Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Help, Don't Hover: Thoughts For Parents of College Students

Uploaded by

Robert MassaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Help, Don't Hover: Thoughts For Parents of College Students

Uploaded by

Robert MassaCopyright:

Available Formats

Help, Dont Hover: Thoughts for Parents of College Students By Robert J. Massa I had parents. I am a parent.

Some of my best friends are parents. So why do I get uneasy when a mother calls to arrange an admission interview for her son o r when parents are the only ones to ask questions during a group information ses sion or when a father tells me that we are applying to six top colleges? And lest one think it ends with college admissions, my colleagues in academic an d student affairs can relate stories of parents wanting to attend judicial heari ngs or challenging a professor about their daughters grades. My parents had trou ble even spelling university. In their book, Millenials go to College, Neil Howe and William Strauss speak of hel icopter parents, defining our generation of parents as always hovering ultra-prote ctive, unwilling to let go and enlisting the team (physician, lawyer, psychiatri st) to assert a variety of special needs and interest. When parents dont get the ir way, Howe and Strauss say, they threaten to take their business elsewhere or s ue. When my children were growing up, my wife and i joined our neighbors in the omni present caravan to Little League games, volleyball matches, piano lessons and sc outs. Was this programming for our children wrong? Were the values we tried to t each our kids (working toward a goal, integrity, cooperation and respect) misgui ded? I think not. But somewhere along the way, many of us mistook our needs to see our children excel with their needs to be kids. Enter the college-prep mom and dad. With inquisitive parents in tow, students seem more nervous than in the past dur ing a campus visit. After admission, the parent typically writes an appeal to t he scholarship committee about why the child deserves a monetary award. And if the student is placed on the wait list or denied admission, the parent, with his ego bruised more than his sons, calls to put pressure on the admission officer. Despite our best efforts to impress upon parents that their children should take charge of the admission process, the helicopter blades continue to whirl. I ha ve heard student affairs professionals at orientation programs advise parents to allow their children to handle their own challenges and to work with college of ficials to instill in them a sense of confidence and a willingness to take ris ks. Upperclass students during freshman orientation often perform skits reveali ng the silliness of parent over-involvement. Everyone laughs and gets it. Then, parents leave, a terrible roommate situation or a class scheduling conflict occu rs, and the phone calls to the dean begin. A college is a special nt to go unnoticed and annot help students to s intervene every time all for help. place. Young people seeking only a credential and who wa unchallenged need not apply. College faculty and staff c become independent thinkers and problem solvers if parent their emerging adults (as the New York Times called them) c

As difficult as it is for parents like me to avoid, interference of this sort un dercuts the large investment we make in our childrens education. Instead, parents should listen, reflect and advise. Let the faculty and staff do what they do b est help young people become engaged citizens and leaders in this complex world. And so, I solemnly swear that the next time my daughter asks me to call the comp uter center director at her college to intervene on her behalf, I will firmly bi te my tongue and politely say no.

Robert J. Massa is Vice President for Communications at Lafayette College in Eas ton, PA. This piece, first written in 2005, continues to be timely today.

You might also like

- Reflections On 40 Years in Higher Education and What's NextDocument3 pagesReflections On 40 Years in Higher Education and What's NextRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- Pell Grant and AccessDocument3 pagesPell Grant and AccessRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- Admissions Marketing in A Digital WorldDocument2 pagesAdmissions Marketing in A Digital WorldRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- Under-Enrollment Doesn't "Just Happen"Document2 pagesUnder-Enrollment Doesn't "Just Happen"Robert MassaNo ratings yet

- The Future Is NowDocument4 pagesThe Future Is NowRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- The Value of A Small Undergraduate College EducationDocument1 pageThe Value of A Small Undergraduate College EducationRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- Robert Massa - Increasing The Male-To-Female Ratio in CollegesDocument1 pageRobert Massa - Increasing The Male-To-Female Ratio in CollegesRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- Merit Aid: Can Colleges Continue To Escalate Discounts?Document2 pagesMerit Aid: Can Colleges Continue To Escalate Discounts?Robert MassaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Enrollment Management: An IntroductionDocument42 pagesStrategic Enrollment Management: An IntroductionRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- How To Improve College Student Aid DisclosureDocument2 pagesHow To Improve College Student Aid DisclosureRobert MassaNo ratings yet

- Athletics Oped 0603Document2 pagesAthletics Oped 0603Robert MassaNo ratings yet

- Cost of Competition12Document2 pagesCost of Competition12Robert MassaNo ratings yet

- Aid Cost612Document2 pagesAid Cost612Robert MassaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Fichas Por Números INGLÉSDocument80 pagesFichas Por Números INGLÉSoskr2191No ratings yet

- Rizal Memorial Colleges, IncDocument9 pagesRizal Memorial Colleges, Incmark ceasarNo ratings yet

- Brochure MathDocument2 pagesBrochure Mathapi-429687566No ratings yet

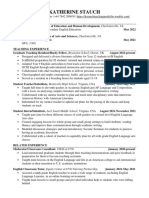

- Stauch Teaching ResumeDocument2 pagesStauch Teaching Resumeapi-578683335No ratings yet

- Savage Inequalities Reading ReflectionDocument3 pagesSavage Inequalities Reading Reflectionapi-367005642No ratings yet

- Mei3c Glossary Chapter 1 Lorena Vega LimónDocument3 pagesMei3c Glossary Chapter 1 Lorena Vega LimónLorena Vega LimonNo ratings yet

- Top-rated teachers at Sofornio Cordovero schoolDocument1 pageTop-rated teachers at Sofornio Cordovero schoolKira Reyzzel Catamin100% (1)

- Developing Your Yoga Teaching ScriptDocument31 pagesDeveloping Your Yoga Teaching ScriptLee Pin Wei100% (16)

- Lesson Plan Form SmepDocument8 pagesLesson Plan Form SmepQueenie Marie Obial AlasNo ratings yet

- Chakulimba (Sociology 1)Document5 pagesChakulimba (Sociology 1)Mukupa Dominic ChitupilaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Computer To The Academic Performance of The Grade 11 ICT Students of Rizal High SchoolDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Computer To The Academic Performance of The Grade 11 ICT Students of Rizal High SchoolSaikouuu Arashi100% (1)

- TPR Lesson on HobbiesDocument3 pagesTPR Lesson on HobbiesVikaNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Japanese Junior High School Textbooks As Pronunciation Teaching MaterialsDocument5 pagesAn Analysis of Japanese Junior High School Textbooks As Pronunciation Teaching Materialsm7294207351No ratings yet

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: I. ObjectivesDocument4 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: I. ObjectivesMary Joselyn BodionganNo ratings yet

- Department of Vocational Education & Training: Industrial Training Institute, Aundh, Pune - 07Document43 pagesDepartment of Vocational Education & Training: Industrial Training Institute, Aundh, Pune - 07Joint Chief Officer, MB MHADANo ratings yet

- Creative writing techniques and learners' success storiesDocument7 pagesCreative writing techniques and learners' success storiesAzmaine SanjanNo ratings yet

- Early Language Learning Policy HandbookDocument30 pagesEarly Language Learning Policy Handbookmontecito2No ratings yet

- Talingting ES NRM Narrative ReportDocument2 pagesTalingting ES NRM Narrative ReportJulie Ann IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Bodily Kinesthetic IntelligenceDocument11 pagesBodily Kinesthetic Intelligencestolen mechieduc100% (1)

- Field Study 5 Learning Assessment StrategiesDocument25 pagesField Study 5 Learning Assessment StrategiesCA T He50% (18)

- Jordan & Metais, 2000Document5 pagesJordan & Metais, 2000Simon ReidNo ratings yet

- Literacy Ideologies Cadiero-KaplanDocument10 pagesLiteracy Ideologies Cadiero-Kaplanapi-220477929No ratings yet

- Lockman-Educ-765-Portfolio-Project FinalDocument24 pagesLockman-Educ-765-Portfolio-Project Finalapi-321807037No ratings yet

- Amazing Grace Diagram Lesson Plan 2 6 17Document2 pagesAmazing Grace Diagram Lesson Plan 2 6 17api-310967404No ratings yet

- Danielson Pre-Observation Form 409Document2 pagesDanielson Pre-Observation Form 409api-28624516150% (2)

- About The TOEFL iBT TestDocument2 pagesAbout The TOEFL iBT TestAulia Yuliyanti WulandariNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan Grade 7 - MathematicsDocument3 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan Grade 7 - MathematicsjheNo ratings yet

- Swiss Government Excellence ScholarshipsDocument3 pagesSwiss Government Excellence ScholarshipsG88_No ratings yet

- Tracy's Swing ProgressionsDocument4 pagesTracy's Swing ProgressionsPicklehead McSpazatronNo ratings yet

- Plan for Continuing Teacher DevelopmentDocument12 pagesPlan for Continuing Teacher DevelopmentHANNA GALE91% (11)