Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Culture of Dance During The Spanish Occupation

Uploaded by

Raissa AzarconOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Culture of Dance During The Spanish Occupation

Uploaded by

Raissa AzarconCopyright:

Available Formats

CULTURE OF DANCE DURING THE SPANISH OCCUPATION By Raissa Azarcon Dance as a Tool of Oppression In school, we are taught to believe

that Spanish colonizers won us over using this quick and savvy formulathat of the cross and the sword. Spanish friars and government officials employed Catholicism to transform native consciousness into what they vehemently call proper and civil. They introduced their religion to native Filipinos not for humanitarian reason but to further their empire and soften and impede any threat of rebellion and revolt. Hence, with the introduction of Catholicism came a paradigm shift that transformed how native Filipinos see and view the world. European cultural ideas were assimilated to indigenous traditions. These influences were predominantly apparent in the lowland and coastal areas since trade and barter usually took place in this areas. Spanish friars led the Hispanization of the Philippine archipelago. They implemented rules that bound Filipinos to colonial practices and prohibit them in returning back to what they were once accustomed of. Friars ordered the burning of any written documents that would seem detrimental to their reign. Primitive texts were burned and along with them, the rich tradition of our pre-hispanic past. Our music was modified; the way we dressed was altered to better suit their preference; our tribal dances was overturned but not completely vanquished. A syncretic view was applied. Foreign dances were Filipinized. Each locality developed their own version of foreign dances. Cuban tango evolved into Habanera Botolena in Zambales, the French Minuet was adopted by the folks of Camarines Sur and eventually became known as Minuete Yano, and the Spanish fandango was localized as Pandango nationwide. Henceforth, dance has become a convenient tool for the colonizers to tame the natives into subjugation and surrender. Dance as a Way to Conform In times of war and social unrest, wealthy Filipinos were the most apprehensive of all mainly because they want to secure their estates and properties from possible embezzlement and damage. They have money to burn to make sure that their wealth will not perish along with their nation and so, with this kind of mindset, they rather played it safe. They did not show any rage or express any disagreement to the rule of Spaniards. Instead, they fraternized with the enemies and showered them with gifts and half-hearted praises. And to further differentiate them from the rest of the Filipinos, they adopted the ways and behaviour of Spaniards. They embraced anything that had to do with Spain and threw their national identity in the wind. They were the ilustrados, the enlightened ones, the ones who were able to afford education, the bourgeois families who socialized and partook in elegant Hispanic gatherings, the ones who were the first social climbers, the first to have been paralyzed by colonial mentality. They refused to dance the ancestral dances in the fear of being singled out as an indio by their Spanish peers. Thus, they did what was expected of them. They donned moves of Western descent. This was in order to maintain their status quo and to retain their reputation. This phenomenon brought forth the concept of Maria Clara Suite, a collective name for all the Hispanic-influenced dances that proliferated during the reign of Spain in our country. It was named after one of the lead

characters of Rizals highly-acclaimed novel Noli Me Tangere. Maria Clara is the love interest of Crisostomo Ibarra and was later on discovered to be the daughter of the main antagonist, Padre Damaso. Dance and Courtship In the rural areas where Spanish influence was not yet firmly established, Filipinos have maintained the distinct quality of their ritual dances. There are dances that are meant to reflect how women are to be treated by men, and how the mechanics of courtship should be properly observed and handled by the youth. For example, in the dance called Sayaw Santa Isabel, the male dances hold hankerschiefs for the woman to hold. This suggests that suitors were forbidden to hold the hand of the maiden they like. And moreso suggest being discreet when in front of the opposite sex. Dance of the Untouched Not all were overpowered by the Spanish forces; there are some who remained untouched and unconquered by the Spanish regime. Some areas of the Philippines were not easily shackled by the deadly combination of sword and cross. Their dances remained free of colonial influence, and have regionalistic temperament in them. Dances under this category reflected the customs of small communities and are further influenced by the geographic, economic, and social conditions prevalent in the area. Maglalatik is of this kind. It is a war dance performed by the Tagalogs and which depicts a fight between Christians and Muslims over the latik, a kind of coconut residue. Its distinct quality lies in the fact that the dance makes use of coconut shells instead of sword, a characteristic that contradicts the common supposition that every war dance should use war gears and swords for props. In this context, the Tagalogs made use of what was easily found in their immediate environment and since coconut is ubiquitously growing and abundant, it was no surprise that they made it the primary props of their dance. Another good example would be the Katlo, a dance native in Bulacan. It reflected one of the major activities of Filipinosthat of rice-planting and harvesting. Katlo is a dance which re-enacts folk people while they are pounding the rice. Then, under the same roof can be found the Tioka, a dance originating from Laguna. This one acts out the movements of men while they are threshing rice. And lastly, to give tribute to the coconut-growers, the occupational dance called Mananguete is performed in the coconutgrowing region of the country. This dance depicts, by the use of pantomime, the complete stages of gathering tuba fermented liquid from a coconut bud that served as a famous liquor to rural folks. Reference: Alejandro, Reynaldo. Sayaw: Philippine Dances Manila. National Bookstore. 2002.

You might also like

- Keyboard CourseDocument166 pagesKeyboard CourseNoel Moncrieffe100% (4)

- Plato's Theory of LanguageDocument21 pagesPlato's Theory of LanguageTonia KyriakoulakouNo ratings yet

- Guide To Oboe Reedmaking 2021Document21 pagesGuide To Oboe Reedmaking 2021Katoka Felix100% (1)

- Philippine Folk DanceDocument4 pagesPhilippine Folk DanceMaria Cecilia ReyesNo ratings yet

- Man's shrinking distances bring no true nearnessDocument13 pagesMan's shrinking distances bring no true nearnessRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Magazine: The Sound Engineer JulyDocument44 pagesMagazine: The Sound Engineer JulyMatthew WalkerNo ratings yet

- Auteur in Indian Films: Sanjay Leela Bhansali and Mani RatnamDocument9 pagesAuteur in Indian Films: Sanjay Leela Bhansali and Mani RatnamSubodh MintoNo ratings yet

- Score Castle-Park-March Composer Timo ForsstromDocument21 pagesScore Castle-Park-March Composer Timo ForsstromDaedricLord LebanidzeNo ratings yet

- Ponce Gavotte PDFDocument77 pagesPonce Gavotte PDFAmadeu RosaNo ratings yet

- Lsi 2007Document61 pagesLsi 2007Andre Vare100% (1)

- History of Arnis Martial ArtDocument2 pagesHistory of Arnis Martial ArtOdyNo ratings yet

- History and Origin of ArnisDocument1 pageHistory and Origin of ArnisHoney GuideNo ratings yet

- History of Table Tennis and ArnisDocument3 pagesHistory of Table Tennis and ArnisMarvin Lubongan DacuagNo ratings yet

- ArnisDocument2 pagesArnisChrysler GepigaNo ratings yet

- The Philippines Is An Island Nation Rich in Both Culture and History. The Filipino Martial Art ofDocument2 pagesThe Philippines Is An Island Nation Rich in Both Culture and History. The Filipino Martial Art ofNelj Manahan CarnasoNo ratings yet

- Al AndalusDocument1 pageAl AndalusLaura Maria GalanNo ratings yet

- NACIREMA TRIBE'S UNUSUAL RITUALS AND SOCIAL STRUCTURESDocument2 pagesNACIREMA TRIBE'S UNUSUAL RITUALS AND SOCIAL STRUCTURESphong_trinhNo ratings yet

- PP vs. MierDocument2 pagesPP vs. MierAnnemargarettejustine CruzNo ratings yet

- Book Review - ABHIMANYU (Amar Chitra Katha)Document1 pageBook Review - ABHIMANYU (Amar Chitra Katha)Nalini Kanth100% (1)

- I UbermenschDocument2 pagesI UbermenschBharatwaj IyerNo ratings yet

- NotesDocument3 pagesNotesAyesha MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Opinion On Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of IndependenceDocument2 pagesOpinion On Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of IndependenceSmolenic AndaNo ratings yet

- BIG LOVE - Auditions by Sign-Up Pittsburgh Playhouse, Upstairs TheatreDocument3 pagesBIG LOVE - Auditions by Sign-Up Pittsburgh Playhouse, Upstairs TheatreCharles BaileyNo ratings yet

- Paul Casquejo - RespondentDocument1 pagePaul Casquejo - RespondentPaul Gabriel CasquejoNo ratings yet

- The First Indian War of Indepdence and AssamDocument2 pagesThe First Indian War of Indepdence and AssamUpasana HazarikaNo ratings yet

- Bi-Snow White and The HuntsmanDocument2 pagesBi-Snow White and The HuntsmanTracy WmhNo ratings yet

- HBL ReportDocument63 pagesHBL ReportShahid Mehmood100% (6)

- Sexual Harassment - Manini MishraDocument2 pagesSexual Harassment - Manini MishraManini MishraNo ratings yet

- Ioc Passage ScriptDocument3 pagesIoc Passage ScriptVishal MokashiNo ratings yet

- Character Sketch of Griffin: The Invisible ManDocument1 pageCharacter Sketch of Griffin: The Invisible ManVenus100% (3)

- F.Sc English exam questionsDocument1 pageF.Sc English exam questionsQaisar RiazNo ratings yet

- Narrativecommonassessment RishavguptaDocument2 pagesNarrativecommonassessment Rishavguptaapi-358111189No ratings yet

- Opposition On Early ConvertsDocument2 pagesOpposition On Early ConvertsTaha YousafNo ratings yet

- 47 RoninDocument2 pages47 Roninapi-239995826No ratings yet

- LordofthefliesDocument3 pagesLordofthefliesapi-297027975No ratings yet

- Learning Activity 1.1 Theogony: An AnalysisDocument2 pagesLearning Activity 1.1 Theogony: An AnalysisPAM GEYSER TAYCONo ratings yet

- Chapter I - The Man in The CloakDocument3 pagesChapter I - The Man in The CloakCristina CotrutaNo ratings yet

- Inggris Minat Review Avenger Infinity WarDocument3 pagesInggris Minat Review Avenger Infinity WarMalleusNo ratings yet

- How Islam is Growing Stronger Despite 9/11 AttacksDocument1 pageHow Islam is Growing Stronger Despite 9/11 AttacksksahunkNo ratings yet

- Using Facts, Quotes, and Stats in Academic WritingDocument3 pagesUsing Facts, Quotes, and Stats in Academic WritingDiana Patricia Alcala PerezNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Terms ExplainedDocument3 pagesLinguistic Terms ExplainedFeim HajrullahuNo ratings yet

- Prvi Pismeni Zadatak 3Document3 pagesPrvi Pismeni Zadatak 3Zaklina RistovicNo ratings yet

- Scarcely: Learn To PronounceDocument3 pagesScarcely: Learn To Pronounceግደይ ዓደይ ዓይነይ ኪሮስNo ratings yet

- LiterarycriticismessayDocument3 pagesLiterarycriticismessayapi-349989510No ratings yet

- Handout in 21st Century LiteratureDocument1 pageHandout in 21st Century LiteratureJoseph Fulgar LopezNo ratings yet

- Norman Foster's inspiring career and sustainable architecture visionDocument2 pagesNorman Foster's inspiring career and sustainable architecture visionsharvariNo ratings yet

- Radio Analysis 1Document1 pageRadio Analysis 1taranbasiNo ratings yet

- GEK1519 Concert ReviewDocument3 pagesGEK1519 Concert ReviewZu Jian LeeNo ratings yet

- Scene: Old Woman Sitting in A Dark, Dreary RoomDocument2 pagesScene: Old Woman Sitting in A Dark, Dreary RoomNatMelPalmNo ratings yet

- Mauro Ganzon, Petitioner, Vs - Court of Appeals and Gelacio E. Tumambing, Respondents G.R. No. L-48757 May 30, 1988Document1 pageMauro Ganzon, Petitioner, Vs - Court of Appeals and Gelacio E. Tumambing, Respondents G.R. No. L-48757 May 30, 1988John Patrick GarciaNo ratings yet

- International Humanitarian Law (Trial Technique)Document2 pagesInternational Humanitarian Law (Trial Technique)Michael VillalonNo ratings yet

- Video Games Is The Evolution of EntertainmentDocument1 pageVideo Games Is The Evolution of EntertainmentMichael SabaricosNo ratings yet

- Mauro Ganzon vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. L-48757 May 30, 1988 Sarmiento, J. FactsDocument1 pageMauro Ganzon vs. Court of Appeals G.R. No. L-48757 May 30, 1988 Sarmiento, J. FactsNichole Patricia PedriñaNo ratings yet

- Animal Farm Chapter 2 ReviewDocument1 pageAnimal Farm Chapter 2 ReviewAnggie SuharginNo ratings yet

- Differences and Similarities Between The Our Father Prayer and Psalm 5Document2 pagesDifferences and Similarities Between The Our Father Prayer and Psalm 5api-356016506No ratings yet

- Art G1Tri1Document2 pagesArt G1Tri1lorenzomoloNo ratings yet

- Purrfectlynaturals Extra CharactersDocument3 pagesPurrfectlynaturals Extra CharacterspurrfectlynaturalNo ratings yet

- YevaanDocument2 pagesYevaanMarion Yvann SinsonNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument2 pagesBibliographymagilNo ratings yet

- Carragie by Air QuestionDocument3 pagesCarragie by Air QuestionSean WolfeNo ratings yet

- Topic 7 Exercise 1 Read The Extract of "The Unicorn in The Garden" by James Thurbar and Answer The Questions That FollowDocument3 pagesTopic 7 Exercise 1 Read The Extract of "The Unicorn in The Garden" by James Thurbar and Answer The Questions That Follownseir_alNo ratings yet

- Driver (1976), You Might Find Trouble With The Police. But If Your Skin Color Is Black, There Is ADocument2 pagesDriver (1976), You Might Find Trouble With The Police. But If Your Skin Color Is Black, There Is Aapi-298580735No ratings yet

- ReligionDocument1 pageReligionZahir Jayvee Gayak IINo ratings yet

- Creative Writing Workshop - List Poem on Need for AirDocument1 pageCreative Writing Workshop - List Poem on Need for AirPatrik FreiNo ratings yet

- Anti RapeDocument2 pagesAnti RapeOwolabi PetersNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Types of Empirical Studies (Descriptive, Qualitative, QuantitativeDocument1 pageLesson 2: Types of Empirical Studies (Descriptive, Qualitative, QuantitativeShaukat Ali AmlaniNo ratings yet

- CopyofbillcreatorDocument2 pagesCopyofbillcreatorapi-336971323No ratings yet

- Episode 38Document2 pagesEpisode 38collectionuNo ratings yet

- That Is Why Developmental Biology Helped To Establish Oncology and Has Continued To Help Mold ItDocument3 pagesThat Is Why Developmental Biology Helped To Establish Oncology and Has Continued To Help Mold ItVeyari RamirezNo ratings yet

- Marina Cruz Redefining NostalgiaDocument4 pagesMarina Cruz Redefining NostalgiaRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Repressed Trauma and Identity in BlueDocument13 pagesRepressed Trauma and Identity in BlueRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- The Image As MemorialDocument9 pagesThe Image As MemorialRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Appreciation of The Natural EnvironmentDocument14 pagesAesthetic Appreciation of The Natural EnvironmentRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Natural Conditions For Coffee CultureDocument13 pagesNatural Conditions For Coffee CultureRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Coffee, Connoiseurship, and An Ethnomethodologically-Informed Sociology of TasteDocument16 pagesCoffee, Connoiseurship, and An Ethnomethodologically-Informed Sociology of TasteRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Coffee, Connoiseurship, and An Ethnomethodologically-Informed Sociology of TasteDocument16 pagesCoffee, Connoiseurship, and An Ethnomethodologically-Informed Sociology of TasteRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Talk About Love in Relation To EthicsDocument1 pageWhy Do We Talk About Love in Relation To EthicsRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Coffehouses and CultureDocument8 pagesCoffehouses and CultureRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- The Alienated IDocument2 pagesThe Alienated IRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- On "Death: at Death's Door": A GENDER APPROACH ON THE REPRESENTATION OF DEATH IN NEIL GAIMAN'S SANDMAN SERIESDocument17 pagesOn "Death: at Death's Door": A GENDER APPROACH ON THE REPRESENTATION OF DEATH IN NEIL GAIMAN'S SANDMAN SERIESRaissa AzarconNo ratings yet

- Acs G Assignment TotalDocument2 pagesAcs G Assignment Totalଦେବୀ ପ୍ରସାଦ ପଟନାୟକNo ratings yet

- TubaDocument2 pagesTubaAndrei OloieriNo ratings yet

- Portofolio Bahasa Inggris: Disusun Oleh: Gigih Satria Pradana Xii Ips 1 0030551620 / 20231339Document18 pagesPortofolio Bahasa Inggris: Disusun Oleh: Gigih Satria Pradana Xii Ips 1 0030551620 / 20231339Hanan Halim AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Summer StoryDocument172 pagesSummer StoryJim ChihNo ratings yet

- Contoh Surat Pen Pa1Document9 pagesContoh Surat Pen Pa1fendy100% (1)

- Psychedelic Dream PopDocument1 pagePsychedelic Dream PopVelvetBeachNo ratings yet

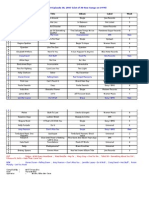

- Batangas School Division Region IV-ADocument8 pagesBatangas School Division Region IV-AGladys Gutierrez100% (1)

- New Version 2nd Quarter Exam Grade 10Document3 pagesNew Version 2nd Quarter Exam Grade 10dieza martinadaNo ratings yet

- Timbrado de Nomina 298 - Cfdi - Actulizados Magist - EstDocument14 pagesTimbrado de Nomina 298 - Cfdi - Actulizados Magist - EstOliver Y shuaben Pérez OrtizNo ratings yet

- Underworld2 - 5m2b Heli Ride - Track On Beltrami SiteDocument21 pagesUnderworld2 - 5m2b Heli Ride - Track On Beltrami Sitekip kipNo ratings yet

- DELIRIUM: Book Club GuideDocument4 pagesDELIRIUM: Book Club GuideEpicReadsNo ratings yet

- Monthly art test reviewDocument3 pagesMonthly art test reviewLavander BlushNo ratings yet

- Blue Bossa Bass LineDocument1 pageBlue Bossa Bass Linem00sygrlNo ratings yet

- SPRING'S SONGS OF LOVEDocument4 pagesSPRING'S SONGS OF LOVERenata GeorgescuNo ratings yet

- A Musical Fantasy: Commissioned by KunstfactorDocument3 pagesA Musical Fantasy: Commissioned by KunstfactorMarlon AgapitoNo ratings yet

- The Harlem Renaissance MovementDocument8 pagesThe Harlem Renaissance MovementLaura CarniceroNo ratings yet

- History of Hip HopDocument4 pagesHistory of Hip HopFarah JNo ratings yet

- List of Songs Torrins Music 2021-22Document3 pagesList of Songs Torrins Music 2021-22Ankit SappalNo ratings yet

- CV PDFDocument5 pagesCV PDFapi-348777019No ratings yet

- SC Graded Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSC Graded Lesson Planapi-643328425No ratings yet

- Steve JobDocument4 pagesSteve JobLaurentiusAndreNo ratings yet

- Piano Pieces Repertoire (Classical)Document2 pagesPiano Pieces Repertoire (Classical)Ang Dun JieNo ratings yet