Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How The Brain and Music Theory Encourage Plagiarism - The Atlantic

Uploaded by

Erica BoydOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How The Brain and Music Theory Encourage Plagiarism - The Atlantic

Uploaded by

Erica BoydCopyright:

Available Formats

9/19/2016

HowtheBrainandMusicTheoryEncouragePlagiarismTheAtlantic

Musicians Are Wired to Steal Each Other's Work

The rules of Western music limit originality in songsand the human brain doesnt

want it, anyway.

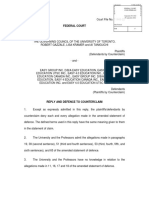

Robert Plant, lead singer of Led Zeppelin, performing at a concert in Morocco

Youssef Boudlal / Reuters

PHILIP BALL

SEP 14, 2016

SCIENCE

TEXT SIZE

Like The Atlantic? Subscribe to the Daily, our free weekday email newsletter.

Email

SIGN UP

It dont matter what you do, / Hey, hey its all up to you.

You have to be of a certain age to appreciate the irony in this permissive paean,

sung in 1977 by Randy California (n Wolfe), the guitarist of the rock band Spirit.

http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/09/musicplagiarism/499985/

1/7

9/19/2016

HowtheBrainandMusicTheoryEncouragePlagiarismTheAtlantic

Earlier this year, a trustee for the late Wolfes estate implied that it matters very

much what you do, attempting to sue the rock legends Led Zeppelin for stealing

Randys music. The lawsuit, heard in June, alleged that Zeppelins Jimmy Page

lifted the famous ngerpicked acoustic opening of Stairway to Heaven (1971)

from Spirits 1968 instrumental Taurus.

Led Zeppelin are no strangers to such accusations. Their iconic Whole Lotta

Love, from their 1969 album Led Zeppelin II, brought a whole lotta trouble when

the blues artist Willie Dixon realized that it used some of the lyrics from his 1962

song You Need Love. On the same album, Bring It On Home borrowed from

another of Dixons songs (this time with an identical title), while The Lemon

Song was partly derived from Howlin Wolfs Killing Floor.

This doesnt exhaust the accusations of musical theft that Page and songwriting

partner Robert Plant have faced. Part of the problem, says the music psychologist

Richard Hass, of Philadelphia University, was that, particularly in their early days,

Led Zeppelin had the habit, time-honored in blues music, of jamming around a

known tune to construct new songs. Maybe they just got a bit lazy about hiding the

origins, Hass says. Their main problem, though, was probably making enough

money that a plagiarism lawsuit becomes worthwhile: Stairway to Heaven is

estimated to have earned Page and Plant almost $60 million.

It looks all the worse to see a bunch of white guys getting rich by drawing on the

works of lesser known and sometimes impoverished black artistsunfortunately

another time-honored tradition in popular music. Led Zeppelin reached an out-ofcourt settlement for the borrowings from Dixon in Whole Lotta Love, as well as

lucrative settlements with a branch of Chess Records for the other legal suits

brought in response to Led Zeppelin II.

Is similarity enough to qualify as plagiarism?

http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/09/musicplagiarism/499985/

2/7

9/19/2016

HowtheBrainandMusicTheoryEncouragePlagiarismTheAtlantic

But the latest case concerning Stairway was dismissed by the court. While Page

testied that the band used to jam to another of Spirits songs from their

eponymous 1968 debut album, he denied ever having heard Taurus until

suggestions of the similarities began to appear online. You can judge for yourself

from several juxtapositions on Youtube. To my ear, theres certainly a similarity to

the musical fragments.

But is similarity enough to qualify as plagiarism? The question is more complicated

than it might seem.

You might imagine the issues arent so dierent from those in other artistic elds,

especially literature. Charges of stealing someones ideas, as the historians Michael

Baigent and Richard Leigh claimed of Dan Browns The Da Vinci Code, are murky.

But if you can put the words side by side and show the overlap, as happened for

allegations against How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life, Kaavya

Viswanathans much-hyped 2006 debut novel, the case is pretty clear. So surely

you can do the same comparison with notes and chords, right?

But in music its not that simple. The stringing together of notes and chords is

bound by rules far more constraining than those that govern linguistic grammar

and semantics. In pretty much all of Western music outside of the 20th-century

avant-garde, only a limited number of sequences of tones and chords sound

right, while others seem wrong. So its very likely that, if you come up with a

sequence of chords that sounds good, someone else will have already used it.

Crudely speaking, two chords t together well if theyor the scales on which

theyre basedshare many notes in common. Countless songs use a shift from C

major to A minor, for instance (think of the rst lines of Leonard Cohens

Hallelujah), because the respective scales are closely related. The relationships

between chords can be represented as a kind of spatial map of harmonic space,

showing which are close together and which are far apart. Typically, Western tonal

music uses chord sequences that make only small steps in this space from one

chord to the next. The paths are very limited, especially in the strongly formulaic

and melodic forms of pop and rock. So expecting songwriters to avoid all echoes of

http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/09/musicplagiarism/499985/

3/7

9/19/2016

HowtheBrainandMusicTheoryEncouragePlagiarismTheAtlantic

other songs is a little like putting someone inside a maze and telling them to nd an

original way out.

As we listen to music ... it gets literally imprinted in the

neurons of the part of the brain ... that processes harmony.

One of the key defenses in the Stairway to Heaven case was that Pages opening

chord structurea descending minor chromatic progressionis very old, dating

back at least to the baroque era. (It also appears, Page attested, in Chim Chim

Cher-ee, from the movie Mary Poppins.) And the chord progression in the songs

raucous nale, A minor to F major via G major, is a textbook example of harmonic

proximity that has appeared in countless other rock and pop songs, including Bob

Dylans All Along the Watchtower.

This harmonic map of chord relationships becomes so mentally ingrained as we

listen to music that, at least for musically experienced listeners, it gets literally

imprinted in the neurons of the part of the brain (within the prefrontal cortex) that

processes harmony. No wonder we stick so closely to its pathways.

Melodies, toothe tune of a songare highly rule-bound. Melodies in pop,

classical, and non-Western music all tend to use predominantly small steps

between the pitches of successive notes. They also tend to rise and then descend

again, in a kind of arc. At the simplest level, this gives us the rather banal melodic

trajectories of nursery rhymes. Pop musicians are often scarcely much more

inventive: It always seemed to me that the tunes crooned by Morrissey, of the

Smiths, do not dare to venture beyond about a three-note range. But the truth is

that, if you want to pen a hummable melody, there arent many options in any case.

Purely in statistical terms, then, youd expect that the rules of pleasant harmony

and melody will end up generating rather homogeneous bodies of music. Pop and

rock mostly juggle with an extremely small range of artistic choices, and often

genius and innovation is a matter of putting old wine in new bottles.

http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/09/musicplagiarism/499985/

4/7

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Case Mate v. Velvet Caviar - ComplaintDocument17 pagesCase Mate v. Velvet Caviar - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Coleman vs. California Yearly Meeting of Friends ChurchDocument2 pagesColeman vs. California Yearly Meeting of Friends ChurchFaye Cience BoholNo ratings yet

- Estate of Jolley Case SummaryDocument11 pagesEstate of Jolley Case SummaryKay CeeNo ratings yet

- 05 Asian Terminals vs. PhilamDocument1 page05 Asian Terminals vs. PhilamJanWacnang100% (1)

- United States v. Ronald Thomas Bohle, 475 F.2d 872, 2d Cir. (1973)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Ronald Thomas Bohle, 475 F.2d 872, 2d Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CENTURY INDEMNITY COMPANY v. ANHEUSER-BUSCH, INC. ComplaintDocument22 pagesCENTURY INDEMNITY COMPANY v. ANHEUSER-BUSCH, INC. ComplaintACELitigationWatchNo ratings yet

- Ousley v. Ward, 10th Cir. (2002)Document4 pagesOusley v. Ward, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SC Annual 12Document122 pagesSC Annual 12The Supreme Court Public Information Office100% (1)

- Germann & Co. vs. Donaldson, Sim & Co. power of attorney validityDocument3 pagesGermann & Co. vs. Donaldson, Sim & Co. power of attorney validityCampbell HezekiahNo ratings yet

- 56 Metropol Vs SambokDocument3 pages56 Metropol Vs SambokCharm Divina LascotaNo ratings yet

- Dispute over the probate of Paciencia Regala's willDocument11 pagesDispute over the probate of Paciencia Regala's willLaw SSCNo ratings yet

- Saludo, Jr. V CADocument50 pagesSaludo, Jr. V CACathy BelgiraNo ratings yet

- Warren Consolidated School Sex Assault LawsuitDocument22 pagesWarren Consolidated School Sex Assault LawsuitMLive.comNo ratings yet

- Prabhudayal Agarwal v. Saraswati BaiDocument7 pagesPrabhudayal Agarwal v. Saraswati BaiMayankSahuNo ratings yet

- Worcester v. Worcester Consolidated Street R. Co., 196 U.S. 539 (1905)Document8 pagesWorcester v. Worcester Consolidated Street R. Co., 196 U.S. 539 (1905)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Non-Filing ITRDocument1 pageAffidavit of Non-Filing ITRHazel-mae Labrada100% (1)

- CAse Digest Obligations of VendeeDocument1 pageCAse Digest Obligations of Vendeejetzon2022No ratings yet

- Pe 610 Waiver Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesPe 610 Waiver Reflection Paperapi-459743145No ratings yet

- Corporate Insolvency Law Exam NotesDocument167 pagesCorporate Insolvency Law Exam NotesBrandon Tee100% (3)

- Section 43 (A) in A Vacuum: Cleaning Up False Advertising in An Unfair Competition MessDocument14 pagesSection 43 (A) in A Vacuum: Cleaning Up False Advertising in An Unfair Competition MessNew England Law ReviewNo ratings yet

- Hudson Meridian Construction Lawsuit. Summit Vs Hudson MeridianDocument65 pagesHudson Meridian Construction Lawsuit. Summit Vs Hudson MeridianJohn CarterNo ratings yet

- Testimony - Kelley, SunnyDocument4 pagesTestimony - Kelley, SunnymikekvolpeNo ratings yet

- Lease Telecom MD3536 Sprint DouglassHighDocument26 pagesLease Telecom MD3536 Sprint DouglassHighParents' Coalition of Montgomery County, MarylandNo ratings yet

- Stella Liebeck Vs Mcdonalds 1290108622 Phpapp02Document47 pagesStella Liebeck Vs Mcdonalds 1290108622 Phpapp02Muhammad Farrukh RanaNo ratings yet

- Delfin Tan V BenoliraoDocument2 pagesDelfin Tan V BenoliraoRoms RoldanNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument2 pagesUntitledapi-131262037No ratings yet

- 2002-2003 Corporation Law Bar QuestionsDocument2 pages2002-2003 Corporation Law Bar QuestionsKim CajucomNo ratings yet

- UofT Reply & Defence To CC StampedDocument15 pagesUofT Reply & Defence To CC StampedHoward KnopfNo ratings yet

- Macondray Vs Providence InsuranceDocument4 pagesMacondray Vs Providence InsuranceCheezy Chin100% (1)

- Court Strikes No-Build Buffer Zone PolicyDocument2 pagesCourt Strikes No-Build Buffer Zone PolicykhalkhalbdNo ratings yet