Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HRM

Uploaded by

Kinshuk GuptaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HRM

Uploaded by

Kinshuk GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

Executive Summary Downsizing or doing layoffs is a toxic solution.

Used sparingly and with plannin g downsizing can be an organizational lifesaver, but when layoffs are used repea tedly without a thoughtful strategy, downsizing can destroy an organization's ef fectiveness. How you treat people really matters - to the people who leave and t he people who remain. One outcome of downsizing must be to preserve the organization's intellectual ca pital. How downsized employees are treated directly affects the morale and retention of valued, high-performing employees who are not downsized. Downsizing should never be used as a communication to financial centers or inves tors of the new management's tough-minded, no-nonsense style of management -- th e cost of downsizing far outweighs any benefits thus gained. Introduction Make no mistake: downsizing is extremely difficult. It taxes all of a management team's resources, including both business acumen and humanity. No one looks for ward to downsizing. Perhaps this is why so many otherwise first-rate executives downsize so poorly. They ignore all the signs pointing to a layoff until it's to o late to plan adequately; then action must be taken immediately to reduce the f inancial drain of excess staff. The extremely difficult decisions of who must be laid off, how much notice they will be given, the amount of severance pay, and how far the company will go to h elp the laid-off employee find another job are given less than adequate attentio n. These are critical decisions that have as much to do with the future of the o rganization as they do with the future of the laid-off employees. So what happens? These decisions are handed to the legal department, whose prima ry objective is to reduce the risk of litigation, not to protect the morale and intellectual capital of the organization. Consequently downsizing is often execu ted with a brisk, compassionless efficiency that leaves laid-off employees angry and surviving employees feeling helpless and demotivated. Helplessness is the enemy of high achievement. It produces a work environment of withdrawal, risk-averse decisions, severely impaired morale, and excessive blam ing. All of these put a stranglehold upon an organization that now desperately n eeds to excel. Avoiding the Pitfalls of Downsizing Ineffective methods of downsizing abound. Downsizing malpractices such as those that follow are common; they are also inefficient and very dangerous. Allowing Legal Concerns to Design the Layoff Most corporate attorneys will advise laying off employees on a last-hired, first -fired basis across all departments. The method for downsizing that is most clea rly defensible in a court of law, for example, is to lay off 10 percent of emplo yees across all departments on a seniority-only basis. This way no employee can claim that he or she was dismissed for discriminatory reasons. Furthermore, attorneys advise against saying anything more than what's absolutel y necessary to either the departing employees or the survivors. This caution is designed to protect the company from making any implied or explicit promises tha t aren't then kept. By strictly scripting what is said about the layoffs, the co mpany is protecting itself from verbal slips by managers who are themselves stre ssed at having to release valued employees.

This approach may succeed from a legal perspective, but not necessarily from the larger and more important concern of organizational health. First, laying off e mployees by a flat percentage across different departments is irrational. How ca n it be that accounting can cope with the same proportion of fewer employees as human resources? Could it be that one department can be externalized and the oth er left intact? The decision of how many employees to lay off from each departme nt should be based on an analysis of business needs, not an arbitrary statistic. The concept of laying off employees strictly on the basis of seniority is also i rrational. The choice of employees for a layoff should be based on a redistribut ion of the work, not the date the individual employee was hired. Sometimes an em ployee of 18 months has a skill far more valuable than one with 18 years' senior ity. See More Pitfalls of Downsizing -------------------------------------------------------------------------------Alan Downs is a management psychologist and consultant who specializes in strate gic human resources planning and helping business executives reach their maximum potential. He has authored several books, including AMACOM's Corporate Executio ns (1995), the much-acclaimed expose on downsizing, The Seven Miracles of Manage ment (Prentice Hall,1998), and The Fearless Executive (AMACOM 2000). Downs is wi dely sought for interviews by newspaper, TV, and radio broadcasts. He has also w ritten on management topics for numerous national newspapers and trade publicati ons, including Management Review and Across the Board. Give as Little Notice as Possible Out of fear and guilt many executives choose to give employees as little forewar ning as possible about an upcoming layoff or downsizing. Managers fear that if e mployees know their fate ahead of time, they might become demoralized and unprod uctive -- they may even sabotage the business. However, there is no documented e vidence that advance notice of a layoff increases the incidence of employee sabo tage. The lack of advance notice about downsizing, however, does dramatically increase mistrust of management among surviving workers. Trust is based on mutual respec t. When employees discover what has been brewing without their knowledge or inpu t (and they will when the first person is let go), they see a blatant disrespect for their integrity, destroying trust. By not giving employees information that could be enormously helpful to them in planning their own lives, management ini tiates a cycle of mistrust and helplessness that can be very destructive and req uire years to correct. Afterward Act as if Nothing Happened Many managers believe that after a layoff, the less said about it the better. Wi th luck, everyone will just forget and move on. Why keep the past alive? The rea lity is, surviving employees will talk about what's happened whether the managem ent team does or doesn't. The more the company tries to suppress these discussio ns and act as if nothing has happened, the more subversive the discussion become s. Remaining employees will act as a consequence of what has happened regardless of whether the management does. Recovery from a layoff is greatly hastened if managers and employees are allowed to speak their minds freely about what's happened. In fact, it can be a great o pportunity for the team of surviving employees to pull together and renew ties.

When management refuses to acknowledge what has really taken place, it appears e mphatically heartless, feeding the employees' sense of helplessness. If manageme nt won't talk about it even after the fact, what else is it hiding? "To downsize effectively you have to have empathy with the people who are losing their jobs. " (Percy Barnevik) Downsizing Effectively When faced with an organization that isn't functioning at optimal efficiency and thinking that a layoff is needed, there are a few key principles to keep in min d. Observing these principles won't completely eliminate the dangers of downsizi ng, but they will help to avoid the common pitfalls of a poorly planned layoff. Is the Problem too Many People or too Little Profit? The critical first question to ask before any layoff is: Is the need for this la yoff driven by having too many employees or too little profit? If it's too littl e profit, this is the first warning sign that your company isn't ready for a lay off. Using a layoff solely as a cost cutting measure is utterly foolish: throwin g away valuable talent and organizational learning by dumping employees only mak es a bad situation worse. When your business lacks revenue, annihilating intelle ctual capital and thus reducing the efficiency of remaining resources as well as the potential for future growth is not the solution. If the answer is too many employees, then you've begun the process of a well-tho ught-out strategy for change. To legitimately determine if you have too many emp loyees, look at the organization's business plan, not its head count. What produ ct and services will you be offering? Which of these products and services is li kely to be profitable? What talent will you need to run the new organization? Th ese questions will help you plan for the post-layoff future. These issues will e nable a quick turnaround from the inevitably negative effects of downsizing to p ositive growth in value and efficiency. What will the Post-Layoff Company Look Like? Having a clear, well-defined vision of the company is imperative before the layo ff is executed. Management should know what it wants to accomplish, where the em phasis will be in the new organization, and what staff will be needed. Without being directed according to a clear vision of the future, the new organi zation is likely to carry forward some of the same problems that initially creat ed the need for the layoff. Unfortunately, many managers underestimate the momen tum of the old organization to recreate the same problems anew. Unless there is a clearly defined, shared vision of the new company among the entire management team, the past will be likely to sabotage the future and create a cycle of repea ted layoffs with little improvement in organizational efficiency. Always Respect People's Dignity The methods employed in many poorly executed layoffs treat employees like childr en. Information is withheld and doled out. Managers' control over their employee s is violated. Human resource representatives scurry around from one hush-hush m eeting to another. How management treats laid-off employees is how it vicariousl y treats remaining employees -- everything you do in a layoff is done in the are na, with everyone observing. How laid-off employees are treated is how surviving employees assume they may be treated. Why does this matter? Because successfully planning for the new organization wil l keep it going and improve its results. You must keep that exceptional talent,

who are also the employees most marketable to other organizations. When they see the company treating laid-off employees poorly, they'll start looking for a bet ter place to work, fearing their heads will be next to roll. Respect the Law While it's important not to allow the legal department to design a layoff, it's nevertheless important that you respect the employment laws. In different countr ies such laws include entitlements tied to civil rights, age discrimination, dis abilities, worked adjustment, and retraining. These laws are important and shoul d be respected for what they intend as well as what they prescribe -- or proscri be. If you have planned your lay-off according to business needs, and not on hea d count or seniority, you should have no problem upholding the law. You will alm ost always find yourself in legal trouble when you base your layoff on factors o ther than business needs. Mini-cases: Good Examples During the merger of BB&T Financial Corporation and Southern National Corporatio n, redundant positions were eliminated through the strategic use of a hiring fre eze. Hewlett-Packard implemented a so-called fortnight program in which all employees were asked to take one day off without pay every two weeks until business reven ue increased. Mini-case: Bad Example Scott Paper conducted a layoff of 10,500 employees in the mid-1990s. In the year s that followed Scott was unable to introduce any new products and saw a dramati c decrease in profitability, until it was eventually bought out by competitor Ki mberly-Clark. Making it Happen Downsizing successfully is immensely difficult. The following ideas can help to focus thinking for anyone considering such a move. Treat all employees with respect. Communicate too much rather than withhold info rmation. Research applicable laws and follow the spirit of the legislation. Afterward, give employees the psychological space to accept, and discuss, what h as happened. Conclusion There are two important factors to keep in mind when planning a layoff: respecti ng employee dignity and business planning. No one, from the mailroom to the boar d-room, enjoys downsizing; but when the need for a reduction in staff is unavoid able, a layoff can be accomplished in such a way that the problem is fixed and t he organization excels. ------------Alternatives to Layoffs Layoffs, a short term fix, detrime Layoffs are done to save money. Unfortunately, they are usually a short term fix , detrimental to the company. So why do so many companies persist in using layof fs as a first choice for cutting costs, and what are some of the alternatives. We missed our numbers

Sometimes things don't work out as forecast. Clients delay purchases. Suppliers raise prices. Competitors steal market share. Quarterly, at least in the US, com panies have to face the forecasts they made. Public companies have to face Wall Street too. Investor don't like surprises. They don't value executives who miss their numbers. And they expect quick and strong action to addresses the issues. Unfortunately, the very pressure to take action quickly ultimately works against their own best interest. Pressing for immediate action forces executives to cut costs, as opposed to raising income. Foolishly therefore, reducing the workforc e has become an automatic response for companies who need to cut costs to look g ood for Wall Street. It's wrong. It's counter-productive. It should be a last re sort, not a first choice for a skilled executive. Job cuts don't save money In "Organizational downsizing: Constraining, cloning, learning" (McKinley, Willi am, Schick, Allen G., Sanchez, Carol M. (1995) ISSN: 0896-3789) the authors poin t out that "while downsizing has been viewed primarily as a cost reduction strat egy, there is considerable evidence that downsizing does not reduce expenses as much as desired, and that sometimes expenses may actually increase. More than th irty years ago, James Lincoln warned that the costs of layoffs generally outweig h the payroll savings to be gained from them." Job cuts reduce performance John Dorfman, a Boston-based money manager, analyzed the post-layoff performance of a sampling of companies. The review included 11 to 34 months of data for the companies sampled. His article Job Cuts Often Fail to Bolster Stocks reports an average performance gain by the companies that had announced job cuts at 0.4% w hile the performance for the S&P 500 during the comparable time period was a gai n was 29.3%. Prize-winning photographer Gary Green, was laid off by the Akron Beacon, but rem ained a shareholder in Knight Rider, the company that owned the paper. He addres sed the annual stockholder meeting saying "As a victim of the layoffs, I am the one suffering today. However, the shareholders are the ones who will suffer in t he long run. The talent will leave. Circulation and revenue will continue to dro p. The shareholders will be left with a worthless product. Is this the future we want for our company?" Protecting your investments Many companies fail to realize that they have a tremendous long-term capital inv estment in their employees. While wages and benefits clearly are an expense item on the budget, they should be thought of more as payments on the capital of emp loyees skill and dedication. The same care, thought, and rigorous analysis shoul d be given to decisions on the capital invested in employees as would be to a fa ctory or a production line. A factory can be reopened, or a production line rest arted, much more easily than employees trust in their management or faith in the company's vision can be restored after a layoff. Layoff announcements speak of jobs eliminated or percentage reduction of the wor kforce, but behind those pretty words are are the company's people. Whether the company is able to continue to compete effectively, is able to fulfil the promis e the layoffs make to the investors, will continue to generate the innovation re quired to survive in the marketplace depends on those people. It depends on thos e who are left after the layoffs, those of them that choose to remain after the layoffs are completed. It depends on how they feel about how others were treated and how they themselves might be treated in the next round of layoffs, which ma y come. A company may lay off employees it considers the low end producers, but in doing so it creates a climate of personnel uncertainty. That uncertainty causes other

s to leave. The first people to leave due to uncertainty in the company are the best people, because they can always get another job somewhere else. The climate of uncertainty that follows a layoff, therefore, always guarantees a reduction in the quality of the staff, not just the quantity. Companies contemplating layoffs need to consider more than just the hoped for co st savings from a layoff. They need to consider, and plan for, the less obvious effects. They need to consider the reduced morale and the reduced performance an d innovation it will bring. They need to consider the reduced quality of the com pany's overall workforce that will result. Restructuring does work There are alternatives to across the board layoffs that do work to reduce costs. One of the most effective and most immediate of these is restructuring. Often, when job cuts are undertaken in order to pacify the investors, the announcements talk about the cuts as part of a "streamlining" or "restructuring", but they re fer only to the people involved. There are other aspects of the company's busine ss that need to be restructured as well. These often include things such as clos ing of obsolete plants or branches, administrative overhauls, selling of non-cor e operations, or improving internal processes. Dorfman believes that when a stock shows a gain over the year or two following c uts, it is often the non-layoff elements in the restructuring package that deser ve the credit. Arguably, these kinds of things take longer to effect the bottom line than cutti ng out the salaries of the laid off employees. However, when one considers the c osts of severance payments to those employees, continued health care payments fo r some, increased unemployment charges as a result of the layoffs, reduced produ ctivity following the layoffs, etc., that may not be valid. Typically companies will take a "one-time charge" against earnings to cover the layoff, which clears these costs from the books quickly. In reality the change w on't make any difference until at least the next quarterly report. In that same period, other, slower changes could have been implemented and have shown similar cost reductions. The difference then is mainly cosmetic. Making the numbers loo k good quickly (layoffs) so Wall Street is happy versus slower method of restruc turing the business that preserve the company's significant investment in its em ployee capital. Manage This Issue Find and fix the problem. Don't just cut jobs to look good to the investors. Mak e the changes that will make the company better instead of damaging the very thi ng that made the company successful in the first place, its employees. Restructure the business to make it better. If a function is not contributing to the company's success get rid of it, but cut from the head down, not from the b ottom up. Make sure remaining employees clearly understand the selection process that was used to cut under-performing units or functions no longer sufficiently valuable to the company. If you have any questions or comments about this article, or if there is an issu e you would like us to address, please post them on our Management Forum to shar e with the entire group.

You might also like

- Downsizing With Care and RespectDocument9 pagesDownsizing With Care and Respectdali77No ratings yet

- Dismissing an Employee: Expert Solutions to Everyday ChallengesFrom EverandDismissing an Employee: Expert Solutions to Everyday ChallengesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Emergency Management 9-1-1: In God We Trust, All Others Must Be MonitoredFrom EverandEmergency Management 9-1-1: In God We Trust, All Others Must Be MonitoredNo ratings yet

- Preventing Strategic Gridlock (Review and Analysis of Harper's Book)From EverandPreventing Strategic Gridlock (Review and Analysis of Harper's Book)No ratings yet

- Explore Data-Driven Solutions for RetentionDocument6 pagesExplore Data-Driven Solutions for RetentionChaitanya DachepallyNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Study On Role of HR in RecessionDocument3 pagesA Project Report On Study On Role of HR in RecessionSolai RajanNo ratings yet

- Performance Management: Is it Time to Coach, Counsel or TerminateFrom EverandPerformance Management: Is it Time to Coach, Counsel or TerminateNo ratings yet

- interim management for beginners: exclusive insight for the interim manager of tomorrow. Well-founded. Instructive. Pioneering.From Everandinterim management for beginners: exclusive insight for the interim manager of tomorrow. Well-founded. Instructive. Pioneering.No ratings yet

- Ruthless Execution (Review and Analysis of Hartman's Book)From EverandRuthless Execution (Review and Analysis of Hartman's Book)No ratings yet

- Employee AttritionDocument97 pagesEmployee Attritiondec3100% (3)

- Dealing with Dismissal: Practical advice for employers and employeesFrom EverandDealing with Dismissal: Practical advice for employers and employeesNo ratings yet

- Delegation and Supervision (The Brian Tracy Success Library)From EverandDelegation and Supervision (The Brian Tracy Success Library)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Core Leadership and Management Skills, Tips & Strategy Handbook V2: Strength based leadership coaching on habits, principles, theory, application, skill development & training for driven men and womenFrom EverandCore Leadership and Management Skills, Tips & Strategy Handbook V2: Strength based leadership coaching on habits, principles, theory, application, skill development & training for driven men and womenNo ratings yet

- Billionaire Thought Models in Business: Replicate the thinking Systems, Mental Capabilities and Mindset of the Richest and Most Influential Businessmen to Earn More by Working LessFrom EverandBillionaire Thought Models in Business: Replicate the thinking Systems, Mental Capabilities and Mindset of the Richest and Most Influential Businessmen to Earn More by Working LessNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Downsizing On Corporate CultureDocument4 pagesThe Impact of Downsizing On Corporate Culturesmitamali94No ratings yet

- Effect of Downsizing On Employees Morale 1Document286 pagesEffect of Downsizing On Employees Morale 1Christine EnnisNo ratings yet

- Motivation (The Brian Tracy Success Library)From EverandMotivation (The Brian Tracy Success Library)Rating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (6)

- Leadership and Drive: Best Practices for Cultivating High Performance TeamsFrom EverandLeadership and Drive: Best Practices for Cultivating High Performance TeamsNo ratings yet

- It's All About People!: A Practical Guide to Develop a Dynamic Safety CultureFrom EverandIt's All About People!: A Practical Guide to Develop a Dynamic Safety CultureNo ratings yet

- AttritionDocument10 pagesAttritionPriyaNo ratings yet

- The Staffieri Principles: A Philosophy in Employee ManagementFrom EverandThe Staffieri Principles: A Philosophy in Employee ManagementNo ratings yet

- Scaling Up and Coping With FailureDocument2 pagesScaling Up and Coping With FailureJayan PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Managing to Make a Difference: Discovering Employees as ColleaguesFrom EverandManaging to Make a Difference: Discovering Employees as ColleaguesNo ratings yet

- Being the Action-Man in Business: How to start making things happen today!From EverandBeing the Action-Man in Business: How to start making things happen today!No ratings yet

- Main Content - KA-1 ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZDocument53 pagesMain Content - KA-1 ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZPrerna SocNo ratings yet

- Coaching, Counseling and Mentoring: How to Choose and Use the Right Technique to Boost Employee PerformanceFrom EverandCoaching, Counseling and Mentoring: How to Choose and Use the Right Technique to Boost Employee PerformanceNo ratings yet

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Change Management (including featured article "Leading Change," by John P. Kotter)From EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Change Management (including featured article "Leading Change," by John P. Kotter)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- 5 Reasons People Get Laid Off - HBR Jan 2024Document6 pages5 Reasons People Get Laid Off - HBR Jan 2024peyush bhardwajNo ratings yet

- Free Range Management: How to Manage Knowledge Workers and Create SpaceFrom EverandFree Range Management: How to Manage Knowledge Workers and Create SpaceNo ratings yet

- Professionalizing Strategic Systems Management for Business and Organizational Success: Introducing the Ccim Three-Leg StoolFrom EverandProfessionalizing Strategic Systems Management for Business and Organizational Success: Introducing the Ccim Three-Leg StoolNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Employee Retention in IT IndustryDocument71 pagesFactors Affecting Employee Retention in IT Industryrabi_kungleNo ratings yet

- To Prevent Burnout Hire Better BossesDocument3 pagesTo Prevent Burnout Hire Better BossesMatee PatumasootNo ratings yet

- The Front-line Manager: Practical Advice for SuccessFrom EverandThe Front-line Manager: Practical Advice for SuccessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Create Magic At Work: Practical Tools To Ignite Human ConnectionFrom EverandCreate Magic At Work: Practical Tools To Ignite Human ConnectionNo ratings yet

- Summary Of Traction: Get a Grip on Your Business- A guide to Gino Wickman’s bookFrom EverandSummary Of Traction: Get a Grip on Your Business- A guide to Gino Wickman’s bookNo ratings yet

- Employee Attrition Is A Costly Dilemma For All Organizations. Control Attrition With Effective Communication - Build Strong, High-Performance TeamsDocument10 pagesEmployee Attrition Is A Costly Dilemma For All Organizations. Control Attrition With Effective Communication - Build Strong, High-Performance TeamsshiprabarapatreNo ratings yet

- Employees RedundancyDocument3 pagesEmployees RedundancyHamza TahirNo ratings yet

- Lean Six Sigma: The Ultimate Guide to Lean Six Sigma, Lean Enterprise, and Lean Manufacturing, with Tools Included for Increased Efficiency and Higher Customer SatisfactionFrom EverandLean Six Sigma: The Ultimate Guide to Lean Six Sigma, Lean Enterprise, and Lean Manufacturing, with Tools Included for Increased Efficiency and Higher Customer SatisfactionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Management: Getting The Best Out of OthersDocument12 pagesManagement: Getting The Best Out of OthersAmr essamNo ratings yet

- Effect of Downsizing On Employees Morale 1Document74 pagesEffect of Downsizing On Employees Morale 1SANDEEP ARORA100% (3)

- How To Solve DiDocument2 pagesHow To Solve DiKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- MBA HandbookDocument20 pagesMBA HandbookKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- Cat SyllabusDocument2 pagesCat SyllabusKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- Cat GKDocument13 pagesCat GKKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- CATch Me If You CanDocument26 pagesCATch Me If You CanKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- Indian Bureaucracy and Business EnvironmentDocument5 pagesIndian Bureaucracy and Business EnvironmentKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- Other AttachmentDocument16 pagesOther AttachmentKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- Z and T TestsDocument31 pagesZ and T TestsmsulgadleNo ratings yet

- Production Analysis For Punjab National BankDocument15 pagesProduction Analysis For Punjab National BankKinshuk GuptaNo ratings yet

- Cipac MT 185Document2 pagesCipac MT 185Chemist İnançNo ratings yet

- Cell City ProjectDocument8 pagesCell City ProjectDaisy beNo ratings yet

- Nursing Plan of Care Concept Map - Immobility - Hip FractureDocument2 pagesNursing Plan of Care Concept Map - Immobility - Hip Fracturedarhuynh67% (6)

- Fuck Your LawnDocument86 pagesFuck Your Lawnhuneebee100% (1)

- MR23002 D Part Submission Warrant PSWDocument1 pageMR23002 D Part Submission Warrant PSWRafik FafikNo ratings yet

- Quality Control Plan Static EquipmentDocument1 pageQuality Control Plan Static EquipmentdhasdjNo ratings yet

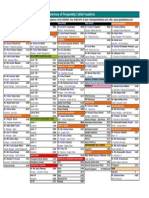

- Directory of Frequently Called Numbers: Maj. Sheikh RahmanDocument1 pageDirectory of Frequently Called Numbers: Maj. Sheikh RahmanEdward Ebb BonnoNo ratings yet

- FINALS REVIEWER ENVI ENGG Topic 1Document8 pagesFINALS REVIEWER ENVI ENGG Topic 1As ReNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Safari (A Short Story)Document20 pagesThe Ultimate Safari (A Short Story)David AlcasidNo ratings yet

- Poverty and Crime PDFDocument17 pagesPoverty and Crime PDFLudwigNo ratings yet

- Module A Specimen Questions January2020 PDFDocument5 pagesModule A Specimen Questions January2020 PDFShashi Bhusan SinghNo ratings yet

- PDS in Paschim MidnaporeDocument12 pagesPDS in Paschim Midnaporesupriyo9277No ratings yet

- 2024 - Chung 2024 Flexible Working and Gender Equality R2 CleanDocument123 pages2024 - Chung 2024 Flexible Working and Gender Equality R2 CleanmariaNo ratings yet

- Sarthak WorksheetDocument15 pagesSarthak Worksheetcyber forensicNo ratings yet

- Subaru Forester ManualsDocument636 pagesSubaru Forester ManualsMarko JakobovicNo ratings yet

- Switzerland: Food and CultureDocument18 pagesSwitzerland: Food and CultureAaron CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Business Startup Practical Plan PDFDocument70 pagesBusiness Startup Practical Plan PDFShaji Viswanathan. Mcom, MBA (U.K)No ratings yet

- Annex 8 Qualification of BalancesDocument11 pagesAnnex 8 Qualification of BalancesMassimiliano PorcelliNo ratings yet

- Investigating Population Growth SimulationDocument11 pagesInvestigating Population Growth Simulationapi-3823725640% (3)

- Hydrogeological Characterization of Karst Areas in NW VietnamDocument152 pagesHydrogeological Characterization of Karst Areas in NW VietnamCae Martins100% (1)

- fLOW CHART FOR WORKER'S ENTRYDocument2 pagesfLOW CHART FOR WORKER'S ENTRYshamshad ahamedNo ratings yet

- Hotel Housekeeping EQUIPMENTDocument3 pagesHotel Housekeeping EQUIPMENTsamahjaafNo ratings yet

- Simple Syrup I.PDocument38 pagesSimple Syrup I.PHimanshi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Executive Order 000Document2 pagesExecutive Order 000Randell ManjarresNo ratings yet

- Lease Practice QuestionsDocument4 pagesLease Practice QuestionsAbdul SamiNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Development & Competency in Juvenile JusticeDocument16 pagesAdolescent Development & Competency in Juvenile JusticeJudith KNo ratings yet

- Rudraksha - Scientific FactsDocument20 pagesRudraksha - Scientific FactsAkash Agarwal100% (3)

- IMCI Chart 2014 EditionDocument80 pagesIMCI Chart 2014 EditionHarold DiasanaNo ratings yet

- Funds Flow Statement ExplainedDocument76 pagesFunds Flow Statement Explainedthella deva prasad0% (1)

- OC - PlumberDocument6 pagesOC - Plumbertakuva03No ratings yet