Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1152 Lab Manual Exp10

Uploaded by

Nitty MeYaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1152 Lab Manual Exp10

Uploaded by

Nitty MeYaCopyright:

Available Formats

49

Experiment 10- Calorimetry of Foods

Introduction Animals obtain the energy necessary for life from food. Food is oxidized to carbon dioxide and water with an associated release of energy. Fortunately for us, our cells convert much of this energy into useful work, instead of releasing all of it as heat. Using glucose as an example, nearly half of the energy content of glucose is converted to useful energy in our bodies. In contrast, a car engine converts less than 10% of the energy content of gasoline into mechanical energy and releases the rest as heat. Hess' Law tells us that in going from a specific reactant to a specific product, the same amount of energy will be released (or consumed) regardless of the pathway. Most of the carbon atoms in a peanut, for example, will be oxidized to carbon dioxide and water in our bodies- providing a certain number of calories of energy. The same amount of energy is released by burning the peanut to produce these same products. This heat can be used to heat a known mass of water. The temperature change of the water can be used to calculate the amount of energy added to the water. Since the energy added to the water came from the combustion of the peanut, we know how much energy was released from the peanut assuming all of the energy was transferred. Different types of foods have different energy contents. Glucose has approximately 4 Calories of energy per gram. Fat (triglycerides) on the other hand have about 9 Calories per gram. Ethanol has 7 Calories of energy per gram. A nutritional Calorie (listed on food labels) is 1 kcal or 1000 calories. Foods with a high fat content will be most effective in this experiment. Apparatus Suspend a 12 oz. soda can on a ring stand as shown below.

50 Laboratory Activities A. B. Use calorimetry to determine the energy content of a peanut Determine the energy content of a second food item.

Preparation Peanuts will be available for use in the lab. Each group should bring an appropriate second item to test. Other nuts (e.g. cashews) work well as do cheese puffs, cheese wafers, and various (greasy) chips. Procedure 1. Weigh the modified soft drink can. Pour about 50 mL of water into the soft drink can. Reweigh the can and record the mass of water as accurately as possible. 2. Suspend the can as shown previously in the diagram. 3. Accurately measure the temperature of the water. 4. Weigh a peanut and place it on the end of a needle or hold it using forceps. Set fire to the peanut. 5. Quickly place the peanut under the can and use the flame to heat the can. Stir the water as the sample burns. Reignite if necessary. 6. After the peanut has burned as much as possible (without excessive delay in which the water might cool down), record the temperature of the water. 7. Repeat the procedure using a different food. You may wish to try a small marshmallow, cheese curl, potato chip, or other food that you wish to bring in. Greasy junk food generally burns well. It is important for it to readily burn completely.

51

Experiment 10 Laboratory Record

Name:_______________________

Sample # 1: (be specific) __________________________________ 1. mass of water __________ grams 2. mass of sample __________ grams 3. temperature of H2O after burning __________ C 4. temperature of H2O before burning __________ C 5. change in temperature of the H2O __________ C 6. total energy content of sample: (show calculations below) __________ kcal 7. energy content per gram of sample __________ kcal/gram Calculations: heat (in cal)= (specific heat of water) x (mass of water) x (change in temperature) Note that: (specific heat of water= 1.00 cal/g C) (1 kcal = 1000 cal)

Sample # 2: (be specific) __________________________________ 1. mass of water __________ grams 2. mass of sample __________ grams 3. temperature of H2O after burning __________ C 4. temperature of H2O before burning __________ C 5. change in temperature of the H2O __________ C

52 6. total energy content of sample: (show calculations below) 7. energy content per gram of sample Calculations:

__________ kcal __________ kcal/gram

How does your experimental value for each of the samples compare to the energy value listed on the label?

If 100 mL of water is used in the can (instead of 50 mL), will the experiment still give accurate results? Explain.

If only a small portion of a peanut (say one-fourth of a nut) is used, will the experiment still give accurate results? Explain.

Other than mistakes, suggest at least 3 factors that affected the accuracy of your results.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Heat SettingDocument1 pageHeat SettingNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Your BibliographyDocument1 pageYour BibliographyNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Experiment Report: Spectrophotometric Analysis of Caffeine and Benzoic Acid in Soft DrinkDocument12 pagesExperiment Report: Spectrophotometric Analysis of Caffeine and Benzoic Acid in Soft DrinkNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Application FormDocument5 pagesApplication FormNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Experiment 4Document2 pagesExperiment 4Nitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Important Contact ParticularsDocument1 pageImportant Contact ParticularsNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Experiment 1Document3 pagesExperiment 1Nitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Solvolysis of Salt of A Weak Acid and Weak BaseDocument11 pagesSolvolysis of Salt of A Weak Acid and Weak BaseNitty MeYa100% (1)

- Appendix 1 IT Indemnity LetterDocument1 pageAppendix 1 IT Indemnity LetterNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- DSC PmmaDocument1 pageDSC PmmaNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- DyesDocument18 pagesDyesNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Components For Polyamides Products of PropeneDocument58 pagesComponents For Polyamides Products of PropeneNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Total Suspended & Dissolved SolidsDocument22 pagesTotal Suspended & Dissolved SolidsNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- ManualDocument5 pagesManualNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

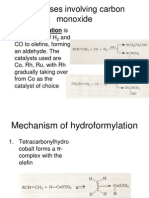

- Carbon Monoxide and EhtyleneDocument58 pagesCarbon Monoxide and EhtyleneNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Acetylene DienesDocument16 pagesAcetylene DienesNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Organic Qualitative Analysis Aldehydes and KetonesDocument4 pagesOrganic Qualitative Analysis Aldehydes and KetonesNitty MeYa50% (2)

- Thermo SolutionDocument9 pagesThermo SolutionNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Density ExperimentDocument9 pagesDensity ExperimentNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Density Determination by PycnometerDocument5 pagesDensity Determination by PycnometerAlexandre Argondizo100% (1)

- Density of A Liquid MixtureDocument7 pagesDensity of A Liquid MixtureNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 P-Block ElementsDocument18 pagesUnit 9 P-Block ElementsfesinNo ratings yet

- Alcohol, Aldehyde and KetonesDocument12 pagesAlcohol, Aldehyde and KetonesFranky TeeNo ratings yet

- Density of A Liquid MixtureDocument7 pagesDensity of A Liquid MixtureNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Chem 415 Experiment 1Document6 pagesChem 415 Experiment 1ttussenoNo ratings yet

- Group 17Document11 pagesGroup 17Nitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- DensityDocument5 pagesDensityNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Chromium ComplexesDocument3 pagesChromium ComplexesNitty MeYa100% (1)

- Gas Law ExperimentDocument3 pagesGas Law ExperimentNitty MeYaNo ratings yet

- Chromium ComplexesDocument3 pagesChromium ComplexesNitty MeYa100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- CV of Hannan Sarker. - Kishwan Snacks Limited - Manager - QCDocument4 pagesCV of Hannan Sarker. - Kishwan Snacks Limited - Manager - QCEmonNo ratings yet

- Qualitative and Quantitative Loss Assessment of Selected High Value Food Crops (Mango, Banana, Calamansi, Carrots, Cabbage, Onion)Document15 pagesQualitative and Quantitative Loss Assessment of Selected High Value Food Crops (Mango, Banana, Calamansi, Carrots, Cabbage, Onion)UPLB Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and ExtensionNo ratings yet

- The List What The Top Fitness Models Don T Want You To Know PDFDocument33 pagesThe List What The Top Fitness Models Don T Want You To Know PDFРафаэль Сэрба дэ Баланґэ100% (2)

- Café Jardin's Strategies for Growth & CompetitivenessDocument18 pagesCafé Jardin's Strategies for Growth & CompetitivenessUsman KhanNo ratings yet

- (The Oily Press Lipid Library) Frank Gunstone - Lipids For Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals-Woodhead Publishing (2003) PDFDocument341 pages(The Oily Press Lipid Library) Frank Gunstone - Lipids For Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals-Woodhead Publishing (2003) PDFCamilo Andrés CastroNo ratings yet

- What Is Hyperthyroidism?Document11 pagesWhat Is Hyperthyroidism?Sai PraneethNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Principles of Microeconomics 8th Edition Mankiw 1305971493 9781305971493Document36 pagesTest Bank For Principles of Microeconomics 8th Edition Mankiw 1305971493 9781305971493GeorgeObriendmwsq100% (16)

- Clean EatingDocument92 pagesClean EatingLia Vágvölgyi100% (1)

- Checklist of The Processing Area To Be InspectedDocument2 pagesChecklist of The Processing Area To Be InspectedBFAR 10 PHMS100% (1)

- Module-2 Notes - 22SFH18Document16 pagesModule-2 Notes - 22SFH18maheshanischithaNo ratings yet

- Filipino Cultural Interview PaperDocument13 pagesFilipino Cultural Interview Paperapi-285132682100% (2)

- Editorial board and preface of the 100 recipes Ayurvedic cookbookDocument53 pagesEditorial board and preface of the 100 recipes Ayurvedic cookbookLaura VillalobosNo ratings yet

- Values Education Syllabus.Document13 pagesValues Education Syllabus.Morris Centeno64% (11)

- Nutri Lab 10Document38 pagesNutri Lab 10Carl Josef C. GarciaNo ratings yet

- Potato Chips Manufacturing ProcessDocument126 pagesPotato Chips Manufacturing ProcessRichardNo ratings yet

- Pollution-Word 1Document2 pagesPollution-Word 1Alina Elena Cioaca100% (1)

- Course Syllabus and Content Front Office ServiceDocument11 pagesCourse Syllabus and Content Front Office ServiceKatherine BalbidoNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Food Packaging Materials Andres DavidDocument6 pagesCharacteristics of Food Packaging Materials Andres DavidStephania GonzalezNo ratings yet

- NaomiWhittel Ebook Glow15Kitchen PDFDocument28 pagesNaomiWhittel Ebook Glow15Kitchen PDFChandani100% (3)

- Design of Interior Fridge & FreezerDocument80 pagesDesign of Interior Fridge & FreezerNetsanet ShikurNo ratings yet

- HLPE Youth Engagement Employment Scope PROCEEDINGSDocument126 pagesHLPE Youth Engagement Employment Scope PROCEEDINGSMuhammad YaseenNo ratings yet

- Modern Technology of Food Processing & Agro Based Industries (2nd Edn.)Document8 pagesModern Technology of Food Processing & Agro Based Industries (2nd Edn.)Bala Ratnakar KoneruNo ratings yet

- Iso 22000 Implementation in The Animal Feed Industry For ImportDocument5 pagesIso 22000 Implementation in The Animal Feed Industry For ImportLee VsNo ratings yet

- Kellogg's Potential in Czech Cereal MarketDocument23 pagesKellogg's Potential in Czech Cereal MarketAmal HameedNo ratings yet

- UNIT 6 Reading ComprehensionDocument1 pageUNIT 6 Reading Comprehensionanabell vallejoNo ratings yet

- US Food System FactsheetDocument2 pagesUS Food System Factsheetmatthew_hoffman_19No ratings yet

- A Proposed Vertical Farm Strucutre in Bacolod CityDocument5 pagesA Proposed Vertical Farm Strucutre in Bacolod CityRod NajarroNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan NutritionDocument7 pagesLesson Plan NutritionMei Shan Siow100% (1)

- Handout Elimination Diet PatientDocument6 pagesHandout Elimination Diet PatientKateOpulenciaNo ratings yet

- Business plan for salty snack factoryDocument25 pagesBusiness plan for salty snack factoryricha_mfc100% (1)