Philosophy in AntiquityDocument21 pagesA Story of Educational Philosophy in AntiquityAngela Marcela López RendónNo ratings yet

- Cuneiform Signs Flashcards For Huehnergard Akkadian Introduction Chapters 9-14 FRONTDocument2 pagesCuneiform Signs Flashcards For Huehnergard Akkadian Introduction Chapters 9-14 FRONTspikeefixNo ratings yet

- What Is Aramaic - John HuehnergardDocument12 pagesWhat Is Aramaic - John HuehnergardideboerNo ratings yet

- The Old Aramaic Inscriptions From Sefire: (KAI 222-224) and Their Relevance For Biblical StudiesDocument12 pagesThe Old Aramaic Inscriptions From Sefire: (KAI 222-224) and Their Relevance For Biblical StudiesJaroslav MudronNo ratings yet

- The Semantics of A Political ConceptDocument29 pagesThe Semantics of A Political Conceptgarabato777No ratings yet

- Hittite King PrayerDocument44 pagesHittite King PrayerAmadi Pierre100% (1)

- The Heritage of Imperial Aramaic in Eastern AramaicDocument27 pagesThe Heritage of Imperial Aramaic in Eastern Aramaictargumin0% (1)

- Kaufman Akkadian Influences On Aramaic PDFDocument214 pagesKaufman Akkadian Influences On Aramaic PDFoloma_jundaNo ratings yet

- Language and Linguist Compass - 2016 - Horesh - Current Research On Linguistic Variation in The Arabic Speaking WorldDocument12 pagesLanguage and Linguist Compass - 2016 - Horesh - Current Research On Linguistic Variation in The Arabic Speaking Worldrowan AttaNo ratings yet

- A Cultural History of Aramaic From The BDocument20 pagesA Cultural History of Aramaic From The BMatthew DavisNo ratings yet

- Aram Soba 5758Document346 pagesAram Soba 5758diederikouwehandNo ratings yet

- Theodore's Liturgical Mysticism of Fear and AweDocument9 pagesTheodore's Liturgical Mysticism of Fear and AweLeonardo CottoNo ratings yet

- Spirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdDocument330 pagesSpirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdfcocajaNo ratings yet

- Ylvwryb Tyrb (H Hjysrbynwah: (Z" (VT) Hdwhy RBDM Twlygmbv TymrahDocument10 pagesYlvwryb Tyrb (H Hjysrbynwah: (Z" (VT) Hdwhy RBDM Twlygmbv TymrahGian Nicola PaladinoNo ratings yet

- Gene Green, Lexical Pragmatics and The LexiconDocument20 pagesGene Green, Lexical Pragmatics and The Lexiconrobert guimaraesNo ratings yet

- Ehll Phoenician Punic PDFDocument9 pagesEhll Phoenician Punic PDFRodrigo MendesNo ratings yet

- 2018 Subrouping of The Semitic LanguagesDocument2 pages2018 Subrouping of The Semitic LanguagesStefan Mihajlovic100% (1)

- EtymDictVol3 PDFDocument1,045 pagesEtymDictVol3 PDFJason SilvestriNo ratings yet

- Brock - Introduction To Syriac StudiesDocument31 pagesBrock - Introduction To Syriac StudiesArthur Logan Decker III100% (1)

- Gelb, Amorite AS21, 1980Document673 pagesGelb, Amorite AS21, 1980Herbert Adam StorckNo ratings yet

- Tyro's Greek and English LexiconDocument792 pagesTyro's Greek and English Lexiconthersitesslaughter-1100% (2)

- (Surath Kthob) Mark Robert Meyer - Joseph Bali - George Anton Kiraz - The Syriac Peshi Ta Bible With English Translation. Exodus.-Gorgias Press (2017)Document289 pages(Surath Kthob) Mark Robert Meyer - Joseph Bali - George Anton Kiraz - The Syriac Peshi Ta Bible With English Translation. Exodus.-Gorgias Press (2017)B a Z LNo ratings yet

- Tatian's Diatessaron: The Arabic Version, The Dura Europos Fragment, and The Women WitnessesDocument43 pagesTatian's Diatessaron: The Arabic Version, The Dura Europos Fragment, and The Women Witnessesmehmet nuriNo ratings yet

- Nathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureDocument272 pagesNathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureBibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNo ratings yet

- ABRAMOWSKI-GOODMAN, A Nestorian Collection of Christological Texts 1Document120 pagesABRAMOWSKI-GOODMAN, A Nestorian Collection of Christological Texts 1kiriloskonstantinovNo ratings yet

- PAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical HebrewDocument25 pagesPAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical Hebrewivory2011No ratings yet

- Syriac Phillips1866 oDocument223 pagesSyriac Phillips1866 oCristianeDaisyWeberNo ratings yet

- 2015 Foreign Kings in The Middle Assyria PDFDocument34 pages2015 Foreign Kings in The Middle Assyria PDFVDVFVRNo ratings yet

- BINS 146 Peters - Hebrew Lexical Semantics and Daily Life in Ancient Israel 2016 PDFDocument246 pagesBINS 146 Peters - Hebrew Lexical Semantics and Daily Life in Ancient Israel 2016 PDFNovi Testamenti Lector100% (1)

- A Quack, How Unapproachable Is A PharaohDocument24 pagesA Quack, How Unapproachable Is A PharaohPedro Hernández PostelNo ratings yet

- Muraoka A GREEK-HEBREW TWO-WAY INDEX TO THE LXX (2010) - Parole Ebraico-GrecoDocument395 pagesMuraoka A GREEK-HEBREW TWO-WAY INDEX TO THE LXX (2010) - Parole Ebraico-GrecoDepacom SeminarioNo ratings yet

- Examining the Trinity in the Writings of Justin MartyrDocument5 pagesExamining the Trinity in the Writings of Justin MartyrVlachorum SapiensNo ratings yet

- Uwe Vagelpohl - The Prior Analytics in The Syriac and Arabic TraditionDocument25 pagesUwe Vagelpohl - The Prior Analytics in The Syriac and Arabic TraditionVetusta MaiestasNo ratings yet

- Studies in Semitic and Afroasiatic Linguistics - ChicagoDocument0 pagesStudies in Semitic and Afroasiatic Linguistics - ChicagoСергей БизюковNo ratings yet

- Compendious Syriac Dictionary 1903Document652 pagesCompendious Syriac Dictionary 1903blue&pink100% (2)

- Imperial Aramaic Lingua FrancaDocument20 pagesImperial Aramaic Lingua FrancaTataritos100% (1)

- The Dead Sea Scrolls. Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts With English TranslationsDocument2 pagesThe Dead Sea Scrolls. Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts With English TranslationsLeandro VelardoNo ratings yet

- Do Jews Have Dealings With Samaritans SV 76 2011Document31 pagesDo Jews Have Dealings With Samaritans SV 76 2011Anonymous Ipt7DRCRDNo ratings yet

- Blum, Solomon & United Monarchy Some Textual EvidDocument20 pagesBlum, Solomon & United Monarchy Some Textual EvidKeith HurtNo ratings yet

- 30 Sirach Nets PDFDocument49 pages30 Sirach Nets PDFJohnBusigo MendeNo ratings yet

- Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and HistoricityDocument323 pagesBiblical Narratives, Archaeology and HistoricityMarcelo Martin MOSCANo ratings yet

- Do Sages Increase Peace in The World?Document19 pagesDo Sages Increase Peace in The World?Dennis Beck-Berman0% (1)

- Ancient Hebrew MorphologyDocument22 pagesAncient Hebrew Morphologykamaur82100% (1)

- Archaeology and Philology On Mons Claudianus 1987Document12 pagesArchaeology and Philology On Mons Claudianus 1987Łukasz IlińskiNo ratings yet

- Micro-Corpus Codification in The Hebrew Revival: Moshe NahirDocument11 pagesMicro-Corpus Codification in The Hebrew Revival: Moshe NahirSailesh NimmagaddaNo ratings yet

- Zamazalová - 2010 - Before The Assyrian Conquest in 671 BCE PDFDocument32 pagesZamazalová - 2010 - Before The Assyrian Conquest in 671 BCE PDFjaap.titulaer5944No ratings yet

- (VTS 170) Eidsvag - The Old Greek Translation of Zechariah PDFDocument282 pages(VTS 170) Eidsvag - The Old Greek Translation of Zechariah PDFCvrator MaiorNo ratings yet

- Scribal Repertoires in EgyptDocument437 pagesScribal Repertoires in EgyptAdam T. AshcroftNo ratings yet

- Scribes, Scribal Hands and Palaeography," in Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies, Eds., A Companion To Linear B. Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World. Volume 2, 2011, Pp. 33-136.Document106 pagesScribes, Scribal Hands and Palaeography," in Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies, Eds., A Companion To Linear B. Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World. Volume 2, 2011, Pp. 33-136.Olia Ioannidou100% (2)

- Jews and Godfearers at Aphrodisias: Greek Inscriptions with CommentaryFrom EverandJews and Godfearers at Aphrodisias: Greek Inscriptions with CommentaryNo ratings yet

- Avicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyFrom EverandAvicenna's Theory of Science: Logic, Metaphysics, EpistemologyNo ratings yet

- Israel's Scriptures in Early Christian Writings: The Use of the Old Testament in the NewFrom EverandIsrael's Scriptures in Early Christian Writings: The Use of the Old Testament in the NewNo ratings yet

- Conversations at the Well: Emerging Religious Life in the 21st-Century Global World: Collaboration, Networking, and Intercultural LivingFrom EverandConversations at the Well: Emerging Religious Life in the 21st-Century Global World: Collaboration, Networking, and Intercultural LivingNo ratings yet

- Understanding Relations Between Scripts II: Early AlphabetsFrom EverandUnderstanding Relations Between Scripts II: Early AlphabetsNo ratings yet

- The Dead Sea Scrolls in Recent Scholarship: A Virtual Public ConferenceDocument12 pagesThe Dead Sea Scrolls in Recent Scholarship: A Virtual Public ConferencePPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Timiadis EDocument2 pagesTimiadis EPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Ceiso2015 Rus WebDocument2 pagesCeiso2015 Rus WebPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Abstracts Fall of Jerusalem 27-28 March 2015Document6 pagesAbstracts Fall of Jerusalem 27-28 March 2015PPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- SONNET J.-P. The Fifth Book of The Pentateuch. DT in Its Narrative Dynamic JAJ 3.2Document38 pagesSONNET J.-P. The Fifth Book of The Pentateuch. DT in Its Narrative Dynamic JAJ 3.2PPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Ceiso2015 Rus WebDocument2 pagesCeiso2015 Rus WebPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Deuteronomio Sforno REDUCEDDocument7 pagesDeuteronomio Sforno REDUCEDPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Deuteronomio Ibn Ezra REDUCED PDFDocument12 pagesDeuteronomio Ibn Ezra REDUCED PDFPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Deuteronomio Rashbam REDUCEDDocument17 pagesDeuteronomio Rashbam REDUCEDPPablo Lima100% (1)

- Deuteronomio Ramban REDUCEDDocument9 pagesDeuteronomio Ramban REDUCEDPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- MCKENZIE S.L. AYBD. Deuteromistic Source and SchoolDocument16 pagesMCKENZIE S.L. AYBD. Deuteromistic Source and SchoolPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- MILLER P. D. The Many Faces of Moses in Dt. BR 04 - 05Document7 pagesMILLER P. D. The Many Faces of Moses in Dt. BR 04 - 05PPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- YOUNGBLOOD R.F. Qoheleth's Dark House Eccl 12.5Document14 pagesYOUNGBLOOD R.F. Qoheleth's Dark House Eccl 12.5PPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- BRETÓN S. Qohelet StudiesDocument29 pagesBRETÓN S. Qohelet StudiesPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- ALMENDRA L.M. The Central Enigma of God's Justice, According To Job 32-37Document9 pagesALMENDRA L.M. The Central Enigma of God's Justice, According To Job 32-37PPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Some SongsDocument1 pageSome SongsPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Elenchus of Biblica. Don MeredithDocument2 pagesElenchus of Biblica. Don MeredithPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- The Psalms of SolomonDocument255 pagesThe Psalms of SolomonOto-obong Umoren100% (1)

- Labuschagne. The Compositional Structure of The Psalter PDFDocument29 pagesLabuschagne. The Compositional Structure of The Psalter PDFPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- SONNET J.P. Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh Gods Narrative IdentityDocument21 pagesSONNET J.P. Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh Gods Narrative IdentityPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- BARBOUR J. The Story of Israel in The Book of QoheletDocument2 pagesBARBOUR J. The Story of Israel in The Book of QoheletPPablo Lima100% (1)

- CLEMENS D.M. The Law of Sin and Death. Ecclesiastes and Genesis 1-3Document4 pagesCLEMENS D.M. The Law of Sin and Death. Ecclesiastes and Genesis 1-3PPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Ecclesiastes Bibliography 4 03 PDFDocument39 pagesEcclesiastes Bibliography 4 03 PDFPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Boyarin D. A Radical JewDocument253 pagesBoyarin D. A Radical JewPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Ecclesiastes Bibliography PDFDocument90 pagesEcclesiastes Bibliography PDFPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Statement Catholic JewishDocument3 pagesStatement Catholic JewishPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Catholics TattoosDocument1 pageCatholics TattoosPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- Evangelicals and MaryDocument21 pagesEvangelicals and MaryPPablo LimaNo ratings yet

- MANTHRASDocument62 pagesMANTHRASVaithy Nathan100% (1)

- FSI - Swedish Basic Course - Student TextDocument702 pagesFSI - Swedish Basic Course - Student TextAnonymous flYRSXDRRe100% (6)

- 188048-Inglés B2 Comprensión Escrita SolucionesDocument2 pages188048-Inglés B2 Comprensión Escrita SolucionesTemayNo ratings yet

- Guide To Contemporary Music in Belgium 2012Document43 pagesGuide To Contemporary Music in Belgium 2012loi100% (1)

- Revised 2012 Greek Placement Exam Study GuideDocument6 pagesRevised 2012 Greek Placement Exam Study GuideÁriton SimisNo ratings yet

- Criticism To Speech Act TheoryDocument2 pagesCriticism To Speech Act TheoryMalena BerardiNo ratings yet

- Sahlins - Goodbye To Triste TropesDocument25 pagesSahlins - Goodbye To Triste TropeskerimNo ratings yet

- 40 Rohani Ilaj PDFDocument12 pages40 Rohani Ilaj PDFMuhammad TalhaNo ratings yet

- Tenses In English: A Comprehensive GuideDocument76 pagesTenses In English: A Comprehensive Guidemusa_ks100% (1)

- ArabicDocument113 pagesArabicLenniMariana100% (12)

- Time Table for Spring 2022 Semester 2Document15 pagesTime Table for Spring 2022 Semester 2fati sultanNo ratings yet

- Chou Literature Circles For Graded ReadersDocument21 pagesChou Literature Circles For Graded Readersradina anggunNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of 'Two WordsDocument3 pagesCritical Analysis of 'Two Wordskay kayNo ratings yet

- INTERROGATIVE WORDS QUIZDocument12 pagesINTERROGATIVE WORDS QUIZcarmenbergsancNo ratings yet

- English Grammar CohesionDocument1 pageEnglish Grammar Cohesionbutterball100% (1)

- Derrida's Deconstruction of Saussure's Structuralist LinguisticsDocument15 pagesDerrida's Deconstruction of Saussure's Structuralist LinguisticsJaya govinda raoNo ratings yet

- Alroya Newspaper 12-05-2013Document24 pagesAlroya Newspaper 12-05-2013Alroya NewspaperNo ratings yet

- First Grade Wow WordsDocument22 pagesFirst Grade Wow WordsAnonymous BhGelpV100% (5)

- WritingDocument20 pagesWritingNga NguyenNo ratings yet

- Feelings PDFDocument10 pagesFeelings PDFLorena VaraNo ratings yet

- Anita Desai - in Custody PDFDocument68 pagesAnita Desai - in Custody PDFArturoBelano958% (12)

- VenkateshwarluDocument2 pagesVenkateshwarluNaveenNo ratings yet

- Arabic Origins of Perceptual and Sensual Terms in EnglishDocument13 pagesArabic Origins of Perceptual and Sensual Terms in EnglishHüseyinBaşarıcıNo ratings yet

- Varro Marcus Terentius 116 To 27 B.C. by D J TaylorDocument1 pageVarro Marcus Terentius 116 To 27 B.C. by D J TaylorNandini1008No ratings yet

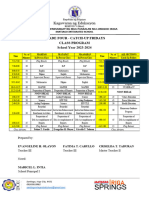

- Class Program G4 Catch UpDocument1 pageClass Program G4 Catch UpEvangeline D. HertezNo ratings yet

- EC - A2 - Tests - Unit 3 Answer Key and ScriptDocument3 pagesEC - A2 - Tests - Unit 3 Answer Key and ScriptEdawrd Smith50% (2)

- Comparative and SuperlativeDocument2 pagesComparative and SuperlativeRebecca Ramanathan100% (1)

- Arabic Alphabet Made Easy #1 Alef and Nun: Lesson NotesDocument3 pagesArabic Alphabet Made Easy #1 Alef and Nun: Lesson NotesminoasNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Instructional Planning (Iplan)Document15 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Instructional Planning (Iplan)Faith Castillo-EchavezNo ratings yet

- АТк 03 22Document9 pagesАТк 03 22Айкөкүл СопукуловаNo ratings yet