Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 J2008 - Fate and Free Will in The Bhagavadgītā

Uploaded by

budimahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

0 J2008 - Fate and Free Will in The Bhagavadgītā

Uploaded by

budimahCopyright:

Available Formats

Religious Studies

http://journals.cambridge.org/RES

Additional services for Religious Studies:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

Fate and free will in the Bhagavadgītā

Arvind Sharma

Religious Studies / Volume 15 / Issue 04 / December 1979, pp 531 - 537

DOI: 10.1017/S0034412500011719, Published online: 24 October 2008

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0034412500011719

How to cite this article:

Arvind Sharma (1979). Fate and free will in the Bhagavadgītā. Religious Studies, 15, pp

531-537 doi:10.1017/S0034412500011719

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/RES, IP address: 138.251.14.35 on 21 Mar 2015

Rel. Stud. 15, pp. 531-537

ARVIND SHARMA

Lecturer in Religious Studies, University of Queensland

FATE AND FREE WILL IN THE BHAGAVADGITA

The issue of free will versus fate can be analysed in three ways in relation to

the Bhagavadgita: (1) by focusing on those verses of the Glta which address

themselves to this question; (2) by focusing on the figure of Arjuna himself

who, as will be shown, crystallizes around his person the issue of free will and

fate; and (3) by focusing on the Kauravas who are similarly involved in the

issue.

11

There are two verses of the Bhagavadgita which seem to address themselves

to this issue. They appear successively. Unfortunately the interpretation of

one of these verses is problematical1 or at least has been made to appear so.2

This is the 14th verse of the xvmth chapter of the Bhagavadgita. It may be

translated thus:

The (material) basis, the agent too,

And the instruments of various sorts,

And the various motions of several kinds,

And Fate, as the fifth of them.3

The next verse, more free from commentarial divergencies than the

previous one, may also be cited here:

With body, speech, or mind, whatever

Action a man undertakes,

Whether it be lawful or the reverse,

These are its five factors.4

If the interpretation accorded to these verses by Franklin Edgerton, with

which the present writer is in agreement, is accepted, the outcome of events

is visualized not in terms ofjust two factors — free will or fate — but in terms of

five factors: (1) material (natural?) basis (adhisthdna); (2) doer (kartd);

(3) instruments of various sorts (karana)); (4) various motions or, if you

please, efforts of several kinds {prthak cestd); (5) fate (daivam). Thus basis,

1

W. Douglas P. Hill, The Bhagavadgita (Oxford University Press, 1969), pp. 204-5.

2

Franklin Edgerton, The Bhagavadgita (New York: Harper & Row, 1964), p. 102.

3 4

Ibid. p. 84. Ibid.

0034-4125/79/2828-2801 $1.50 © 1979 Cambridge University Press

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

532 ARVIND SHARMA

doer, instruments, efforts and fate - these five decide the outcome of an

undertaking. Fate is an element - but is not the only one. The outcome seems

to be the result of both free will as represented by the doer and his efforts, and

fate acting in a given environment involving given instruments.

in

The case of Arjuna seems to be more complicated, as Krsna seems to suggest

at times that Arjuna possesses free will in the matter of engaging or not

engaging in battle and at times that he does not really possess any free will.

He seems to suggest that Arjuna has free will in this respect when, near the

end of the Glta, he tells Arjuna:

Thus to thee has been expounded the knowledge

That is more secret than the secret, by Me;

After pondering on it fully,

Act as thou thinkest best.1

And Arjuna too, by declaring:

I stand firm, with doubts dispersed;

I shall do Thy word.2

seems to admit to the fact that he had the option to fight or not to and that,

in accordance with what Krsna has said he chooses to fight. Thus in Krsna's

statement and Arjuna's response - both quoted above - free will seems to be

involved or implied.

There are, however, verses which, at least on the face of it, seem to suggest

that fighting on the part of Arjuna is predestined. These are uttered just

before Arjuna is told to 'act as he pleases':

If thy mind is on Me, all difficulties

Shalt thou cioss over by My grace;

But if thru egotism thou

Wilt not heed, thou shalt perish.

If clinging to egotism

Thou thinkest ' I will not fight!',

Vain is this thy resolve;

(Thine own) material nature will coerce thee.

Son of KuntI, by thine own natural

Action held fast,

What thru delusion thou seekest not to do,

That thou shalt do even against thy will.

Of all beings, the Lord

In the heart abides, Arjuna,

Causing all beings to turn around

(As if) fixed in a machine, by his magic power.3

1 2 3

Ibid. p . 90. Ibid. p . 91. Ibid. p . 89.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

FATE IN THE BHAGAVADGITA 533

These verses clearly sound deterministic. It is helpful to recognize that they

speak of two kinds of determinism - a natural one and a supernatural one.

Bhagavadgita xvm.59-60 speak of a natural determinism. These verses

may be paraphrased in terms of the saying 'character is destiny', though

understood in a slightly different sense from the usual. The very nature, the

character of Arjuna as a warrior, will impel him willy-nilly in the direction of

fighting.1 Because of his martial character he is destined to fight. Therefore

he should not hesitate but proceed to fight.

The case for supernatural determinism is less clear than that for natural

determinism.

Bhagavadgita xvm.61-2 seem to speak of a supernatural determinism, if

Krsna is identified with the Lord abiding in the heart. The message seems to

be that men are mere puppets carrying out the wish of God and it has

already been determined by God that the Kauravas should die in Bhaga-

vadgita xi.32-4. As against this it may be pointed out that in these verses

Krsna does not say 'seek refuge in M e ' as he does later, but tells Arjuna to

seek refuge in that {tarn) Isvara in Bhagavadgita xvm .61-2. Besides, although

the Kauravas are predestined to die (and this in itself illustrates an element of

predeterminism in the Gita) Krsna does not say that they are destined to be

killed by Arjuna. They are destined to die but it is not entirely clear whether

they are destined to die by Arjuna's hand (though this seems to be implied).

It could then be maintained on the presumption that the Gita is essentially

deterministic that the Kauravas were destined to die 'supernaturally' and

Arjuna destined to kill them 'naturally'. But this involves assuming that the

Gita does preach determinism.2

If determinism in the case of Arjuna is seen as proceeding only from natural

factors, as proceeding from his character, then it can be argued that Krsna's

statements have a persuasive rather than coercive force. He does not want to

coerce Arjuna but tries to persuade Arjuna by pointing out that Arjuna's own

nature will coerce Arjuna to fight (and perhaps if he does not - which he does

not say - torment him for not having fought). This statement on the part of

Krsna could well be Krsna's way of persuading Arjuna that four out of the

five elements determining an outcome are present in the existing situation -

only his effort is now wanting to accomplish the outcome. On this view the

fact that at the end of this section of verses Krsna tells Arjuna to do as you

please signifies that free will is still involved. It may also be argued, however,

that Krsna's statement is pro forma.

1

Also see Bhagavadgita in. 33 for an anticipation of this argument.

2

If the distinction drawn above between the two kinds of determinisms is obliterated, then the

teaching of the Gita is reduced to a kind of ontological determinism in which everything is the will

of God. This position approximates the Islamic doctrine oijabr in the most severe form, and even

in Islam some kind of a theoretical or practical via media had to be adopted (see R. C. Zaehner,

ed., The Concise Encyclopedia of Living Faiths [Boston: Beacon Press, 1959], p. 200).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

534 ARVIND SHARMA

The discussion, at this point, however, is complicated by the fact that

throughout the Gita. Arjuna is (i) exhorted to act (e.g. 11.3.37; xi.33, etc.)

and (2) to act in a particular way. Both of these, prima facie, involve an

element of free will. Thus when Arjuna is exhorted to get rid of his ahankdra

(xvm. 16.17) or to employ his buddhi (11.39.50),* obviously some freedom of

will is employed. But what is given by one hand the Gita. may be seen as, at

least in part, taking away by the other if it be maintained that Arjuna's

ksatriyahood will impel him to act (XVIII . 59.60) and that his ksatriyahood in

itself is part and parcel of a compelling cosmic pattern (xvin. 40-8). This,

however, brings up a situation in which a scholar's judgement of the evidence

as distinguished from the evidence itself may be involved. In a complex text

like the Gita, evidence may not always speak for itself, for then one ends up

with a plain contradiction. For instance, xvm.59 clearly suggests that

Arjuna is predestined to fight but XVIII . 63 indicates that Arjuna possesses free

choice.2 Now herein we seem to be involved in a situation wherein the nature

of the relationship between expression and intention is in question. Krsna's

statements could be looked upon in two ways: he knows Arjuna is going to

fight and so alludes to his free choice knowing full well what he must choose

or he wants Arjuna to fight and to impel him to do so he states that

Arjuna must anyway, as a sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is clear that the

latter interpretation allows for more free will than the former but one cannot

be sure which interpretation is the 'correct one'.

IV

In the case of the Kauravas, their destruction is fully predestined, as has

already been pointed out. Arjuna then, in effect, is being asked to act so that

their destiny may befall the Kauravas. The Kauravas are destined to die but

Arjuna is not destined to kill them in that sense - he is destined to kill them,

if at all, because he will be impelled by his warrior nature to fight and there-

fore to kill them. 3

But as to the predestined nature of the destruction of the Kauravas (and

1

In these contexts the words ahavkara and buddhi do not seem to possess the technical Sankhyan

connotations.

2

Unfortunately the sequence in which these verses appear does not help in resolving the issue

because of the simultaneous presence in the Hindu lore of traditions according priority to the former,

as well as the latter. Thus the MImaihsa doctrine of purvapurvabaliyastvam accords priority to earlier

statements while the grammatical doctrine of uttarottaraballyastvam to the latter. 1 am indebted for

this clarification to Miss Alaka Hejib of McGill University.

3

One is reminded here of the following Marxian paradox: 'Why then, if the decay and collapse

of capitalism are inevitable, should it be necessary to form organizations and discipline cadres to

hasten its downfall? What purpose would be served by revolutionary agitation if the historical

outcome would be no different? Orthodox Marxists have normally hedged this question, arguing

that militant organization acts as a midwife to hasten social change. The rejoinder, however, fails to

dispose of the methodological problem' (William J. Barber, A History of Economic Thought [Baltimore:

Penguin Books, 1967] p. 162).

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

FATE IN THE BHAGAVADGITA 535

indeed of some other warriors as well Bhagavadgita leaves little room for

doubt. Arjuna foresees their destruction in the cosmic vision of Krsna in

Bhagavadgita xi. 26-8:

And Thee yonder sons of Dhrtarastra,

All of them, together with the hosts of kings,

Bhlsma, Drona, and yonder son of the charioteer (Karna) too,

Together with our chief warriors likewise.

Hastening enter Thy mouths,

Frightful with tusks, and terrifying;

Some, stuck between the teeth,

Are seen with their heads crushed.

As with many water-torrents of the rivers

Rush headlong towards the single sea,

So yonder heroes of the world of men into Thy

Flaming mouths do enter.1

Moreover, Krsna himself clearly states that their end is predestined, in

Bhagavadgita xi.32-4:

I am Time (Death), cause of destruction of the worlds, matured

And set out to gather in the worlds here.

Even without thee (thy action), all shall cease to exist,

The warriors that are drawn up in the opposing ranks.

Therefore arise thou, win glory,

Conquer thine enemies and enjoy prospered kingship;

By Me Myself they have already been slain long ago;

Be thou the mere instrument, left-handed archer!

Drona and Bhlsma and Jayadratha,

Karna too, and the other warrior-heroes as well,

Do thou slay, (since) they are already slain by Me; do not hesitate!

Fight! Thou shalt conquer thy rivals in battle.2

v

In chapter xvi Arjuna and the Kauravas are discussed together in terms of the

Gita's well-known classification of two types of beings in the world, the daiva

and the dsura? Now Krsna says of the dsura that:

These wicked ones, I constantly hurl

Into demoniac wombs alone.4

Now several interesting points emerge from a consideration of the material

in this chapter. The first is that Arjuna is clearly identified as belonging to the

daiva or divine type (xvi. 5):

Be not grieved: to the divine lot

Thou art born, son of Pandu.6

1 2 8

Franklin Edgerton, op, cit. pp. 57-8. Ibid. p. 58. Bhagavadgita xvi. 6.

4 5

Frankling Edgerton, op. cit. p. 78. Ibid. p. 76.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

ARVIND SHARMA

But the Kauravas are never clearly identified as belonging to the demoniac

types, though one could possibly infer such an identification. The other

interesting aspect of the chapter is that while it enumerates numerous

qualities of the 'good' (xvi. 1-3) and 'bad' types (xvi.4.7-20), it mentions

people as being ' born' to that lot (abhijdta). Is then one's assignment to the

divine or demoniac lot qualitative or congenital? The answer is not entirely

clear.

VI

Thus one conclusion suggested by the analysis in general and specially by the

immediately preceding one is that the Gita. opts for predeterminism. How-

ever, both the text and the context seem to render such a blanket statement

vulnerable. Another possible conclusion is that the Gita. never quite makes up

its mind. A more detailed discussion, however, suggests clearer contours, if

not yet a definite conclusion.

It is not entirely clear whether Arjuna's participation in the war would be

an exercise of free will on his part, or is fated. It may be noted, however, that

even if he is destined to fight this is the result of his nature or character, not

of his past karma or prdrabdha. Since traditionally in Hindu thinking destiny is

associated with past karma1 this is a significant point.2 Although the Bhaga-

vadgita seems to recognize generally both free will and fate as affecting an

outcome specifically, in the case of the Mahabharata war, it may be seen as

regarding the death of the Kauravas as destined. On the question of the

fact or degree of Arjuna's predestination, it is hard to be completely certain,

though on balance some free will on Arjuna's part appears to be involved. The

overall position of the Gita on the issue of the role of free will and fate in

shaping the future is perhaps best summed up as follows.

There is ' no fate, circumstance or even which in the last analysis we do not

or have not created for ourselves (i.e. ourselves in relationship with others) '. 3

But this is neither 'an optimistic or a pessimistic view, and certainly not a

pessimistic one. We are today what we have made ourselves all through the

past, and we shall be tomorrow what we have been made by the past

together with our present attitudes'. 4 But in this process one faces a plasticine

future and one should note that 'the relation between future and present

may be as significant as between past and present. ' It doth not yet appear

what we shall be', and the present may be what it is, so that a future may be

what it shall be (and what on the deeper levels it already is) '.5 This aspect of

1

The use of the word karma in Bhagavadglta xvm. 60 could be misleading in this context. Note

that the word karmand has to be construed with the adjective svabhavajena and not with some hypo-

thetical or parenthetical purvajanmand.

2

T. M. P. Mahadevan, Outlines of Hinduism (Bombay: Chetana Ltd, i960), pp. 60-1.

3

Raynor C.Johnson, TTie Imprisoned Splendour (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1953), p . 173.

4 6

Ibid. Ibid. p. 174.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

FATE IN THE BHAGAVADGITA 537

the Gita - that it looks at free will and fate not as part of a past-present

continuum but as part of a present-future continuum - is the most remark-

able aspect of its treatment of free will and fate.1

It seems possible to suggest, then, that the various conclusions suggested

earlier, namely, that the Gita opts for predeterminism or that it never quite

makes up its mind about the issue, can be seen as fragments of a larger mosaic

provided by the trichotomy of Karma with kriyamdna or dgdmi karma;

sancita karma and prdrabdha. In terms of this trichotomy, the death of the

Kauravas has become prdrabdha but participation in battle by Arjuna is yet

sancita karma, which is being provided with the cutting edge of dgdmi or

kriyamdna karma by Krsna's pep-talk to render it fully operational or prd-

rabdha, something which in Krsna's view Arjuna could, should and would do.

1

Bhagavadglta iv. 5 and xv. 8 seem to imply this general belief in the doctrine of Karma. Also

see S. Radhakrishnan, The Bhagavadglta (London: George Allen and Unwin, i960), p. 356.

http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 21 Mar 2015 IP address: 138.251.14.35

You might also like

- 0 J2004 - Calling Krsna's Bluff Non-Attached Action in The Bhagavadgītā PDFDocument24 pages0 J2004 - Calling Krsna's Bluff Non-Attached Action in The Bhagavadgītā PDFbudimah100% (1)

- From Alexandria to Baghdad: The Transmission of AstrologyDocument35 pagesFrom Alexandria to Baghdad: The Transmission of Astrologyalaa alaaNo ratings yet

- HinduPad Padshahi 1925 EditionDocument327 pagesHinduPad Padshahi 1925 EditionAnkit Akki UpadhayayNo ratings yet

- Ayvali KiliseDocument118 pagesAyvali KiliseBurak SıdarNo ratings yet

- Abhinavagupta's Life and WorksDocument10 pagesAbhinavagupta's Life and WorksRajinder MahindrooNo ratings yet

- Review For Indus Script DictionaryDocument1 pageReview For Indus Script DictionaryNilesh OakNo ratings yet

- Death of Sanskrit Sheldon PollockDocument35 pagesDeath of Sanskrit Sheldon PollockMatsyendranatha100% (1)

- Arun Murthi Mulavidya ControversyDocument29 pagesArun Murthi Mulavidya ControversyShyam SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Comet Observation in Ancient India: RN Iyengar-JGSIDocument6 pagesComet Observation in Ancient India: RN Iyengar-JGSINarayana Iyengar100% (2)

- Conger, George P. - Did India Influence Early Greek Philosophies - Philosophy East and West, 2, 2 - 1952 - 102-128Document28 pagesConger, George P. - Did India Influence Early Greek Philosophies - Philosophy East and West, 2, 2 - 1952 - 102-128the gathering50% (2)

- A Note On The Schoyen Copper Scroll Bact PDFDocument6 pagesA Note On The Schoyen Copper Scroll Bact PDFanhuNo ratings yet

- Iranian Gods in IndiaDocument14 pagesIranian Gods in IndiaArastoo MihanNo ratings yet

- Gaina Sutras 01Document428 pagesGaina Sutras 01Rob Mac HughNo ratings yet

- Identification of Asmaka - Aryabhata and Jain TraditionDocument15 pagesIdentification of Asmaka - Aryabhata and Jain Traditionhari18100% (1)

- Ramayana Summary by Valmiki and NaradaDocument49 pagesRamayana Summary by Valmiki and NaradaRamamurthy NatarajanNo ratings yet

- Satapatha Brahmana Part 2Document519 pagesSatapatha Brahmana Part 2Lathika MenonNo ratings yet

- Krishna & Arjun NamesDocument4 pagesKrishna & Arjun Namesns_ranaNo ratings yet

- The Theory of The Sacrifice in The YajurvedaDocument6 pagesThe Theory of The Sacrifice in The YajurvedaSiarhej SankoNo ratings yet

- Land of Tamils Loges War AnDocument35 pagesLand of Tamils Loges War Anwalter2099175No ratings yet

- Appaya DikshitaDocument15 pagesAppaya DikshitaSivasonNo ratings yet

- Strength of Ram's ArmyDocument2 pagesStrength of Ram's ArmyArun Kumar UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Who Are VellalasDocument56 pagesWho Are VellalasDr.Kanam100% (2)

- J. N. Farquhar, The Fighting Ascetic of IndiaDocument22 pagesJ. N. Farquhar, The Fighting Ascetic of Indianandana11No ratings yet

- Topaz Khubayb Vessel Spec Sep2016Document9 pagesTopaz Khubayb Vessel Spec Sep2016Jym GensonNo ratings yet

- The Ekavratya Indra and The SunDocument32 pagesThe Ekavratya Indra and The Sunporridge23No ratings yet

- BAHUBALI BiographyDocument15 pagesBAHUBALI Biographyinnocentshah100% (1)

- Shulman Tamil BiographyDocument19 pagesShulman Tamil BiographyVikram AdityaNo ratings yet

- The Development of Vedic CanonDocument93 pagesThe Development of Vedic CanonrudrakalNo ratings yet

- Avatāra - Brill ReferenceDocument8 pagesAvatāra - Brill ReferenceSofiaNo ratings yet

- A History of Dharmasastra Vol I - KaneDocument804 pagesA History of Dharmasastra Vol I - KanensvkrishNo ratings yet

- The Ajivikas PT 1 BaruaDocument90 pagesThe Ajivikas PT 1 Baruamr-normanNo ratings yet

- Axe Bow Concept - Gelling 2005Document44 pagesAxe Bow Concept - Gelling 2005haujesNo ratings yet

- (Sir William Meyer Lectures) K. N. Dikshit - Prehistoric Civilization of The Indus Valley-Indus Publications (1988)Document87 pages(Sir William Meyer Lectures) K. N. Dikshit - Prehistoric Civilization of The Indus Valley-Indus Publications (1988)Avni ChauhanNo ratings yet

- The Womb of Tantra Goddesses Tribals and Kings inDocument18 pagesThe Womb of Tantra Goddesses Tribals and Kings inSiddharth TripathiNo ratings yet

- Venvaroha Computation of Moon Madhava of ADocument23 pagesVenvaroha Computation of Moon Madhava of ARodolfo Tinoco VeroneseNo ratings yet

- 15 Verses Critical EditionDocument7 pages15 Verses Critical EditionKevin SengNo ratings yet

- Vedic Gods and The Sacrifice (Jan Gonda)Document35 pagesVedic Gods and The Sacrifice (Jan Gonda)茱萸褚No ratings yet

- 1831 Mysore Peasant UprisingDocument97 pages1831 Mysore Peasant UprisingcoolestguruNo ratings yet

- Bronner and Shulman A Cloud Turned Goose': Sanskrit in The Vernacular MillenniumDocument31 pagesBronner and Shulman A Cloud Turned Goose': Sanskrit in The Vernacular MillenniumCheriChe100% (1)

- The Sārārthacandrikā Commentary On The Trikā Aśe A by Śīlaskandhayativara PDFDocument7 pagesThe Sārārthacandrikā Commentary On The Trikā Aśe A by Śīlaskandhayativara PDFLata DeokarNo ratings yet

- Indo-Aryan Research Encyclopedia Explores Epic Mythology DatesDocument0 pagesIndo-Aryan Research Encyclopedia Explores Epic Mythology DatesGreenman52No ratings yet

- Mechanical Contrivances and Dharu Vimanas of Samarangana SutradharaDocument6 pagesMechanical Contrivances and Dharu Vimanas of Samarangana SutradharaSushil KarkhanisNo ratings yet

- The Early Western Satraps and The Date of The Periplus / by David W. MacDowallDocument13 pagesThe Early Western Satraps and The Date of The Periplus / by David W. MacDowallDigital Library Numis (DLN)No ratings yet

- Narada SmritiDocument78 pagesNarada SmritiSachin MakhijaNo ratings yet

- Saka ERADocument22 pagesSaka ERAChinmay Sukhwal100% (1)

- The Agganna SuttaDocument10 pagesThe Agganna SuttaMauricio Follonier100% (1)

- Saraswati The Lost Vedic RiverDocument3 pagesSaraswati The Lost Vedic RiverAna MendonçâNo ratings yet

- PDF Created With Fineprint Pdffactory Pro Trial VersionDocument223 pagesPDF Created With Fineprint Pdffactory Pro Trial Versiontariqbhat22294No ratings yet

- Chittoor Mana - Chittoor Swaroopam - History With ZamorinsDocument15 pagesChittoor Mana - Chittoor Swaroopam - History With ZamorinsRajan Chittoor100% (1)

- (1896) Journal of The Asiatic Society of Bengal 65Document454 pages(1896) Journal of The Asiatic Society of Bengal 65Gill BatesNo ratings yet

- AMARNATH Ji YatraDocument2 pagesAMARNATH Ji YatraLet Us C KashmirNo ratings yet

- Lord of VaikuntaDocument140 pagesLord of VaikuntaMurari RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- Dayeakut'iwn in Ancient ArmeniaDocument22 pagesDayeakut'iwn in Ancient ArmeniaRobert G. BedrosianNo ratings yet

- Culture of Ancient IndiaDocument18 pagesCulture of Ancient IndiaudayNo ratings yet

- Aitareya Aranyaka - EngDocument139 pagesAitareya Aranyaka - EngAnonymous eKt1FCD100% (1)

- The Birth of the War-God A Poem by KalidasaFrom EverandThe Birth of the War-God A Poem by KalidasaNo ratings yet

- Bhagavad GitaDocument14 pagesBhagavad GitaGeorge Stanboulieht67% (3)

- Bhagavad Gita Commentary-FullDocument272 pagesBhagavad Gita Commentary-FullSkyWalkerr6No ratings yet

- Gita For AwakeningDocument300 pagesGita For AwakeningLokesh KhuranaNo ratings yet

- "The Person Who, Having Abandoned All Desires (Sarva N Karma N), Acts Without Desire (Nisspr - Hah.), Without ADocument14 pages"The Person Who, Having Abandoned All Desires (Sarva N Karma N), Acts Without Desire (Nisspr - Hah.), Without ASyed ArmanNo ratings yet

- Bhagavad Gita For The Physician PDFDocument9 pagesBhagavad Gita For The Physician PDFbudimahNo ratings yet

- History of Sanskrit LiteratureDocument12 pagesHistory of Sanskrit LiteraturebudimahNo ratings yet

- Leadership Paradigm of Bhagavad-GitaDocument9 pagesLeadership Paradigm of Bhagavad-GitabudimahNo ratings yet

- J2011 - The Bhagavadgita, Philosophy Versus HistoricismDocument12 pagesJ2011 - The Bhagavadgita, Philosophy Versus HistoricismbudimahNo ratings yet

- J2016 - Orthodoxy and Dissent in Hinduism's Meditative Traditions A Critical Tantric PoliticsDocument17 pagesJ2016 - Orthodoxy and Dissent in Hinduism's Meditative Traditions A Critical Tantric PoliticsbudimahNo ratings yet

- Two Concepts of ViolenceDocument12 pagesTwo Concepts of Violenceflicky_gNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Asian-Indian Hindus Toward End-Of-Life CareDocument5 pagesAttitudes of Asian-Indian Hindus Toward End-Of-Life CarebudimahNo ratings yet

- J2008 - Nietzsche As Europe's Buddha' and Asia's Superman'Document19 pagesJ2008 - Nietzsche As Europe's Buddha' and Asia's Superman'budimahNo ratings yet

- Sūk Ma and The Clear and Distinct Light The Path To Epistemic Enhancement in Yogic and Cartesian MeditationDocument27 pagesSūk Ma and The Clear and Distinct Light The Path To Epistemic Enhancement in Yogic and Cartesian Meditationbudimah100% (1)

- J2018 - The Subject Is FreedomDocument22 pagesJ2018 - The Subject Is FreedombudimahNo ratings yet

- J2015 - Role of Self-Managing Leadership in Crisis Management An Empirical Study On The Effectiveness of RajayogaDocument24 pagesJ2015 - Role of Self-Managing Leadership in Crisis Management An Empirical Study On The Effectiveness of RajayogabudimahNo ratings yet

- J2015 - Trans-Personal & Psychology of The Vedic System, Healing The Split Between Psychology & SpiritualityDocument8 pagesJ2015 - Trans-Personal & Psychology of The Vedic System, Healing The Split Between Psychology & SpiritualitybudimahNo ratings yet

- Jprosriding2017 - Numbers With PersonalityDocument8 pagesJprosriding2017 - Numbers With PersonalitybudimahNo ratings yet

- J2013 - Ayurveda Between Religion, Spirituality, and MedicineDocument12 pagesJ2013 - Ayurveda Between Religion, Spirituality, and MedicinebudimahNo ratings yet

- J2015 - Realm Between Immanent and TranscendentDocument17 pagesJ2015 - Realm Between Immanent and TranscendentbudimahNo ratings yet

- J2010 - Suturing The Body Corporate (Divine and Human) in The Brahmanic TraditionsDocument23 pagesJ2010 - Suturing The Body Corporate (Divine and Human) in The Brahmanic TraditionsbudimahNo ratings yet

- 0 J2013 - Sankhya (Jnana) The Yoga of KnowledgeDocument10 pages0 J2013 - Sankhya (Jnana) The Yoga of KnowledgebudimahNo ratings yet

- 0 J2013 - Discerning The Mystical Wisdom of The Bhagavad Gita and John of The CrossDocument24 pages0 J2013 - Discerning The Mystical Wisdom of The Bhagavad Gita and John of The CrossbudimahNo ratings yet

- The Cultural Connotation of Dharma in The Bhagavad GītāDocument5 pagesThe Cultural Connotation of Dharma in The Bhagavad GītāIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Overlapping Elements Between Law and Bhagavad GitaDocument16 pagesOverlapping Elements Between Law and Bhagavad GitabudimahNo ratings yet

- Mmy 2 PDFDocument39 pagesMmy 2 PDFVladimir NabokovNo ratings yet

- 0 J2014 - Formulating A New Three Energy Framework of Personality For Conflict Analysis and Resolution Based On Triguna Concept of Bhagavad GitaDocument14 pages0 J2014 - Formulating A New Three Energy Framework of Personality For Conflict Analysis and Resolution Based On Triguna Concept of Bhagavad GitabudimahNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI)Document3 pagesInternational Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI)inventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- 0 J2016 - Empirical Model On Self Growth - Based On Bhagavat GitaDocument8 pages0 J2016 - Empirical Model On Self Growth - Based On Bhagavat GitabudimahNo ratings yet

- 0 J2014 - Reading Hesse's Siddhartha Through The Lens of The Bhagavad Gita in The Present Day Context PDFDocument3 pages0 J2014 - Reading Hesse's Siddhartha Through The Lens of The Bhagavad Gita in The Present Day Context PDFbudimahNo ratings yet

- GitaDocument69 pagesGitaAnonymous IwqK1NlNo ratings yet

- 0 J2002 - Mind' in Indian Philosophy PDFDocument11 pages0 J2002 - Mind' in Indian Philosophy PDFbudimahNo ratings yet

- 0 J2013 - Purpose of Spirituality On Performance PDFDocument5 pages0 J2013 - Purpose of Spirituality On Performance PDFbudimahNo ratings yet

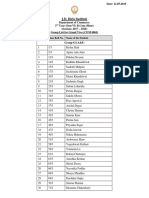

- Zone I 1-1-44Document44 pagesZone I 1-1-44Prasanna KumarNo ratings yet

- GPSC 1 2 Main Exam Question Paper GS 2017 PDFDocument4 pagesGPSC 1 2 Main Exam Question Paper GS 2017 PDFकमलेशकुमारNo ratings yet

- 2 6 137 317 PDFDocument8 pages2 6 137 317 PDFSalman KhanNo ratings yet

- STAFF TRANSFER LISTDocument804 pagesSTAFF TRANSFER LISTcool_spNo ratings yet

- Hanuman Mantra For JobDocument1 pageHanuman Mantra For JobKalaiarasan KrishnarajNo ratings yet

- Resources BollywoodDocument12 pagesResources Bollywood24x7emarketing67% (3)

- J.D. Birla Institute: SL - No. Class Roll No. Name of The StudentDocument9 pagesJ.D. Birla Institute: SL - No. Class Roll No. Name of The StudentdhjubgdfubgNo ratings yet

- Do Do ShadiDocument86 pagesDo Do ShadiDesi Rocks100% (1)

- Lessons From The Life of Srila Narottam Das ThakurDocument9 pagesLessons From The Life of Srila Narottam Das ThakurGaura PremiNo ratings yet

- Analog Ias Institute: Prelims Test Series 2019Document10 pagesAnalog Ias Institute: Prelims Test Series 2019Subh sNo ratings yet

- Baby NamesDocument7 pagesBaby Nameskiran_kkk1No ratings yet

- 09 Chapter 3Document65 pages09 Chapter 3sanshlesh kumar100% (1)

- Buddhist Art in AsiaDocument282 pagesBuddhist Art in Asiaخورشيد أحمد السعيدي100% (3)

- Participants' ListDocument17 pagesParticipants' ListSharuk KhanNo ratings yet

- Airtel ListDocument2 pagesAirtel ListRavi AyNo ratings yet

- 8GML BS Chemistry 2020 PDFDocument138 pages8GML BS Chemistry 2020 PDFShoaib GondalNo ratings yet

- Franchisee Counters in KSRTC Jurisdiction in Karnataka StateDocument12 pagesFranchisee Counters in KSRTC Jurisdiction in Karnataka StateKishore KumarNo ratings yet

- Vajra Songs From The Ocean of Definitive MeaningDocument88 pagesVajra Songs From The Ocean of Definitive MeaningRishi Jindal100% (1)

- Projects 230608Document6 pagesProjects 230608api-3757629No ratings yet

- List of Shareholders Regrading Unclaimed Dividends /unclaimed SharesDocument54 pagesList of Shareholders Regrading Unclaimed Dividends /unclaimed SharesChaudhary Muhammad Suban TasirNo ratings yet

- Hall For GateDocument16 pagesHall For GateGagan KandraNo ratings yet

- Colourful Cities of North IndiaDocument2 pagesColourful Cities of North Indiaanand mishraNo ratings yet

- Mod. Indian SculpturesDocument34 pagesMod. Indian Sculpturesneeru sachdevaNo ratings yet

- KishoreSatsangPravesh EngDocument107 pagesKishoreSatsangPravesh EngYogesh PatelNo ratings yet

- Topic: Nationalism in India: Submitted by Submitted ToDocument56 pagesTopic: Nationalism in India: Submitted by Submitted ToSarthak Kushwaha0% (1)

- Name Address1 Address2 City Phone Mobile: AccountantsDocument3 pagesName Address1 Address2 City Phone Mobile: AccountantsmadhavNo ratings yet

- Befikre': Vaani Kapoor To Romance Ranveer Singh inDocument6 pagesBefikre': Vaani Kapoor To Romance Ranveer Singh inManishNo ratings yet

- List of Rare BooksDocument3 pagesList of Rare BooksSathis KumarNo ratings yet

- Akash EnglishDocument2 pagesAkash EnglishSai Malavika TuluguNo ratings yet

- Current AffairsDocument116 pagesCurrent AffairsKesava Sai GaneshNo ratings yet