Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ramos Garcia

Uploaded by

editorial.onlineOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ramos Garcia

Uploaded by

editorial.onlineCopyright:

Available Formats

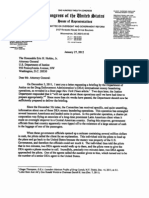

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 1 of 16

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA VS. EUDOXIO RAMOS-GARCIA

CASE NO.: H-11-833

MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO SUPRESS ORAL STATEMENTS OF DEFENDANT TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT: COMES NOW EUDOXIO RAMOS-GARCIA, Defendant, in the above-styled and numbered cause, and by his attorney of record, moves this Honorable Court to suppress all evidence resulting from an illegal arrest, illegal knock and talk illegal interrogation, illegal search, illegal seizure, and coerced oral statement given by the Defendant in Violation of the Fourth Amendment. I. All oral statements and information derived of the Defendant obtained as a result of the illegal statements taken from the Defendant. II. All testimony of any law-enforcement officers, their agents, and all other persons working in connection with such officers and agents, as to the alleged statements made by the Defendant. III. In support of this motion, the Defendant would show this Honorable Court that at the time of any conversations between the Defendant and any law-enforcement

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 2 of 16

offices, the Defendant was under an illegal arrest and deprived of his freedom by the attendant conduct of said law enforcement officers and the surrounding circumstances and that the actions of law enforcement rendered the taking of the statement in violation of defendants Fourth Amendment Rights and should be excluded under the Exclusionary Rule. IV. FACTUAL BASIS On Wednesday, October 26, 2011 US Marshalls received information from a confidential informant that JUAN MEJIA REYES was located at 600 River Point, Roma, Texas with high-powered rifles, handguns, and hand grenades. On that same day, US Marshalls set up surveillance on the home, but did not secure or attempt to secure a search warrant for the home or an arrest warrant for defendant. On October 27, 2011 US Marshalls, DEA, and US Border Patrol Agents set up surveillance at the residence and US Marshall Mejia then allegedly executed a knock and talk at approximately 2:00p.m. Law enforcement had no search warrants, no arrest warrants, no summons, no probable cause warrants, no probable cause to enter, no exigent circumstances, no citizens complaints, no indictments, or any other legal basis to enter the residence as the United States has stipulated. Testimony from US Marshall Bellino was that he saw Mrs. Garza and a male worker arrive shortly before agents entered the house and that he was in contact with other members of the raid team. Testimony from a disinterested third party, Mrs. Garza, was that she was never asked if she was the owner of the house, was never asked for permission to enter the house, but that when she heard

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 3 of 16

something outside, she looked out and saw civilians approaching the house with weapons drawn and weapons aimed at the door shouting everybody out, everybody out. She also testified the door was not closed but slightly open as a male worker was repairing the door frame. This testimony conflicts with US Marshall Mejias version that he knocked on the door and met with Mrs. Garza, asked her if she owned the house, to which she said yes, and then asked her if he could enter, to which she said yes. There was no evidence which corroborated US Marshall Mejias testimony that he either knocked or that he spoke to anyone at the entrance of the residence of defendant. At the very least, 7 US Marshalls, 1 DEA Agents, and 5 US Border Patrol Agents were part of the raid team who entered the house or had perimeter duties, and yet not one agent testified that he could see the front entrance to witness the knock, not one agent witnessed the questioning of Mrs. Garza, not one agent witnessed the actual entering of the house, and not one agent testified he was part of the initial raid team who entered the house with US Marshall Mejia. All the agents seemed to be in charge of perimeter duty. At some point agents entered the house without consent, without a search warrant, and without an arrest warrant for defendant. Testimony by a minor in the house was also consistent with Mrs. Garzas testimony that the door was slightly open and that a male worker was repairing the door frame. The minor testified that men entered with weapons drawn and weapons aimed with lights and that she ran upstairs, which is consistent with Mrs. Garzas testimony.

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 4 of 16

After US Marshall Mejia secured the first floor, agents yelled for occupants of the second floor to come down with their hands up. Defendant, his wife, and his three 11-year-old daughters then proceeded down the staircase with their hands raised and lazers from US Marshalls weapons on their chests. At 2:15pm upon stepping down on the last stair of the staircase, US Marshall Mejia tazered defendant on his back and handcuffed defendant while defendant was down. At this point, defendant was for all practical purposes under arrest without probable cause. Upon waking from the tazer, agents interrogated defendant. DEA Agent Adame then allegedly read defendant his Miranda rights. Again, no reports from DEA, US Marshalls, US Border Patrol or the US Attorneys Response to Defendants Motion to suppress documents this reading of Miranda rights at the house. After agents searched the house, no high-powered rifles, no handguns, no explosives, and no drugs were found. Agents then began to interrogate defendant and defendant made incriminating statements. At 6:40pm after four and a half hours of interrogation at the house, US Border Patrol Agents apprehended defendant, transported defendant to the US Border Patrol Station, and charged him with possession with intent to distribute marijuana. This charge conflicts with US Marshall Mejias report which falsely states defendant was arrested by DEA on a probable cause warrant for cocaine possession. At 7:50pm DEA Agents and US Border Patrol Agents Mirandized defendant and again, interrogation led to incriminating statements.

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 5 of 16

On October 28, 2011 at 2:15am US Border Patrol Agents Mirandized defendant in reference to his immigration status. Later on October 28, 2011 DEA Agents again Mirandized defendant and again, interrogation led to incriminating statements. On November 2, 2011 DEA Special Agent, MARK J. SCHMIDT filed a complaint alleging conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute 1,000 kilograms or more of a mixture and substance containing Marijuana, a Schedule I controlled substance along with a supporting probable cause affidavit against Defendant. Defendant was originally indicted in Cause No. M-11-1761 in the McAllen Division, but subsequently the indictment was dismissed on December 16, 2011. V. LAW APPLIED TO FACTUAL BASIS Suppression: When a defendant seeks to suppress evidence on the basis of a Fourth Amendment violation, defendant initially has the burden of proof. First, the defendant has to establish standing to contest the seizure. As the moving party defendant must produce evidence that defeats the presumption of proper police conduct and thereby shifts the burden of proof to the state. U.S. v. Thompson, 421 F.2d 373, 377 (5th Cir. 1970). A defendant meets his initial burden of proof by establishing that a search occurred without a warrant. Rogers v. U.S., 330 F.2d 535 (5th Cir. 1964). Defendant in this case clearly established standing by testimony of his daughter who stated the family was living in the home for a few days prior to October 27, 2011 and standing was further established through Mrs. Garzas testimony and evidence of a written contract to purchase the house. The Fourth Amendment: Search and Seizure: The Fourth Amendment to the United States

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 6 of 16

Constitution provides: The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. U.S. Const. Amend. IV. US Marshall Bellino testified he saw defendant in the back yard with his wife at this house the day before the raid and testimony from defendants daughter, and Mrs. Garza also testified the family was living in the house, thus establishing standing and an expectation of privacy of defendants house and person. Custody and Interrogation predicates must be present before a defendant is entitled to protection by the Fourth Amendment. Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 292, 300-02 (1980). A person is in custody only if: (1) he has been formally arrested or (2) a reasonable person would believe that his freedom of movement was restrained to the degree associated with a formal arrest. Stansberry v. California, 511 U.S. 318 (1994). Courts look at all the circumstances to conclude whether a reasonable person from defendants point of view would have believed he was under arrest. Thompson v. Keohane, 516 U.S. 99, 112 (1995). The term custodial interrogation is questioning by law enforcement officers after taking a person into custody or otherwise depriving him of his freedom in a significant way. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). Clearly, testimony shows defendant was tazered, fell to the floor, and was handcuffed at 2:18pm by agents. At this point any reasonable person would believe that his freedom of movement was restrained and several agents testified defendant was not free to go. The government may argue temporary detention for police officer safety, however, defendant was never told he was free to go, was not free to go, and the fact the government stipulated there was

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 7 of 16

no probable cause to arrest defendant and no probable cause existed to search the house makes this detention per se illegal and in violation of the Fourth Amendment as defendant was seized without probable cause, which is the cornerstone of an arrest. Interrogation is any speech or conduct by law enforcement concerning past criminal conduct that is reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response from the suspect. Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291, 300-01 (1980). Interrogation requires actual questioning of the suspect by an officer or an agent of law enforcement, but it does not include questions normally associated with procedures of arrest or custody, like booking questions. Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 496 U.S. 582 (1990). As to interrogation, Agents also testified defendant was questioned, but no agent seems to remember the specifics of the questioning which lead defendant to make incriminating statements. We know that US Border Patrol Agent Adame had the primary duty of establishing alienage during this custodial interrogation and that in response to questioning, defendant admitted to being in the country illegally. Clearly, agents elicited questions pertaining to defendants immigration status which resulted in an incriminating response. This response, defendants immigration status, is the governments only pretextual justification for arresting defendant, however, this pretextual justification is misguided and not the prevailing law in the United States Supreme Court or the United States Fifth Circuit. Attenuation of Taint: Federal Courts provide an exception to the exclusionary rule for evidence so tenuously related to the illegal act that illegality has become so attenuated as to dissipate the taint. Nardone v U.S., 308 U.S. 338, 341 (1939); Wong Sun v. U.S., 371 U.S. 471, 487-88 (1963). The prosecution has the burden of showing a sufficient break between the illegality and any confession obtained after that. Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200 (1979).

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 8 of 16

Merely giving Miranda warnings does not dissipate the taint of an illegal arrest to make a statement during a later detention admissible. Lanier v. South Carolina, 474 U.S. 25 (1985); Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1975). The prosecution must show not only that the statements meet the Fifth Amendment voluntariness standard, but also that the causal connection between the statements and the illegal arrest is broken sufficiently to purge the primary taint of the illegal arrest in light of the policies and interests of the Fourth Amendment. Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200 (1979). Clearly, the prosecution in defendants case did not bring any evidence before the Court that the causal connection between the statement and the illegal arrest was broken sufficiently to purge the primary taint of the illegal arrest in violation of the Fourth Amendment. The only testimony brought before the Court was testimony of defendant being Mirandized shortly after being tazered, but this testimony by DEA Agent Adame is not supported by any documented reports by DEA, US Marshalls, US Border Patrol, or is even mentioned in the governments response to defendants motion to suppress. Further, DEA Agent Adame is also the same agent who admitted under oath that he lies when he is not under oath. The Court should cautiously give his testimony the weight of a grain of salt. Even if the Court decides to give this agents testimony any credibility, Mirandizing defendant is a Fifth Amendment issue which cannot cure the Fourth Amendment violation. Warrantless Searches of the Home: Warrantless searches and seizures inside the home are presumptively unreasonable. Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573, 586 (1980). The physical entry of the home is the chief evil against which the wording of the Fourth Amendment is directed. Id. (quoting United States v. United States District Court, 407 U.S. 297, 313 (1972)). This Fourth Amendment protection is equally applicable to guests staying in hotel rooms and the

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 9 of 16

hotel management has no authority to consent to law enforcement entry into the room. Stoner v. California, 376 U.S. 483, 487-89 (1964). Overnight guests also have standing to challenge the search. Minnesota v. Olson, 495 U.S. 91 (1990). A particular location is subject to the warrant requirement if it involves a legitimate expectation of privacy. Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967). A warrantless search is per se unreasonable subject only to a few specifically established and well-delineated exceptions. Katz, 389 U.S. at 357. These exceptions are jealously and carefully drawn, and there must be a showing by those who seek exemption . . . that the exigencies of the situation made [the search] imperative . . . Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443, 455 (1971) (quoting Jones v. United States, 357 U.S. 493, 499 (1958)). In the absence of a warrant, the burden is on the government to show that the search falls within one of the exceptions. Vale v. Louisiana, 399 U.S. 30, 34 (1969). Since the government stipulated to the warrantless search and seizure, the seizure and search of defendants person and home were presumptively unreasonable. Further, the government did not bring any evidence to show that the search and seizure fell within one of the exceptions. In fact, US Marhsalls knew of the information from a reliable informant the day before the raid, early morning on Wednesday October 26, 2011, which stated high powered rifles, handguns, and explosives were at this house, however, no agent even considered going to a magistrate for a search warrant for the house or arrest warrant for defendant. Consent: Frequently the government will claim the defendant consented to the search. Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 219 (1973). The government has the burden of proving that consent was given freely and voluntarily. Bumper v. North Carolina, 391 U.S. 543, 548 (1968). Consent does not remove the taint of an illegal detention unless it is given voluntarily and it is an independent act of free will. Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 602-03

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 10 of 16

(1975); United States v. Chavez-Villarreal, 3 F.3d 124, 127 (5th Cir. 1993). A third person cannot consent to a search of anothers private possessions or space, United States v. Matlock, 415 U.S. 164 (1974), nor can the police disregard a persons refusal to consent even where a co-inhabitant has consented. Georgia v. Randolph, 547 U.S. 103 (2006). The police may rely on someones apparent authority if such reliance is objectively reasonable. Illinois v. Rodriguez, 497 U.S. 177 (1990). Under the Fourth Amendment, the government is required to prove by the preponderance of the evidence that a defendant gave voluntary and effective consent to search. The Court must also weigh the agents conduct in a knock-and-talk investigation. The purpose of a knock-and-talk investigation is to make investigatory inquiry, or, if officers reasonably suspect criminal activity, to gain the occupants consent to search. United States v. Gomez-Moreno, 479 F.3d 350 (5th Cir. 2007). The purposeis not to create a show of force, nor to make demands on occupants, nor to raid a residence. United States v. Gomez-Moreno, 479 F.3d 350 (5th Cir. 2007); United States v. Hernandez, (unpublished, 0940709, 5th Cir. 2010). When officers demand entry into a home without a warrant, they have gone beyond the reasonable knock and talk strategy of investigation. To have conducted a valid, reasonable knock and talk, the officers could have knocked on the front doorand waited a response; they might have knocked on the back doorWhen no one answered, the officers should have ended the knock and talk and changed their strategy by retreating cautiously, seeking a search warrant, or conducting further investigation. United States v. Gomez-Moreno, 479 F.3d 350 (5th Cir. 2007); United States v. Hernandez, (unpublished, 0940709, 5th Cir. 2010). On the issue of consent the Court heard conflicting testimony between a disinterested

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 11 of 16

third party, Mrs. Garza, and US Marshall Mejia. Mrs. Garza testified that agents entered the house without asking her any questions, without knocking, with weapons drawn, with weapons aimed, and yelling everyone out, everyone out. US Marshall Mejia stated that he asked Mrs. Garza if she was the owner of the house and if she would give him permission to enter the house to which both answers were yes. Although, the government may rely on the agents consent which was allegedly given by a third party, this reliance is flawed because testimony from US Marshall Bellino was that he saw Mrs. Garza arrive with a male worker shortly before agents entered the house, and that he was in contact with members of the raid team. Agents at this time knew Mrs. Garza and her worker were not occupants of the house, yet they allegedly asked her for permission to enter the house. Agents may rely on someones apparent authority if such reliance is objectively reasonable, however, agents knew Mrs. Garza was not living in the house as the house was under surveillance on the day of the raid and the day before and used this opportunity to circumvent the requirement of getting voluntary consent from defendant. Further, the fact that agents were coming to the door with weapons drawn and weapons aimed at the door does not indicate that consent was voluntary because of the show of police force. Mrs. Garza testified that she was terrified as she thought US Agents were from Mexico and believed she was going to die. This can only lead the Court to conclude that agents never identified themselves to Mrs. Garza, much less asked her if she was the owner or asked her for consent to enter the house. Warrantless Arrest In general, officers cannot make a warrantless arrest unless they have probable cause to believe the suspect has committed a felony offense, United States v. Watson, 423 U.S. 411 (1976). Probable cause exists where the known facts and circumstances are sufficient to

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 12 of 16

warrant a man of reasonable prudence in the belief that a crime was committed by the defendant or contraband is present. Ornelas v. United States, 517 U.S. 690, 695-96 (1996). The police may briefly detain an individual based on a reasonable articulable suspicion that he is committing a crime. Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968). Reasonable suspicion is based on the totality of the circumstances. United States v. Arvizu, 534 U.S. 266 (2002). An anonymous tip standing alone is not a sufficient basis for detention. Florida v. J.L., 529 U.S. 266 (2000). The government stipulated there was no probable cause to arrest defendant and no probable cause existed to search the house which makes this detention per se illegal and in violation of the Fourth Amendment as defendant was seized without probable cause and the government did not produce any evidence that agents believed defendant had committed a crime, or that contraband was present as nothing illegal was seized in the house. Exclusionary Rule: The Poisonous Tree: The Fourth Amendment bars the use of illegally seized evidence at trial. Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961); Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914). The exclusionary rule extends not only to the direct result of the unlawful search, but to its fruits as well. Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471(1963). Statements obtained during an unlawful detention must be suppressed. Davis v. Mississippi, 394 U.S. 721, 721 (1969); Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200, 216-19 (1979). Examples of circumstances which might indicate a seizure, even where the person did not attempt to leave, would be the threatening presence of several officers, the display of a weapon by an officer, some physical touching of the person of the citizen, or the use of language or tone of voice indicating that compliance with the officers request might be compelled. United States v. Mendenhall, 446 U.S. 544, 554 (1980). In defendants case at the very least, 7 US Marshalls, 1 DEA Agent, and 5 US

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 13 of 16

Border Patrol Agents were part of the raid team who entered the house yelling with weapons drawn, weapons aimed at his three 11 year old girls, weapons aimed at his wife, weapons aimed at him, while all of his family complied with officers yelling and walked down the stairs with their hands in the air, as he was ultimately tazered and handcuffed. Surely these circumstances would indicate that compliance with an officers request might be compelled. This case is similar to Dunaway v. New York, 422 U.S. 200 (1979), in which the Supreme Court excluded a post-Miranda confession because the police illegally seized the defendant without probable cause almost immediately before the statement was made. Id. 202-07. The Court determined that seizing Dunaway and taking him to the police station for questioning without probable cause was a Fourth Amendment violation, and deemed it necessary to determine whether the connection between the constitutional violation and the incriminating statement was sufficiently attenuated to warrant its admission. Dunaway v. New York, 422 U.S. 200 (1979); United States v. Hernandez, (unpublished, 11-40201, 5th Cir. 2012). Based on the fact that Dunaway was admittedly seized without probable cause in the hope that something might turn up, and confessed without an intervening event of significanc, the Court determined that the confession must be excluded. Dunaway v. New York, 422 U.S. 200 (1979); United States v. Hernandez, (unpublished, 11-40201, 5th Cir. 2012) Defendant as in Dunaway was admittedly seized without probable cause in the hope that something might turn up, and confessed without any intervening event of significance. The lack of probable cause for a warrant or search warrant seems to be the repeated factor of excluding illegally seized evidence. Intervening events of significance include for example, an appearance before a

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 14 of 16

magistrate or consultation with an attorney. Johnson v. Louisianna, 406 U.S. 356, 365 (1972) (holding that the taint of an allegedly illegal arrest was purged when defendant was represented by counsel and brought before a magistrate before the incriminating lineup occurred.) Merely questioning a suspect in insufficient to constitute an intervening event of significance. Brown, 422 U.S. at 602-05. The government did not bring any evidence to the Court which showed an intervening event of significance to demonstrate to the Court that the connection between the constitutional violation and defendants incriminating statements were sufficiently attenuated to warrant their admission. Even a Miranda waiver will not attenuate the taint of an unconstitutional detention unless intervening events break the connection between the illegal detention and the confession. Dunaway, 442 U.S. at 218-19. Statements:The government must satisfy the court that the defendants statements were obtained after a knowing and voluntary waiver of his constitutional rights. Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964); Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938). If the interrogation has occurred without the presence of an attorney, the government bears a heavy burden in demonstrating that the defendant knowingly and intelligently waived his rights. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 47475 (1966). V. Defendant asks this Honorable Court to apply the Exclusionary Rule protection under the Fourth Amendment as any oral statements as well as any evidence or testimony developed as a result of the oral statements were tainted by the illegal and unlawful detention or arrest of the Defendant herein, in violation of the Defendants

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 15 of 16

constitutional rights under the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and Art-I 9 of the Texas Constitution. Any statement given by the Defendant was not voluntary. WHEREFORE, PREMISES CONSIDERED, Defendant respectfully prays that this Honorable Court consider the evidence, testimony, and this memorandum of law on defendants pre-trial motion, and after having heard the evidence, that this Honorable Court order any and all confessions, admissions, and oral statements taken from the Defendant by law-enforcement officers as well as any evidence or testimony developed as a result of said illegal statements or confessions be suppressed for the aforementioned reasons or any other reasons this Honorable Court deems necessary under the law. Respectfully submitted, By: /s/Baltazar Salazar BALTAZAR SALAZAR State Bar No. 00791590 Federal I.D.: 18536 (713)655-1300

CERTIFICATE OF CONFERENCE This is to certify that counsel for the Defendant has consulted with the Assistant United States Attorney assigned to this case in an attempt to obtain the above requested relief, and Assistant U.S. Attorney:

Case 4:11-cr-00833 Document 35

Filed in TXSD on 02/26/12 Page 16 of 16

is not opposed; or X is opposed. /s/Baltazar Salazar BALTAZAR SALAZAR

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Baltazar Salazar, hereby certify that on this the 26th day of February, 2012 a true and correct copy of the foregoing Memorandum of Law in Support of Defendants Motion to Suppress Oral Statements was forwarded to: Mr. Richard D. Hanes Assistant U.S. Attorney P.O. Box 61129 Houston, Texas 77208-1129 Electronic Mail /s/Baltazar Salazar BALTAZAR SALAZAR

You might also like

- D. Applicant-Owned: GREEN 7 - Manulearn MOCK ExamDocument23 pagesD. Applicant-Owned: GREEN 7 - Manulearn MOCK ExamAlron Dela Victoria AncogNo ratings yet

- Cuyugan vs. Santos deed of sale intentionDocument2 pagesCuyugan vs. Santos deed of sale intentionkitakatttNo ratings yet

- ATF Approved The SB Tactical SOB and SBM4 in 2017Document10 pagesATF Approved The SB Tactical SOB and SBM4 in 2017AmmoLand Shooting Sports News100% (1)

- Novozhilov Yappa Electrodynamics PDFDocument362 pagesNovozhilov Yappa Electrodynamics PDFAscanio Barbosa100% (1)

- Code-of-Conduct For Construction IndustryDocument12 pagesCode-of-Conduct For Construction IndustryBhawna RighteousNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument23 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PublishedDocument92 pagesPublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia, 459 F.3d 1059, 10th Cir. (2006)Document18 pagesUnited States v. Garcia, 459 F.3d 1059, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Torres-Castro, 10th Cir. (2006)Document18 pagesUnited States v. Torres-Castro, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Ana Julia Correa-Tobon, 748 F.2d 1509, 11th Cir. (1984)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Ana Julia Correa-Tobon, 748 F.2d 1509, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ian Lightbourne v. Richard L. Dugger, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections, Robert A. Butterworth, Attorney General, 829 F.2d 1012, 11th Cir. (1987)Document34 pagesIan Lightbourne v. Richard L. Dugger, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections, Robert A. Butterworth, Attorney General, 829 F.2d 1012, 11th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument36 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Carloss, 10th Cir. (2016)Document57 pagesUnited States v. Carloss, 10th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberts, 4th Cir. (1998)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Roberts, 4th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Steve Ward, Individually and as Father and Next Friend of Tara Ward and Casey Ward, and Dawn Appenzeller, Individually and as Mother and Next Friend of Adam Appenzeller v. United States Customs Service, Twelve Unknown Agents, 17 F.3d 317, 10th Cir. (1994)Document7 pagesSteve Ward, Individually and as Father and Next Friend of Tara Ward and Casey Ward, and Dawn Appenzeller, Individually and as Mother and Next Friend of Adam Appenzeller v. United States Customs Service, Twelve Unknown Agents, 17 F.3d 317, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Louis Lopez, JR., United States of America v. Hernan Navarro, United States of America v. Juan Crispin, United States of America v. Delroy Josiah, 271 F.3d 472, 3rd Cir. (2001)Document21 pagesUnited States v. Louis Lopez, JR., United States of America v. Hernan Navarro, United States of America v. Juan Crispin, United States of America v. Delroy Josiah, 271 F.3d 472, 3rd Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Thomas, 372 F.3d 1173, 10th Cir. (2004)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Thomas, 372 F.3d 1173, 10th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument29 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bliss v. Franco, 446 F.3d 1036, 10th Cir. (2006)Document19 pagesBliss v. Franco, 446 F.3d 1036, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Miguel Marcelo Retolaza, 398 F.2d 235, 4th Cir. (1968)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Miguel Marcelo Retolaza, 398 F.2d 235, 4th Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Aponte-Matos v. Toledo-Davila, 135 F.3d 182, 1st Cir. (1998)Document14 pagesAponte-Matos v. Toledo-Davila, 135 F.3d 182, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Freeman ICE Child Porn Case With Improper Search and Seizure Dismissed OregonDocument24 pagesFreeman ICE Child Porn Case With Improper Search and Seizure Dismissed Oregonmary engNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 80, Docket 28232Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 80, Docket 28232Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Campa, 234 F.3d 733, 1st Cir. (2000)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Campa, 234 F.3d 733, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Alberto Llanes, 398 F.2d 880, 2d Cir. (1968)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Alberto Llanes, 398 F.2d 880, 2d Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument4 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Davis, 1st Cir. (2014)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Davis, 1st Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberto Salgado, 347 F.2d 216, 2d Cir. (1965)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Roberto Salgado, 347 F.2d 216, 2d Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. William Columbus Smith, A/K/A Smitty, 995 F.2d 1064, 4th Cir. (1993)Document6 pagesUnited States v. William Columbus Smith, A/K/A Smitty, 995 F.2d 1064, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PrecedentialDocument35 pagesPrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument25 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Manuel Pedro, A/K/A Manuel Condiles, 999 F.2d 497, 11th Cir. (1993)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Manuel Pedro, A/K/A Manuel Condiles, 999 F.2d 497, 11th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jose A. Gonzalez, 719 F.2d 1516, 11th Cir. (1983)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Jose A. Gonzalez, 719 F.2d 1516, 11th Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument12 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Barbara Rodriguez, 706 F.2d 31, 2d Cir. (1983)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Barbara Rodriguez, 706 F.2d 31, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Young, 10th Cir. (2008)Document14 pagesUnited States v. Young, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UNITED STATES of America v. Ronnie PEPPERS, AppellantDocument25 pagesUNITED STATES of America v. Ronnie PEPPERS, AppellantScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- State V JeffersonDocument23 pagesState V JeffersonBenjamin KelsenNo ratings yet

- Precedential: JudgesDocument21 pagesPrecedential: JudgesScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Marquez-Madrid, 10th Cir. (2007)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Marquez-Madrid, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Marshall, 10th Cir. (1998)Document12 pagesUnited States v. Marshall, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Augustine Ferrone, 438 F.2d 381, 3rd Cir. (1971)Document13 pagesUnited States v. Augustine Ferrone, 438 F.2d 381, 3rd Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- David Glen Jordan v. United States, 348 F.2d 433, 10th Cir. (1965)Document5 pagesDavid Glen Jordan v. United States, 348 F.2d 433, 10th Cir. (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- State's Motion To Dismiss Charles Flores' Application For Writ of Habeas CorpusDocument74 pagesState's Motion To Dismiss Charles Flores' Application For Writ of Habeas CorpusThisIsFusionNo ratings yet

- United States v. Marie Theresa Haala, 532 F.2d 1324, 10th Cir. (1976)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Marie Theresa Haala, 532 F.2d 1324, 10th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Fox, 600 F.3d 1253, 10th Cir. (2010)Document19 pagesUnited States v. Fox, 600 F.3d 1253, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. James Fields Christopher Crawley, 113 F.3d 313, 2d Cir. (1997)Document16 pagesUnited States v. James Fields Christopher Crawley, 113 F.3d 313, 2d Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Michael Anthony Brissette, United States of America v. Kentley H. Thomas, A/K/A Thomas Kentley, 14 F.3d 597, 4th Cir. (1993)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Michael Anthony Brissette, United States of America v. Kentley H. Thomas, A/K/A Thomas Kentley, 14 F.3d 597, 4th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Lopez, 372 F.3d 1207, 10th Cir. (2004)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Lopez, 372 F.3d 1207, 10th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Lopez-Ochoa, 10th Cir. (2004)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Lopez-Ochoa, 10th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. PuffDocument22 pagesUnited States v. PuffScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Winston, 444 F.3d 115, 1st Cir. (2006)Document16 pagesUnited States v. Winston, 444 F.3d 115, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jose M. Castillo, A/K/A Richard Lara, A/K/A Daniel, 287 F.3d 21, 1st Cir. (2002)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Jose M. Castillo, A/K/A Richard Lara, A/K/A Daniel, 287 F.3d 21, 1st Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Motion To Suppress Confession ExampleDocument9 pagesMotion To Suppress Confession ExamplejobohoNo ratings yet

- United States v. Wallace Frank, 901 F.2d 846, 10th Cir. (1990)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Wallace Frank, 901 F.2d 846, 10th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Melchor Tafoya, JR., 459 F.2d 424, 10th Cir. (1972)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Melchor Tafoya, JR., 459 F.2d 424, 10th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Raymond Edward Davis, JR., 313 F.3d 1300, 11th Cir. (2002)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Raymond Edward Davis, JR., 313 F.3d 1300, 11th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. J. Paul Joines and John Robert Joines. Appeal of John Robert Joines, 246 F.2d 278, 3rd Cir. (1957)Document2 pagesUnited States v. J. Paul Joines and John Robert Joines. Appeal of John Robert Joines, 246 F.2d 278, 3rd Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. James Williams, 612 F.2d 735, 3rd Cir. (1980)Document7 pagesUnited States v. James Williams, 612 F.2d 735, 3rd Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mary Velardi and Frances Velardi v. Cornelius R. Walsh, Jr. and Robert L. Boek, 40 F.3d 569, 2d Cir. (1994)Document10 pagesMary Velardi and Frances Velardi v. Cornelius R. Walsh, Jr. and Robert L. Boek, 40 F.3d 569, 2d Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Eugenia Gonzalez, 835 F.2d 449, 2d Cir. (1987)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Eugenia Gonzalez, 835 F.2d 449, 2d Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument25 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Harris, 10th Cir. (2007)Document18 pagesUnited States v. Harris, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Victor Manuel Torres-Castro, 470 F.3d 992, 10th Cir. (2006)Document11 pagesUnited States v. Victor Manuel Torres-Castro, 470 F.3d 992, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Houston (02.18.13) PDFDocument2 pagesHouston (02.18.13) PDFeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Response Filed by Marshall David Brown JRDocument10 pagesResponse Filed by Marshall David Brown JRHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Julian Zapata Espinoza - Statement of FactsDocument12 pagesJulian Zapata Espinoza - Statement of Factseditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Parking Locations Map Media Friendly 03.01.2013 FINALDocument1 pageParking Locations Map Media Friendly 03.01.2013 FINALeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Hobby Master PlanDocument5 pagesHobby Master Planeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Arizona v. United StatesDocument76 pagesArizona v. United StatesDoug MataconisNo ratings yet

- Shooting Timeline 19p CDocument1 pageShooting Timeline 19p Ceditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Hospital Ratings 59p CDocument1 pageHospital Ratings 59p CdanajthomNo ratings yet

- Chron Front PageDocument1 pageChron Front Pageeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Heil ComplaintDocument1 pageHeil Complainteditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Hans ComplaintDocument4 pagesHans Complainteditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Dangerous Wild Animal RegulationsDocument18 pagesDangerous Wild Animal Regulationseditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Secretary Sebelius Letter To The Governors 071012Document3 pagesSecretary Sebelius Letter To The Governors 071012editorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Miller v. AlabamaDocument62 pagesMiller v. AlabamaDoug MataconisNo ratings yet

- MGB and 3rd Parties Motion For Sanctions W Fax Conf To RHDocument7 pagesMGB and 3rd Parties Motion For Sanctions W Fax Conf To RHeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Reply To Response To Motion For SanctionsDocument12 pagesReply To Response To Motion For SanctionsHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Allen Stanford Accuses Receiver and Baker Botts Attorney Kevin Sadler of Criminal ConductDocument14 pagesAllen Stanford Accuses Receiver and Baker Botts Attorney Kevin Sadler of Criminal ConductStanford Victims Coalition100% (1)

- TX Letter 3.15.12Document2 pagesTX Letter 3.15.12editorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- 1 3Document2 pages1 3editorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Allen Stanford Accuses Receiver and Baker Botts Attorney Kevin Sadler of Criminal ConductDocument14 pagesAllen Stanford Accuses Receiver and Baker Botts Attorney Kevin Sadler of Criminal ConductStanford Victims Coalition100% (1)

- March 1 RequestDocument21 pagesMarch 1 Requesteditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- 1 4Document8 pages1 4editorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- 1 MainDocument14 pages1 Maineditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Webb WebbDocument3 pagesWebb Webbeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Steve Jobs FBIDocument191 pagesSteve Jobs FBIJay Yarow100% (1)

- ATFTraffickingDocument2 pagesATFTraffickingeditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- De La Cruz Reyna ObjectionDocument4 pagesDe La Cruz Reyna Objectioneditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Issa Letter To Holder IDocument2 pagesIssa Letter To Holder Ieditorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Issa Letter 2Document2 pagesIssa Letter 2editorial.onlineNo ratings yet

- Tax Advisor July 2017Document68 pagesTax Advisor July 2017John RockefellerNo ratings yet

- PSC Graduate Trainee PolicyDocument9 pagesPSC Graduate Trainee PolicyManoa Nagatalevu TupouNo ratings yet

- Bars of LimitationDocument27 pagesBars of LimitationhargunNo ratings yet

- The Limitation Act, 1908 PDFDocument92 pagesThe Limitation Act, 1908 PDFMimi mekiNo ratings yet

- Warrantless SearchesDocument515 pagesWarrantless SearchesChristine Joy AbrogueñaNo ratings yet

- TaimurazDocument7 pagesTaimurazBrianne DyerNo ratings yet

- Summary Reyes Book Art 11-13Document7 pagesSummary Reyes Book Art 11-13Michaella ReyesNo ratings yet

- Registered Unregistered Land EssayDocument3 pagesRegistered Unregistered Land Essayzamrank91No ratings yet

- Real Estate BrokerageDocument135 pagesReal Estate Brokerageخالد العبيدي100% (1)

- BAYAN MUNA V. ROMULO G.R. No. 159618Document21 pagesBAYAN MUNA V. ROMULO G.R. No. 159618salemNo ratings yet

- Tropical ManualDocument20 pagesTropical Manualjenm1228No ratings yet

- Local Government Notes PDFDocument115 pagesLocal Government Notes PDFMysh PD100% (1)

- Labor Relations (Strike)Document472 pagesLabor Relations (Strike)Au Milag BadanaNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Change of Name CaseDocument2 pagesChange of Name CaseMirabel Sanchria Kalaw OrtizNo ratings yet

- Grey Alba de La Cruz, GR 5246, Sept. 16, 1910, 17 Phil. 49Document3 pagesGrey Alba de La Cruz, GR 5246, Sept. 16, 1910, 17 Phil. 49Bibi JumpolNo ratings yet

- Sociology Final Draft - PrakharDocument9 pagesSociology Final Draft - Prakharchetan vermaNo ratings yet

- PV ManualDocument102 pagesPV ManualLind D. QuiNo ratings yet

- 4.1 Understanding Organization and Its Context: Internal Issues Context of The Organization External IssuesDocument6 pages4.1 Understanding Organization and Its Context: Internal Issues Context of The Organization External IssuesShaimaa AbdelsalamNo ratings yet

- Borchi Gol 0011 MsdsDocument7 pagesBorchi Gol 0011 MsdsŞükrü TaşyürekNo ratings yet

- 02-PBC v. Lui She, 21 SCRA 52 (1967) - Escra PDFDocument22 pages02-PBC v. Lui She, 21 SCRA 52 (1967) - Escra PDFJNo ratings yet

- Prevent corporate name confusion with SEC approvalDocument2 pagesPrevent corporate name confusion with SEC approvalAleli BucuNo ratings yet

- Frailes y Clerigos RetanaDocument149 pagesFrailes y Clerigos RetanaSanja StosicNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet 60 - Edition 7 - Aug 2013 PDFDocument28 pagesPamphlet 60 - Edition 7 - Aug 2013 PDFmonitorsamsungNo ratings yet

- Case Digest in LTDDocument37 pagesCase Digest in LTDNica09_foreverNo ratings yet