Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HRM Human Capital

Uploaded by

Rosa WillisCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HRM Human Capital

Uploaded by

Rosa WillisCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction

Research in brief

Improving human

resources management:

some practical questions

and answers

Nowadays in the area of company organisation,

including companies dedicated to international

hospitality, travel and tourism, nobody denies

the importance of human resources (HR) to

business success, and expressions such as ``HR

represent an investment rather than a cost''

have become quite usual. New proposals for

human resources management (HRM) have

appeared, of which, because of their topicality

and impact in publications, we highlight three:

the best practices approach, management by

competencies, and the management of

intellectual capital. The tourism industry has

not been excluded from those, and it is known,

through published papers, that certain

companies recognise the importance of people

to their businesses and include HR practices

contained in the above proposals (e.g. Florida

Theme Park (Mayer, 2002); Forte Hotel Group

(Erstad, 2001); Fivestar hotel (Haynes and

Fryer, 2000)).

Santiago Melian Gonzalez

The author

Santiago Melian Gonzalez is Professor of Human Resource

Management at the University of Las Palmas de Gran

Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Islas Canarias, Spain.

Keywords

Human resource management, Performance management,

Company performance, Hotel and catering industry, Spain

Abstract

Practically nobody denies the importance of human

resources (HR) to company management. There are many

works which show that companies' managing their HR in a

specific way, obtain positive business results. However,

some of those studies select, a priori, organisations with a

certain type of HR practice in order to assess their impact on

performance. This work, with no prior knowledge of their

human resources management (HRM), analyses the HRM in

a number of accommodation establishments, using three

up-to-date approaches to that managerial function as a

reference. The results indicate that many of the

establishments do not follow the proposals of those

approaches. Therefore, based on those results, the focus is

on those three perspectives to make recommendations that

enable the establishments to improve their HRM.

Objectives

In some of the studies of HRM, organisations

with high performance HRM are selected a

priori. But what happens in companies with no

information published about their HRM, and

when nothing is known about it? Do they use

HRM in the same way as the companies in

previous studies? Using those questions as a

starting-point, this work attempts to analyse the

HRM in a number of accommodation

establishments about whose HRM nothing was

previously known. The objective is to check the

extent to which the precepts of the three abovementioned theoretical frameworks are reflected

in the HRM practices of the establishments. A

brief description of all three follows.

Electronic access

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister

Best practices perspective

The works of authors such as Pfeffer (1994,

1998) and Huselid (1995) propose a series of

HR practices beneficial to business results, in

which little or no attention is paid to other

contingency factors. This way of understanding

the HRM has been named the ``best practices''

or ``high performance practices'' approach. This

perspective receives more empirical support

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is

available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0959-6119.htm

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume 16 . Number 1 . 2004 . pp. 59-64

# Emerald Group Publishing Limited . ISSN 0959-6119

DOI 10.1108/09596110410516570

59

Improving human resources management

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume 16 . Number 1 . 2004 . 59-64

Santiago Melian Gonzalez

than a contingency approach, although it is not

without its critics, and comprises the following

HR practices:

.

employment security;

.

selective hiring;

.

extensive training;

.

performance appraisal;

.

sharing and diffusion of information;

.

incentives; and

.

emphasis on promotions and development.

taken but do not ensure the future, and leading

indicators (unique to each company, e.g. the

employees' capabilities), that emphasise the

future because the business results depend on

them. They also distinguish between HR

performance drivers, key company capacities

related to people (e.g. productivity), and

enablers, which reinforce the drivers (e.g. a

system of incentives that stimulates a conduct).

Those authors stress that companies must

consider both the enablers and the performance

drivers, since the implementation of the

business strategy depends on both.

Management by competencies

Competency refers to actions which, by putting

into practice abilities, personality traits,

motivations and knowledge in an integrated

way, enable a task to be carried out successfully

(Levy-Leboyer, 1997; Spencer and Spencer,

1993). The added value of management by

competencies can be summed up as follows:

.

It permits its measurement and assessment.

.

All the HR practices can be organised

around competencies without having to use

different units for each practice.

.

It encourages flexibility in job descriptions.

.

It enables an integrated and coherent

management to be developed (coherence

between the departmental, business and job

competencies).

Methodology

Between November 2001 and January 2002, the

managers of 66 accommodation establishments

on the island of Gran Canaria (Spain) were

interviewed in person. The interviews were

semi-structured in order to analyse the content

of the HRM (instead of centring on whether an

HR practice was applied or not, as would be the

result of a self-administered questionnaire). This

permitted an in-depth diagnosis of the HRM and

of its approach, which is the really interesting

aspect (Guest, 1997). The average length of the

interviews was two and a quarter hours.

It can be seen that the model is really full of

suggestions and Becker and Huselid (1999), in

their in-depth study of five leading US

companies, named management by

competencies as one of the common practices.

Description of the sample

Of the 66 establishments, 77.2 per cent were

hotels of the following categories: five-star, 11.8

per cent; four-star, 43.1 per cent; three-star,

33.3 per cent; two-star, 11.8 per cent and 22.8

per cent were apartment complexes of the

following categories (unlike hotels, the

apartments on Gran Canaria are classified into

the following three categories, from lower to

higher: one-key, two-key and three-key):

three-key, 20 per cent; two-key, 53.3 per cent

and one-key 26.7 per cent. The activity of the

establishments was:

.

sun and beach tourism, 76.9 per cent;

.

city or urban tourism, 13.8 per cent; and

.

rural tourism, 9.2 per cent.

Management of intellectual capital

Intellectual capital refers to intellectual

material, knowledge, skills, intellectual

property, and experience that may be used to

create value (Steward, 1997). Within

intellectual capital, human capital stands out

(Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Becker et al.,

2001), and includes staff variables such as:

knowledge, satisfaction, motivation, leadership,

etc. The challenge of the human capital theory

lies in creating procedures for its management,

and, for example, Becker et al. (2001), when

explaining their specific method for HRM,

differentiated between two types of indicator

useful to management: lagging indicators

(mainly financial, e.g. profitability), which

reflect the consequences of decisions already

Of the companies, 43.9 per cent had an HR

department and the average size of workforce

was 146 employees.

60

Improving human resources management

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume 16 . Number 1 . 2004 . 59-64

Santiago Melian Gonzalez

Results

from the rest: working towards offering a

quality service (63.1 per cent of the

establishments) and improving customer

satisfaction and loyalty (60 per cent), which, as

can easily be deduced, require the support and

direct involvement of the employees. They were

also asked to name the main difficulties that

their establishments encountered and three

stood out: The low qualifications of their HR

(31 per cent), the competition (27.6 per cent),

and the shortage of workers (20.7 per cent).

The presentation of the results will be in the

form of answers to a series of questions. In that

way, the answers will be used to evaluate the

HRM of the establishments following the three

previously explained perspectives.

Do the managers believe that HR are

important?

The interviewees were asked to evaluate (with a

score of from one to five; one very little

importance; two slight importance; three

medium importance; four importance; and

five great importance) the importance of a

series of resources to the competitiveness of

their establishments. Of the 13 resources

evaluated, three directly related to HR were

placed among the top five: first, staff motivation

and involvement (mean: 4.59; std: 0.63),

fourth, management skills (mean: 4.41; std:

0.70), and fifth, staff capacity and knowledge

(mean: 4.41; std: 0.72). In addition, they were

asked to describe the actions that they

considered necessary to achieve a series of

business objectives. Table I shows the three

most named actions for each of the objectives,

all of which, except two, need actions that

involve the capacities and motivations of the

workforce.

Are the importance of HR and the need for

HRM reflected in the HR practices?

Given the answers to the two previous

questions, one would expect a high use of HR

practices, or best practices, for three reasons:

HR are important, they are necessary to

implement strategies, and the above-mentioned

difficulties.

However, 64 per cent of the establishments

had carried out training actions during 2001,

and 21.9 per cent of those had done so only for

obligatory topics (i.e. safety at work,

food-handling, and first-aid), so, in fact, only 50

per cent trained their workers in non-obligatory

matters. Moreover, the training of managers

and supervisors in management skills (i.e. staff

management and motivation) was also

uncommon (35.9 per cent).

Only 33.8 per cent used incentives as a

variable part of the salary. The most used

form of incentive was the productivity bonus

(72.7 per cent), followed by commission (18.2

per cent), attendance incentive (13.6 per cent)

and non-financial rewards (9.1 per cent). The

Do they need HRM?

The interviewees were asked to name the

strategic actions that they were implementing,

with the aim of seeing to what extent they

needed HR practices. Two actions stood out

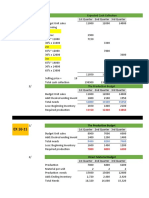

Table I Business objectives and actions

Objectives

Actions

High level of customer satisfaction

Friendly treatment (58.5 per cent); workers' efficiency (30.8 per cent)

and correct facilities (29.2 per cent)

Friendly treatment (72.1 per cent); quality of service (32.8 per cent)

and worker efficiency (23 per cent)

Information (52.9 per cent); advertising (21.6 per cent) and varied

offer (21.6 per cent)

Cost control (44.2 per cent); negotiations with suppliers (32.7 per

cent) and suitable size workforce (13.5 per cent)

Innovation (35.4 per cent); quality products (29.2 per cent) and good

service (25 per cent)

Professionalism (53.7 per cent); training (38.9 per cent) and quality

control (22.2 per cent)

High degree of customer loyalty

Optimum use of services

Low operating costs

High consumption in bar and restaurant

Quality of services

61

Improving human resources management

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume 16 . Number 1 . 2004 . 59-64

Santiago Melian Gonzalez

incentives were mainly aimed at managers and

supervisors (62.5 per cent), front-line staff

(31.3 per cent) and sales positions (18.8 per

cent).

Few establishments used formal performance

appraisal systems (35.9 per cent). The most

usual method was the customer survey (56.5

per cent), followed by the check-list (30.4 per

cent), the setting of targets (17.4 per cent),

conduct appraisal (8.7 per cent) and

timekeeping (4.3 per cent).

The most frequently used technique of staff

selection was an interview with the person

responsible for the vacant position (95.4 per

cent); however, typical HRM practices were

used very little: an interview with HR

department staff (35.4 per cent), psychological

tests (9.2 per cent), knowledge tests and asking

for references (4.6 per cent in both cases).

those with no such deoartment; 2 = 17.2;

p = 0.00);

made more use of management skills

training for their managers (55.2 per cent

compared with 20 per cent of those with no

HR department; 2 = 7.1, p = 0.01);

used more financial incentives (65.5 per

cent against 8.3 per cent, 2 = 21; p = 0.00);

and

appraised the employees' performance

more (50 per cent against 25 per cent and,

although the differences were not

completely significant, the trend was

noticeable: 2 = 3.3; p = 0.07).

Finally, the interviewees were asked to give the

year's business results a score of between one

and five, with one being very bad, two being

bad, three being normal, four being good and

five being very good. On checking these results

against the presence, or not, of an HR

department, there were no totally significant

differences, although the tendency was

noticeable (contingency coefficient = 0.30;

p = 0.09). So, the managers of the

establishments with HR departments tended to

describe the business results more positively.

Are HR indicators considered in

management?

The interviewees were asked which indicators

best reflected whether they were taking the right

decisions to achieve the establishment's

objectives. The three most named were:

occupancy (76.9 per cent), customer

satisfaction (67.7 per cent), and sales (47.7 per

cent), while the HR indicators were hardly

mentioned. When they were specifically asked

about those, the most common were:

absenteeism (49.2 per cent), staff turnover and

staff satisfaction (42.6 per cent in both cases,

although satisfaction was not reflected in a

quantitative indicator, but by perceptions), and

customer satisfaction (37.7 per cent).

Conclusions and practical implications

Based on the theoretical perspectives and the

results described, we now set out some

conclusions that contain practical implications

for improving HRM in accommodation

establishments. To do this, we use another set

of questions.

Were any benefits obtained from

management by competencies?

Not in most cases, since the majority did not

use the HR practices necessary for management

by competencies. Apart from that, the little

support that the strategies received from the

HR practices makes one think that the

advantages of this method were not taken into

account.

Is it enough that the managers have a

positive opinion about the role of HR in

companies for them to obtain the potential

benefits of HRM?

Although it is a good starting-point, favourable

beliefs about and attitudes towards the

potential of HR are not enough to develop a

high performance HRM. If we want a

workforce that adds value to our activity, the

managers' positive opinions are not enough. It

also requires an HR department in order to

establish HR practices that support

management strategy and maximise the

employees' contributions.

Is it important to have a formal HR

department?

The establishments with an HR department:

.

carried out more staff-training activities

(93.1 per cent as opposed to 40 per cent of

62

Improving human resources management

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume 16 . Number 1 . 2004 . 59-64

Santiago Melian Gonzalez

(e.g. profit per employee) are useful, but those

that really ensure that the right path is being

taken towards an objective (e.g. quality of

service) are the leading indicators (e.g. per cent

of employees with specific competencies; per

cent of favourable performance appraisals of

competencies essential to the strategy, etc.). If

the establishments had a set of leading

indicators (e.g. 5 per cent of cooks able to

prepare five or more typical regional menus),

they could take decisions about which HR

practices are the most suitable for implementing

the strategy (e.g. training the other cooks in

typical regional cuisine)

Which HR practices will enable the

potential benefits of HRM to be

maximised?

The positive influence of HRM is more

probable when a set of HR practices, coherent

with one another and related to business

objectives, is used. This complementariness has

synergetic effects. Therefore, it would not be

sufficient for a company with a strategy of

improving customer satisfaction to train its

employees in customer service skills; it should

also bear the customers' requirements in mind

when selecting its employees (e.g. selection

interviews and/or personality tests). Moreover,

it should appraise their performance using data

that reflect customer satisfaction (e.g.

satisfaction surveys) and/or by actions that

ensure high satisfaction (e.g. observation by

superiors) and/or performance objectives (e.g.

management by objectives); encourage a

conduct that influences customer satisfaction

(e.g. bonus or reward for performance targets)

and train supervisors how to lead and motivate

their work team to increase customer

satisfaction.

Must all the above be applied to the entire

workforce?

The key positions in the chain of value and in

implementing the strategy must be identified,

since they are the ones that require more

attention from HRM. Why is it mainly

managerial posts that receive incentives and not

the other jobs? It is a common occurrence in

companies, but the nature of its origin may be

institutional rather than have any real influence

on strategy. If that strategy is to improve

customer satisfaction, who directly contributes

more to that, a financial manager or the

restaurant waiters?

How does one design the function of HR in

the company?

Management by competencies permits the

architecture of HRM to be suitably structured.

Starting with the strategy (e.g. to improve the

quality of service by satisfying the customers'

demands), the establishment must specify

which competencies its departments need in

order to implement it (e.g. bars and restaurants:

offering menus typical of the local region) and

then design the HR practices that ensure that

the employees have the competencies necessary

at a strategy and/or department level (e.g. select

cooks who can prepare typical regional dishes;

teach cooks about the variety of local dishes;

appraise the performance and motivate by the

degree to which the objective of offering a

certain number of typical local menus is

achieved).

References

Becker, B.E. and Huselid, M.A. (1999), ``Overview: strategic

human resource management in five leading firms'',

Human Resource Management, Vol. 38 No. 4,

pp. 287-301.

Becker, B.E., Huselid, M.A. and Ulrich, D. (2001),

The HR Scorecard: Linking People, Strategy, and

Performance, Harvard Business School Press,

Boston, MA.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M.S. (1997), Intellectual Capital.

Realizing Your Company's True Value by Finding its

Hidden Brainpower, 1st ed., HarperCollins Publishers,

Philadelphia, PA.

Erstad, M. (2001), ``Commitment to excellence at the

Forte Hotel Group'', International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 13

No. 7, pp. 347-51.

Guest, D.E. (1997), ``Human resource management and

performance: a review and research agenda'', The

International Journal of Human Resource

Management, Vol. 3 No. 8, pp. 263-76.

Haynes, P. and Fryer, G. (2000), ``Human resources, service

quality and performance: a case study'', International

Why must HR leading indicators be

considered?

It is necessary, although difficult due to their

intangible nature, to consider human capital

indicators to assess whether business objectives

are being achieved. The traditional indicators

63

Improving human resources management

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

Volume 16 . Number 1 . 2004 . 59-64

Santiago Melian Gonzalez

Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management,

Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 240-8.

Huselid, M.A. (1995), ``The impact of human resource

management practices on turnover, productivity,

and corporate financial performance'', Academy

of Management Journal, Vol. 38 No. 3,

pp. 635-72.

Levy-Leboyer, C. (1997), Gestion de las competencias,

Ediciones Gestion 2000, Barcelona.

Mayer, K.J. (2002), ``Human resource practices and service

quality in theme parks'', International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 7 No. 4,

pp. 169-75.

Pfeffer, J. (1994), Competitive Advantage through People,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Pfeffer, J. (1998), The Human Equation, Harvard Business

School Press, Boston, MA.

Spencer, L.M. and Spencer, S.M. (1993), Competence at

Work: Models for Superior Performance, John Wiley,

Chichester.

Steward, T.A. (1997), La Nueva Riqueza de las

Organizaciones: EL Capital Intelectual, Granica,

Buenos Aires.

Further reading

Boyatzis, R. (1982), The Competent Manager: A Model for

Effective Managers, Wiley, New York, NY.

64

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Winnebago CaseDocument10 pagesWinnebago CaseYee Sook YingNo ratings yet

- Slide 3Document8 pagesSlide 3Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Digital Marketing Quiz UpdDocument4 pagesDigital Marketing Quiz UpdRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Winnebago CaseDocument10 pagesWinnebago CaseYee Sook YingNo ratings yet

- Drawing Old Traditioned HRDocument2 pagesDrawing Old Traditioned HRRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Transformational Leadership PDFDocument22 pagesTransformational Leadership PDFRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- American and British English ExerciseDocument1 pageAmerican and British English ExerciseHorizontes Do SaberNo ratings yet

- Jha2 170727161005Document16 pagesJha2 170727161005Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality ManagementDocument25 pagesInternational Journal of Contemporary Hospitality ManagementRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Key Stage 2 Sentence StartersDocument19 pagesKey Stage 2 Sentence StartersmirzabasithNo ratings yet

- Ijbm 06 2015 0092Document17 pagesIjbm 06 2015 0092Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Ergo AsiaDocument2 pagesErgo AsiaRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- JPBM 11 2014 0747Document15 pagesJPBM 11 2014 0747Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Jrim 06 2014 0038Document26 pagesJrim 06 2014 0038Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Speaking Sample Interview Hometown JobsDocument1 pageSpeaking Sample Interview Hometown Jobswaheed_iiuiNo ratings yet

- GJDocument58 pagesGJKishore ChakravarthyNo ratings yet

- SOM497 - Business Policy & Strategy: Basic Concepts of Strategic ManagementDocument15 pagesSOM497 - Business Policy & Strategy: Basic Concepts of Strategic ManagementRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Ijsrp p5113Document6 pagesIjsrp p5113Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Criteria for Evaluating PR EffectivenessDocument15 pagesCriteria for Evaluating PR EffectivenessRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Strategy FormulationDocument50 pagesStrategy FormulationRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- IELTS Writing TasksDocument64 pagesIELTS Writing TasksRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Halloween Conversation Questions: Costumes, Candy, Movies & MoreDocument1 pageHalloween Conversation Questions: Costumes, Candy, Movies & MoreRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Total English Placement Test: Choose The Best Answer. Mark It With An X. If You Do Not Know The Answer, Leave It BlankDocument6 pagesTotal English Placement Test: Choose The Best Answer. Mark It With An X. If You Do Not Know The Answer, Leave It BlankMỹ Dung PntNo ratings yet

- Criteria for Evaluating PR EffectivenessDocument15 pagesCriteria for Evaluating PR EffectivenessRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business PlanDocument28 pagesAssignment On Business PlanShantanu Das85% (62)

- Business Plan Hair Salon 2Document23 pagesBusiness Plan Hair Salon 2Rosa Willis100% (1)

- ESL Dictation Exercises Food VocabularyDocument6 pagesESL Dictation Exercises Food VocabularyRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Slide 4Document6 pagesSlide 4Rosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Indian Nonveg Recipes (9xmobi - Com)Document20 pagesIndian Nonveg Recipes (9xmobi - Com)bhuppi0802No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Quantitative Demand AnalysisDocument25 pagesChapter 3 Quantitative Demand AnalysisRosa WillisNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Principles of Marketing 16th Edition Kotler Solutions ManualDocument29 pagesPrinciples of Marketing 16th Edition Kotler Solutions Manualkimviolet7ydu100% (24)

- Institute of Hospitality Ebooks 2013Document21 pagesInstitute of Hospitality Ebooks 2013PusintuNo ratings yet

- Internal Audit Check Sheet Ok 2016Document11 pagesInternal Audit Check Sheet Ok 2016manttupandeyNo ratings yet

- Strategy ImplementationDocument30 pagesStrategy ImplementationThabiso DaladiNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Latin AmericaDocument18 pagesMicrosoft Latin AmericadjurdjevicNo ratings yet

- Innovative Leadership in Modern HRDocument7 pagesInnovative Leadership in Modern HRHamza RanaNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Roles of A Manager in OrganizationDocument5 pagesTop 10 Roles of A Manager in OrganizationANUPAM KAPTINo ratings yet

- Guide To Edge Management SolutionsDocument13 pagesGuide To Edge Management Solutionssaba0707No ratings yet

- Fillable Document Master List Template Form NasaDocument1 pageFillable Document Master List Template Form Nasadabicum69420No ratings yet

- Advanced Work PackagesDocument24 pagesAdvanced Work Packagescfsolis100% (1)

- Case Study: (GROUP 5)Document3 pagesCase Study: (GROUP 5)Jay Castro NietoNo ratings yet

- Software Engineering Question BankDocument3 pagesSoftware Engineering Question BankNALLAMILLIBALASAITEJAREDDY 2193118No ratings yet

- Kaist BTM BrochureDocument14 pagesKaist BTM BrochureMagda P-skaNo ratings yet

- by Nitin SinghDocument6 pagesby Nitin SinghAditi GhaiNo ratings yet

- Kế toán quản trịDocument88 pagesKế toán quản trịHà Mai VõNo ratings yet

- PGMP One Stop Shop Version 1.0 (Sample Copy)Document81 pagesPGMP One Stop Shop Version 1.0 (Sample Copy)Jogender Saini0% (1)

- Benefits: Employees TPI-theoryDocument2 pagesBenefits: Employees TPI-theorylollaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to HRM ConceptsDocument49 pagesIntroduction to HRM Conceptsraazoo19No ratings yet

- AE 24 Business Analysis ProjectsDocument23 pagesAE 24 Business Analysis ProjectsJyle Mareinette ManiagoNo ratings yet

- Brand Equity of Dettol Brand Equity of Dettol: Rohit Chugh Kankesh Sanjeev Chanika NagarajDocument32 pagesBrand Equity of Dettol Brand Equity of Dettol: Rohit Chugh Kankesh Sanjeev Chanika NagarajrohitchughNo ratings yet

- Employment Pass - Immigration GuidelinesDocument16 pagesEmployment Pass - Immigration GuidelinesMotea AlomariNo ratings yet

- Project Communications ManagementDocument40 pagesProject Communications ManagementLouis CentenoNo ratings yet

- IB Scotia477BR CoverletterDocument3 pagesIB Scotia477BR Coverletterphuongdpl2s4518No ratings yet

- Introduction to Assurance, Auditing and Related ServicesDocument4 pagesIntroduction to Assurance, Auditing and Related ServicesmymyNo ratings yet

- RPA in Financial Services Infographic by RapidValueDocument1 pageRPA in Financial Services Infographic by RapidValuewawawa1No ratings yet

- Demand Management Techniques for Service FirmsDocument23 pagesDemand Management Techniques for Service FirmsJerrie GeorgeNo ratings yet

- SCM Fall 17 - 3 - Purchasing ManagementDocument22 pagesSCM Fall 17 - 3 - Purchasing ManagementMYawarMNo ratings yet

- ERP Configuration Using GBI Phase II Handbook (A4) en v3.3Document102 pagesERP Configuration Using GBI Phase II Handbook (A4) en v3.3Adi SulistyoNo ratings yet

- Inventory ControlDocument23 pagesInventory ControlKomal RatraNo ratings yet

- Maniego, Chantelle Kyle TDocument15 pagesManiego, Chantelle Kyle TPatrick LanceNo ratings yet