Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Defining Emotions Socially and Culturally

Uploaded by

Kony Cabello SepulvedaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Defining Emotions Socially and Culturally

Uploaded by

Kony Cabello SepulvedaCopyright:

Available Formats

24 Ute Frevert Defining Emotions 25

..

over lower (physical) and higher (mental) emotions that was not setcled even in the gffiinated by a moralphil.osophy that had a high regard for social emotions. There

twencieth cencmy. In the l 950s and 1960s1 encyclopedias still distinguished becween a unanimous belief that society funccioned only if its members fostered public

emotions that were 'more' or 'less' physical in a dearly evaluative manner. The -ectíom, treating each other with sympachy, friendliness, and benevolence. Grati

former were supposed to be emocions 'that were primarily reactive, siruationally and údC, concern for reputation, and love of country were also important, as were

contextually determined'; che larter, by contrast, induding emotions that were 'soul ·,:-_?nescy, loyalty, and trust. There was a conviction that such feelings flourished to

,, _

ful and mental', 'aesthetic and ethical', were inherencly 'highly complex, stronger 'iji�_ir grearest extent in states whose governments respected the freedom and equal

and more habitual'. They hence marked the character and 'basic life mood' of a ify:of their citizens. If they were able to send representatives to parliament, their

person much more strongly and decisively as merely reactive emotions, or, to use feélings and intereses found representation. Such a representative constitution not

,

the concepts of Max Scheler and Hubert Rohrbacher, emotions chat are dos; to \ily ensured that cítizens could enjoy che fullest advancement of privare and social

sensations and drives (such as pain or fear).69 )notions, bue also attracted their love and their deference. Alongside civilizing

On the whole, however, differentiation of this kind retreated in che second half " iogress, it chus embodied social harmony and stability.7°

of che twentieth century, as reference works sought decidedly to absrain from value iÜn che ocher side of che English Channel, such chings could only be dreamt of.

judgements and prescriptions for moral behaviour. Enrries became more objective, ,' ivic activism in the service of che common good was not widespread in the Ger

concise and scientistic, in an effort to orienc themselves as closely as possible to the ., <an territorial states, and was not encouraged by absolucist authorities. lt was for

newly authoritative sciences (psychology and che neurosciences). At the same rime ;ic reason that che question of che origin and development of emotions that pre

they became detached from che variety of real life, since che phenomena to which 'Cupied Scottish moral philosophers found litde resonance in Germany. Instead,

they referred were removed from che social conrexts, isolared and universalized, S"��re che focus was upon the limited circles of bourgeois sociability: che family,

mimicking r.he practice of the experimental sciences. lnstead of dealing with 'peo ''rivate friendship, and, above ali, che development of emotion in individual men

ple' and their shifting feelings, sensations, and passions, as was che practice of {and women.

1

encyclopedias from the eighteenth to che early twentieth centuries, today che focus : ,,,,, Much time and effort were devoted to argufo.g about che readability of genuine'

,

is on 'the person', his or her brain, body, consciousness, and emotion(s). "'atld che pretep.ce of 'false' emotions. This reflected a need in bourgeois circles to

''áeate space for sociability in which people could set aside their social masks and

with each other politely, bue also candidly. Emotions here played a central

6. CONTEXTS OF EMOTION: NATIONS, SOCIAL for, as che Encycl.opedia Britannica emphasized in 1797, they represented a

language' and promoted social communication. 'Society among indi

CLASSES, GENDER

is greacly prometed by that universal language. Looks and ges c ures give

Recenc reference works have chereby more or less given up seeking to provide any access to che heart; and lead us ro select, with tolerable accuracy, che persons

normative orientation that might lend cheir readers a salid self-consciousness and are wonhy of our confidence.' Even when people sought to hide their emo

iniciare chem into a particular way of conducting rheir lives. Not least, chis is related 'nature' was thought to set strict limits to such deception through visual

to a growing heterogeneity of readers and users who resise reduction to chis or that

way of thinking, unlike che relatively manageable bourgeois readership of che eighc Germany, where authoritarian structures set greater limits on che freedom of

eenth and nineceenth centuries. At che same time, much of che context conveyed in sociability, there was a greater element of doubt. Were there really unambigu

earlier encyclopedias is left out here, omitting precísely che material that makes it proofs of che authenticity and candidness of emotions? Were word, gesture,

possible for today's historians to gain access to che emotions ofearlier generacions. facial expression to be trusted? (There are people', one popular newspaper

Pare of this contextual knowledge was that emotions, however natural they in 1803, 'who never miss an opportunity to unleash sensitive tirades, even

might be, were to a great extent formed culturally and socially. Who felt what, and into tears', bue who are nonetheless 'hard-hearted' and selfish. Words were

how rhey expressed it, depended upon che given circumstances of cheir lives, cheir enough to satisfy che contemporary demand for 'deep emotion, even enthusi

level ofeducation, and their age and gender, bue ic also depended u pon che general asm'. 'A facial expression, a glance, even che way that they listen, how they observe,

development of a society and its leve! of political maturity. These last two fu.ctors in says much, much more than can the most eloquent speech-but only to those who

particular played an important pare in encyclopedia entries. , , themselves possess emotion. '72

Incerest in che framework that a society gave to emotions was especially strong

70 'Moral philosophy' in EB, lst edn, iii (1771), 270-309, largely unchanged in the 7th edn, xv

in Great Britain. From the eighteenth century up to che 1840s, discussion was

(1842), 456-89.

71

'Passion' in EB, 3rd edn, xiv (1797), 7-8.

6 72 'Mancherlei Gedanken über die Kunst zu gefullen', Ernst:md Scherz, 27 (1 October 1803), 107.

� 'Gefühl', in Brockham, 16th edn, iv (1954), 435-6; 'Gefühl, Emotion', in Brockhaus, 17th edn,

vii (1969), 1.7. This article is cited in 'Trieb', in Krünitz, clxxxv {1846), 7.

You might also like

- Inexpressible Privacy: The Interior Life of Antebellum American LiteratureFrom EverandInexpressible Privacy: The Interior Life of Antebellum American LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Faces of Communities: Social Ties between Trust, Loyalty and ConflictFrom EverandFaces of Communities: Social Ties between Trust, Loyalty and ConflictSabrina FeickertNo ratings yet

- Isaiah Berlin OriginsDocument28 pagesIsaiah Berlin OriginsNely FeitozaNo ratings yet

- Hultquist (2017) - Introductory Essay Emotion, Affect, and The EighteenthDocument9 pagesHultquist (2017) - Introductory Essay Emotion, Affect, and The EighteenthEnson CcantoNo ratings yet

- Los Usos de La LiteraturaDocument7 pagesLos Usos de La LiteraturaDavid LuqueNo ratings yet

- Matt, S.J. Recovering The InvisibleDocument14 pagesMatt, S.J. Recovering The InvisibleJulia BacchiegaNo ratings yet

- Barclay, K. - 2021 - State of The Field - The History of EmotionsDocument11 pagesBarclay, K. - 2021 - State of The Field - The History of EmotionsGinno MartinezNo ratings yet

- Feeling Sentiment EyesDocument22 pagesFeeling Sentiment EyesAnna DybiecNo ratings yet

- History of Cultural Perceptions and FeelingsDocument25 pagesHistory of Cultural Perceptions and Feelingsserenity_802No ratings yet

- VerstehenDocument11 pagesVerstehenapi-298063936No ratings yet

- The Erotics of Mourning in Recent Experimental Black PoetryDocument16 pagesThe Erotics of Mourning in Recent Experimental Black Poetryajohnny1No ratings yet

- Paradigm for the Sociology of KnowledgeDocument8 pagesParadigm for the Sociology of KnowledgeCAREL FAITH M. ANDRESNo ratings yet

- The Rediscovery of Community in 19th Century ThoughtDocument5 pagesThe Rediscovery of Community in 19th Century ThoughtRadu IlcuNo ratings yet

- Classen Constance - Sweet ColorsDocument15 pagesClassen Constance - Sweet ColorsYeshica S. Ochoa LozanoNo ratings yet

- The Folk Society: Understanding Primitive Culture Through an Ideal TypeDocument16 pagesThe Folk Society: Understanding Primitive Culture Through an Ideal Typecorell90No ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence in the Poetry of Plath, Sexton and RichDocument274 pagesEmotional Intelligence in the Poetry of Plath, Sexton and RichtkesNo ratings yet

- Schmitt - The Rationale of GesturesDocument12 pagesSchmitt - The Rationale of GesturesMarilisa DiminoNo ratings yet

- Social Opacity and The Dynamics of Empat - Dream Self Preguntar A FernandoDocument22 pagesSocial Opacity and The Dynamics of Empat - Dream Self Preguntar A FernandounsietequetecreesNo ratings yet

- Social: TheoryDocument44 pagesSocial: Theorysasori89No ratings yet

- Portrait of A Young Painter by Mary Kay VaughanDocument35 pagesPortrait of A Young Painter by Mary Kay VaughanDuke University PressNo ratings yet

- Mapping Emotions Constructing FeelingsDocument34 pagesMapping Emotions Constructing Feelingsgiulia grassiNo ratings yet

- Media and ReDocument13 pagesMedia and ReVictor Baldesco JrNo ratings yet

- Reader in Contemporary Critical Theories. Bucharest: The English Department of The University ofDocument7 pagesReader in Contemporary Critical Theories. Bucharest: The English Department of The University ofAlexandra MihaiNo ratings yet

- Keesing Roger Anthropology As Interpretive QuestDocument17 pagesKeesing Roger Anthropology As Interpretive QuestSotiris LontosNo ratings yet

- The Reformation of Feeling - Susan C. Karant-NunnDocument353 pagesThe Reformation of Feeling - Susan C. Karant-Nunnsbr100% (1)

- SM 1cultureDocument128 pagesSM 1cultureshivam mishraNo ratings yet

- Foundations for an anthropology of the sensesDocument12 pagesFoundations for an anthropology of the sensesRuby July Peñaranda EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Foundations For An Anthropology of The SensesDocument12 pagesFoundations For An Anthropology of The SensesAlex Carlill100% (2)

- Revestudsoc 939Document7 pagesRevestudsoc 939Marta MegaNo ratings yet

- Assmann Communicative and Cultural Memory 2008Document10 pagesAssmann Communicative and Cultural Memory 2008Lizabel MónicaNo ratings yet

- The Ethnographers Magic As Sympathetic M PDFDocument15 pagesThe Ethnographers Magic As Sympathetic M PDFPedro FortesNo ratings yet

- The Social Imaginary Unveiled in Quechua Myths and SongsDocument19 pagesThe Social Imaginary Unveiled in Quechua Myths and Songscamille100% (1)

- Emotions in The Household: Susan BroomhallDocument2 pagesEmotions in The Household: Susan BroomhallAniket KulkarniNo ratings yet

- GEERTZ 1983, Centers, Kings, and Charisma Reflections On The Symbolics of PowerDocument14 pagesGEERTZ 1983, Centers, Kings, and Charisma Reflections On The Symbolics of PowerFrancesco Maria FerraraNo ratings yet

- To Find/Make Meaning: Notes On The Last Permission: by James R. Allen and Barbara Ann AllenDocument10 pagesTo Find/Make Meaning: Notes On The Last Permission: by James R. Allen and Barbara Ann AllenВасилий МанзарNo ratings yet

- Fragile Minds and Vulnerable Souls: The Matter of Obscenity in Nineteenth-Century GermanyFrom EverandFragile Minds and Vulnerable Souls: The Matter of Obscenity in Nineteenth-Century GermanyNo ratings yet

- Sennett - Richard Authority W. W. Norton - Company - 1993Document175 pagesSennett - Richard Authority W. W. Norton - Company - 1993Pedro RafaelNo ratings yet

- The Emotions in Early Chinese PhilosophyDocument241 pagesThe Emotions in Early Chinese PhilosophyPaco Ladera100% (3)

- Chapter-II Folklore, Text and The Performance Approach: Folklore As A DisciplineDocument25 pagesChapter-II Folklore, Text and The Performance Approach: Folklore As A DisciplineFolklore y LiteraturaNo ratings yet

- NOTES in ART APPRECIATION No 1ADocument6 pagesNOTES in ART APPRECIATION No 1ADUMLAO, ALPHA CYROSE M.0% (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 157.253.50.50 On Sat, 30 Jan 2021 22:11:41 UTCDocument21 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 157.253.50.50 On Sat, 30 Jan 2021 22:11:41 UTCCarlos Mauricio VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Definisi BudayaDocument4 pagesDefinisi BudayaHada fadillahNo ratings yet

- Acsa Am 94 44Document12 pagesAcsa Am 94 44MariaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 History and AnthropologyDocument9 pagesLecture 9 History and AnthropologyDaniel MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 History and AnthropologyDocument9 pagesLecture 9 History and AnthropologyDaniel MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Sacks EDAH Journal Dignity of DifferenceDocument15 pagesJonathan Sacks EDAH Journal Dignity of DifferencedavidshashaNo ratings yet

- Hall Culture, Comunity, NationDocument8 pagesHall Culture, Comunity, NationHerrSergio SergioNo ratings yet

- Anthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryFrom EverandAnthropology Through a Double Lens: Public and Personal Worlds in Human TheoryNo ratings yet

- EhessDocument13 pagesEhessWendel de HolandaNo ratings yet

- Alexander Et Al. - Risking Enchantment-Theory & Method in Cultural StudiesDocument5 pagesAlexander Et Al. - Risking Enchantment-Theory & Method in Cultural StudiesmargitajemrtvaNo ratings yet

- History of Emotions Review EssayDocument11 pagesHistory of Emotions Review EssayamparoNo ratings yet

- Mass Society Daniel BellDocument8 pagesMass Society Daniel Bellnikiniki9No ratings yet

- What Culture? : M. FosterDocument15 pagesWhat Culture? : M. FostermainaoNo ratings yet

- ILJ 6.1 ErmineDocument11 pagesILJ 6.1 Ermineeli_s173No ratings yet

- Carvallo - Latin America - A Region SplitedDocument11 pagesCarvallo - Latin America - A Region SplitedAlejandro Carvallo MachadoNo ratings yet

- Shalin1996 - Soviet Civilization and Its EmotionalDocument32 pagesShalin1996 - Soviet Civilization and Its EmotionalAhmad AhmadNo ratings yet

- Scent Sound and SynaesthesiaDocument12 pagesScent Sound and SynaesthesiaJiaying SimNo ratings yet

- Dystopian Community in Lois Lowry's Novel The Giver 2Document2 pagesDystopian Community in Lois Lowry's Novel The Giver 2Monica TomaNo ratings yet

- Mapping The Cosmic PsycheDocument18 pagesMapping The Cosmic Psychepaul_advaitaNo ratings yet

- 15 Common Defense Mechanisms ExplainedDocument2 pages15 Common Defense Mechanisms ExplainedDonnah Vie MagtortolNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Child DevelopmentDocument17 pagesFactors Influencing Child DevelopmentMuhammad Zulfadhli0% (1)

- Analogy To Help Your Child Understand Their Big Emotions UKDocument3 pagesAnalogy To Help Your Child Understand Their Big Emotions UKKata KadekNo ratings yet

- Assertive CommunicationDocument20 pagesAssertive CommunicationJacob Mathew Pulikotil100% (1)

- Test Anxiety BookletDocument17 pagesTest Anxiety BookletStarLink1100% (1)

- Overcoming ShynessDocument2 pagesOvercoming ShynessAllan LegaspiNo ratings yet

- The Fight or Flight ResponseDocument22 pagesThe Fight or Flight ResponseKaushalNo ratings yet

- The Door of Everything by Ruby NelsonDocument35 pagesThe Door of Everything by Ruby NelsonNaren Dran100% (1)

- The Role of Acceptance and Job Control in Mental Health, Job Satisfaction, and Work PerformanceDocument12 pagesThe Role of Acceptance and Job Control in Mental Health, Job Satisfaction, and Work PerformanceSanto ZaqNo ratings yet

- SMK Simpang Rengam's Grand National Day CelebrationDocument8 pagesSMK Simpang Rengam's Grand National Day Celebrationjennifer_lim_21No ratings yet

- Mental Health DisordersDocument4 pagesMental Health DisordersJANEL BRIÑOSANo ratings yet

- Reading ComprehensionDocument19 pagesReading ComprehensionMd parvezsharifNo ratings yet

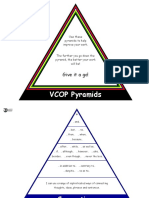

- VCOP Pyramids IndividualDocument5 pagesVCOP Pyramids IndividualmrbalintNo ratings yet

- Kizanlikliandener 2012Document8 pagesKizanlikliandener 2012Sumitha GNo ratings yet

- Causes and Effects ProposalDocument24 pagesCauses and Effects ProposalkasuNo ratings yet

- MGTDocument37 pagesMGTMajid khanNo ratings yet

- William G. Roll and Michael A. Persinger - Is ESP A Form of Perception?: Contributions From A Study of Sean HarribanceDocument11 pagesWilliam G. Roll and Michael A. Persinger - Is ESP A Form of Perception?: Contributions From A Study of Sean HarribanceAuLaitRSNo ratings yet

- Stuart Wilde God S GladiatorsDocument190 pagesStuart Wilde God S GladiatorsErEledth92% (12)

- Compare and Contrast AssignmentDocument4 pagesCompare and Contrast AssignmentRuzuiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Diagnosis 3Document2 pagesNursing Diagnosis 3Mark Cau Meran100% (2)

- CommunicationDocument40 pagesCommunicationLekshmi Manu100% (1)

- Assessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsDocument27 pagesAssessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsCitizenNo ratings yet

- Dogs' Guilty Looks: Understanding Canine EmotionsDocument4 pagesDogs' Guilty Looks: Understanding Canine EmotionsJack CastilloNo ratings yet

- JFSC E102Document3 pagesJFSC E102osto72No ratings yet

- Unit 1.1Document40 pagesUnit 1.1Sunil RupjeeNo ratings yet

- Build resilience with 10 coping techniquesDocument7 pagesBuild resilience with 10 coping techniquesLaura PârvulescuNo ratings yet

- Basics of The Cognitive ApproachDocument2 pagesBasics of The Cognitive Approachajhh1234No ratings yet

- Stress Theory: Ralf SchwarzerDocument24 pagesStress Theory: Ralf SchwarzerAlera KimNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Mood Tracking ChartDocument2 pagesBipolar Mood Tracking ChartMegan PenroseNo ratings yet

- Bput Mba 09 12 PTDocument71 pagesBput Mba 09 12 PTAakash LovableNo ratings yet