Professional Documents

Culture Documents

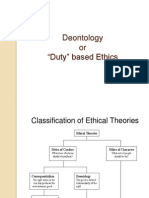

Deontology

Uploaded by

Ryan AbuyenOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Deontology

Uploaded by

Ryan AbuyenCopyright:

Available Formats

A2 Religious Studies: Developments (Paper 3): Ethics.

Deontology

A deontologist is someone who believes that there are certain types of acts that are wrong in themselves and that we have a duty not to do those types of acts. Someone who follows either Kantian ethics or Natural Moral law would be a deontologist. The word deontology comes from the Greek deon, meaning duty. Deontologists contrast with teleologists, or consequentialists, who judge the goodness of an action by looking at the consequences that the action brings about. Utilitarians and situation ethicists are teleologists. C. Fried has described deontology as follows: The goodness of the ultimate consequences does not guarantee the rightness of the actions which produced them. The two realms are not only distinct for the deontologist, but the right is prior to the good. Nancy-Ann Davis points out that deontological statements have three qualities to them:

1. They are negatively formulated. In other words, they are written in

the form do not e.g. do not lie rather than the positive version which would be always tell the truth. This means that anything that lies outside the boundary of the prohibition e.g. holding back information instead of lying, is permitted. 2. They are narrowly framed and bounded i.e. they refer to very specific actions e.g. do not lie. 3. They are narrowly directed i.e. they are directed at the agents actions, rather than at the consequences of that action. For example, we only violate the deontological prohibition against harming another if we intentionally harm another. The prohibition is not violated if harm is an unintended consequence of our action e.g. if we open cages of lions to set them free from the cruelty of a circus and they then go on a killing spree. This third quality distinguishes between acts and omissions. For the deontologist, it is wrong to act if that action breaks a rule. However, if you fail to act and the consequence of failing to act does harm, you have not done anything wrong. This is called an omission. James Rachels argues that there is no meaningful distinction between acts and omissions: he argues that if you fail to act knowing that your action will lead to bad consequences, morally, this is as bad as acting. He gives the example of Smith, who stands to inherit a lot of money if his six year-old cousin dies. One evening, the child is having a bath and Smith drowns him. Compare this with Jones, who similarly stands to gain from his cousins death. He goes up to the bathroom to drown the boy, but as he gets there, the boy slips and hits his head and falls under the water and drowns. Jones could have acted to save him. For the deontologist, Jones has done nothing wrong and Rachels criticises this. The deontologist believes in a priori moral statements. In other words, the deontologist would use something like reason, or religious revelation to decide upon their moral principles before finding themselves in a situation that requires moral decision making. As Nancy-Ann Davis writes:

A2 Religious Studies: Developments (Paper 3): Ethics.

To act rightly, agents must first of all refrain from acts that can be said and known to be, before the fact, wrong. So what are these before the fact wrongs? Thomas Nagel suggests the following: Common moral intuition recognizes several types of deontological reasons limits on what one may do to people or how one may treat them. There are special obligations created by promises and agreements; the restrictions against lying and betrayal; the prohibitions against violating various individual rights, rights not to be killed, injured, imprisoned, threatened, tortured, coerced, robbed; the restrictions against imposing certain sacrifices on someone simply as a means to an end; and perhaps the special claim of immediacy, which makes distress at a distance so different from distress in the same room. There may also be a deontological requirement of fairness, of even-handedness or equality in ones treatment of people. How do deontologists arrive at these truths? Some may appeal to common moral intuitions: the its just wrong argument. Others may appeal to a religious tradition. The Bible sets down a long list of moral rules revealed by God: the 613 mitzvot or commandments, many of which are to be found in the books of Deuteronomy or Leviticus. There are others who appeal to reason. Immanuel Kant devised a deontological ethic based purely on the use of reason to discern actions that we have a duty to perform and devised the Categorical Imperative to enable us to decide what our duties are. Those who follow the Natural Law tradition devised by Cicero and Aquinas argue that there are moral facts which we must use our reason to discover and that it is our duty to act in accordance with those moral facts. Alongside having a priori moral truths, deontologists are not allowed to consider the consequences of their actions, even if the consequences of a particular action bring about more harm than the act itself. By the deontologists lights, it is not the badness of the consequences of a particular lie, or of lying in general that makes it wrong to lie; rather, lies are wrong because of the sorts of things they are, and are thus wrong even when they produce foreseeably good consequences.1 Deontological ethics is not impartial. Consequentialist ethics, when faced with the dilemma of killing one person to save the lives of five, must weigh each of the people equally and would conclude that it is good to kill the one person. Deontology however, because it tells us that we have a duty not to kill, gives more value to the life of the one person against the lives of the five that would die as a result of our action (such as in the famous example of Jim and the Indians from Bernard Williams.) Also, the deontologist tells us that our own avoidance of wrongdoing is more important than intervening to stop others from doing wrong. Again, Davis writes:

Nancy-Ann Davis in A Companion to Ethics, Singer (ed) p206-7.

A2 Religious Studies: Developments (Paper 3): Ethics.

the preservation of our own virtue outweighs not only the preservation of others lives, it also outweighs the preservation of others virtue. We may not save a life with a lie even when the lie would prevent the loss of life by deceiving an evil agent who credibly intends to kill several innocent victims.2 Deontologists also believe in something that Thomas Nagel calls the traditional principle of double effect. He defines it as follows: to violate deontological constraints, one must maltreat someone else intentionally. The maltreatment must be something that one does or chooses, either as an end or as a means, rather than something ones actions merely cause or fail to prevent but that one does not aim at. A good example of this is the case of Gianna Beretta Molla. In April 1962, she was pregnant with her fourth child. However, she developed a cancer in her uterus. The only way to save the life of the Gianna, would have been to remove the uterus containing the foetus; thus performing an unintended abortion. Under double-effect, this would have been permitted. On April 21st 1962, Gianna gave birth to her daughter. Gianna died on the 28th April. Read more about her at:

http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20040516_berettamolla_en.html

One of the great strengths of deontology, is that it seems to fit in with an intuition that we all have, that certain things are just wrong and that we must not do them. Louis Pojman gives the example of torturing innocent children; we just know that this is wrong. A society that is based upon such deontological rules would be able to absolutely outlaw certain immoral actions. Also, deontologists avoid the problem of trying to predict the consequences of their actions. Utilitarians for example have to decide what the consequences of all their actions are and whether or not they increase the amount of pleasure in the world. This is the no-rest objection i.e. that utilitarians are always having to consider how much pleasure their actions promote. The deontologist has no such problem: so long as their actions do not violate a prohibition, they can do what they like. Davis has called this having moral breathing room. However, deontological ethics does have some very serious drawbacks. One of the principal weaknesses, is that of conflicting moral duties. If one finds oneself in a situation where two or more moral duties come into conflict, how does one decide between the two? One solution is the so called ethic of prima facie duties devised by Jonathan Dancy, which is very similar to Bernard Hooses Proportionalism. He suggests that in situations where two duties come into conflict, we simply decide which duty is the more pressing and follow that one.

Ibid p207.

A2 Religious Studies: Developments (Paper 3): Ethics.

The other criticism of deontology, is that it reduces morality to the simple avoidance of bad actions, rather than making an effort to develop a moral character like Virtue Ethics. Surely, it is better for somebody to choose to perform a good action, rather than act to avoid certain things they believe to be bad? Nancy Davis writes: we are members of a moral community, not just discrete rational wills or guardians of our own virtue, and we care about other individuals in that community, as well as about the community itself. And the proper expression of that concern is not just the credo of non-interference that gets reflected in the minimal deontological notion of respect, and the narrow deontological constraints that are taken to express or follow from it (for example, not lying, not cheating, or otherwise impeding people from getting on with their own lives), but one that involves, and requires, peoples active interest in promoting others well-being.

You might also like

- Deontological ethics explainedDocument6 pagesDeontological ethics explainedPAULBONANo ratings yet

- EthicsDocument4 pagesEthicsDhaval MistryNo ratings yet

- Module 1 AssignmentDocument4 pagesModule 1 AssignmentWinston QuilatonNo ratings yet

- Duty-Based Ethics ExplainedDocument4 pagesDuty-Based Ethics ExplainedafiNo ratings yet

- Final DeontologyDocument31 pagesFinal DeontologyRoshni BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Ethical TeachingDocument55 pagesEthical TeachingJesús Goenaga PeñaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Lecture2Document11 pagesEthics Lecture2keithquinto27No ratings yet

- Duty EthicsDocument6 pagesDuty EthicsJamaica DUMADAGNo ratings yet

- DeontologyDocument3 pagesDeontologyGalito GuañunaNo ratings yet

- DeontologyDocument8 pagesDeontologyEphremZelekeNo ratings yet

- Logic NotesDocument33 pagesLogic NotesCharles LaspiñasNo ratings yet

- ERIC JOHN R NEMI-PA214 (Deontology)Document5 pagesERIC JOHN R NEMI-PA214 (Deontology)Nemz KiNo ratings yet

- Ethical FallaciesDocument5 pagesEthical Fallaciesst3792No ratings yet

- THEORIES OF ETHICS AND MORALITYDocument42 pagesTHEORIES OF ETHICS AND MORALITYYash HoraNo ratings yet

- LAWDocument6 pagesLAWWayland DepidepNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Types of Ethical ThoughtsDocument55 pagesModule 3 Types of Ethical ThoughtsKathleen AngNo ratings yet

- Types of Ethical ThoughtsDocument55 pagesTypes of Ethical ThoughtsKeana DacayanaNo ratings yet

- Comparing Utilitarianism and Deontological EthicsDocument12 pagesComparing Utilitarianism and Deontological EthicsJustin ViberNo ratings yet

- Bioethics Midterm 1Document82 pagesBioethics Midterm 1Pasay Trisha Faye Y.No ratings yet

- Paper 5 - Making The Right DecisionDocument15 pagesPaper 5 - Making The Right DecisionchitocsuNo ratings yet

- Gec09 PPT3Document69 pagesGec09 PPT3Abigail CaagbayNo ratings yet

- DeonthologyDocument4 pagesDeonthologyEric LaurioNo ratings yet

- Ulitarian or or Consequentialist Ethics Utilitarianism (Also Called Consequentialism) Is A Moral Theory Developed and Refined in TheDocument2 pagesUlitarian or or Consequentialist Ethics Utilitarianism (Also Called Consequentialism) Is A Moral Theory Developed and Refined in TheAnonymous sQPULpNo ratings yet

- 10major Theories in Normative EthicsDocument5 pages10major Theories in Normative EthicsMargaux Anne BarbinNo ratings yet

- Ivs Be Unit III Handouts 2016Document17 pagesIvs Be Unit III Handouts 2016Gaurang singhNo ratings yet

- Class Notes For Philosophy 251Document3 pagesClass Notes For Philosophy 251watah taNo ratings yet

- Cognitivism vs Non-Cognitivism ReactionDocument7 pagesCognitivism vs Non-Cognitivism ReactioncelineymeNo ratings yet

- Moral Accountability Lesson 3 Determinant of Morality Lesson V Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesMoral Accountability Lesson 3 Determinant of Morality Lesson V Reflection PaperAleeza RaineNo ratings yet

- Group 14 - EECV - Mid Term AssignmentDocument16 pagesGroup 14 - EECV - Mid Term AssignmentShikha BisenNo ratings yet

- Module On Theories of CrimeDocument21 pagesModule On Theories of CrimeLizel Joy AcobNo ratings yet

- Moral Realism and Dilemmas ExplainedDocument7 pagesMoral Realism and Dilemmas ExplainedMaurille Tezon ArrabisNo ratings yet

- Major Ethical Theories ExplainedDocument4 pagesMajor Ethical Theories ExplainedAd NanNo ratings yet

- WK 3 4 Secularists 1Document7 pagesWK 3 4 Secularists 1cherry blossomsNo ratings yet

- Deontological EthicsDocument8 pagesDeontological EthicsDarwin Agustin LomibaoNo ratings yet

- Virtue EthicsDocument8 pagesVirtue Ethicsjescy pauloNo ratings yet

- Thesis of Soft DeterminismDocument8 pagesThesis of Soft DeterminismElizabeth Williams100% (2)

- MoralagentdoxDocument12 pagesMoralagentdoxMirafelNo ratings yet

- The Idea of Justice and The Use of Torture A Moral Dilemma Between The Utilitarian Ideology and The Deontologist Ideology.Document7 pagesThe Idea of Justice and The Use of Torture A Moral Dilemma Between The Utilitarian Ideology and The Deontologist Ideology.dylanameziane25No ratings yet

- WEEK 1: ETHICS DEFINEDDocument4 pagesWEEK 1: ETHICS DEFINEDTimo ThsNo ratings yet

- Philosophies - Civil Disobedience Concept - Novemeber 2021Document19 pagesPhilosophies - Civil Disobedience Concept - Novemeber 2021Khoa NguyenNo ratings yet

- Chapter I - Understanding Morality and Moral StandardsDocument30 pagesChapter I - Understanding Morality and Moral StandardsDaphny Asong100% (2)

- New Cullings for Normative EthicsDocument13 pagesNew Cullings for Normative EthicsShekhar TripathiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document12 pagesChapter 2Revy CumahigNo ratings yet

- NotesDocument149 pagesNotesMatt Yicheng SongNo ratings yet

- Module 1-17 Good Governance and Social ResponsibilityDocument81 pagesModule 1-17 Good Governance and Social ResponsibilitymaiseNo ratings yet

- Phil FinalDocument4 pagesPhil Finalapi-253711979No ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument22 pagesEnvironmental EthicsParth ShettiwarNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Ethical Obligations and Decision Making in Accounting Text and Cases 5th by MintzDocument21 pagesSolution Manual For Ethical Obligations and Decision Making in Accounting Text and Cases 5th by MintzCory Smith100% (38)

- Duty Ethics ExplainedDocument11 pagesDuty Ethics ExplainedJelimae LantacaNo ratings yet

- Hi Guys Its Done Hahahahah121Document6 pagesHi Guys Its Done Hahahahah121Jose Mariano MelendezNo ratings yet

- PHILOSOPHYDocument30 pagesPHILOSOPHYPrincess Mae AlejandrinoNo ratings yet

- Moral Relativism: An AntidoteDocument12 pagesMoral Relativism: An AntidoteGil Sanders100% (1)

- p-4-8r Exploring EthicsDocument9 pagesp-4-8r Exploring Ethicsapi-552175678No ratings yet

- BS2B-Deontology, Teleology and UtilitarianismDocument2 pagesBS2B-Deontology, Teleology and UtilitarianismRoshin TejeroNo ratings yet

- Ethics: Understanding Moral Dilemmas and Types of Ethical ConflictsDocument8 pagesEthics: Understanding Moral Dilemmas and Types of Ethical ConflictsRaven Jay MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Essay On Freedom and DeterminismDocument3 pagesEssay On Freedom and DeterminismWill Harrison100% (3)

- Moving Beyond Good and Evil: A Theory of Morality, Law, and GovernmentFrom EverandMoving Beyond Good and Evil: A Theory of Morality, Law, and GovernmentNo ratings yet

- Positive Harmlessness in Practice: Enough for Us All, Volume TwoFrom EverandPositive Harmlessness in Practice: Enough for Us All, Volume TwoNo ratings yet

- Moral Minds: The Nature of Right and WrongFrom EverandMoral Minds: The Nature of Right and WrongRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (40)

- PMS FormatDocument4 pagesPMS Formatzodaq0% (1)

- Sample Korean Employment ContractDocument7 pagesSample Korean Employment ContractNhat TamNo ratings yet

- IIFM Placement Brochure 2022-24-4 Pages Final LRDocument4 pagesIIFM Placement Brochure 2022-24-4 Pages Final LRPushkar ParasharNo ratings yet

- New TIP Course 1 DepEd Teacher 1Document89 pagesNew TIP Course 1 DepEd Teacher 1Spyk SialanaNo ratings yet

- Spiderwoman Theatre challenges colonial stereotypesDocument12 pagesSpiderwoman Theatre challenges colonial stereotypesdenisebandeiraNo ratings yet

- Architectural Design-Collective Intelligence in Design (2006-0910)Document138 pagesArchitectural Design-Collective Intelligence in Design (2006-0910)diana100% (3)

- Health and Safety Assessment Form and Plagiarism StatementDocument9 pagesHealth and Safety Assessment Form and Plagiarism StatementMo AlijandroNo ratings yet

- Definition of JurisprudenceDocument32 pagesDefinition of JurisprudenceGaurav KumarNo ratings yet

- 00 Social Science 1 Course OutlineDocument2 pages00 Social Science 1 Course OutlineKenneth Dionysus SantosNo ratings yet

- 2016.05.14-18 APA Preliminary ProgramDocument28 pages2016.05.14-18 APA Preliminary ProgramhungryscribeNo ratings yet

- Workforce: A Call To ActionDocument40 pagesWorkforce: A Call To ActionEntercomSTLNo ratings yet

- Marketing Strategies for Maldivian ProductsDocument5 pagesMarketing Strategies for Maldivian ProductsCalistus FernandoNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Metacognition: Presented By: Rocelyn Mae B. Herrera UE02 - Facilitating Learning Prof. Russel V. SantosDocument14 pagesModule 1: Metacognition: Presented By: Rocelyn Mae B. Herrera UE02 - Facilitating Learning Prof. Russel V. SantosUe ucuNo ratings yet

- CHN QUESTIONSDocument19 pagesCHN QUESTIONSChamCham Aquino100% (3)

- Course Syllabus & Schedule: ACC 202 - I ADocument8 pagesCourse Syllabus & Schedule: ACC 202 - I Aapi-291790077No ratings yet

- (Doctrine of Preferred Freedom (Hierarchy of Rights) - Valmores V. AchacosoDocument16 pages(Doctrine of Preferred Freedom (Hierarchy of Rights) - Valmores V. AchacosoAngel CabanNo ratings yet

- 2016-17 District CalendarDocument1 page2016-17 District Calendarapi-311229971No ratings yet

- A Technical Report On Student IndustrialDocument50 pagesA Technical Report On Student IndustrialDavid OluwapelumiNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log (DLL) in English 9: Page 1 of 5Document5 pagesDaily Lesson Log (DLL) in English 9: Page 1 of 5Heart SophieNo ratings yet

- Dlsu Thesis SampleDocument4 pagesDlsu Thesis Samplereginalouisianaspcneworleans100% (2)

- Assertive Training and Self-EsteemDocument3 pagesAssertive Training and Self-EsteemKuldeep singhNo ratings yet

- Cobit Casestudy TIBODocument22 pagesCobit Casestudy TIBOAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary - More Than Words ThornburyDocument5 pagesVocabulary - More Than Words Thornburya aNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan TemplateDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Templateapi-284408118No ratings yet

- BA 2 (Chapter 2 Personnel Program & Policies)Document2 pagesBA 2 (Chapter 2 Personnel Program & Policies)Cleene100% (6)

- School Grade Level 2 Teacher Cristelle L. de Gucena Subject English Time of Teaching Quarter First-W1Document66 pagesSchool Grade Level 2 Teacher Cristelle L. de Gucena Subject English Time of Teaching Quarter First-W1cristelle de gucenaNo ratings yet

- Short immobilization with early motion increases Achilles tendon healingDocument1 pageShort immobilization with early motion increases Achilles tendon healingCleber PimentaNo ratings yet

- Application Summary Group InformationDocument12 pagesApplication Summary Group InformationKiana MirNo ratings yet

- Garcia Thesis ProposalDocument22 pagesGarcia Thesis ProposalMarion Jeuss GarciaNo ratings yet

- Code of The Republic Moldova On Science and InnovationsDocument51 pagesCode of The Republic Moldova On Science and InnovationsArtur CotrutaNo ratings yet