Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Uploaded by

rachim040 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

324 views15 pagesNicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

324 views15 pagesNicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Uploaded by

rachim04Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

Rogue Trader: Nicholas Leeson

How did one of the worlds oldest and most distinguished

investment banks allow a single man to cause its collapse?

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-2

1. What was Nick Leesons strategy to earn trading profits on

derivatives?

2. What went wrong that caused his strategy to fail?

3. Why did Nick Leeson establish a bogus error account (88888) when a

legitimate account (99002) already existed?

4. Why did Barings and its auditors not discover that the error account

was used by Leeson for unauthorized trading?

5. Why did none of the regulatory authorities in Singapore, Japan, and

the United Kingdom not discover the true use of the error account?

6. Why was Barings Bank willing to transfer large cash sums to Barings

Futures Singapore?

7. Why did the attempt by the Bank of England to organize a bailout for

Barings fail?

8. Suggest regulatory and management reforms that might prevent a

future debacle of the type that bankrupted Barings.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-3

Exhibit 1

Key Events

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-4

1. What was Nick Leesons strategy to earn trading profits on

derivatives?

Nick Leeson was trading futures and options on the Nikkei 225, an index of

Japanese securities.

He was long Nikkei 225 futures, short Japanese government bond futures,

and short both put and call options on the Nikkei Index.

He was betting that the Nikkei index would rise, but instead, it fell, causing

him to lose $1.39 billion.

2. What went wrong that caused his strategy to fail?

Nick Leesons strategy failed because the Nikkei 225 index kept falling

while he continued to bet that it would rise he just didnt know when to

quit and take his losses.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-5

3. Why did Nick Leeson establish a bogus error account (88888) when a

legitimate account (99002) already existed?

Nick Leeson established a bogus error account (88888) when a legitimate account

(99002) already existed in order to conceal his unauthorized trading activities.

While the legitimate error account was known to Barings Securities in London, the

bogus account was not.

However, the bogus account was known to SIMEX as a customer account, not as an

error account. In this way Leeson could hide his balances and losses from London

but not Singapore.

One the other hand, SIMEX thought the bogus error account, 88888, was a

legitimate customer account rather than a proprietary Barings account.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-6

4.Why did Barings and its auditors not discover that the error account was

used by Leeson for unauthorized trading?

Internal Reasons. Leeson engaged in unauthorized trading, as well as fraud. However, it is clear that he

was hidden in the organized chaos that characterized Barings. There were no clearly laid down reporting

lines with regard to Leeson, through the management chain to Ron Baker [Head of Financial Products

Group for Barings] (Bank of England, p. 235). In fact, it seems there were several people responsible for

monitoring Leesons performance, each of whom assumed the other was watching more closely than he.

In August 1994, James Baker completed an internal audit of the Singapore office. He made several

recommendations that should have alerted Barings executives to the potential for unauthorized trading: 1)

segregation of front and back office activitiesa fundamental principle in the industry, 2) a

comprehensive review of Leesons funding requirements, and 3) position limits on Leesons activities.

None of these had been acted upon by the time of the banks collapse.

With regard to the first concern, Simon Jones, Director of BFS and Finance Director of BSS, in

Singapore, offered assurances that he would address the segregation issue. However, he never took

action to segregate Leesons front and back office activities. Tony Hawes, Barings Treasurer in London

agreed to complete a review of the funding requirements within the coming year. Ian Hopkins, Director

and Head of Treasury and Risk in London, placed the issue of position limits on the risk committees

agenda, but it had not been decided when the collapse occurred.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-7

4.Why did Barings and its auditors not discover that the error account was

used by Leeson for unauthorized trading? (continued)

According to the Bank of England report, senior management in London considered Jones a

poor communicator and were concerned that he was not as involved as he should have been

in the affairs of BFS. In fact, Peter Norris, the chief executive officer for Baring Securities

Limited wanted to replace Jones. Jones, however, was protected by James Bax, Managing

Director of Baring Securities Singapore, who was well liked in London.

The Bank of England also found fault with the process of funding Leesons activities from

London. First, there was no clear understanding of whether the funds were needed for clients

or for Barings own accounts, making reconciliation impossible. Second, given the large

amounts, credit checks should have been completed as well. The report places the

responsibility for the lack of due diligence with Tony Hawes, Ian Hopkins, and the

Chairman of the Barings Credit Committee.

The issue of proper reconciliation arose as early as April 1992 when Gordon Bowser, the

risk manager in London, recommended that a reconciliation process be developed.

Unfortunately, Bowser left Simon Jones and Tony Dickel, who had sent Leeson to

Singapore, to agree on a procedure. With internal conflict over who was responsible for

Leesons activities, no agreement was reached between those two, and Leeson was left to

establish reconciliation procedures for himself.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-8

4. Why did Barings and its auditors not discover that the error account

was used by Leeson for unauthorized trading? (continued)

There are numerous similar examples of internal conflict benefitting Leesons covert

trading throughout the three years. But one of the late failures occurred in January

1995 when SIMEX raised concern over Barings ability to meet its large margins. In

a letter dated January 11, 1995, and addressed to Simon Jones, SIMEX officials

noted that there should have been an additional $100 million in the margin account

for 88888. Jones passed the letter to Leeson to draft a response.

External Reasons. In January 1995, SIMEX was getting close to Leesons activities,

but had not yet managed to determine what was happening. In response to a second

letter dated January 27, 1995 and sent to James Bax in Singapore, SIMEX expressed

concerns regarding Barings ability to fund its margin calls. Bax referred the letter to

London, and SIMEX received reassurance that opposite positions were held in

Japan. Unfortunately, SIMEX officials did not follow up with the Osaka Stock

Exchange to verify the existence of those positions.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-9

5. Why did none of the regulatory authorities in Singapore, Japan, and

the United Kingdom not discover the true use of the error account?

SIMEX assumed that Barings was hedging and not speculating when it granted an

exemption on the number of contracts that Barings could hold. Due to Barings

reputation for being a conservative firm, the exchange and clearing houses were

operating under a false sense of security.

In addition, the speculative position of Barings was hidden due to use of an omnibus

account to clear trades. With an omnibus account, the identity of the brokers

customers is hidden from the exchange and the clearinghouse.

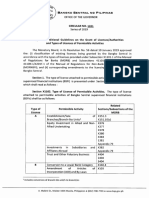

Several incidents in London also made Leesons activities easier to manage and

hide. The Bank of England had a Large Exposure rule where a bank could not lend

more than 25% of its capital to any one entity. However, Barings had requested that

an exception be made, arguing that an exchange should not be treated as one entity.

Christopher Thompson, the supervisor in charge of Barings activities, acknowledged

receipt of the request and said he would review it. In the meantime, he offered an

informal concession for Japan, which Barings took the liberty of also applying to

Singapore and Hong Kong. Thompson did not respond for a year, and when he did

on February 1, 1995, the answer was that an exception could not be made for

exchanges and that the positions taken under the informal concession should be

unwound.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-10

5. Why did none of the regulatory authorities in Singapore,

Japan, and the United Kingdom not discover the true use of

the error account? (continued)

The second incident was the solo-consolidation of Baring Securities Ltd

and Baring Brothers & Co.

This allowed them to be treated as one entity for capital adequacy and large

exposure purposes. This meant Leeson had access to a larger amount of

capital.

The Bank of England found the process of solo-consolidation to have been

too informal and the results to have facilitated Leesons fraudulent

activities.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-11

6. Why was Barings Bank willing to transfer large cash sums

to Barings Futures Singapore?

Barings Bank believed that the large cash sums transferred to Barings

Futures Singapore was for loans to customers as portrayed on the Barings

Futures Singapore balance sheet.

7. Why did the attempt by the Bank of England to organize a

bailout for Barings fail?

The attempt by the Bank of England to organize a bailout for Barings failed

because no one would assume the contingent risk of additional, but as yet

undiscovered losses.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-12

8. Suggest regulatory and management reforms that might prevent a future

debacle of the type that bankrupted Barings.

Due to incidents of staggering losses to corporate and banking entities as early as 1993, calls

for financial reforms, particularly in relation to derivatives, had been ongoing for quite some

time. However, it took the Baring Brothers bankruptcy to finally bring about action. The Bank

of England, SIMEX and the Group of Thirty all created reports on how regulators,

administrators, legislators, international firms and associations could address the issues of

regulating financial activities.

The Bank of England wrote a report describing how the losses occurred, why they went

unnoticed within and outside Barings, and lessons learned. How the losses occurred and why

they went unnoticed has already been explained. The Bank produced five lessons from the

bankruptcy. They are (Bank of England Report):

1) Management teams have a duty to understand fully the businesses they manage

2) Responsibility for each business activity has to be clearly established and communicated;

3) Clear segregation of duties is fundamental to any effective control system;

4) Relevant internal controls, including independent risk management, have to be established for

all business activities;

5) Top management and the Audit Committee have to ensure that significant weaknesses,

identified to them by internal audit or otherwise, are resolved quickly

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-13

8. Suggest regulatory and management reforms that might prevent a

future debacle of the type that bankrupted Barings. (continued)

Despite these simplistic recommendations, at least one and usually several, of the

points was the reason why firms lost large sums of money within the derivatives

market.

SIMEX, like the other exchanges in the world, implemented changes to decrease

default and counterparty risk as well as systemic risks.

These changes were made as a direct result of the Barings collapse. SIMEX joined

with other exchanges to share information about similar positions participants held

on different exchanges.

To reduce the risk of non-payment of contracts, SIMEX and other exchanges

placed the resources of their entire membership behind the settlements.

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-14

8. Suggest regulatory and management reforms that might prevent a

future debacle of the type that bankrupted Barings. (continued)

The Group of Thirty based out of Washington, DC, has become particularly

concerned with the risks derivatives pose. Since 1995, it has issued several

publications to address these problems.

The first of these was published in August 1996, and is titled International

Insolvencies in the Financial Sector, Discussion Draft. This document advances

fourteen ideas to reduce the risk in the financial sector particularly with regard to

derivatives (see Exhibit 2 for the complete list).

The second publication printed in April of 1997 is titled International

Insolvencies in the Financial Sector, Summary of Comments from Respondent

Countries on Discussion Draft. This publication gives the responses and opinions

of those member countries to the proposed reforms.

The support for these reforms was generally very strong among all the countries

that responded. Germany and other countries did mention several drawbacks to

some of the reforms, but they, too, were generally supportive. Ironically,

Singapore expressed reservations or outright opposition to five of the reforms (#1,

2, 4, 6 and 9).1

Nicholas Leeson: Case Questions

Copyright 2009 Pearson Prentice Hall. All rights reserved.

8-15

ING, a Dutch insurance company, was looking to enter the banking business, especially in

Asia. It paid one pound sterling for Baring Brothers and added an additional $1 billion to pay

off the debts Baring Brothers had accumulated and restore the banks capital position. In

addition, ING also had to pay $677 million to the holders of subordinated debt that was

issued by Barings plc, the holding company, just before the bankruptcy.1 Legally, ING was

not liable for the bonds, but since the bondholders were Barings best customers, ING had to

make good on the notes in order to save the customer relationships.

On February 23, 1995, Nick Leeson fled in his Mercedes across the bridge from Singapore to

Malaysia. He hid out in Thailand for the next week with his wife and was caught flying into

Germany one week later. He was extradited back to Singapore, stood trial and was

subsequently sentenced to 6.5 years in a Singapore prison for fraud. In August 1998, Leeson

underwent surgery for colon cancer and began receiving chemotherapy. Despite his

condition, authorities in Singapore did not release Leeson until June 1999.

Christopher Thompson was the Bank of England supervisor in charge of Baring Brothers at

the time of the bankruptcy. He was responsible for allowing Baring Brothers to invest over

the legal limit of 25% of its capital in the SIMEX and OSE. The day before the Bank of

England report was to be published about the Baring Brothers collapse, Thompson resigned.

Nicholas Leeson: Postscript

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Petty Cash Books PDFDocument3 pagesPetty Cash Books PDFJunaid Islam100% (2)

- Insurance Law Review 2013Document496 pagesInsurance Law Review 2013Ekie GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Szolgáltatások: Autóbérlés, Biztosítások/fajtái, Utazási Irodák/bankok, Javítások/garancia, Közüzemi SzolgáltatásokDocument3 pagesSzolgáltatások: Autóbérlés, Biztosítások/fajtái, Utazási Irodák/bankok, Javítások/garancia, Közüzemi SzolgáltatásokHorváth LillaNo ratings yet

- Lecture - 5 - CFI-3-statement-model-completeDocument37 pagesLecture - 5 - CFI-3-statement-model-completeshreyasNo ratings yet

- Systems Design: Job-Order CostingDocument60 pagesSystems Design: Job-Order Costingrachim04No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Practice Test - Problems (Answers)Document12 pagesChapter 1 Practice Test - Problems (Answers)anonymousNo ratings yet

- EFM Three Statement ModelDocument5 pagesEFM Three Statement ModelAmr El-BelihyNo ratings yet

- Harpreet KaurDocument2 pagesHarpreet KaurIT67% (3)

- Relevant Costs For Decision MakingDocument76 pagesRelevant Costs For Decision Makingrachim040% (1)

- Relevant Costs For Decision MakingDocument76 pagesRelevant Costs For Decision Makingrachim040% (1)

- Problem 9-1, 2 & 3Document3 pagesProblem 9-1, 2 & 3Micah April SabularseNo ratings yet

- Mid Test IB1708 SE161403 Nguyễn Trọng BằngDocument14 pagesMid Test IB1708 SE161403 Nguyễn Trọng BằngNguyen Trong Bang (K16HCM)No ratings yet

- Research On Indian Stock ExchangeDocument78 pagesResearch On Indian Stock ExchangesachinNo ratings yet

- PDF Solution Manual Partnership Amp Corporation 2014 2015pdfDocument85 pagesPDF Solution Manual Partnership Amp Corporation 2014 2015pdfGenevieve Anne AlagonNo ratings yet

- Meetings and ResolutionsDocument9 pagesMeetings and ResolutionsAnirudh AroraNo ratings yet

- 164017-212412 20230131 PDFDocument3 pages164017-212412 20230131 PDFAdeela fazlinNo ratings yet

- Effective Life For Rental-Properties-2015Document44 pagesEffective Life For Rental-Properties-2015rachim04No ratings yet

- The Organization & Structure of Banks & Their IndustryDocument19 pagesThe Organization & Structure of Banks & Their Industryrachim04No ratings yet

- 2015-16 Depn Assets Effective Life Table BDocument13 pages2015-16 Depn Assets Effective Life Table Brachim04No ratings yet

- Rental Properties TaxDocument48 pagesRental Properties TaxAnonymous VlQc8csNo ratings yet

- MRP & ErpDocument6 pagesMRP & Erprachim04No ratings yet

- Income Streaming Discretionary TrustsDocument3 pagesIncome Streaming Discretionary Trustsrachim04No ratings yet

- Steps To Supermarket Success NDSS WebinarsDocument28 pagesSteps To Supermarket Success NDSS Webinarsrachim04No ratings yet

- Fasting and Diabetes: Managing Blood Glucose Levels SafelyDocument40 pagesFasting and Diabetes: Managing Blood Glucose Levels Safelyrachim04No ratings yet

- 2020 08 12 Quick Healthy Meal Ideas WebinarDocument40 pages2020 08 12 Quick Healthy Meal Ideas Webinarrachim04No ratings yet

- Framing Business Ethics: CSR and Stakeholder TheoryDocument8 pagesFraming Business Ethics: CSR and Stakeholder Theoryrachim04No ratings yet

- 2020 08 12 Quick Healthy Meal Ideas WebinarDocument40 pages2020 08 12 Quick Healthy Meal Ideas Webinarrachim04No ratings yet

- Inventory ManagementDocument6 pagesInventory Managementrachim04No ratings yet

- 2020 08 14 Exercise Know The Guidelines WebinarDocument27 pages2020 08 14 Exercise Know The Guidelines Webinarrachim04No ratings yet

- Fasting and Diabetes: Managing Blood Glucose Levels SafelyDocument40 pagesFasting and Diabetes: Managing Blood Glucose Levels Safelyrachim04No ratings yet

- Business EthicsDocument9 pagesBusiness Ethicsrachim04No ratings yet

- Financial Statement of BankDocument10 pagesFinancial Statement of Bankrachim04No ratings yet

- Ch3 ForecastsDocument15 pagesCh3 ForecastsRifat NazimNo ratings yet

- Aggregate PlanningDocument5 pagesAggregate Planningrachim04No ratings yet

- Ch3 ForecastsDocument15 pagesCh3 ForecastsRifat NazimNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document32 pagesChapter 6rachim04No ratings yet

- BASICS OF TAXATION in BangladeshDocument12 pagesBASICS OF TAXATION in Bangladeshrachim04No ratings yet

- Ch3 ForecastsDocument15 pagesCh3 ForecastsRifat NazimNo ratings yet

- Ch3 ForecastsDocument15 pagesCh3 ForecastsRifat NazimNo ratings yet

- Ch3 ForecastsDocument15 pagesCh3 ForecastsRifat NazimNo ratings yet

- Managerial Accounting & The Business EnvironmentDocument24 pagesManagerial Accounting & The Business Environmentrachim04No ratings yet

- Laporan Bulanan Mei - Juni 2022Document62 pagesLaporan Bulanan Mei - Juni 2022LailiNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting An Introduction To Concepts Methods and Uses 14th Edition Weil Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesFinancial Accounting An Introduction To Concepts Methods and Uses 14th Edition Weil Solutions Manual 1richardacostaqibnfpmwxd100% (20)

- Bahan Kuis Prak Kompak Senin SiangDocument3 pagesBahan Kuis Prak Kompak Senin SiangAkbaer EkoNo ratings yet

- МСА 2016-2017 частина 2Document644 pagesМСА 2016-2017 частина 2Валентина ЖдановаNo ratings yet

- Module 2 FMODocument14 pagesModule 2 FMOba8477273No ratings yet

- Act 171 5.1-1 Midterm Exam 2021 NoneDocument3 pagesAct 171 5.1-1 Midterm Exam 2021 NoneAngeliePanerioGonzagaNo ratings yet

- BPI Fishermall Savings BetDocument4 pagesBPI Fishermall Savings BetAubrey Ruivivar GumatzNo ratings yet

- Joshua & White Technologies Financial Statement AnalysisDocument2 pagesJoshua & White Technologies Financial Statement Analysisseth litchfield100% (1)

- Example 1: SolutionDocument7 pagesExample 1: SolutionalemayehuNo ratings yet

- Winter Internship Report Presentation at Chittorgarh Central Cooperative Bank LTDDocument13 pagesWinter Internship Report Presentation at Chittorgarh Central Cooperative Bank LTDayushiNo ratings yet

- Valuation of SecuritiesDocument7 pagesValuation of SecuritiesEmmanuelNo ratings yet

- STMKB CorporateProfile - 120123Document22 pagesSTMKB CorporateProfile - 120123SharpbanNo ratings yet

- Bond Valuation & Risk ChapterDocument23 pagesBond Valuation & Risk ChapterSheevun Di GulimanNo ratings yet

- Banoxo SerurReL Ne PrLrPrNAsDocument27 pagesBanoxo SerurReL Ne PrLrPrNAsJohnmill EgranesNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 Engineering Economics Interest Equivalence (Part 2) 1Document23 pagesLecture 5 Engineering Economics Interest Equivalence (Part 2) 1Natanael SiraitNo ratings yet

- TCCI Commercial AppDocument2 pagesTCCI Commercial AppSahba KamalianNo ratings yet

- Best Practices in Financial and Management AccountingDocument2 pagesBest Practices in Financial and Management Accountingsidhartha mohapatraNo ratings yet

- Canara Vehicle Loan - (603) - Four Wheeler: NF-546 NF-965 NF-928 NF-990 NF-967 NF-373Document8 pagesCanara Vehicle Loan - (603) - Four Wheeler: NF-546 NF-965 NF-928 NF-990 NF-967 NF-373Santosh KumarNo ratings yet