Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On Guerrillas and Gangs and Sham Truce Talks in Latin American

Uploaded by

Jerry E. Brewer, Sr.0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views4 pagesA Merry-go-round of Deception in FARC and MS 13 Truces

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentA Merry-go-round of Deception in FARC and MS 13 Truces

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views4 pagesOn Guerrillas and Gangs and Sham Truce Talks in Latin American

Uploaded by

Jerry E. Brewer, Sr.A Merry-go-round of Deception in FARC and MS 13 Truces

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Home | Columns | Media Watch | Reports | Links | About/Contact

Column 072015 Brewer

Monday, July 20, 2015

On Guerrillas and Gangs and Sham Truce

Talks in Latin American

By Jerry Brewer

While truces have come and gone so frequently

between Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de

Colombia (FARC) guerrillas and the Colombian

government in Bogota, as well as the Mara

Salvatrucha (MS-13) criminal gang in Central

America, a no nonsense approach now is most

certainly warranted.

Colombia has failed to end 50 years of conflict

with the guerrillas. Oddly enough Cubans,

known for their decades of revolutionary

violence and intervention in other nations, have

been hosting truce talks between FARC and

Colombian government representatives since

November 2012.

MS-13, a violent transnational organized

criminal gang that operates in Central America,

Mexico, Canada, and the U.S., had its beginnings

in Los Angeles in the 1980s.

During that time Honduras, Nicaragua and El

Salvador were in turmoil and conflict with leftist

guerrillas pushing communism into their

borders. Many Salvadoran families left all

behind to flee from the terror and atrocities.

Many of the youth settled in the greater Los

Angeles area, learned English and turned to

crime and gang wars with African Americans

and Mexicans for control of criminal turf; and

many were incarcerated.

From 2000 to 2004, thousands of convicted

gang members were deported to the Northern

Triangle area of Central America. Many of them

did not speak Spanish, having left El Salvador

when they were quite young. Soon they bonded

within their former criminal elements.

The homicide rate began to escalate rapidly

during this deportation process of MS-13 and

rival gang Barrio 18 members. Some gang

members next moved to Mexico and assimilated

with Mexican gangs, as others reentered the U.S.

again illegally and took up residence in

major U.S. cities where they remain today.

Truces with both the FARC guerrillas and MS13, and the government of El Salvador, have

consistently resulted in betrayal and distrust

with remnants of a charade in cessation of

violence and other hostilities.

In what could be described as a skillfully

exploited situation by the FARC, the Colombian

government continues to negotiate with the

rebels to end a conflict that is believed to have

killed more than 200,000 persons, and

internally displaced some 3 million people. The

battle has been called Latin Americas longestrunning war.

There is no doubt that the FARC has taken

advantage of previous concessions by the

Colombian government, to talk, disarm and seek

peace.

Today FARC leaders are continuing to insist on

no jail time for their atrocities, plus they want

the right to run for political office if they are to

demobilize and peacefully reintegrate. Yet they

continuously and consistently refuse to disarm.

What is not clear is whether or not the truces

represent an overall durable policy option for

the Colombian and Salvadoran governments?

Many of the concerns involve the thoughts that

truces involving violent groups and gangs, and

agreement legitimized gangs, reinforce the

authority of their leaders, deepen cohesion

among their rank and file, and actually increase

crime.

While such agreements sometimes tend to bring

a temporary drop in violence, they have proven

difficult to transform into long-term

arrangements. A noticeable example was in

2010, when civil society groups helped mediate a

truce between rival gangs in Medellin, Colombia,

but the deal fell through after several months,

followed by an escalation in violence.

Central America has sustained some of the

highest homicide rates in the world. Honduras

has been described as the most violent nation in

Central America. Much of the violence is

attributed to fighting between MS-13 and Barrio

18 transnational gangs with their

members throughout Central America, Mexico,

and North America. Within the U.S., these gangs

are deeply involved in organized criminal

activities and they often act as hired muscle for

local and international drug trafficking

organizations. Additionally, the groups

independently engage in a range of criminal

endeavors, including extortion and human

trafficking.

In the 1990s the FARC, via the leftist Patriotic

Union Party, continued to wage war during

peace talks with the Colombian government. The

Colombian government consistently cited the

lack of commitment by the FARC as to the

process of talks, while the latter continued its

criminal acts.

It eventually became clear that the FARC had

much higher political support. At his annual

State of the Nation address in the National

Assembly, on January 11, 2008, then President

of Venezuela Hugo Chavez referred to the FARC

as "a real army that occupies territory in

Colombia. Too, Chavez stated that the FARC

were not terrorists because they had a political

goal.

Further troubling issues with El Salvador arose

in a report in 2013, that indicated Jose Luis

Merino, a leader of El Salvador's Farabundo

Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), a

leftwing political party, arranged a drug lords

meeting with the Colombian FARC on a flight

coordinated with Venezuelan President Nicolas

Maduro. This alleged new evidence revealed

that Venezuelan President Maduro, when

serving as Venezuelas Foreign Minister,

worked to improve the FMLNs access to drug

trafficking."

In April of last year the government of El

Salvador announced that the truces between the

country's main Mara street gangs had not

worked, and that killings and attacks against

police have risen again. (Violence is escalating

again in El Salvador).

Colombia's FARC guerrillas recently announced

a one month unilateral ceasefire for July 20.

Perhaps another spin of the wheel?

\

Jerry Brewer is C.E.O. of Criminal Justice

International Associates, a global threat

mitigation firm headquartered in northern

Virginia. His website is located at

www.cjiausa.org. TWITTER: CJIAUSA

Jerry Brewer Published Archives

You might also like

- Transnational Criminal Insurgency - A Complicated Web of ChaosDocument5 pagesTransnational Criminal Insurgency - A Complicated Web of ChaosJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Rio's Olympic Games and Concerns Due To Hemispheric PerilsDocument4 pagesRio's Olympic Games and Concerns Due To Hemispheric PerilsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Jerry Brewer ProductionsDocument17 pagesJerry Brewer ProductionsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Sine Qua Non, Mexico Must Restructure Its Security IntentionsDocument7 pagesSine Qua Non, Mexico Must Restructure Its Security IntentionsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Argentina's Ambitious New Security Plan Shows Real PromiseDocument5 pagesArgentina's Ambitious New Security Plan Shows Real PromiseJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Political Expediency and Exploitation of FARC Peace TalksDocument8 pagesThe Political Expediency and Exploitation of FARC Peace TalksJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Argentina and The USA Seeking To Revive Cooperation Versus CrimeDocument8 pagesArgentina and The USA Seeking To Revive Cooperation Versus CrimeJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Mexico's Incongruous National Security Aims and StrategiesDocument4 pagesMexico's Incongruous National Security Aims and StrategiesJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- With Respect To Cuba Is Obama Guileful Duped or A Dim BulbDocument8 pagesWith Respect To Cuba Is Obama Guileful Duped or A Dim BulbJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- U.S. and Mexico Border Security Rhetoric Lacks Proper FocusDocument4 pagesU.S. and Mexico Border Security Rhetoric Lacks Proper FocusJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Mexico's Version of Border Woes Trumps U.S. UnderstandingDocument6 pagesMexico's Version of Border Woes Trumps U.S. UnderstandingJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- With Respect To Cuba Is Obama Guileful Duped or A Dim BulbDocument15 pagesWith Respect To Cuba Is Obama Guileful Duped or A Dim BulbJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Cuba and FARC, and Their Sinister Presence in VenezuelaDocument5 pagesCuba and FARC, and Their Sinister Presence in VenezuelaJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Paraguayan Criminals and Guerrillas Are Multinational ThreatsDocument4 pagesParaguayan Criminals and Guerrillas Are Multinational ThreatsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Death of A Chilean Spy Chief, Operation Condor and The CIADocument5 pagesThe Death of A Chilean Spy Chief, Operation Condor and The CIAJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Latin America's Counterintelligence Capabilities Are FrailDocument6 pagesLatin America's Counterintelligence Capabilities Are FrailJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Evo Morales Denounces Mexico, Calling It A 'Failed Model'Document4 pagesEvo Morales Denounces Mexico, Calling It A 'Failed Model'Jerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Thaw and Engagement With Cuba's 56 Year Old Communist DictatorshipDocument6 pagesThaw and Engagement With Cuba's 56 Year Old Communist DictatorshipJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Paradoxes of Law Enforcement in The Western HemisphereDocument6 pagesThe Paradoxes of Law Enforcement in The Western HemisphereJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Synthesis and Vision of Valuing Human Life Beyond The U.S. BorderDocument3 pagesThe Synthesis and Vision of Valuing Human Life Beyond The U.S. BorderJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Ferguson Report Reflects and Exacerbates DOJ RetaliationDocument5 pagesFerguson Report Reflects and Exacerbates DOJ RetaliationJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Self-Inflicted Misery and Tyranny Among Latin America's LeftDocument4 pagesSelf-Inflicted Misery and Tyranny Among Latin America's LeftJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The U.S. and Mexico Must Focus On Cooperative Security BenefitsDocument5 pagesThe U.S. and Mexico Must Focus On Cooperative Security BenefitsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Continuing Crime and Insecurity in Northern Central AmericaDocument5 pagesContinuing Crime and Insecurity in Northern Central AmericaJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Argentine President Is Again Mired in Corruption AllegationsDocument5 pagesArgentine President Is Again Mired in Corruption AllegationsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Rule of Law - Shopping For Justice Under The Guise of Civil RightsDocument4 pagesThe Rule of Law - Shopping For Justice Under The Guise of Civil RightsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- Facts and Subterfuge Regarding The U.S. and Cuba ProposalsDocument4 pagesFacts and Subterfuge Regarding The U.S. and Cuba ProposalsJerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Western Hemisphere Faces Serious Crime Challenges in 2015Document6 pagesThe Western Hemisphere Faces Serious Crime Challenges in 2015Jerry E. Brewer, Sr.No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- United States v. Devin Melcher, 10th Cir. (2008)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Devin Melcher, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Factsheet Nifty High Beta50 PDFDocument2 pagesFactsheet Nifty High Beta50 PDFRajeshNo ratings yet

- Breach of Contract of Sales and Other Special LawsDocument50 pagesBreach of Contract of Sales and Other Special LawsKelvin CulajaraNo ratings yet

- Patrice Jean - Communism Unmasked PDFDocument280 pagesPatrice Jean - Communism Unmasked PDFPablo100% (1)

- Solution Manual For Modern Advanced Accounting in Canada 9th Edition Darrell Herauf Murray HiltonDocument35 pagesSolution Manual For Modern Advanced Accounting in Canada 9th Edition Darrell Herauf Murray Hiltoncravingcoarctdbw6wNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 Home and Branch Office AccountingDocument2 pagesActivity 1 Home and Branch Office AccountingMitos Cielo NavajaNo ratings yet

- History MCQs 2 - GKmojoDocument9 pagesHistory MCQs 2 - GKmojoAnil kadamNo ratings yet

- Bihar High Court Relaxation Tet Case JudgementDocument4 pagesBihar High Court Relaxation Tet Case JudgementVIJAY KUMAR HEERNo ratings yet

- Cape Law Syllabus: (Type The Company Name) 1Document3 pagesCape Law Syllabus: (Type The Company Name) 1TrynaBeGreat100% (1)

- Doosan Generator WarrantyDocument2 pagesDoosan Generator WarrantyFrank HigueraNo ratings yet

- EuroSports Global Limited - Offer Document Dated 7 January 2014Document314 pagesEuroSports Global Limited - Offer Document Dated 7 January 2014Invest StockNo ratings yet

- Dumonde v. Federal Prison Camp, Maxwell AFB Et Al (INMATE 2) - Document No. 3Document4 pagesDumonde v. Federal Prison Camp, Maxwell AFB Et Al (INMATE 2) - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Construction Agreement 2Document2 pagesConstruction Agreement 2Aeron Dave LopezNo ratings yet

- Emortgage Overview Eclosing - BBoikeDocument7 pagesEmortgage Overview Eclosing - BBoikechutiapanti2002No ratings yet

- BPT Bulletproof Standards SmallDocument1 pageBPT Bulletproof Standards Smallalex oropezaNo ratings yet

- Chem Office Enterprise 2006Document402 pagesChem Office Enterprise 2006HalimatulJulkapliNo ratings yet

- LGU Governance and Social Responsibility Course OutlineDocument2 pagesLGU Governance and Social Responsibility Course OutlineDatulna Benito Mamaluba Jr.0% (1)

- MOCK EXAMS FINALSDocument3 pagesMOCK EXAMS FINALSDANICA FLORESNo ratings yet

- Organizational ManagementDocument7 pagesOrganizational ManagementMacqueenNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law (Relationship Between Council of Minister and President)Document16 pagesConstitutional Law (Relationship Between Council of Minister and President)Sharjeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- BISU COMELEC Requests Permission for Upcoming SSG ElectionDocument2 pagesBISU COMELEC Requests Permission for Upcoming SSG ElectionDanes GuhitingNo ratings yet

- Canadian Administrative Law MapDocument15 pagesCanadian Administrative Law MapLeegalease100% (1)

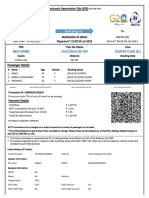

- 14312/BHUJ BE EXP Sleeper Class (SL)Document2 pages14312/BHUJ BE EXP Sleeper Class (SL)AnnuNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Organizational Communication: Muhammad Alfikri, S.Sos, M.SiDocument6 pagesEthics in Organizational Communication: Muhammad Alfikri, S.Sos, M.SixrivaldyxNo ratings yet

- Phrasal Verbs CardsDocument2 pagesPhrasal Verbs CardsElenaNo ratings yet

- MIHU Saga (Redacted)Document83 pagesMIHU Saga (Redacted)Trevor PetersonNo ratings yet

- 3 - Supplemental Counter-AffidavitDocument3 pages3 - Supplemental Counter-AffidavitGUILLERMO R. DE LEON100% (1)

- Assessing Police Community Relations in Pasadena CaliforniaDocument125 pagesAssessing Police Community Relations in Pasadena CaliforniaArturo ArangoNo ratings yet

- Uan Luna & Ernando AmorsoloDocument73 pagesUan Luna & Ernando AmorsoloGeorge Grafe100% (2)

- Modules For Online Learning Management System: Computer Communication Development InstituteDocument26 pagesModules For Online Learning Management System: Computer Communication Development InstituteAngeline AsejoNo ratings yet