Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Herpes Viruses PDF

Uploaded by

Elena TraciOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Herpes Viruses PDF

Uploaded by

Elena TraciCopyright:

Available Formats

PERSPECTIVE Sixth Disease and the Ubiquity of Human Herpesviruses

Sixth Disease and the Ubiquity of Human Herpesviruses

Charles Prober, M.D.

Related article, page 768

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is the cause of the appearance of herpesviruses include oral secretions

sixth clinically distinct exanthematous disease of (for HSV-1, EBV, CMV, HHV-6, and HHV-7), genital

childhood. Measles virus, erythrogenic group A secretions (HSV-2, CMV, and HHV-6), urine (CMV),

streptococci, and rubella virus are the causes of the mononuclear cells (CMV, HHV-6, and HHV-7), and

first three diseases, and parvovirus B19 is the cause breast milk (CMV and HHV-7). Host immunity in-

of the fifth disease. The origin of the fourth classic fluences both the likelihood of reactivation and the

childhood illness, formerly referred to as Dukes’ severity of clinical illness. In general, the greater the

disease, is controversial. Some medical historians degree of immune impairment, the more substan-

believe that it probably represented misdiagnosed tial the consequences of herpesvirus reactivation.

cases of rubella or scarlet fever, rather than a distinct Given the high incidence of all herpesvirus in-

illness. fections (except HHV-8 infection) and the biologic

HHV-6 is so named because it was the sixth hu- phenomenon of latency, the ubiquity of these virus-

man herpesvirus to be identified. This family of es is readily apparent. In the United States, infec-

large DNA viruses includes eight known human tions caused by HSV-1 begin in infancy, and at least

pathogens. In addition to HHV-6, these include her- 50 percent of young adults have been infected. In-

pes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), herpes simplex vi- fections caused by HSV-2 begin with the onset of

rus type 2 (HSV-2), varicella–zoster virus (VZV), sexual activity, and an estimated 25 percent of U.S.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), adults have contracted infection. EBV infections in-

human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7), and human herpes- crease in frequency during adolescence, and most

virus 8 (HHV-8) (see table). Herpesviruses have of the population is infected by middle age. CMV is

several common features. Each roughly spherical the most common cause of congenital infection,

virion is 150 nm to 200 nm in diameter and con- with 1 percent of all newborns infected; postnatal

sists of a 100-nm icosahedral nucleocapsid con- infections begin to occur within the first few weeks

taining a core of linear, double-stranded DNA viral of life, and by early adulthood approximately 50 per-

genome, spooled around a nucleoprotein central cent of the population is seropositive. Before the

mass. The nucleocapsid is surrounded by a layer of development of a vaccine for VZV, chickenpox (VZV

amorphous, asymmetrically distributed material infection) occurred in virtually all people by late

(tegument), which, in turn, is encased by a lipid- childhood; the epidemiology of infection has been

containing envelope with multiple glycoprotein changing since the introduction of universal vacci-

protrusions. nation.

The most important biologic property shared by In this issue of the Journal, Zerr et al. (pages

all herpesviruses is their ability to establish a per- 768–776) note that approximately three quarters of

sistent state following primary infection. This ca- children have been infected with HHV-6 by two

pacity means that once a person has become infect- years of age. Data from other studies suggest that

ed with a herpesvirus, he or she is forever susceptible infection with HHV-7 has a similar epidemiologic

to periodic viral reactivation. Reactivation results in pattern. Clearly, herpesvirus infections are omni-

the emergence of transmissible virus. The site of vi- present, and at any given time, a substantial pro-

ral latency varies. Even in the absence of signs or portion of the population is shedding one or more

symptoms of infection, common sites of periodic of these infectious agents, maintaining the chain of

transmission and the high prevalence of infection.

Dr. Prober is a professor of pediatrics and of microbiolo-

Even though the majority of infections caused by

gy and immunology at Stanford University School of herpesviruses are asymptomatic or mild (see figure),

Medicine and scientific director of the Glaser Pediatric the morbidity attributable to these agents remains

Research Network — both in Stanford, Calif. substantial. Furthermore, death due to herpesvirus-

n engl j med 352;8 www.nejm.org february 24, 2005 753

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH - MAIN on August 12, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERSPECTIVE Sixth Disease and the Ubiquity of Human Herpesviruses

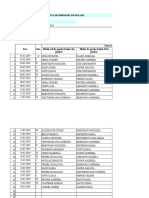

Human Herpesviruses.

Approximate

Seroprevalence

among Young Common Site of Mode of

Virus U.S. Adults (%) Infections Persistence Transmission

Herpes simplex virus 50 Herpes labialis, herpes Neuronal cells, espe- Contact with secretions,

type 1 whitlow, herpetic ker- cially trigeminal especially oral

atitis, herpes simplex ganglia

encephalitis

Herpes simplex virus 25 Herpes genitalis, herpes Neuronal cells, espe- Contact with secretions,

type 2 proctitis, neonatal cially sacral gan- especially genital

herpes glia

Varicella–zoster virus 100 Chickenpox, herpes Neuronal cells, espe- Contact with infected skin

zoster (shingles) cially posterior lesions; respiratory

root ganglia route for chickenpox

Epstein–Barr virus 75 Infectious mononucleo- B lymphocytes Contact with oral secre-

sis, prolonged fever, tions, blood, or trans-

multiorgan manifes- planted organs

tations

Cytomegalovirus 50 Infectious mononucleo- Monocytes, macro- Contact with oral or genital

sis, prolonged fever phages secretions, urine,

breast milk, blood, or

transplanted organs

Human herpesvirus 6 100 Febrile illness, roseola T lymphocytes Contact with oral secre-

tions

Human herpesvirus 7 100 Febrile illness, roseola T lymphocytes Contact with oral secre-

tions or breast milk

Human herpesvirus 8 <10 Kaposi’s sarcoma Not established Contact with bodily secre-

tions

es is a major issue for the ever-increasing popula- types of cancer is well established (e.g., EBV has a

tion of immunocompromised persons. HSV-1 in- role in Burkitt’s lymphoma in Africa, nasal pharyn-

fections cause herpes labialis, whose manifestations geal carcinoma, and post-transplantation lympho-

range from periodic mild discomfort accompanied proliferative disorder, and HHV-8 has a role in Ka-

by a few perioral vesicles to a severe infection neces- posi’s sarcoma). In contrast, the role of these

sitating hospitalization. HSV-1 is also responsible viruses in several chronic diseases, such as multi-

for most cases of herpetic whitlow and other cuta- ple sclerosis and the chronic fatigue syndrome,

neous eruptions (e.g., herpes gladiatorum and ec- continues to be debated.

zema herpeticum), herpetic keratitis, and a severe Although HHV-6 was initially isolated in 1986

form of nonseasonal, focal encephalitis. HSV-2 is from the B lymphocytes of immunocompromised

the predominant cause of genital herpes, herpes adults, within two years it was described as the

proctitis, and neonatal herpes infections. cause of most cases of roseola (sixth disease). The

The most common manifestation of EBV infec- classic clinical picture of roseola, dating back to

tion is infectious mononucleosis, although EBV has 1910, is three to five days of high fever in an infant,

also been proposed as a cause of myriad diseases in- followed by the acute onset of a rose-pink, nonpru-

volving virtually every organ in the body. The mani- ritic, macular rash, predominantly on the neck and

festations of CMV infection overlap substantially trunk. Because of the abrupt onset of the rash, the

with those of EBV infection, and both viruses are disease was called exanthema subitum (“subitum”

important causes of prolonged febrile illnesses in meaning “sudden” in Latin).

normal hosts. VZV causes chickenpox and, with re- Subsequent reports identified HHV-6 as a major

activation, herpes zoster. cause of illness in young children who were brought

The pathogenic role of herpesviruses in some to emergency departments for the evaluation of fe-

754 n engl j med 352;8 www.nejm.org february 24, 2005

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH - MAIN on August 12, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

PERSPECTIVE Sixth Disease and the Ubiquity of Human Herpesviruses

have HHV-6 infection, more than 10 percent have

EBV HSV- 1 febrile seizures, and more than 10 percent are hos-

pitalized. HHV-6 appears to account for approxi-

mately one third of febrile seizures in children in

this age group.

The lack of a prospective, population-based study

of HHV-6 beyond the acute care setting had limited

our understanding of the full spectrum of illness

that is attributable to this virus. Zerr et al. have ad-

HSV- 2 VZV dressed this shortcoming. Using an intensive study

design that included the collection of weekly sam-

ples of saliva for the diagnosis of HHV-6 infection

on the basis of quantitative DNA testing, the Seattle

investigators prospectively followed a cohort of 277

infants from birth through two years of age. The fre-

quency and types of clinical illness associated with

HHV- 6 CMV HHV-6 infection were determined on the basis of

daily illness logs, and symptoms were compared

with those in age-matched controls who were not

acutely infected with HHV-6.

More than three quarters of the infants were in-

fected with HHV-6 by the second year of life, and

more than 90 percent of the infections were associ-

ated with symptoms. Fever and fussiness were the

most common manifestations of infection; roseola

Clinical Characteristics of Herpesviruses.

was diagnosed in about one quarter of the study

The image of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection shows a child with exudative

pharyngitis associated with infectious mononucleosis, the image of herpes

population. Almost 40 percent of the children were

simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection shows a paronychial infection (herpetic evaluated by a physician for symptoms coincident

whitlow), the image of herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection shows with their HHV-6 infection. In contrast to studies

ulcerative lesions on the vulva (genital herpes), the image of varicella–zoster involving febrile young children recruited from

virus (VZV) infection shows vesicular lesions in a dermatomal distribution emergency departments, this study showed that

(herpes zoster), the image of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) infection shows

a child with the rash of roseola, and the image of cytomegalovirus (CMV) in-

seizures were not a feature of HHV-6 infection.

fection shows chorioretinitis consistent with infection in an immunocompro- Remarkably, HHV-6 DNA remained detectable

mised host. EBV courtesy of Stanley Martin, M.D. at moderately high levels in saliva for at least 12

months after the initial infection. Although the pre-

cise relationship between the quantity of viral DNA

ver. Depending on the specific age range of the and transmissible virus has not been established,

population studied, 10 to 50 percent of febrile ill- previous studies have indicated that saliva is the

nesses leading to an emergency room visit have principal source of infectious virus. Previous studies

been attributed to HHV-6 infection, the peak age of also have demonstrated that persons who are sero-

infection being six to nine months. The conse- positive for EBV, CMV, HSV-1, and HSV-2 shed reac-

quences of HHV-6 infection diagnosed in children tivated virus frequently throughout their lives. Taken

in emergency departments may be substantial; together, these studies underscore an inescapable

among those younger than two years of age who epidemiologic fact: herpesviruses are ubiquitous.

n engl j med 352;8 www.nejm.org february 24, 2005 755

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org at UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH - MAIN on August 12, 2015. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cerebral Concussion - PresentationDocument19 pagesCerebral Concussion - PresentationAira AlaroNo ratings yet

- Buteyko Meets DR MewDocument176 pagesButeyko Meets DR MewAnonymous hndaj8zCA100% (1)

- Institutul de Boli CardioVasculare Prof DR George IM GeorgescuDocument9 pagesInstitutul de Boli CardioVasculare Prof DR George IM GeorgescuElena TraciNo ratings yet

- Spitalul Clinic DR C I ParhonDocument36 pagesSpitalul Clinic DR C I ParhonElena TraciNo ratings yet

- Institutul de Boli CardioVasculare Prof DR George IM GeorgescuDocument9 pagesInstitutul de Boli CardioVasculare Prof DR George IM GeorgescuElena TraciNo ratings yet

- Spitalul Clinic de Pneumoftiziologie IasiDocument8 pagesSpitalul Clinic de Pneumoftiziologie IasiElena TraciNo ratings yet

- Institutul Clinic de Psihiatrie Socola IasiDocument22 pagesInstitutul Clinic de Psihiatrie Socola IasiElena TraciNo ratings yet

- Spitalul Clinic de Obstetrica Ginecologie Elena Doamna IasiDocument5 pagesSpitalul Clinic de Obstetrica Ginecologie Elena Doamna IasiElena TraciNo ratings yet

- CV April Geo Savulescu WordDocument9 pagesCV April Geo Savulescu Wordmiagheorghe25No ratings yet

- Jdvar 08 00237Document3 pagesJdvar 08 00237Shane CapstickNo ratings yet

- SickLeaveCertificate With and Without Diagnosis 20240227 144109Document2 pagesSickLeaveCertificate With and Without Diagnosis 20240227 144109Sawad SawaNo ratings yet

- How to Keep Your Heart HealthyDocument11 pagesHow to Keep Your Heart HealthyLarissa RevillaNo ratings yet

- Challenges Providing Palliative Care Cancer Patients PalestineDocument35 pagesChallenges Providing Palliative Care Cancer Patients PalestineHammoda Abu-odah100% (1)

- Cesarean Delivery and Peripartum HysterectomyDocument26 pagesCesarean Delivery and Peripartum HysterectomyPavan chowdaryNo ratings yet

- NEET UG Biology Human Health and DiseasesDocument18 pagesNEET UG Biology Human Health and DiseasesMansoor MalikNo ratings yet

- Olivia Millsop - Case Study Docx 1202Document11 pagesOlivia Millsop - Case Study Docx 1202api-345759649No ratings yet

- Amazing Health Benefits of Coconut by The Coconut Research CenterDocument6 pagesAmazing Health Benefits of Coconut by The Coconut Research CenterEuwan Tyrone PriasNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Medicine Certification Examination Blueprint - ABIMDocument7 pagesGeriatric Medicine Certification Examination Blueprint - ABIMabimorgNo ratings yet

- Dept. of Pulmonology expertise in lung careDocument7 pagesDept. of Pulmonology expertise in lung carerohit6varma-4No ratings yet

- Objective Structured Clinical Examination (Osce) : Examinee'S Perception at Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Jimma UniversityDocument6 pagesObjective Structured Clinical Examination (Osce) : Examinee'S Perception at Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Jimma UniversityNuurNo ratings yet

- D-dimer and platelet aggregation predict thrombotic risk in PADDocument8 pagesD-dimer and platelet aggregation predict thrombotic risk in PADlidawatiNo ratings yet

- NCA - CVA InfarctDocument126 pagesNCA - CVA InfarctRosaree Mae PantojaNo ratings yet

- Living With CancerDocument400 pagesLiving With CancerAnonymous FGqnrDuMNo ratings yet

- Chapter 38 - Pediatric and Geriatric HematologyDocument3 pagesChapter 38 - Pediatric and Geriatric HematologyNathaniel Sim100% (2)

- Major & Mild NCD Terminology UpdatesDocument30 pagesMajor & Mild NCD Terminology Updatesrachelle anne merallesNo ratings yet

- Taking Medical HistoryDocument2 pagesTaking Medical HistoryDiana KulsumNo ratings yet

- Led Astray: Clinical Problem-SolvingDocument6 pagesLed Astray: Clinical Problem-SolvingmeganNo ratings yet

- How To Protect Yourself and OthersDocument2 pagesHow To Protect Yourself and OtherslistmyclinicNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site InfectionDocument7 pagesSurgical Site InfectionCaxton ThumbiNo ratings yet

- Micro K (Potassium Chloride)Document2 pagesMicro K (Potassium Chloride)ENo ratings yet

- Nursing Documentation for Wina Purnamasari's Immunization and Vital Signs CheckDocument6 pagesNursing Documentation for Wina Purnamasari's Immunization and Vital Signs Checkilah keciNo ratings yet

- National Mental Health ProgrammeDocument9 pagesNational Mental Health ProgrammeSharika sasi0% (1)

- Ob Assessment FinalDocument10 pagesOb Assessment Finalapi-204875536No ratings yet

- What Is ScabiesDocument7 pagesWhat Is ScabiesKenNo ratings yet

- Repositioning an Inverted UterusDocument5 pagesRepositioning an Inverted Uterusshraddha vermaNo ratings yet

- Ijmrhs Vol 2 Issue 1Document110 pagesIjmrhs Vol 2 Issue 1editorijmrhs100% (1)