Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Uploaded by

Adrian Saliba VellaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Uploaded by

Adrian Saliba VellaCopyright:

Available Formats

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Hammurabi ((died c. 1750 BC) was the sixth king of Babylon from 1792 BC to 1750 BC.[1] He became the first king of the Babylonian Empire following the abdication of his father, Sin-Muballit, extending Babylon's control over Mesopotamia by winning a series of wars against neighboring kingdoms.[2] Although his empire controlled all of Mesopotamia at the time of his death, his successors were unable to maintain his empire. Hammurabi is known for the set of laws called Hammurabi's Code, one of the first written codes of law in recorded history. These laws were written on a stone tablet standing over eight feet tall (2.4 meters) that was found in 1901. Owing to his reputation in modern times as an ancient law-giver, Hammurabi's portrait is in many government buildings throughout the world.

History

Map showing the Babylonian territory upon Hammurabi's ascension in c. 1792 BC and upon his death in c.1750 BC Hammurabi was a First Dynasty king of the city-state of Babylon, and inherited the power from his father, Sin-Muballit, in c. 1792 BC.[3] Babylon was one of the many ancient city-states that dotted the Mesopotamian plain and waged war on each other for control of fertile agricultural land.[4] Though many cultures co-existed in Mesopotamia, Babylonian culture gained a degree of prominence among the literate classes throughout the Middle East.[5] The kings who came before Hammurabi had begun to consolidate rule of central Mesopotamia under Babylonian hegemony and, by the time of his reign, had conquered the city-states of Borsippa, Kish, and Sippar.[5] Thus Hammurabi ascended to the throne as the king of a minor kingdom in the midst of a complex geopolitical situation. The powerful kingdom of Eshnunna controlled the upper Tigris River while Larsa controlled the river delta. To the east lay the kingdom of Elam. To the north, Shamshi-Adad I was undertaking expansionistic wars,[6] although his untimely death would fragment his newly conquered Semitic empire.[7] The first few decades of Hammurabi's reign were relatively peaceful. Hammurabi used his power to undertake a series of public works, including heightening the city walls for defensive purposes, and expanding the temples.[8] In c. 1701 BC, the powerful kingdom of Elam, which straddled important trade routes across the Zagros Mountains, invaded the Mesopotamian plain.[9] With allies among the plain states, Elam attacked and destroyed the empire of Eshnunna, destroying a number of cities and imposing its rule on portions of the plain for the first time.[10] In order to consolidate its position, Elam tried to start a war between Hammurabi's Babylonian kingdom and the kingdom of Larsa.[11]

P age |1

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Hammurabi and the king of Larsa made an alliance when they discovered this duplicity and were able to crush the Elamites, although Larsa did not contribute greatly to the military effort.[11] Angered by Larsa's failure to come to his aid, Hammurabi turned on that southern power, thus gaining control of the entirety of the lower Mesopotamian plain by c. 1763 BC.[12] As Hammurabi was assisted during the war in the south by his allies from the north, the absence of soldiers in the north led to unrest.[12] Continuing his expansion, Hammurabi turned his attention northward, quelling the unrest and soon after crushing Eshnunna.[13] Next the Babylonian armies conquered the remaining northern states, including Babylon's former ally Mari, although it is possible that the 'conquest' of Mari was a surrender without any actual conflict.[14][15][16] In just a few years, Hammurabi had succeeded in uniting all of Mesopotamia under his rule.[16] Of the major city-states in the region, only Aleppo and Qatna to the west in Syria maintained their independence.[16] However, one stele of Hammurabi has been found as far north as Diyarbekir, where he claims the title "King of the Amorites".[17] Vast numbers of contract tablets, dated to the reigns of Hammurabi and his successors, have been discovered, as well as 55 of his own letters.[18] These letters give a glimpse into the daily trials of ruling an empire, from dealing with floods and mandating changes to a flawed calendar, to taking care of Babylon's massive herds of livestock.[19] Hammurabi died and passed the reins of the empire on to his son Samsu-Iluna in c. 1750 BC.[20]

Code of laws

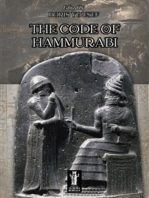

The upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws Hammurabi is best known for the promulgation of a new code of Babylonian law: the Code of Hammurabi. This was written on a stele, a large stone monument, and placed in a public place so that all could see it, although it is thought that few were literate. The stele was later plundered by the Elamites and removed to their capital, Susa; it was rediscovered there in 1901 and is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The code of Hammurabi contained 282 laws, written by scribes on 12 tablets. Unlike earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylon, and could therefore be read by any literate person in the city.[21]

P age |2

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

An inscription of the Code of Hammurabi The structure of the code is very specific, with each offense receiving a specified punishment. The punishments tended to be very harsh by modern standards, with many offenses resulting in death, disfigurement, or the use of the "Eye for eye, tooth for tooth" (Lex Talionis "Law of Retaliation") philosophy. Putting the laws into writing was important in itself because it suggested that the laws were immutable and above the power of any earthly king to change.[citation needed] The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence. However, there is no provision for extenuating circumstances to alter the prescribed punishment. A carving at the top of the stele portrays Hammurabi receiving the laws from the god Shamash or possibly Marduk[22], and the preface states that Hammurabi was chosen by the gods of his people to bring the laws to them. Parallels to this divine inspiration for laws can be seen in the laws given to Moses for the ancient Hebrews. Similar codes of law were created in several nearby civilizations, including the earlier Mesopotamian examples of Ur-Nammu's code, Laws of Eshnunna, and Code of Lipit-Ishtar, and the later Hittite code of laws.[23]

P age |3

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

The Code of Hammurabi (Codex Hammurabi) is a well-preserved ancient law code, created ca. 1790 BC (middle chronology) in ancient Babylon. It was enacted by the sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi.[1] One nearly complete example of the Code survives today, inscribed on a seven foot, four inch tall basalt stele[2] in the Akkadian language in the cuneiform script.[3]

Discovery

The stele containing the Code of Hammurabi was discovered in 1901 by the Egyptologist Gustav Jquier, a member of the expedition headed by Jacques de Morgan. The stele was discovered in what is now Khzestn, Iran (ancient Susa, Elam), where it had been taken as plunder by the Elamite king Shutruk-Nahhunte in the 12th century BC.[4] It is currently on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France.[5]

Hammurabi

Hammurabi (ruled ca. 1796 BC 1750 BC) decreed that he was chosen by the gods to deliver the law to his people. In the preface to the law code, he states, "Anu and Bel called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land."[6]

Law

The Code of Hammurabi was one of several sets of laws in the Ancient Near East.[7][8] Earlier collections of laws include the Code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (ca. 2050 BC), the Laws of Eshnunna (ca. 1930 BC) and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (ca. 1870 BC),[9] while later ones include the Hittite laws, the Assyrian laws, and Mosaic Law. These codes come from similar cultures in a relatively small geographical area, and they have passages which resemble each other. View of the back side of the stele. The code is often pointed to be a primary example of even a king not being able to change fundamental laws concerning the governing of a country which was the primitive form of what is now known as a constitution. The Babylonians and their neighbors developed the earliest system of economics that was fixed in a legal code, using a metric of various commodities. The early law codes from Sumer could be considered the first (written) economic formula, and have many attributes still in use in the current price system today, such as codified amounts of money for business deals (interest rates), fines in money for wrongdoing, inheritance rules and laws concerning how private property is to be taxed or divided.[10]

P age |4

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Examples

Here are eleven example laws, in their entirety, of the Code of Hammurabi, translated into English: If a man kills another man's son, his son shall be killed. If anyone ensnares another, putting a ban upon him, but he can not prove it, then he that ensnared him shall be put to death. If anyone brings an accusation against a man, and the accused goes to the river and leaps into the river, if he sinks in the river his accuser shall take possession of his house. But if the river proves that the accused is not guilty, and he escapes unhurt, then he who had brought the accusation shall be put to death, while he who leaped into the river shall take possession of the house that had belonged to his accuser. If anyone brings an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if a capital offense is charged, be put to death. If a builder builds a house for someone, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built falls in and kills its owner, then the builder shall be put to death.(Another variant of this is, If the owner's son dies, then the builder's son shall be put to death.) If a son slaps his father, his hand shall be cut off. If a man give his child to a nurse and the child dies in her hands, but the nurse unbeknown to the father and mother nurses another child, then they shall convict her of having nursed another child without the knowledge of the father and mother and her breasts shall be cut off. If anyone steals the minor son of another, he shall be put to death. If a man takes a woman to wife, but has no intercourse with her, this woman is no wife to him. If a man strikes a pregnant woman, thereby causing her to miscarry and die, the assailant's daughter shall be put to death. If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. There are 282 such laws in the Code of Hammurabi, each usually no more than a sentence or two. The 282 laws are bracketed by a Prologue in which Hammurabi introduces himself, and an Epilogue in which he affirms his authority and sets forth his hopes and prayers for his code of laws.

P age |5

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Magna Carta, also called Magna Carta Libertatum (the Great Charter of Freedoms), is an English legal charter, originally issued in the year 1215. It was written in Latin and is known by its Latin name. The usual English translation of Magna Carta is Great Charter. Magna Carta required King John of England to proclaim certain rights (pertaining to freemen), respect certain legal procedures, and accept that his will could be bound by the law. It explicitly protected certain rights of the King's subjects, whether free or fettered and implicitly supported what became the writ of habeas corpus, allowing appeal against unlawful imprisonment. Magna Carta was arguably the most significant early influence on the extensive historical process that led to the rule of constitutional law today in the English speaking world. Magna Carta influenced the development of the common law and many constitutional documents, including the United States Constitution.[1] Many clauses were renewed throughout the Middle Ages, and continued to be renewed as late as the 18th century. By the second half of the 19th century, however, most clauses in their original form had been repealed from English law. Magna Carta was the first document forced onto an English King by a group of his subjects (the barons) in an attempt to limit his powers by law and protect their privileges. It was preceded by the 1100 Charter of Liberties in which King Henry I voluntarily stated that his own powers were under the law. In practice, Magna Carta in the medieval period mostly did not limit the power of Kings; but by the time of the English Civil War it had become an important symbol for those who wished to show that the King was bound by the law. Magna Carta is normally understood to refer to a single document, that of 1215. Various amended versions of Magna Carta appeared in subsequent years however, and it is the 1297 version which remains on the statute books of England and Wales. INFLUENCES ON LATER CONSTITUTIONS Many later attempts to draft constitutional forms of government, including the United States Constitution, trace their lineage back to this source document. The United States Supreme Court has explicitly referenced Lord Coke's analysis of Magna Carta as an antecedent of the Sixth Amendment's right to a speedy trial.[14] Magna Carta has influenced international law as well: Eleanor Roosevelt referred to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as "a Magna Carta for all mankind". Magna Carta is thought to be the crucial turning point in the struggle to establish freedom and a key element in the transformation of constitutional thinking throughout the world. When Englishmen left their homeland to establish colonies in the new world, they brought with them charters that guaranteed they and their heirs would "have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects." (qtd. from wall of National Archives). In 1606,

P age |6

ASV

SOK

Hammurabi & Magna Carta

Sir Edward Coke, who drafted the Virginia Charter, had highly praised Magna Carta, which reflected many of its values and themes into the Virginia Charter (Howard 28). Colonists were also aware of their rights that came from Magna Carta. When American colonists raised arms against England, they were fighting not so much for new freedom, but to preserve liberties, many of which dated back to the 13th century Magna Carta. In 1787 when the representatives of America gathered to draft a constitution, they built upon the legal system they knew and admired: English common law that had evolved from Magna Carta (National Archives). The ideas addressed in the great charter that are found today are particularly obvious. The American Constitution is the "supreme law of the land," recalling the manner in which Magna Carta had come to be regarded as fundamental law. This heritage is quite apparent. In comparing Magna Carta with the Bill of Rights: the Fifth Amendment guarantees: "No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law."In addition, the United States Constitution included a similar writ in the Suspension Clause, article 1, section 9: "The privilege of the writ habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it." Written 575 years earlier, Magna Carta states, "No free man shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, not will we proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers and by the law of the land." (qtd. in Howard pg VI: Foreword). Each of these proclaim no man may be imprisoned or detained without proof that they did wrong.

P age |7

You might also like

- Hammurabis Code Lesson Plan 0Document11 pagesHammurabis Code Lesson Plan 0api-446600479No ratings yet

- Mesopotamian Legal Traditions and The Laws of HammurabiDocument29 pagesMesopotamian Legal Traditions and The Laws of HammurabirolfNo ratings yet

- The CrusadesDocument13 pagesThe CrusadesShaun KsNo ratings yet

- Max Duncker - The History of Antiquity - Volume 2Document346 pagesMax Duncker - The History of Antiquity - Volume 2Lucas MateusNo ratings yet

- What Is The Oldest Hebrew BibleDocument2 pagesWhat Is The Oldest Hebrew BibleEusebiu BorcaNo ratings yet

- The First Crusade PowerpointDocument9 pagesThe First Crusade Powerpointapi-246668105No ratings yet

- Lec 10 11 - MESOPOTAMIADocument31 pagesLec 10 11 - MESOPOTAMIAAMNA NAVEED100% (1)

- Roman Constitutional HistoryDocument17 pagesRoman Constitutional HistoryNaomi VimbaiNo ratings yet

- Translated Georgian text explores Adam and Eve's expulsion from EdenDocument19 pagesTranslated Georgian text explores Adam and Eve's expulsion from EdenVictorN2No ratings yet

- Natural Law and Positive Law (1949)Document19 pagesNatural Law and Positive Law (1949)akinvasionNo ratings yet

- Late Babylonian Uruk 2011Document11 pagesLate Babylonian Uruk 2011jimjorgeNo ratings yet

- Truth About Socialism CommunismDocument153 pagesTruth About Socialism CommunismAnonymous erItngH13lNo ratings yet

- Construction of The ZigguratDocument4 pagesConstruction of The ZigguratakshayNo ratings yet

- Charlemagne "Charles The Great" and The Holy Roman Empire: Lesson 11-1Document17 pagesCharlemagne "Charles The Great" and The Holy Roman Empire: Lesson 11-1Janeza Cris CastroNo ratings yet

- Egypt: New Kingdom Egypt To The Death of Thutmose IVDocument54 pagesEgypt: New Kingdom Egypt To The Death of Thutmose IVRaul Antonio Meza JoyaNo ratings yet

- Consular convention Between the People's Republic of China and The United States of AmericaFrom EverandConsular convention Between the People's Republic of China and The United States of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Helaman 6Document2 pagesHelaman 6Greg CarlstonNo ratings yet

- Babylonian Records of Judah's DeclineDocument3 pagesBabylonian Records of Judah's DeclineKarina LoayzaNo ratings yet

- The Ur Nammu Law CodeDocument2 pagesThe Ur Nammu Law CodeSpiritually Gifted100% (1)

- Aarons' Rod EBR Sample ArticleDocument3 pagesAarons' Rod EBR Sample ArticlemackoypogiNo ratings yet

- 3056 OldTest TimelineDocument4 pages3056 OldTest TimelineMGTOW warriorNo ratings yet

- Histarc 161207055614 PDFDocument48 pagesHistarc 161207055614 PDFcarolmenzlNo ratings yet

- Mayflower Compact Worksheet - RevisedDocument2 pagesMayflower Compact Worksheet - Revisedapi-234801058100% (1)

- Battle of Bible 1Document68 pagesBattle of Bible 1Advent Eden Sihono100% (1)

- Book of The Prophet IsaiahDocument81 pagesBook of The Prophet IsaiahBenjamin Thompson100% (2)

- African Empires & Swahili StatesDocument5 pagesAfrican Empires & Swahili Statesganzistyle96No ratings yet

- Complete Class NotesDocument83 pagesComplete Class NotesOlivia MaoNo ratings yet

- Covenant, Treaty, and Prophecy in the Old TestamentDocument9 pagesCovenant, Treaty, and Prophecy in the Old Testamentcarlos sumarchNo ratings yet

- Moab and AmmonDocument64 pagesMoab and Ammonjld4444100% (1)

- Book Prologue Section 3Document6 pagesBook Prologue Section 3api-217748858No ratings yet

- The Origins of Transhumant Pastoralism in Temperate SE Europe - Arnold GreenfieldDocument212 pagesThe Origins of Transhumant Pastoralism in Temperate SE Europe - Arnold Greenfieldflibjib8No ratings yet

- Farsi-Nameh: Abridged English VersionDocument64 pagesFarsi-Nameh: Abridged English VersionArash Monzavi-Kia100% (2)

- HammurabiDocument51 pagesHammurabikhadijabugtiNo ratings yet

- Code of Hammurabi - BreannaDocument5 pagesCode of Hammurabi - Breannaapi-244148224No ratings yet

- Hammurabi's Code and the Laws of MosesDocument11 pagesHammurabi's Code and the Laws of MosesClark MoïseNo ratings yet

- Hammurabi DocumentsDocument6 pagesHammurabi DocumentsjonasNo ratings yet

- Code of Hammurabi AssignmentDocument2 pagesCode of Hammurabi AssignmentJohn PernitoNo ratings yet

- Code of Hammurabi ancient Babylonian legal textDocument2 pagesCode of Hammurabi ancient Babylonian legal textWolfMensch1216No ratings yet

- Codul Lui HammurabiDocument10 pagesCodul Lui HammurabiDana HarangusNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - The Code of Hammurabi, The Code of Ur NammuDocument5 pagesChapter 1 - The Code of Hammurabi, The Code of Ur Nammukim ryan uchiNo ratings yet

- OLCPCAD1 (Compressed)Document72 pagesOLCPCAD1 (Compressed)Ken KenNo ratings yet

- Hammurabi’s Code: Fair or CruelDocument2 pagesHammurabi’s Code: Fair or Cruelhyuun hyaoniNo ratings yet

- Legends of the Ancient World: The Life and Legacy of HammurabiFrom EverandLegends of the Ancient World: The Life and Legacy of HammurabiNo ratings yet

- 2 1 HammurabiDocument1 page2 1 Hammurabiapi-98469116No ratings yet

- History of Punishment and Corrections in Hammurabi's CodeDocument83 pagesHistory of Punishment and Corrections in Hammurabi's CodeJohnpatrick DejesusNo ratings yet

- The Legendary Kings of Babylon: Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar IIFrom EverandThe Legendary Kings of Babylon: Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar IIRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Code of Hammura-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesCode of Hammura-WPS OfficeJommel Gerola AcabadoNo ratings yet

- The God of the Habiru: A Look at Sumerian SocietyDocument24 pagesThe God of the Habiru: A Look at Sumerian Societyredwasp_korneelNo ratings yet

- Hammurabi - The CodeDocument32 pagesHammurabi - The CodezoommqNo ratings yet

- HammurabiDocument8 pagesHammurabiRizka DvmNo ratings yet

- King Hammurabi (Reigning C. 1792-1750 BCE) - Jabber A. CairodingDocument2 pagesKing Hammurabi (Reigning C. 1792-1750 BCE) - Jabber A. CairodingJabber CairodingNo ratings yet

- Ancient WK 2 Mesopotamia BabylonianDocument10 pagesAncient WK 2 Mesopotamia BabylonianRebecca Currence100% (4)

- The Legal Systems of The WorldDocument80 pagesThe Legal Systems of The WorldCarlyn Belle de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 7 - The Legal Systems of The WorldDocument23 pages7 - The Legal Systems of The WorldCzarina BantayNo ratings yet

- Babylonian and Neo Babylonian EmpireDocument2 pagesBabylonian and Neo Babylonian Empireapi-208379744No ratings yet

- History of Law Codes and PrecedentDocument2 pagesHistory of Law Codes and PrecedentVincent BajaNo ratings yet

- World History II Chapter 3 Section 2 The First Empires2Document25 pagesWorld History II Chapter 3 Section 2 The First Empires2Ery DiazNo ratings yet

- CV and Interview Guide BALPADocument16 pagesCV and Interview Guide BALPAAdrian Saliba VellaNo ratings yet

- PowerMILL 2013 EnhancementsDocument2 pagesPowerMILL 2013 EnhancementsAdrian Saliba VellaNo ratings yet

- The Inside Track: Becoming A PilotDocument25 pagesThe Inside Track: Becoming A PilotAdrian Saliba VellaNo ratings yet

- 2 Casting FormingDocument56 pages2 Casting Formingmanojpravin123No ratings yet

- Divorce Is Not Good But The Option To Divorce Should Be LegalizedDocument2 pagesDivorce Is Not Good But The Option To Divorce Should Be LegalizedAdrian Saliba VellaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy (I) - Ethics 1 - The Identity and Moral Status of The Human EmbryoDocument4 pagesPhilosophy (I) - Ethics 1 - The Identity and Moral Status of The Human EmbryoAdrian Saliba VellaNo ratings yet

- Bersifat Ingin Tahu Kelestarian Alam Sekitar Mengaplikasi Audio 1,2 Dan3 (Lagu Salam Sejahtera) Buku Teks: Ms 4Document7 pagesBersifat Ingin Tahu Kelestarian Alam Sekitar Mengaplikasi Audio 1,2 Dan3 (Lagu Salam Sejahtera) Buku Teks: Ms 4farahNo ratings yet

- English Lesson Plan 2 W Self ReflectionDocument4 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan 2 W Self Reflectionapi-347772899No ratings yet

- Predicting Home Prices in BangaloreDocument18 pagesPredicting Home Prices in Bangalorefarrukhbhatti78No ratings yet

- Pleasanter or More Pleasant Comparative AdjectivesDocument3 pagesPleasanter or More Pleasant Comparative AdjectivesAli S HaniNo ratings yet

- Em78p153s PDFDocument54 pagesEm78p153s PDFMarian MarinNo ratings yet

- Creative Design and Innovation (CDI) Assessment CheckpointDocument5 pagesCreative Design and Innovation (CDI) Assessment CheckpointajwanNo ratings yet

- (2019) - Brešar Matej. Undergraduate Algebra. A Unified ApproachDocument337 pages(2019) - Brešar Matej. Undergraduate Algebra. A Unified ApproachJorge JG100% (3)

- An Integrated EDA Software Package for Electronics DesignDocument7 pagesAn Integrated EDA Software Package for Electronics DesignRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- "One Good Friend Is Better Than A Thousand Poor Ones" To What Extent Is This Statement True? DiscussDocument1 page"One Good Friend Is Better Than A Thousand Poor Ones" To What Extent Is This Statement True? DiscussEriqNo ratings yet

- Matlab Tutorial and Linear Algebra ReviewDocument34 pagesMatlab Tutorial and Linear Algebra ReviewRoihanNstNo ratings yet

- Final 1 - Sousa Chapter 4Document3 pagesFinal 1 - Sousa Chapter 4api-429757438No ratings yet

- Faith 5 Matt 20-10-16 Handout 081912Document2 pagesFaith 5 Matt 20-10-16 Handout 081912alan shelbyNo ratings yet

- Word Games and Puzzles PDFDocument28 pagesWord Games and Puzzles PDFAmarendra Kumar AvinashNo ratings yet

- Guess Bible CharacterDocument40 pagesGuess Bible CharacterBlibli EulishNo ratings yet

- Complete Act Grammar Rules-8-9Document2 pagesComplete Act Grammar Rules-8-9daliaNo ratings yet

- Practical Lab No.12Document6 pagesPractical Lab No.12Vishal KumarNo ratings yet

- Niruktaślokavārttika by Kōndayūr Nīlaka A - A StudyDocument4 pagesNiruktaślokavārttika by Kōndayūr Nīlaka A - A StudySaranya KNo ratings yet

- Subject Verb AgreementDocument18 pagesSubject Verb AgreementBasilas Ace Dominic T.No ratings yet

- Essay Scaffolds-Natural OrderDocument2 pagesEssay Scaffolds-Natural OrderRenaNo ratings yet

- Saptrang TM 6Document48 pagesSaptrang TM 6Chaitanya AralkarNo ratings yet

- English Literature McqsDocument11 pagesEnglish Literature McqsEshal Fatima100% (4)

- JainismDocument11 pagesJainismlakshmimadhuri12No ratings yet

- Verb Tenses. 1. Put The Verbs in Brackets in The PRESENT SIMPLE or The PRESENT CONTINUOUSDocument3 pagesVerb Tenses. 1. Put The Verbs in Brackets in The PRESENT SIMPLE or The PRESENT CONTINUOUSpsolguiNo ratings yet

- Balvatika, CL 1 Txtbooks & Jadui PitaraDocument8 pagesBalvatika, CL 1 Txtbooks & Jadui PitararajNo ratings yet

- Digraphs and DiphthongsDocument4 pagesDigraphs and DiphthongsMuhammad Irfan AbidNo ratings yet

- hUMOR IN ENGLISH BOOK ICCSALDocument4 pageshUMOR IN ENGLISH BOOK ICCSALFithriyah Inda Nur Abida ABIDANo ratings yet

- Windows 8 Vs Windows 8.1.Document44 pagesWindows 8 Vs Windows 8.1.cordial2No ratings yet

- English8 q2 Mod3 CompareandContrastSameTopicinDifferentMultimodalTexts v2Document26 pagesEnglish8 q2 Mod3 CompareandContrastSameTopicinDifferentMultimodalTexts v2Ma'am CharleneNo ratings yet

- Maurice BlanchotDocument31 pagesMaurice BlanchotcNo ratings yet

- Parson AdamsDocument5 pagesParson Adamstejuasha26No ratings yet