Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Herder's Heritage and The Boundary-Making Approach: Studying Ethnicity in Immigrant Societies

Uploaded by

petry51209Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Herder's Heritage and The Boundary-Making Approach: Studying Ethnicity in Immigrant Societies

Uploaded by

petry51209Copyright:

Available Formats

Herder's Heritage and the Boundary-Making Approach: Studying Ethnicity in Immigrant

Societies

Author(s): Andreas Wimmer

Source: Sociological Theory, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Sep., 2009), pp. 244-270

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40376136

Accessed: 07-05-2015 05:47 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Sociological Theory.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Herder'sHeritageand the Boundary-Making

Approach:

in Immigrant

Societies*

StudyingEthnicity

Andreas Wimmer

Departmentof Sociologyat UCLA

research,includingassimilationtheory,multiMajor paradigms in immigration

and ethnicstudies,take itfor grantedthatdividingsocietyintoethnic

culturalism,

because each of thesegroupsis

groupsis analyticallyand empirically

meaningful

characterized

and sharedidentity.

by a specificculture,densenetworks

of solidarity,

Threemajor revisionsof thisperspectivehave been proposedin the comparative

ethnicityliteratureover thepast decades, leading to a renewedconcernwiththe

research,"asemergenceand transformation

of ethnicboundaries.In immigration

similation"and ''integration'

as potentiallyreversible,

have been reconceived

powerdrivenprocesses of boundaryshifting.Aftera syntheticsummaryof the major

theoretical

propositionsof thisemerging

paradigm,I offersuggestionson how to

it

andfactors

to

in

research.

First,majormechanisms

bring

fruition futureempirical

thedynamicsof ethnicboundary-making

are specified,emphasizingthe

influencing

I thendiscuss

need to disentanglethemfromotherdynamicsunrelatedto ethnicity.

a seriesofpromisingresearchdesigns,mostbased on nonethnic

unitsof observation

andfactors.

and analysis,thatallowfor a betterunderstanding

of thesemechanisms

This articleaims to advance the conversationbetweenstudentsof comparativeethThis conversationhas given rise to a new

nicityand scholars of immigration.1

concernwithethnicboundary-making

in immigrant

societies.Insteadof treatingeth- providingself-evident

units of analysisand

nicityas an unproblematicexplanans

variables

the

as an extakes

self-explanatory

ethnicity

boundary-making

paradigm

planandum,as a variableoutcomeof specificprocessesto be analyticallyuncovered

and empirically

has particularadspecified.The ethnicboundary-making

perspective

societies,as a numberof authorshave suggested

vantagesforthe studyof immigrant

recently.

*Address

correspondenceto: Andreas Wimmer,264 Haines Hall, Los Angeles,CA 90095. E-mail:

awimmer@soc.ucla.edu.Earlierversionsof thisarticlewerepresentedat the conference"Grenzen,Differenzen,Ubergange"organizedby the VolkswagenFoundationin Dresden 2006, at anotherVolkswagen

sponsoredworkshopon "Concepts and Methods in MigrationResearch" in Berlinin Novemberof that

year,at the Center on Migration,Policy,and Society of OxfordUniversityin February2007, at the

Ecole des hautes etudesen travailsocial of Geneva in March 2007, and at the workshopon "Changing

Boundaries and EmergingIdentities"at the Universityof Gottingenin June2008. Special thanksgo

to Richard Alba, Rainer Baubock, Homi Bhaba, Sin Yi Cheung,Han Entzinger,HartmutEsser,David

Gellner,Ralph Grillo, Raphaela Hettlage,Frank Kalter, Matthias Konig, Frank-OlafRadtke, Karin

DimitrinaSpencer,StevenVertovec,Susanne Wessendorf,and Sarah Zingg Wimmerfor

Schittenhelm,

comments.I thank Claudio Bolzmann, WilhelmKrull, Karin Schittenhelm,

Steve Vertovec,Matthias

Konig, and Claudia Diehl for invitingme to the above venues. My departmentalcolleagues Rogers

Brubaker,Adrian Favell, and Roger Waldingerofferedgenerousadvice and criticismthat I wish I had

been able to take more fullyinto account. Wes Hiers was kind enough to carefullyedit the finalversion

(and to teach me that"that" and "which"are not the same).

!The argumentofferedhere draws on Wimmer(1996, fromwhichthe titleis adapted) and Wimmer

and Glick Schiller(2002). For othercritiquesregardingthe (ab)use of the conceptof ethnicity,

see Bowen

(1996) and Brubaker(2004:Ch. 1) forconflictresearch,Brubaker(2004:Ch. 2) for studieson collective

and Steinberg(1981) forimmigration

studies.

identity,

SociologicalTheory27:3 September2009

AmericanSociologicalAssociation.1430 K StreetNW, Washington,

DC 20005

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

245

This articlebringstogetherthesevarious worksand offersan integratedaccount

is

of themain theoreticalpropositionsthatunderliethem.First,immigrant

ethnicity

thatspans theboundarybetweenmajority

conceivedas theoutcomeof an interaction

thus involvingactors fromboth sides and creatingboth immigrant

and minority,

and nationalmajoritiesin theprocess.Second, immigrant

minorities

incorporationis

of the boundariesof belonging,whichhas to overcomeexisting

definedas a shifting

formsof social closure along ethniclines. In this process,immigrantsstrategically

tryto adopt culturalmarkersthat signifyfullmembershipand distancethemselves

fromstigmatizedothersthroughboundarywork.

After elaborating these basic theoretical propositions associated with the

I offerconcreteresearchavenues

ethnicity,

approachto immigrant

boundary-making

and

boththecausal mechanismsof ethnicboundary-making

thatwillhelp to identify

the main factorsthat affectits varyingoutcomes.Taking labor marketintegration

and segregationas an example,I arguethatto understandthemakingand unmaking

of ethnicboundarieson labor markets,researchersshould focus theirattentionon

the interplayof institutionalrules (e.g., welfarestate regulations,diploma recognition,etc.), resourcedistribution

(of educationaland economiccapital),and networks

of hiringand credit,whichmay or may not formalong ethniclines. In order to

avoid an ethnicreadingof immigrant

incorporationprocesseswhereit is empirically

inadequate,special attentionis paid to the problemof how to disentangleethnic

fromother,nonethnicprocessessuch as the generalworkingsof

boundary-making

class reproduction.

The concludingsectionfocuseson theresearchdesignsmostappropriateforuncov- a kind of menu fromwhichI hope

eringthesevarious mechanismsand processes

scholars will choose in conductingfutureresearch.I recommendnonethnicunits

of observation,which make it possible to see whetherethnicgroups and boundor dissolved- ratherthan

aries emerge,and how theyare subsequentlytransformed

assumingtheirrelevanceand continuityby takingethnicgroups as units of observation and analysis.Reviewinga series of recentand ongoing researchprojects,I

discuss the potentialof analyzingspatial entities(such as urban neighborhoods),

domains (such as schools or workplaces).

social classes,individuals,or institutional

Researcherswho findit meaningfulto studythe fateof membersof a specificimmigrantbackgroundare offeredsuggestionson how to avoid some of the pitfallsthat

have characterizedstudiesof immigrant

ethnicityin the past.

These pitfallsand theoreticaldeficienciesare subjectedto a systematic

critiquein

the nextsection.I show thatsome of the major paradigmsof immigration

research,

and ethnicstudies,

includingvariousstrandsof assimilationtheory,multiculturalism,

unitsof observationand analysis,

all concur in takingethnicgroupsas self-evident

assumingthat this is the most meaningfulway of dividingsocietyinto groups of

individuals.To varyingdegrees,theyalso take it forgrantedthateach ethnicgroupis

This

and sharedidentity.

endowedwitha specificculture,communitarian

solidarity,

variables

and

of

observation

units

self-evident

as

of

self-explanatory

ethnicity

concept

Stormand

derives,as will be shown,fromthe writingsof the anti-enlightenment,

StressphilosopherJohannGottfriedHerder.

Three decades of comparativeresearchhave shownthattheseHerderianassumptionsare problematicbecause theyhold onlyfora subsetof ethnicgroupsand thus

cannot be seen as generalfeaturesof ethnicityper se. In manyinstances,members

of ethniccategoriesmightnot share the same culture,mightnot forma "community"held togetherby denselywovensocial networks,and mightdisagreeabout the

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

246

Examrelevanceof different

ethniccategoriesand thusnot hold a commonidentity.

iningthedynamicsof ethnicboundary-making

helpsto avoid theHerderianontology

of the social world and to arriveat a more adequate understandingof ethnicity's

role in processesof immigrant

adaptation.

HOW NOT TO THINK ABOUT ETHNICITY

In the eyes of 18th-century

philosopherJohannGottfriedHerder,the social world

was populated by distinctpeoples, analogous to the species of the naturalworld.

Ratherthan dividinghumanityinto "races" dependingon physicalappearance and

innatecharacter(Herder 1968:179) or rankingpeoples on the basis of theircivilizational achievements(Herder 1968:207,227), as was common in Frenchand British

writingsof the time,Herder insistedthat each people representedone distinctive

manifestation

of a sharedhumancapacityforcultivation(or Bildung)(e.g. 1968:226;

but see Berg 1990 forHerder'sambiguitiesregardingthe equalityof peoples).

Herder's account of world history,conveyedin his sprawlingand encyclopedic

Ideen zur Philosophicder Geschichteder Menschheit,

tellsof the emergenceand disand decline,theirmigraappearance of different

peoples, theirculturalflourishing

tionsand adaptationsto local habitat,and theirmutualdisplacement,

conquest,and

First,each

subjugation.Each of these peoples was definedby threecharacteristics.

formsa community

held togetherby close ties among its members(cf. 1968:407),or,

in the wordsof the founderof romanticpoliticaltheoryAdam Miiller,a "Volksgemeinschaft."Secondly,each people has a consciousnessof itself,an identitybased

on a sense of shareddestinyand historicalcontinuity(1968:325). And finally,each

people is endowedwithits own cultureand languagethatdefinea unique worldview,

the "Genius eines Volkes" in Herderianlanguage(cf. 1968:234).

In brief,accordingto Herder'ssocial ontology,the world is made up of peoples

each distinguished

solidarity

by a unique culture(1), held togetherby communitarian

units of

(2), and bound by shared identity(3). They thus formthe self-evident

- themostmeaningful

observationand analysis(4) foranyhistoricalor social inquiry

way of subdividingthe populationof humans.In this ontology,ethnicgroupsand

culturesare anythingbut static- we findample discussionof theculturalbloom and

declineof this or thatpeople, of ethnogenesisand "ethnoexitus"in Herder'swork.

Nor did Herderassume thatall individualswereequally and uniformly

attachedto

theirethniccommunitiesor thatthisattachmenthad some natural,biologicalbasis.

In otherwords,Herderis ill suitedto playtheroleof a strawman bearingintellectual

for the "naturalization,""essentialization,"and "ahistoricism"that

responsibility

self-declared"constructivists"

deplore among their"primordialist"opponents.The

below.

problemswithHerderianontologylie elsewhere,as we will see further

Herder'sHeritage

But I should firstdiscuss Herder'sheritage,whichhas leftits marknot only on his

directdescendantsin folklorestudiesand culturalanthropology

(Berg 1990; Wimmer

1996), but also on sociologyand history.While the rise and global spread of the

nation-statehas changedthe terminology

thatwe use today,differentiating

Herder's

"peoples" into "nations" if statehoodwas achieved and "ethnicgroups" if it was

not, much of his social ontologyhas survived.This also holds true for empirical

researchon immigration,

as thissectionwill show,thoughobviouslynot equally for

all nationalresearchtraditions,theoreticalapproaches,or methodologicalcamps.

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGEAND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING

APPROACH

247

ethnicpeoples,forexample,

has until

Dividingup theFrenchnationintodistinct

beenanathemato mainstream

research

there(cf.Meillassoux1980;Le Bras

recently

in thetradition

of rationalchoicetheory(cf.Esser 1980)

1998).Scholarsworking

or classicalMarxism(Castlesand Kosack 1973;Steinberg

much

1981)are certainly

lessinclinedto acceptHerderian

thanthoseinfluenced

ontology

bythephilosophy

of multiculturalism.

variable-based

researchthattakesindividuals

as

Quantitative,

unitsof analysisavoidsmanyof thepitfallsof community

studies,and so forth.

- forbetteror forworse

- to

In the following

review,I will limitthe discussion

NorthAmericanintellectual

whichare a sourceof inspiration

to many

currents,

and to threesets of approaches:various

discussionsin othernationalcontexts,

strandsof assimilation

and ethnicstudies.As we willsee,

multiculturalism,

theory,

theseparadigmsrelyon Herderianontologyto different

degreesand emphasize

elements

oftheHerderian

ofethniccommunity,

different

and identity.

culture,

trinity

intakingethnicgroupsas self-evident

unitsofanalysisand

however,

Theyall concur,

- rather

thatdividing

an immigrant

observation,

assuming

societyalongethniclines

thanclass,religion,

and so forth is themostadequatewayof advancing

empirical

of immigrant

incorporation.

understanding

is mostvisiblein classicassimilation

whichstudiedhow

Herder'sontology

theory,

movedalonga one-way

roadinto"themainstream"

ethniccommunities

different

intothewhite,

Protestant,

eventually

assimilating

Anglophone-American

people.Asinto this"mainstream"

entailedthe dissolutionof ethniccommunities

similation

and spatialdispersion,

the dilutionof immigrant

cultures

throughintermarriage

of ethnicidentities

and thegradualdiminution

through

processesof acculturation,

waswhathasbeenfamously

called"symbolic

untilall thatremained

(Gans

ethnicity"

mostpowerful

and preciseaccountof

1979).In whatamountsto theintellectually

Gordonstatedthatthe disappearance

of ethnicculture("acassimilation

theory,

firstof ethniccommunity

and solidarity

wouldlead to thedissolution

culturation")

and finally

ofseparateethnicidentities

(Gordon1964).By

("structural

assimilation")

thattheywerecharacterized

by assuming

takingethnicgroupsas unitsof analysis,

and sharedidentities,

and by juxtaclosed social networks,

by distinctcultures,

- the "people"intowhich

nationalmainstream

posingthemto an undifferentiated

- Gordonobviously

dissolve

within

theseother"peoples"wouldeventually

thought

framework

a Herderian

(cf.thesympathetic

critiqueofAlba and Nee 1997:830f.).

versionsof theassimilation

paradigmhaverevisedmanyof GorContemporary

mostimportantly,

thatall

don'sassumptions

(cf.Brubaker2004:Ch.5), including,

and thatsocialacceptancedepends

roadsshouldand willlead to themainstream

In RichardAlba and VictorNee's reformainlyon previousculturalassimilation.

assimilation

an individual-level

mulation

of Gordon'stheory,

processis moreclearly

fromethnic-group-level

processes(Alba and Nee 1997:835),and updistinguished

dimension

of assimilation"

as a "socioeconomic

wardsocial mobility

replacesthe

closurecharacteristic

of Gordon's

withcultureand communitarian

preoccupation

and explanatory

This adds considerable

complexity

powerto theintellecwritings.

tualenterprise.

of Herder'sontologyin how individual-level

Still,we findremnants

processes

ethniccommunities

assimilation

as differentiating

areconceived:

pathsofdifferent

of peasantsvs. professionals,

vs. labormigrants,

and

ratherthanchildren

refugees

research

on spatialdispersion

crafted

so forth.

Thus,in superbly

(Alba and Logan

statistical

mod(Alba and Logan 1992),individual-level

1993)and homeownership

foreach ethnicminority

are calculatedseparately

els of assimilation

group,without

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

248

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

showingthat this subsamplingstrategybest fitsthe data. Differencesin the magnitudeof individual-level

variablesare thenmeant to indicategroup-levelprocesses

suchas ethnicdiscrimination

(Alba and Logan 1993:1394).In anotherpaper on intermarriagerates betweenethnicgroups (Alba and Golden 1986), no individual-level

controlsare introduced,thusassuming,forexample,thata womanof Polishancestry

- rather

who marriesa man of Polish ancestrydoes so because of ethnichomophily

than sharedlocality,occupation,or otheropportunity

structureeffects.

"Segmentedassimilationtheory"(Portesand Zhou 1993) envisionstwo outcomes

in additionto the standardassimilationpath describedby Gordon. In the enclave

mode of immigrant

incorporation,exemplified

by the Cuban communityin Miami,

ethnicgroupsmay persistover timeand allow individualsto achieveupwardsocial

mobilitywithinan ethnicenclaveeconomywithouthavingto developsocial tieswith

withouthavingto acculturateto themainstream,

and withouteventumainstreamers,

withthe nationalmajority.When immigrants

followthe "downward

ally identifying

assimilation"path, such as Haitians in Miami or Mexican immigrantsin Central

California,theydevelop social ties with,identifywith,and acculturateto the black

segmentof Americansocietyor withdowntroddenand impoverishedcommunities

of earlierimmigrant

waves,ratherthan the "whitemainstream."

Whichof thesemodes of incorporationwill prevaildependson government

reception of a community,

the discrimination

it encounters,and "most important,"the

degreeof internalsolidarityit can muster(1993:85-87). As this shortcharacterization makes clear,the basic analyticalschemeof "old" assimilationtheoryis again

maintained:despite occasional attentionto within-group

variation(1993:88f, 92),

ethnicgroupsconceivedas Herderianwholes move along the threepossible paths

of assimilation,choosing a pathwaydependingon degreesof solidarity(1993:88f,

92; Portes and Rumbaut 2001) or the specificcharacterof ethniccultures(Zhou

1997).2 It is alwaysassumed,in otherwords,ratherthan empiricallydemonstrated,

thatculturaldifference

and networksof solidarityclusteralong ethniclines.

Assimilationtheory'snemesis, multiculturalism

or "retentionism"in Herbert

Gans's (1997) terms,leads back to full-blownHerderianism.In contrastto the various strandsof neoassimilationtheorydiscussedabove,in whichethnicculturesrarely

assumecenter-stage

of theexplanatoryendeavor,3multiculturalism

assumesthateach

ethnicgroup is endowedwitha unique universeof normsand culturalpreferences

and thattheseculturesremainlargelyunaffected

by upwardsocial mobilityor spatial

dispersion.Thus, such perduringethnicculturesand communitiesneed to be recognized publiclyin orderto allow minorityindividualsto live theirlivesin accordance

withgroup-specific

ideas about the good lifeand thusenjoyone of the basic human

rightsthata liberal,democraticstateshould guarantee.

Will Kymlicka'smost recentbook is an example of superbscholarshipfromthis

multiculturalist

tradition(Kymlicka2007). The book offersa carefulanalysis of

the specifichistoricalconditionsunderwhichliberalmulticulturalism

emergedas a

major political paradigmin northwestern

Europe and North America. Somewhat

however,its authorends up advocatingthe propagationof liberalmulsurprisingly,

ticulturalism

across the restof the globe,regardlessof whethertheseconditionshave

been met. I have shownelsewhere(Wimmer2008b) thatthis contradictionemerges

because the analysisis bound by a Herderianontology:Kymlicka'sworldis made of

2For a moredifferentiated

analysisalong the same lines,see especiallyPortes(1995).

3But see

(1992), Zhou (1997) and the critiquesof Steinberg(1981) and Castles

Hoffmann-Nowotny

(1994).

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGEAND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING

APPROACH

249

state-bound

societiescomposedof ethnicgroups,each of whichis endowedwithits

owncultureand naturally

inclined

to in-group

solidarity.

Majoritygroupsdominate

and thusviolatetheirbasicculturaland politicalrights.

minorities

Suchviolationof

conflict

thegranting

ofsuchrights

reduces

while,

minority

rights

produces

conversely,

conflicts.

Seenfromthispointof view,globalizing

multicultural

policiesare indeed

theorderof thedaydespiteall thedifficulties

thatthisprojectencounters

because

in thefirstchaptersof thebook are rarelymet.

theenablingconditions

identified

To putthisin morepolemicalterms,

theHerderian

shieldsWillKymlicka's

ontology

normative

ofhisowncomparative

positionsfromtheinsights

empirical

analysis.4

A similarly

Herderianism

dominatesmuchof ethnicstudiesat

straightforward

and beyond.Withoutassuming

thegivenness

American

universities

and unambiguof theintegrity

and coherence

of ethniccultures,

and of the

ityof ethnicidentity,

of constituting

of ethniccommunities,

theveryprinciple

"AsianAmerisolidarity

and "African-American

"Native-American

"ChicanoStudies,"

can Studies,"

Studies,"

each focusedon a clearlyidentifiable

Studies"as separatesocialsciencedisciplines

Thevariousethnicstudiesdepartments

thus

objectofanalysiswouldbe questionable.

left-Herderian

tradition

continuewhatcouldbe calledan emancipatory,

developed

of recently

foundednation-states

in 19thand folklore

departments

by thehistory

theirpeople'sstruggle

againsttheoppression

by

century

Europe,whichdocumented

fromtheyokeof foreign

rule.5

ethnicothersand theireventualliberation

Ethnicstudiesinsistthatsocialclosureand discrimination

alongethniclinesare

- in contrastto the classicassimilation

societies

of immigrant

features

permanent

stageon theroad to the

paradigmthatconceivesof suchclosureas a temporary

natureof thisparadigmby disthe(left-)Herderian

Let me illustrate

mainstream.

an articlebyone of itsmostrenowned

proponents.

cussingbriefly

fromtheglobalSouthand

Bonilla-Silva

arguesthathighlevelsof immigration

the new,less overtformsof racismthathave emergedin the wake of the civil

thathad longcharacterthebiracialsocialstructure

are changing

movement

rights

in thefaceof this

In orderto maintain"whitesupremacy"

ized Americansociety.

racial

racialgroupto buffer

whites"(1) createan intermediate

threefold

challenge,

intothewhiteracialstrata,and (3) incorporate

conflict,

(2) allowsomenewcomers

blackstrata"(Bonilla-Silva

intothecollective

mostimmigrants

2004:934).The units

ethniccommuare individual

thatare sortedintothesethreenewracialcategories

and Hmong.To supportthisclaim

Vietnamese,

Brazilians,

nities,suchas Japanese,

whichhe aggregates

dataon individual

usessurvey

Bonilla-Silva

income,

empirically,

- a ranking

to

their

then

ranks

and

ethnic

(2004:935)

average

according

group

by

determined

and exclusively

thatis supposedto be entirely

by thedegreesof racism

in

Thiskindofanalysisthuspresupposes

at thehandsofthewhitemajority.

suffered

- thatthesocialworldis made

- ratherthenempirically

axiomaticfashion

showing

between

and discrimination

ofopposition

and therelations

up ofethniccommunities

see Loveman1997).6

them(fora moredetailedcritique,

4

along similarlines; see, e.g., Waldron(1995) and Sen

Many authorshave criticizedmulticulturalism

(1999).

5More

the oppressingpeople has become the object of a separatedisciplinetermed white

recently,

studies" (cf. Winddance,Twine,and Gallagher 2008). On the nationalistfoundationsof ethnicstudies,

see Espiritu(1999:511) and Telles and Ortiz (2008:Ch. 4). For a textbookportrayingU.S. societyas

a collectionof distinctpeoples all oppressedby the dominantwhitemajority,see Aguirreand Turner

(2007).

6U.S.

-styleethnicstudieshave had, forbetteror forworse,considerableimpacton the researchscene

in Europe,especiallyin Great Britain(as Banton 2003 recalls),thoughthe divisionof societyinto ethnic

different

and racial groupsis remarkably

(Irish and Jewishintellectualsclaimedthe statusof "racialized"

minoritiesas well,and the Muslimidentitydiscourseis muchmoredevelopedthan in the UnitedStates).

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

250

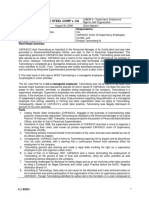

Figure1. A Herderianand a Barthianworld.

ThreeMoves BeyondHerderianApproach

The comparativeliteratureon ethnicityoffersat least threeinsightsthatsuggestthe

units of observationenproblematicnatureof takingethnicgroups as self-evident

and communitariansolidarity.None

dowed with a unique culture,shared identity,

research.Howof immigration

of theseinsightsis entirelyunknownto practitioners

ever,theircombinedsignificanceforthe studyof immigrantethnicityhas not been

scholarsin theirempiricalresearchpractice.It

sufficiently

recognizedby immigration

therefore

seemswarrantedto elaboratethesethreepointsmorefullyin the hope that

doing so will help establisha more sustainedconversationbetweenthe two fields.7

The NorwegiananthropologistFredrikBarth was firstto question Herder'sassumptionthatethnicgroupsare necessarilycharacterizedby a sharedculture(Barth

1969; but see Boas 1928). The two graphs in Figure 1 help to illustrateBarth's

approach. The leftgraph representsthe Herderianview,accordingto whichethnic

This landscape is here rendered

groupsreflectthe landscape of culturaldifference.

in terms

and differences

similarities

in three-dimensional

space, perhapsrepresenting

of language(the x-axis),degreesof religiosity

(the y-axis),and genderrelations(the

z-axis),such thatindividualswiththemost similarpracticesare situatedclose to one

on thislandscape of

other.Ethnicgroupsin a Herderiansocial worldmap faithfully

and difference.

culturalsimilarity

However,Barth and his fellowauthors showed in a widelycited collection of

ethnographicessays that in many cases across the world this is actually not the

case (see the graph to the right).Rather,ethnicdistinctionsresultfrommarking

observedby an

of the culturaldifferences

and maintaininga boundaryirrespective

outside anthropologist.Barth's boundaryapproach thus implieda paradigm shift

in the anthropologicalstudyof ethnicity:researcherswould no longer study"the

culture"of ethnicgroupA or B, but ratherhow theethnicboundarybetweenA and

B was inscribedonto a landscape of continuousculturaltransitions.Conformingly,

the definitionof ethnicitychanged: it no longerwas synonymouswith objectively

definedcultures,but ratherreferredto the subjectiveways that actors established

7For

see

scholarshipto the comparativeethnicityliterature,

previousattemptsto connectimmigration

Nagel (1994), who reliesheavilyon Barth,as well as Alba and Nee (1997:837-841),who discussShibutani

not givenbirth

These attemptshave unfortunately

and Kwan's book on comparativeethnicstratification.

to a sustainedconversationbetweenthesetwo researchtraditions.

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

251

^ Hakka <=>Holo, "Aborigines^

yfromIreland<=>FromNorthernIreland^

v Islanders Mainlandersy

^Taiwanese o OtherChinese^

^Italians, LatinAmericans o Irish^

yChinese American OtherAsian Americans^

V Catholics o Protestants,Jews^

<=>

<=>

=>

vJHispanics Asian Americans AfricanAmericans Anglo-Americans^y

^Mexicans

<=>Other Hispanics"^

Americans Other nations

Oaxaque-os <=>OtherMexicans

.^'

'Indigenous <=>Mestizos

'Zapotecos <=>Other Indigenous

in the United States.

Figure2. A Moermanianview on "race" and ethnicity

themfromethnic

groupboundariesby pointingto specificmarkersthatdistinguished

others.

Anotherbranchof anthropologicalthinking,startingfromMoerman (1965) and

leadingto the so-calledsituationalistschool (Nagata 1974; Okamura 1981), demonstratedthatethnicidentitiesmay be of a relationalnatureand producea hierarchy

of nested segments,ratherthan distinctgroups with clear-cut,mutuallyexclusive

collectiveidentities.8Let me illustratethis point with a U.S. example. The standard, racializedschemethatmuchof mainstreamsocial scienceroutinelyreproduces

in its researchpractice(Martin and Yeung 2003) conceivesof four "races" as the

main buildingblocks of Americansociety:whites,AfricanAmericans,Asians, and

pictureemerges.

Hispanics. Seen throughMoermanian lenses,however,a different

Figure 2 (inspiredby Jenkins1994:41) representsthe range of possible categories

withwhichan "Asian," "white,"and "Hispanic" personmightbe associated,either

or classificationby others.

throughidentification

The "Asian" person hails fromTaiwan and would perhapshighlighther identity

as a Hakka speaker(one of the Taiwanese dialects) when visitinga household of

Holo speakers.Both Hakkas and Holos mightbe groupedtogetheras "islanders"

when meetinga Mandarin speakerfroma familywho came to Taiwan after1948.

All of them,however,mightdistancethemselvesfromthe "freshoffthe boat" immigrantsfrommainland China (Kibria 2002). Mainland Chinese and Taiwanese

perhaps would be treatedas and see themselvesas Asian when encounteringan

AfricanAmerican.The same contextualdifferentiation

operatesfora personof Irish

for

and

a

Waters

1990:52-58)

Zapoteco fromthe centralvalleyof

origin(compare

Oaxaca (cf. in generalKearney 1996), as Figure2 illustrates.

leads to a twofoldrevision

This nestedcharacterof systemsof ethnicclassification

of Herder'sontology.First,not all ethniccategoriescorrespondto social groupsheld

- the leitmotifof Brubaker's(2004) aptly

togetherby dense networksof solidarity

- such as the

titledbook, EthnicityWithoutGroups.Some higherlevel categories

two

to

"Asians"

or

of

examples- mightbe

"Hispanics," give

pan-ethniccategories

8See also Keyes (1976), Cohen (1978), Burgess(1983), Okamura (1981), Nagel (1994:155f.),Jenkins

(1997:41), Okamoto (2003), and Brubaker(2004:Ch. 2).

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

252

relevantforpolitics(Padilla 1986;Nagel 1994; Espiritu1992),but not fortheconduct

of everydaylife (Kibria 2002), such as findinga job, a house, or a spouse. Put in

Weberianterms,thedegreeof social closurealong ethniclinesvariesacrosscontexts.

are not

levels of differentiation

Second, because categoriessituatedon different

categoriesare responsible

mutuallyexclusive,it is not alwaysclearwhetherlower-level

for higher-leveleffects.When we find, for example, that the social networksof

Hispanics are mainlycomposed of otherHispanics,we don't know whetherthis is

or of Oaxaquenos

an artifactof Mexican,Guatemaltecan,and Honduranhomophily,

to relateto otherZapotecos, or

befriending

Oaxaquenos, or of Zapotecos preferring

families(compare Kao and

even homophilyon the level of villagesor interrelated

Joyner2004; Gerhard,Nauck, and Kohlmann 1999).

A thirdand relatedpointthatcomparativeresearchhas broughtto light(especially

Richard Jenkins1997) is that individualsmightdisagreeabout whichare the most

relevantand meaningfulethniccategories.For example,one mightself-identify

primarilyas TaiwaneseAmerican,whilemainstreamAnglostendto lumpall individuals

of East Asian descentinto the category"Asian" (cf. Kibria 2002). More generally

agreedupon.

speaking,ethniccategoriesmightbe contestedratherthan universally

Such contestationis part of a broader politico-symbolic

struggleover power and

prestige,the legitimacyof certainformsof exclusionover others,and the meritsof

foror againstcertaintypesof people (forelaborationsof this Bourdiscriminating

dieusiantheme,see Brubaker2004:Ch. 1; Loveman 1997; Wacquant 1997; Wimmer

1995).

AgainstRadical Constructivism

In summary,the comparativeliteratureon ethnicityalertsus to the possibilitythat

membersof an ethnicgroup mightnot share a specificculture(even if theymark

theboundarywithcertainculturaldiacritica),mightnot privilegeeach otherin their

everydaynetworkingpracticeand thus not forma "community,"and mightnot

agree on the relevanceof ethniccategoriesand thus not carrya common identity.

To be sure, this threefoldrevisionof the Herderiannotion of ethnicitydoes not

implythatethniccategoriesalwaysand necessarilycross-cutzones of sharedculture;

some ethniccategoriesdo correspondto communitiesof bounded social interaction,

and some ethniccategoriesare widelyagreed upon and the focus of unquestioned

identification

by theirmembers.9In otherwords,a Herderianworldmightverywell

be the outcomeof the classificatory

strugglesbetweenactors and become stabilized

and institutionalized

over time.Recent systematicreviewsof the comparativeliterature have revealedconsiderablevariationin degreesof communitariansolidarity

and homogeneityacross ethnicgroups

(or social closure), culturaldistinctiveness,

(Wimmer2008c).

Historicalresearchshows that the same holds trueforwithin-casevariationover

time:culturally"thin"(Barthian),segmentally

differentiated

(Moermanian),and contested (Bourdieusian) systemsof ethnic classificationmay transforminto culturand largelyagreed upon systemsa la Herder,and the

ally thick,undifferentiated,

otherway around. Compare the shiftto a Herderianworld broughtabout by the

9AfricanAmericansin the United States providean example of an ethnosomaticcategorythatcorrenetworksand therarityof exogamous

spondsto a boundedcommunity

(as dozens of studiesof friendship

marriages);forother,non-Europeanexamples,see Wimmer(2008).

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

253

of the "one drop" rule to determinewho belongedto a clear-cut

institutionalization

"black" categoryin the U.S. South, a shiftthaterased the varand undifferentiated

ious "mixed" categoriesthatpreviouslyhad existed(Lee 1993; Davis 1991). At the

same time,life became less Herderianfor others:forJews,Italians,and Irish who

managedto becomeacceptedas an ethnicsubcategoryof the "white"category(Saks

underwentsegmentary

differentiation

and new

1994; Ignatiev1995), whichtherefore

internalcontestation(how "mainstream"are Jewsand Catholics?). Similarly,Polish workersin the coal miningareas of Germanywere the object of a policy of

forcedassimilationand finallybecame part of the culturally"thick,"undifferentiated Herderiannationof Germans(Klessman 1978),whilea centurylater,Cold War

led to the segmentaldifferentiation

of that nation into

partitionand reunification

the quasi-ethniccategoriesof "Ossis" and "Wessis" (Glaeser 1999).

Given this variationacross cases and over time,it is problematicto take it for

societiesinto ethnicgroupscapturesone of its

grantedthata divisionof immigrant

fundamentalstructuralfeatures,or to assume communitarianclosure,culturaldisor sharedidentitywithoutactuallyshowingempiricallythatthe groups

tinctiveness,

fluin questiondisplaythesefeatures.It is equally problematic,however,to identify

and strategicmalleabilityas theverynatureof theethnic

idity,situationalvariability,

paradigm(e.g.,Nagel

phenomenonas such,as in radicalversionsof theconstructivist

as a cognitivescheme

1994) that treatethnicityas a mere "imaginedcommunity,"

of littleconsequenceto the lifechancesof individuals,or as one individual"identity

should be able to

choice" among manyothers.An adequate theoreticalframework

accountfortheemergenceof a varietyof ethnicforms,includingboth thosefavored

opposites.

by Herderiantheoriesand theirradical constructivist

HOW TO THINK ABOUT ETHNICITY: THE GROUP

FORMATION PARADIGM

Over the past decade or so, several new approaches have appeared in the social

and

sciencesthat are fullycompatiblewith the insightsgained by anthropologists

derive

from

the

most

I

have

now

summarized.

that

They

comparativesociologists

varied traditionsof thoughtand have littlein common except theirshared antiHerderianqualities,as the followingbriefoverviewwill illustrate.In the field of

normative-intellectual

debates, major exponentsof cultural studies (Gilroy 2000;

Bhabha 2007) recentlyhave proposed going beyond the "essentializing"discourse

and striveforwhat could be called a neohumanist,universalist

of multiculturalism

mode of philosophicalreflectionand social analysis.Other,more empiricallyand

orientedprojects,some derivingfromthe "new ethnicities"tradiethnographically

tion initiatedby StuartHall ([1989] 1996), some inspiredby the writingsof Pierre

constitutedfield

Bourdieu,seek to understandhow actors situatedin a historically

who

and

does not (Back

who

who

about

narratives

various

are,

belongs,

they

develop

al.

Brubaker

et

Anthias

2006;

2007).

1996;

in GerA more macro-sociologicaldevelopmentis the "Ethnisierungsansatz"

man sociology,whichoftenderivesinspirationfromgeneralsystemstheoristNiklas

Luhman. "Ethnicisation"is understoodas a self-reinforcing

process of defining,

thuscreating"miin

its

ethnic

social

and

dimension,

reality

reactingupon

shaping,

etc.

law

of

in

domains

the

enforcement,

education,

unemployment,

norityproblems"

In

another

also

Rath

see

Radtke

Bommes

context,

2003;

1999;

1991).

(Bukow 1992;

of imSteve Vertovec(2007) has recentlyobservedthe emerging"super-diversity"

of

and

socioeconomic

trajectories adaptationthat

positioning,

migrantbackgrounds,

makesa neat aggregationinto separateethniccommunitiesimpossible.Glick Schiller

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

254

et al. (2006) have urgedus to go "beyondthe ethniclens" and focusinsteadon innetworksand institutional

teractionalpatterns,includingcross-ethnic

arrangements

that develop dependingon where a localityis positionedin the global capitalist

order.

betweenthese

This is not themomentto discussthecommonalitiesand differences

various post-Herderianapproaches.Rather,I would like to introduceand dedicate

the rest of this articleto anotheremergingtraditionof thought,one that,among

this familyof approaches,distinguishesitselffromthe rest in termsof theoretical sophistication,analyticalprecision,and empiricalgrounding.It emergedfrom

Barth'sconcernwithethnicboundariesand conformingly

has been labeledtheethnic

the ethnicgroupformationperspective.

boundary-making

paradigmor,alternatively,

It can be characterizedby fourratherwell-knownaxiomaticassumptionsthatderive

fromthe various researchstrandssummarizedabove and are meant to replace the

Herderianontology.I summarizethem here as conciselyas possible,withoutany

claim to originality

or innovation.

First,ethnicgroupsare seen as the resultof a potentiallyreversiblesocial process

of boundary-making

units of observationand analysis

ratherthan as self-evident

(the constructivist

principle,as statedby Nagel 1994; Jenkins1997:Ch. 1; Brubaker

2004:Ch. 1). Secondly,actors mark ethnicboundarieswith culturaldiacriticathey

perceiveas relevant,such as languageor skincolor,and the like.These markersare

not equivalentto the sum of "objective"culturaldifferences

thatan outsideobserver

tradimay find (the subjectivist

principle,as developed in the Weberian/Barthian

tion). Third,ethnicgroups do not emergespontaneouslyfromthe social cohesion

betweenindividualsthat share cultureand origin,but fromacts of social distanccf.

ing and closurevis-a-vismembersof othercategories(the interactionist

principle',

the elaborationof thisWeberianthemeby Tilly 1998:Ch. 3). Finally,the boundary

perspectivedrawsour attentionto processesof groupmakingand everydayboundary work (the processualistprinciple),and puts less emphasis on the geometryof

group relations,as, forexample,in the U.S. and British"race relations"approach

(Niemonen 1997).

The boundary-making

approach has recentlygained some ground in migration

research.Richard Alba (2005), ChristopherBail (2008), Rainer Baubock (1998),

JoaneNagel (1994), Dina Okamoto (2006), RogerWaldinger(2003b,2007), Andreas

Wimmer(2002), and Ari Zolberg and Woon (1999) have used the boundary-making

in

language to reviewcentralissues of the field.While thereare many differences

theoreticalorientationamong theseauthors,and some quite substantialand explicit

betweenthem,theiranalysesnevertheless

disagreement

proceed along similarlines.

While it is too earlyto offera reviewof the substantiveempiricalresultsthat this

researchhas produced,we can highlightits main theoreticalpropositions,the way

thatit definestheproblematique

of immigration

research,and how thesepropositions

and problematiquesdifferfromthe four paradigms previouslydiscussed. This is

the task I set forthe remainderof this section.The subsequenttwo sectionsthen

go beyond this exerciseat theoreticalintegrationand synthesisby offeringsome

suggestionas to how this researchtraditioncould develop furtherby focusingon

both mechanismsof boundaryformationand those researchdesignsmost suitedto

studythem.

and Nationals

Making Immigrants

The boundary-making

approach problematizesthe distinctionon which the field

of immigrationresearchis based: that betweenimmigrantminoritiesand national

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

255

approach implies

majorities.It does so in threeways. First,the boundary-making

that ethnicitydoes not emergebecause "minorities"maintaina separate identity,

culture,and communityfromnational "majorities,"as Herderiantheoriesimply.

Rather,both minoritiesand majoritiesare made by definingthe boundariesbetween

research

them.The German"nation"or the "mainstream"of Americanimmigration

as much the consequencesof such boundary-making

is therefore

processesas are

"ethnicminorities"(cf. Williams1989; Verdery1994; Wimmer2002; Favell 2007).

Second, a comparativeperspectiveforcesitselfon the observerbecause it becomes

and nationalsdisplaysvaryingpropobvious thatthe boundarybetweenimmigrants

erties,as illustratedby the varyingdefinitionsof "immigrants"in nationalstatistics

(cf. Favell 2003) and the correspondingobstacles to findingcomparabledata for

imcross-nationalresearch(HofTmeyer-Zlotnik

2003). Third-and fourth-generation

as long as

migrantscount as "ethnicminorities"in the eyes of Dutch government,

theyare not "fullyintegrated";theydisappear fromthe screenof officialstatistics

and thusalso largelyfromsocial scienceanalysisin France;and in theUnitedStates,

theyare sortedinto categoriesdependingon the color of theirskin,as will be their

Recentsurveyresearchhas shownsubstantialvariation

childrenand grandchildren.

in various

in the nature(and distinctness)of boundariesdrawnagainstimmigrants

European countries(Bail 2008)- a variationnot necessarilyin tune with that of

officialstatisticalcategories,to be sure,because government

agenciesand individual

citizensmightdisagreeas to whichethniccategoriesshould be consideredrelevant

and meaningful.

The distinctionbetweenimmigrantsand nationals varies because it is part and

definitionsof where the boundaries of the nation are drawn.

parcel of different

is an ongoing

These definitions

may also change over timebecause nation-building

of

processfullof revisionsand reversals,as is illustratedby the recentintroduction

laws in manycountries,theabandonmentof whitepreference

dual nationality

policies

in U.S., Canadian, and Australianimmigration

law, or the recentshiftto a partial

ius sanguinisin Germany(cf. the ratheroptimisticassessmentof such changes by

the divisionbetween

therefore,

perspective,

Joppke2005). From a boundary-making

nationalsand immigrants,

includingsocial science researchon how the divisionis

(or should be) overcomethrough"assimilation"(in the UnitedStates),"integration"

and

(in Europe), or "absorption"(in Israel) is a crucial elementof nation-building

needs to be studiedratherthantakenforgrantedifwe are to adequatelyunderstand

the dynamicsof immigrantincorporation(Favell 2003; Wimmerand Glick Schiller

2002).

distincthe immigrant-national

This leads us to the thirdway of problematizing

tion. While migrationappears froma demographicperspectiveas a straightforward

issue (individuals"moving"acrosscountryborders),the boundary-making

approach

revealsthe politicalcharacterof thisprocess."Immigration"only emergesas a distinct object of social science analysis and a political problem to be "managed"

once a state apparatus assigns individualspassportsand thus membershipin national communities(Torpey 1999), polices the territorialboundaries,and has the

administrative

capacityto distinguishbetweendesirableand undesirableimmigrants

(Wimmer1998). Assimilationtheory,both old and new, as well as multiculturalof the

ism, do not ask about this political genesisand subsequenttransfiguration

social

world

too

feature

of

the

a

it

as

but

take

distinction,

given

immigrant-national

obvious to need any explanation(cf. the critiqueby Waldinger2003a). Thus, the

social forcesthatproducethe veryphenomenonthatmigrationresearchis studying

and thatgive it a specific,distinctformin each societyvanishfromsight.

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

256

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

Distancing,

Making NationalsOut of Immigrants:

BoundaryShifting,

and SelectiveCulturalAdoption

is treatedas the productof a

Once thedistinctionbetweennationalsand immigrants

of

a

new

nation

perspectiveon theold questions

historically

specificprocess

building,

of immigrant"assimilation"and "integration"arises.Ari Zolberg and Woon (1999)

as well as Richard Alba and Nee (2003) were the firstto redefineassimilation

definedas aliens or

as a process of boundaryshifting:groups that were formerly

now

full

of

the

nation. This again

minorities"

are

treated

as

members

"immigrant

is a contestedprocess- the resultof a power-driven

political struggle(Waldinger

and

2003b)- ratherthan the quasi-naturaloutcomeof decreasingculturaldifference

social distance.

Followingthe interactionist

principlepreviouslydiscussed,boundaryshiftingdethe

on

pends

acceptanceby

majoritypopulation,as this majorityhas a privileged

to

the

state

and, thus,the power to police the bordersof the nation.

relationship

therefore

needs to overcomeexistingmodes of social closurethat

Boundaryshifting

the boundariesbetween

have denied membershipstatusto outsidersand reinforced

and

minorities.

assumes

that

such

Assimilation

majorities

acceptanceis depentheory

of "them"becoming

dent on degreesof culturalassimilationand social interaction,

and behavinglike "us." It thus tends to overlook the social closure that defines

who is "us" and who is "them" in the firstplace. The left-Herderian

approach,

by contrast,overstatesthe degree and ubiquityof such closure by assumingthat

discrimination

is necessarilyand universallythe definingfeatureof ethnicrelations.

The boundary-making

perspectiveallows us to overcomeboth of these limitations

the

by examining processesof social closureand openingthat determinewherethe

boundariesof belongingare drawnin the social landscape.

Let me brieflyillustratethe fruitfulness

of this approach by reviewingsome wellknownaspectsof U.S. immigration

history,as well as some less well-knownfeatures

of Europe'simmigration

in the 19th-and 20th-century

scenetoday.Boundaryshifting

United States proceeded along different

lines, dependingon whetherimmigrants

were treatedas potentialmembersof a nation defined,up to World War I, as

consistingof white,Protestantpeoples of European descentstandingin opposition

to descendantsof Africanslaves (cf. Kaufmann2004). While British,Scandinavian,

and German immigrantsthus were accepted and crossed the boundary into the

mainstream

on culturalassimilationand social associationalone,southern

contingent

Irish

Catholics,and easternEuropean Jewshad to do more

European Catholics,

work

to

achieve

the same. They were originallyclassifiedand treated

boundary

as not quite "white" enough to be dignifiedwith full membershipstatus.Italians

(Orsi 1992), Jews(Saks 1994), and Irish (Ignatiev1995) thus struggledto dissociate

themselvesfromAfricanAmericans,so as to provethemselvesworthyof acceptance

into the nationalmainstream.

Similarprocessescan be observedin laterperiods.Loewen providesa fascinating

account of how Chinese immigrantsin the MississippiDelta, who were originally

assigned to, and treatedas membersof, the "colored" caste, managed to cross

the boundaryand become an acceptablenonblack ethnicgroup admittedto white

schools and neighborhoods(Loewen 1971). They did so by severingexistingties

with black clientsand by expellingfromthe communitythose Chinese who had

marriedblacks. In other words,they reproducedthe racial lines of closure that

are constitutiveof the Americandefinitionof the nation. Similarly,contemporary

middle-classimmigrants

fromthe Caribbean and theirchildrenstruggleto distance

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

257

themselvesfromthe African-American

communityin orderto provetheirworthin

the eyes of the majorityand therebyavoid associationwiththe stigmaof blackness

(Waters1999; Woldemikael1989).

fromtheguest-worker

In contemporary

continentalEurope,establishedimmigrants

period dissociate themselves,sometimeseven more vehementlythan autochthons,

fromthe recentlyarrivedrefugeesfromformerYugoslaviaand Turkeyby emphasizing exactlythose featuresof thesegroupsthatmustappear as scandalous fromthe

theirlack of decency,and

majority'spoint of view: their"laziness,"theirreligiosity,

theirinabilityto "fitin" establishedworking-classneighborhoods.Such discourses

are meantto maintainthe hard-won capital of "normalcy,"achievedat the end of

a long and painfulprocessof boundarycrossing,by avoidingbeing identifiedwith

these"unacceptable"foreigners

(Wimmer2004; similarlyforLondon Wallman 1978;

Back 1996).

In these strugglesover the boundariesof acceptanceand rejection,culturedoes

theone foreseenin classicalassimilationtheory,

indeedplaya role,butnot necessarily

or ethnicstudies.Immigrantswho struggleto gain the acceptance

multiculturalism,

necessaryfor crossingthe boundaryinto "the mainstream"may aim at selectively

acquiringthose traitsthat signal fullmembership.What these diacriticaare varies

fromcontextto context(cf. Zolberg and Woon 1999; Alba 2005). In the United

States,stickingto one's religionand ethnicityis an accepted featureof becoming

national,whileprovingone's distancefromthe commandsof God and the loyalty

of one's co-ethnicsis necessaryin many European societies.The requirementsof

"language assimilation"also vary,even if the general rule is that the betterone

speaks the "national" language the easier it is to be accepted (Esser 2006). While

speakingwith thickaccents and bad grammaris acceptablefor manyjobs in the

UnitedStates,as long as the languagespokenis meantto be English,it is muchless

forms

toleratedin Franceor Denmark.The variation,again,is explainedby different

thatpinpointcertainculturalfeaturesas boundary

of nation-building

and trajectories

markersratherthan others(Zolberg and Woon 1999). The ethnicgroup formation

the selectiveand varyingnatureof culturaladoption and

perspectivethushighlights

emphasizesthe role thatculturalmarkersplay in signalinggroupmembership.

By contrast,classic assimilationtheory(and some strandsof neo-assimilationism)

takes the culturalhomogeneityof "the nation" for granted,even if this culture

is nowadays thoughtof as the syncretistic

product of previouswaves of assimilation (cf. Alba and Nee 1997). It assumes this national majority'spoint of view

in order to observe how individualsfrom"other nations,"endowed with different cultures,are graduallyabsorbed into "the mainstream"througha process of

becoming similar (Wimmer 1996; Waldinger2003a). Those who do not become

similar remain "unassimilated"and coalesce in ethnic enclaves or descend into

contested,

the urban underclass("segmentedassimilation").Thus, the power-driven,

selectivenature of processes of culturaladoption vanishes from

and strategically

sight.

Ethnic studies,on the other hand, oftenemphasize that the dominated,racialized "peoples" develop a "cultureof resistance"againstthe dominating,racializing

and

"people." This emphasisoverlooksthat the dominatedsometimesstrategically

miother

with

to

in

order

markers

cultural

disidentify

boundary

adopt

successfully

noritiesor theirown ethniccategoryand gain acceptanceby the "majority,"as the

in Europe illustrate.

immigrants

examplesof the MississippiChineseor guest-worker

In conclusion,we can gain considerableanalyticalleverageif we conceiveof immigrantincorporationas the outcomeof a struggleoverthe boundariesof inclusion

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

258

in whichall membersof a societyare involved,includinginstitutionalactors such

as civil society organizations,various state agencies,and so on. By focusingon

these struggles,the ethnicgroup formationparadigmhelps to avoid the Herderian

ontology,in whichethniccommunitiesappear as the givenbuildingblocks of society,ratherthan as the outcome of specificsocial processesin need of comparative

explanation.

MECHANISMS AND FACTORS: TOWARD AN

EXPLANATORY ACCOUNT

But how are we to explain the varyingoutcomesof these struggles?What are the

mechanismsof boundaryformationand dissolution?To the best of my knowledge,

thereis no theoryor model that gives a satisfactoryanswer to these questions.

In what follows,I would like to go beyond the synthesisof general theoretical

outlinedin theprevioussectionand further

propositionsand researchproblematiques

mechanismsand factorsthat might

advance the boundaryapproach by identifying

help develop a genuinelycausal and comparativeaccount. I will do so by relying

that I have

fieldtheoreticmodel of ethnicboundary-making

on an institutionalist,

recentlyproposed(Wimmer2008c).

This approach suggestslookingat threeelementsthat structurethe struggleover

boundaries,influencingthe outcomes of these strugglesin systematicways. First,

sense of the term)provideininstitutionalrules (in the broad, neo-institutionalist

centivesto pursue certaintypesof boundary-making

strategiesratherthan others.

Secondly,the distributionof power betweenvarious participantsin these struggles

influencestheircapacityto shape the outcome,to have theirmode of categorization

respectedif not accepted,to make theirstrategiesof social closureconsequentialfor

others,and to gain recognitionof and for theiridentity.Networksof politicalalliancesare a thirdimportantelementbecause we expectethnicboundariesto follow

the contoursof social networks.I now will illustratethis field-theoretic

approach

in

by showinghow thesethreefactorsinfluencethe dynamicsof boundary-making

urban labor markets.

Institutions

The boundary-making

consequencesof labor marketregimesrecentlyhave received

considerableattention(e.g., Kogan 2006). It has become clear that the boundaries

against immigrantlabor are weaker in liberal welfarestates with "flexible"labor

marketsand therefore

a strongerdemandforunskilledlabor,confirming

thatstrong

welfarestate institutionsproduce less permeableboundaries against nonnational

others(Freeman 1986). From an ethnicgroupformationperspective,

thisis because

the class solidarityunderlying

welfarestatesdepends on a nationalistcompact that

induces high degrees of social closure along national lines (Wimmer 1998). The

welfarestatetendsto come at the priceof shuttingthe doors to outsiderswho have

not contributedto the makingof the social contractand who thus should not be

allowed to enjoyits fruits.

At thesame time,welfarestatesallow immigrants

to say no to jobs theyare forced

to take in "liberal" societies,whichfollowa "sink-or-swim"

policy regardingimmiThis difference

both explainswhywe findless immigrant

granteconomicintegration.

in such societiesand generatesthe hypothesisthatimmigrants

entrepreneurship

rely

less on ethnicnetworkswhen findinga job or employingothersthan theywould

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

259

in "liberal" labor markets(Kloosterman2000). Ethnic networksand welfarestate

as arguedby Congleton(1995).

servicesmightwell be substitutes,

Anotherimportantfeatureof labor marketregimesare the rules for accepting

foreigncredentials.These rules produce a ratherdramaticboundarybetweenhome

bornand foreignborn,as well as betweenmembersof OECD countries,who tendto

recognizeone another'sdiploma and professionalcredentialsat least partly,and the

restof theworld.The selectiverecognition

of educationaltitlesand job experiencesis

a major mechanismthataffectsimmigrants'

earnings(Friedberg2000; Bratsbergand

whichlabor marketsegmentsare open to them.From a

Ragan 2002) and determines

thisis not so much a consequenceof an information

boundary-making

perspective,

cost problemthatemployersface whenevaluatingforeigncredentials,as economists

would have it (cf. Spencer 1973), but rathera primemechanismof social closure

of being treatedpreferentially

on

throughwhichnationalsmaintaintheirbirthright

- even at quite dramaticcosts forthe economyas a

of "their"country

the territory

whole,as economisthave argued(Spencer 1973).

There is also some researchon how rules and regulationsregardinghiringpractices influencethe relativeopennessor closureof particularlabor marketsegments.

The somewhatsurprisingresultof experimentalfieldstudiesis that the degree of

labor marketdiscrimination

against equally qualifiedimmigrantsseems not to be

laws and regulations(Taran et al.

anti-discrimination

influencedby country-specific

2004).

A side note on the issue of institutionaldiscriminationmight be appropriate

here. As many of the more methodologicallysophisticatedimmigrationscholars

have pointedout, we should resistautomaticallyattributing

unequal representation

in different

segmentsand hierarchicallevels of a labor marketto institutionalized

and closure(see the critiqueby Miles 1989:54fT.).

processesof ethnicdiscrimination

approach,

Accordingto the subjectivistprinciplecentralto the boundary-making

it is only meaningfulto speak of ethnic(as opposed to othertypesof) boundaries

of co-ethnicsover others.

whentheyresultfroman intentional

preference

In Germany'slabor market,to give an example,childrenof Turkishimmigrants

in the apprenticeship

are heavilyoverrepresented

systemand dramaticallyunderrepof highereducation.This distributional

resentedin the institutions

pattern,however,

resultsfromsortingall childrenof working-classparentage,independentof their

ethnicor nationalbackgroundor theircitizenshipstatus,into tracksleadingto apor otheron-the-jobtrainingprogramsearlyin theirschool career(Crul

prenticeships

and Vermeulen2003; Kristenand Granato 2007). Such institutionalsortingeffects

are obviouslynot ethnicin nature.10

The same can be said of the mechanismsthat lead Turkishadolescentsinto the

less demandingand rewardingon-the-jobtrainingprogramsand Germansinto the

tracks- claims to havingdiscoveredan institumore prestigiousfullapprenticeship

tionalizedethnicsortingpolicynotwithstanding

(Faist 1993). The main mechanism

seems again to be sortingbased on typesof schools attendedin the highlydifferentiatedGerman school system(Faist 1993:313). This is not to deny that ethnic

transitionor in hiringdeand closuredo existin the school-to-work

discrimination

in Germany,see

cisionsin general(fordirectevidencebased on real-lifeexperiments

Goldberget al. 1996). How muchtheydo, however,is a matterto be empirically

10Most coefficients

forethnicbackgroundvariablesin regressionson the achievementof a gymnasium

degreehave a positivesign once parentaleducationand occupationare controlledfor,as demonstrated

by Kristenand Granato (2007).

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

260

directly(Goldberg

investigated

throughmethodscapable of observingdiscrimination

et al. 1996), ratherthan simplybeing "read" offdistributional

outcomes,as is done

in the ethnicstudiestradition,or offthe significance

of ethnicbackgroundvariables

once individual-level

variablesare taken into account, as in much researchon the

"ethnicpenalty"in thelabor market(e.g., Heath 2007; Silbermanand Fournier2006;

Berthoud2000).

ResourceDistribution

and Inequality

The second step of analysis would examine the consequencesof immigrants'differentialendowmentwith economic,political,and culturalresources(cf. Nee and

Sanders 2001). A few researchershave analyzed the effectsof such resourcedistriwithlower

butionsfroma boundary-making

perspective.It seems that immigrants

educationalcapital and less economicresourcesare particularlylikelyto end up in

ethnicallydefinedniches in the labor market,while betterskilled immigrantsare

in Calmuchless dependenton such niches(see the case studyof Swiss immigrants

iforniaby Samson 2000). Furthermore,

migrantswho have been negativelyselected

on thebasis of theirlack of educationand professionalskills,such as thoserecruited

throughthe variousguest-worker

programsin Europe or the braceroprogramin the

United States,are particularlydisadvantagedin the labor markets,especiallywhen

it comes to translatingskillsinto occupation(Heath 2007). For thesemigrants,the

likelihoodof remainingtrappedin ethnicallydefinedlabor marketnichesis especially

high.

Despite these advances, it is strikinghow littleis known about how resource

in labor markets.As in

distributions

influenceprocessesof ethnicboundary-making

the analysisof labor marketregimes,we would again have to understandhow other

mechanismsthatare not relatedto the makingand unmakingof ethnicboundaries

influencethe labor markettrajectoriesof individuals.In otherwords,we would first

need to understandhow generalprocessesof class reproductionand mobilityaffect

of variouscapitals,as arguedand demonstrated

migrants'positionin thedistribution

in researchon Germanyby Kalter et al. (2007). Unfortunately,

I am not aware of

any studythathas takenthe class backgroundof migrantsin theircountryof origin

and thusthe social backgroundof second(as opposed to the countryof settlement)

of how

generationindividualsinto account. However,only a deeper understanding

the generalmechanismsof intergenerational

class reproductionaffectmigrantswill

allow us to tell whetherthe concentrationof certainimmigrantgroups in certain

professions,labor marketsegments,or occupational strata are the effectsof class

reproductionor the outcomeof boundary-making

processes.

Perhaps this argumentshould be illustratedwith an empirical example. Are

Mexican Americansin the United States and Portuguesein France remainingin

skilledworking-class

positions,as has been argued (Waldingerand Perlmann1997;

Tribalat 1995), because theypursuea strategyof ethnicniche developmentand defense,or because theyare sortedinto thesepositionstogetherwithotherindividuals

of a largelyrural and peasant backgroundby the mechanismsof class reproduction?Even some of the methodologically

most sophisticatedand analyticallycareful

researchinto the "ethnic penalty" in the labor marketassumes, perhaps following the authors' Herderianinstincts,that ethnicvariationmeans ethniccausation

ignoringthe potentialrole of class background(see again Heath 2007; Silberman

and Fournier2006; Berthoud2000).

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HERDER'S HERITAGE AND THE BOUNDARY-MAKING APPROACH

261

in the labor marketoftenjumps to Herderian

In general,researchon immigrants

conclusionswhen discoveringsignificantresultsfor ethnicbackgroundvariables

characteristics

thatmightbe uninsteadof looking forunobservedindividual-level

equally distributedacross ethniccategories(such as languagefacilityand networks;

thatmay covary

see Kalter 2006), forvariationin contextsand timingof settlement

channelsof migration

withethnicbackground,or fortheselectioneffectsof different

characteristics

are taken

(cf. Portes 1995). Even whensome of theseindividual-level

on group-levelethnicdifinto account,the discussionsometimesremainstransfixed

ferences.A good example is Berthoud'sotherwisesophisticatedresearchon ethnic

employment

penaltiesin Britain.Althoughethnicbackgroundaccounts fora mere

1.7 percentof the variationin employmentstatus (Berthoud2000:406), the entire

articleis organizedaround a comparisonof the labor marketexperiencesof white,

Indian, Caribbean,Pakistani,and Bangladeshimen.

Networks

I suggestto look at how

and resourcedistribution,

frameworks

Besides institutional

networksinfluencethe formationof ethnicboundariesin labor markets.We know

labor marketaccess (Lin 1999)

quite a bit about the role of networksin structuring

and especiallyin the processof ethnicnicheformation.Networkhiringcharacterizes

many for low skilled labor and explains why resource-poorimmigrantsare more

likelyto end up in such ethnicallydefinedniches(Waldingerand Lichter2003). Networkhiringis widespreadamong companiesthatrelyon labor intensiveproduction

methods,wherecredentialsand skills are less importantthan reliabilityand easy

integrationinto existingteams,and in labor marketswhereundocumentedworkers abound. On the otherhand, we also know that weak networkties,which are

oftenmultiethnicin nature,are importantfor betterskilled immigrants(Samson

2000; Bagchi 2001) employedin othersegmentsof the labor market,as a long line

of researchin the wake of Granovetter'scanonical articlehas shown (Granovetter

1973).

Despite these generalinsights,the preciseconditionsunder whichnetworkscoalesce along ethniclinesand produceethnicnichesstillremainsomewhatof a mystery.

As withprocessesof institutionalsortingand the effectsof resourceendowments,

mechanisms.

one needs to carefullydistinguishethnicfromotherboundary-making

or

of

be

the

networks

consequence family villagesolimight

Ethnicallyhomogenous

lines

ethnic

closure

social

rather

than

(cf. Nauck and Kohlmann1999).

along

darity,

The accumulationof such familyties does not automaticallylead- in an emerFamilynetworkhiringmay

genceeffectof sort- to ethnicsolidarityand community.

lead to the formationof a niche that only an outside observerwearing

therefore

Herderianglasses could then identifyas that occupied by an "ethnicgroup"- in

analogy to species occupyingcertainecological niches.In otherwords,even where

individualsof the same ethnicbackgroundclusterin similarjobs or sectorsof the

mechanisms

economy,we should not jump to the conclusionthatethnic-group-level

are responsibleforthispattern.

The final analyticalstep would consist in drawingthese threelines of inquiry

togetherand determininghow the interplaybetweeninstitutionalrules, resource

and networkingstrategiesdeterminethe specifictrajectoriesof immidistribution,

in labor marketsover time.An analysisthatproceedsalong these

individuals

grant

variation

and within-group

lineswould probablydiscovermuchmoreindividual-level

than a Herderianapproach thatfocuseson how "Mexican," "Turkish,"or "Swiss"

This content downloaded from 65.51.214.12 on Thu, 07 May 2015 05:47:19 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY

262

immigrantsfare in the labor marketor on which niche is occupied by which of

these"groups."Some Mexican familiesin the United States,endowedwithlow educational capital, embeddedin home-townnetworks,and affectedby weak welfare

stateinstitutions

seeking

mightindeedpursuea strategyof proletarianreproduction,

stable low skilledjobs that pay well over two or more generations.Others might

struggleto advance in the educationalsystemonly to discoverthe firmlimitsimtheyface

posed by the quality of schools theycan affordand the discrimination

endowed with

when seekingotherthan the least-qualifiedjobs. Other immigrants,

anothermix of resources,focusedon weavingpan-ethnicnetworks,and affectedby

otherinstitutional

rules such as affirmative

action hiring,mightexperiencean easy

transitionintotheprofessionalmiddleclass. Stillothersmightspecializein theethnic

businesssectorand draw upon a large networkof clientsfromwithinthe Mexican

community(see the heterogeneousoutcomesreportedin Telles and Ortiz 2008).

overindividuals,

are obviouslynot randomlydistributed

These different

trajectories

but need to be explainedas the combinedeffectsof fieldrules and theirchanges

over time;the individual'sinitialendowmentof economic and culturalcapital and

subsequentchanges in the volume and compositionof those formsof capital; and

the variablepositionof an individualin an evolvingnetworkof social relationships