Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Matters Which May Be Arbitrated Under Indian Law

Uploaded by

Vikash GoelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Matters Which May Be Arbitrated Under Indian Law

Uploaded by

Vikash GoelCopyright:

Available Formats

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

HIDAYATULLAH NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY

ALTERNATE DISPUTE RESOLUTION PROJECT

ON

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

SUBMITTED TO

MR. MANOJ KUMAR

VIKASH GOEL

SEMESTER VI

ROLL NO. 172

SUBMITTED ON

18TH FEBRUARY, 2015

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I feel highly elated to work on this dynamic topic on MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE. Its

ratio is significant in todays era when there is a grat importance given to arbitration as dispute resolution

method and people fail to know which disputes are arbitrable.

The practical realization of this project has obligated the guidance of many persons. I express my deepest

regard for our faculty MR. Manoj Kumar. His consistent supervision, constant inspiration and invaluable

guidance and suggestions have been of immense help in carrying out the project work with success.

I extend my heartfelt thanks to my family and friends for their moral support and encouragement.

Vikash Goel

Semester VI TH

Roll no. 172

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

Acknowledgement2

Introduction.........4

Objective6

Research methodology6

Law applicable to question of arbitrability7

Substantive rules on objective arbitrability8

Duty t deal with lack of arbitrability ex-officio9

The Non- Arbitrability doctrine.10

Case law relating to Arbitrability.13

Conclusion ...15

Bibliography.....15

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

INTRODUCTION

Arbitrability is one of the issues where the contractual and jurisdictional natures of international

commercial arbitration meet head on. According to Carbonneau and Janson,

arbitrability

determines the point at which the exercise of contractual freedom ends and the public mission of

adjudication begins. It involves the simple question of what types of issues can and cannot be

submitted to arbitration. Party autonomy espouses the right of parties to submit any dispute to

arbitration. It is the parties right to opt out of the normal national court jurisdiction. National

laws often impose restrictions or limitations on what matters can be referred to and resolved by

arbitration. For example, states or state entities may not be allowed to enter into arbitration

agreements at all or may require a special authorization to do so. This is called SUBJECTIVE

ARBITRABILITY. More important than the restrictions relating to the parties are limitations

based on the subject matter in issue. This is OBJECTIVE ARBITRABILITY. Certain disputes

may involve such sensitive public policy issues that it is felt that they should only be dealt with

by the judicial authority of state courts. An obvious example is criminal law which is generally

the domain of the national courts. These disputes are not capable of settlement by arbitration.

This restriction on party autonomy is justified to the extent that arbitrability is a manifestation of

national or international, public policy. Consequently, arbitration agreements covering those

matters will, in general, not be considered valid, will not establish the jurisdiction of the

arbitrators and subsequent award may not be enforced. In the U.S. the term arbitrability is

often used in a wider sense covering the whole issue of the tribunals jurisdiction.

To understand the prevailing international situation with regard to arbitrability, three important

aspects are to be studied. They are-

i)Law applicable to questions of arbitrability,

ii) The limitations imposed in different countries, or Substantive Rules on Objective arbitrability;

and

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

iii) Whether arbitration tribunals have the right and duty to deal with the issue of arbitrability on

their own initiative.(Lack of arbitrability)

ARBITRABILITY DEFINED

Wiktionary defined arbitrability as the characteristics of being arbitrable. It is the ability of a

matter to be arbitrated. The term arbitrability is used to determine whether the dispute under

the arbitration agreement could be settled by arbitration. The international understanding of

arbitrability stems from the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of

Foreign Arbitral Awards, which in Article II(1) provides that each contracting state shall

recognize an arbitration agreement concerning a subject matter capable of settlement by

arbitration, and Article V(2)(a) provides that an arbitral award may be refused recognition and

enforcement if the subject matter of the difference is not capable of settlement by arbitration

under the law of that country.

Outside the United States, the term arbitrability has a reasonably precise and limited meaning:

i.e., whether specific classes of disputes are barred from arbitration because of national

legislation or judicial authority. Courts often refer to public policy as the basis of the bar.

Thus, the subject matter of the claim is the key to arbitrability in international arbitration, and

the question to be asked is, under the law of the place of arbitration or the state where award

enforcement is being sought, are the specific claims capable of settlement by arbitration or must

they be resolved in a national court?

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

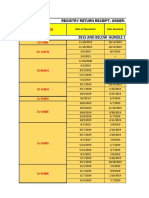

Objectives of the research

1.

2.

3.

4.

To know the basic concepts refund under income Tax Act, 1961,

To study the persons entitled to claim refund

To study the procedure for claiming refund,

To study the concept of interest on refund.

Research methodology

This work being a Doctrinal work is descriptive in nature. Secondary and Electronic resources have been

largely used to gather information and data on the topic.

Books and other reference materials as suggested by Faculty of Taxation have been primarily helpful in

giving this project a firm structure. Websites, dictionaries and articles have also been referred to.

LAW APPLICABLE TO QUESTIONS OF ARBITRABILITY

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

Determination of the law governing arbitrability is of considerable importance. Despite the

generally prevailing tendency to increase the scope of arbitrable disputes national laws

frequently differ from each other. A number of disputes which are not arbitrable under the law of

one country are arbitrable in another country where the interests involved are considered to be

less important. The approach to bribery is an example of existing differences. In many countries,

whilst bribery is a vitiating factor in all contracts, it can be considered by arbitrators. In other

countries not only is bribery illegal but also to preclude it from being legitimized, by a

commercial or consultancy arrangement, if allegations of bribery are raised they cannot be

considered by arbitrators. Consequently, in some countries, consultancy contracts relating to

public procurement are not arbitrable because of the prevalence of excessive commissions

considered to be bribes. The law governing arbitrability of a dispute may depend on where and at

what stage of proceedings the question arises. Tribunals may apply different criteria than courts

in determining this law and the criteria applied by courts at the post-award stage may differ from

those at the pre-award stage.

International Conventions vs. National Laws:

Under the various conventions the obligations of national courts to enforce arbitration

agreements and awards only exist where the dispute is arbitrable. Therefore these conventions

generally regulate which law governs arbitrability. If a dispute is arbitrable according to this law,

courts may not rely on non-arbitrability of the dispute under a different law to refuse

enforcement of the arbitration agreement or award.

The New York Convention provides for the law of arbitrability only from the perspective of

enforcement. It requires the enforcing court to look to its own law to determine whether the

dispute is arbitrable. Art-V (2) (a) provides Recognition and enforcement of an arbitral award

may also be refused if the competent authority in the country where recognition and enforcement

is sought finds that: The subject matter of the difference is not capable of settlement by

arbitration under the law of that country

SUBSTANTIVE RULES ON OBJECTIVE ARBITRABILITY

7

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

Every national law determines which types of disputes are the exclusive domains of national

courts and which can be referred to arbitration. This differs from state to state reflecting the

political, social and economic prerogatives of the state, as well as its general attitude towards

arbitration. It involves a balancing of the mainly domestic importance of reserving certain

matters for exclusive decision of courts with the more general public interest of promoting trade

and commerce through an effective means of dispute settlement.

Therefore, the decision may be different in cases arising in a purely national context from that in

relation to international transaction. In Mitsubishi Vs. Soler,1 the U.S. Supreme Court held that

in an international context the ambit of arbitration may be wider than in a national context.

Though the case only dealt with US Law, the decision describes what the prevailing view is now.

The case also evidences a second general trend: the increase in the types of disputes which can

be referred to international arbitration. While originally arbitration was often limited to claims

arising directly out of a contract, gradually more and more claims based on statutes, for example

regulating important parts of national economy in the public interest, have become arbitrable. In

Mitsubishi vs. Soler, the Court declared anti-trust disputes to be arbitrable which inAmerican

Safety Equipment Corp Vs. J.P. Maguire & Co.2 were still held not to be arbitrable in a

domestic context. Although in general limits on arbitrability of disputes arise from public policy

only few laws make express reference to the notion of public policy.335 Not only is the notion

often too vague to give clear guidance but in the contemporary arbitration friendly environment

not every rule of public policy justifies reserving the disputes involved for determination by state

courts.3 Therefore, despite the underlying public policy consideration, different criteria are

adopted in determining arbitrability. Some national laws refer to very broad notions such as

disputes involving economic interest (Germany ZPO Sec.1030 (1), or dispute involving

property (Switzerland PIL Art-177). Other national laws rely on the narrower concept of

capability of the parties to reach an agreement. The Model Law does not contain any definition

1 473 US 614

2 6, 3335 et seq

3 Kirry, Arbitrability:Current Trends in Europe, 12 Arb. Int. 373 (1996) 374-379.

8

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

of which disputes are arbitrable. Quite to the contrary Art-1(5) Model Law provides that it is not

intended to affect other laws of the state which preclude certain disputes being submitted to

arbitration.

DUTY TO DEAL WITH THE LACK OF ARBITRABILITY EX OFFICIO

In the majority of cases the non-arbitrality of a dispute is raised by one party seeking to preclude

arbitration. It may prefer to have the dispute decided by the courts. There are, however, cases

where none of the parties invokes the lack of arbitrability.They may either not have realized it or

may have an interest in having their dispute settled in private. For example, parties to contracts

involving bribery or certain illegal conduct may accept the need for their dispute to be resolved

but may not want the relevant authorities to be informed about their contract which will

invariably be the case if the dispute is dealt with in the courts. In such cases the question arises

whether the arbitration tribunal has the right itself to raise the issue of arbitrability even though

the parties do not challenge the jurisdiction of the tribunal. This was done by Judge Lager green

in ICC case 1110.375 After studying the pleadings filed by the parties and oral and written

witness statement, the sole arbitrator raised the question of his jurisdiction ex officio, to entertain

the subject matter of the case and stated

In this respect both parties affirmed the binding effect of their contractual undertakings and my

competence to consider and decide their case in accordance with theterms of reference. However,

in the presence of a contract in dispute of the nature set out hereafter, condemned by public

policy decency and morality, I cannot in the interest of due administration of justice avoid

examining the question of jurisdiction on my own motion. It is worth noting under the New

York Convention recognition and enforcement of an award may be refused ex officio if the

competent authority in the country where recognition and enforcement is sought finds that (a) the

subject matter of the difference is not capable of settlement by arbitration under the law of that

country, or (b) the recognition or enforcement of the award would be contrary to the public

policy of that country.

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

One could argue that arbitration tribunals are not part of any national judicial system and

therefore do not owe any allegiance to a particular state. As long as the parties want to have their

dispute decided by arbitration the tribunal should do so irrespective of the fact that its award may

later be set aside for lack of arbitrability. The duty towards the parties to render an enforceable

award only exists as long as the parties have not renounced it. However, the preferred view is

that an arbitration tribunal should on its own initiative deny jurisdiction if the dispute is not

arbitrable on the basis of the facts submitted by the parties. This is not contrary to the principle of

NE ULTRA PETITA i.e. not raising an issuing outside the arbitrators authority (ArtV(1)(c) of

New York Convention) but is the result of an application of the law to the facts. It is provided

under Section 8 of Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

THE NON-ARBITRABILITY DOCTRINE

The New York Convention contains various exceptions to the general obligation, set forth in ArtII to enforce written arbitration agreements. In particular, Art.II (1) does not require arbitration of

disputes that are not capable of settlement by arbitration. Similarly, Art-V (2) (a) provides that

an arbitration award need not be recognized if the subject matter of the difference is not capable

of settlement by arbitration under the law of the country where recognition is sought. Together,

these provisions permit the assertion of non-arbitrability defences to the enforcement of

arbitration agreements and awards under the Convention. Other international arbitration

conventions and treaties contain similar exceptions. Art-II (3) requires the enforcement of

arbitration agreements, provided that they are not null and void without any reference to a nonarbitrability or public policy defence. It has been suggested that, as a consequence, arbitration

agreements must be enforced, even if they pertain to non-arbitrable claims and if the resulting

award would be therefore unenforceable under Art-V(2)(a) or (b).378 Neither courts nor most

commentators have accepted this view, generally reasoning that non-arbitrability defences

permitted by Art-II(1) and Art-V(2) are incorporated by Art-II(3)s NULL AND VOID

exception.

As noted above, Art-II (1) of the New York Convention does not require recognition of

arbitration agreements unless they concern a subject-matter capable of settlement by

arbitration. Like other exceptions under Art-II and V, the nonarbitrability doctrine raises a

10

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

threshold choice of law question: what law(s) apply to determine whether a claim or dispute is

non-arbitrable for purposes of Art-II (3)? Among commentators, there is no agreement on what

governing law should apply.

Several choices are possible:

First, the Convention might be regarded as establishing (albeit almost entirely by implication) a

uniform international definition of non-arbitrability, from which no nation could deviate.

Second, the law governing the parties arbitration agreement might define nonarbitrability, as

Art-II (1) and V(1)(a) imply.

Third, non-arbitrability might be defined by the law of the place where the arbitration is

conducted and the award made, as also implied by Art-V (1)(a).

Fourth, the law of the nation in which enforcement of an award will eventually be sought might

define non-arbitrability, as Art-V (2)(a) and (b) specifically contemplate.

Fifth, the law of the judicial forum where an arbitration agreement is sought to be enforced could

govern non-arbitrability; and

Finally, non-arbitrability might be defined by the law that provides the basis for the relevant

substantive claim.

Indian Scenario

In India, Certain disputes like criminal offences of public nature, disputes arising out of illegal

agreements4, and disputes relating to status, such as divorce, cannot be referred to arbitration.

The broad categories of disputes which are considered to be non-arbitrable are:

- antitrust and competition

- insolvency

- intellectual property rights

4 T.M.L. Financial Services Ltd. V. Vinod Kumar

11

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

- illegality and fraud

- bribery and corruption

The well recognized example of non-arbitrable disputes are:

Disputes relating to rights and liabilities which give rise to or arise out of criminal

offences;

Matrimonial disputes relating to divorce, judicial separation, restitution of conjugal

rights, child custody;

Guardianship matters;

Insolvency and winding up matters;

Testamentary matters;

Eviction or tenancy matters governed by special statutes where the tenant enjoys statutory

protection against eviction and only the specified courts are conferred jurisdiction to

grant eviction or decide on the disputes. 5

ARBITRABLE ISSUES

Where a judicial proceeding is commenced in a matter which is subject matter of an arbitration

agreement, the judicial forum is bound to refer the matter for arbitration by the arbitral tribunal.

This provision implies that if the matter is an arbitrable matter, and is covered by the arbitration

agreement, the matter must be decided by arbitration rather than by adjudication. The underlying

crucial issue for this provision is what exactly is an arbitrable matter, or what are the limits to

arbitrability?

Courts in several jurisdictions have rendered rulings on arbitrability. Matters that can be settled

by arbitration include:

5 Union of India v Rent Tribunal, Jodhpur

12

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

Basically all disputes of Civil or Quasi Civil nature involving Civil Rights fall within the

jurisdiction of Arbitration.

Almost all disputes commercial, civil, labour and family disputes in respect of which the

parties are entitled to conclude a settlement can be settled by Arbitration.

Disputes involving joint ventures, construction projects, partnership differences, intellectual

property rights, personal injury, product liabilities, professional liability, real estate securities,

contract interpretation and performance, insurance claim and Banking & non-Banking

transaction disputes fall within the jurisdiction of Arbitration.

It is expanding to the areas or construction health care, telecommunication, entertainment and

technology based industries.

CASE LAWS RELATING TO ARBITRABILITY

The distinction between disputes which are capable of being decided by arbitration and those

which are not is brought out in the following decisions of the court:

In Haryana Telecom Limited V. Sterlite Industries India Limited 6the Supreme Court

held that Section 8(1) of Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 provides that the judicial

authority before whom an action is brought in a matter, will refer the parties to arbitration

the same matter in accordance with the arbitration agreement. This, however, postulates,

in the opinion of the court, that what can be referred to the arbitrator is only that dispute

or matter which the arbitrator is competent or empowered to decide; The claim in a

petition for winding up is not for money. The petition for winding up is to be filed under

the Companies Act. The company has become commercially insolvent and therefore,

should be wound up. The power to order winding up of a company is contained under

the Companies Act and is conferred on the court. An arbitrator, notwithstanding any

agreement between the parties, would have no jurisdiction to order winding up of a

company. The matter which is pending before the High Court in which the application

6 (1999) (5) SCC 688

13

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

was filed by the petition herein was relating to winding up of the company. That could

obviously not be referred to arbitration.

In Olympus Superstructures (P) Limited V. Meena Vijay Khetan 7the Supreme Court

considered whether an arbitrator has the power and jurisdiction to grant specific

performance of contracts relating to immoveable property. In this regard the Supreme

Court held that there is no prohibition in the Specific Relief Act, 1963 that issues relating

to specific performance of contract relating to immoveable property cannot be referred to

arbitration. Nor is there such a prohibition contained in the Arbitration and Conciliation

Act, 1996 as contrasted with Section 15 of the English Arbitration Act, 1950 or Section

48(5)(b) of the English Arbitration Act, 1996 which contained a prohibition relating to

specific performance of contracts concerning immoveable property.

In Keventer Agro Limited V. Seegram Co. Limited Apo 498 of 1997 the Supreme Court

held that disputes arising out of illegal agreements and disputes relating to status, such as

divorce, which cannot be referred to arbitration. However if in respect of the facts

relating to a criminal matter, say, physical injury, if there is a right of damages for

personal injury, then such a dispute can be referred to arbitration. Similarly a husband

and wife may, refer to arbitration the terms on which they shall separate, because they

can make a valid agreement between themselves on that matter.

In Chiranjilal Shrilal Goenka V. Jasjit Singh 8the Supreme Court held that grant of

probate is a judgment in rem and is conclusive and binding not only the parties but also

the entire world; and therefore, courts alone will have exclusive jurisdiction to grant

probate and an arbitral tribunal will not have jurisdiction even if consented concluded to

by the parties to adjudicate up on the proof or validity of the will.

7 (1999) 5 SCC 651

8 (1993) 2 SCC 507

14

MATTERS WHICH MAY BE ARBITRABLE

CONCLUSION

Thus we can conclude that arbitrability is an evolving topic with each country adopting different

stand on different matters but a constant behavior can be seen due to compliance with New York

Convention on arbitration. The Indian Law itself does not specify the exhaustive list on matters

arbitrable but leave the issue to the arbitrator to decide under Section 8 of Arbitration and

Conciliation Act, 1996. Generally matters of public police or criminal nature are non- arbitrable

whereas all other matters are considered arbitrable for enabling speedy disposal of cases in the

country. There is need to further the scope of arbitrable subject- matter to include commercial

transaction including securities matter where both parties agree to it to enable speedy disposal.

An amendment to the act to specify clearly matters which may be arbitrable can be a step in the

right direction and clear all the doubts in the mind of parties. Generally it is observed that the

parties are unaware of the fact whether their disputes are arbitrableor not and go ahead with

arbitration after which the decision is annulled later on which lead to a wasteof time and money.

Therefore there is need for a proper source from where it can be determined whether matters are

arbitrable or not.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

MARKANDA, PC -ARBITRATION AND CONCILIATION, LEXISNEXIS, NAGPUR

MALHOTRA, OP - ARBITRATION AND CONCILIATION, THOMSON REUTERS.

Redfern and Hunter, Law and Practice of International Commercial Arbitration (4th

Edition Sweet

15

You might also like

- Setting Aside Arbitral Awards Under Section 34Document15 pagesSetting Aside Arbitral Awards Under Section 34akhilgraj0% (1)

- ADR Methods for Family and Industrial DisputesDocument16 pagesADR Methods for Family and Industrial DisputesKUNAL1221No ratings yet

- Top 5 Things You Must Know About Canadian Vaping LawsDocument4 pagesTop 5 Things You Must Know About Canadian Vaping LawsSoukhya VisputeNo ratings yet

- Arbitration and Dispute ResolutionDocument5 pagesArbitration and Dispute ResolutionUtkarsh SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- GENERICIDEDocument5 pagesGENERICIDEkanupriyaNo ratings yet

- Family Law ProjectDocument15 pagesFamily Law ProjectSakshi Singh BarfalNo ratings yet

- Central University of South Bihar: School of Law and GovernanceDocument22 pagesCentral University of South Bihar: School of Law and GovernancepushpanjaliNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis Judicial Review and Abuse of PowerDocument21 pagesCritical Analysis Judicial Review and Abuse of PowerSri Nur HariNo ratings yet

- 3RD Sem Project Family LawDocument19 pages3RD Sem Project Family Lawsapna pandeyNo ratings yet

- Chanakya National Law UniversityDocument5 pagesChanakya National Law UniversityDeepak ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Res Gestae Exception to Hearsay RuleDocument16 pagesRes Gestae Exception to Hearsay Rulelokesh4nigamNo ratings yet

- A Project On Indian Trademark Law: Compliance With The TripsDocument20 pagesA Project On Indian Trademark Law: Compliance With The TripsharshalNo ratings yet

- Understanding the UNCITRAL Model LawDocument4 pagesUnderstanding the UNCITRAL Model LawArnav DasNo ratings yet

- Critical Anlaysis of Clause 49 0F Listing AgreementDocument37 pagesCritical Anlaysis of Clause 49 0F Listing AgreementRohit DongreNo ratings yet

- CLICK & SHRINK WRAP CONTRACTS - KamakshiDocument2 pagesCLICK & SHRINK WRAP CONTRACTS - KamakshikamakshiNo ratings yet

- Evidence Rough Draft MatDocument3 pagesEvidence Rough Draft MatMaitreya SahaNo ratings yet

- Framing of Suit PDFDocument22 pagesFraming of Suit PDFShashwat PathakNo ratings yet

- Contracts Promissory Estoppel Research PaperDocument8 pagesContracts Promissory Estoppel Research PaperPARMESHWARNo ratings yet

- VoluntaryDocument189 pagesVoluntaryRaGa JoThi50% (2)

- Family Law CaseDocument5 pagesFamily Law CaseAayushNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Compatibility of Article 21 with Reference to Concept of LibertyDocument54 pagesConstitutional Compatibility of Article 21 with Reference to Concept of LibertyrichaNo ratings yet

- Rights and Obligations of The PatenteeDocument11 pagesRights and Obligations of The PatenteeHumanyu KabeerNo ratings yet

- Common Intention Under Section 34 IPCDocument11 pagesCommon Intention Under Section 34 IPCAvinash KumarNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study On The Difference Between Fraud and Undue InfluenceDocument21 pagesA Comparative Study On The Difference Between Fraud and Undue InfluenceAishani ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Akhil Gangesh 14, ADR Sem VIDocument15 pagesAkhil Gangesh 14, ADR Sem VIakhilgangeshNo ratings yet

- Environment Law Porject Sem 4 Sara ParveenDocument20 pagesEnvironment Law Porject Sem 4 Sara ParveenSara ParveenNo ratings yet

- Open Challenges ListDocument2 pagesOpen Challenges ListShivam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Ejusdem GenerisDocument7 pagesEjusdem GenerisAakanksha BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu National Law School: Plea Bargaining: Violation of Fundamental RightsDocument14 pagesTamil Nadu National Law School: Plea Bargaining: Violation of Fundamental RightsRavi shankarNo ratings yet

- Concept of Shareholders: A Criticle StudyDocument17 pagesConcept of Shareholders: A Criticle Studysudarshan kumarNo ratings yet

- Generic Mark and Its TreatmentDocument16 pagesGeneric Mark and Its TreatmentLogan DavisNo ratings yet

- Ipc ProjectDocument13 pagesIpc ProjectAradhya JainNo ratings yet

- Health & Medicine Law Final DraftDocument12 pagesHealth & Medicine Law Final DraftDeepak RavNo ratings yet

- Company Law - II "Intellectual Property Issues in Pharmaceutical Industries in Merger and Acquisition - A Critical Analysis"Document23 pagesCompany Law - II "Intellectual Property Issues in Pharmaceutical Industries in Merger and Acquisition - A Critical Analysis"devvrat garhwalNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Final DraftDocument10 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Final DraftHarshSinghNo ratings yet

- Probation Project - Probation in Sexual OffencesDocument10 pagesProbation Project - Probation in Sexual OffencesGaurav kumar RanjanNo ratings yet

- Central University of South BiharDocument17 pagesCentral University of South BiharRajeev RajNo ratings yet

- Impact of NDPS Act on Drug Abuse in IndiaDocument56 pagesImpact of NDPS Act on Drug Abuse in IndiaPravar JainNo ratings yet

- Institutional ArbitrationDocument16 pagesInstitutional ArbitrationSohanNo ratings yet

- Alteration in Object Clause-50Document5 pagesAlteration in Object Clause-50Divesh GoyalNo ratings yet

- TPA Project 6th TrimesterDocument18 pagesTPA Project 6th TrimesterNickyta UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Alternative Dispute Resolution ProjectDocument11 pagesAlternative Dispute Resolution ProjectSiddhant BarmateNo ratings yet

- I. Historical Background: - This Code Specifically Provided For Arbitration in Book CompromisosDocument11 pagesI. Historical Background: - This Code Specifically Provided For Arbitration in Book CompromisostaleneNo ratings yet

- PARTNERSHIP ACT IMPORTANCEDocument14 pagesPARTNERSHIP ACT IMPORTANCEshashwat kumarNo ratings yet

- Concept and Meaning of InterpretationDocument14 pagesConcept and Meaning of InterpretationAzharNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalisation on Indian Stock MarketDocument27 pagesImpact of Globalisation on Indian Stock MarketNadeem Lone0% (3)

- Bhopal Gas Tragedy ProjectDocument21 pagesBhopal Gas Tragedy ProjectAnjali Bhatt100% (12)

- Abatement of Criminal Appeals Under Section 394 of CrPCDocument21 pagesAbatement of Criminal Appeals Under Section 394 of CrPCSomya YadavNo ratings yet

- Law of Crimes - T.Document10 pagesLaw of Crimes - T.Tejaswa MohantaNo ratings yet

- CRPC-1 Project 2017ballb118Document24 pagesCRPC-1 Project 2017ballb118kazan kazanNo ratings yet

- Property Law ProjectDocument15 pagesProperty Law ProjectrishabhNo ratings yet

- Company Law - 2 Project FinalDocument15 pagesCompany Law - 2 Project FinalNishida TirpudeNo ratings yet

- Freedom of Speech on Social MediaDocument20 pagesFreedom of Speech on Social MediaRAKESH KUMAR BAROINo ratings yet

- B.A. LL.B. (I L) I P L (VI S) : Roject ORKDocument15 pagesB.A. LL.B. (I L) I P L (VI S) : Roject ORKAbhimanyu SinghNo ratings yet

- AditiBanerjee (2225) IEA FDDocument23 pagesAditiBanerjee (2225) IEA FDAditi BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- D - S M N R U L: Analysis On Countervailing Measures Under WTODocument11 pagesD - S M N R U L: Analysis On Countervailing Measures Under WTOashwaniNo ratings yet

- Prohibited Subsidies: Chanakya National Law UniversityDocument22 pagesProhibited Subsidies: Chanakya National Law UniversityRajat KashyapNo ratings yet

- Niversity OF Etroleum Nergy Tudies Ollege OF Egal Studies: "Appeal"Document20 pagesNiversity OF Etroleum Nergy Tudies Ollege OF Egal Studies: "Appeal"Nitish Kumar NaveenNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ProjectDocument19 pagesLabour Law ProjectdivyavishalNo ratings yet

- Extraordinary Published by Authority No. 1235, Cuttack Saturday, June 29, 2013/ ASADHA 8, 1935 Law DepartmentDocument9 pagesExtraordinary Published by Authority No. 1235, Cuttack Saturday, June 29, 2013/ ASADHA 8, 1935 Law DepartmentVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- The Orissa Gazette: DocumentsDocument8 pagesThe Orissa Gazette: DocumentsVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Keshavananda BharatiDocument912 pagesKeshavananda BharatiHarshakumar KugweNo ratings yet

- Effect of DisplacementDocument14 pagesEffect of DisplacementVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Vikash Goel Sem 7. Evidence ActDocument19 pagesVikash Goel Sem 7. Evidence ActVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Exame Note For Constitution of IndiaDocument46 pagesExame Note For Constitution of IndiaKumar RameshNo ratings yet

- Vikash Goel, Sem-9, CPC ProjectDocument21 pagesVikash Goel, Sem-9, CPC ProjectVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of GSTDocument2 pagesSalient Features of GSTVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Soga PDFDocument50 pagesSoga PDFPooja MeenaNo ratings yet

- Transnatrional ProjectDocument31 pagesTransnatrional ProjectVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- MediaDocument25 pagesMediaVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Hons Paper I SyllabusDocument2 pagesCriminal Law Hons Paper I SyllabusVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Trial Before Court of Session ExplainedDocument16 pagesTrial Before Court of Session ExplainedVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Trial Before Court of Session ExplainedDocument16 pagesTrial Before Court of Session ExplainedVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Consti-2 PrivacyDocument34 pagesConsti-2 PrivacyVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Budget CommentDocument4 pagesBudget CommentVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Land Laws FINALDocument19 pagesLand Laws FINALVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument17 pagesEconomicsVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Tpa FinalDocument18 pagesTpa FinalVikash GoelNo ratings yet

- Bascos vs CA Decision UpheldDocument3 pagesBascos vs CA Decision Upheldlovekimsohyun89No ratings yet

- United States v. Threatt, 4th Cir. (2009)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Threatt, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Book 2 Titles 1-8Document142 pagesCriminal Law Book 2 Titles 1-8Jillian BatacNo ratings yet

- Rules On Electronic FilingDocument5 pagesRules On Electronic FilingMaan ElagoNo ratings yet

- Thomas Gioeli's Motion To Set Aside The VerdictDocument51 pagesThomas Gioeli's Motion To Set Aside The VerdictDaniel A. McGuinnessNo ratings yet

- Balancing Prisoner Rights and Corrections FunctionsDocument2 pagesBalancing Prisoner Rights and Corrections FunctionsMichael MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Registry Return Receipt List OldDocument208 pagesRegistry Return Receipt List OldGabriel Atienza CasipleNo ratings yet

- Samantha Kofer's Career Takes Her to Rural VirginiaDocument8 pagesSamantha Kofer's Career Takes Her to Rural VirginiaEunice Saavedra0% (1)

- ClosingstatementDocument1 pageClosingstatementapi-298342736No ratings yet

- Use of Legislation - Good GovernanceDocument12 pagesUse of Legislation - Good Governance1year BallbNo ratings yet

- Article 10 RVPDocument6 pagesArticle 10 RVPQuennie QuiapoNo ratings yet

- Motion for Judgment on the PleadingsDocument3 pagesMotion for Judgment on the PleadingsJohn Paul Fabella50% (2)

- The Whistleblower Protection (Amendment) Bill, 2015Document4 pagesThe Whistleblower Protection (Amendment) Bill, 2015Rajat MishraNo ratings yet

- Common Law v. StatutoryDocument13 pagesCommon Law v. StatutoryDannyDolla100% (2)

- Understanding Prison Management in The Philippines: A Case For Shared GovernanceDocument50 pagesUnderstanding Prison Management in The Philippines: A Case For Shared GovernanceGrace Talamera-SandicoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDocument28 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Grammar For PetDocument3 pagesGrammar For Petjanaka chamindaNo ratings yet

- Wilma Hazel Kennedy V State 1955Document5 pagesWilma Hazel Kennedy V State 1955legalmattersNo ratings yet

- NativismDocument14 pagesNativismJudy LepomaNo ratings yet

- Skinhead ReportDocument32 pagesSkinhead ReportCharisse Van Horn100% (1)

- Encinas v. Agustin, JR PDFDocument17 pagesEncinas v. Agustin, JR PDFMarion Yves MosonesNo ratings yet

- Nestle Phil Vs Uniwide Sales IncDocument9 pagesNestle Phil Vs Uniwide Sales IncShaira Mae CuevillasNo ratings yet

- Justice: A Tragedy in Four Acts, by John Galsworthy (1910) - William Falder, A Young Clerk in ADocument6 pagesJustice: A Tragedy in Four Acts, by John Galsworthy (1910) - William Falder, A Young Clerk in AShivam KumarNo ratings yet

- Henry Fingerprint ClassificationDocument7 pagesHenry Fingerprint ClassificationkeshavNo ratings yet

- Torts Mid Terms ReviewerDocument10 pagesTorts Mid Terms ReviewerNingClaudioNo ratings yet

- Eric Murdock United Airlines Federal Lawsuit DocumentsDocument24 pagesEric Murdock United Airlines Federal Lawsuit DocumentsBenjamin ZhangNo ratings yet

- S V Kenneth Orina :trial Within TrialDocument33 pagesS V Kenneth Orina :trial Within TrialAndré Le RouxNo ratings yet

- Organized Crime in India: Problems and PerspectivesDocument48 pagesOrganized Crime in India: Problems and PerspectivesRitika MehraNo ratings yet

- Witness Affidavit in Jeepney Accident CaseDocument4 pagesWitness Affidavit in Jeepney Accident CaseJazz Adaza100% (2)

- Canton Police Explorers Information 2017Document4 pagesCanton Police Explorers Information 2017pacerNo ratings yet