Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Helical Broaching

Uploaded by

guytr2Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Helical Broaching

Uploaded by

guytr2Copyright:

Available Formats

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

DESCRIPTION OF HELICAL BROACH GEOMETRY USING

MATHEMATICAL MODELS ASSOCIATED WITH CAD 3D MODELS

Daniel Amoretti Gonalves, daniagon@terra.com.br

Henrique von Paraski, henrique@vonparaski.com

Rolf Bertrand Schroeter, rolf@emc.ufsc.br

Laboratrio de Mecnica de Preciso (LMP), UFSC, Caixa Postal-476 EMC, 88.010-970 Florianpolis/SC, Brazil

Abstract: In order to supply the constant demand for quality and low price, companies continually need to upgrade

their technologies, knowledge on their products and production processes. In reaching these goals, the rationalization

of the production process is one of the main factors affecting the cost and quality of products. In this context, the

broaching process offers a solution for certain types of operations. The helical broaching process uses a single tool

that performs roughing, semi-finishing and finishing in a machining cycle, making the process highly productive and

attractive in terms of mass production. Helical broach is a tool of high value (and high cost), but if it is well designed,

properly manufactured and used within the specifications, it provides a great return on investment. This tool presents

high geometrical complexity, which directly affects the efficiency of the process. In order to gain a better

understanding of the geometry of the broach and to correctly design the tool, a study is proposed herein based on a

mathematical model which describes the tool geometry and compares it to CAD 3D models. These mathematical model

algorithms are then implemented in computational language. With the inputting of some parameters, like rake angle

and helical spline angle, it is possible to obtain some important information on the tool geometry, for example, the

cross sectional area, the moment of inertia and the tool pitch. To obtain these characteristics through other methods,

like direct measurement or using a CAD 3D software, for example, more time consuming and expensive methods would

be necessary, and in some cases it would even be impossible. Thus, these models are used to gain information on many

geometrical characteristics of the broach used in the design in a quicker and cheaper way.

Keywords: broaching, modeling, simulation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Broaching is a process of machining where the cutting movement is predominantly linear, characterized by the use

of a tool with multiple teeth with increasing pitches, arranged in series (Stemmer, 2005). The tool used is called broach,

and it can be forced by traction or compression inside or outside the piece. The operation consists of removing material

from a workpiece in order to build straight and flat surfaces or a specific internal or external cross section. Almost any

cross section can be broached as long as all machined surfaces remain parallel to the direction of the broach movement.

The exception to this rule is uniform rotation sections such as spiral gear teeth, produced by twisting the broach tool

during the machining cycle (SME, 1983).

In the broaching process, the cutting speed is the only machining parameter there can be changed during execution

of the process. In helical broaching, the cutting speed is a combination of a linear motion and a rotating motion. Other

parameters such as feed and depth of cutting are defined by the geometry of the tool.

Historically, broaches have been designed based on trial and error or on the designer`s experience (Sutherland et al.,

1996). The greater the precision of the component required, the less the design should be based on experience. To

design a broach in the early life cycle of a product, a model of how the broach will perform during the operation would

be extremely advantageous (Sutherland et al., 1996). The broach, a tool of high cost, lacks key information required for

its design and manufacture, such as the behavior of the cutting forces during the machining cycle, stress distribution in

the tool, machining angles, and so on.

2. THEORY REVIEW

2.1. Helical broach

The helical broach differs from the traditional traction broach since it or the workpiece is rotated, depending on

whether or not the teeth of the broach produce a helix with an angle corresponding to the required piece. For some

applications, when the helix angle is smaller than 15, the rotating broach does not need to be held by an actuator,

because the workpiece has the ability to auto-rotate due to the small helix angle (Stemmer, 2005; SME, 1983).

However, in cases of large-scale production or large helix angles, there must be a tool system of rotation synchronized

with the linear movement. An example of a helical broach is shown in Fig. 1.

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

Figure 1. Typical internal helical broach with standard nomenclature used

2.2. Geometry of helical broach teeth

One of the key features of the geometry of the broach teeth is the space between them, i.e., the distance between one

teeth and the next in the same row, since this determines the number of teeth working on the piece simultaneously. This

is an important design factor because the tool tension values can be calculated. With a helical broach the pitch can be

mathematically determined according to the number of tooth gullets, the number of broach grooves, and the helix angle,

as seen in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Tooth gullets, grooves and helix angles

The rake angle plays an important role in the development of broaching tools due to its influence on the

mechanisms of chip formation and its consequences in terms of the strength of machining, cutting temperature, chip

adherence to the tooth, etc. For materials such as medium to low carbon steel, the use of rake angles of 15-20, and for

aluminum the use of rake angles of 10-15, is recommended (Stemmer, 2005; Walsh and Cormier, 2006; ASM, 1997).

The rise per tooth asf is also one of the main features, because it permits the calculation of the cutting force, together

with the tooth width and the material constant specific cutting pressure. With the value of the cutting force it is then

possible to ascertain the tension on the tool and, therefore, the tool resistance can also be calculated. For steel with

medium to low carbon the use of cutting depths of 0.03 to 0.05mm is recommended. For aluminum a cutting depth of

0.1 to 0.2 mm is recommended (Stemmer, 2005; Walsh and Cormier, 2006; ASM, 1997).

Besides these main features considered in the design of a broach, there are also other parameters, for example : chip

bags radius r1 and r2, which are needed to receive the chips during machining; the clearance angle , which affects the

tool life, because the smaller the angle the greater the friction on the flank and also the less the tool needs to be sharpen.

In Fig. 3 the main elements of broach tooth geometry can be seen.

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

Figure 3. Main tooth angles

3. GEOMETRIC MODEL DESIGNED IN CAD 3D

The model, designed in CAD 3D software, used in this study refers to a broach used by a company in its production

line, and it was designed to produce helical gears. The original design, drawn in CAD 2D, was converted into a CAD

3D model of the tool, providing key features for the modeling.

3.1. Broach modeling with CAD 3D

The model designed in CAD 3D provides important information on the tool geometry, showing the model space.

This method, however, when compared to purely mathematical models, has the disadvantages of being laborious and

time consuming. In Fig. 4 some steps for modeling in CAD 3D can be observed.

Figure 4. Helical broach modeling processes

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

3.2. Broach mathematical modeling

Compared to models designed in CAD 3D, a drawback of mathematical models is the need to develop equations

which represent the tool. This can be very time consuming and often it is even impossible to obtain an analytical

solution. In these cases, it is only possible to obtain a result through numerical methods or by simplifying the real

situation.

In this study, the first step was to determine the edge position of each broach tooth in space using parametric

equations, which represent the paths followed by a row of teeth and the tooth gullets. At the intersection of these two

equations the cutting edges are found. To find these points a parameter represented by Eq. (1) is used:

t=

p2

2 k

p1 + p2

nc

(1)

where t is the parameter used to calculate the position of the tooth, p2 is the helix pitch of the tooth gullets, p1 is the helix

pitch of the groove (Fig. 5), is the initial angle of the groove, which is dependent on the number of grooves in the

broach, nc is the number of tooth gullets and k, where k Z, is a variable. This variable is used to determine the

positions of all teeth in a row. The values of interest for this variable vary for each row of teeth and will be discussed

later.

Figure 5. Section of a helical broach showing the pitch of the tooth gullets and the grooves helix.

The initial angle of the groove, , is determined through its angular symmetry distributions in the broach, taking one

as a reference. It can be calculated through Eq. (2):

n

2. ; n , 0 n < nr

nr

(2)

To determine the radius of the cross section in terms of a parameter, Eq. (3) is used:

r (t ) =

Do

p

+ 1 .( D f Do ).t

2 4. .L

where Do is the initial diameter, Df is the final diameter, L is the length of roughing teeth (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Design of a broach showing the initial and final diameters as well as the length

(3)

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

To obtain the position of each edge, Eqs. (4), (5) and (6) are used:

x = r (t ) cos(t + )

(4)

y = r (t ). sin(t + )

(5)

z=

p1

.t

2.

(6)

where x, y and z represent the Cartesian coordinates of a point in space and is the initial angle of the teeth row. The

points of interest for the model are those which are located within the range:

0 z L

Therefore:

nc.

nc

p + p2

. 2. .L. 1

k

+

2.

2.

p1. p2

(7)

In other words, the k values which are of interest for the model are all of the values which lie within these limits.

For the value of the cross sectional area of this tool the actual area represented in Fig. 7 can be approximated. This

figure shows a division into 3 parts. Each part is identical to the other two and is formed by the sum of two areas: area 1

and area 2 (A1 e A2, respectively). Area 1 has a constant radius from 0 to 1, and area 2 has a variable radius and ranges

from 0 to 2.

Figure 7. Mathematical model of the cross sectional area

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

For area 2, the radius is determined by Eq. (8):

r2 = h + h.

2

2

(8)

where h is the gullet depth and D is the diameter of the section.

The equations representing the model of the cross sectional area shown above are:

D

h

2

0

A1 =

A2 =

r2

rdrd1 =

rdrd 2 =

1D

h .1

2 2

1 2 2

dr

2 0 r 2

(9)

(10)

since:

d =

2

h

.dr

(11)

Substituting (11) in (10) we find that:

3

2 D D

3

A2 =

h

6.h 2 2

(12)

Finally, the total area is:

A = 3.( A1 + A2 )

(13)

Another important factor in terms of the future tool design is the polar moment of inertia, used in the calculation of

stresses. Based on Fig. 7 the following equations can be drawn:

4

h

D

h

2

3

02 r drd = 4 .1

J1 =

(14)

For area 2:

2

J2 =

r2

r 3drd =

1 2 4

r2 dr

4 0

(15)

since:

d =

2

h

.dr

(16)

Substituting (16) for (15) we find that:

5

2 D D

5

J2 =

h

20.h 2 2

(17)

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

Finally:

J = 3.( J 1 + J 2 )

(18)

To obtain a better adjustment of these values for the area and polar moment of inertia to the values found in the

CAD 3D model, the angles 1 and 2 change according the position on the broach and have following relations:

1 =

4.nc.L

2 = 1

.z

z 2.

.

8.L nc

(19)

(20)

where z is the position on the broach, L is the length of roughing teeth and nc is the number of tooth gullets.

Taking into account the trapezoidal shape of the broach teeth, the size of the tooth edge can be inferred based on the

design data related to the crest length and the tooth base. In this case, the variation of the tooth width will be linear with

the diameter and the coefficients of the equation can be determined using the following conditions:

1 When d=D0, b=b0;

2 When d=Df, b=bf;

where D0 and Df are the initial and the final diameters and b0 and bf are the initial and final length of the edge.

Thus, the following linear system is found:

b0 = A.D0 + B

b f = A.D f + B

(21)

Solving the linear system, the equation for b is the following:

b=

d D0

.(b f b0 ) + b0

D f D0

(22)

4. COMPARISON BETWEEN CAD 3D AND MATHEMATICAL MODELS

In order to validate the mathematical model, the results can be compared to those of the model designed in CAD 3D.

For the size of the edge, the values obtained for the first teeth in CAD 3D were around 3.65mm and using the

mathematical model they were 3.70mm, which represents a percentage difference of around 1.3%. The CAD 3D last

teeth has the value of 2.42mm and using the mathematical model the value was 2.70mm, which represents a percentage

difference of around 11.5%. The comparison between these two models can be seen in Fig. 8.

Figure 8. Comparison between the tooth widths obtained from the mathematical and CAD models.

For the cross sectional area in the CAD 3D model, the value at the beginning of the broach was 151.3mm2 and in the

mathematical model it was 140.3mm2, a difference of 6.6%. At the end of the broach the model in CAD 3D had a value

Proceedings of COBEM 2009

Copyright 2009 by ABCM

20th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering

November 15-20, 2009, Gramado, RS, Brazil

of 206.9mm2 and in the mathematical model it was 198.2mm2, a difference of 4.2%. A comparison between these two

models can be seen in Fig 9.

Figure 9. Comparison between the cross sectional areas obtained with the mathematical and CAD models.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Both methods used in this study showed advantages and disadvantages related to their usage. The advantages of the

graphical method using CAD 3D in terms of visualization of the final product and reliability of the result were evident.

However, when there is a need to predict the cutting forces or obtain the size and position of each edge related to the

piece to be machined, the drawbacks of this method become clear, since the cutting force of each edge would need to be

calculated manually. In contrast, the mathematical method is the best alternative to study the cutting force since, once

the model equations are obtained, it is easy to implement these equations in an algorithm.

The differences between the values found using the two methods are mainly due to the broach geometry

simplifications in the mathematical model. However, for application in predicting the machining forces, this variation is

negligible, since the variation in the cutting force due to the formation of chips generates a greater variation.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support provided by POSMEC and CAPES.

6. REFERENCES

ASM, 1997, Metals Handbook , Vol. 16, Machining, American Society for Metals.

SME, 1983, Tool and Manufacturing Engineers Handbook, Vol 1: Machining. Fourth Edition.

Stemmer, C. E., 2005, Ferramentas de corte II, 3rd ed, Ed. UFSC, Florianpolis, Brazil, 314 p.

Sutherland, J.W., Salisbury, E.J. and Hoge, F.W., 1996, A Model for the Cutting Force System in the Gear Broaching

Process, Int. J. Mach. Tolls Manufact. Vol. 37, No. 10, pp. 1409-1421.

Walsh, R.A. and Cormier, D., 2006, McGraw-Hill Machining and Metalworking Handbook, Ed. McGraw-Hill, 3rd

ed., 974 p.

7. RESPONSIBILITY NOTICE

The authors are solely responsible for the printed material included in this paper.

You might also like

- Study Regarding The Optimal Milling Parameters For Finishing 3D Printed Parts From Abs and Pla MaterialsDocument7 pagesStudy Regarding The Optimal Milling Parameters For Finishing 3D Printed Parts From Abs and Pla MaterialsDaniel BarakNo ratings yet

- Gear Skiving ProcessDocument8 pagesGear Skiving ProcessrethinamkNo ratings yet

- Design and Fabrication of Metal Spinning ComponentsDocument6 pagesDesign and Fabrication of Metal Spinning ComponentsAnonymous VRspXsmNo ratings yet

- Face Gears: Geometry and Strength: Ulrich Kissling and Stefan BeermannDocument8 pagesFace Gears: Geometry and Strength: Ulrich Kissling and Stefan BeermannosaniamecNo ratings yet

- Wear Analysis of Multi Point Milling Cutter using FEADocument8 pagesWear Analysis of Multi Point Milling Cutter using FEAAravindkumarNo ratings yet

- Tool TolerancesDocument7 pagesTool TolerancesrugwNo ratings yet

- 10 PDFDocument11 pages10 PDFRyanNo ratings yet

- Decomposition of forging die for high speed machiningDocument9 pagesDecomposition of forging die for high speed machiningMohammed KhatibNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Twist Drills, Geometric Modeling, Solidmodeling TechniquesDocument4 pagesKeywords: Twist Drills, Geometric Modeling, Solidmodeling TechniqueserkmorenoNo ratings yet

- Sand Casting Using RP and Conventional MethodsDocument5 pagesSand Casting Using RP and Conventional MethodsjlplazaolaNo ratings yet

- E8/8#) .8/8F-5&G$ (-G56: Gh&i@'7jklm'ij@Document6 pagesE8/8#) .8/8F-5&G$ (-G56: Gh&i@'7jklm'ij@Adarsh KumarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Surface GrindingDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Surface Grindingqyptsxvkg100% (1)

- A New Dynamic Model For Drilling and Reaming Processes Yang2002Document13 pagesA New Dynamic Model For Drilling and Reaming Processes Yang2002RihabChommakhNo ratings yet

- Dsi and Anly ProjectDocument17 pagesDsi and Anly ProjectGurpreet singhNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Tool Tolerances on Gear QualityDocument6 pagesThe Influence of Tool Tolerances on Gear QualityHARJIT KOHLINo ratings yet

- Gear DesignDocument10 pagesGear DesignDragoș Gabriel Hrihor100% (2)

- Trueness of Milled Prostheses According To Number of Ball-End Mill BursDocument6 pagesTrueness of Milled Prostheses According To Number of Ball-End Mill Bursabdulaziz alzaidNo ratings yet

- Thrust Force Prediction of Twist Drill Tools Using A 3DDocument16 pagesThrust Force Prediction of Twist Drill Tools Using A 3DNguyen Danh TuyenNo ratings yet

- 4592-Article Text-8789-1-10-20201230Document13 pages4592-Article Text-8789-1-10-20201230Ayman EttahallouNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Computational Engineering Research (IJCER)Document8 pagesInternational Journal of Computational Engineering Research (IJCER)International Journal of computational Engineering research (IJCER)No ratings yet

- 5 Axis Milling PerformanceDocument8 pages5 Axis Milling PerformanceHamza RehmanNo ratings yet

- Analytical Models For High Performance Milling. Part II: Process Dynamics and StabilityDocument11 pagesAnalytical Models For High Performance Milling. Part II: Process Dynamics and StabilityAditya Pujasakti YuswiNo ratings yet

- Finite Element Method: Project ReportDocument15 pagesFinite Element Method: Project ReportAtikant BaliNo ratings yet

- Drill ModelingDocument13 pagesDrill Modelingantonio87No ratings yet

- Sheet Incremental Forming: Advantages of Robotised Cells vs. CNC MachinesDocument23 pagesSheet Incremental Forming: Advantages of Robotised Cells vs. CNC MachinesManolo GipielaNo ratings yet

- Modeling and Simulation of Turning OperationDocument8 pagesModeling and Simulation of Turning OperationtabrezNo ratings yet

- Klocke Kroemer ICG15Document11 pagesKlocke Kroemer ICG15ranim najibNo ratings yet

- Forming, Cross Wedge Rolling and Stepped ShaftDocument4 pagesForming, Cross Wedge Rolling and Stepped ShaftMrLanternNo ratings yet

- A Review Paper On Latest Trend On Face Milling Tool-41282Document3 pagesA Review Paper On Latest Trend On Face Milling Tool-41282ajayNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis Using AutocadDocument9 pagesDesign and Analysis Using AutocadsudhakarNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0043164823001709 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S0043164823001709 MainRaphaël ROYERNo ratings yet

- Gear ShavingDocument6 pagesGear ShavingRuchira Chanda InduNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Ultra Precision Progressive Die Making For Sheet Metal Forming by Computer SimulationDocument4 pagesA Study On The Ultra Precision Progressive Die Making For Sheet Metal Forming by Computer SimulationGerardo ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Paper 1Document7 pagesPaper 1Akeel WannasNo ratings yet

- PROJECT REVIEW 2 FinalDocument23 pagesPROJECT REVIEW 2 FinalNani DatrikaNo ratings yet

- Hole Quality in DrillingDocument11 pagesHole Quality in DrillingJack BurtonNo ratings yet

- FEA of Orbital Forming Used in Spindle AssemblyDocument6 pagesFEA of Orbital Forming Used in Spindle AssemblyEldori1988No ratings yet

- Modeling GD&T of crankshaft flangeDocument6 pagesModeling GD&T of crankshaft flangeKarthik KarunanidhiNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Broaching Tool Design: Intelligent Computation in Manufacturing Engineering - 4Document6 pagesOptimization of Broaching Tool Design: Intelligent Computation in Manufacturing Engineering - 4Rishikesh GunjalNo ratings yet

- Acropolis Technical Campus University Question Paper Solution June-2013 (Me-603, Metal Cutting & CNC M/C)Document10 pagesAcropolis Technical Campus University Question Paper Solution June-2013 (Me-603, Metal Cutting & CNC M/C)vijchoudhary16No ratings yet

- CAD-based Simulation of The Hobbing ProcessDocument11 pagesCAD-based Simulation of The Hobbing ProcessGabriel MariusNo ratings yet

- Sheet Metal Puching Metal FormingDocument27 pagesSheet Metal Puching Metal FormingTarundeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Basic Gear Terminology and CalculationDocument10 pagesBasic Gear Terminology and CalculationTesseract spyderNo ratings yet

- An experimental investigation on surface quality and dimensional accuracy of FDM componentsDocument7 pagesAn experimental investigation on surface quality and dimensional accuracy of FDM componentsnewkid2202No ratings yet

- 57 07-05-21 Isaif8 0021-ChenDocument10 pages57 07-05-21 Isaif8 0021-ChenEslam NagyNo ratings yet

- Camworks Dragster CHTP 1Document15 pagesCamworks Dragster CHTP 1Mayrym Rey ConNo ratings yet

- CIRP Annals - Manufacturing Technology: S. Chatti, M. Hermes, A.E. Tekkaya (1), M. KleinerDocument4 pagesCIRP Annals - Manufacturing Technology: S. Chatti, M. Hermes, A.E. Tekkaya (1), M. Kleiner1ere année ingNo ratings yet

- Proc Ese 1233Document4 pagesProc Ese 1233Carlos ArenasNo ratings yet

- Rapid Prototipyng Foundries ArticleDocument5 pagesRapid Prototipyng Foundries ArticlebeiboxNo ratings yet

- Paper ShobraDocument15 pagesPaper ShobrapatigovNo ratings yet

- FEA and Wear Rate Analysis of Nano Coated HSS Tools For Industrial ApplicationDocument6 pagesFEA and Wear Rate Analysis of Nano Coated HSS Tools For Industrial ApplicationpawanrajNo ratings yet

- Ijmet 06 12 002Document9 pagesIjmet 06 12 002subramanianNo ratings yet

- 1990 - Computer-Aided Preform Design in Forging of An Airfoil Section BladeDocument10 pages1990 - Computer-Aided Preform Design in Forging of An Airfoil Section BladeNguyen Hoang DungNo ratings yet

- Submerged Arc Welding ParametersDocument14 pagesSubmerged Arc Welding ParametersbozzecNo ratings yet

- Investigations For Deducing Wall Thickness of Aluminium Shell Casting Using Three Dimensional PrintingDocument5 pagesInvestigations For Deducing Wall Thickness of Aluminium Shell Casting Using Three Dimensional PrintingR Moses KrupavaramNo ratings yet

- Yigit 2019Document8 pagesYigit 2019YB2020No ratings yet

- Manual of Engineering Drawing: British and International StandardsFrom EverandManual of Engineering Drawing: British and International StandardsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Carp 1Document95 pagesCarp 1anvaralizadehNo ratings yet

- DIY Belt SanderDocument2 pagesDIY Belt Sanderguytr2No ratings yet

- Corbin Technical Bulletin Volume 4Document149 pagesCorbin Technical Bulletin Volume 4aikidomoysesNo ratings yet

- Turkish Mauser InfoDocument2 pagesTurkish Mauser Infoguytr2100% (4)

- Dasifier The Up-Downdraft Gasifier For Metal Melting 2001 PDFDocument3 pagesDasifier The Up-Downdraft Gasifier For Metal Melting 2001 PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- Ed's RedDocument4 pagesEd's RedtwinscrewcanoeNo ratings yet

- Bluing Steel 4Document1 pageBluing Steel 4guytr2No ratings yet

- 10 Dollar Telescope PlansDocument9 pages10 Dollar Telescope Planssandhi88No ratings yet

- Size of Tackle: The First Thing To Know Is What: OR LeatherDocument5 pagesSize of Tackle: The First Thing To Know Is What: OR Leatherelectricnusi100% (7)

- AR Trigger Cassette Body RevisionsDocument1 pageAR Trigger Cassette Body Revisionsguytr2No ratings yet

- Art of Manliness - Man Cook BookDocument148 pagesArt of Manliness - Man Cook Bookabhii100% (8)

- 870 Emergency Food Preparation Militia Cookbook PDFDocument37 pages870 Emergency Food Preparation Militia Cookbook PDFodhiseoNo ratings yet

- Cylinder SizesDocument3 pagesCylinder Sizesdeathblade55No ratings yet

- CVBG Tip Of The Month: Robb Gunter's Super Quench FormulaDocument1 pageCVBG Tip Of The Month: Robb Gunter's Super Quench Formulaguytr2No ratings yet

- 1991 Memo Warned of Mercury in Shots. Page 1 of 2Document5 pages1991 Memo Warned of Mercury in Shots. Page 1 of 2guytr2No ratings yet

- Mill Control Tips PDFDocument19 pagesMill Control Tips PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- Foundry PracticeDocument11 pagesFoundry PracticeNatalie WyattNo ratings yet

- 12 Months Harvest A Guide To Preserving Food by Ortho BooksDocument100 pages12 Months Harvest A Guide To Preserving Food by Ortho Booksguytr2No ratings yet

- Bridgeport-Style Milling Machine Advantages PDFDocument4 pagesBridgeport-Style Milling Machine Advantages PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- Lathe G&M Code Card PDFDocument2 pagesLathe G&M Code Card PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- Haas LatheDocument160 pagesHaas Lathem_najman100% (1)

- Tons To Punch Round Holes in Mild Steel Cold PDFDocument1 pageTons To Punch Round Holes in Mild Steel Cold PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- Lathe Control Book PDFDocument42 pagesLathe Control Book PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- Lathe Control Tips PDFDocument14 pagesLathe Control Tips PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- HAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1997 Issue 2 - Summer PDFDocument17 pagesHAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1997 Issue 2 - Summer PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- HAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1997 Issue 3 - Fall PDFDocument19 pagesHAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1997 Issue 3 - Fall PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- HAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1998 Issue 5 - Spring PDFDocument19 pagesHAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1998 Issue 5 - Spring PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- HAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1998 Issue 4 - Winter PDFDocument19 pagesHAAS CNC MAGAZINE 1998 Issue 4 - Winter PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- HAAS CNC MACHINING MAGAZINE 1997 Issue 1 - Spring PDFDocument13 pagesHAAS CNC MACHINING MAGAZINE 1997 Issue 1 - Spring PDFguytr2No ratings yet

- An Antarasiddhi, The First Independent Treatise: Masahiro InamiDocument19 pagesAn Antarasiddhi, The First Independent Treatise: Masahiro InamiFengfeifei2018No ratings yet

- DD Cen TR 10347-2006Document14 pagesDD Cen TR 10347-2006prabagaran88% (8)

- Final StereogramDocument16 pagesFinal StereogramsimNo ratings yet

- PLOTINUS: On Beauty (Essay On The Beautiful)Document12 pagesPLOTINUS: On Beauty (Essay On The Beautiful)Frederic LecutNo ratings yet

- RenderingDocument6 pagesRenderingJuno PajelNo ratings yet

- SmogDocument5 pagesSmogAlain MoratallaNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring GuideDocument12 pagesTherapeutic Drug Monitoring GuidePromise NcubeNo ratings yet

- WK-3508F IPTV Gateway DatasheetDocument7 pagesWK-3508F IPTV Gateway DatasheetComunidad Tecnolibre.netNo ratings yet

- Winbond Elec W25q128jvfiq c111478Document75 pagesWinbond Elec W25q128jvfiq c111478Guilherme El KadriNo ratings yet

- Answer Example Source Questio N Type Topic: Glish/Doanddoeshasandhave/Bjgd /post - HTMDocument92 pagesAnswer Example Source Questio N Type Topic: Glish/Doanddoeshasandhave/Bjgd /post - HTMFarhan HakimiNo ratings yet

- TDS - RheoFIT 762Document2 pagesTDS - RheoFIT 762Alexi ALfred H. TagoNo ratings yet

- Baobawon Island Seafood Capital Bless Amare Sunrise Resort Sam Niza Beach Resort Oklahoma Island Rafis Resort Inday-Inday Beach ResortDocument42 pagesBaobawon Island Seafood Capital Bless Amare Sunrise Resort Sam Niza Beach Resort Oklahoma Island Rafis Resort Inday-Inday Beach ResortAmber WilsonNo ratings yet

- Sap MRP ConfigDocument23 pagesSap MRP Configsharadapurv100% (1)

- Mtech Geotechnical Engineering 2016Document48 pagesMtech Geotechnical Engineering 2016Venkatesh ThumatiNo ratings yet

- Enzymatic Browning and Its Prevention-American Chemical Society (1995)Document340 pagesEnzymatic Browning and Its Prevention-American Chemical Society (1995)danielguerinNo ratings yet

- Improving MV Underground Cable Performance - Experience of TNB MalaysiaDocument4 pagesImproving MV Underground Cable Performance - Experience of TNB Malaysialbk50No ratings yet

- BS en 10108-2004Document14 pagesBS en 10108-2004Martijn GrootNo ratings yet

- Ahmed 2022Document20 pagesAhmed 2022Mariela Estefanía Marín LópezNo ratings yet

- PHYSICS - Quiz Bee ReviewerDocument2 pagesPHYSICS - Quiz Bee ReviewerMikhaela Nazario100% (3)

- Energy Monitoring With Ultrasonic Flow MetersDocument35 pagesEnergy Monitoring With Ultrasonic Flow MetersViswa NathanNo ratings yet

- Pic24fj256ga705 Family Data Sheet Ds30010118eDocument424 pagesPic24fj256ga705 Family Data Sheet Ds30010118eD GzHzNo ratings yet

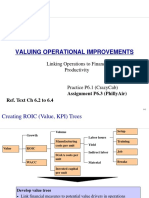

- 2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityDocument14 pages2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityAidan HonnoldNo ratings yet

- Op-Amp Comparator: Astable (Or Free-Running) Multivibrators Monostable MultivibratorsDocument5 pagesOp-Amp Comparator: Astable (Or Free-Running) Multivibrators Monostable MultivibratorsYuvaraj ShanNo ratings yet

- Dr. Kumar's Probability and Statistics LectureDocument104 pagesDr. Kumar's Probability and Statistics LectureAnish KumarNo ratings yet

- 02 - AFT - Know Your Pump & System Curves - Part 2ADocument8 pages02 - AFT - Know Your Pump & System Curves - Part 2AAlfonso José García LagunaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Engineering ManagementDocument4 pagesChapter 1 Engineering ManagementGeorge Russell80% (5)

- NSBI 2022-2023 FormsDocument16 pagesNSBI 2022-2023 FormsLove MaribaoNo ratings yet

- FM200 Clean Agent System Installation GuideDocument6 pagesFM200 Clean Agent System Installation Guidehazro lizwan halimNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing: Assignment ON Nursing ClinicDocument5 pagesCollege of Nursing: Assignment ON Nursing ClinicPriyaNo ratings yet