Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Poems of Love and War - Excerpt

Uploaded by

tvphile1314100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

2K views8 pagesTamil Sangam Poetry

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTamil Sangam Poetry

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

2K views8 pagesPoems of Love and War - Excerpt

Uploaded by

tvphile1314Tamil Sangam Poetry

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

— Sores

©. Poems of Love and War> >

‘Although cultural influences spread throughout the indian subconti-

ent, south India remained politically independent of the north until

the British conquest. South Indians spoke languages of an entirely

different family, Dravidian, than north india. The oldest of these lan-

guages, Tamil, was regularized about 250 BCE and Is less influenced

by Sanskrit than any other Indian language. It produced a classical

literature during the period from 150 BCE to 250 CE, of which several

anthologies of poems survive. There are about 150 million speakers

of Dravidian languages today.

Indian civilization took a different form in the Dravidian kingdoms.

The Indus Valley civilization may have spoken a Dravidian language

and thus may have influenced Vedic society as well as south India.

The Indus Valley script has never been deciphered, however, and

the extent fo which Dravidian culture originated in the Indus Valley is

uncertain, In any case, agriculture did not appear in south India until

centuries after the end of the Indus Valley civilization, and records of

the Tamils date from hundreds of years later stil

There are no reliable historical records from the period in which

the poems were composed, but the surviving texts tell us much about

the society. The poems are primarily secular and deal with love, war,

governance, trade, and mourning, South india was divided into three

kingdoms, the Pandyas, the Colas, and the Cheras. The region had

lo major extemal threats. Classical Tamil poetry is called “Sangam”

Poetry because it was later anthologized by a literary academy that

called itself sangam (trom the name for a Buddhist community of

4“

POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR 45

monks, or sangha). The academy claimed that two ancient sangams

that preceded it had produced the poems. There is no historical evi-

dence for the existence of these earlier academies, and the poems

themselves clearly were composed by many different authors at cit-

ferent times and places. The fact that the poems were compiled at

a later date suggests that more literature may not have found its way

into the compilations and is lost.

Tamil poetics are described in the treatise Tolkappiyam, written in

‘about the year 300. Early Tamil poetry is predominantly secular and is

divided into two categories, akam (interior, or subjective, pronounced

“cham'’) and puram (exterior, or objective). Love poems fall nto the first

category, war into the second. The primary elements of Tamil poetics

are location (landscapes) and time (both the seasons of the year and

the six parts of the day). The five landscapes of akam poetry are hills,

forests, farmland, seashore, and wasteland. Akam poems are also

shaped by "native elements," of relations between humans and nature,

‘nd "human elements,” usually the stages of a love affair. Puram poetry

has seven landscapes, corresponding fo the phases of combat: catile

raiding, invasion, siege, pitched battle, victory, death, and praise of

kings. (The latter two were not considered suitable for poetry.) Within

this framework the Sangam poets created a moving literature.

In the first poem, for example, the kurifici and the mountain scene

clearly mark this as a poem about lovers meeting, Their union is not

described but only alluded to by the scene of the bees making honey

from the flowers of the kurifci plant (which comes to flower only atter

twelve years). The poem zooms from cosmic abstractions about the

speaker's love to the mountain slopes, the bees, and the flower itself,

suggesting her progression from idealized feeling to physical intimacy.

All this is accomplished in a few lines. The remainder of the akam

Poems ate also about lovers meeting, except for the last, which is

from the genre palai (wasteland), which describes the lovers’ journey

through wilderness.

The puram poems here describe warfare and its consequences. The

last of the puram poems, “king Killiin Combat,” is based on a histori-

cal incident that would have been well known fo those who heard the

poem. The Cola king Killi wagered his kingdom on a wrestiing match

with a rival. The first part of the poem describes the frantic moves of a

cobbler who must finish a cot for his wife, who by custom must deliver

their baby on it.The situations are parallel: the movements of both are

45 POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR

skiliful.f the cobbler succeeds, the child will be born on the cot and

they will rejoice; if King Kill succeeds, the kingcom will be reborn and.

the people will rejoice. The labumam is not a symbol of a mood as it

would be in an akam poem, but simply the emblem of a clan.

The final poem is exceptional, since most of the poems have few

religious references. It a late classical poem of praise to Tirumal, a

god of the forests who was later identified with Vishnu. In this poem the

classical form is adapted to the new devotional (bhakti) Hinduism.

The translator of these poems, A.K. Ramanujan (1929-1993), was

one of India’s greatest modern poets as well as a noted scholar of

Dravidian languages. These pieces are not only accurate translations

of the letter and spitit of the originals, but works of elegant poetry in

their own right. In these and other collections, Ramanujan brought to

lite one of the world's great literatures.

The absence of early historical records for south India has led to

much fanciful speculation about the prehistory of Tamil speakers. The

site htip://archaeologyindia.com, incomplete at the time of his writing,

attempts to illustrate as much of the early evidence as possible

Questions

1. What to you are the most striking similarities and differences

between the okam and puram poems?

2. Dothe very stylized references to location, season, and time of

day detract from the message of an akam poem or enhance

i? Ate there similarities in other love poems you have read?

3. The images of warfare in the puram poems are radically

different from those in the Bhagavad Gita. Are there ur

themes in the two genres?

Po eos

Poems of Love and War

A.K. Ramanujan, sel. and trans.,

Poems of Love and War from the Eight Anthologies

and the Ten Long Poems of Classical Tamil

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1985),

pp.5, 16, 17, 22-23, 63, 115-117, 120, 123, 179, 218

POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR 47

Akam Poems

What She Said

Bigger than earth, certainly,

higher than the sky,

‘more unfathomable than the waters

is this love for this man

of the mountain slopes

where bees make rich honey

from the flowers of the kurifici

that has such black stalks.

Tevakulattar

Kuruntokai 3

What He Said

Asa little white snake

with lovely stripes on its young body

troubles the jungle elephant

this slip of a girl

her teeth like sprouts of new rice

her wrists stacked with bangles

troubles me.

Catti Natanar

Kuruntokai 119

What She Said

Only the thief was there, no one else.

And if he should fie, what can [ do?

There was only

a thin-legged heron standing

on legs yellow as millet stems

and looking

for lampreys

in the running water

when he took me

Kapilar

Kuruntokai 25

48 POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR

What Her Girl Friend Said to her

‘Their throats glittering like blue sapph

tail feathers splendid,

the peacocks gather

with sweet calls,

dancers skilled in slow-beat rhythms.

But you don't play anymore

like those peacocks

with your girl friends

in the long deep streams,

‘wearing wreaths of blue lily

with petals like eyes,

tresses flaring

as they dance.

Your heart is anxious,

you're lonely, stricken

‘with pallor.

Now, what shall I say to Mother

if she should notice changes

and ask for reasons?

Tknow,

our man from the mountain top

where long silver waterfalls shiver

in the wind

like white banners

borne high on elephants

with trappings on their brow,

T know

he has brought you these pangs.

But what shall [ say to Mother

iff she asks

Maturai Marutanilandicanar

Akandniiru 358

What He Said

The heart, knowing

no fear,

POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR 49

has left me

to go and hold my love

but my arms,

left behind,

cannot take hold.

So what's the use?

In the space between us,

murderous tigers

roar like dark ocean waves,

circling

in O how many woods

between us

and our arms’ embrace

Allir Nanmullait

Kuruntokai 237

Puram Poems

Harvest of War

Great king,

you shield your men from ruin.

so your victories, your greatnes

are byword

Loose chariot wheels

lie about the battleground

with the long white tusks of

bull-elephants,

Flocks of male ¢

cat carrion

with their mates

Headless bodies

dance about

before they fall

to the ground.

Blood glows,

like the sky before nightfall,

in the red center

of the battlefield.

Demons dance there.

‘And your kingdom

30. POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR

is an unfailing harvest

of victorious wars.

Kappiyarrukkappiyanar

on Kalatikaykkanni Narmutice@ral

Patirruppatiu 35,

A King’s Last Words,

in jail, before he takes his life

Ifa child of my clan should die,

ifitis bon dead,

a mere gob of flesh

not yet human,

they will put it to the sword,

to give the thing

a warrior’s death,

Will such kii

bring a son into this world

to be kept now

like a dog at the end of a chain,

who must beg.

because of a fire in the belly,

for a drop of water,

and lap up a beggar’s drink

brought by jailers,

friends who are not friends?

(Céraman Kanaikkal Irumporai

Purananairu 74

The Horse Did Not Come Back

‘The horse did not come back,

his horse did not come back.

All the other horses have come back.

‘The horse

of our good man,

who was father in our house

to alittle son

with a tuft of hair

like a plume on a steed,

it did not come back.

POEMS OF LOVE AND WAR St

Has it fallen now,

his horse

that bore him through battle,

has it fallen

like the great tree

standing at the meeting place

of two rivers?

Purananiiru 273,

King Killi in Combat

With the festival hour close at hand,

his woman in labor,

sun setting behind pouring rains,

the needle in the cobbler’s hand

is ina frenzy

stitching thongs for a cot

swilter, far swifter,

were the tackles of our lord

‘wearing garlands of laburnum,

as he wrestled with the enemy

come all the way

to take the land.

Caittantaiyar:

on PorvaikkOpperunar Kili

Purandniiru 82

Religious Poem

Tirumat

In fire, you are the heat.

In flowers, you are the scent.

Among stones, you are the diamond.

In words, you are truth.

‘Among virtues, you are love.

In a warrior’s wrath, you are the strength.

In the Vedas, you are the secret.

Of the elements, you are the frst,

In the scorching sun, you are the light.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Bonnie Marranca Interview Maria Irene Fornes 1978Document7 pagesBonnie Marranca Interview Maria Irene Fornes 1978tvphile1314No ratings yet

- Amruta Patil's Kari - Review by Neel MukherjeeDocument5 pagesAmruta Patil's Kari - Review by Neel Mukherjeetvphile1314100% (1)

- Study Questions - Man - To - Send - RaincloudsDocument1 pageStudy Questions - Man - To - Send - Raincloudstvphile1314No ratings yet

- Complacency and ConvergenceDocument9 pagesComplacency and Convergencetvphile1314No ratings yet

- George Steiner - Tragedy - ReconsideredDocument15 pagesGeorge Steiner - Tragedy - Reconsideredtvphile1314No ratings yet

- Passage To America by Ayyappa PanikerDocument3 pagesPassage To America by Ayyappa Panikertvphile1314No ratings yet

- BOOKLAND English Honours 1st Sem SyllabusDocument2 pagesBOOKLAND English Honours 1st Sem Syllabustvphile1314No ratings yet

- Bonnie Marranca 2019 - Thinking About Maria Irene FornesDocument3 pagesBonnie Marranca 2019 - Thinking About Maria Irene Fornestvphile1314No ratings yet

- Hyder - Ship of SorrowsDocument3 pagesHyder - Ship of Sorrowstvphile1314No ratings yet

- Tejero - Interview With AmbaiDocument4 pagesTejero - Interview With Ambaitvphile1314No ratings yet

- SRF Faruqi On Faruqi 2013Document23 pagesSRF Faruqi On Faruqi 2013tvphile1314100% (1)

- Fefu and Her Friends: Written by María Irene FornésDocument12 pagesFefu and Her Friends: Written by María Irene Fornéstvphile1314No ratings yet

- Bonnie Marranca 1984 - The Real Life of Maria Irene FornesDocument7 pagesBonnie Marranca 1984 - The Real Life of Maria Irene Fornestvphile1314No ratings yet

- South Indian History Reading ListDocument3 pagesSouth Indian History Reading Listtvphile1314No ratings yet

- Anuja Madan Review of Picturing Childhood - Youth in Transnational ComicsDocument5 pagesAnuja Madan Review of Picturing Childhood - Youth in Transnational Comicstvphile1314No ratings yet

- Ferro Luzzi - Facing Death in Modern Tamil LiteratureDocument12 pagesFerro Luzzi - Facing Death in Modern Tamil Literaturetvphile1314No ratings yet

- R E Asher - Vaikom Muhammad BasheerDocument19 pagesR E Asher - Vaikom Muhammad Basheertvphile1314100% (1)

- Geeta Patel - Ismat-Chughtai PDFDocument11 pagesGeeta Patel - Ismat-Chughtai PDFtvphile131450% (2)

- A R Venkatachalapathy - Triumph of Tobacco - The Tamil ExperienceDocument7 pagesA R Venkatachalapathy - Triumph of Tobacco - The Tamil Experiencetvphile1314No ratings yet

- Melissa Croteau - Ancient Aesthetics and Current Conflicts - Indian Rasa Theory and Vishal Bharadwaj's HaiderDocument12 pagesMelissa Croteau - Ancient Aesthetics and Current Conflicts - Indian Rasa Theory and Vishal Bharadwaj's Haidertvphile1314No ratings yet

- Ghosh, Avijit 2012 - Bhojpuri Cinema - Between Yesterday and TomorrowDocument12 pagesGhosh, Avijit 2012 - Bhojpuri Cinema - Between Yesterday and Tomorrowtvphile1314100% (1)

- Faiz Raaz e Ulfat RomanDocument1 pageFaiz Raaz e Ulfat Romantvphile1314No ratings yet

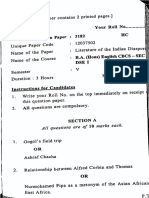

- Literature of The Indian Diaspora - Question PaperDocument2 pagesLiterature of The Indian Diaspora - Question Papertvphile1314No ratings yet

- The Chandravati Ramayana - A Story of Two WomenDocument6 pagesThe Chandravati Ramayana - A Story of Two Womentvphile13140% (1)

- Anoj Itra: Old Stone Mansion, The Pond and ApocalypseDocument4 pagesAnoj Itra: Old Stone Mansion, The Pond and Apocalypsetvphile1314No ratings yet

- Kalidasa BibliographyDocument53 pagesKalidasa Bibliographytvphile1314No ratings yet

- Sadan Jha - IESHR - Visualising A Region - Phaniswarnath Renu and The Archive of The 'Regional-Rural' in The 1950sDocument37 pagesSadan Jha - IESHR - Visualising A Region - Phaniswarnath Renu and The Archive of The 'Regional-Rural' in The 1950stvphile1314No ratings yet

- Bapsi Sidhwa InterviewDocument9 pagesBapsi Sidhwa Interviewtvphile1314No ratings yet

- Jonathan Bate - The Case For The Folio',2007Document69 pagesJonathan Bate - The Case For The Folio',2007tvphile1314No ratings yet

- Seetha Vijayakumar - Kannagi's Plucked Breast - A Gender PerspectiveDocument6 pagesSeetha Vijayakumar - Kannagi's Plucked Breast - A Gender Perspectivetvphile1314No ratings yet