Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 4 Stopford

Uploaded by

andiekalton869042Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 4 Stopford

Uploaded by

andiekalton869042Copyright:

Available Formats

STOPFORD Chapter 4 demand and supply General: How can a shipping investor deal with the high volatility

ty that characterizes all shipping markets? The usual advice is to buy low and sell high. An investor may correctly predict an upcoming freight market but when the same is achieved by a charterer there will not be any long term contracts. Similarly, in a weak market some investors may be willing to buy cheap ships but who is going to sell them for a loss? In general, the best opportunities appear to those who can judge correctly when the other players are wrong. Key influences on supply and demand: Stopford in an attempt to explain the mechanisms which determine freight rates developed a simple model incorporating the influences that demand and supply of transport receive. The model has three components; demand, supply and the freight market which links the two by regulating the cashflow from one sector to another. The way the model works is very simple. On the demand side, the world economy through the activity of the various industries generates the goods that require transport. Developments in a particular industry sectors such as a change in the price of oil may modify the general growth trend as may changes in the distance over which the cargo is transported giving a final demand for shipping services measured in ton miles. Ton miles is a technically more correct means of measuring demand than the deadweight of ships since it avoids making a judgement about the efficiency with which ships are used. On the supply side, the merchant fleet represents the shipping capacity. At a point of time some ships may only trade since some are laid up or used for storage. The fleet can be expanded by new shipbuildings and reduced by scrapping. The amount of transport that this fleet provides also depends on the efficiency with which ships are operated/finally, the policies of shippers, bankers, banks and regulators all have an impact on the supply side of the market. Then comes the market cycle scenario. It should be noted that mathematical models can never be totally reliable since the model of the shipping market incorporates the behavioral element, which is it depends on the way shipping investors respond to changes. Demand is volatile, quick to change and unpredictable. Supply is ponderous and slow to change. Supply always seeks to reach demand and a balance is the objective and it is ultimately rarely achieved. DEMAND FOR SHIPPING TRANSPORT: 1. The world economy: that there should be a close correlation between the world economy and demand for sea trade should be expected since the world economy generates most of the demand for sea transport through either the import of raw materials for manufacturers or the trade in manufactured goods. There are three different aspects of world economy that can change the demand for sea transport and these include the business cycles, the trade elasticity and trade development cycle: Business cycles: they lay the foundation for freight cycles and their causes are: i. The multiplier and the accelerator: income may be spent on commodity and investment goods. When investment increases, more labor is used; this additional labor spends its wage and an additional demand is generated driving further investment. At one time, capital and labour is utilized at the maximum degree and consequently the sequence is repeated into reverse. As a result, instability is generated in the economic machine.

Time-lags. The delays between economic decisions and their implementation can make fluctuations more extreme. For example, in a shipping market boom, shipowners order new ships which are not delivered until a recession has arrived; this additional capacity further squeezes freight rates. As a result of these time-lags, booms and recessions are more extreme and cyclical. iii. Stockbuilding: during recessions, manufacturers turn to utilize their stocks further intensifying the low demand for sea transport; on the other hand, in an upcoming market, the necessity to rebuild their stocks result in a sudden burst for sea transport. iv. Mass psychology: when individuals act independently, their errors are cancelled out but when they act in an imitative manner, they can affect the whole economic system. v. Random shocks: they include weather changes, wars, new resources, commodity price changes. An example can be the change of the oil price in 1973 which caused a shock in the oil market. vi. In conclusion, it has to be noted that in the shipping industry market cycles are evident. The periodicity, i.e. the distance from peak to peak and their magnitude is variable. The position of the peak and the trough of a cycle in progress is not predictable. Business cycles represent a short-term influence in the seaborne trade demand. Trade elasticity: it is the long-term influential factor of the demand for seaborne trade. It is the percentage of growth of sea trade divided by the percentage growth of industrial production. While since early 1970s the trade elasticity was between 1.6 and 1.4, in the 1990s it became highly volatile. That was because of the slowness of the economic development of the OECD countries and the exponential development of the Asian economies. There are three reasons why the trade elasticity of individual regions will change. Initially, own resources may be depleted or commodities of better quality are required and/or it is available trough cheap transport costs. As examples, coal resources in Europe were depleted and coal extraction became uneconomical, imports took place. Another reason is that when some economies mature, there is a shift in the focus of these economies from manufactured commodities to durables such as medical care, education etc. Finally, new countries may emerge as strong industrial entities changing in this way the distribution of industrial consumption. ii. 2. Seaborne commodity trades: many commodities trades are influenced by seasonality. For example agricultural products such as grain, sugar, and citrus fruit are subject to seasonal variations depending on the harvest level. In case of oil, more quantities are shipped during the autumn and early winter in the European region due to climate conditions. Although every business is different, there are four types of changes: i. Changes in demand for that particular commodity: an example is the oil the demand for which during the 1960s grew at 2-3 times as fast as the general rate of economic growth but the situation was reversed during the 1970s when the demand for crude oil stagnated. ii. Changes in supply sources: again in the case of oil, while in the 1960s the main source was the Middle East, new oil exploitation in Alaska and the North Sea changed supply sources. iii. Relocation of processing plant: for example 3 tons of bauxite are needed to produce 1 ton of alumina and 2 tons of alumina are needed to produce 1 ton of aluminium; as a result if the plant decides to process bauxite and finally ship alumina, then there is a change in the demand pattern. 2

iv. Changes in the shippers transport policy: for example, until the 1970s the oil majors controlled the oil transport by owning ships while chartering a small proportion to cover seasonal and any particular needs. After the crisis of 1973, they completely changed their policy and withdraw from the ship and transport management segment depending at a higher degree on the spot market. 3. Average haul and ton miles: the demand for sea transport depends upon the distance over which the cargo is transported. For example a ton of oil shipped from Middle East to Rotterdam via the Cape generated 2-3 times as much demand as the same quantity shipped from Libya to Marseilles. This distance effect is called the average haul and it is equal to the tonnage of cargo shipped multiplied by the average distance over which it is transported. It is a means to measure sea transport demand and technically is better since ship productivity is not considered. The changing demand due to distance changes has been illustrated in the past by the closure of the Suez Canal and the increase by 5000 miles from the Arabian Sea to Europe via the cape. 4. Political disturbances: it is impossible to exclude politics from the demand for seaborne trade. The significant features of the political disturbances is that when they occur their generate a sudden and unexpected demand changes. Political event is used to refer to such occurrences such as war, revolution or even strikes. It is the consequences of these events that influence demand rather the events themselves. Another significant characteristic is the shipping economist dealing with market forecast are usually inexperienced in the politics area and since forecasting entails great deal of information, loopholes appear. Examples of such political disturbances include the Korean War, the Suez crisis, the 6-day war between Israel and Egypt and the Gulf war. 5. Transport costs: raw materials will be transported from distant sources if the cost of the shipping operation can be reduced to an acceptable level or some major benefits are obtained in the quality of the product. As a result, transport cost plays a significant role in the seaborne trade demand. Over the last century, bigger ships have come into trade, efficient organization of the shipping operations, a steady reduction of the transport costs and a higher quality of service have been achieved. In fact, the cost of transporting a ton of coal from the Atlantic to the pacific has hardly changed. Transport costs have a strong longterm effect on the demand for transport services. THE SUPPLY OF SEA TRANSPORT The supply of ships is controlled by four groups of decision makers: the shipowners, the charterers/shippers, the bankers who finance shipping and various regulatory authorities who make rules for safety. Shipowners are the primary players; they are the ones who order new ships, scrap the old ones and decide when to lay up tonnage. Shippers may become owners themselves or influence shipowners through time charters. Bank lending influences investments and they often apply pressure in weak markets leading to higher scrapping activity. In respect to the regulators, consider regulation 13G of MARPOL. Prior to discussing about the influences of the supply part, it should be noted that the relationships in the shipping model are behavioral. 1. The merchant fleet: the capacity of the global merchant fleet is regulated on the long run by the scrapping and deliveries. The global fleet consists of a range of different types of vessels. Initially, we have the oil tanker fleet, the 3

combined carrier fleet, the dry bulk carrier fleet and the deep sea liner fleet consisting mainly of cellular container vessels and in a smaller proportion by reefers and ro-ros. a striking characteristic of the global fleet has been the increasing size of ships. In respect to the tanker fleet, their size reached its ceiling in the early 1980s; bulk carriers have reached the so-called Cape size while containers of even 16,000 TEU capacity are ready to be built by Samsung shipyards. At the same time, great specialization has occurred with chemical tankers, LPGs and LNGs trading. 2. Fleet Productivity: carriage of cargo by merchant ships is only a part of what merchant ships actually do. In general, one third of a ships life is spent on freight transport whereas the rest time is spent on non-trading activities such as ballast voyages, accidents, repairs, maintenance, dry-docking etc. such activities are determined not only by the physical performance of the fleet but also by market forces. The productivity of a fleet of ships measured in ton miles per dwt depends by four factors: i. Speed: ships in general operate at average speeds well below their design speed and this change with time. If ships delivered have a lower design speed, then voyages performed will be less; the supply s influenced. ii. Port time: the time spent by a ship at port is very important in the determination of the time of the whole voyage; in recent times, much focus has been given on the improvement of cargo handling at ports. Containerization emerged and within a JIT environment ship turnaround time has been greatly reduced. In addition, congestion can also generate supply problems. iii. DWT utilization: it refers to the cargo capacity lost owing to bunkers, stores and other reasons that prevent full load capacity. Surveys indicate that capacity utilization for bulk carriers and tankers is 95 and 96% respectively. iv. Loaded days at sea: this factor is correlated to the already mentioned; a reduction in the number of the unproductive days (ballast, dry-docks etc) equals an increase in the loaded days and consequently the productivity of the fleet increases. Vessels designed for maximum flexibility can switch between trades as for example in the case of OBOs. 3. Shipbuilding. 4. Demolition activity. 5. Freight rates: this is the ultimate regulator which the market uses to motivate decision makers to adjust capacity in the short term and to find ways or reducing costs in the long term. The way the fright market operates is simple enough. Shipowners and shippers negotiate to establish a freight rate which reflects the balance of ships and cargoes available in the market. If there are many ships, the freight rate is low while if there are few ships the freight rate will be higher. Once this freight rate is established, shipper and shipowners adjust to it and eventually this brings demand and supply into balance. Three economic concepts are significant to understand this process: i. Supply function: In a perfect competitive market, the shipowner maximizes his profit by operating the ship at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue (freight rate). an increase in freight rates will result in an increase in the speed of the ships and as a result the fleet productivity in increased together with the supply. Of course, speed is not the only way supply responds to freight rates. The shipowner may take advantage of the low freight rates and put his ship into dry dock or a storage 4

contract. At higher rates he may decide to return to the Arabian Sea from the Atlantic through the Suez Canal instead going via the cape. In addition, depending on the level of freight rates, ships are laid up and the supply side is reduced. On the long run, supply is regulated by the newbuilding and the scrapping activities. Factors determining laying up include age of ship (older ships have higher operating costs and are laid up at higher level of freight rates), size (bigger ships offer lower transport costs; s when a big and a small vessel compete for the same cargo, the bigger ship will have a lower lay up level). Finally, it is the relationship between speed and freight rates. ii. Demand function: in understanding the demand function it is important to understand the concept of the time frame. In the real world, the price at which buyers and sellers are prepared to trade depends on how much time they have to adjust their positions. There are 3 times periods to consider. The monetary equilibrium when the deal must be done immediately; the short run when there is time to adjust supply by short term measures such as lay up, reactivation, combined carriers switching markets or operating ships at a faster speed. Finally there is the long run when shipowners have time to take delivery of new ships and shippers have time to rearrange their supply sources.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Lula's Government in Brazil A New Left or The Old PopulismDocument18 pagesLula's Government in Brazil A New Left or The Old PopulismmelplaNo ratings yet

- CoMa Quiz 2Document21 pagesCoMa Quiz 2Antriksh JohriNo ratings yet

- Nemo Complete Documentation 2017Document65 pagesNemo Complete Documentation 2017Fredy A. CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Me Q-Bank FinalDocument52 pagesMe Q-Bank FinalHemant DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Defining compensation surveys and benchmark jobsDocument2 pagesDefining compensation surveys and benchmark jobsFarhan KabirNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis - Andinet - 2Document77 pagesFinal Thesis - Andinet - 2Gebiremariam DemisaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Exercise AnswersDocument9 pagesUnit 3 Exercise AnswersAnanda Siti fatimah100% (2)

- Production Management NotesDocument58 pagesProduction Management NotesRohan GentyalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Human CapitalDocument33 pagesChapter 8 Human CapitalGinnNo ratings yet

- For The Family How Class and Gender Shape Women S WorkDocument121 pagesFor The Family How Class and Gender Shape Women S WorkAlexandra ElenaNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Income Inequality in SingaporeDocument17 pagesEthnic Income Inequality in Singaporeyulin KeNo ratings yet

- Slides 13Document82 pagesSlides 13tegegn mogessie100% (1)

- Guy, Josephine - The Victorian Age - An Anthology of Sources and DocumentsDocument26 pagesGuy, Josephine - The Victorian Age - An Anthology of Sources and DocumentsMelina Natalia SuarezNo ratings yet

- ATOK Vs ATOKDocument1 pageATOK Vs ATOKida_chua8023No ratings yet

- Introduction to Applied Economics: Solving Economic ProblemsDocument13 pagesIntroduction to Applied Economics: Solving Economic ProblemsJecca JamonNo ratings yet

- Operations Strategy and CompetitivenessDocument21 pagesOperations Strategy and CompetitivenessAshish Chatrath100% (1)

- Trends in Human Resource ManagementDocument44 pagesTrends in Human Resource ManagementJustine Nicole L. EvangelioNo ratings yet

- Landes - What Do Bosses Really DoDocument40 pagesLandes - What Do Bosses Really DochapitamalaNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Decline of the Soviet Economy: Analysing Factors Behind Rapid Early Growth and Subsequent SlowdownDocument24 pagesThe Rise and Decline of the Soviet Economy: Analysing Factors Behind Rapid Early Growth and Subsequent Slowdownyezuh077No ratings yet

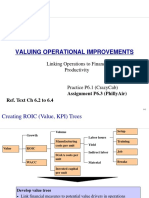

- 2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityDocument14 pages2 Linking Operations To Finance and ProductivityAidan HonnoldNo ratings yet

- Key Elements of Economic ActivityDocument14 pagesKey Elements of Economic ActivityClangClang Obsequio-ArintoNo ratings yet

- Ignou Important Questions MMPC 004Document2 pagesIgnou Important Questions MMPC 004catch meNo ratings yet

- Managerial Ability and Employee ProductivityDocument30 pagesManagerial Ability and Employee Productivitykhalil21No ratings yet

- Scope and Methods of EconomicsDocument4 pagesScope and Methods of EconomicsBalasingam PrahalathanNo ratings yet

- AsddsfaDocument202 pagesAsddsfaazay101No ratings yet

- Richard Kosolapov, Problems of Socialist TheoryDocument61 pagesRichard Kosolapov, Problems of Socialist TheoryGriffin Bur100% (1)

- Your Answer:: Operations and ProductivityDocument4 pagesYour Answer:: Operations and ProductivityPrabir AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Üds 2011 Sosyal Ilkbahar MartDocument16 pagesÜds 2011 Sosyal Ilkbahar MartDr. Hikmet ŞahinerNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 - The MacroeconomyDocument10 pagesUnit 9 - The MacroeconomyNaomiNo ratings yet

- Economics 1 Bridging Study Guide Part 3Document118 pagesEconomics 1 Bridging Study Guide Part 3Roger LinNo ratings yet